Abstract

Background

Variability of short-lived urinary pesticide metabolites during pregnancy raises challenges for exposure assessment.

Objectives

For urinary metabolite concentrations 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA) and 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol (TCPy), we assessed: (1) temporal variability; (2) variation of two urine specimens within a trimester; (3) reliability for pesticide concentrations from a single urine specimen to classify participants into exposure tertiles; and (4) seasonal or year variations.

Methods

Pregnant mothers (N = 166) in the MARBLES (Markers of Autism Risk in Babies-Learning Early Signs) Study provided urine specimens (n = 528). First morning void (FMV), pooled, and 24-h specimens were analyzed for 3-PBA and TCPy. For 9 mothers (n = 88 specimens), each urine specimen was analyzed separately (not pooled) to estimate within- and between-person variance components expressed as intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC). Pesticide concentrations from two specimens within a trimester were also assessed using ICC’s. Agreement for exposure classifications was assessed with weighted Cohen’s kappa statistics. Longitudinal mixed effect models were used to assess seasonal or year variations.

Results

Urinary pesticide metabolites were detected in ≥ 93% of specimens analyzed. The highest ICC from repeated individual specimens was from specific gravity-corrected FMV specimens for 3-PBA (ICC = 0.13). Despite high within-person variability, the median concentrations did not differ across trimesters. Concentrations from pooled specimens had substantial agreement predicting exposure categories for TCPy (K = 0.67, 95% CI (0.59, 0.76)) and moderate agreement for 3-PBA (K = 0.59, 95% CI (0.49, 0.69)). TCPy concentrations significantly decreased from 2007 to 2014.

Conclusions

Pooled specimens may improve exposure classification and reduce laboratory costs for compounds with short biological half-lives in epidemiological studies.

Keywords: Pesticides, Pregnancy, Exposure, Variability, Longitudinal

1. Introduction

Pesticides are widely used in the United States (US) to control pests in agricultural and residential settings. In 2001 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) restricted the use of chlorpyrifos, the most common organophosphate pesticide, for residential use due to concerns over harmful effects on human health including risks to children’s development (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2000). Between 2000 and 2012 organophosphate pesticide use in the US has declined by 70% (Atwood and Paisley-Jones, 2017). Meanwhile, the use of pyrethroid compounds grew as they have largely replaced chlorpyrifos to treat pests in and around the home (Bekarian et al., 2006).

The most recent US EPA market report on 2012 data shows chlorpyrifos was the most commonly used insecticide for agriculture purposes with 4–8 million pounds applied in the US, and was 14th considering all pesticide markets (Atwood and Paisley-Jones, 2017). Since the US EPA restriction of chlorpyrifos for residential use, diet has become a more common route for organophosphate pesticide exposures (Lu et al., 2006b). Pyrethroids are commonly used indoors to treat pests in or around the home and for pet flea/tick treatments (Lu et al., 2006b; Trunnelle et al., 2014). Pyrethroids were ranked as the 3rd most commonly used insecticide (7th most commonly used pesticide) for the US home and garden sector with 1–3 million pounds used in 2012 (Atwood and Paisley-Jones, 2017). Exposure to both organophosphates and pyrethroids is widespread in the US and these two classes of pesticides are commonly detected in biospecimens from the general population (Barr et al., 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017) including pregnant women (Berkowitz et al., 2003; Bradman et al., 2003; Woodruff et al., 2011), and children (Lu et al., 2006a, 2006b).

Pesticide exposure among pregnant women is a public health concern because many of the infant organ systems, including the nervous system, undergo rapid growth during the prenatal period (Landrigan et al., 1999). Epidemiology studies have found that prenatal exposure to organophosphate pesticides has been associated with adverse child development including cognition (Engel et al., 2007; Eskenazi et al., 2007; Horton et al., 2012), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) (Marks et al., 2010; Rauh et al., 2006), and Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) (Roberts et al., 2007; Shelton et al., 2014).

Pyrethroids are synthetic derivatives of pyrethrins, naturally occurring compounds in Chrysanthemum cinerariaefolium which degrade readily in sunlight (ASTDR, 2003). Pyrethroids are similar in structure to pyrethrins, but this class of synthetic insecticides is more chemically stable allowing greater persistence in the environment. Pyrethroid pesticides target the nervous system of insects and act on voltage gated sodium channels (Soderlund et al., 2002). Animal studies suggest there is potential for developmental neurotoxicity in humans (Shafer et al., 2005). Findings from recent studies of pyrethroid exposure during pregnancy suggest in utero exposure may impact the developing brain (Shelton et al., 2014; Watkins et al., 2016).

We come into contact with pesticides from exposures in or around our homes and workplaces, and from residues on foods. Many environmental epidemiology studies rely on biomarkers to characterize pesticide exposure because they have the ability to capture all routes of exposure that questionnaires or detailed histories can miss; however, there are limitations for the use of biomarkers to characterize pesticide exposure in epidemiology studies. Urine specimens can be burdensome to collect from study participants and costly to analyze. Pyrethroids and chlorpyrifos are metabolized quickly (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016; Leng et al., 1997) and the use of pesticide concentrations from a single specimen could result in exposure misclassification of study participants.

Pesticide concentrations from a single pregnancy urine specimen are often used in epidemiology studies to assess pesticide exposure. However a single specimen may be a poor measure of long-term exposure due to rapid metabolism of pesticides. Epidemiology studies are limited by laboratory costs for analyzing multiple biospecimens from each participant, but methods for pooling specimens across study participants has been shown to reduce analytical costs and minimize the amount of information lost for specimens below the limit of detection (Schisterman and Vexler, 2008). Therefore it is important to understand how pesticide concentrations can change during pregnancy, and potentially affect characterization of exposure in environmental epidemiology studies.

