Graphical abstract

Abbreviations: KGR, Kaempferia galanga rhizome; EPMC, Ethyl p-methoxy cinnamate; ROS, Reactive oxygen species; TMS, Tetramethylsilane

Keywords: Anti-nutritional composition, HPLC-PDA analysis, Medicinal spices, Zingiberaceae

Highlights

-

•

Aromatic ginger is rich in essential nutrients showing potential chemopreventive potential.

-

•

Dried aromatic ginger and its hydro-distillate contains EPMC, 2.24% and 52.54%, respectively.

-

•

In-vitro antiproliferative actions of K. galanga assessed towards nine human cell lines.

-

•

Ethyl para-methoxycinnamate (EPMC) identified as most active against WRL-68 and MDA-MB-231.

-

•

EPMC inhibit intracellular ROS production and protect cell from oxidative damage.

Abstract

Aromatic ginger (Kaempferia galanga L) is native to India and believed to be originated in Burma. Despite substantial uses in a pickle and south-east Asian cuisines, aromatic ginger is chemically less studied than white and red ginger. Multi-directional investigations have been performed to evaluate chemical composition, nutritional values, ameliorative and protective potential of aromatic ginger (Kaempferia galanga) rhizome (KGR). Macro and micro components analysis confirmed that KGR contains protein, fiber, and high amount of essential minerals (potassium, phosphorous, and magnesium) along with appreciable amounts of iron, manganese, zinc, cobalt, and nickel. The anti-proliferative potential of KGR evaluated nine human cell lines. We have evaluated the anti-proliferative potential of hydrodistillate, extract, and key compound isolated from KGR on nine human cancer cell line and also reporting the safety to normal peritoneal macrophage cells. The current study demonstrates the anticancer potential of the KGR on MDA-MB-231 and WRL-68 cells. Very likely, results can be extrapolated to an animal or human system. Ethyl p-methoxy cinnamate (EPMC) was responsible for inhibiting the proliferation action which varied in a tested cell by intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. The present study demonstrates KGR as safe and high energy value medicinal spices with chemo-preventive action, without toxic phytochemicals, and tolerable other anti-nutritional factors.

1. Introduction

Kaempferia galanga L. a rhizomatous medicinal plant belongs to Zingiberaceae family, locally called as Chandramulika, Karchoor, sugandhvacha, resurrection lily, and aromatic ginger. It is mostly cultivated in south-east Asian countries viz. China, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and India [1]. India has wide variety of Zingiberaceae plants with the existence of 20 genera (more than 200 species) out of known 53 genera (about 1200 species). A variety of medicinal and culinary uses of K. galanga for health benefits, food, and nutritional purposes are well documented [2]. People use aromatic ginger as a medicinal spice in India, China, and other south-east Asian cuisines. A large population consumes it as pickles with health benefits. However, scientific study on its practical usage with defined nutritional and safety status is yet to be unveiled.

The development of novel health products with a new concept of combination, selective plant bioactive or “whole foods” have become an increasingly attractive area of research. ‘Beras Kencur’ is a popular Java beverage prepared from the K. galanga tubers [3]. In Traditional Chinese Medicines (TCM), the plant is used to treat cholera, contusion, constipation, and stomachache [4]. In Thailand, it has been used for menstrual disorder and dyspepsia. Traditionally, the rhizomes have also been used to treat several ailments, e.g. fever, amoebiasis, bruise, dandruff, furuncle, headache, rheumatism, toothache, abdominal pain, cold, and chest pain [5]. The essential oil from both rhizome and leaves is used in Bangladesh for fragrance in vinegar, hair washes, cosmetic powders, flavoring the foodstuffs, and beverages [6]. In Indonesia and Malaysia, traditional herbal preparation, known as ‘Makjun’ and ‘Jamu’, are consumed frequently for beneficial health effect. While, Indian Ayurvedic formulations such as Karpuardyarka, Karchuradichurna, Sutasekara rasa, Karchuratailam, and Nalpamaraditailam, used for the treatment of muscular swelling and rheumatism also consisting of KG rhizomes [1]. In addition to its traditional use in south-east countries, a number of experimental studies have also demonstrated that K. galanga have antioxidant [7], cytotoxic [8], anti-inflammatory [9], sedative, [10], vasorelaxant [11], anti-angiogenic, [12], antinociceptive [1], and wound healing [13] activities. Pharmacological activities of KGR are mainly due to the presence of secondary metabolites of different nature [11,14,15]. Ethyl-p- methoxycinnamate (EPMC) is the key compound of KGR has been reported as a bioactive secondary metabolite of KGR [16].

Despite centuries-old culinary and traditional ethnomedicinal usage, development of KGR based functional food could not be possible. The reports on safety and risk assessment of K. galanga preparations is scarce except presence of some harmful alkenylbenzenes in “Jamu” preparations [17,18]. The efficacy with defined mode of action is still a major concern. However, some efforts are available which either showing the proximate nutritional values of KGR [[19], [20], [21]] or preliminary cytotoxicity. Here we report a systematic investigation of KGR on nutritional (proximate chemicals, flavor, fragrance, and minerals-metals profiles), anti-nutritional properties and, the chemical composition of KGR hydrodistilate. Anti-proliferative study on nine available cancer cell lines, with the antioxidant potential of its major bioactive isolate, has been investigated. Additionally, the anti-proliferative action of K. galanga has been examined in-vitro against WRL-68, A549, HaCaT, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, COLO-201, K562, CHANG, Raji and, J774A.1 cancer cell lines. The biocompatible safety of the KGR has also been evaluated to investigate the protective effect towards endotoxins in LPS-stimulated mice peritoneal normal macrophage cell viability.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Plant material

Rhizomes of Kaempferia galanga L. procured from Hamirpur village of Bankura district near to Asansol (West Bengal), India. A voucher specimen of rhizome has been submitted at the CIMAP herbarium (CIMAP-10610) in Lucknow. Plant material was further authenticated by Taxonomy and Pharmacognosy Department of CIMAP. Rhizomes were washed with clean water, shade dried and stored in sealed airtight polybags at room temperature.

