Abstract

Multiple types of Cl−channels regulate smooth muscle excitability and contractility in vascular, gastrointestinal, and airway smooth muscle cells. However, little is known about Cl− channels in detrusor smooth muscle (DSM) cells. Here, we used inside-out single channel and whole cell patch-clamp recordings for detailed biophysical and pharmacological characterizations of Cl− channels in freshly isolated guinea pig DSM cells. The recorded single Cl− channels displayed unique gating with multiple subconductive states, a fully opened single-channel conductance of 164 pS, and a reversal potential of −41.5 mV, which is close to the ECl of −65 mV, confirming preferential permeability to Cl−. The Cl−channel demonstrated strong voltage dependence of activation (half-maximum of mean open probability, V0.5, ~−20 mV) and robust prolonged openings at depolarizing voltages. The channel displayed similar gating when exposed intracellularly to solutions containing Ca2+-free or 1 mM Ca2+. In whole cell patch-clamp recordings, macroscopic current demonstrated outward rectification, inhibitions by 4,4′-diisothiocyano-2,2′-stilbenedisulfonic acid (DIDS) and niflumic acid, and insensitivity to chlorotoxin. The outward current was reversibly reduced by 94% replacement of extracellular Cl− with I−, Br−, or methanesulfonate (MsO−), resulting in anionic permeability sequence: Cl−>Br−>I−>MsO−. While intracellular Ca2+ levels (0, 300 nM, and 1 mM) did not affect the amplitude of Cl− current and outward rectification, high Ca2+ slowed voltage-step current activation at depolarizing voltages. In conclusion, our data reveal for the first time the presence of a Ca2+-independent DIDS and niflumic acid-sensitive, voltage-dependent Cl− channel in the plasma membrane of DSM cells. This channel may be a key regulator of DSM excitability.

Keywords: chloride, detrusor, ion channel, smooth muscle cell, urinary bladder

INTRODUCTION

Detrusor smooth muscle (DSM) cells, which build up the wall of the urinary bladder, exhibit relaxation and contraction that respectively underlie the two critical functions of the urinary bladder: urine storage and voiding. Similar to cardiac and skeletal muscle cells, molecular mechanisms of DSM excitability and contractility involve finely orchestrated spatiotemporal activation/deactivation of multiple ion channel types (for reviews, see Refs. 44 and 45). Several ion channel types have been already identified, characterized, and their roles in DSM excitation-contraction coupling elucidated (44, 45). A vast majority of the identified DSM ion channels are highly selective for cations, including K+, Ca2+, and Na+ conducting channels (44). Several families of DSM K+ channels, including Ca2+-activated K+ (KCa) channels, voltage-gated (KV) channels, inward-rectifying ATP-sensitive K+ (Kir, KATP) channels, and two-pore-domain K+ (K2P) channels, are involved in setting the resting membrane potential and establishing the repolarizing phase of DSM spontaneous action potentials (44, 45). Voltage-gated Ca2+ (Cav1.2 and Cav3.1, Cav3.2, and Cav3.3) channels control Ca2+ influx and shape the upstroke phase of spontaneous action potentials and directly initiate DSM phasic contractions (29, 58). Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, belonging to vanilloid (TRPV1 and TRPV4), canonical (TRPC4), and melastatin (TRPM4) families, have been detected in DSM cells, and their roles are largely linked to membrane depolarization and increased contractility (18, 41, 44, 52). It is important to understand how each type of ion channel contributes to DSM cell excitability and contractility in healthy and diseased states including overactive bladder (OAB), a disorder that can be often associated with increased excitability and contractility of DSM–detrusor overactivity (DO).

Despite huge progress with cationic channels made in the past few decades (44), little is known about Cl− channels in DSM cells. In vascular, cardiac, and gastrointestinal smooth muscle, Cl− channels have been identified as important regulators of contractility (for a review, see Ref. 6). Specifically, at resting membrane potentials, Cl− channel activation may generate a depolarizing current eventually leading to smooth muscle contraction (6). Variable expressions of Cl− channels in vascular smooth muscle cells have been documented, including Ca2+-dependent transmembrane protein 16A/anoctamin1 (TMEM16A/ANO1), cGMP- and Ca2+-dependent Cl− channel (cGMP-dependent ClCa), voltage-dependent Cl− channels/antiporters (CLC), cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance (CFTR), and ligand-gated glycine and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors (6, 55).

We hypothesize that Cl− channels exist in DSM cells, and regulate their excitability. Indeed, lowering extracellular Cl− transiently depolarized the DSM cell membrane potential and increased amplitudes of spontaneous phasic contractions and Ca2+ transients in trigone smooth muscle (50). The molecular identity of Cl− channels/transporters underlying the effects of Cl− substitution/reduction remains to be elucidated. So far, functional evidence for the presence of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels in pig DSM cells has been provided using pharmacological tools coupled with Cl− ion substitution in patch-clamp recordings (24). Niflumic acid or 4,4′-diisothiocyano-2,2′-stilbenedisulfonic acid (DIDS), both nonselective inhibitors of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels, reduced endothelin-1-induced current oscillations in pig DSM cells and contractions in tissue strips (24). The presence of a Cl− conductance in mouse DSM cells was suggested in extracellular Cl− replacement experiments (56). In rat DSM cells, application of niflumic acid resulted in a decrease in voltage-sensitive dye fluorescence, suggesting hyperpolarization (30). This effect was further exaggerated in DSM cells obtained from obstructed urinary bladders (partial bladder outlet obstruction, or pBOO, model) (30). Authors related the inhibitory effect of niflumic acid to the presence of a CLCA gene transcript in DSM cells (30). However, it is now recognized that CLCA gene products are not integral membrane proteins of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels, but they instead are secreted interacting signaling molecules (17, 43, 51). The preliminary evidence collectively suggests the existence of Cl− channels in DSM cells. The direct detection and detailed biophysical characterization of Cl− channels in DSM would be the first step toward enhancing our understanding of the role(s) of Cl− channels in DSM cells under normal and diseased conditions including OAB/DO.

Here we directly show, for the first time, the presence of Ca2+-insensitive voltage-dependent Cl− channels in DSM cells using inside-out single-channel patch-clamp and whole cell voltage-clamp recordings. Based on its voltage-dependent gating, this channel may be a critical regulator of DSM excitability.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical approval.

Hartley guinea pigs (Charles River Laboratories) were housed at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC), and all experiments were carried out in accordance with procedures reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at UTHSC (protocol no. 17-075.0). Guinea pigs were euthanized by a regulated overdose delivery of compressed CO2 or isoflurane followed by thoracotomy.

DSM cell isolation.

DSM tissues (mucosa-free) were obtained from adult male guinea pigs weighing 370–1,159 g (median 908 g, 25th percentile 587 g, and 75th percentile 993 g, N = 30) by following procedures described earlier (48). Guinea pig DSM cells were freshly isolated utilizing a two-step enzymatic digestion with papain and collagenase type II as described earlier (2, 20, 42). Nominally Ca2+-free dissection solution (DS) containing (in mM) 80 monosodium glutamate, 55 NaCl, 6 KCl, 10 glucose, 10 2-[4-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl]ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 2 MgCl2, and at pH 7.3 adjusted with NaOH was used as base solution during all stages of DSM cell isolation. Strips of DSM tissues, 2–5 mm long and 1–2 mm wide, were placed into a 3–5 ml plastic tube containing 1–2 ml of DS supplemented with 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 1 mg/ml dithiothreitol, and 1.5 mg/ml papain (Worthington Biochemical, Lakewood, NJ), and incubated for 17–35 min at ~37°C. After the incubation, DSM strips were washed briefly in 1–2 ml of chilled DS followed by 17–35 min of incubation in DS supplemented with 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 100–200 µM CaCl2, and 2 mg/ml collagenase type II (Sigma-Millipore, St. Louis, MO) at ~37°C. DSM strips were then washed gently several times in 1–2 ml of chilled DS and triturated with a fire-polished Pasteur pipette until single DSM cells were obtained.

Electrophysiology.

Single-channel activity was recorded from inside-out excised plasma membrane patches of DSM cells obtained from 11 male guinea pigs. Patch pipettes were fabricated from borosilicate glass with a trough filament (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) and were filled with a pipette recording solution consisting of (in mM) 110 NaCl, 1.5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 60 mannitol, 10 HEPES, 0.001 paxilline, and 0.01 nifedipine, at pH 7.4. The bath solution contained (in mM) 110 Na-Glutamate, 5 NaCl, 60 mannitol, 10 HEPES, 1 CaCl2, 1 CoCl2, and 0.5 phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), at pH 7.2. For Ca2+-free bath solution, we removed all divalent cations and added 5 mM ethylene glycol-bis(2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) instead. Both pipette and bath solutions were modified from the method described in Ref. 16 to detect single-channel activities of Cl− and cation channels. Such detection and separation were possible based on calculated equilibrium potential differences for Cl− (ECl = −65 mV) and Na+ (ENa = −1 mV) ions.