In the present study we investigated two pesticide biomarkers analyzed from urine specimens collected during pregnancy from participants in the Markers of Autism Risks in Babies - Learning Early Signs (MARBLES) Study at the University of California, Davis. Pyrethroid metabolite 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA) is a biomarker for the summed exposure of several pyrethroids (Baker et al., 2004), and 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol (TCPy) is a metabolite of chlorpyrifos and chlorpyrifos-methyl (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). The aim of this study was to describe variability and ways to efficiently utilize multiple urinary specimens for both pyrethroid metabolite 3-PBA, and chlorpyrifos metabolite TCPy concentrations from first morning void (FMV), 24-h, and pooled urine specimens collected during pregnancy from participants in the MARBLES Study.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

The present study included 166 participants enrolled in the MARBLES Study from 2007 to 2014 with pesticide metabolite concentrations from urine specimens collected during pregnancy. Five mothers had urine specimens from more than one pregnancy therefore only their first pregnancy was included in the present study. The MARBLES Study is an enriched-risk longitudinal cohort in Northern California. The vast majority of women had a previous child with ASD or otherwise had a strong family history; therefore they were at elevated risk (18%) (Ozonoff et al., 2011) for delivering another infant who would develop ASD. Families were recruited from lists of children receiving services for ASD obtained through the California Department of Developmental Services, from other studies at the University of California, Davis Medical Investigation of Neurodevelopmental Disorders (MIND) Institute, and from other referrals and self-referrals. Study participants were enrolled prior to or during pregnancy. Mothers were followed through pregnancy, and infants from birth to 36 months of age. The University of California, Davis (UCD) institutional review board approved the MARBLES Study and informed consent was obtained from each participant.

2.2. Specimen collection and procedures

We defined trimesters using the gestational age calculated from the date of the mothers’ last menstrual period (LMP) and, when available, pregnancy ultrasound information from medical records. The 1st trimester included gestational ages from LMP –13 weeks, the 2nd trimester included gestational ages 14–27 weeks, and the 3rd trimester included gestational ages 28 weeks to birth. The first specimen was analyzed individually and the remaining 2–7 specimens were pooled. For each trimester participants were instructed to collect three FMV specimens, each one week apart, and one 24-h specimen comprised of all urine voids over a 24-h period. We note that some participants delayed initiation of weekly specimen collection, such that the later weeks fell into a subsequent trimester, resulting in more than four FMV specimens in that trimester. FMV specimens were frozen after collection and 24-h specimens were collected the day before a home visit and stored in the participant’s refrigerator until collection the next day. After home visits, the MARBLES Study personnel transported urine specimens to UCD where they were processed and then stored in − 80 °C freezers. The study design included pooled specimens for participants with three or more individual specimens (FMV and/or 24-h) in a trimester. The majority of pooled specimens included a 24-h specimen but some women did not collect a 24-h specimen so 41 pooled specimens are comprised of only FMV specimens. To pool urine specimens 5 mL of each specimen was transferred by pipette into a sterile 20 mL conical tube (or 50 mL conical tube if more than 4 specimens were pooled) and combined using a vortex mixer for 10 s. Next, 2 mL aliquots of the pooled specimen were transferred by pipette into sterile vials. A total of 812 individual specimens were pooled and this resulted in 197 pooled specimens and 243 FMV specimens representing 157 mothers hereafter referred to as the “standard sample”. A subsample of 9 women, with adequate number of specimens from all three trimesters, was selected from participants enrolled early in the MARBLES Study. All individual pregnancy urine specimens (6–12 specimens) were analyzed for pesticide metabolites 3-PBA and TCPy. These 9 mothers provided 88 individual specimens, hereafter referred to as the “subsample”.

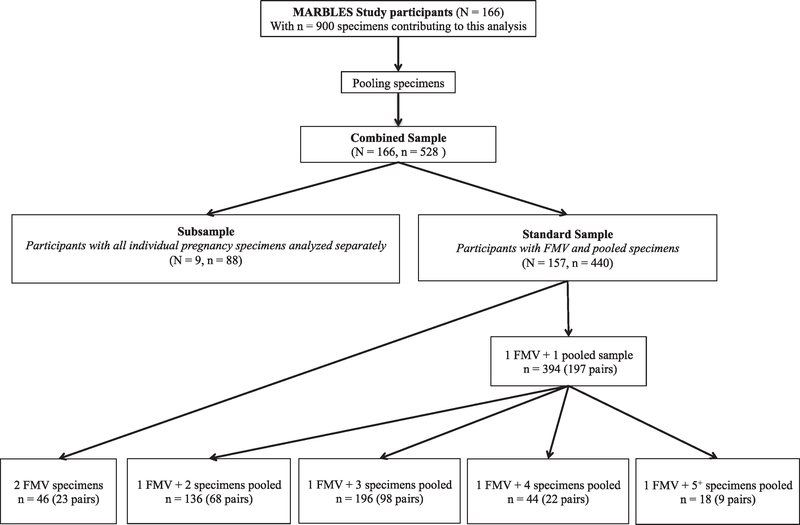

In the present study we included a subsample of participants who each had eight or more individual specimens (N = 9) and participants with at least two urine specimens, either two FMV specimens or a FMV and a pooled specimen, from the 2nd or 3rd trimester (N = 157) (Fig. 1). On average participants completed their first study visit at the beginning of the 2nd trimester (week 18) and we had fewer specimens from the 1st trimester; therefore, our study focuses on FMV and pooled specimens from the 2nd and 3rd trimesters. Some specimens were selected for analysis based on mother’s self-reported trimester. Four specimens were collected within one week of the trimester cutoff date, but the mother had incorrectly reported the gestational age. As the medical record information became available, our choice was to either drop those specimens from our analysis, or leave them in the incorrect trimester. We chose to do the latter.

Fig. 1.

Study design and urine specimen selection for participants from the MARBLES Study contributing urine specimens to this analysis. The total number of participants is indicated with ‘N′ and the total number of urine specimens is indicated by ‘n′. Each urine specimen collected was either a first morning void (FMV) or a 24-h specimen; each pooled sample comprised two or more specimens, including one or more FMV and may also include a 24-h specimen. The total number of urine specimens collected can be calculated by summing the number of specimens in each pooled sample.

2.3. Laboratory methods

Specific gravity (SG) was measured from urine specimens with a handheld refractometer (Atago Urine Specific Gravity Refractometer, PAL 10-S) at UCD. Distilled water was used to calibrate between each measurement. Urine specimens were shipped overnight on dry ice to Emory University’s Rollins School of Public Health for pesticide metabolite analysis. Chemical analyses of 3-PBA and TCPy were conducted according to previously established methods identical to those used in NHANES pesticide assessment (Olsson et al., 2004). Briefly, 2 mL urine specimens were spiked with an internal standard mixture consisting of isotopically labeled 3-PBA and TCPy, and incubated with β-glucuronidase/sulfatase to liberate conjugated metabolites. The hydrolysates were extracted using mixed-mode solid-phase extraction cartridges and elutes were concentrated and analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry with both quantification and confirmation ions monitored (Barr et al., 1999). For quality control, duplicate urine specimens were shipped and analyzed for both pesticide metabolites and specimen blanks were included in runs. The average percent change between 3-PBA and TCPy duplicate specimens was 14% and 3% respectively. Blank specimens were typically indistinguishable from zero. Spiked recoveries ranged from 93% to 106%. The Emory University laboratory participates semi-annually in the G-EQUAS proficiency testing program and is certified in the analysis of 3-PBA and TCPy.