2.2. Chemicals and reference compounds

Solvents viz. methanol, chloroform, dichloromethane, acetone, hexane, and reagents of analytical or HPLC grade procured from E. Merck Ltd., Mumbai, India. The NMR spectra recorded in 300 MHz Bruker Avance instrument by using CDCl3 as the solvent with tetramethylsilane (TMS) as an internal standard. DEPT experiment preformed for the determination of carbon atom multiplicity. Spectra of DEPT along with 13C NMR were recorded at 75.47 MHz. Other NMR experiments like COSY, HSQC, and HMBC were done by using standard Bruker pulse programs. IR spectra recorded on a Perkin–Elmer Spectrum BX spectrophotometer. ESI mass spectra obtained on Shimadzu ESI-MS spectrometer (LC-MS2010EV).

2.3. Apparatus

Nexera-XR (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) composed of LC-20ADXR pumps, Autosampler SIL-20AC, column oven CTO-10ASVP, and SPD- M20A diode array detector used for chromatography. LabSolution software (Shimadzu, Japan) used for data acquisition and analysis. Solvents were degassed for 15 min through ultrasonication (Microclean-109, Oscar Ultrasonics, Mumbai, India 30.0 × 25.0 × 12.5 cm, 34 ± 3 kHz, PZT Sandwich type six transducer, 250 W). Solvent filtration unit (Millipore, USA) with 0.45 μm nylon membrane used for filtration of all the samples and the mobile phase. NMR spectra were recorded in CDCl3 using 300 MHz spectrophotometer (Avance, Bruker, Switzerland).

2.4. Sample preparation and isolation of bioactive compound

K. galanga rhizome (KGR) was grounded coarsely in a mixer grinder (Philips, India). Powdered KGR (250 g) was hydro distilled in Clevenger apparatus at 100–105 °C for about 6 h. The condensed hydrodistillate separated and stored at −4 °C until further analysis using GC and GC/MS following the method [14]. The trans-ethyl para methoxycinnamate (EPMC) was separated and purified from oil by crystallization method. Compound identification and their structure elucidation done by various spectroscopic techniques such as 1H-NMR, IR, COSY HMQC, and HMBC. The spectral characteristics matched with the reported data [16].

2.5. Quantification of EPMC in K. galanga extracts

Extraction of KGR, with different polarity of solvents, was performed by overnight cold percolation method. Quantification of EPMC in different extracts of KGR was performed at 30 °C by reverse-phase HPLC using a Symmetry column C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 μm). Solvent A (water) and solvent B (acetonitrile) (40:60, v/v) were used as mobile phase. The elution rate fixed at 1.0 mL/min. While injection volume set at 20 μL. Chromatographic data acquisition captured in the range of 200–400 nm, Quantification done at UV maxima of the compound i.e. 308 nm. The comparative HPLC chromatogram is demonstrating the extraction efficiency of EPMC from KGR by different solvents.

2.6. Physicochemical analysis of rhizome hydrodistilate

The oil content determined through Hydrodistillation on Clevenger apparatus, refractive index on refractometer (Atago RX-7000α model), specific gravity on specific gravity meter (KEM, DA-500), optical rotation on polarimeter (Horiba sepa-300). The acid value, saponification value, and peroxide value hydrodistilate analyzed according to the standard methods [22].

2.7. Proximate analysis of rhizome

Nutritional parameters of dried powdered K. galanga rhizome were analyzed following the standard methods [22] unless indicated otherwise. The proximate composition, e.g., moisture (AOAC method 925.16), crude fat (method 920.85), fiber (method 991.43), and protein (method 920.87), and ash (method 923.03) were estimated. Total carbohydrate content was calculated by standard equation: carbohydrate (%) = 100 − (total protein % + total fat % + moisture % + ash %). The energy value of the rhizome in kcal/100 g was determined by the protocol described by FAO (2003) [2] and calculated by the formula.

Energy value (kcal/100 g) = (crude protein % × 4.0) + (crude carbohydrate % × 4.0) + (crude fat % × 9.0)

2.8. Determination of Anti-nutritional factors (ANFs)

Quantitative determination of total phenolics, tannins, saponins, phytic acid, alkaloids, oxalate sand cyanide contents estimated following the standard methods [22].

2.9. Analysis of rhizome for mineral and heavy metals

For the mineral and trace elements analysis, dried and powdered rhizome samples digested in di-acid i.e. nitric acid and per-chloric acid mixture (10:4, v/v) at 180–250 °C. Samples were analyzed by inductively coupled plasma with atomic emission spectrometry (ICP-AES, Perkin Elmer, USA). Sodium and potassium estimated using emission flame photometer.

2.10. In-vitro evaluation anti-proliferative potential of KGR (Kaempferia galanga rhizome)

2.10.1. Sample preparation, cell lines, and culture media

Coarse powder of dried rhizome extracted for a day with methanol at room temperature and filtered. The filtrate concentrated under vacuum at 40 °C which resulted in the dark brownish extract. The methanol extract of KGR and its hydro-distillate along with EPMC tested for possible chemo-therapeutic adjuvants. The chemoprevention action was evaluated in nine human cancer cell lines viz. WRL-68 (hepatocellular carcinoma), HaCaT (keratinocytes cells), MCF-7 (estrogen receptor-positive breast adenocarcinoma), MDA-MB-231 (estrogen receptor-negative breast carcinoma), COLO-201 (colon carcinoma), K562 (leukemia carcinoma), CHANG (liver cell line), A549 (lung carcinoma), Raji (Burkitt's lymphoma cell line), and J774A.1 (peritoneal macrophage cell line) obtained from NCCS, Pune, India. Mentioned cell lines cultured in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) with 1% antibiotic/antimycotic and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) in the CO2 incubator (5% CO2, 95% humidity at 37 °C). While for in-vitro survival test, mouse peritoneal macrophage cell line (J774A.1) purchased from National Centre for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India.