For whole cell patch-clamp recordings, data were collected from DSM cells with average capacitance 43.6 ± 1.3 pF (n = 81, N = 28 animals). The impact of series resistance (corrective) and whole cell capacitance (predictive) on the whole cell voltage clamp was compensated by at least 80% with circuitry of the Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). DSM cells were voltage-clamped at −100 mV. Leak-subtracted recordings were obtained by employing the P/N method with a number of subsweeps N = 8 and N = 6 for 100 ms and 1 s voltage steps, respectively, and opposite to the stimulation waveform polarity (4). In some experiments, a 3 M KCl-filled agar bridge for the indifferent electrode was used to minimize the effect of junction potential alteration when changing bath solutions. Bath and pipette solution combinations used for the various experimental conditions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Bath and pipette solution composition for whole cell patch-clamp recordings

| Bath/Pipette Solution Type | Bath Solution, mM | Pipette Solution, mM | Junction Potential, mV |

|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl/Na-Glu | 110 NaCl, 1.5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1 GdCl3, 60 mannitol, 10 HEPES, 0.001 paxilline, 0.01 nifedipine, pH 7.4 | 110 Na-Glutamate, 5 NaCl, 60 mannitol, 10 HEPES, 1 CaCl2, 1 CoCl2, pH 7.2 | 13.2 |

| TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate | 150 TEA-Cl, 1.5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1 GdCl3, 10 HEPES, 0.001 paxilline, 0.01 nifedipine,pH 7.4 | 150 TEA-methanesulfonate, 1 CaCl2, 1 CoCl2, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 | 7.3 |

| TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-high-Ca2+ | 150 TEA-Cl, 1.5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1 GdCl3, 10 HEPES, 0.001 paxilline, 0.01 nifedipine, pH 7.4 | 150 TEA-methanesulfonate, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 | 7.6 |

| TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-zero Ca | 150 TEA-Cl, 1.5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1 GdCl3, 10 HEPES, 0.001 paxilline, 0.01 nifedipine, pH 7.4 | 150 TEA-methanesulfonate, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 | 7.5 |

| TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-physiological-Ca2+ | 150 TEA-Cl, 1.5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1 GdCl3, 10 HEPES, 0.001 paxilline, 0.01 nifedipine, pH 7.4 | 150 TEA-methanesulfonate, 5 EGTA, 4.04 CaCl2 (300 nM free Ca2+), 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 | 7.5 |

| Control | 150 TEA-Cl, 1.5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1 GdCl3, 10 HEPES, 0.001 paxilline, 0.01 nifedipine, pH 7.4 | 150 TEA-methanesulfonate, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 | 7.8* |

| MsO− | 150 TEA-methanesulfonate, 1.5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1 GdCl3,10 HEPES, 0.001 paxilline, 0.01 nifedipine, pH 7.4 | 150 TEA-methanesulfonate, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 | 7.8* |

| I− | 150 TEA-I, 1.5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1 GdCl3,10 HEPES, 0.001 paxilline, 0.01 nifedipine, pH 7.4 | 150 TEA-methanesulfonate, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 | 7.8* |

| Br− | 150 TEA-Br, 1.5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 1 GdCl3, 10 HEPES, 0.001 paxilline, 0.01 nifedipine, pH 7.4 | 150 TEA-methanesulfonate, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 | 7.8* |

3 M KCl-filled agar bridge used for indifferent electrode.

Both single-channel and whole cell currents were recorded using an Axopatch 200B amplifier, filtered at 1 kHz using an inline four-pole Bessel filter, and data were digitized at 10 kHz using a DigiData 1440A interface (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA). All recordings were obtained at room temperature (21–23°C).

Offline data analyses.

All single-channel and whole cell analyses were performed using Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR), Clampfit10 (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA), or Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) software programs. Original single-channel patch-clamp recordings were filtered offline using a low-pass Bessel filter at 1 kHz. Single-channel current amplitudes were determined in Clampfit using single-channel threshold detection procedure followed by plotting current histograms and measuring the difference between two neighboring peaks of the current amplitude normal distributions, reflecting the fully closed and opened states. The single-channel current amplitude–membrane potential relationship was adjusted for the junction potential of 13.2 mV calculated in Clampex. Mean open probability (NPo) was determined by integrating the open durations over the total duration of a recording at a given membrane potential, as done previously (33). The mean open probability–membrane potential relationship was fitted with a Boltzmann equation to determine a maximum mean open probability, a voltage resulting in a half-maximum of mean open probability (V0.5), and a steepness of the voltage dependence (slope k factor). The first latency period was excluded from the calculations.

Whole cell current values were obtained by averaging step currents at the last seven milliseconds of 0.1 s and 1 s depolarizing pulses from −60 mV to +130 mV with 10 mV increments. Then, current density was calculated as a ratio of current value to the cell capacitance. Membrane potentials were adjusted by the junction potential values (Table 1) obtained in Clampex 10. For ramp protocol recordings, cells were held at −100 mV and 1 s ramps to +100 mV were delivered every 6 s with a rate of 0.2 mV/ms. We also used this protocol to evaluate the effect of Cl− channel inhibitors or anion substitution. We calculated a fraction of Cl− current inhibition as 1 – I/ICntl, where I is the current amplitude measured at +100 mV at the last time point of the inhibitor/substitute ion application and ICntl is a calculated control current amplitude that takes into a consideration a linear component of current rundown. Specifically, ICntl is the arithmetic average of the current amplitude at the time right before a drug/substitute ion application and the current amplitude at the washout time point equal to the duration of drug/ion substitute application (for example, in Fig. 9A, current amplitudes at time points a and c were averaged to obtain ICntl). The percentile of inhibition was obtained by multiplying the fraction of inhibition by 100 %.

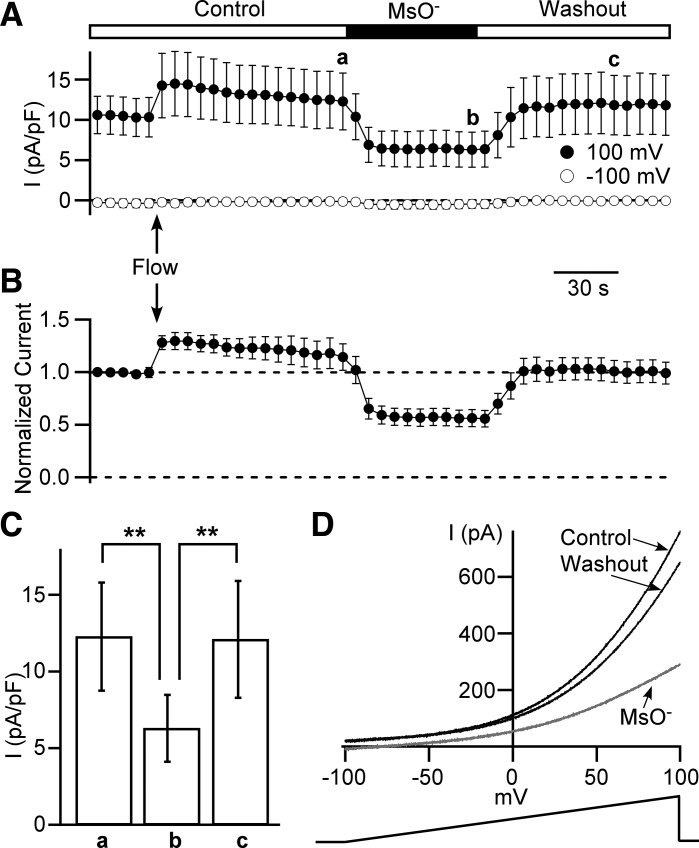

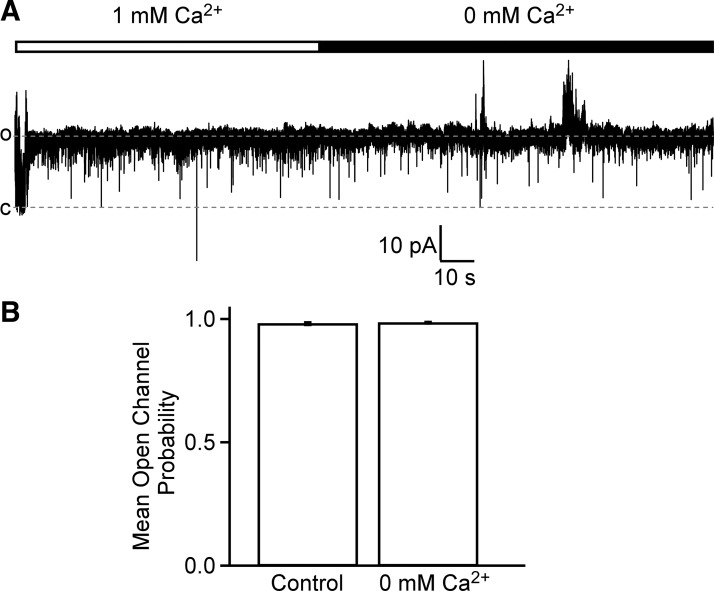

Fig. 9.

Effect of low extracellular Cl− concentrations on the outwardly rectifying whole cell current density. A and B: time courses of outward current obtained from 1 s long ramps from −100 mV to +100 mV. A: leak-unsubtracted current was measured at +100 mV (closed circles) and −100 mV (opened circles). The time course recording starts in a control (Control) extracellular solution. After the fifth ramp, local perfusion is switched on (marked as “Flow” and arrow) and remains to the end of the recording. After 20th ramp, cells are perfused with a low Cl− concentration solution containing 150 mM methanesulfonate anions (MsO−) and 10 mM Cl− for the next 10 ramps followed by a washout with Control bath solution (see materials and methods). Data points for +100 mV group marked as a, b, and c are used for statistical analysis (see C) (n = 11, N = 3). B: time course of outward current at +100 mV normalized to the first ramp value. C: data group for 10 mM Cl− (time point b in A) is significantly lower (**P < 0.01, two-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni posttest correction) from both the control (time point a in A) and washout (time point c in A). D: examples of currents evoked by ramps at time points a (Control, black line), b (methanesulfonate - MsO− light gray line), and c (Washout, dark gray line). The duration of the ramp is 1 s, and the rate of membrane potential increase is 0.2 mV/ms.