2.4. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, 2016). Characteristics of the study population and descriptive statistics for TCPy and 3-PBA concentrations were calculated. To account for urine dilution, metabolite concentrations were SG corrected using the formula described in Hauser et al. Pc = P × [(SGp-1)/(SG-1)] (Hauser et al., 2004), where Pc is the SG-corrected pesticide metabolite concentration (ng/mL), P is the measured metabolite concentration in ng/mL, SG is the specific gravity of the urine specimen, and SGp (1.012) is the median specific gravity of the MARBLES Study specimens. Concentrations below the limit of detection (LOD) were assigned a value of LOD/ where LOD for both 3-PBA and TCPy was 0.1 ng/mL.

For the subsample of 9 participants we assessed pesticide concentrations and SG across pregnancy with the Kruskal-Wallis Test for nonparametric data with two or more groups. We compared both pesticide concentrations and SG from each trimester of pregnancy. Within- and between-person pesticide metabolite variability over pregnancy was quantified with both Kendall’s rank-transformed intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and the ICC for natural log-transformed pesticide concentrations. For the Kendall’s ICC pesticide concentration values were ranked-transformed and ICCs were computed as the ratio of the estimated between-person variance to the sum of the estimated between- and within-person variance (Carrasco and Jover, 2003; Kraemer, 2006). Mixed effects models with a random effect for subject were used to calculate within- and between-person variance estimates.

In the standard sample (N = 157), variability between FMV and pooled urine specimens within a trimester was assessed with natural log-transformed intraclass correlation coefficients. For each participant exactly two specimens were analyzed per trimester (2nd, 3rd, or both): two FMV specimens or a FMV and a pooled specimen. ICCs were computed within a trimester. To further assess variability, we assigned each participant to a stratum based on the number of individual specimens in the pooled urine specimen.

We calculated the weighted Cohen’s kappa statistic to assess reliability of a single urine specimen to predict the “true” pesticide exposure category. Kappa values can range from 0 to 1 with 0 indicating poor agreement and 1 indicating perfect agreement. Landis and Koch provide guidelines for interpreting kappa values with values from 0 to 0.20 indicating slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 indicating fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 indicating moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 indicating substantial agreement, and 0.81–1 indicating almost perfect agreement (Landis and Koch, 1977). Separate analyses were conducted for the MARBLES Study subsample with individual specimens and the standard sample with FMV and pooled specimens. For each pesticide metabolite, concentrations from single specimens were averaged over pregnancy for each participant. For participants with pooled specimens the number of component specimens was taken into account when averaging pesticide concentrations. This average concentration was used to assign each participant to a “true” exposure category of low, medium, or high exposure, defined by tertile cutoff values at the 33 and 66 percentiles respectively. Next, each urine specimen was assigned to an exposure category which represented the “observed” exposure category a mother would have been assigned to had we only known the pesticide metabolite concentrations from a single specimen.

Next, we combined participants from the standard sample and the subsample to assess whether pesticide concentrations varied by season or specimen collection date. In the combined sample of 166 mothers we fit separate longitudinal mixed models to test associations between both season and sample collection date, and pesticide metabolite concentrations. Due to skewed distributions, pesticide metabolite concentrations were natural log-transformed and longitudinal models were fit with a random intercept term. Pesticide metabolite concentrations served as the dependent variable in each model and season or sample collection date served as the independent variable. Longitudinal models assessing seasonal trends were adjusted for sample collection date. Season of specimen collection was defined as, cold (November – March), warm (April-July), and hot (August-October). We treated specimen collection date as a continuous variable, which ranged from 2007 to 2014.

3. Results

Participants in the subsample were similar to the standard sample on education, race/ethnicity, age, marital status, and home ownership. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of participants were Non-Hispanic white (58%), homeowners (65%), married (91%) and college educated (55%) with mean age 34 years. Both 3-PBA and TCPy were commonly detected in urine specimens from pregnant women in the MARBLES Study with 97% and 94% of specimens above the LOD, respectively. Median and selected percentiles for uncorrected and SG-corrected 3-PBA and TCPy concentrations are presented in Table S1 for the subsample participants (N = 9), and Table 2 for the standard sample (N = 157). Out of the 9 participants in the subsample, four participants had urine specimens from all three trimesters and five participants had specimens from the 2nd and 3rd trimesters. Pesticide concentrations were very similar between the standard sample (Table 2) and the subsample (Table S1). Median concentrations of TCPy and 3-PBA in our population were higher than those reported in NHANES for overlapping years from 2007 to 2010 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017).

Table 1.

Characteristics of mothers from the MARBLES Study with pesticide metabolite concentrations from urine specimens collected during pregnancy, 2007–2014.

| Participant Characteristics | Subsample (N=9) | Standard sample (N=157) |

|---|---|---|

| % (N) | % (N) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 44.4 (4) | 58.7 (88) |

| Hispanic | 44.4 (4) | 17.3 (26) |

| Black | 0 | 5.3 (8) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 11.1(1) | 15.3 (23) |

| Multiracial | 0 | 3.3 (5) |

| Home owner | ||

| Yes | 77.7 (7) | 65.1 (95) |

| No | 22.2 (2) | 34.9 (51) |

| Education | ||

| High school diploma/GED or less | 0 | 7.3(11) |

| Some college | 66.7 (6) | 37.3 (56) |

| Bachelor degree | 22.2 (2) | 39.3 (59) |

| Graduate or professional degree | 11.1(1) | 16.0 (24) |

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 0 | 4.6(7) |

| Married or living together | 100 (9) | 91.4(139) |

| Separated or divorced | 0 | 3.9(6) |

| Smoking history (ever smoked regularly) | ||

| Yes | 44.44 (4) | 19.7 (30) |

| No | 55.56 (5) | 80.3 (122) |

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Age | 36.5 (3.9) | 34.2 (4.9) |

| Urine Specimen Characteristics | n=88 | n = 440 |

| % (n) | %(n) | |

| Trimester of pregnancy | ||

| 1st | 17.1 (15) | N/A |

| 2nd | 48.9 (43) | 41.8(184) |

| 3rd | 34.1 (30) | 58.2 (256) |

| Year of specimen collection | ||

| 2007 | 0 | 10.5 (46) |

| 2008 | 18.2(16) | 16.6 (73) |

| 2009 | 34.1 (30) | 22.9 (101) |

| 2010 | 44.3 (39) | 12.1 (53) |

| 2011 | 3.4(3) | 10.2(45) |

| 2012 | 0 | 11.8 (52) |

| 2013 | 0 | 15.0 (66) |

| 2014 | 0 | 0.91 (4) |

Table 2.