2.10.2. Cell viability and anti-proliferative activity

The biocompatible safety studied in normal peritoneal macrophage cells (MTT) assay by using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium [23]. In-brief, cell was seeded on the wells, by inoculation of the cell suspension using 100 μL to each well at the density of 1.5 × 106 cells per well. After incubation, wait for 24 h. Different concentrations of treatments (10–50 μg/mL) were performed and incubated for 24 h. Afterward, 10 μL/well MTT dye (5 mg/mL) was mixed and further incubated for four hours in the dark. Thereafter, the MTT dye was removed, and 100 μL/well DMSO was added to each well with the help of a pipette. The absorbance was recorded at 570 nm on a SpectraMax 190 Microplate Elisa Reader (Molecular Devices Inc., Sunnyvale, USA). The percent survival and cytotoxicity of the cells calculated by the following formula.

| Percent survival = (ODsample – ODzero-day) / (ODcontrol – ODzero-day) × 100. |

| Percentage of cytotoxicity = 100 - Percentage of survival |

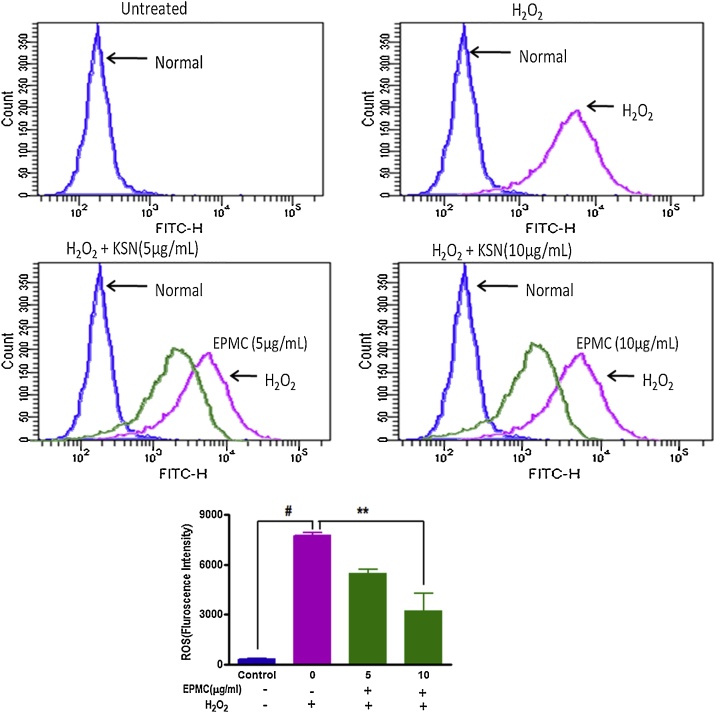

2.10.3. Estimation of intracellular ROS (reactive oxygen species)

DCFH-DA (5, 6-carboxy-2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate) dye used in flow cytometer for intercellular ROS estimation in mouse peritoneal macrophage cells following the method [23]. Briefly, cells were seeded in 24-well plates at density 1 × 106 cells/well and further incubated in the presence or absence of EPMC (5 and 10 μg/mL) for 24 h. The cells were exposed to 100 μM H2O2 for one hour. After incubation, the cells were washed two times with PBS and incubated for 30 min with DCF-DA (10 μM) at 37 °C. At the end of incubation, cells re-suspended in 300 μl of PBS and analyzed by flow cytometer (LSR-II, BD Biosciences, USA). Cells treated with H2O2 without EPMC pre-treatment served as controls.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Chemical studies

3.1.1. Standardization and chemical characterization of KGR

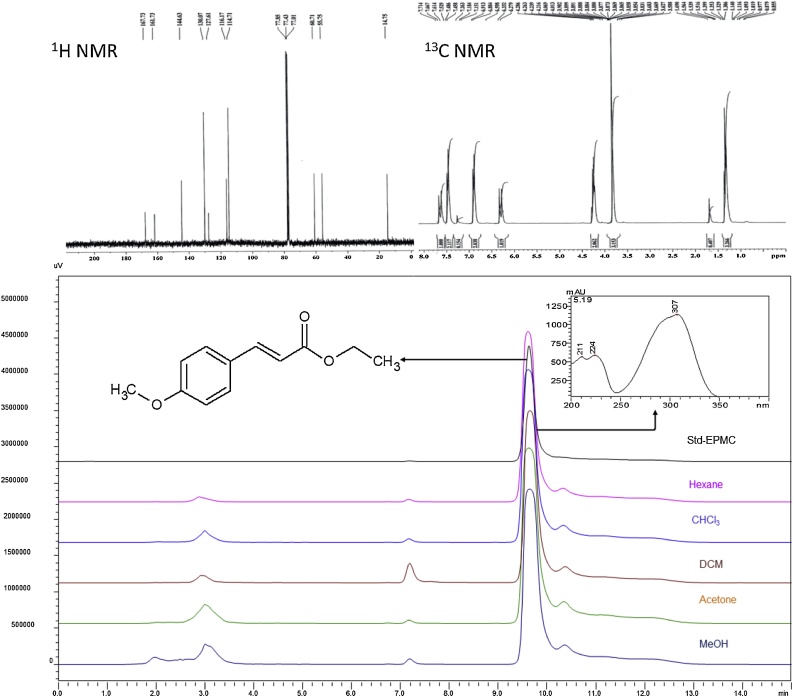

The chemical characterization of hydrodistillate of K. galanga performed by the method [24] revealed the presence of trans-ethyl-p-methoxycinnamate (52.54% relative composition) as a major compound. While the methanol extract characterized by an in-house developed HPLC method. The presence of EPMC in methanol (2.15%, w/w) and other organic solvents is evidenced. Data on extraction efficiency of EPMC in different solvents reveals that acetone is the most suitable solvent (yield 2.24%, w/w) for extraction while followed methanol (2.15%, w/w), chloroform (1.99%, w/w), dichloro-methane (1.94%, w/w), and hexane (1.85%, w/w) (Fig. 1). However, we have isolated EPMC from KGR by a single step novel clean process without the use of column chromatography (process patent filed-data not shown).

