Abstract

Background

Liquid biopsy for plasma circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) next-generation sequencing (NGS) is commercially available and increasingly adopted in clinical practice despite a paucity of prospective data to support its use.

Methods

Patients with advanced lung cancers who had no known oncogenic driver or developed resistance to current targeted therapy (n = 210) underwent plasma NGS, targeting 21 genes. A subset of patients had concurrent tissue NGS testing using a 468-gene panel (n = 106). Oncogenic driver detection, test turnaround time (TAT), concordance, and treatment response guided by plasma NGS were measured. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

Somatic mutations were detected in 64.3% (135/210) of patients. ctDNA detection was lower in patients who were on systemic therapy at the time of plasma collection compared with those who were not (30/70, 42.9% vs 105/140, 75.0%; OR = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.1 to 0.5, P < .001). The median TAT of plasma NGS was shorter than tissue NGS (9 vs 20 days; P < .001). Overall concordance, defined as the proportion of patients for whom at least one identical genomic alteration was identified in both tissue and plasma, was 56.6% (60/106, 95% CI = 46.6% to 66.2%). Among patients who tested plasma NGS positive, 89.6% (60/67; 95% CI = 79.7% to 95.7%) were also concordant on tissue NGS and 60.6% (60/99; 95% CI = 50.3% to 70.3%) vice versa. Patients who tested plasma NGS positive for oncogenic drivers had tissue NGS concordance of 96.1% (49/51, 95% CI = 86.5% to 99.5%), and directly led to matched targeted therapy in 21.9% (46/210) with clinical response.

Conclusions

Plasma ctDNA NGS detected a variety of oncogenic drivers with a shorter TAT compared with tissue NGS and matched patients to targeted therapy with clinical response. Positive findings on plasma NGS were highly concordant with tissue NGS and can guide immediate therapy; however, a negative finding in plasma requires further testing. Our findings support the potential incorporation of plasma NGS into practice guidelines.

Analysis of plasma circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) by next-generation sequencing (NGS) is an evolving technology that allows for rapid and noninvasive genotyping of tumors. ctDNA is a subset of cell-free DNA that can be found in plasma and represents genetic material from the primary tumor as well as metastases. ctDNA released by tumor cells undergoing apoptosis, necrosis, and in extracellular vesicles (exosomes) secreted from tumor cells is highly fragmented and ranges between 100 and 200 base pairs in size and is rapidly cleared from the peripheral circulation with a short half-life, ranging from 15 minutes to a few hours (1–3). Plasma ctDNA harboring somatic mutations are highly specific for cancer and may serve as a useful surrogate of tumor burden, intratumor heterogeneity, and response to therapy (4). Plasma-based NGS assays are now commercially available and are increasingly adopted in clinical practice. However, there is a paucity of prospective evidence-based guidance regarding in whom and when to order the test, and its utility in matching patients to targeted therapy. A recent joint review from the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the College of American Pathologists concluded that there was little evidence of clinical validity and clinical utility to support the widespread use of ctDNA in most patients with advanced cancers (5).

Genetic sequencing is particularly important in patients with advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancers as their tumors may harbor somatic alterations that are sensitized to targeted therapies. Genetic sequencing can also detect mutations mediating resistance in patients with known driver alterations after exposure to targeted agents. Plasma-based genotyping may circumvent some of the limitations of standard tissue genotyping such as risks of repeat invasive procedures, insufficient tissue in biopsies, intratumor heterogeneity, and overall slow turnaround time of conventional tissue processing. However, it is unknown whether liquid biopsy could supplement or supplant tissue biopsy in clinical practice.

We hypothesized that plasma ctDNA NGS may be useful in matching patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer to targeted therapy and in predicting their therapeutic benefit. We set out to prospectively study the utility of plasma-based ctDNA NGS in patients with advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer in the real-world clinical practice setting.

Methods

Trial Design

Patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer were prospectively enrolled in an institutional review board (IRB)–approved plasma NGS genotyping protocol. Patients were eligible if they either had no known driver oncogene (“driver unknown”) or had developed acquired resistance to targeted therapy (“resistance unknown”). Patients were then enrolled in a continuous, unblinded, and nonrandom fashion. All patients had radiologic evidence of disease, were aged 18 years or older, and provided written informed consent. Between October 21, 2016 and January 1, 2018, patients underwent peripheral blood sampling at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) (New York, NY), an academic cancer center, and Northern Cancer Institute (Sydney, Australia), a community-based oncology practice affiliated with the University of Sydney. The CONSORT diagram is shown in Supplementary Figure 1 (available online).

Clinical endpoints included test turnaround time (TAT), measured in days from blood sampling until reporting of results to the study investigator; detection rate of ctDNA and oncogenic drivers; concordance or conditional probability of identifying an alteration on plasma and tissue NGS when available; and treatment outcomes of targeted therapy guided by plasma NGS. Patients were subsequently followed and repeat plasma NGS testing was obtained; here we report only the initial plasma NGS testing obtained in each patient.