Distribution of urinary pesticide metabolite concentrations (ng/mL) collected during pregnancy from participants in the MARBLES Study, 2007–2014 (N = 157) and participants from NHANES.

| Specimen type | Pesticide metabolites | % < LOD | GM | 95% CI |

Selected percentiles |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 95th | ||||||

| FMV specimens (n = 243) | TCPy | 7.00 | 2.12 | (1.80, 2.51) | < LOD | 1.32 | 2.58 | 4.14 | 14.18 | |

| TCPy SG-corrected | 2.12 | (1.77, 2.54) | 0.12 | 1.09 | 2.44 | 4.49 | 20.71 | |||

| 3-PBA | 2.47 | 1.50 | (1.32, 1.71) | 0.28 | 0.85 | 1.47 | 2.59 | 9.91 | ||

| 3-PBA SG-corrected | 1.50 | (1.29, 1.75) | 0.27 | 0.74 | 1.37 | 2.65 | 12.60 | |||

| SG | 1.014 | (1.013, 1.014) | 1.004 | 1.009 | 1.013 | 1.019 | 1.026 | |||

| Pooled specimens (n = 197) | TCPy | 3.55 | 2.41 | (2.04, 2.84) | 0.42 | 1.42 | 2.67 | 4.46 | 20.41 | |

| TCPy SG-corrected | 2.47 | (2.07, 2.96) | 0.42 | 1.22 | 2.53 | 5.09 | 19.97 | |||

| 3-PBA | 3.55 | 1.70 | (1.45, 2.01) | 0.28 | 0.95 | 1.55 | 3.20 | 9.63 | ||

| 3-PBA SG-corrected | 1.75 | (1.48, 2.08) | 0.24 | 0.93 | 1.62 | 3.20 | 12.16 | |||

| SG | 1.013 | (1.012, 1.013) | 1.006 | 1.009 | 1.012 | 1.016 | 1.022 | |||

| All specimens (n = 440) | TCPy | 5.23 | 2.25 | (2.00, 2.53) | < LOD | 1.34 | 2.62 | 4.30 | 16.13 | |

| TCPy SG-corrected | 2.27 | (2.00, 2.58) | 0.17 | 1.16 | 2.48 | 4.70 | 20.28 | |||

| 3-PBA | 2.95 | 1.59 | (1.44, 1.76) | 0.28 | 0.90 | 1.50 | 2.75 | 9.77 | ||

| 3-PBA SG-corrected | 1.61 | (1.44, 1.80) | 0.26 | 0.85 | 1.47 | 2.85 | 12.17 | |||

| SG | 1.013 | (1.013, 1.014) | 1.005 | 1.009 | 1.013 | 1.017 | 1.024 | |||

| NHANES | n (specimen) | |||||||||

| Adult women (2009–2010)a | ||||||||||

| TCPy | 1404 | 0.70 | (0.63, 0.79) | NR | NR | 0.94 | 1.88 | 4.40 | ||

| 3-PBA | 1392 | 0.42 | (0.37, 0.47) | NR | NR | 0.40 | 1.06 | 6.50 | ||

| Pregnant women (1999 — 2002) | ||||||||||

| TCPyb | 177 | 1.41 | (1.23, 1.61) | NR | 0.61 | 1.60 | 3.05 | 6.85 | ||

| 3-PBAc | 205 | 31.7 | 0.24 | NR | NR | < LOD | 0.23 | 0.46 | 2.19 | |

FMV = first morning void, GM = geometric mean, CI = Confidence Interval, < LOD = below limit of detection, SG = specific gravity, NR = not reported, 3-PBA = 3-phenoxybenzoic acid, TCPy = 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol.

NHANES Fourth Report.

In the subsample, results from the Kruskal-Wallis Test showed concentrations for pesticide metabolites and SG did not significantly differ across trimesters (Table S2). The ICC estimates for pesticide concentrations from individual specimens in the MARBLES subsample are reported in Table 3 with ICCs for all specimen types. The ICC estimates based on natural log-transformed pesticide concentrations and the Kendall’s ranked transformation were similarly low for each pesticide metabolite. The highest reliability estimates, though still low, was for SG-corrected TCPy from all specimens (ICCKendall’s = 0.04, ICCln-transformed = 0.06), and FMV specimens of SG-corrected 3-PBA (ICCKendall’s = 0.13, ICCln-transformed = 0.08).

Table 3.

Intraclass correlation coefficients for pesticide metabolite concentrations (ng/mL) from repeated urine specimens for the same woman collected during pregnancy. MARBLES Study subsample 2007–2014 (N=9).

| Pesticide metabolites | n (specimen) | Kendall’s ICCa | ICCb |

|---|---|---|---|

| FMV specimens | 67 | ||

| TCPy | 0 | 0 | |

| TCPy - SG | 0.01 | 0.02 | |

| 3-PBA | 0.03 | 0.01 | |

| 3-PBA - SG | 0.13 | 0.08 | |

| 24 h specimens | 20 | ||

| TCPy | 0.02 | 0 | |

| TCPy - SG | 0 | 0 | |

| 3-PBA | 0 | 0 | |

| 3-PBA - SG | 0 | 0 | |

| All specimens | 88 | ||

| TCPy | 0 | 0 | |

| TCPy - SG | 0.04 | 0.06 | |

| 3-PBA | 0 | 0 | |

| 3-PBA - SG | 0 | 0 |

Intraclass correlation coefficient using Kendall’s ranked transformation.

Intraclass correlation coefficient using natural log transformed pesticide concentrations, FMV = first morning void, SG = specific gravity corrected, 3-PBA = 3-phenoxybenzoic acid, TCPy = 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol.