Fig. 1.

HPLC fingerprinting chromatogram showing EPMC content in different extracts of Kaempferia galanga rhizome.

The major compound of KGR was characterized as EPMC showing three characteristic UV maxima at 210, 224, and 307 nm. Chemically functional groups of the molecule are determined by Infrared spectroscopy. The peaks indicated the presence of the carbonyl group (1706), aromatic region (1601.9 & 1629.9) and an alkene unsaturation (3386.90). A broad singlet at 3.82 in 1H NMR spectrum was due to small coupling, and the HSQC relation between 3.82 and 55.75 suggested it to be a methoxy group. The quartet coupling of CH2 (4′) shows a signal at 4.21 confirming the presence of CH3 (5′) group at its adjacent that can be further confirmed by triplet coupling of 3H at 1.32. The signals at 6.33 and 7.66 show the doublet of 1′ and 2′ carbon of 1-H. The protons at 3 & 5 positions gave doublet at 6.88 of 2H while 2 & 6 protons gave doublet signal at 7.18 of 2H. (Fig. 1)

The 13C NMR spectrum signals indicated for the presence of aromatic, an ester group, an alkene carbon, and alkyl group carbons. The absence of 3 peaks 167.73(3′), 161.73(4) & 127.61(1) in DEPT-135 indicates the presence of 3 quartet carbon in the structure. The HMBC coupling of 167.73-4.21 indicates the presence of the carbonyl group and 161.2-3.82 shows that the methoxy group connected with aromatic carbon 4. The negative peak at 60.31(4′) in DEPT-135 confirms the presence of —CH2 that is also clear from HMBC 1H-13C correlation. The equivalent carbons 3 and 5 give a signal of 116.17 while 2 and 6 at 127.61. The alkene carbon at 1′ gives a signal at 144.63, and the carbon 2′ adjacent to carbonyl occurs at 114.71. The CH2 (4′) and CH3 (5′) gives signals at 55.75 & 14.75 respectively. The NMR data and ESI mass at m/z 229 [M + Na] +, established a molecular formula of C12H14O3. Thus, the isolated compound was found to be trans-ethyl-p-methoxycinnamate. The spectral characteristics matched with the reported data [25].

3.2. GC/MS and Physicochemical characteristic of hydro-distillate

Physiochemical properties of the KGR oil depicted in Table 1. GC-FID and GC/MS have been used for chemical characterization of KGR hydro-distillate. Total fifty-four constituents characterized which amounting to 92.77%, of the KGR volatile organic compounds (VOCs). VOCs were Trans ethyl-p-methoxycinnamate (52.54%), trans-Ethyl cinnamate (24.98%), 1,8-Cineole (4.14%), 3-Carene (3.94%), dihydroterpineol (1.84%), α-Terpineol (1.64%), and Camphene (1.02%).

Table 1.

Physicochemical values of the hydro-distillate of K. galanga rhizome.

| Parameters | Values/characteristics |

|---|---|

| Oil yield | 1.30 ± .02% |

| Major metabolites | Trans ethyl p-methoxycinnamate, Trans ethyl cinnamate, 1,8-Cineole 3-Carene, |

| Colour | Light yellow |

| Smell | Camphoraceous |

| Physical state | Viscous |

| Saponification value | 106.59 ± 2.09 |

| Iodine value | 107.00 ± 2.18 |

| Acid value | 2.24 ± 0.05 |

| Peroxide value | 22 ± 0.49 |

| Optical rotation | −0.7237 D at 21.7 °C |

| Refractive index | 1.55611 at 20 °C |

| Specific gravity | 1.0268 at 25 °C |

Saponification value (SV) and iodine value (IV) are the qualitative parameters which denote the average molecular mass of fatty acid and degree of unsaturation in the oil sample. The SV (107) of KGR oil is lower than reported FAO Codex standards of vegetable oil. However, IV (107) were equivalent to the reference value of arachis, cottonseed, grape seed, maize, and mustard oils [26]. Lower SV of KGR oil suggests that the average molecular weight of fatty acids of KGR oil is lower or less number of ester bonds than common vegetable oil. It indicates that the fat molecules of KGR oil did not interact with each other. The low iodine values of KGR oil may be responsible for its susceptible storage stability due to oxidative and chemical changes.

3.3. Proximate compositions and energy content of KGR

Potential nutritional attributes of K. galanga rhizomes has been summarised (Table 2). Dry matter analysis and moisture content determination are two critical parameters which directly affects the nutritional content of KGR. The lower value of moisture (11.08%) content is advantageous for storage/drying purposes and may be useful to increase the shelf life. Rhizome was found to be very rich in carbohydrates (72.04%) with an appreciable amount of fiber (7.93%). The carbohydrate content was found to be comparable with some reported common cereals [27], higher than Zingiberaceae [20,21], and leguminous [28] plants. Because of zero calorific value, dietary fiber has many beneficial action related to indigestibility and constipation in the intestine [29]. While low-fat (1.66%) in KGR is another advantage that would be beneficial for overweight and fat restricted people. KGR with an affable amount of protein (5.92%) was estimated to supplement the substantial amount of energy (331 kcal/100 g). Not only the energy but other proximate parameters of KGR of presently used are superior to the reported rhizomes [20,21] of thirteen plant species of Zingiberaceae family except total protein and fiber content of Curcuma zedoaria. Overall proximate composition and calorific status of the KGR demonstrated that this culinary spice is rich in essential nutrients and could be a healthy ingredient of the human diet.

Table 2.