Statistical analyses.

Data were calculated and presented as mean ± SE (normal/Gaussian distribution) or median (25th and 75th percentiles) (non-Gaussian distribution). Normality testing was carried out using GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA). Student’s paired t-test was used for within-cell comparisons. Student’s t-test (paired or unpaired) or ANOVA [one-way with Tukey’s honest significant difference (HSD) post hoc test or two-way with a Bonferroni posttest correction] analysis was used to test for differences among two and three groups, respectively. Statistical determinations were made using GraphPad Prism software version 4, Igor Pro 8, or Microsoft Excel 2016. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant; n describes the number of cells (whole cell) or patches (inside-out) recorded from, and N represents the number of male guinea pigs used. Statistical determinants were made on n values.

Chemicals.

Papain was obtained from Worthington Biochemical. Paxilline and chlorotoxin were purchased from the Alomone Labs (Jerusalem, Israel). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Millipore. Stock solutions for nifedipine (10 mM), paxilline (1 mM), and niflumic acid (100 mM) were prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma-Millipore). Stock solution for chlorotoxin (300 µM) was prepared in type I purified water.

RESULTS

Characterization of Cl− single-channel activity in excised patches derived from freshly isolated DSM cells.

To our knowledge, there are no prior reports of Cl− single-channel activity in DSM cells. Here, we used both bath and pipette solutions, which allowed us to separate Cl− conductance from cation conductance in DSM cell membrane-excised patches (see materials and methods for composition of single-channel solutions). We have detected several characteristic patterns of single-channel activities, suggesting a presence of multiple ion channel types in DSM cells. Many of them were Na+-conducting channels with reversal potential close to the calculated value of −1 mV. Eight percent of patches (16 out of 201 patches, N = 11) demonstrated a robust voltage-dependent single-channel activity that occurred at potentials higher than −53.5 mV (Fig. 1, A and B). This channel showed a linear single-channel current amplitude–membrane potential relationship with the unitary conductance of 164 ± 4 pS and reversal potential −41.5 ± 1.3 mV (n = 15, N = 11, Fig. 1B). Given the fact that calculated ECl at our experimental conditions was −65 mV, and that Na+-conducting channels should change current direction around −1 mV, we conclude that this channel was primarily permeable to Cl−. Importantly, this was the only type of Cl− single-channel conductance detected under the experimental conditions applied in this study.

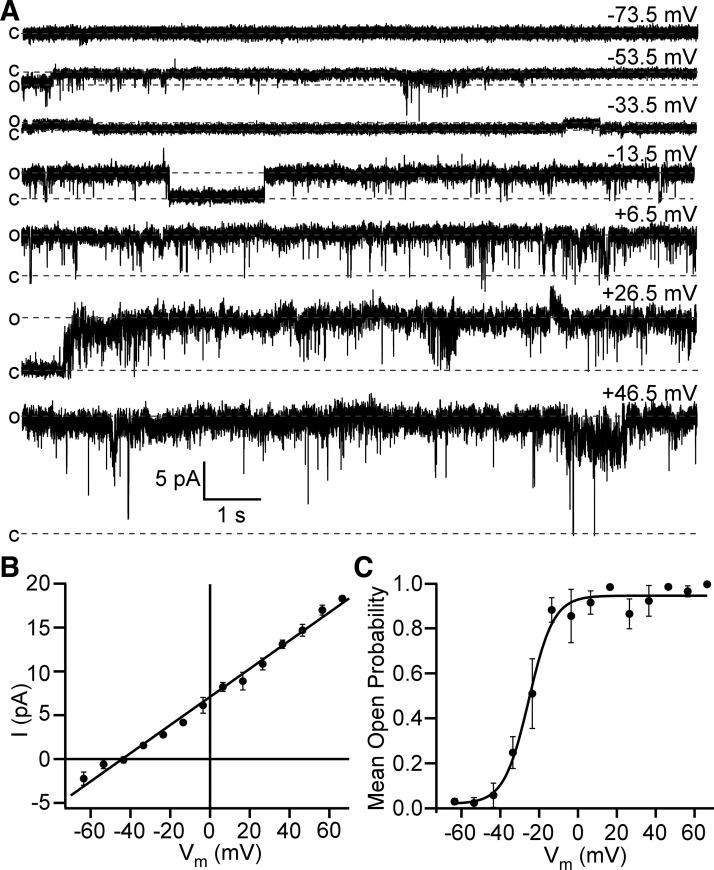

Fig. 1.

Detrusor smooth muscle (DSM)-excised membrane patches display a high-conductance and voltage-dependent Cl− single-channel activity. A: representative traces of single-channel activity recorded at different voltages in the same inside-out patch. Closed (c) and opened (o) states are shown as dotted lines. Holding potential for each trace is shown in the top right corner. The scale bars for current and time apply to all traces shown. B: shown is the linear function fitting of the single-channel amplitude (I)–membrane potential (Vm) relationship yielding single-channel conductance = 161 pS and reversal potential = −44.2 mV that is close to Cl− equilibrium potential (ECl) = −65 mV; n = 3–14. C: mean open probability (NPo)–membrane potential relationship for data fitted with Boltzmann equation yielded: maximum mean open probability = 0.95, half-maximum of mean open probability (V0.5) = −22.3 ± 4.9 mV, and slope k factor 4.2 ± 1.7 mV (n = 9, N = 6).

It should be noted that Cl− channel activity did not occur instantaneously after the patch excision. Even at higher depolarizing potentials above −13.5 mV, it could take a few seconds or longer, up to 5 min, before single Cl− channel openings occurred. Therefore, we excluded the first latency period from the mean open probability calculations. Once the channel opening occurred, it lasted for several minutes without a visible decline. We found that the Cl− channel had a steep voltage dependence of mean open probability (Fig. 1 C). The channel remained always closed at potentials below −53.5 mV but maximally and almost always opened at potentials higher than −13.5 mV. Boltzmann fitting of mean open probability versus membrane potential yielded the following parameters: maximum mean open probability = 0.95 ± 0.2, a V0.5 =−22.3 ± 4.9 mV, and slope k factor = 4.2 ± 1.7 mV (n = 9, N = 6, Fig. 1 C). Thus, given the dynamic membrane potential range of activation, we concluded that this Cl− channel can be activated at physiological conditions, and that it contributes to controlling the membrane potential, especially near the values of the plateau phase of the action potential.

We also found that the Cl− channel displays subconductive levels, which were more apparent at higher depolarizing membrane potentials (Fig. 2). This was not surprising because several types of Cl− channels express subconductive levels (3, 32, 35, 54, 57).

Fig. 2.

Detrusor smooth muscle (DSM) Cl− single-channel activity shows subconductive levels at higher depolarizing potentials. A: a representative trace showing two subconductive levels s1 and s2 (intermediate dotted lines) obtained at a holding potential of +26.5 mV. Top and bottom dotted lines represent opened (o) and closed (c) states. B: a typical trace of Cl− single-channel activity at +46.5 mV illustrates substantial dwelling of the channel at subconductive levels s1 and s2 at higher depolarizing potentials. Traces in A and B were recorded from the same excised patch.

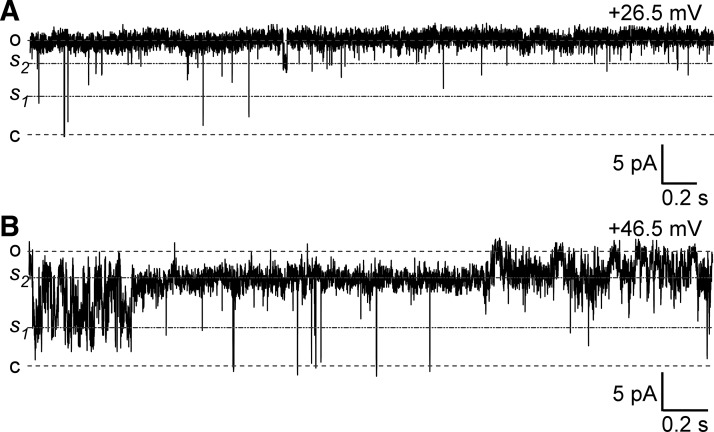

Cytoplasmic Ca2+ is not necessary for Cl− single-channel activity in freshly isolated DSM cells.

Several reports have documented the presence of Ca2+-sensitive TMEM16A/ANO1 Cl−-conducting channel in vascular smooth muscle cells (9, 34, 55). Although the unitary conductance of the Cl− channel in DSM cells observed in this study is much higher than for the TMEM16A channel (47, 60), we hypothesized that the high-conductance DSM Cl− channel may be regulated by cytoplasmic Ca2+. Our experimental data showed that replacement of 1 mM Ca2+ in the bath solution with 0 mM Ca2+ solution (with 5 mM EGTA) did not reduce Cl− single-channel NPo activity (P > 0.05, n = 5, N = 4, Fig. 3). Thus, the DSM Cl− channel is not regulated by cytoplasmic Ca2+.

Fig. 3.