Pesticide concentrations from paired FMV and pooled specimens showed similarly low ICCs, overall or when grouped by the number of individual specimens pooled, with all values less than 0.18 (Table 4). We observed higher ICC for FMV and pooled specimens comprised of 5 or more individual specimens but this group only included 9 pairs and this may be a chance finding.

Table 4.

Intraclass correlation coefficient for natural log-transformed pesticide metabolite concentrations (ng/mL) from urine specimens collected during pregnancy from MARBLES Study participants 2007–2014 (N = 157).

| Pesticide metabolite | Paired FMV specimens from the same trimester 2 FMV specimens | Paired spot and pooled specimens from the same trimester |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All spot/pooled specimen pairs | Pooled specimen with 2 components | Pooled specimen with 3 components | Pooled specimen with 4 components | Pooled specimen with 5 + components | ||

| n = 23 | n = 197 | n = 68 | n = 98 | n = 22 | n = 9 | |

| 3-PBA | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.32 |

| 3-PBA -SG | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.50 |

| TCPy | 0.14 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.28 |

| TCPy- SG | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.66 |

ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient using natural log transformed pesticide concentrations, FMV = first morning void, SG = specific gravity corrected, n = number of specimen pairs, 3-PBA = 3-phenoxybenzoic acid, TCPy = 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol.

Reliability analyses for the ability of a single specimen to predict the exposure category a participant would be assigned, based on her average pesticide metabolite concentration from all measurements over pregnancy, are reported in Table 5 with contingency tables and values for weighted Cohen’s kappa statistics (K). In the subsample of 9 participants with individual specimens, we found pesticide concentrations from a single specimen showed fair agreement for both 3-PBA (K = 0.24, 95% CI (0.04, 0.44)) and TCPy (K = 0.27, 95% CI (0.07, 0.47)). For participants in the standard sample, pooled specimens showed substantial agreement for TCPy (K = 0.67, 95% CI (0.59, 0.76)) and moderate agreement for 3-PBA (K = 0.59, 95% CI (0.49, 0.69)). FMV specimens showed fair agreement for 3-PBA (K = 0.36, 95% CI (0.25, 0.47)) and moderate agreement for TCPy (K = 0.43, 95% CI (0.33, 0.54)).

Table 5.

Reliability analysis for specific gravity-corrected urine specimens from MARBLES Study participants 2007–2014.

| Truea (average) | Kappab (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3- PBA | Observedc | Low | Medium | High | |

| Subsample (N = 9) | |||||

| All specimensd | Low | 15 | 6 | 8 | 0.24 (0.04, 0.44) |

| Medium | 9 | 8 | 13 | ||

| High | 5 | 11 | 13 | ||

| Standard sample (N = 157) | |||||

| All specimense | Low | 85 | 34 | 27 | 0.47 (0.39, 0.54) |

| Medium | 54 | 59 | 34 | ||

| High | 7 | 55 | 85 | ||

| FMV | Low | 45 | 26 | 19 | 0.36 (0.25, 0.47) |

| Medium | 29 | 28 | 21 | ||

| High | 6 | 30 | 39 | ||

| Pooled specimens | Low | 40 | 8 | 8 | 0.59 (0.49, 0.69) |

| Medium | 25 | 31 | 13 | ||

| High | 1 | 25 | 46 | ||

| TCPy | |||||

| Subsample (N = 9) | |||||

| All specimensd | Low | 13 | 10 | 6 | 0.27 (0.07, 0.47) |

| Medium | 11 | 10 | 9 | ||

| High | 6 | 8 | 15 | ||

| Standard sample (N = 157) | |||||

| All specimense | Low | 86 | 37 | 23 | 0.54 (0.47, 0.61) |

| Medium | 49 | 63 | 34 | ||

| High | 5 | 42 | 101 | ||

| FMV | Low | 40 | 26 | 17 | 0.43 (0.33, 0.54) |

| Medium | 28 | 30 | 20 | ||

| High | 5 | 25 | 52 | ||

| Pooled specimens | Low | 46 | 11 | 6 | 0.67 (0.59, 0.76) |

| Medium | 21 | 33 | 14 | ||

| High | 0 | 17 | 49 | ||

tertile classification based on average pesticide metabolite concentrations from urine specimens collected during pregnancy.

weighted Cohen’s kappa statistic.

tertile classification based on pesticide metabolite concentrations from a single urine specimen collected during pregnancy.

FMV and 24-h urine specimens.

FMV and pooled urine specimens, FMV = first morning void, CI = confidence interval, 3-PBA = 3-phenoxybenzoic acid, TCPy = 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol.

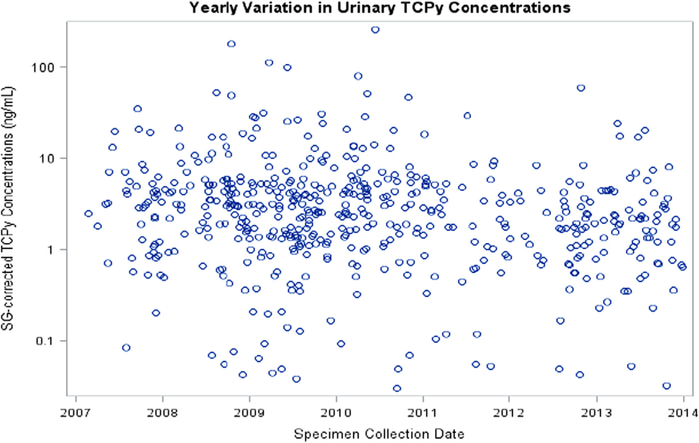

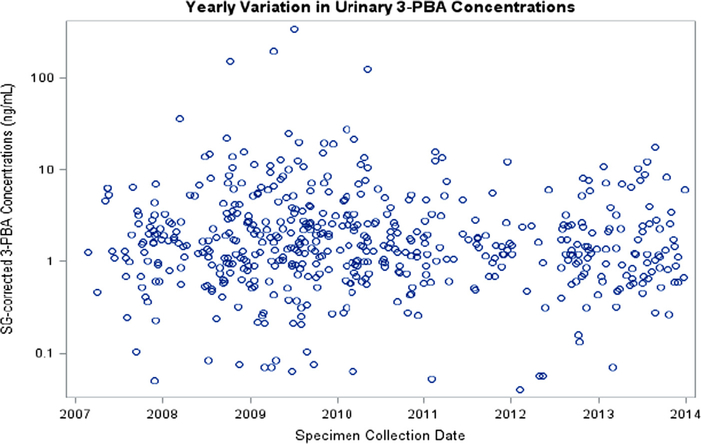

We investigated associations between pesticide concentrations, and both year and season of specimen collection in the combined sample of 166 participants. Thirty-three percent of specimens were collected during cold months, 26% during warm months and 40% during hot months. Season of specimen collection was not significantly associated with SG-corrected concentrations of 3-PBA or TCPy (Table S3). We found an 11% annual decrease in TCPy concentrations (Fig. 2, Table S3); whereas, 3-PBA concentrations were not significantly associated with year of specimen collection (Fig. 3, Table S3).