Nutritional composition and anti-nutritional factors of Kaempferia rhizome on a dry weight basis.

| Parameter | Content |

|---|---|

| Nutritional composition (g/100 g, DW*) | |

| Ash content | 6.35 ± 0.13 |

| Moisture content | 11.08 ± 0.21 |

| Crude fat | 1.66 ± 0.03 |

| Crude protein | 5.92 ± 0.13 |

| Crude fiber | 7.93 ± 0.14 |

| Total carbohydrate | 72.04 ± 1.05 |

| Calorific value (kcal/100 g) | 331.49 ± 8.38 |

| Ant-nutrient factors (mg/100 g, DW*) | |

| Total phenolics | 12.13 ± 0.94 |

| Saponins | 6.62 ± 0.72 |

| Phytic acid | 66.67 ± 2.35 |

| Alkaloids | 3.30 ± 0.24 |

| Tannins | 1.18 ± 0.01 |

| Oxalate | 30.09 ± 0.70 |

| Total cyanide | ND# |

DW-Dry weight.

ND-Not detected.

3.4. Anti-nutritional factors (ANFs)

Screening of ANFs in the KGR is summarized in above Table 2. Oxalate and phytic acid content were less than major cereals, legumes, nuts, oilseeds, and other ginger species [[30], [31], [32]]. Most of the ANFs have a significant role in plant defense. Phytic acid is a unique example of an anti-nutrient reported to be beneficial against kidney stones [33] and colorectal cancer [34]. Similarly, no cyanogenic glycosides reported in the rhizomes of gingers including KGR. Other ANFs such as tannins, phytate, and saponins are of little significance when rhizomes processed properly.

3.5. Essential mineral and toxic metal status of KGR

Powdered rhizome samples were analyzed targeting eleven essential minerals and six heavy metals compared with reported data (Table 3). KGR contain beneficial nutrients viz. potassium, phosphorous, and magnesium in higher concentration with appreciable amounts of iron, manganese, zinc, cobalt, and nickel. Potassium, phosphorous, and magnesium plays a crucial role in the bone skeleton, biochemical reactions, and energy metabolism [35]. Additionally, KGR can exhibit therapeutic action against growth disorders and anemia due to the availability of iron, manganese, and other mineral antioxidants, e.g., zinc, cobalt, and nickel. The variability in the mineral content of KGR between different countries, e.g., Malaysia, China, and Bangladesh and also within the country can be observed (Table 3). The variation in mineral contents in KGR, dependent on many factors, e.g. availability in soil, soil compositions, genetic and environment (G × E) interactions like any other plant.

Table 3.

Comparative data on mineral and metal composition of aromatic ginger of different origin.

| Mineral and metals content in K. galanga rhizome of different origin |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Asansol, West Bengal, India† | Kelantan, Malaysia† | Bangi, Malaysia†, * | Kerala, India† | Shuangjiao, Guangdong, China† | Chittagong, Bangladesh‡, * |

| Minerals (ppm) | ||||||

| Sodium | 43.26 ± 0.78 | 6970 ± 100 | 71.50 | 1150 ± 10 | ||

| Potassium | 7500 ± 15 | 5000 ± 200 | 1375.00 | 11050 ± 20 | ||

| Calcium | 137.08 ± 2.46 | 415.40 | 2600 ± 100 | 508.20 | 3000 ± 40 | |

| Magnesium | 520.49 ± 9.27 | 192.00 | 3700 ± 200 | 313.4 | 488.79 | 1350 ± 50 |

| Iron | 55.54 ± 1.16 | 17.43 | 42 ± 12 | 18.90 | 7.83 | 192 ± 4.24 |

| Zinc | 0.88 ± 0.02 | 1.90 | 85 ± 8 | 14.52 | 8.22 | 12 ± 0.00 |

| Manganese | 9.23 ± 0.17 | 1.73 | 79.90 | 63.41 | 68 ± 1.41 | |

| Copper | BDL* | 0.792 | 0.72 | 20 ± 1.41 | ||

| Cobalt | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||

| Nickel | 0.31 ± .02 | 0.251 | 0.52 | |||

| Phosphorus | 6400 ± 20 | 3260 ± 20 | ||||

| Metals(ppm) | ||||||

| Aluminum | 24.77 ± 0.043 | |||||

| Chromium | 0.12 ± 0.01 | 0.761 | 0.17 | |||

| Cadmium | BDL# | 0.03 | ||||

| Lead | BDL# | 0.48 | ||||

| Arsenic | BDL# | |||||

| Mercury | BDL# | |||||

| Reference | Present study | [42] | [21] | [19] | [43] | [20] |

Dry weight basis.

Fresh weight basis.

Value converted from reported data (g/100 g, mg/100 g, and %) for uniform data representation.

BDL-Below detection limit; Values presented as Mean ± SD.

KGR was safe with no critical load of toxic heavy metals. The metal concentration in plants governed by many factors but mainly due to geochemical environment. The heavy metals status in a number of the medicinal plants has already been reported [36,37]. KGR has a better accumulation of essential micronutrients such as Cu, Fe, Ni, Zn, Mg, and Mn (Table 3). However, the low concentration of aluminum (24.77 ppm) and chromium (0.12 ppm) was much lower than the maximum permissible limit [38]. It is also worth to mention that such low concentration of aluminum in KGR is insignificant because of tolerable weekly intake of 1.0 mg/kg body weight/week as per FAO/WHO expert committee recommendations. Monitoring of heavy metals in medicinal plants and spices used as a phytoceutical/functional food for health-promoting benefits [39]. Moderate to severe effects of the above mentioned toxic heavy metals are well reported when consumed [40,41]. Since the chemical composition of medicinal food plants varies and governs by many factors such as cultivars, soil and climatic conditions, postharvest, and storage conditions [15].

