Abstract

Prevalence of obesity is exacerbated by low rates of successful long-term weight loss maintenance (WLM). In part, relapse from WLM to obesity is due to a reduction in energy expenditure (EE) that persists throughout WLM and relapse. Thus, interventions that increase EE might facilitate WLM. In obese mice that were calorically restricted to reduce body weight by ~20%, we manipulated EE throughout WLM and early relapse using intermittent cold exposure (ICE; 4°C, 90 min/day, 5 days/wk, within the last 3 h of the light cycle). EE, energy intake, and spontaneous physical activity were measured during the obese, WLM, and relapse phases. During WLM and relapse, the ICE group expended more energy during the light cycle because of cold exposure but expended less energy in the dark cycle, which led to no overall difference in total daily EE. The compensation in EE appeared to be mediated by activity, whereby the ICE group was more active during the light cycle because of cold exposure but less active during the dark cycle, which led to no overall effect on total daily activity during WLM and relapse. In brown adipose tissue of relapsing mice, the ICE group had greater mRNA expression of Dio2 and protein expression of UCP1 but lower mRNA expression of Prdm16. In summary, these findings indicate that despite robust increases in EE during cold exposures, ICE is unable to alter total daily EE during WLM or early relapse, likely due to compensatory behaviors in activity.

Keywords: activity, cold exposure, energy expenditure, weight loss maintenance, weight regain

INTRODUCTION

Currently, more than one in three adults are afflicted with obesity (16). Obesity is a financial burden (14) linked to metabolic disease (28) and cancer (5), warranting the immediate need for successful therapeutics. Weight loss reduces the comorbidities associated with obesity (4); however, only about one in five overweight individuals successfully maintain long-term weight loss (51). In part, this recidivism is due to biological adaptations that cumulate during a caloric deficit and result in a reduced energy expenditure (EE) (26). Moreover, this diminished EE may persist regardless of the duration of weight loss maintenance (WLM) (32) and throughout weight regain (11). Therefore, interventions that offset the reduction in EE during a caloric deficit may facilitate WLM.

Adipose tissue has a major role in both energy storage and expenditure. Thermogenic adipose tissue (TAT), which includes brown and beige fat, dissipates energy to maintain body temperature in cold environments through nonshivering mechanisms (18). Furthermore, TAT may contribute to basal metabolic rate (44) and diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT) (23, 33, 40, 44, 45), indicating that TAT might have an impact on metabolism outside of maintaining body temperature. Some evidence suggests that caloric restriction impairs thermogenic potential of TAT, reducing norepinephrine turnover in rats (54) and expression of genes involved with thermogenesis in humans (1), although weight loss has also been shown to increase expression of thermogenic genes in TAT (13). It has been postulated that therapeutically targeting TAT could facilitate WLM by counteracting metabolic adaptations induced by a caloric deficit (27).

Acute cold exposure is capable of increasing EE via contractions and uncoupling in skeletal muscle (3) and uncoupling and futile cycles in TAT (6, 22). Moreover, cold exposure, through shivering and/or nonshivering mechanisms, provokes a release of factors that have beneficial effects on whole body metabolism (19, 25). Long-term acclimation to cold remodels TAT to improve its thermogenic capacity (21, 35) and augments the thermogenic response to cold (8, 30, 52). Despite cold exposure being able to increase EE and beneficially modulate TAT function, few studies have investigated the physiological response to intermittent cold exposure (ICE) during WLM and relapse. Therefore, using a well-established rodent model of obesity, WLM, and relapse, we tested the hypothesis that ICE would promote WLM and attenuate a positive energy balance during relapse by increasing EE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal treatment and study design.

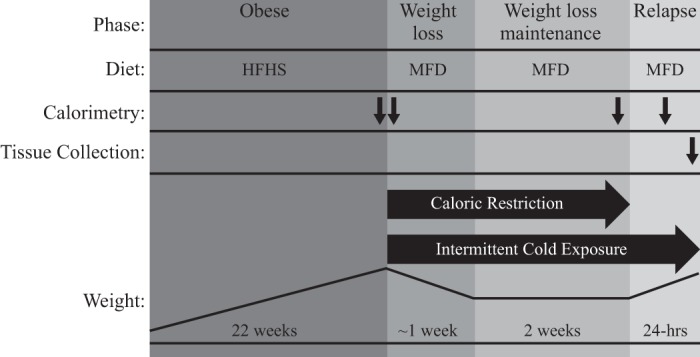

The study design is outlined in Fig. 1. Eight-week-old male FVB mice (n = 14) were individually housed near thermoneutrality (27°C) and kept on a 14-h light, 10-h dark cycle. To induce obesity, mice were provided a high-fat, high-sugar diet (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ; RD no. D15031601; 40% kcal from fat, rest of diet composition provided in Supplemental Table S1, available online at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7859960.v2) for 22 wk. Mice were then calorically restricted to ~50% of ad libitum energy intake with a medium-fat diet (Research Diets; RD no. D07091301; 24.9% kcal from fat, rest of diet composition provided in Supplemental Table S1) to induce ~20% weight loss, which was then maintained for 2 wk by titrating feeding. At the end of the 2-wk WLM phase, mice were provided ad libitum access to food for 1 day. On the final day of study, mice were anesthetized using isoflurane, and adipose tissues were harvested and flash frozen. Mice were fasted for 2 h before euthanization. Procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at CU Anschutz Medical Campus.