Fig. 2.

Specific gravity corrected urinary 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol (TCPy) concentrations, from all urine specimens, in relation to specimen collection date from participants in the MARBLES Study (N = 166).

Fig. 3.

Specific gravity corrected urinary 3-Phenoxybenzoic acid (3-PBA) concentrations, from all urine specimens, in relation to specimen collection date from participants in the MARBLES Study (N = 166).

4. Discussion

Few studies have characterized patterns of pyrethroid and chlorpyrifos exposure during pregnancy. In the present study we collected multiple urine specimens from pregnant women across each trimester, which gave us the ability to investigate pesticide metabolite concentrations by specimen type and correction method. Pesticide concentrations from urine specimens collected from 166 pregnant women in Northern California confirm widespread exposure to both pyrethroids and chlorpyrifos with 93% of specimens above the LOD in this non-occupationally exposed population. This may be the first study to investigate both 3-PBA and TCPy concentrations with multiple urine specimens from each trimester, collected from pregnant women in the US.

Median 3-PBA concentrations from urine specimens collected during pregnancy in the standard sample and a subsample of 9 women were 1.50ng/mL and 1.20ng/mL respectively. These concentrations are higher than median concentrations reported in a population-based sample of women in the 2009–2010 NHANES (0.40 ng/mL) and more similar, but still higher than, the 75th percentile (1.06 ng/mL). Levels higher than NHANES have been reported for a sample of 90 adults ages 18–57 sampled in 2009 from northern California with median urinary 3-PBA concentration of 0.82 ng/mL and 75th percentile concentrations of 1.58 ng/mL (Trunnelle et al., 2014). This population is geographically similar to the MARBLES Study population but 2009 was the only sampling year that overlapped with the present study. The higher concentrations detected in MARBLES specimens may reflect growing use of pyrethroids since the 2001 EPA restriction of chlorpyrifos (Bekarian et al., 2006). Concentrations of 3-PBA have been increasing in the NHANES population with median concentrations almost doubling from 1999 to 2000 (0.25 ng/mL) to 2009–2010 (0.40 ng/mL).

Participants in the present study were sampled from 2007 to 2014 and we report higher TCPy median concentrations (standard sample 2.62 ng/mL, subsample 2.13 ng/mL) than adults from NHANES for overlapping years 2009–2010 (0.94 ng/mL) and pregnant women in the 1999–2002 NHANES (1.60 ng/mL) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017). Nationally, chlorpyrifos use has been declining (Atwood and Paisley-Jones, 2017), and the higher levels detected in the MARBLES Study may reflect geographical differences in chlorpyrifos use and exposure. The findings in our study are similar to median TCPy concentrations reported from two pregnancy specimens, collected earlier than the present study, from mothers living in Salinas Valley, California (medians ranged from 2.1 to 3.2 ng/mL) sampled from 1999 to 2001 (Castorina et al., 2010), and the 75th percentile (2.57 ng/mL) reported from adults sampled in 2009 from a geographically similar region of northern California (Trunnelle et al., 2014) supporting this explanation.

We examined within- and between-person variance components ranked-transformed and natural log-transformed for 9 participants with 88 individual specimens. The ICC is commonly used as a measure of reliability to evaluate biomarkers as an indicator of consistency of exposure. The ICC estimates from both 3-PBA and TCPy concentrations were low, due to much more within- than between-person variation. These estimates were based on a small sample size. Nevertheless, low ICCs indicate that epidemiology studies would need several urine specimens to characterize pesticide exposures during pregnancy. Overall we did not observe changes in mean pesticide concentrations across pregnancy trimesters (Table S2) but the ICC estimates indicated considerable within-person variability. The ICCs for 3-PBA concentrations ranged from 0 to 0.13 and such very low ICC results from our study population are similar to those reported from a population of adults in North Carolina. Morgan et al. reported low ICCs for 3-PBA concentrations from different specimen types (first morning void, 24-h, bedtime) over different time periods (one day, one week, six weeks), and method (uncorrected, SG-corrected) with ICCs ranging 0.00–0.06 for uncorrected and 0.00–0.11 for SG-corrected 3-PBA concentrations (Morgan et al., 2016).

In the present study, ICC estimates for TCPy ranged from 0 to 0.06 which were lower than have previously been reported. Studies with specimens from earlier years may have reported higher ICCs because chlorpyrifos was widely used in residential products and a greater portion of exposures were coming from residential settings that would vary less than exposures from dietary sources. The ICC results for TCPy concentrations in the MARBLES Study population are lower than those reported by Meeker et al. from adult male participants ages 20–52 with an ICC = 0.18 for SG-corrected TCPy concentrations for 10 specimens collected over a 3 month period (Meeker et al., 2005). Higher ICCs for TCPy concentrations have been reported for a cohort study of pregnant women from Mexico City, Mexico, in which single specimens collected in each trimester of pregnancy showed greater reliability with ICC = 0.41 uncorrected, ICC = 0.29 SG-corrected TCPy (Fortenberry et al., 2014). Little is known about non-occupational exposure to chlorpyrifos in Mexico but Fortenberry et al. comment that chlorpyrifos is licensed for all purpose use in Mexico which includes residential uses (Fortenberry et al., 2014). Dietary exposures contribute considerably to chlorpyrifos exposure in the US whereas residential pesticide use may play a greater role in Mexico City, which would lead to less variability as reflected in the higher ICC estimates. Regulatory actions may change exposure sources and should be considered when using biomarkers to assess pesticide exposure in adults.