3.6. Biological activity and safety studies

3.6.1. Anti-proliferative and inhibition of intracellular ROS production

Valorization in the raw food or waste part in terms of their chemoprevention potential is a new strategy for functional food development. Recently, Dracocephalum kotschyi aerial part and Vitis vinifera stem have shown chemopreventive action in lung, colon, breast, renal, and thyroid cancer cell predominantly due to flavonoids [44,45]. Here, we report the anti-proliferative action of K. galanga rhizome (KGR). Some secondary metabolites of diverse nature have already reported from the KGR [14]. EPMC is the major phytochemical of KGR.Therefore efforts were made to evaluate its pharmacological and therapeutic potential [13,20,46,47]. Only limited data of KGR anti-proliferative potential targeting single cell line is reported so far [48]. The anti-proliferative effect of methanol extract, hydro-distillate, and EPMC on organ-specific cancer cell lines (WRL-68, A549, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, COLO-201, K562, Raji, HaCaT, and CHANG) evaluated using MTT assay. A decrease in the growth of cells has been observed in dose-dependent manner. The highest concentration, i.e., 50 μg/mL of EPMC, hydro-distillate, and extract have inhibited the proliferation of cancer cell line (MDA-MB-231) by 48%, 43%, and 36%, respectively. While EPMC, hydro-distillate, and extract at 50 μg/mL have inhibited the growth of WRL-68 by 37%, 42%, 46%, respectively (Fig. 2). Data suggest that the inhibitory potential of KGR was primarily due to EPMC against breast and hepatocellular carcinoma which needs further detail studies. However previously, a diterpenoid from KGR has exhibited good cytotoxicity against HeLa and HSC-2 cancer cells [47]. Cell proliferation govern by many factors. It is well established that dietary flavonoids exhibit anti-proliferative action due to their intercellular ROS inhibition or scavenging potential. Recently, the role of CYP1 family enzymes (cytochrome P450) in breast cancer and cell surface glycoconjugation in oral mucosal carcinogenesis has also been envisaged [49,50].

Fig. 2.

Concentration responses of a) methanol extract b) hydro-distillate and c) Compound (EPMC) on proliferation on targeted human cancer cell lines.

In order to define the mechanism of action of KGR extract and hydrodistillate, the role of EPMC has also been investigated by assessment of the protection of oxidative cellular damage. Results indicate that EPMC pre-treatment inhibited H2O2-induced ROS production using a cell-permeable, as evident by oxidation-sensitive dye (DCFH-DA). Intracellular ROS production increased in H2O2 stimulated cells as compare to normal cells. The increased ROS production inhibited by EPMC pre-treatment in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3). The protective action was dose-dependent and at a higher tested concentration (10 μg/mL). EPMC inhibited more than 50% ROS production of the cell stimulated with H2O2. It can be concluded that EPMC is not only responsible for the distinct aroma and flavor of KGR but also protect from oxidative cellular damage thus can use as a dietary chemopreventive agent in adjunct chemotherapy.

Fig. 3.

Flow cytometry results are showing the ROS production in the J774.1 macrophages upon pretreatment of EPMC. Original recordings of DCF fluorescence intensity reflecting the ROS level. Blue-Normal control, Violet- H2O2 as positive control, and Green- EPMC (5 and 10 μg/mL). Three separate experiments were performed. A representative example has been shown.

3.6.2. Safety assessment

Data of in-vitro effect of methanol extract of KGR, hydro-distillate and it's major bioactive, i.e., EPMC on cell viability in peritoneal macrophage cells presented (Table 4). The change in % live cells between tested concentrations of the normal cells was non-significant (p > 0.05). The conversion of MTT estimates the mitochondrial activity of the live cell into formazan crystals [51]. Results demonstrate the non-toxic nature of extract, hydro-distillate, and EPMC, provides new opportunities for safe use either therapeutics as well as nutritional applications.

Table 4.

Biocompatibility and cell safety of EPMC- a major bioactive of KGR.

| Dose (μg/mL) |

*Cell viability (%) (Mean ± SE) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| #KGR-MeOH Extract | KGR-Hydro-distillate | EPMC | |

| 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 5 | 100.81 ± 4.22 | 98.48 ± 5.26 | 101.04 ± 6.69 |

| 10 | 98.56 ± 4.63 | 98.32 ± 4.93 | 97.20 ± 7.17 |

| 20 | 99.85 ± 7.38 | 97.64 ± 4.87 | 96.51 ± 5.12 |

| 50 | 96.37 ± 6.29 | 97.67 ± 5.63 | 96.85 ± 4.34 |

| 100 | 96.18 ± 5.74 | 97.25 ± 4.39 | 96.73 ± 4.65 |

Peritoneal macrophage cells using MTT assay (detail in material and method section).

KGR-MeOH- K. galanga rhizome methanol extract.

4. Conclusion

Along with medicinally and industrially high valued hydrodistillate [52], KGR contains beneficial nutraceutical properties viz. potassium, phosphorous and magnesium in higher amount with the appreciable quantity of iron, manganese, zinc, cobalt, and nickel. No toxic metals traced in the KGR. High calorific value and carbohydrate content equivalent to some reported cereals and higher than reported Zingiberous plants (except C. zedoaria) and leguminous plants could serve as a healthy and alternative source for supplementing the human diet. A high energy value, good proximate composition and minerals, tolerable anti-nutritional, and absence of cyanogenic glycosides demonstrated that culinary spice has all essential qualities to be developed as a flavored phytoceutical food. Additionally, the inhibition of intracellular ROS production by a key flavoring agent of KGR, i.e., EPMC might be responsible for its protective potential from oxidative damage without any cellular toxicity. EPMC had inhibitory activity against WRL-68 and MDA-MB-231 (ER-negative- Claudin-low) carcinoma cells showing its potential as chemopreventive agent particularly wherein anti-estrogen therapy may not effective. Overall, it is summarized that KGR meets all necessary criteria for the development of flavored functional food and beverage with anti-oxidant and chemopreventive action. It can be incorporated into different flavored food and beverage due to its sensory attributes and medicinal value to enhance the nutritional and phytopharmaceutical value of the food [53].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Authors are thankful to the Director, CSIR-CIMAP for providing the necessary facilities and infrastructure. NS is also acknowledging the UGC, New Delhi for awarding fellowship (UGC-JRF/SRF).