Detrusor smooth muscle (DSM) Cl− single-channel activity did not change when intracellular Ca2+ concentration was reduced from 1 mM to 0 mM. A: a representative trace showing no effect of 0 mM Ca2+ cytoplasmic (bath) solution application on Cl− channel activity. Holding potential = +76.5 mV. B: mean single-channel open probability was not significantly different between control (1 mM Ca2+) and 0 mM Ca2+ groups (P > 0.05, n = 5, N = 4, paired Student’s t-test).

Outwardly rectifying whole cell current is likely caused by Cl− channel activation.

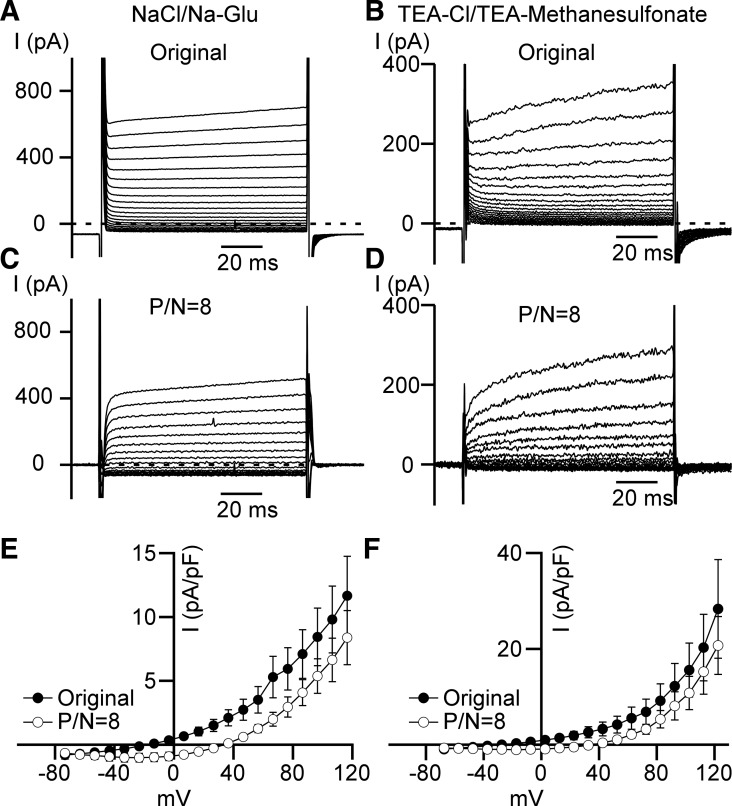

Our excised inside-out single-channel patch-clamp data point out clearly that Cl− channels in DSM cells should be able to generate a substantial macroscopic current upon membrane depolarization in whole cell patch-clamp recordings. To optimally detect the whole cell Cl− current in DSM cells, we used solutions similar to those described above for single-channel patch-clamp recording conditions (see Table 1). The presence of 1 mM GdCl3 in the bath solution ensured inhibition of cationic channels, including TRP, voltage-gated Ca2+, and store-operated calcium entry (SOCE) channels (5, 8, 38) (see Table 1, NaCl/Na-Glu bath and pipette solutions). Under these experimental conditions, we observed an outwardly rectifying whole cell current caused by 100 ms depolarizations from the junction potential-adjusted holding potential of −113.2 mV to the membrane potentials, in a range from −73.3 mV to 116.5 mV in 10 mV steps (Fig. 4, A, C, and E). We observed this current in every cell examined with NaCl/Na-Glu solutions employed (n = 6, N = 2). This outward current rectification persisted when recordings were corrected by employing an online linear leak current subtraction P/N = 8 method (see materials and methods). A small inward current observed for leak-subtracted currents could be caused by the presence of a small nonlinear component of the current even at voltages near and below holding potentials (Fig. 4, C and D).

Fig. 4.

Outwardly rectifying whole cell current does not depend on Na+ conductance. A and B: representative recordings of leak-unsubtracted (Original) whole cell step currents. NaCl/Na-Glu (A) and TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate (B) denote bath and pipette solutions used for these experiments (see materials and methods). C and D: examples of leak-subtracted (P/N = 8) traces obtained at NaCl/Na-Glu (C) and TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate (D) conditions. E: whole cell current density–membrane potential relationships obtained for NaCl/Na-Glu recording conditions (original and leak-subtracted). Currents were generated by depolarizing 100 ms voltage steps with 10 mV increments (n = 6, N = 2). Closed circles refer to leak-unsubtracted (Original) recordings, and open circles refer to leak-subtracted (P/N = 8) recordings. F: whole cell current density–membrane potential relationships obtained at TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate conditions. Currents were generated by depolarizing 100 ms voltage steps with 10 mV increments (n = 6, N = 2).

We observed the same outwardly rectifying whole cell currents after replacing Na+ in both bath and pipette solutions with tetraethylammonium (TEA) and glutamate with methanesulfonate in the pipette solution (n = 6, N = 2, TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate solutions; see Table 1; Fig. 4, B, D, and F). The outwardly rectifying current was prominent at very high depolarizing potentials (> +40 mV), and the full current activation required depolarizing steps longer than 100 ms (Fig. 4). These experiments confirmed that the outwardly rectifying current observed was not due to Na+, K+, or Ca2+ conducting channels, but rather to Cl− permeable channels.

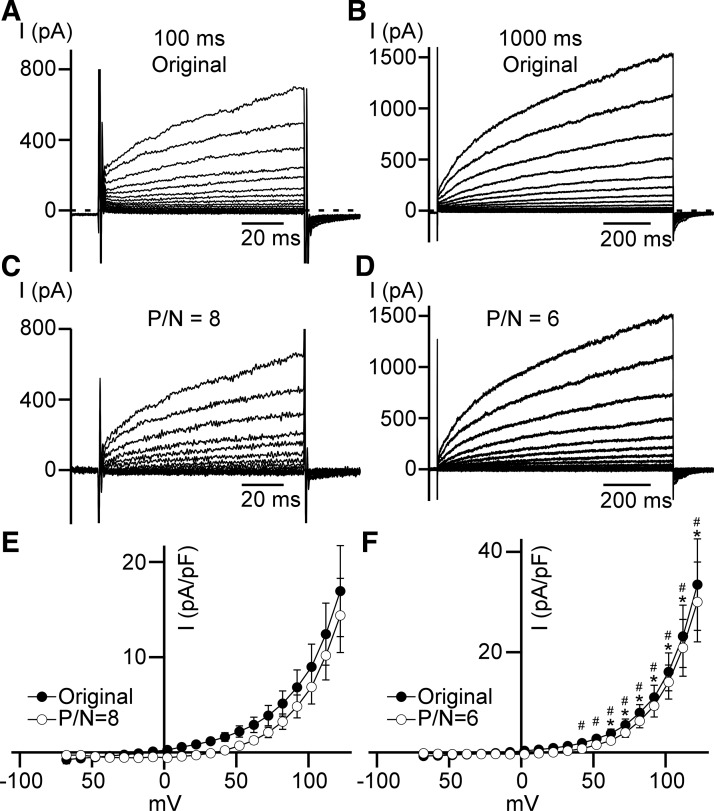

DSM whole cell currents show calcium-independent outward rectification but high calcium-dependent activation kinetics.

To investigate the effect of high cytosolic Ca2+ concentration as the only divalent cation in cytoplasm on outward current, we removed Co2+ from the pipette solution but kept the same bath solution (TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-high-Ca2+ conditions; see Table 1). As expected, the outwardly rectifying whole cell current occurred in the same voltage range of depolarizing steps (Fig. 5). However, an increase in the duration of depolarizations from 100 ms to 1 s resulted in a statistically significant larger outward current at potentials higher than 52 mV for the leak-unsubtracted original currents (n = 7, N = 2, P < 0.05) or at potentials higher than 22 mV for leak-subtracted currents (n = 7, N = 2, P < 0.05) (Fig. 5F). Such an increase in the current could be explained by a slow activation component that may require up to several seconds to achieve its maximum (Fig. 5, B and D).

Fig. 5.

Sensitivity of outwardly rectifying whole cell current to the high cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration. A and B: typical leak-unsubtracted (Original) currents of 100 ms (A) and 1,000 ms (B) duration recorded at TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-high-Ca2+ conditions (see materials and methods). C and D: representative leak-subtracted [P/N = 8 (C) and P/N = 6 (D)] currents of 100 ms (C) and 1,000 ms (D) intervals. E and F: whole cell current density–membrane potential relationships obtained during 100 ms (E) and 1,000 ms (F) depolarizing steps from −100 mV (n = 7, N = 2). Closed and opened circles are leak-unsubtracted (Original) and leak-subtracted (P/N = 8 and P/N = 6), respectively. *Significant difference (P < 0.05, n = 7, N = 2, unpaired Student’s t-test) between leak-unsubtracted 100 ms (E, closed circles) and 1,000 ms (F, closed circles) long step currents for each voltage indicated. #Significant difference (P < 0.05, n = 7, N = 2, unpaired Student’s t-test) between leak-subtracted 100 ms (E, open circles) and 1,000 ms (F, open circles) long step currents for indicated voltages.