Fig. 1.

Study design. After receiving a high-fat-diet to promote obesity, all mice were calorically restricted to support ~20% weight loss maintenance and then allowed to eat ad libitum for 1 day. At the initiation of weight loss and throughout the remainder of the study, a group of mice was subjected to the intermittent cold exposure protocol. Metabolic phenotype was periodically characterized and tissues were collected at the conclusion of the study. Black arrows designate when each measurement took place. Calorimetry at the initiation of weight loss was only performed during the cold exposure to establish baseline metabolism. Diagram is not drawn to scale. HFHS, high-fat high-sugar; MFD, medium-fat diet.

Intermittent cold exposure.

After the obese phase (i.e., at the initiation of weight loss and for the remainder of the study), a subset of mice was randomized to ICE. The ICE intervention was established using an environmental chamber set to 4°C and consisted of 90-min exposures, 5 times/wk, within 3 h before the dark cycle. Euthanization occurred immediately after the final cold exposure.

Metabolic phenotyping and body composition.

Total lean and fat mass were determined using quantitative magnetic resonance (EchoMR; Echo Medical Systems, Houston, TX). To measure EE, indirect calorimetry was performed using a metabolic monitoring system (Oxymax CLAMS-8M; Columbus Instruments, Columbus, OH) at an ambient temperature near thermoneutrality (27°C). Component analysis of total daily EE (TEE) was performed to determine resting (REE) and nonresting energy expenditure (NREE). Cold-induced thermogenesis (CIT) and activity during cold exposure were determined using a separate eight-cage calorimetry system housed within an environmental chamber set to 4°C. Mice had at least 3 days of acclimation in the calorimeter before the recorded day of measurement. The recorded day of measurement was the final day of the obese, WLM, and relapse phase. Activity was determined by infrared beam breaks. Formulas and methods to derive components of activity and EE are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Methods and calculations for component analysis

| Component | Method or Calculation |

|---|---|

| Energy balance | Energy intake − TEE |

| REE | Average of 3 lowest measures of EE |

| NREE | TEE − REE; used REE from WLM day to derive relapse NREE |

| CIT | EE while in cold chamber minus REE |

| Relapse-induced DIT | (NREE during relapse − CIT during relapse) − (NREE during WLM − CIT during WLM) |

| Total activity, counts | Summation of all beam breaks |

| Ambulatory activity, counts | 3 or more sequential beam breaks in series |

| Nonambulatory activity, counts | Total activity − ambulatory activity |

CIT, cold-induced thermogenesis; DIT, diet-induced thermogenesis; NREE, nonresting energy expenditure; REE, resting energy expenditure; TEE, total energy expenditure; WLM, weight loss maintenance.

Adipose gene expression.

Frozen inguinal (iWAT), anterior subcutaneous (asWAT), and interscapular (brown; BAT) adipose tissues were pulverized and then homogenized in QIAzol (Qiagen, Germantown, MD), and RNA was extracted according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was then reverse transcribed using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Quantitative reverse transcription PCR was quantified using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). Genes of interest were designed using NCBI’s primer3/BLAST. Ckmt1 was acquired from a previous publication (22). Primers are listed in Table 2. Reactions were run in duplicate on an iQ5 Real-Time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad) along with a no-template control per gene. Validation experiments were performed to demonstrate that efficiencies of target and reference genes were equivalent. Data were normalized to ribosomal (18S) and Gapdh mRNA using the comparative Ct method.

Table 2.

Primers for qRT-PCR

| Gene | GenBank No. | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pgc1α | NM_008904.2 | TCTCAGTAAGGGGCTGGTTG | AGCAGCACACTCTATGTCACTC |

| Dio2 | NM_010050.3 | CTTCTGAGCCGCTCCAAGTC | CACCCAGTTTAACCTGTTTGTAGG |

| Ucp1 | NM_009463.3 | GGGCATTCAGAGGCAAATCAGCTT | TTGTTTCCGAGAGAGGCAGGTGTT |

| Prdm16 | NM_001177995.1 | ATCCGTGTAGCGTGTTCCTG | CGGAATGTGGGGTCCTCATC |

| Cidea | NM_007702.2 | TCAGACCTTAAGGGACAACACGCA | TTCTTTGGTTGCTTGCAGACTGGG |

| Ckmt1 | TGAGGAGACCTATGAGGTATTTGC | TCATCAAAGTAGCCAGAACGG | |

| 18S | XR_877120.2 | TCCGATAACGAACGAGAC | CTAAGGGCATCACAGACC |

| Gapdh | NM_008084.3 | GTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTT | TGGCAACAATCTCCACTTTGCCAC |

18S, ribosomal; Cidea, cell death-inducing DFFA-like effector a; Ckmt1, creatine kinase mitochondrial 1; Dio2, type II iodothyronine deiodinase; Gapdh, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; Pgc1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha; Prdm16, PR domain zinc finger protein 16; Ucp1, uncoupling protein 1.

Western blot analysis.