References

- 1.Ridtitid W., Sae-Wong C., Reanmongkol W., Wongnawa M. Antinociceptive activity of the methanolic extract of Kaempferia galanga Linn. in experimental animals. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2008;118(2):225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Preetha T.S., Hemanthakumar A.S., Krishnan P.N. A comprehensive review of Kaempferia galanga L. (Zingiberaceae): a high sought medicinal plant in Tropical Asia. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2016;4(3):270–276. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Limyati D.A., Juniar B.L.L. Jamu Gendong, a kind of traditional medicine in Indonesia: the microbial contamination of its raw materials and endproduct. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1998;63(3):201–208. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00082-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sirirugasa P. Thai Zingiberaceae: species diversity and their uses. International Conference on Biodiversity and Bioresources: Conversation and Utilization. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kanjanapothi D., Panthong A., Lertprasertsuke N., Taesotikul T., Rujjanawate C., Kaewpinit D., Sudthayakorn R., Choochote W., Chaithong U., Jitpakdi A., Pitasawat B. Toxicity of crude rhizome extract of Kaempferia galanga L. (ProhHom.) J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004;90(2):359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman M.M., Amin M.N., Ahamed T., Ali M.R., Habib A. Efficient plant regeneration through somatic embryogenesis from leaf base derived callus of Kaempferia galanga L. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2004;3(6):675–678. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sulaiman S.F., Sajak A.A.B., Ooi K.L., Supriatno, Seow E.M. Effect of solvents in extracting polyphenols and antioxidants of selected raw vegetables. J. Food Anal. 2011;24:506–515. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asmare A., Tullayakorn P., Kesara N.-B. Anticholangiocarcinoma activity and toxicity of the Kaempferia galanga Linn. rhizome ethanolic extract. BMC Complem. Altern. Med. 2017;17(1):213–223. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1713-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Channabasavaiah J.P., Parameshwarappa L.K., Jayesh M., Kutty N.G. Extraction, characterization and evaluation of Kaempferia galanga L. (Zingiberaceae) rhizome extracts against acute and chronic inflammation in rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016;194:434–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ali M.S., Dash P.R., Nasrin M. Study of sedative activity of different extracts of Kaempferia galanga in Swiss albino mice. BMC Complem. Altern. Med. 2015;15(1):158–162. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0670-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Othman R., Ibrahim H., Mustafa M.A., Mustafa M.R., Awang K. Bioassay-guided isolation of a vasorelaxant active compound from Kaempferia galanga L. Phytomedicine. 2006;13(1-2):61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He Z.H., Yue G.G.L., Lau C.B.S., Ge W., But P.P.H. Antiangiogenic effects and mechanisms of trans-ethyl p-methoxycinnamate from Kaempferia galanga L. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60(45):11309–11317. doi: 10.1021/jf304169j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shanbhag T.V., Sharma C., Adiga S., Bairy L.K., Shenoy S., Shenoy G. Wound healing activity of alcoholic extract of Kaempferia galanga in wistar rats. Indian J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2006;50(4):384–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raina A.P., Abraham Z. Chemical profiling of essential oil of Kaempferia galanga L. germplasm from India. J. Esssent. Oil. Res. 2016;28(1):29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lal M., Munda S., Dutta S., Baruah J., Pandey S.K. Identification of the new high oil and rhizome yielding variety of Kaempferia galanga (JOR LAB K-1): a highly Important Indigenous medicinal plants of North East India. J. Essent. Oil Bear. Pl. 2017;20(5):1275–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Umar M.I., Asmawi M.Z., Sadikun A., Majid A.M.S.A., Al-Suede F.S.R., Hassan L.E., Altaf R., Ahamed M.B.K. Ethyl-p-methoxycinnamate isolated from kaempferia galanga inhibits inflammation by suppressing interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-a, and angiogenesis by blocking endothelial functions. Clinics. 2014;69(2):134–144. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2014(02)10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suparmi S., Widiastuti D., Wesseling S., Rietjens I.M.C.M. Natural occurrence of genotoxic and carcinogenic alkenylbenzenes in Indonesian jamu and evaluation of consumer risks. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018;118:53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suparmi S., Ginting A.J., Mariyam S., Wesseling S., Rietjens I.M.C.M. Levels of methyleugenol and eugenol in instant herbal beverages available on the Indonesian market and related risk assessment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019;125:467–478. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Indrayan A.K., Agrawal P., Rathi A.K., Shatru A., Agrawal N.K., Tyagi D.K. Nutritive value of some indigenous plant rhizomes resembling Ginger. Nat. Prod. Rad. 2009;8(5):507–513. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanzima Y., Golam K., Shakawat H., Rasida P., Farjana N. Nutritional values of lesser utilized aromatic medicinal plants. Int. Res. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2011;2(1):76–79. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibrahim H., Khalid N., Hussin K. Cultivated gingers of peninsular Malaysia: ultilization profiles and micropropagation. Gard. Bull. (Singapore) 2007;59(1-2):71–88. [Google Scholar]