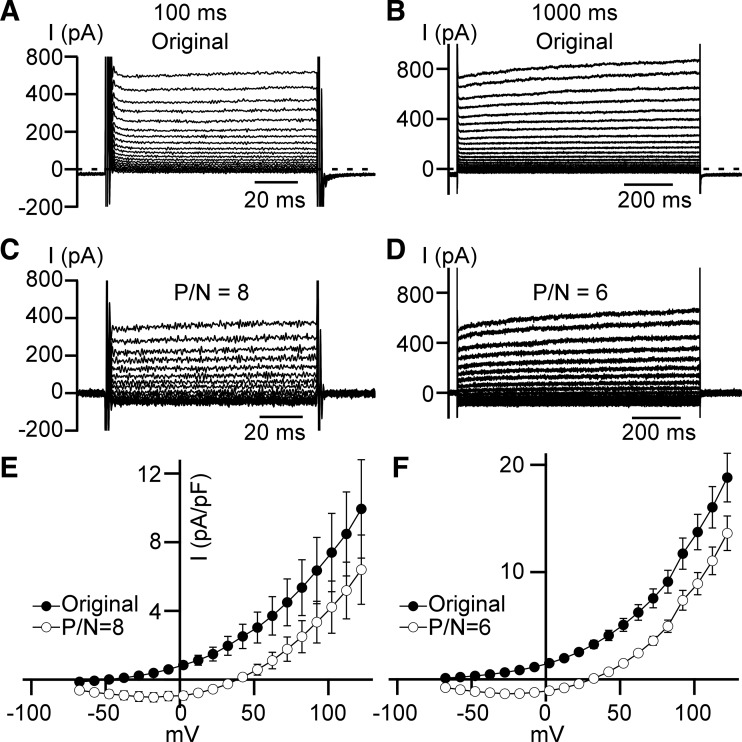

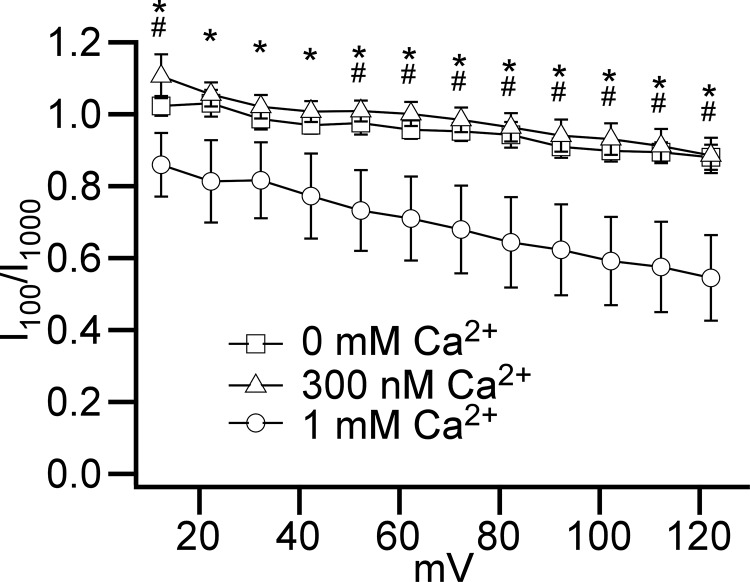

The whole cell outwardly rectifying current remained when Ca2+ was removed from the pipette solution (TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-zero Ca2+ conditions; see Table 1; Fig. 6) or at physiological (300 nM) Ca2+ concentration (TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-physiological-Ca2+ conditions; see Table 1; Fig. 7). However, the activation of the current appeared to be much slower only in the presence of high, 1 mM, Ca2+ pipette concentration (Fig. 6, A–D and Fig. 7, A–D). To estimate the significance of the difference in current activation with zero, 300 nM, and 1 mM cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentrations, we calculated I100/I1,000 ratios for the same voltage-step currents, where I100 and I1,000 represent current amplitudes measured at 100th ms and 1,000th ms of the 1 s depolarizing steps, respectively (Fig. 8) for leak-unsubtracted recordings. The ratios for the high Ca2+ (1 mM) condition were all below 1.0 at membrane potentials higher than 12 mV, and continued decreasing with the step voltage increases (Fig. 8). This implies that the voltage step-induced currents continued to grow during the entire 1 s depolarization at all these voltages, and that full activation requires a longer time interval at higher voltages. Importantly, we found that ratios were significantly lower in the presence of high cytosolic Ca2+ than were observed with Ca2+-free conditions at membrane potentials equal or higher than 52 mV or in the presence of physiological 300 nM Ca2+ concentration at voltages more positive than 12 mV (Fig. 8). Thus, outwardly rectifying current activation kinetics were slower in the presence of the high cytosolic Ca2+ concentration only. Intracellular Ca2+ concentration increase from zero to physiological level (300 nM) did not alter the activation kinetics of the voltage-step current.

Fig. 6.

The 0 mM cytosolic Ca2+ concentration does not affect outward rectification of whole cell current. A and B: typical leak-unsubtracted (Original) currents of 100 ms (A) and 1,000 ms (B) duration at TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-zero Ca2+ conditions (see materials and methods). C and D: representative leak-subtracted [P/N = 8 (C) and P/N = 6 (D)] currents of 100 ms (C) and 1,000 ms (D) duration obtained at TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-zero Ca2+ conditions. E and F: whole cell current density–membrane potential relationships obtained during 100 ms (E) and 1,000 ms (F) depolarizing steps at TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-zero Ca2+ conditions; n = 13, N = 3 in E and n = 10, N = 3 in F. Closed and opened circles represent leak-unsubtracted (Original) and leak-subtracted responses (P/N = 8 and P/N = 6), respectively.

Fig. 7.

The presence of a cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration at the physiological level of 300 nM does not alter outwardly rectifying whole cell current. A and B: typical leak-unsubtracted (Original) currents of 100 ms (A) and 1,000 ms (B) duration recorded at TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-physiological-Ca2+conditions (see materials and methods). C and D: representative leak-subtracted [P/N = 8 (C) and P/N = 6 (D)] currents of 100 ms (C) and 1,000 ms (D) intervals. E and F: whole cell current density–membrane potential relationships obtained during 100 ms (E) (n = 7, N = 2) and 1,000 ms (F) (n = 8, N = 2) depolarizing steps from −100 mV. Closed and opened circles are leak-unsubtracted (Original) and leak-subtracted (P/N = 8 and P/N = 6), respectively.

Fig. 8.

The high nonphysiological cytosolic 1 mM Ca2+ concentration slows the activation kinetics of the outwardly rectifying current. Shown are the relationships between I100/I1,000 versus membrane potential in the absence (open squares; n = 10, N = 3, TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-zero Ca2+ conditions) or the presence of 1 mM (open circles, n = 7, N = 2, TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-high-Ca2+ conditions) or 300 nM (open triangles, n = 8, N = 2, TEA-Cl/TEA-methanesulfonate-physiological-Ca2+ conditions) cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration in the pipette solution. *Membrane potentials at which ratio values for 1 mM were lower than for physiological 300 nM Ca2+ groups (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA analysis with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test). #Membrane potentials at which ratio values for 1 mM were lower than for 0 mM Ca2+ groups (P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA analysis with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test).

Outwardly rectifying current is mediated by Cl−.

To further investigate if the outwardly rectifying current is indeed a Cl− current, we designed a series of experiments, which recorded time courses of currents activated by 1 s membrane potential ramps from −100 mV to +100 mV with 6 s interval between ramps (Fig. 9). This design allowed us to monitor outward rectification and to measure current amplitude at chosen voltages of −100 mV and +100 mV. All whole cell patch-clamp recordings were isochronic by design. We used control (Control) bath/pipette solution conditions at the beginning of the experiment (Table 1). After the fifth ramp, we started a perfusion with the bath solution followed by the application of MsO− solution (Table 1) after the twentieth ramp and the wash-out (Washout) back to the Control solution occurred after the thirtieth ramp (Fig. 9, A and B).

Of note, the ramps (at +100 mV) demonstrated a transient increase in the current amplitude following the initiation of the perfusion, indicating that this current might be positively modulated by a shear stress (Fig. 9, A and B). Importantly, switching to the MsO− solution containing 150 mM methanesulfonate anion (MsO−) and low (10 mM) Cl− concentrations almost immediately decreased the current amplitude by 49.7 ± 2.8 % (n = 11, N = 3, P < 0.01) but preserved the outward rectification (Fig. 9, A, B, and D). This effect was statistically significant and completely reversible (n = 11, N = 3, P < 0.01, Fig. 9C). Thus, we conclude that the outwardly rectifying current was caused by the voltage-dependent activation of Cl− channels.

Outwardly rectifying Cl− channel is less permeable for Br− and I− than for Cl−.