Plasma NGS Genotyping

Peripheral venous blood was collected in two Streck (Omaha, NE) tubes (10 mL each) and shipped via overnight express mail at room temperature to Resolution Bioscience (ResBio, Redmond, WA). DNA was extracted and targeted plasma NGS was performed using a validated, bias-corrected, hybrid-capture 21-gene assay, ResBio ctDx-Lung, performed in a laboratory certified via the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments with median unique reads at ×3000 and sensitive detection at variant allele frequency above 0.1% (Supplementary Table 1, available online) (6,7). Reports detailing observed point mutations, indels, gene fusions, and copy number alterations (CNAs) were provided to the study investigator as well as the treating clinician in real time in a secure, online repository.

Anchored Multiplex Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) for Targeted ctDNA Sequencing

A subset of patients who had an alteration identified on ResBio plasma ctDNA NGS underwent orthogonal plasma testing with an anchored multiplex PCR assay based on Rapid Amplification of ctDNA Ends (RACE) strategy followed by NGS (Archer Reveal ctDNA 28; ArcherDX, Boulder, CO) to identify cancer-related single-nucleotide variants and indels in 4.8–20 ng of ctDNA isolated from plasma (n = 20). The list of 28 genes in the panel is provided in Supplementary Table 2 (available online). The multiplex RACE products were sequenced on NextSeq (Illumina; San Diego, CA), and sequencing data were analyzed by Archer Analysis software version 5.6 (ArcherDX).

Tissue Genotyping

Next-generation sequencing of tissue biopsies was requested for all MSK patients and was performed using a hybridization capture-based assay: Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT). DNA isolated from tumor tissue and matched normal peripheral blood was subjected to hybridization capture and deep-coverage NGS to detect somatic mutations in 468 cancer-related genes, including small insertions and deletions, CNAs, and chromosomal rearrangements (Supplementary Table 3, available online) (8–10). All mutations were called against the patient’s matched normal sample, and mean overall coverage of sequencing depth ranged from ×500 to 1000. Reports were provided to the treating physician in real time.

Statistical Analysis

To explore the optimal time to detect plasma ctDNA, the mutation detection rate was calculated on and off therapy and compared by χ2 test. Pearson correlation coefficient was used to assess the correlation of variant frequencies between the ResBio assay and Archer NGS assay. Multivariable logistic regression of ctDNA detection rate was performed. Descriptive statistics were used to report ctDNA detection rate, driver detection rate, rate of matched targeted therapy, and response to therapy. The proportion of patients for whom a matched targeted therapy was identified by plasma ctDNA NGS was calculated, along with an exact 95% confidence interval. For patients with both plasma ctDNA NGS and tissue NGS and an identified oncogenic driver alteration, the paired TATs were compared by a Wilcoxon signed-rank test. TAT for plasma-based NGS testing was measured from the time of blood draw to the time of receipt of report by the study investigator and measured in calendar days. TAT of tissue NGS testing was measured from the time of tissue receipt by the molecular pathology laboratory to the time of report in the electronic medical record. In patients who had concurrent tissue NGS results, we assessed the concordance or conditional probability of identifying that alteration in plasma and vice versa. As there is no true gold standard, sensitivity and specificity were not calculated for plasma and tissue NGS testing. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patients

A total of 210 consecutive patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer were enrolled in the study. Patients were enrolled at MSK (n = 176, 83.8%) and Northern Cancer Institute (n = 34, 16.2%). The majority of patients had adenocarcinoma histology (192/210, 91.4%) (Table 1). Patients were predominantly female (124/210, 59.0%). All patients had metastatic disease at the time of plasma NGS genotyping. Most patients (171/210, 81.4%) had prior conventional molecular tumor testing (immunohistochemistry, PCR fluorescence in situ hybridization for EGFR, ALK, and ROS1) performed and resulted on tissue at the time of plasma NGS testing. Thirty-nine patients (18.6%) did not have any conventional molecular testing performed on the tumor because of insufficient tissue. Most patients were categorized as driver unknown (153/210, 72.9%) at the time of plasma NGS genotyping. Fifty-seven patients (27.1%) had known driver alterations and were categorized as resistance mechanism unknown with disease progression at the time of plasma NGS genotyping. Alterations in this cohort of patients included EGFR exon 19 deletion, EGFR exon 21 L858R, EGFR T790M, EGFR exon 20 insertion, MET exon 14 skipping, ERBB2/HER2 insertion, BRAF V600E, KRAS G12D, KRAS G12C, ALK, and ROS1 rearrangements.

Table 1.