Pesticide concentrations from pooled specimens showed substantial agreement for TCPy and moderate agreement for 3-PBA to classify each woman into her “true” exposure category based on her pregnancy average concentration. We found fair agreement for 3-PBA and moderate agreement for TCPy to classify participants into their “true” exposure tertile based on a single specimen from pregnancy. The better agreement observed for pooled specimens (Table 5) could in part be due to pooled specimens contributing a greater fraction of the pregnancy average. When comparing the number of individual specimens in a pooled specimen for participants in concordant cells (perfect agreement) the majority of pooled specimens were comprised of 3 individual specimens. Quite clearly, misclassification can occur in epidemiology studies using a single urine specimen to assign participants to an exposure category of short-lived compounds; however, agreement improved from fair to moderate and substantial with the use of pooled specimens. Based on the evaluation of all urine specimens in the present study we found that pesticide concentrations from pooled specimens may reduce exposure misclassification. Our findings are consistent with a simulation study that found within-subject pooling reduced bias for short half-life compounds like pesticides (Perrier et al., 2016) and pooling multiple specimens can reduce laboratory costs. Given that urine is the preferred matrix for analyzing semivolatile compounds (such as phthalates and phenols), these results will inform epidemiology studies investigating other semivolatile compounds (Calafat et al., 2015).

Pesticide concentrations from two paired specimens within a trimester showed greater within- than between-person variation. We observed higher ICCs (ranging from 0.28 to 0.66) for paired FMV and pooled specimens comprised of 5 or more individual specimens, which may be a chance finding due to only 9 participants with this combination of specimen types from the same trimester. Reliability results indicate pesticide concentrations from FMV and pooled specimens differ. While overall median concentrations were similar, a pooled specimen has the ability to capture average exposures that a FMV specimen may fail to capture.

Pesticide concentrations were not significantly associated with season of specimen collection. Diet has been shown to contribute considerably to organophosphate exposure (Lu et al., 2006b; Morgan et al., 2014) and lack of a significant association with TCPy in our study may reflect less seasonal variability from dietary exposures over the pregnancy period in this California population, where fresh fruits and vegetables are available year-round. We did not confirm findings from other studies showing that pyrethroid concentrations increase in warmer seasons (Attfield et al., 2014; Berkowitz et al., 2003). Higher concentrations of pyrethroids in specimens collected during warmer months might reflect greater use of pesticides in and around the home during these months; however, seasonal differences could be difficult to detect in the MARBLES Study because of the temperate climate in northern California. In the present study TCPy concentrations significantly decreased from 2007 to 2014, which confirms the deceasing trend observed for TCPy concentrations in NHANES. We did not find a significant time trend for 3-PBA concentrations over the sampling period.

A limitation of the present study is that we lacked detailed information to investigate sources of pesticide exposure in this population. The present study was limited to English speakers and may have failed to sample agricultural workers with the highest pesticide exposure levels. Lastly, pyrethroid metabolite 3-PBA and chlorpyrifos metabolite TCPy are commonly used as biomarkers of exposure; however, these metabolites are not specific to the parent compound and may reflect 3-PBA or TCPy in the environment (Barr et al., 1999; Trunnelle et al., 2014).

5. Conclusions

Pyrethroid and chlorpyrifos metabolites were commonly detected in pregnancy urine specimens from participants in the MARBLES Study. Results from reliability analyses showed that multiple individual urine specimens collected within a trimester reduced exposure misclassification and pooling specimens reduced analytical costs. Epidemiology studies often rely on pesticide concentrations from a single urine specimen collected during pregnancy; however, chlorpyrifos and pyrethroid pesticides are non-persistent and rapidly metabolized (less than 24 h). Pooling individual specimens can improve exposure characterization in epidemiology studies and reduce laboratory

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the MARBLES Study participants for making this research possible. The project described was supported by NIEHS grants R01ES020392, R24ES028533, P30ES023513, and P01ES11269, U.S EPA STAR grant 83543201, NICHD grant U54HD079125, Autism Science Foundation Pre-doctoral Training Fellowship, and the UC Davis MIND Institute.

The University of California, Davis institutional review board approved the MARBLES Study and informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest

None.

Appendix A. Supporting information

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.05.002.

References

- ASTDR, 2003. Toxicological Profile For Pyrethrins And Pyrethroids. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attfield KR, Hughes MD, Spengler JD, Lu C, 2014. Within- and between-child variation in repeated urinary pesticide metabolite measurements over a 1-year period. Environ. Health Perspect. 122, 201–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood D, Paisley-Jones C, 2017. Pesticides Industry Sales and Usage 2008–2012. US Environmental Protection Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Baker SE, Olsson AO, Barr DB, 2004. Isotope dilution high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for quantifying urinary metabolites of synthetic pyrethroid insecticides. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol 46, 281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr DB, Barr JR, Driskell WJ, Hill RH Jr., Ashley DL, Needham LL, et al. , 1999. Strategies for biological monitoring of exposure for contemporary-use pesticides. Toxicol. Ind. Health 15, 168–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr DB, Olsson AO, Wong LY, Udunka S, Baker SE, Whitehead RD, et al. , 2010. Urinary concentrations of metabolites of pyrethroid insecticides in the general U.S. Population: national health and nutrition examination survey 1999–2002. Environ. Health Perspect 118, 742–748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekarian N, Payne-Sturges D, Edmondson S, Chism B, Woodruff TJ, 2006. Use of point-of-sale data to track usage patterns of residential pesticides: methodology development. Environ. Health 5, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz GS, Obel J, Deych E, Lapinski R, Godbold J, Liu Z, et al. , 2003. Exposure to indoor pesticides during pregnancy in a multiethnic, urban cohort. Environ. Health Perspect 111, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradman A, Barr DB, Claus Henn BG, Drumheller T, Curry C, Eskenazi B, 2003. Measurement of pesticides and other toxicants in amniotic fluid as a potential biomarker of prenatal exposure: a validation study. Environ. Health Perspect 111, 1779–1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat AM, Longnecker MP, Koch HM, Swan SH, Hauser R, Goldman LR, et al. , 2015. Optimal exposure biomarkers for nonpersistent chemicals in environmental epidemiology. Environ. Health Perspect 123, A166–A168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco JL, Jover L, 2003. Estimating the generalized concordance correlation coefficient through variance components. Biometrics 59, 849–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castorina R, Bradman A, Fenster L, Barr DB, Bravo R, Vedar MG, et al. , 2010. Comparison of current-use pesticide and other toxicant urinary metabolite levels among pregnant women in the chamacos cohort and nhanes. Environ. Health Perspect 118, 856–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016. National biomonitoring summary. Available: <https://www.cdc.gov/biomonitoring/Chlorpyrifos_BiomonitoringSummary.html > (Accessed July 2017).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017. Fourth national report on human exposure to environmental chemicals. [Google Scholar]