Pulverized adipose tissues were homogenized in 500 μl of methanol-saline (2:1) vol/vol solution (saline = 0.127M NaCl). After homogenization, 1 ml of isooctane-ethyl acetate (3:1) vol/vol solution was added to the samples. Samples were then vortexed vigorously and sat at room temperature for 5 min. Samples were centrifuged at 1,500 g at 4°C for 1 min to separate phases, and the upper organic layer was removed. Samples were centrifuged again at 14,000 g at 4°C for 15 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the protein pellet was washed in 1 ml of methanol-saline (2:1) vol/vol solution for 5 min on ice. Samples were then centrifuged at 14,000 g at 4°C for 15 min, and the supernatant was discarded. Protein pellets were then briefly air-dried and reconstituted with 5% SDS solution. Protein concentrations were determined by bicinchoninic acid analysis (Pierce BCA protein assay; Thermo Fisher, Rockford, IL). Identification and quantification of proteins was determined by capillary electrophoresis size-based sorting using the uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) antibody (1:10; no.14670, Cell Signaling) in the Wes system (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA), and data were analyzed using Compass software (ProteinSimple). BAT was loaded at a 0.05 mg/ml protein concentration and asWAT was loaded at a 0.2 mg/ml protein concentration. UCP1 was normalized to total protein using the Total Protein Detection Module in the Wes (ProteinSimple).

Histology.

At euthanization, a portion of BAT and asWAT was fixed in 10% formalin for 24–48 h, embedded, and sectioned (4 µm). Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Histologic images were captured on an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with a 4MP Macrofire digital camera using the PictureFrame Application 2.3.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA) or R [version 3.4.3, “Kite-Eating Tree” (30a)]. Statistical significance was assessed using one- or two-way repeated measures ANOVA with planned comparisons using a Fisher’s least significant difference test. Planned comparisons when using two-way repeated measures ANOVA were between control and ICE during WLM and between control and ICE during relapse. Planned comparisons when using one-way repeated measures ANOVA were performed between the means of all groups. When comparing just two groups, a two-tailed t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used when appropriate. Associations were determined using a Pearson product-moment correlation. Significance was set at P ≤ 0.05. Cohen’s d was used to assess effect sizes.

RESULTS

Compensation for cold-induced thermogenesis over 24 h.

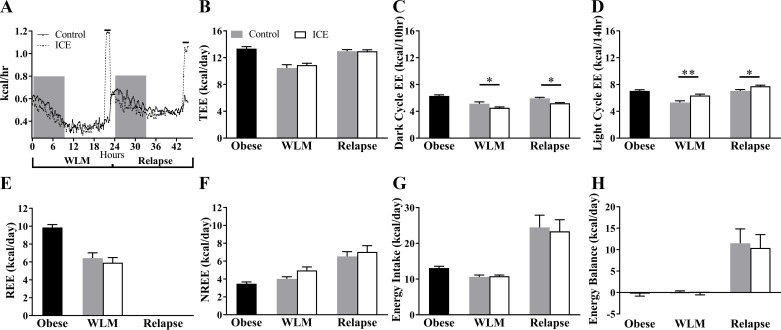

Despite the large acute cold-induced increases in metabolic rate (Fig. 2A), there were no differences in TEE with ICE during WLM or relapse (P > 0.05; Fig. 2B). During WLM and relapse, the ICE group expended less energy during the dark cycle (P = 0.038 and P = 0.014, respectively; Fig. 2C) and expended more energy during the light cycle (P = 0.0026 and P = 0.035, respectively; Fig. 2D). Component analysis of TEE revealed no effect of ICE on REE (P > 0.05; Fig. 2E) during WLM or NREE during WLM and relapse (P > 0.05; Fig. 2F). Additionally, no differences in energy intake (P > 0.05; Fig. 2G), energy balance (P > 0.05; Fig. 2H), respiratory exchange ratios (Table 3), or body weight and composition (P > 0.05; Table 4) were observed with ICE at any time point. Numeric values for metabolic data are provided in Table 3. Absolute BAT mass tended to be higher with ICE (P = 0.08) and was significantly higher when normalized to body weight (P = 0.014; Table 5).

Fig. 2.

Intermittent cold exposure (ICE) does not increase 24-h energy expenditure (EE). A: time course of metabolic rate from food drop on the last day of weight loss maintenance (WLM) to time of euthanization. Lines above graph designate when the cold exposure occurred. B: daily EE (TEE). C: dark cycle EE. D: light cycle EE. E: daily resting EE (REE); WLM REE used for relapse REE. F: daily nonresting EE (NREE). G: daily energy intake. H: daily energy balance. Values are means ± SE. Obese, n = 14 mice; all other groups, n = 7. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Significance was assessed by Fisher’s least significant difference test between control and ICE groups.

Table 3.