Baseline patient and molecular characteristics

| Characteristics | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total | 210 (100.0) |

| MSKCC | 176 (83.8) |

| NCI | 34 (16.2) |

| Median age, (range), y | 65 (28–91) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 124 (59.0) |

| Male | 86 (41.0) |

| Histology | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 192 (91.4) |

| Squamous | 9 (4.2) |

| Pleomorphic/Sarcomatoid | 4 (1.9) |

| Large cell neuroendocrine | 2 (1.0) |

| Poorly differentiated carcinoma | 2 (1.0) |

| Adenosquamous | 1 (0.5) |

| Metastatic disease at blood draw | 210 (100) |

| Conventional molecular results known at time of plasma draw* | |

| Yes | 171 (81.4) |

| No | 39 (18.6) |

| Tissue NGS at time of blood draw | |

| Yes | 28 (13.3) |

| No | 182 (86.7 |

| Driver alteration before blood draw | |

| Unknown | 153 (72.9) |

| Known | 57 (27.1) |

Immunohistochemistry, polymerase chain reaction, and fluorescence in situ hybridization EGFR, ALK, ROS1. MSKCC = Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (New York, NY); NCI = Northern Cancer Institute (St Leonards, Sydney, Australia); NGS = next-generation sequencing.

Plasma ctDNA Detection Rate

The ResBio ctDx-Lung 21-gene targeted NGS assay detected somatic mutations in 64.3% (135/210) of patients (Supplementary Figure 2, available online). Plasma ctDNA detection rate was 42.9% (30/70) if plasma NGS genotyping was performed while the patient was on active systemic therapy and 75.0% (105/140) if plasma NGS genotyping was performed off therapy (OR = 0.26, 95% CI = 0.13 to 0.49, P < .001) (Table 2). Multivariable logistic regression on ctDNA detection rate and clinical factors such as age, sex, smoking, histology, and performance status did not identify any statistically significant variables that predicted the detection of plasma ctDNA (Supplementary Table 4, available online).

Table 2.

Plasma circulating tumor cell DNA (ctDNA) detection rate stratified by systemic therapy (n = 120)

| Systemic treatment | ctDNA detected, no. of samples | ctDNA not detected, no. of samples | Total no. of samples | Detection rate, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| On-treatment | 30 | 40 | 70 | 42.9 |