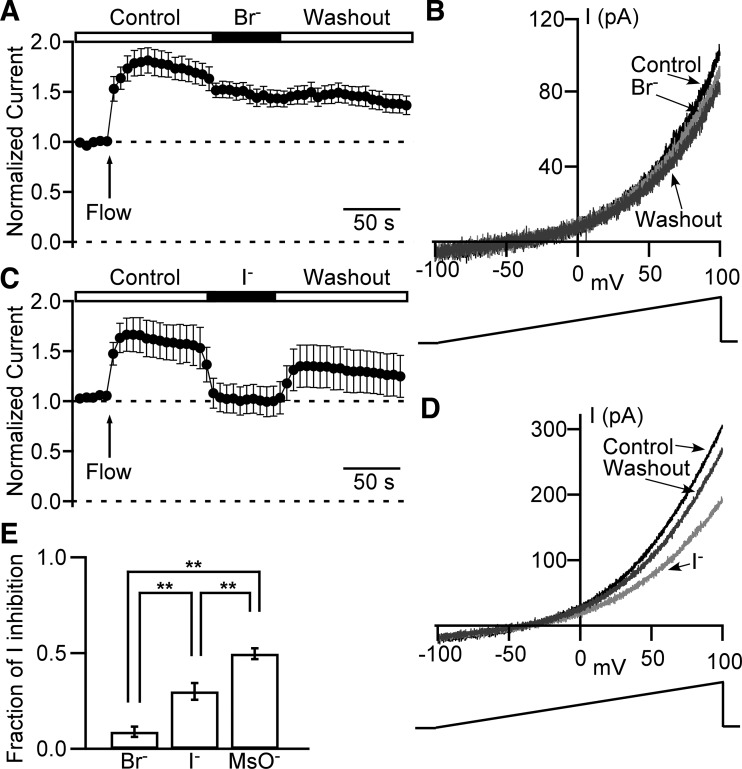

To examine selectivity and permeability properties of the DSM Cl− channel, we used an identical approach for MsO− substitution experiments described above (see also Fig. 9). Specifically, the Br− solution (Table 1) was used to substitute 150 mM Cl− with 150 mM Br− (Fig. 10, A and B). This resulted in a small but statistically significant reduction of the current by 8.9 ± 2.7 % (n = 12, N = 3, P < 0.05). Similarly, a substitution of Control solution with I− solution (Table 1) caused a current decrease of 30.0 ± 4.4 % (n = 8, N = 3, P < 0.05, Fig. 10, C and D). ANOVA analysis revealed a significant difference for the fraction of anionic current reduction among all three groups for Cl− substitution experiments: Br−, I−, and MsO− (P < 0.05, Fig. 10E). We conclude that the guinea pig DSM Cl− channel exhibits the following rank order of permeabilities: Cl−>Br−>I−>MSO−.

Fig. 10.

Cl− channels in DSM cells have permeability preference sequence: Cl−>Br−>I−>MsO−. A and C: normalized leak-unsubtracted time courses of the outward current obtained from 1 s long ramps from −100 mV to + 100 mV and measured at +100 mV. Arrows indicate time points of local perfusion starts (also marked as “Flow”). The recording starts in control extracellular solution followed by the isochronic application of Br− (n = 12, N = 3) (A) or I− (n = 8, N = 3) (C) extracellular solutions and washout. B and D: examples of currents evoked by ramps at time points of control (Control, black) right before switching to Br− (B) or I− (D), at the end of Br− (B) or I− (D) application (light gray), and same as Br− (B) or I− (D) application long duration washout (dark gray). The duration of the ramp is 1 s, and the rate of membrane potential increase is 1 mV/10 ms. E: fractional reduction of whole cell current caused by a replacement of 150 mM Cl− with 150 mM Br− (n = 12, N = 3), I− (n = 8, N = 3), or MsO− (n = 11, N = 3). **Significant difference between data groups with P < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA analysis with Tukey’s HSD post hoc test).

Niflumic acid and 4,4'-diisothiocyanostilbene-2,2'-disulfonic acid inhibit Cl− current.

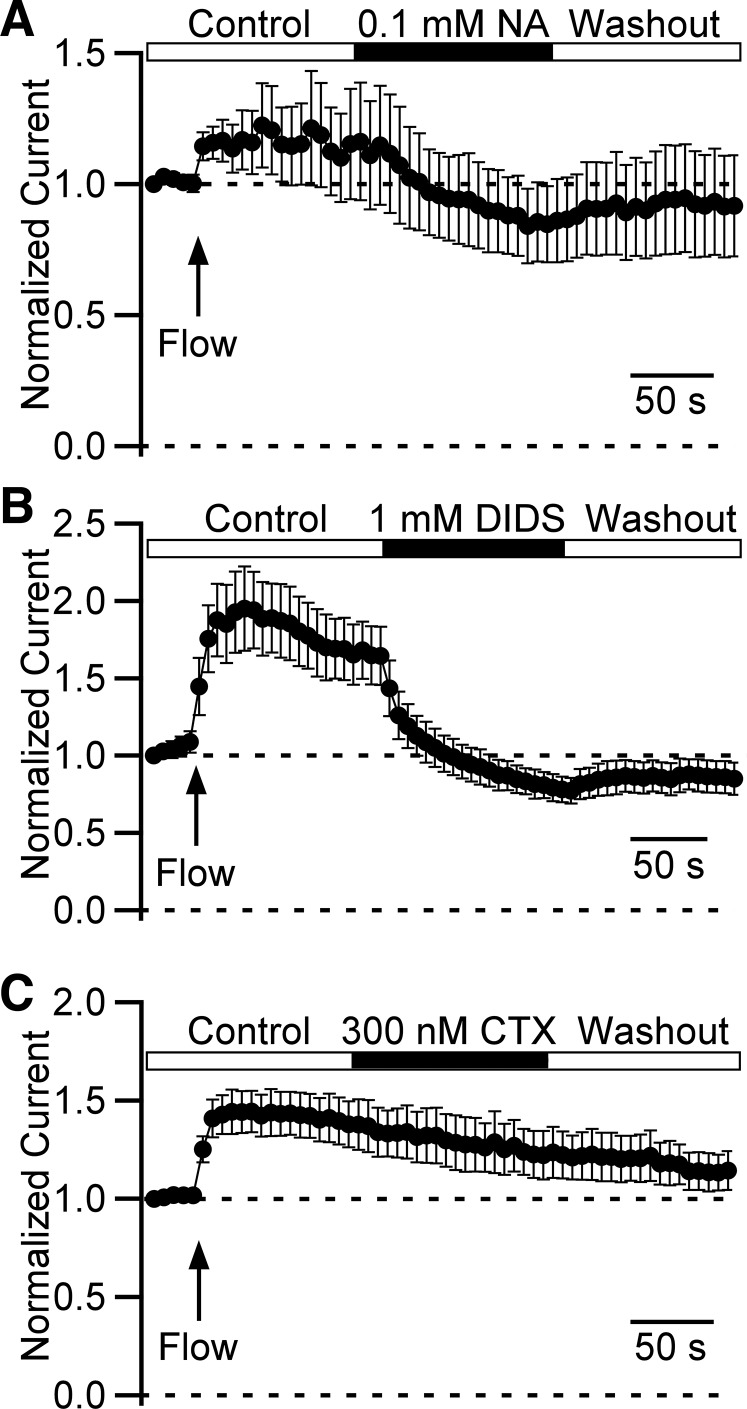

To further confirm the presence of Cl− channels in DSM cells, we tested common Cl− channel blockers: niflumic acid, DIDS, and chlorotoxin. We used the same voltage-ramp time course protocol as described previously. We found that 0.1 mM niflumic acid inhibited whole cell current reversibly by 15.6 ± 2.8 % (n = 5, N = 3, P < 0.05, Fig. 11A). Similarly, 1 mM DIDS reduced the current by 36.6 ± 4.3 % (n = 4, N = 3, P < 0.05, Fig. 11B). The inhibitory effect of DIDS and niflumic acid, however, could underestimate the overall efficacy of the compounds for inhibiting the currents due to rundown during this series of experiments and incomplete recovery upon the compound removal. As we expected, 300 nM chlorotoxin, a small-conductance chloride channel inhibitor (11, 12), did not affect the currents (n = 5, N = 3, P > 0.05, Fig. 11C).

Fig. 11.

Niflumic acid and DIDS inhibit outwardly rectifying Cl− current in detrusor smooth muscle (DSM) cells while chlorotoxin does not. A–C: normalized leak-unsubtracted time courses of Cl− currents measured at +100 mV caused by repetitive 1 s voltage ramps from −100 mM to +100 mV. Data were normalized to the first data point value. Arrow indicates the beginning of local perfusion (also marked as “Flow”). Isochronic drug applications show inhibitory effects of niflumic acid (NA, n = 5, N = 3) (A) and DIDS (n = 4, N = 3) (B), and no effect of chlorotoxin (CTX, n = 5, N = 3) (C) on Cl− current.

Collectively, both our single-channel and whole cell patch-clamp findings strongly support the presence of voltage-dependent, niflumic acid- and DIDS-sensitive, and Ca2+-independent Cl− channels in DSM cells.

DISCUSSION

This study used both single-channel and whole cell patch-clamp techniques to detect and characterize Cl− channel activity in the plasma membrane of freshly isolated DSM cells. The experimental data showed a previously unrecognized Ca2+-insensitive and voltage-dependent Cl− channel sensitive to niflumic acid and DIDS that may be an important regulator of membrane excitability in DSM cells.

We found that the Cl− channel detection rate was relatively low in single-channel patch-clamp recordings. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that some fraction of these channels could be silent during the entire recordings. This idea is supported by the observation that it could take up to several minutes before we detected Cl− single-channel activity even at high depolarizing potentials. Thus, we propose that the 8% detection rate reported here serves as the lowest estimate of Cl− channel expression. Assuming that membrane patch area was ~1–2 µm2 and 8% detection rate, we should expect the lowest estimated Cl− channel density in a range of 1 channel per 12.5–25 µm2 of membrane surface that would result in 320–640 channels per single DSM cell of average capacitance (40 pF). Such expression level coupled with high unitary conductance of 164 pS would be sufficient to generate a substantial Cl− current upon activation, having a pronounced effect on DSM cell excitability. During our single-channel recordings, we never observed more than one active DSM Cl− channel and only a single type of Cl− conductance. Thus, we do not anticipate that Cl− channels form clusters in the plasma membrane of DSM cells.

Our single-channel activity recordings showed a steep voltage dependence for mean open probability (Fig. 1F). At the whole cell level, outwardly rectifying currents displayed robust voltage dependence (Figs. 3–8). Thus, our whole cell data are in good agreement with the single-channel patch-clamp recordings. We cannot rule out the possibility that the whole cell Cl− current could be due to additional Cl− channel components not observed in inside-out patches.