Metabolic phenotype

| WLM |

Relapse |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obese | Control | ICE | Control | ICE | |

| N | 14 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Energetics, kcal | |||||

| Energy intake | 13.08 ± 0.52 | 10.60 ± 0.54 | 10.81 ± 0.33 | 24.47 ± 3.43 | 23.37 ± 3.24 |

| Energy balance | −0.26 ± 0.58 | 0.15 ± 0.23 | −0.08 ± 0.48 | 11.50 ± 3.35 | 10.41 ± 3.10 |

| TEE | 13.34 ± 0.30 | 10.45 ± 0.51 | 10.89 ± 0.27 | 12.97 ± 0.23 | 12.95 ± 0.23 |

| Dark cycle EE | 6.30 ± 0.17 | 5.13 ± 0.28 | 4.53 ± 0.13* | 5.93 ± 0.16 | 5.21 ± 0.10* |

| Light cycle EE | 7.04 ± 0.18 | 5.32 ± 0.25 | 6.36 ± 0.21** | 7.04 ± 0.20 | 7.75 ± 0.15* |

| REE | 9.87 ± 0.32 | 6.44 ± 0.59 | 5.92 ± 0.57 | ||

| NREE | 3.47 ± 0.19 | 4.01 ± 0.24 | 4.97 ± 0.38 | 6.53 ± 0.54 | 7.03 ± 0.71 |

| Relapse-induced DIT | 2.52 ± 0.40 | 2.16 ± 0.39 | |||

| Relapse-induced DIT (as % of energy intake) | 10.30 ± 0.96 | 8.79 ± 1.00 | |||

| CIT | 1.39 ± 0.07 | 1.30 ± 0.07# | |||

| Respirometry, l | |||||

| Total V̇o2 | 2.72 ± 0.06 | 2.12 ± 0.10 | 2.21 ± 0.06 | 2.56 ± 0.05 | 2.55 ± 0.04 |

| Dark cycle | 1.28 ± 0.03 | 1.02 ± 0.06 | 0.89 ± 0.03* | 1.17 ± 0.04 | 1.02 ± 0.02* |

| Light cycle | 1.44 ± 0.03 | 1.10 ± 0.05 | 1.32 ± 0.04** | 1.39 ± 0.03 | 1.54 ± 0.02* |

| ICE | 0.37 ± 0.01 | 0.34 ± 0.01# | |||

| Total V̇co2 | 2.40 ± 0.06 | 1.93 ± 0.09 | 2.00 ± 0.04 | 2.59 ± 0.08 | 2.60 ± 0.09 |

| Dark cycle | 1.15 ± 0.03 | 1.01 ± 0.05 | 0.91 ± 0.02 | 1.19 ± 0.03 | 1.07 ± 0.03* |

| Light cycle | 1.25 ± 0.04 | 0.91 ± 0.04 | 1.09 ± 0.04* | 1.40 ± 0.07 | 1.53 ± 0.07 |

| ICE | 0.27 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.01 | |||

| RER | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.91 ± 0.01 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 1.01 ± 0.03 | 1.02 ± 0.03 |

| Dark cycle | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.99 ± 0.01 | 1.02 ± 0.02 | 1.02 ± 0.02 | 1.05 ± 0.02 |

| Light cycle | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 1.00 ± 0.04 | 1.00 ± 0.04 |

| ICE | 0.74 ± 0.00 | 0.84 ± 0.03# | |||

| Activity, counts × 103 | |||||

| Total | 39.53 ± 6.32 | 42.72 ± 6.16 | 49.54 ± 7.13 | 41.56 ± 7.05 | 36.12 ± 4.60 |

| Dark cycle | 27.68 ± 5.98 | 31.22 ± 6.39 | 19.48 ± 5.32 | 29.15 ± 6.30 | 14.99 ± 2.14 |

| Light cycle | 11.84 ± 0.97 | 11.50 ± 1.22 | 30.06 ± 4.30*** | 12.41 ± 1.59 | 21.13 ± 3.85* |

| ICE | 19.31 ± 3.77 | 11.69 ± 3.58## | |||

| Ambulatory | 23.55 ± 5.02 | 25.73 ± 5.06 | 31.28 ± 5.69 | 24.04 ± 5.13 | 20.05 ± 3.37 |

| Dark cycle | 17.35 ± 4.78 | 20.20 ± 5.18 | 11.76 ± 4.25*** | 17.76 ± 4.64 | 7.83 ± 1.53* |

| Light cycle | 6.20 ± 0.66 | 5.52 ± 0.98 | 19.52 ± 3.48 | 6.28 ± 1.10 | 12.22 ± 3.02 |

| ICE | 14.04 ± 3.27 | 8.06 ± 3.02## | |||

| Nonambulatory | 15.98 ± 1.37 | 17.00 ± 1.21 | 18.27 ± 1.53 | 17.52 ± 1.93 | 16.07 ± 1.44 |

| Dark cycle | 10.34 ± 1.23 | 11.02 ± 1.28 | 7.72 ± 1.11 | 11.39 ± 1.66 | 7.16 ± 0.67* |

| Light cycle | 5.64 ± 0.42 | 5.98 ± 0.44 | 10.55 ± 0.90*** | 6.13 ± 0.51 | 8.91 ± 1.02** |

| ICE | 5.27 ± 0.53 | 3.62 ± 0.6## | |||

Values are means ± SE; n, number of mice. Measurements were taken during the final day of each phase and are total values taken over 24 h unless noted otherwise. Intermittent cold exposure (ICE) values are totals over 90 min of cold exposure in the cold exposed group only. CIT, cold-induced thermogenesis; DIT, diet-induced thermogenesis; EE, energy expenditure; NREE, nonresting energy expenditure; REE, resting energy expenditure; RER, respiratory exchange ratio; TEE, total energy expenditure; V̇o2, oxygen consumption; V̇co2, carbon dioxide production; WLM, weight loss maintenance

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001; significance was assessed by Fisher’s least significant difference test between control and ICE groups.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01; significance assessed with two-tailed paired t-test.