| Off-treatment | 105 | 35 | 140 | 75.0 |

| Total | 135 | 75 | 210 | 64.3 |

Plasma Driver Alterations

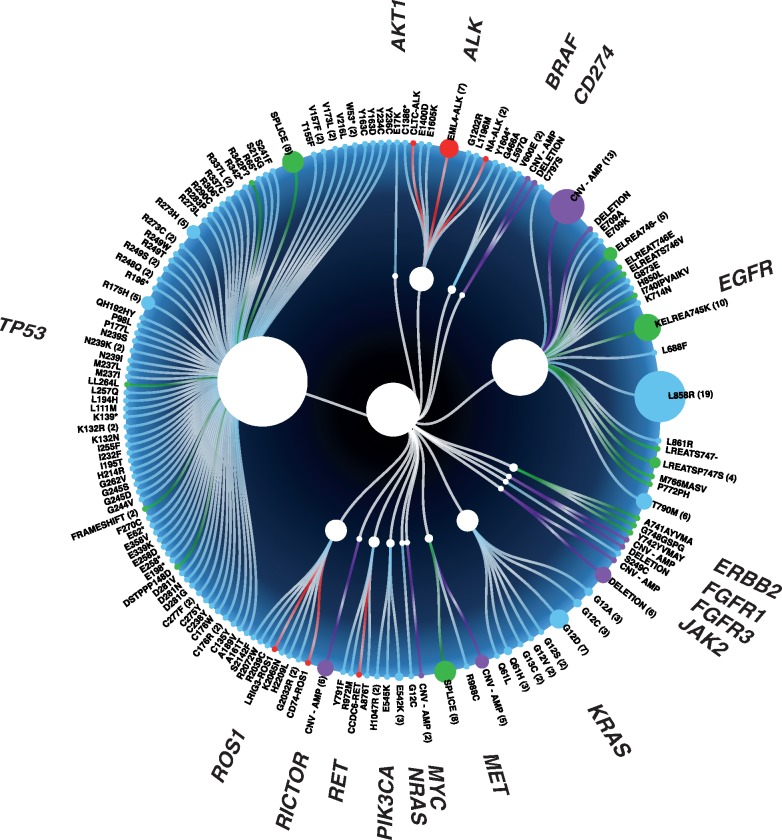

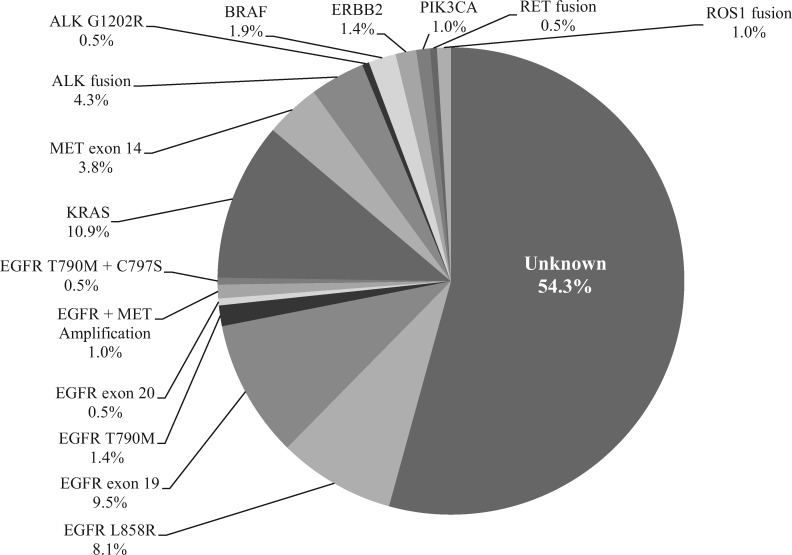

NGS genotyping identified a broad range of tumor-associated alterations (Figure 1) and more importantly identified a driver alteration in 45.7% (96/210) of patients, including actionable alterations such as EGFR mutations, secondary EGFR resistance mechanisms (T790M, C797S, and MET amplification), ALK fusions, MET exon 14 skipping alterations, BRAF alterations, as well as nonactionable alterations such as KRAS and PIK3CA (Figure 2). Plasma NGS genotyping identified actionable driver alterations that led to a patient being matched to targeted therapy in 21.9% (46/210) of patients, including conventional therapies approved by the Food and Drug Administration as well as investigational therapies. Nearly all 35 evaluable patients had a clinical and radiologic response to matched targeted therapy; partial response was achieved in 34 patients and progression of disease in one patient who was identified to have MET amplification and was matched to crizotinib (Table 3). EGFR exon 21 (L858R) was identified in 12 patients, five of whom were treated with erlotinib in the first-line setting, six treated with osimertinib, and one with afatinib. EGFR exon 19 deletion was identified in 11 patients, (one with a concurrent de novo MET amplification), and patients were matched to first-line regimens including erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib, and osimertinib. Secondary resistance mechanisms were detected by plasma NGS genotyping in patients already on targeted therapies: EGFR exon 20 T790M was identified in three patients who were then matched to osimertinib; MET amplification was detected in one patient (who was started on a clinical trial protocol of osimertinib plus MET inhibitor savolitinib). ALK rearrangements were identified in seven patients, three of whom were matched to crizotinib and four were matched to alectinib in the first-line setting. ERBB2 mutation was identified in one patient who enrolled in a clinical trial with ado-trastuzumab emtansine (NCT02675829). BRAF L579Q was identified in one patient who enrolled on a phase I trial protocol of ulixertinib (ERK inhibitor) (NCT01781429) (11). BRAF V600E was identified in two patients who were both matched to dabrafenib and trametinib (12). MET exon 14 skipping alterations were identified in six patients; all were matched to targeted therapy with crizotinib. RET fusion was identified in one patient, who was matched to cabozantinib (13,14).

Figure 1.

Plot of all alterations detected by plasma next-generation sequencing (n = 210). Size of circles represents number of patients identified with an alteration.

Figure 2.

Genetic driver alteration identified by plasma next-generation sequencing (n = 210).

Table 3.

Patients matched to targeted therapy based on plasma next-generation sequencing results and treatment response*

| Patient | Plasma ctDNA alteration | Matched therapy | Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSK-L-007 | EGFR T790M | Osimertinib | Partial response |

| NCI-L-003 | EGFR T790M | Osimertinib | Partial response |

| NCI-L-024 | EGFR T790M | Osimertinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-047 | EGFR exon 19 w/ MET amplification | Erlotinib | Unknown |

| MSK-L-054 | EGFR exon 19 w/ MET amplification | Osimertinib + savolitinib | Protocol |

| NCI-L-040 | EGFR exon 19 | Gefitinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-098 | EGFR exon 19 | Osimertinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-009 | EGFR exon 19 | Erlotinib + bevacizumab | Partial response |

| MSK-L-114 | EGFR exon 19 | Osimertinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-136 | EGFR exon 19 | Osimertinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-143 | EGFR exon 19 | Osimertinib + bevacizumab | Protocol |

| MSK-L-151 | EGFR exon 19 | Osimertinib + bevacizumab | Protocol |

| MSK-L-187 | EGFR exon 19 | Osimertinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-195 | EGFR exon 19 | Osimertinib + bevacizumab | Protocol |

| MSK-L-046 | EGFR L858R | Erlotinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-071 | EGFR L858R | Erlotinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-095 | EGFR L858R | Erlotinib | Partial response |