- 22.AOAC . 17th edition. The Association of Official Analytical Chemists; Gaithersburg, MD, USA: 2000. Official Methods of Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohanty S., srivastava P., Maurya A.K., Cheema H.S., Shanker K., Dhawan S., Darokar M.P., Bawankule D.U. Antimalarial and safety evaluation of Pluchea lanceolata (DC.) Oliv. & Hiern: in-vitro and in-vivo study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013;149(3):797–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong K.C., Ong K.S., Lim C.L. Compositon of the essential oil of rhizomes of kaempferia galanga L. Flavour Frag. J. 1992;7(5):263–266. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Umar M.I., Asmawi M.Z., Sadikun A., Atangwho I.J., Yam M.F., Altaf R., Ahmed A. Bioactivity-guided isolation of Ethyl-p-methoxycinnamate, an anti-inflammatory constituent, from Kaempferia galanga L. extracts. Molecules. 2012;17:8720–8734. doi: 10.3390/molecules17078720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations and the World Health Organization; 2009. Anonymous; Codex Alimentarius Commission. Codex Standard for Named Vegetable Oils (CODEX-STAN 210-1999) pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adewusi S.R.A., Udio J., Osuntogun B.A. Studies on the carbohydrate content of breadfruit (Artocarpus communis Forst) from South-Western Nigeria. Starch. 1995;47(8):289–294. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bolanle A.O., Funmilola A.S., Adedayo A. Proximate analysis, mineral contents, amino acid composition, anti-nutrients, and phytochemical screening of Brachystegia eurycoma Harms and Pipper guineense Schum and Thonn. Am. J. Food Nutr. 2014;2(1):11–17. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eleftheria R., Dimitris A., Rodopi N., Andreous C., John M. Diet and chronic constipation in children: the role of fiber. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1999;28(2):169–174. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199902000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schlemmer U., Frølich W., Prieto R.M., Grases F. Phytate in foods and significance for humans: food sources, intake, processing, bioavailability, protective role and analysis. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2009;53(S2):S330–S375. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andallu B., Radhika B., Suryakantham V. Effect of aswagandha, ginger and mulberry on hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2003;58(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wijekoon M.M.J.O., Karim A.A., Bhat R. Evaluation of nutritional quality of torch ginger (Etlingera elatior Jack.) inflorescence. Int. Food Res. J. 2011;18(4):1415–1420. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grases F., Costa-Bauza A., Prieto R.M. Renal lithiasis and nutrition. Nutr. J. 2006;5(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shafie N., Esa N., Ithnin H., Saad N., Pandurangan A. Pro-apoptotic effect of rice bran inositol hexaphosphate (IP6) on HT-29 colorectal cancer cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14(12):23545–23558. doi: 10.3390/ijms141223545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haddy F.J., Vanhoutte P.M., Feletou M. Role of potassium in regulating blood flow and blood pressure. Am. J. Physiol. 2006;290(3):546–552. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00491.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang X.Y., Fu S.M., Liu H., Chen N., Zhao X.F., Zhang H.Y. Geochemical characteristics of Kaempferia galanga from Guangdong province. J. Guangzhou Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2010;4(15) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bhat R., Kiran K., Arun A.B., Karim A.A. Determination of mineral composition and heavy metal content of some nutraceutically valued plant products. Food Anal. Method. 2010;3(3):181–187. [Google Scholar]

- 38.WHO . 2007. World Health Organization Guidelines for Assessing Quality of Herbal Medicines with Reference to Contaminants and Residues: Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Michaela Z., Juranović C.I. Review–trace determination of potentially toxic elements in (medicinal) plant materials. Anal. Methods. 2017;9(10):1550–1574. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Żukowska J., Biziuk M. Methodological evaluation of method for dietary heavy metal intake. J. Food Sci. 2008;73(2):R21–R29. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2007.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nasiruddin R.M., Jitbanjong T., Masudur R.M. Toxicodynamics of lead, cadmium, mercury and arsenic-induced kidney toxicity and treatment strategy: a mini review. Toxicol. Rep. 2018;5:704–713. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karim S.M.R., Kasthuri L., Nadiatul N.T. Vitamins and mineral contents of ten selected weeds and local plants of Kelantan, Malaysia. Int. J. Biol. Pharm. Allied Sci. 2017;6(2):161–174. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu H., Chang X.Y., Fu S.M., Zhao X.F. Determination of trace elements in Kaempferia galangal L. And soil by ICP-AES. ICBBE 2010. 4th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering, 2010. 2010:1–3. ISSN 2151-7622. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sahpazidou D., Geromichalos G.D., Stagos D., Apostolou A., Haroutounian S.A., Tsatsakis A.M., Tzanakakis G.N., Hayes A.W., Kouretas D. Anticarcinogenic activity of polyphenolic extracts from grape stems against breast, colon, renal and thyroid cancer cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2014;230(2):218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sani T.A., Mohammadpour E., Mohammadi A., Memariani T., Yazdi M.V., Rezaee R., Calina D., Docea A.O., Goumenou M., Etemad L. Cytotoxic and apoptogenic properties of Dracocephalum kotschyi aerial part different fractions on CALU-6 and MEHR-80 lung cancer cell lines. Farmacia. 2017;65(2):189–199. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vaintraub I.A., Lapteva N.A. Colorimetric determination of phytate in unpurified extracts of seeds and the products of their processing. Anal. Biochem. 1988;175(1):227–230. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90382-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swapana N., Tominaga T., Elshamy A.I., Ibrahim M.A.A., Hegazy M.-E.F., Singh C.B., Suenaga M., Imagawa H., Noji M., Umeyama A. Kaemgalangol A: unusual seco-isopimarane diterpenoid from aromatic ginger Kaempferia galanga. Fitoterapia. 2018;129:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Basak S., Sarma G.C., Rangan L. Ethnomedical uses of zingiberaceous plants of Northeast India. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010;132(1):286–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Periyannan V., Veerasamy V. Syringic acid may attenuate the oral mucosal carcinogenesis via improving cell surface glycoconjugation and modifying cytokeratin expression. Toxicol. Rep. 2018;5:1098–1106. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Androutsopoulos V.P., Ruparelia K., Arroo R.R.J., Tsatsakis A.M., Spandidos D.A. CYP1-mediated antiproliferative activity of dietary flavonoids in MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells. Toxicology. 2009;264(3):162–170. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meerloo J.V., Kaspers G.J.L., Cloos J. Cell sensitivity assays: the MTT assay. In: Cree I., editor. Cancer Cell Culture. Methods in Molecular Biology (Methods and Protocols) Humana Press; USA: 2011. pp. 237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Munda S., Saikia P., Lal M. Chemical composition and biological activity of essential oil of Kaempferia galanga: a review. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2018;30(5):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carrasco-González J.A., Serna-Saldívar S.O., Gutiérrez-Uribe J.A. Nutritional composition and nutraceutical properties of the Pleurotus fruiting bodies: potential use as food ingredient. J. Food Anal. 2017;58:69–81. [Google Scholar]