Table 4.

Body weights and composition

| WLM |

Relapse |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obese | Control | ICE | Control | ICE | |

| n | 14 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Weight, g | |||||

| Total | 38.6 ± 1.5 | 29.9 ± 2.1 | 30.2 ± 0.7 | 33.8 ± 1.4 | 32.6 ± 0.8 |

| Fat | 11.6 ± 1.2 | 5.5 ± 1.5 | 6.1 ± 0.8 | 6.3 ± 1.2 | 6.5 ± 0.8 |

| Lean | 20.8 ± 0.5 | 19.3 ± 0.6 | 19.1 ± 0.3 | 21.0 ± 0.5 | 20.7 ± 0.3 |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of mice. Measurements were taken during the final day of each phase. ICE, intermittent cold exposure; WLM, weight loss maintenance.

Table 5.

Tissue weights

| Tissue Weights, g | Control | ICE |

|---|---|---|

| n | 7 | 7 |

| Gastrocnemius | 0.15 ± 0.01 | 0.14 ± 0.004 |

| *BW, kg−1 | 4.51 ± 0.16 | 4.39 ± 0.14 |

| Liver | 1.50 ± 0.07 | 1.36 ± 0.09 |

| *BW, kg−1 | 44.66 ± 2.15 | 41.66 ± 1.99 |

| Adipose | ||

| Epididymal | 0.37 ± 0.05 | 0.36 ± 0.02 |

| *BW, kg−1 | 11.05 ± 1.62 | 11.23 ± 0.79 |

| Inguinal (iWAT) | 0.31 ± 0.06 | 0.28 ± 0.05 |

| *BW, kg−1 | 8.94 ± 1.51 | 8.32 ± 1.29 |

| Anterior (asWAT) | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.33 ± 0.05 |

| *BW, kg−1 | 9.74 ± 1.19 | 9.98 ± 1.12 |

| Interscapular (BAT) | 0.20 ± 0.03 | 0.27 ± 0.03 |

| *BW, kg−1 | 5.68 ± 0.57 | 8.32 ± 0.73* |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of mice. Data analyzed using two-tailed t-test. All measurements derived from the end of relapse. iWAT, inguinal adipose tissue; asWAT, anterior subcutaneous adipose tissue; BAT, interscapular (brown) adipose tissue; BW, body weight; ICE, intermittent cold exposure

P < 0.05. Data analyzed using two-tailed t-test.

Spontaneous physical activity.

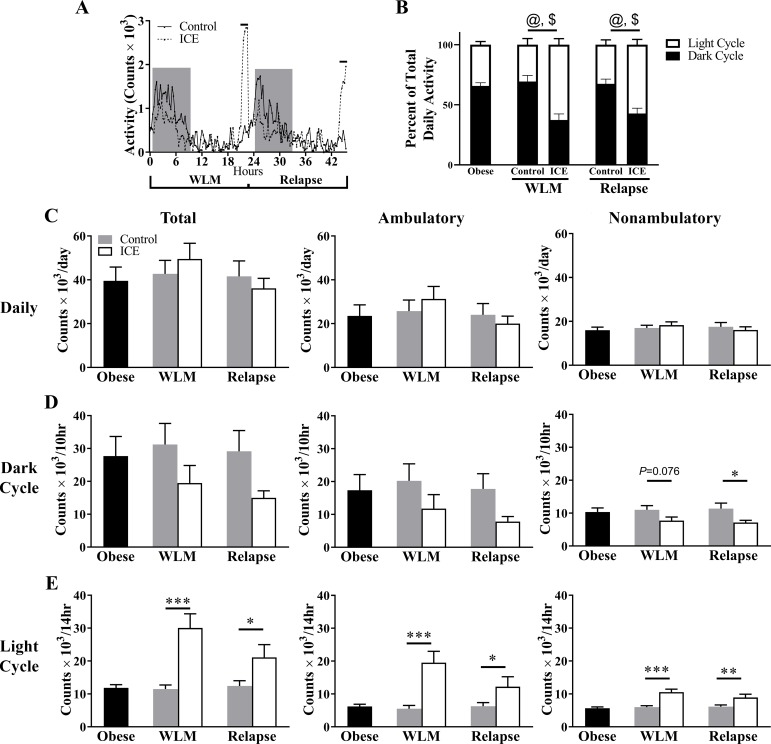

Activity throughout the day is provided in Fig. 3A. Compared with controls, ICE changed the temporal pattern of activity as expressed by percentage of total activity, whereby ICE led to greater activity in light cycle and less activity in the dark cycle during WLM and relapse (P < 0.001 for all comparisons; Fig. 3B). However, no differences in daily total, ambulatory, or nonambulatory activity were observed with ICE during WLM or relapse (P > 0.05; Fig. 3C). With ICE during WLM, nonambulatory activity tended to be lower in the dark cycle (P = 0.076; Fig. 3D), and total, ambulatory, and nonambulatory activity were higher in the light cycle (P < 0.001 for all comparisons; Fig. 3E). With ICE during relapse, nonambulatory activity was lower in the dark cycle (P = 0.046; Fig. 3D), and total, ambulatory, and nonambulatory activity were higher in the light cycle (total P = 0.024, ambulatory P = 0.048, nonambulatory P = 0.0072; Fig. 3E). Numeric values for activity data are provided in Table 3. Of note, when comparing ICE to controls, the temporal pattern of activity reflected what was observed with EE (Table 6), suggesting activity mediated at least some of the differences observed with EE.