| NCI-L-38 | EGFR L858R | Erlotinib | Partial response |

| NCI-L-006 | EGFR L858R | Afatinib | Unknown |

| NCI-L-061 | EGFR L858R | Osimertinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-115 | EGFR L858R | Erlotinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-119 | EGFR L858R | Osimertinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-137 | EGFR L858R | Osimertinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-144 | EGFR L858R | Osimertinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-179 | EGFR L858R | Osimertinib | Unknown |

| MSK-L-192 | EGFR L858R | Osimertinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-042 | EML4-ALK | Crizotinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-056 | EML4-ALK | Crizotinib | Partial response |

| NCI-L-034 | EML4-ALK | Crizotinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-063 | EML4-ALK | Alectinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-069 | NA-ALK | Alectinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-086 | EML4-ALK | Alectinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-165 | EML4-ALK | Alectinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-023 | MET exon 14 | Crizotinib | Protocol |

| MSK-L-029 | MET exon 14 | Crizotinib | Protocol |

| MSK-L-052 | MET exon 14 | Crizotinib | Protocol |

| MSK-L-059 | MET exon 14 | Crizotinib | Protocol |

| MSK-L-076 | MET exon 14 | Crizotinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-182 | MET exon 14 | Crizotinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-065 | BRAF V600E | Dabrafenib + trametinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-200 | BRAF V600E | Dabrafenib + trametinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-014 | BRAF L597Q | Ulixertinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-012 | ERBB2 insYVMA | TDM1 | Partial response |

| MSK-L-100 | ROS1 G2032R resistance | Cabozantinib | Partial response |

| MSK-L-185 | MET amplification | Crizotinib | Progression of disease |

| MSK-L-192 | RET rearrangement | Cabozatinib | Partial response |

ctDNA = circulating tumor DNA; MSK = Memorial Sloan Kettering; NCI = Northern Cancer Institute; TDM1 = trastuzumab emtansine.

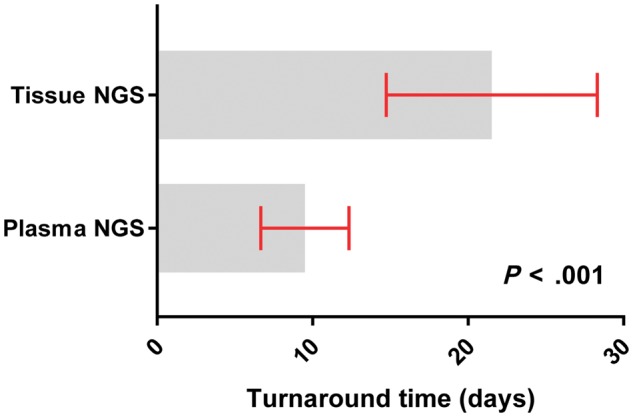

Plasma NGS TAT

Plasma NGS was successfully completed in 210 patients with a median TAT of nine days from the time of blood draw to the time of the primary investigator receipt of report (range = 4–22 days). By comparison, the median TAT for tissue NGS for the 106 patients who had concurrent MSK-IMPACT testing was 20 days (range = 13–69 days), from time of tissue receipt to time of receipt of report. TAT for results from plasma NGS was shorter than tissue NGS (median = 7 vs 20 days, P < .001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Turnaround time of plasma and tissue next-generation sequencing (NGS). Plasma samples, n = 210; tissue samples, n = 107. The paired turnaround times were compared by a two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Tissue and Plasma Concordance