In the whole cell experiments, we found that the Cl− current fully activated with slower kinetics in the presence of high cytosolic Ca2+ concentration than was observed at physiological intracellular Ca2+ level or in the absence of Ca2+ (Fig. 8). This observation suggests limited, if any, contribution of Ca2+-activated Cl channels to the total Cl− conductance at physiological conditions. Indeed, outward rectification and current densities were similar for cells measured in the absence and presence of physiological or high cytosolic Ca2+ (compare Figs. 5, 6, and 7). Our single-channel recordings showed that once the channel becomes open, cytosolic Ca2+ removal does not affect its gating. One explanation could be that slower Ca2+-dependent activation may be caused by reduced rate(s) of closed-closed state transition(s) in the presence of high nonphysiological cytosolic Ca2+ concentration. Based on our whole cell and inside-out single-channel patch-clamp results, it is unlikely that DSM cells expressed Ca2+-activated Cl− channels at sufficient level to generate a detectable Ca2+-dependent current component at physiological conditions (24).

The molecular identity of DSM chloride channels remains to be determined. A group of voltage-dependent Cl− channels/antiporters encoded by the nine-member ClCn gene family might be suitable candidates. While ClC-1, ClC-2, ClC-Ka, and ClC-Kb channels are not likely candidates based on their voltage activation profile and unitary conductance (1, 22, 39, 49, 61), ClC-3, ClC-4, ClC-5, ClC-6, and ClC-7 antiporters are characterized by strong voltage dependence and outward rectification (7, 19, 28, 36, 46). Depending on a type, each of them has a unique permeability sequence. We detected the permeability sequence Cl−>Br−>I−>MsO− for the guinea pig DSM Cl− channel reported here. It is similar to the sequence reported earlier for ClC-5 (53), but it differs from ClC-3, ClC-4, and ClC-6 (7, 25, 26). To our knowledge, permeability sequence for ClC-7 has not yet been established. Hence, ClC-5 or ClC-7 may underlie DSM Cl− currents.

While ClC channels/antiporters have similar structures, their sensitivities to Cl− channel blockers vary tremendously. For example, DIDS blocks ClC-7 (28) similar to our observations here for guinea pig DSM cells, whereas this compound shows no inhibition on ClC-5 (53). The effect of DIDS on the ClC-3 channel is controversial. Some reports state that this compound does not have any effect on ClC-3 (31), while others identified inhibition (13, 15, 59). We observed a weak inhibition of Cl− current by niflumic acid consistent with ClC channels/antiporters displaying weak or no blockade to this compound (13, 21). We found that chlorotoxin did not block whole cell current, as expected for ClC channels/antiporters. Based on data reported here and published data, we suggest that candidates for the molecular identity of Cl− channel in the guinea pig DSM can be limited to ClC-5 (voltage dependence, outward rectification, permeability sequence) or ClC-7 (voltage dependence, outward rectification, sensitivity to DIDS). Insensitivity to DIDS argues against the exclusive involvement of ClC-5 in mediating Cl− currents in DSM cells. On the other hand, the blockade of currents with DIDS supports a potential role for ClC-7. It is also possible that we recorded whole cell currents from two or more types of ClC channels/antiporters, which complicates data interpretation regarding molecular, biophysical, and pharmacological properties. Thus, we need to rely on additional identifiers. One of them can be ClC sensitivity to intra- and extracellular pH change. It is known that acidic extracellular solution inhibits ClC-3 current at pH 6.0 and pH 6.3 but greatly increases ClC-3 current at pH values lower than 5.5 (36, 37). Also, acidic extracellular solution inhibits ClC-4 (40) and ClC-5 (10) currents but increases ClC-7 current (14).

It should be noted that ClC antiporters are mainly expressed in endosomes and lysosomes (for a review see Ref. 23). ClC-3, however, is being considered as a volume-sensitive Cl− channel that can also be expressed in plasma membrane of vascular smooth muscle cells (for a review see Ref. 6). Thus, it remains unknown whether either of these channels could be present in the plasma membrane of DSM cells. Therefore, more detailed biophysical, pharmacological, and immunocytochemical examinations of these candidates in guinea pig DSM are warranted. While initially considering CLC channels/antiporters as candidates for DSM Cl− channels based on the current voltage dependence and the outward rectification, other anionic channels will also need to be evaluated in the future. These include Cl− channels already detected in organelles (35). Thus, it might be possible that our list of candidates is far from complete at this moment.

It is likely that resting membrane potential in DSM cells is significantly more negative than equilibrium potential for Cl−, similar to vascular smooth muscle cells (for a review see Ref. 6). Therefore, if these channels become open at resting membrane potentials or just below Cl− equilibrium potential, they would generate an inward depolarizing current leading to increased DSM excitability. Indeed, reduction in extracellular Cl− concentration led to depolarization and increase in action potential frequency in guinea pig DSM (27). The spontaneous contractility and Ca2+ transients in urinary bladder trigone increased in low Cl− extracellular solution (50). However, based on the voltage dependence of Cl− current activation observed under our experimental conditions, we predict that Cl− current in DSM cells might occur at membrane depolarizations above the Cl− equilibrium potential, resulting in outward hyperpolarizing current limiting membrane excitability.

In conclusion, our study shows for the first time the presence of a Ca2+-independent DIDS and niflumic acid-sensitive, voltage-dependent Cl− channel in the plasma membrane of DSM cells. This channel may be a critical regulator of DSM cells.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant R01 DK-106964 awarded to G. V. Petkov.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