Fig. 3.

Intermittent cold exposure (ICE) alters spontaneous activity during the light and dark cycle. A: time course of activity from food drop on the final day of weight loss maintenance (WLM) to relapse. Line above graph designates when cold exposure occurred. B: total light and dark cycle activity expressed as a percentage of total daily activity. @P < 0.001 between dark cycle planned comparisons; $P < 0.001 between light cycle planned comparisons. C: daily total, ambulatory, and nonambulatory activity. D: dark cycle total, ambulatory, and nonambulatory activity. E: light cycle total, ambulatory, and nonambulatory activity. Counts determined by beam breaks. Values are means ± SE. Obese, n = 14 mice; all other groups, n = 7. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. Significance was assessed by Fisher’s least significant difference test between control and ICE groups.

Table 6.

Summary of metabolic phenotype of ICE compared with control during WLM and relapse

| EE | Nonambulatory Activity | |

|---|---|---|

| WLM (total) | – | – |

| Dark cycle | ↓ | ↓ |

| Light cycle | ↑ | ↑ |

| Relapse (total) | – | – |

| Dark cycle | ↓ | ↓ |

| Light cycle | ↑ | ↑ |

EE, energy expenditure; ICE, intermittent cold exposure; WLM, weight loss maintenance. ↑/↓ = Cohen’s d value greater than 0.8 or less than −0.8. Dashed lines indicate a Cohen’s d value less than 0.8 and greater than −0.8.

Cold-induced activity, cold-induced thermogenesis, and diet-induced thermogenesis.

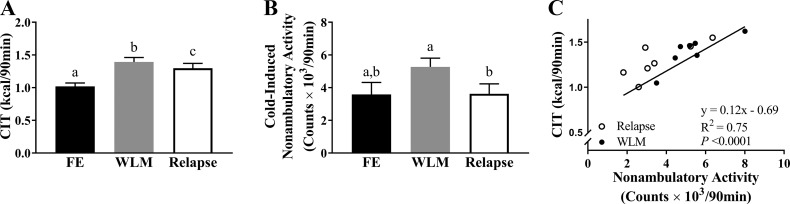

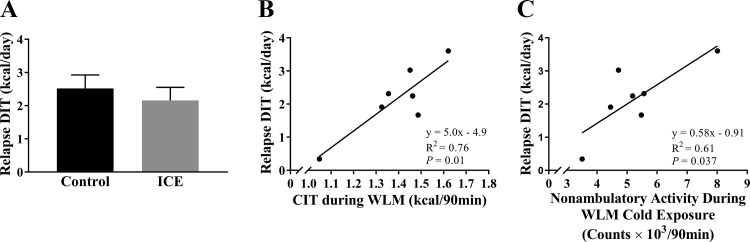

Mice subjected to ICE increased their CIT from the first exposure relative to WLM and relapse (P = 0.0013 and P = 0.013, respectively; Fig. 4A), but CIT was reduced during relapse compared with WLM (P = 0.032; Fig. 4A). Similarly, cold-induced nonambulatory activity was reduced during relapse compared with WLM (P = 0.0028; Fig. 4B). Total and ambulatory activity were also reduced during relapse compared with WLM (Table 3). Nonambulatory activity during the cold exposure positively correlated with CIT during both WLM and relapse (R2 = 0.75, P < 0.001; Fig. 4C). Because a relationship has been previously observed between DIT and CIT, we then investigated if ICE had any effect on relapse-induced DIT. Relapse-induced DIT did not differ between ICE and controls (P > 0.05; Fig. 5A), but CIT and cold-induced nonambulatory activity during WLM were both positively associated with relapse-induced DIT (R2 =0.76, P = 0.01 and R2 = 0.61, P = 0.037, respectively; Fig. 5, B and C).

Fig. 4.

Thermogenic response to cold is enhanced with intermittent cold exposure (ICE) during weight loss maintenance (WLM) but is blunted during relapse. Metabolic measurements consist of totals during 90-min cold exposure. A: cold-induced thermogenesis (CIT) during first exposure (FE), WLM, and relapse. B: nonambulatory activity counts during first exposure, WLM, and relapse. C: relationship between nonambulatory activity and CIT during WLM and relapse. Values are means ± SE. All groups, n = 7 mice. a,b,cGroups with a different letter designation are significantly different (P < 0.05). Significance was assessed by Fisher’s least significant difference test between all groups. Association was determined by Pearson’s product-moment correlation.

Fig. 5.