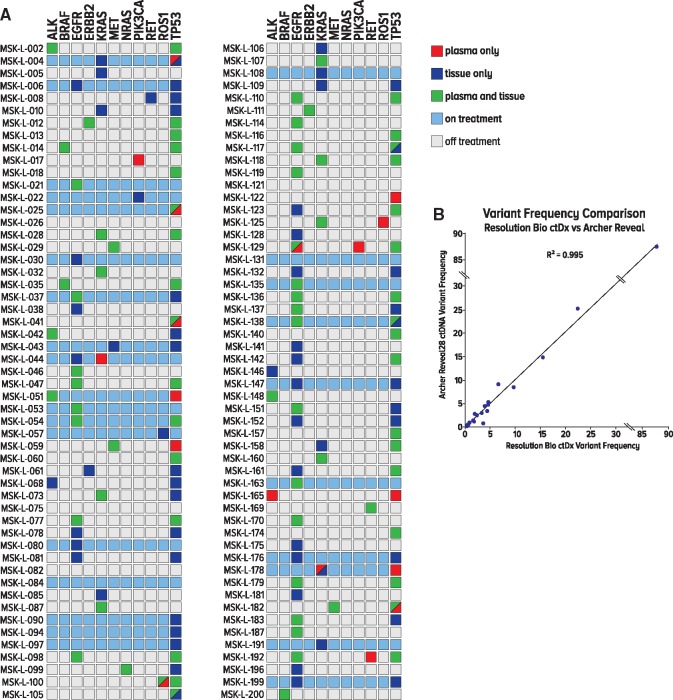

All patients who underwent plasma NGS genotyping at MSK (176/210) were offered concurrent tissue–based NGS to assess tissue and plasma concordance. MSK-IMPACT NGS was offered to all 176 patients at MSK; 60.2% (106/176) had tissue NGS results. Of note, one patient who underwent tissue NGS was not identified to have any mutations. The difference between plasma draw date and actual date of tissue biopsy was a median of 21 days, with an interquartile range of 183 days. The proportion of patients for whom at least one identical genomic alteration was found in both tissue and plasma was 56.6% (60/106; 95% CI = 46.6% to 66.2%) (Figure 4A). Among patients who tested plasma NGS positive, 89.6% (60/67; 95% CI = 79.7% to 95.7%) were concordant on tissue NGS. Among patients who tested tissue NGS positive, 60.6% (60/99; 95% CI = 50.3% to 70.3%) were also concordant on plasma NGS (Supplementary Table 5, available online). Among patients who tested plasma NGS positive for the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, recognized oncogenic driver alterations (EGFR, KRAS, ALK, ROS1, RET, BRAF, MET, HER2) (15), 96.1% (49/51; 95% CI = 86.5% to 99.5%) were concordant on tissue NGS. The two discordant cases included a KRAS G12S mutation found on plasma NGS that was not identified on tissue NGS (MSK-L-044) and a MET amplification found on plasma but not identified on tissue NGS (MSK-L-047).

Figure 4.

Concordance and orthogonal validation of plasma next-generation sequencing. A) Concordance between tissue and plasma next-generation sequencing (NGS). All patients were offered concurrent tissue NGS. A total of 107 patients had tissue NGS results available. One patient did not have any mutations identified on tissue NGS. Green square represents an alteration identified on both plasma and tissue NGS. Red square represents an alteration identified on plasma and not on tissue NGS. Blue square represents an alteration identified on tissue and not on plasma NGS. Light blue identifies patients who were on systemic therapy at the time of plasma blood draw. B) Correlation between Resolution Bioscience and Archer NGS variant frequencies. Scatterplot showing variant frequencies for the same samples analyzed with the Resolution Bioscience NGS platform as a function of the variant frequencies obtained with the Archer NGS platform. Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated. ctDNA = circulating tumor.

Reproducibility of Plasma Findings

Correlation between ResBio plasma NGS assay and Archer NGS variant frequencies were performed on a subset of 18 samples. A scatterplot showing variant frequencies for the same samples analyzed with the ResBio NGS platform as a function of the variant frequencies obtained with the Archer NGS platform shows excellent linearity with Pearson correlation coefficient r = 0.995 (Figure 4B).

Discussion

This is the first prospective clinical study of liquid biopsy for plasma ctDNA NGS analysis in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer with TAT and ctDNA-guided treatment outcomes. We demonstrate that plasma NGS genotyping is feasible, rapid, and useful in the real-world clinical practice setting for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Plasma NGS directly matched patients to targeted therapy often before tissue genotyping results became available, and led to clinical and radiologic response. A driver alteration identified by plasma NGS can immediately direct clinical care. However, a negative result requires further investigation. Based on our findings, plasma NGS genotyping is best performed at initial diagnosis in conjunction with tissue biopsy and at the time of clinical or radiologic progression, as the yield of ctDNA might be highest at those times based on its correlation with tumor burden (16).

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network now recommends routine mutation testing for EGFR, BRAF, ERBB2, and MET; rearrangements in ALK, ROS1, and RET; and MET amplification in all patients diagnosed with metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. An NGS platform offers the patient and the clinician a single test that is able to capture point mutations (single-nucleotide variants), indels, copy number variants, and gene rearrangements across many cancer-related genes. NGS as a whole outperforms each individual molecular test and is therefore a critical tool in the effective diagnosis and treatment of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (17). In this study, we have shown that plasma-based ctDNA NGS assays allow for rapid and noninvasive genotyping that could immediately guide precision therapy, providing an important supplement to tissue NGS, as well as an important alternative when tissue biopsy is not feasible.

One current advantage of plasma NGS compared with tissue NGS shown in this study is the shorter TAT for results. Whole blood can be drawn in Streck tubes, where DNA remains stable for up to 7–14 days, and can be shipped at room temperature across the world (in this study, from Australia to the United States) to laboratories that have optimized sequencing platforms. Moreover, the improved TAT does not take into account the additional time needed to schedule a tissue biopsy and send materials collected to a molecular pathology laboratory (relative to same-day blood collection in a clinic), which in reality adds extra days or weeks to the TAT of tissue-based NGS.

This study did not analyze serial plasma ctDNA or its utility for treatment response monitoring, although this is another potential use of ctDNA in the clinic (1). Prospective studies comparing radiologic response such as RECIST (response evaluation criteria in solid tumors) with molecular response by plasma ctDNA levels are needed to better understand the utility of plasma ctDNA NGS testing, including its temporal relationship to RECIST responses and the “amplitude” of ctDNA response as a surrogate for response to therapy.