- Engel SM, Berkowitz GS, Barr DB, Teitelbaum SL, Siskind J, Meisel SJ, et al. , 2007. Prenatal organophosphate metabolite and organochlorine levels and performance on the brazelton neonatal behavioral assessment scale in a multiethnic pregnancy cohort. Am. J. Epidemiol 165, 1397–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskenazi B, Marks AR, Bradman A, Harley K, Barr DB, Johnson C, et al. , 2007. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and neurodevelopment in young mexican-american children. Environ. Health Perspect 115, 792–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry GZ, Meeker JD, Sanchez BN, Barr DB, Panuwet P, Bellinger D, et al. , 2014. Urinary 3,5,6-trichloro-2-pyridinol (tcpy) in pregnant women from mexico city: distribution, temporal variability, and relationship with child attention and hyperactivity. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 217, 405–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser R, Meeker JD, Park S, Silva MJ, Calafat AM, 2004. Temporal variability of urinary phthalate metabolite levels in men of reproductive age. Environ. Health Perspect 112, 1734–1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton MK, Kahn LG, Perera F, Barr DB, Rauh V, 2012. Does the home environment and the sex of the child modify the adverse effects of prenatal exposure to chlorpyrifos on child working memory? Neurotoxicol. Teratol 34, 534–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, 2006. Correlation coefficients in medical research: from product moment correlation to the odds ratio. Stat. Methods Med. Res 15, 525–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG, 1977. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrigan PJ, Claudio L, Markowitz SB, Berkowitz GS, Brenner BL, Romero H, et al. , 1999. Pesticides and inner-city children: exposures, risks, and prevention. Environ. Health Perspect 107, 431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng G, Kuhn KH, Idel H, 1997. Biological monitoring of pyrethroids in blood and pyrethroid metabolites in urine: applications and limitations. Sci. Total Environ 199, 173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Barr DB, Pearson M, Bartell S, Bravo R, 2006a. A longitudinal approach to assessing urban and suburban children’s exposure to pyrethroid pesticides. Environ. HealthPerspect 114, 1419–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Toepel K, Irish R, Fenske RA, Barr DB, Bravo R, 2006b. Organic diets significantly lower children’s dietary exposure to organophosphorus pesticides. Environ. Health Perspect 114, 260–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks AR, Harley K, Bradman A, Kogut K, Barr DB, Johnson C, et al. , 2010. Organophosphate pesticide exposure and attention in young mexican-american children: the chamacos study. Environ. Health Perspect 118, 1768–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker JD, Barr DB, Ryan L, Herrick RF, Bennett DH, Bravo R, et al. , 2005. Temporal variability of urinary levels of nonpersistent insecticides in adult men. J. Expo. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol 15, 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MK, Wilson NK, Chuang JC, 2014. Exposures of 129 preschool children to organochlorines, organophosphates, pyrethroids, and acid herbicides at their homes and daycares in north carolina. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 11, 3743–3764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MK, Sobus JR, Barr DB, Croghan CW, Chen FL, Walker R, et al. , 2016. Temporal variability of pyrethroid metabolite levels in bedtime, morning, and 24-h urine samples for 50 adults in north carolina. Environ. Res 144, 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson AO, Baker SE, Nguyen JV, Romanoff LC, Udunka SO, Walker RD, et al. , 2004. A liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry multiresidue method for quantification of specific metabolites of organophosphorus pesticides, synthetic pyrethroids, selected herbicides, and deet in human urine. Anal. Chem. 76, 2453–2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozonoff S, Young GS, Carter A, Messinger D, Yirmiya N, Zwaigenbaum L, et al. , 2011. Recurrence risk for autism spectrum disorders: a baby siblings research consortium study. Pediatrics 128, e488–e495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrier F, Giorgis-Allemand L, Slama R, Philippat C, 2016. Within-subject pooling of biological samples to reduce exposure misclassification in biomarker-based studies. Epidemiol. (Camb., Mass) 27, 378–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauh VA, Garfinkel R, Perera FP, Andrews HF, Hoepner L, Barr DB, et al. , 2006. Impact of prenatal chlorpyrifos exposure on neurodevelopment in the first 3 years of life among inner-city children. Pediatrics 118, e1845–e1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts EM, English PB, Grether JK, Windham GC, Somberg L, Wolff C, 2007. Maternal residence near agricultural pesticide applications and autism spectrum disorders among children in the california central valley. Environ. Health Perspect 115, 1482–1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc, 2016. Sas 9.4. Carny, NC. [Google Scholar]

- Schisterman EF, Vexler A, 2008. To pool or not to pool, from whether to when: applications of pooling to biospecimens subject to a limit of detection. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol 22, 486–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer TJ, Meyer DA, Crofton KM, 2005. Developmental neurotoxicity of pyrethroid insecticides: critical review and future research needs. Environ. Health Perspect 113, 123–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton JF, Geraghty EM, Tancredi DJ, Delwiche LD, Schmidt RJ, Ritz B, et al. , 2014. Neurodevelopmental disorders and prenatal residential proximity to agricultural pesticides: the charge study. Environ. Health Perspect [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soderlund DM, Clark JM, Sheets LP, Mullin LS, Piccirillo VJ, Sargent D, et al. , 2002. Mechanisms of pyrethroid neurotoxicity: implications for cumulative risk assessment. Toxicology 171, 3–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trunnelle KJ, Bennett DH, Tulve N, Clifton MS, Davis M, Calafat A, et al. , 2014. Urinary pyrethroid and chlorpyrifos metabolite concentrations in northern california families and their relationship to indoor residential insecticide levels, part of superb. Environ. Sci. Technol [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2000. Chlorpyrifos Revised Risk Assessment and Agreement with Registrants. Office of Prevention, Pesticides, and Toxic Substances, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins DJ, Fortenberry GZ, Sanchez BN, Barr DB, Panuwet P, Schnaas L, et al. , 2016. Urinary 3-phenoxybenzoic acid (3-pba) levels among pregnant women in mexico city: distribution and relationships with child neurodevelopment. Environ. Res 147, 307–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff TJ, Zota AR, Schwartz JM, 2011. Environmental chemicals in pregnant women in the united states: nhanes 2003–2004. Environ. Health Perspect 119, 878–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.