Thermogenesis and activity during weight loss maintenance (WLM) cold exposure is associated with diet-induced thermogenesis (DIT) during relapse. A: estimated DIT induced by relapse. B: association between cold-induced thermogenesis (CIT) during WLM and DIT during relapse. C: association between cold-induced nonambulatory activity during WLM and DIT during relapse. Formula for estimating DIT during relapse is listed in Table 1. Values are means ± SE. All groups, n = 7 mice. Associations were determined by Pearson’s product-moment correlation. ICE, intermittent cold exposure.

Adipose adaptation to intermittent cold exposure.

In BAT of relapsing mice, expression of Dio2 mRNA was higher and expression of Prdm16 mRNA was lower with ICE (Dio2 P = 0.002, Prdm16 P = 0.021; Fig. 6A). In asWAT of relapsing mice, expression of Dio2 was higher with ICE (P = 0.006; Fig. 6B). No differences in thermogenic gene expression were observed with ICE in iWAT (P > 0.05; Supplemental Fig. S1, available online at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7859960.v2). UCP1 protein expression was significantly higher in BAT (P = 0.036; Fig. 6C) and trended toward being higher in asWAT (P = 0.084; Fig. 6D) with ICE. H&E images of BAT and asWAT did not display any obvious differences with ICE (Fig. 6E). Moreover, cell size of asWAT, number of beige cells present in asWAT, and lipid droplet sizes of BAT were not statistically different with ICE (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Adipose adaptation to intermittent cold exposure (ICE). Expression of thermogenic genes in interscapular (brown) adipose tissue (BAT) (A) and anterior subcutaneous adipose tissue (asWAT) (B). Protein expression of uncoupled protein 1 (UCP1) in BAT (C) and asWAT (D); representative images of protein expression are presented above graph. Representative H&E stained images of BAT and asWAT (E). BAT was imaged at ×400 magnification and asWAT was imaged at ×200 magnification. Values are means ± SE. All groups, n = 5–7 mice. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Significance was assessed by two-tailed t-test or Mann-Whitney U test.

DISCUSSION

Leveraging thermoregulation is a potential intervention to treat obesity because of its well-known effects on EE (43). We made the novel observation that acute cold-induced increases in EE are compensated for during WLM and early relapse. These ICE-induced changes in EE temporally coincided with changes in spontaneous activity, suggesting the compensation was, at least in part, mediated by activity. ICE also augmented the thermogenic response to cold exposure, although compared with WLM, this response was blunted during relapse, likely due to a reduction in cold-induced activity. Additionally, cold-induced activity and thermogenesis during WLM positively associated with relapse-induced DIT, although relapse-induced DIT was not different between the ICE and control groups. Interestingly, in BAT of relapsing mice, expression of Dio2 mRNA and UCP1 protein was higher, whereas expression of Prdm16 mRNA was lower with ICE. Altogether, these results provide the first evidence for behavioral compensation masking the effect of cold exposure on TEE during WLM and relapse.

Contrary to our hypothesis, ICE did not affect energy balance during WLM or relapse, despite provoking large acute increases in EE during the cold exposures. With ad libitum food intake, ICE fails to alter energy balance because of an increase in energy intake to match for the cold-induced increase in EE (31, 53). Interestingly, even when we briefly added ad libitum feeding back in during relapse, energy intake was not different with ICE, and, because of metabolic compensation, there were no differences in energy balance. Similarly, housing rodents in a cold environment throughout a pair-fed relapse does not prevent rapid fat and weight regain because of persistent metabolic adaptations that cold exposure does not override (12). Taken together, these data would suggest that ICE is ineffective at altering energy balance during WLM or relapse.

During WLM and relapse, we noted that activity mirrored the temporal pattern of EE with ICE relative to controls, suggesting that mice subjected to ICE leverage activity to regulate EE. This is a similar phenotype to what is observed with exercise. For example, when mice voluntarily exercise using a running wheel, they reduce their off-wheel activity, and this reduction in off-wheel activity attenuates the effect exercise has on TEE and balance (24). Additionally, as seen with high levels of exercise, we cannot rule out that energetic compensation with ICE may have been mediated by increased economy of movement (41, 47) or reductions in resting (39) or sleeping (48) metabolic rate. Of note, studies that increase activity with exercise typically observe only partial compensation in components of TEE (29); therefore, TEE is still elevated with increased activity. However, we observed complete energetic compensation when using cold exposure to manipulate EE during WLM and relapse. Future studies are required to determine the reason for this discrepancy.

During relapse overfeeding, we found that CIT was blunted compared with the last day of WLM, and this was likely due to a reduction in activity during the cold exposure. It is possible that the heat produced from DIT during the relapse-induced overfeeding may have offset the need to employ activity thermogenesis to maintain body temperature, as others have found that diet or CIT is masked or reduced when implemented simultaneously (9, 42). Alternatively, the reduction in activity during the relapse cold exposure may have been caused by a reduced drive to be active during refeeding (7). An impaired nonshivering thermogenesis may also be responsible for the reduction in CIT during relapse, as it has been shown that cold-induced BAT activity is reduced if cold exposure occurs postprandially (46); indicating that BAT-mediated thermogenesis is recruited to a lesser extent in a cold environment after food intake.