Plasma NGS genotyping has some fundamental limitations, including the low concentration of ctDNA shed into the peripheral circulation (4). The inability of plasma NGS to detect drivers in some cases in this study means a negative finding on ctDNA does not exclude the presence of a targetable driver. Technical factors including plasma sequencing depth may influence results, and ultra-deep sequencing methods are currently being developed to further improve plasma detection. Biological factors such as tumor shedding and ctDNA kinetics remain an ongoing area of investigation in the field of liquid biopsy. Plasma NGS genotyping in our study, as in others, has a lower driver detection compared to tissue-based NGS (18). However, the lower detection notwithstanding, plasma NGS may be advantageous in its faster TAT, and the ability to assess the systemic genomic landscape and incorporate tumor heterogeneity, particularly in patients with multiple metastatic sites that may be evolutionarily distinct from the primary site that was biopsied at the time of initial diagnosis. This opportunity may be particularly important in the setting of acquired resistance to targeted therapies with the emergence of subclonal resistance mutations (19).

For successful integration of plasma NGS into clinical practice, universal guidelines, both from an informatics and a technical standpoint, are essential and need to span multiple companies and institutions. Not all assays are the same. Amplicon-based targeted NGS, although potentially more rapid and less expensive, may not be as sensitive as capture-based technologies including for the detection of fusions, where the locations of both gene partners may be required in advance (20,21). NGS panels that monitor selected introns and exons facilitate the detection of specific fusions only if the breakpoint falls within a preselected region. Introns can often be long, and are frequently excluded from panels due to the cost of sequencing (22).

Our study provides prospective evidence to support the incorporation of plasma NGS into lung cancer practice guidelines. More research is required to better understand the kinetics of tumor shedding and the effects of treatment (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy) on plasma levels of ctDNA. Other exciting questions on the future use of plasma-based NGS include detection in earlier stage or minimal residual disease to guide neo-adjuvant or adjuvant therapies and as a screening modality for the early detection of cancers (23).

In patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer, plasma NGS identified a variety of oncogenic drivers with statistically significantly shorter TAT compared with tissue NGS, and matched patients onto targeted therapy with clinical benefit. Plasma ctDNA is most detectable at diagnosis of metastatic disease or at progression. A positive finding of an oncogenic driver in plasma can immediately guide treatment, but a negative finding may still require additional testing. Our findings provide prospective evidence to support the incorporation of plasma NGS into practice guidelines.

Funding

This research was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (T32 CA009207, P30 CA008748) and the Nussbaum/Kuhn Foundation.

Notes

Affiliations of authors: Thoracic Oncology Service, Division of Solid Tumor Oncology, Department of Medicine, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY (JKS, MO, DS, AN, SD, NT, AMar, MLM, AMak, YL, HAY, PKP, JEC, MGK, MDH, AD, GJR, CMR, BTL); Northern Cancer Institute, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia (AL, NP, SC, CID); Diagnostic Molecular Pathology Service, Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY (JOJ, LAB, ML, MEA); Resolution Bioscience, Redmond, WA (JH, SH, TS, KG, DDP, CKR, LPL, ML); Thoracic Service, Department of Surgery (VWR, DRJ, JMI); and Department of Radiation Oncology (AR), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY.

The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

MO, DS, AN, SD, NT, AMar, MLM, AMak, YL, JOJ, LAB, DRJ, and JMI have no disclosures to report. JKS and BTL have received travel support from Resolution Bioscience for an academic conference presentation.

AL received travel support from Sanofi Aventis and honoraria from Eisai. NP is a consultant for Pfizer, Novartis, Amgen, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Merck-Serono, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Merck, and received travel support from Roche and Bristol-Myers Squibb. SC is a consultant for Merck, Ipsen, Bayer, and AstraZeneca and received honoraria from Merck. CID is a consultant for Ipsen, received honoraria from Pfizer and Amgen, and travel support from Roche and Ipsen. HAY is a consultant for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Lilly and has received research support from Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Incyte, and Lilly. PKP received research support from Celgene, AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline. JEC is a consultant for AstraZeneca/Medimmune, Clovis Oncology, and Genetech Roche, has received honoraria from DAVAOncology and research support from AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, and Novartis. MGK is a consultant for AstraZeneca. ML is a consultant for AstraZeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim, and has received honoraria from Merck and research support from Loxo. MEA is a consultant for AstraZeneca and has received travel support from AstraZeneca, Invivoscribe, and Raindance Technologies. MDH is a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Genentech Roche, AstraZeneca/MedImmune, Novartis, and Janssen, and received research support from Bristol-Myers Squibb. AD is a consultant for Ignyta, Loxo, TP Therapeutics, AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Blueprint Medicines, Genentech Roche, and Takeda, and has received research support from Foundation Medicine. GJR is a consultant for Genentech Roche, received travel support from Merck Sharp and Dohme, and research support from Novartis, Genentech Roche, Millennium, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Infinity Pharmaceuticals, and Ariad. VWR is a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, and received research support from Genelux and travel support from da Vinci Surgery. AR is a consultant for Varian Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, and Merck, and received research support from Varian Medical Systems, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and AstraZeneca, and honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb. CMR is a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Abbvie, Seattle Genetics, Harpoon Therapeutics, Genentech Roche, and AstraZeneca. BTL is a consultant for Genentech Roche, Thermo Fisher Scientific, and Guardant Health. JH, SH, TS, KG, DDP, CKR, LPL, and ML are employed by Resolution Bioscience and are current shareholders or hold vested employee stock options.