V.Y., J.M., and G.V.P. conceived and designed research; V.Y. performed experiments; V.Y. analyzed data; V.Y., J.M., and G.V.P. interpreted results of experiments; V.Y. prepared figures; V.Y., J.M., and G.V.P. drafted manuscript; V.Y., J.M., and G.V.P. edited and revised manuscript; V.Y., J.M., and G.V.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sarah Maxwell for critical evaluation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Accardi A, Pusch M. Fast and slow gating relaxations in the muscle chloride channel CLC-1. J Gen Physiol 116: 433–444, 2000. doi: 10.1085/jgp.116.3.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afeli SA, Hristov KL, Petkov GV. Do β3-adrenergic receptors play a role in guinea pig detrusor smooth muscle excitability and contractility? Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 302: F251–F263, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00378.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alton EW, Manning SD, Schlatter PJ, Geddes DM, Williams AJ. Characterization of a Ca(2+)-dependent anion channel from sheep tracheal epithelium incorporated into planar bilayers. J Physiol 443: 137–159, 1991. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bezanilla F, Armstrong CM. Inactivation of the sodium channel. I. Sodium current experiments. J Gen Physiol 70: 549–566, 1977. doi: 10.1085/jgp.70.5.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boland LM, Brown TA, Dingledine R. Gadolinium block of calcium channels: influence of bicarbonate. Brain Res 563: 142–150, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)91527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulley S, Jaggar JH. Cl− channels in smooth muscle cells. Pflugers Arch 466: 861–872, 2014. [Erratum in Pflügers Arch 466: 873, 2014.] 10.1007/s00424-013-1357-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buyse G, Voets T, Tytgat J, De Greef C, Droogmans G, Nilius B, Eggermont J. Expression of human pICln and ClC-6 in Xenopus oocytes induces an identical endogenous chloride conductance. J Biol Chem 272: 3615–3621, 1997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.6.3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clapham DE. SnapShot: mammalian TRP channels. Cell 129: 220.e.1, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis AJ, Forrest AS, Jepps TA, Valencik ML, Wiwchar M, Singer CA, Sones WR, Greenwood IA, Leblanc N. Expression profile and protein translation of TMEM16A in murine smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C948–C959, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00018.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Stefano S, Pusch M, Zifarelli G. A single point mutation reveals gating of the human ClC-5 Cl−/H+ antiporter. J Physiol 591: 5879–5893, 2013. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.260240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeBin JA, Maggio JE, Strichartz GR. Purification and characterization of chlorotoxin, a chloride channel ligand from the venom of the scorpion. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 264: C361–C369, 1993. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.2.C361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeBin JA, Strichartz GR. Chloride channel inhibition by the venom of the scorpion Leiurus quinquestriatus. Toxicon 29: 1403–1408, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(91)90128-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dick GM, Bradley KK, Horowitz B, Hume JR, Sanders KM. Functional and molecular identification of a novel chloride conductance in canine colonic smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 275: C940–C950, 1998. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.4.C940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diewald L, Rupp J, Dreger M, Hucho F, Gillen C, Nawrath H. Activation by acidic pH of CLC-7 expressed in oocytes from Xenopus laevis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 291: 421–424, 2002. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2002.6462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duan D, Winter C, Cowley S, Hume JR, Horowitz B. Molecular identification of a volume-regulated chloride channel. Nature 390: 417–421, 1997. doi: 10.1038/37151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Earley S, Waldron BJ, Brayden JE. Critical role for transient receptor potential channel TRPM4 in myogenic constriction of cerebral arteries. Circ Res 95: 922–929, 2004. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147311.54833.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson A, Lewis AP, Affleck K, Aitken AJ, Meldrum E, Thompson N. hCLCA1 and mCLCA3 are secreted non-integral membrane proteins and therefore are not ion channels. J Biol Chem 280: 27205–27212, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504654200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin CS, Bradley E, Dudem S, Hollywood MA, McHale NG, Thornbury KD, Sergeant GP. Muscarinic receptor induced contractions of the detrusor are mediated by activation of TRPC4 channels. J Urol 196: 1796–1808, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.05.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hebeisen S, Heidtmann H, Cosmelli D, Gonzalez C, Poser B, Latorre R, Alvarez O, Fahlke C. Anion permeation in human ClC-4 channels. Biophys J 84: 2306–2318, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75036-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hristov KL, Chen M, Soder RP, Parajuli SP, Cheng Q, Kellett WF, Petkov GV. KV2.1 and electrically silent KV channel subunits control excitability and contractility of guinea pig detrusor smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 302: C360–C372, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00303.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang L, Cao J, Wang H, Vo LA, Brand JG. Identification and functional characterization of a voltage-gated chloride channel and its novel splice variant in taste bud cells. J Biol Chem 280: 36150–36157, 2005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507706200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeck N, Waldegger P, Doroszewicz J, Seyberth H, Waldegger S. A common sequence variation of the CLCNKB gene strongly activates ClC-Kb chloride channel activity. Kidney Int 65: 190–197, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jentsch TJ. Discovery of CLC transport proteins: cloning, structure, function and pathophysiology. J Physiol 593: 4091–4109, 2015. doi: 10.1113/JP270043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kajioka S, Nakayama S, McCoy R, McMurray G, Abe K, Brading AF. Inward current oscillation underlying tonic contraction caused via ETA receptors in pig detrusor smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F77–F85, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00355.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawasaki M, Fukuma T, Yamauchi K, Sakamoto H, Marumo F, Sasaki S. Identification of an acid-activated Cl− channel from human skeletal muscles. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 277: C948–C954, 1999. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.5.C948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawasaki M, Suzuki M, Uchida S, Sasaki S, Marumo F. Stable and functional expression of the CIC-3 chloride channel in somatic cell lines. Neuron 14: 1285–1291, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurihara S, Creed KE. Changes in the membrane potential of the smooth muscle cells of the guinea pig urinary bladder in various environments. Jpn J Physiol 22: 667–683, 1972. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.22.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurita T, Yamamura H, Suzuki Y, Giles WR, Imaizumi Y. The ClC-7 chloride channel is downregulated by hypoosmotic stress in human chondrocytes. Mol Pharmacol 88: 113–120, 2015. doi: 10.1124/mol.115.098160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Jiang C, Hao P, Li W, Fan L, Zhou Z, Song B. Changes in T-type calcium channel and its subtypes in overactive detrusor of the rats with partial bladder outflow obstruction. Neurourol Urodyn 26: 870–878, 2007. doi: 10.1002/nau.20392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Jiang C, Song B, Yan J, Pan J. Altered expression of calcium-activated K and Cl channels in detrusor overactivity of rats with partial bladder outlet obstruction. BJU Int 101: 1588–1594, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li X, Shimada K, Showalter LA, Weinman SA. Biophysical properties of ClC-3 differentiate it from swelling-activated chloride channels in Chinese hamster ovary-K1 cells. J Biol Chem 275: 35994–35998, 2000. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002712200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lourdel S, Paulais M, Marvao P, Nissant A, Teulon J. A chloride channel at the basolateral membrane of the distal-convoluted tubule: a candidate ClC-K channel. J Gen Physiol 121: 287–300, 2003. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200208737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Malysz J, Afeli SA, Provence A, Petkov GV. Ethanol-mediated relaxation of guinea pig urinary bladder smooth muscle: involvement of BK and L-type Ca2+ channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 306: C45–C58, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00047.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manoury B, Tamuleviciute A, Tammaro P. TMEM16A/anoctamin 1 protein mediates calcium-activated chloride currents in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Physiol 588: 2305–2314, 2010. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.189506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marchenko SM, Yarotskyy VV, Kovalenko TN, Kostyuk PG, Thomas RC. Spontaneously active and InsP3-activated ion channels in cell nuclei from rat cerebellar Purkinje and granule neurones. J Physiol 565: 897–910, 2005. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.081299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuda JJ, Filali MS, Collins MM, Volk KA, Lamb FS. The ClC-3 Cl−/H+ antiporter becomes uncoupled at low extracellular pH. J Biol Chem 285: 2569–2579, 2010. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsuda JJ, Filali MS, Volk KA, Collins MM, Moreland JG, Lamb FS. Overexpression of CLC-3 in HEK293T cells yields novel currents that are pH dependent. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 294: C251–C262, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00338.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McElroy SP, Gurney AM, Drummond RM. Pharmacological profile of store-operated Ca2+ entry in intrapulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol 584: 10–20, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nobile M, Pusch M, Rapisarda C, Ferroni S. Single-channel analysis of a ClC-2-like chloride conductance in cultured rat cortical astrocytes. FEBS Lett 479: 10–14, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)01876-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orhan G, Fahlke C, Alekov AK. Anion- and proton-dependent gating of ClC-4 anion/proton transporter under uncoupling conditions. Biophys J 100: 1233–1241, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.01.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parajuli SP, Hristov KL, Sullivan MN, Xin W, Smith AC, Earley S, Malysz J, Petkov GV. Control of urinary bladder smooth muscle excitability by the TRPM4 channel modulator 9-phenanthrol. Channels (Austin) 7: 537–540, 2013. doi: 10.4161/chan.26289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parajuli SP, Soder RP, Hristov KL, Petkov GV. Pharmacological activation of small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels with naphtho[1,2-d]thiazol-2-ylamine decreases guinea pig detrusor smooth muscle excitability and contractility. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 340: 114–123, 2012. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.186213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel AC, Brett TJ, Holtzman MJ. The role of CLCA proteins in inflammatory airway disease. Annu Rev Physiol 71: 425–449, 2009. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petkov GV. Role of ion channels in urinary bladder smooth muscle function. In: Methods in Signal Transduction and Smooth Muscle, edited by Trebak M, Earley S. Portland, OR: CRC, 2018, p. 281–304. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petkov GV. Role of potassium ion channels in detrusor smooth muscle function and dysfunction. Nat Rev Urol 9: 30–40, 2011. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Picollo A, Malvezzi M, Accardi A. Proton block of the CLC-5 Cl−/H+ exchanger. J Gen Physiol 135: 653–659, 2010. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201010428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Piper AS, Large WA. Multiple conductance states of single Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in rabbit pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Physiol 547: 181–196, 2003. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.033688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Provence A, Angoli D, Petkov GV. KV7 Channel pharmacological activation by the novel activator ML213: role for heteromeric KV7.4/KV7.5 channels in guinea pig detrusor smooth muscle function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 364: 131–144, 2018. doi: 10.1124/jpet.117.243162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pusch M, Steinmeyer K, Jentsch TJ. Low single channel conductance of the major skeletal muscle chloride channel, ClC-1. Biophys J 66: 149–152, 1994. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80753-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roosen A, Wu C, Sui G, Chowdhury RA, Patel PM, Fry CH. Characteristics of spontaneous activity in the bladder trigone. Eur Urol 56: 346–353, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sala-Rabanal M, Yurtsever Z, Berry KN, Brett TJ. Novel roles for chloride channels, exchangers, and regulators in chronic inflammatory airway diseases. Mediators Inflamm 2015: 497387, 2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/497387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith AC, Parajuli SP, Hristov KL, Cheng Q, Soder RP, Afeli SA, Earley S, Xin W, Malysz J, Petkov GV. TRPM4 channel: a new player in urinary bladder smooth muscle function in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F918–F929, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00417.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steinmeyer K, Schwappach B, Bens M, Vandewalle A, Jentsch TJ. Cloning and functional expression of rat CLC-5, a chloride channel related to kidney disease. J Biol Chem 270: 31172–31177, 1995. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.52.31172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tao T, Xie J, Drumm ML, Zhao J, Davis PB, Ma J. Slow conversions among subconductance states of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel. Biophys J 70: 743–753, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79614-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thomas-Gatewood C, Neeb ZP, Bulley S, Adebiyi A, Bannister JP, Leo MD, Jaggar JH. TMEM16A channels generate Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1819–H1827, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00404.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thorneloe KS, Nelson MT. Properties of a tonically active, sodium-permeable current in mouse urinary bladder smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 286: C1246–C1257, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00501.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tomasek M, Misak A, Grman M, Tomaskova Z. Subconductance states of mitochondrial chloride channels: implication for functionally-coupled tetramers. FEBS Lett 591: 2251–2260, 2017. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wegener JW, Schulla V, Lee TS, Koller A, Feil S, Feil R, Kleppisch T, Klugbauer N, Moosmang S, Welling A, Hofmann F. An essential role of Cav1.2 L-type calcium channel for urinary bladder function. FASEB J 18: 1159–1161, 2004. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1516fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamazaki J, Duan D, Janiak R, Kuenzli K, Horowitz B, Hume JR. Functional and molecular expression of volume-regulated chloride channels in canine vascular smooth muscle cells. J Physiol 507: 729–736, 1998. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.729bs.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y, Shim WS, Park SP, Lee J, Lee B, Kim BM, Raouf R, Shin YK, Oh U. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature 455: 1210–1215, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nature07313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zifarelli G, Liantonio A, Gradogna A, Picollo A, Gramegna G, De Bellis M, Murgia AR, Babini E, Conte Camerino D, Pusch M. Identification of sites responsible for the potentiating effect of niflumic acid on ClC-Ka kidney chloride channels. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1652–1661, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00822.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]