Part of this study was presented as an oral abstract at the IASLC 18th World Conference on Lung Cancer; Yokahama, Japan, on October 18, 2017.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Diaz LA, Bardelli A.. Liquid biopsies: genotyping circulating tumor DNA. J Clin Oncol. 2014;326:579–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bettegowda C, Sausen M, Leary RJ, et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6224:224ra24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li BT, Drilon A, Johnson ML, et al. A prospective study of total plasma cell-free DNA as a predictive biomarker for response to systemic therapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancers. Ann Oncol. 2016;271:154–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diehl F, Schmidt K, Choti MA, et al. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat Med. 2008;149:985–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Merker JD, Oxnard GR, Compton C, et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology and College of American Pathologists Joint Review. J Clin Oncol. 2018: 3616:1631–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raymond CK, Hernandez J, Karr R, Hill K, Li M.. Collection of cell-free DNA for genomic analysis of solid tumors in a clinical laboratory setting. PLoS One. 2017;124:e0176241.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Paweletz CP, Sacher AG, Raymond CK, et al. Bias-corrected targeted next-generation sequencing for rapid, multiplexed detection of actionable alterations in cell-free DNA from advanced lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;224:915–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cheng DT, Mitchell TN, Zehir A, et al. Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT). J Mol Diagn. 2015;173:251–264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zehir A, Benayed R, Shah RH, et al. Mutational landscape of metastatic cancer revealed from prospective clinical sequencing of 10,000 patients. Nat Med. 2017;236:703–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jordan EJ, Kim HR, Arcila ME, et al. Prospective comprehensive molecular characterization of lung adenocarcinomas for efficient patient matching to approved and emerging therapies. Cancer Discov. 2017;76:596–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sullivan RJ, Infante JR, Janku F, et al. First-in-class ERK1/2 inhibitor ulixertinib (BVD-523) in patients with MAPK mutant advanced solid tumors: results of a phase I dose-escalation and expansion study. Cancer Discov .2018;82:184–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Planchard D, Smit EF, Groen HJM, et al. Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with previously untreated BRAFV600E-mutant metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;1810:1307–1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Drilon A, Rekhtman N, Arcila M, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced RET-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer: an open-label, single-centre, phase 2, single-arm trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;1712:1653–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Drilon A, Wang L, Hasanovic A, et al. Response to cabozantinib in patients with RET fusion-positive lung adenocarcinomas. Cancer Discov. 2013;36:630–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ettinger DS, Wood DE, Aisner DL, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer, version 5.2017, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;154:504–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abbosh C, Birkbak NJ, Wilson GA, et al. Phylogenetic ctDNA analysis depicts early-stage lung cancer evolution. Nature. 2017;5457655:446–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Drilon A, Wang L, Arcila ME, et al. Broad, hybrid capture-based next-generation sequencing identifies actionable genomic alterations in lung adenocarcinomas otherwise negative for such alterations by other genomic testing approaches. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;2116:3631–3639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schwaederle M, Husain H, Fanta PT, et al. Detection rate of actionable mutations in diverse cancers using a biopsy-free (blood) circulating tumor cell DNA assay. Oncotarget. 2016;79:9707–9717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Murtaza M, Dawson SJ, Tsui DW, et al. Non-invasive analysis of acquired resistance to cancer therapy by sequencing of plasma DNA. Nature. 2013;4977447:108–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Newman AM, Bratman SV, To J, et al. An ultrasensitive method for quantitating circulating tumor DNA with broad patient coverage. Nat Med. 2014;205:548–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Newman AM, Lovejoy AF, Klass DM, et al. Integrated digital error suppression for improved detection of circulating tumor DNA. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;345:547–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schram AM, Chang MT, Jonsson P, Drilon A.. Fusions in solid tumours: diagnostic strategies, targeted therapy, and acquired resistance. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;1412:735.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Li BT, Stephens D, Chaft JE, et al. Liquid biopsy for ctDNA to revolutionize the care of patients with early stage lung cancers. Ann Transl Med. 2017;523:479.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.