In relapsing mice, the majority of thermogenic genes examined were not elevated with ICE. The lack of differences observed may have been due to the effect of overfeeding on TAT gene expression; it has been shown that compared with WAT, BAT genes involved with nutrient uptake and metabolism are increased after a meal (40). Additionally, weight loss may independently increase transcription of thermogenic genes in TAT (13), and, in this paradigm, adding cold exposure may be ineffective at amplifying this response. Unfortunately, we do not have molecular data in the obese and WLM mice; therefore, additional studies are required to confirm these hypotheses. Nevertheless, we found that UCP1 protein expression was higher in BAT with ICE, suggesting that ICE induced an adaptation in this tissue.

Interestingly, in BAT we found that ICE increased expression of Dio2 mRNA, which encodes the enzyme responsible for converting the prohormone thyroxine into the active form tri-iodothyronine (2), and reduced expression of Prdm16 mRNA, which encodes the transcription factor that regulates differentiation into and maintenance of BAT (17, 20, 34). Although speculative, it is possible that the induction of Dio2 is due to its role in the immediate response to cold to rapidly stimulate thermogenesis (10), whereas the reduction in Prdm16 may be part of a feedback to prevent excessive EE. Clearly, future studies are needed to definitively determine these observations.

An association between CIT and DIT with overfeeding is inconsistently observed, as some have found a relationship (50) while others have not (30). With our paradigm, CIT and the increased activity during cold stress were coincidently observed during WLM, and both parameters positively correlated with DIT on the subsequent relapse day. However, if CIT is associated with DIT independent of activity, we should have seen an increase in DIT with ICE because CIT increased after repeated ICEs. Furthermore, both acute and chronic exercise have been shown to potentiate DIT (37, 49, 55). Therefore, these observations suggest that cold-induced activity may have mediated the association between CIT during WLM and relapse-induced DIT.

Our interpretations are somewhat limited because of our study design. We did not carry out relapse more than 1 day; hence, we are unable to extrapolate our results to what may have happened if we allowed further weight regain. During relapse, because rodents ate continuously throughout the day, we were unable to determine REE during relapse without a DIT influence (36); therefore, we used REE from WLM as our relapse REE. Additionally, we were unable to account for DIT in the WLM phase; therefore, our calculation of relapse-induced DIT is likely an underestimate of absolute DIT. The estimate of relapse-induced DIT may also be influenced by differences in activity EE from WLM to relapse; however, measures of activity were similar from WLM to relapse in both the ICE and control groups, so this influence is likely negligible. This study was also not designed to discern the mechanisms that drive compensatory reductions in activity. The brain, specifically the orexin system, has a critical role in mediating spontaneous physical activity (15), and future studies will need to investigate this tissue to address the mechanisms that drive the compensatory reductions in activity with ICE.

Strategies that promote long-term WLM will need to target both sides of the energy balance equation. Here we have shown that ICE is capable of robustly increasing EE during cold exposures but provokes compensatory behaviors that mask any effect of ICE on TEE during WLM and the first day of relapse. These findings demonstrate that manipulating thermogenesis with ICE while dieting may be an ineffective approach to facilitate WLM or attenuate weight regain during a relapse.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Aging Grant U54 AG062319 and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant P50 HD073063 (to P. S. MacLean); National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences fellowships TR001081 TL1 (to D. M. Presby and R. M. Foright) and KL2 CDA (to V. D. Sherk); NIDDK Grant K01 DK109079 (to M. C. Rudolph); and NIDDK Grant F31 DK115238 (to R. M. Foright). We appreciate the support from the Colorado Nutrition Obesity Research Center [National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) P30 DK48520].

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.M.P. and P.S.M. conceived and designed research; D.M.P., R.M.F., J.A. Houck, G.C.J., and D.J.O. performed experiments; D.M.P., M.C.R., D.J.O., and P.S.M. analyzed data; D.M.P., M.R.J., M.C.R., V.D.S., D.J.O., E.L.M., and P.S.M. interpreted results of experiments; D.M.P. prepared figures; D.M.P. drafted manuscript; D.M.P., M.R.J., M.C.R., V.D.S., R.M.F., E.L.M., and P.S.M. edited and revised manuscript; D.M.P., M.R.J., M.C.R., V.D.S., R.M.F., J.A. Houck, G.C.J., E.L.M., J.A. Higgins, and P.S.M. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barquissau V, Léger B, Beuzelin D, Martins F, Amri EZ, Pisani DF, Saris WHM, Astrup A, Maoret JJ, Iacovoni J, Déjean S, Moro C, Viguerie N, Langin D. Caloric restriction and diet-induced weight loss do not induce browning of human subcutaneous white adipose tissue in women and men with obesity. Cell Reports 22: 1079–1089, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianco AC, McAninch EA. The role of thyroid hormone and brown adipose tissue in energy homoeostasis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 1: 250–258, 2013. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70069-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blondin DP, Daoud A, Taylor T, Tingelstad HC, Bézaire V, Richard D, Carpentier AC, Taylor AW, Harper ME, Aguer C, Haman F. Four-week cold acclimation in adult humans shifts uncoupling thermogenesis from skeletal muscles to brown adipose tissue. J Physiol 595: 2099–2113, 2017. doi: 10.1113/JP273395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bray GA, Heisel WE, Afshin A, Jensen MD, Dietz WH, Long M, Kushner RF, Daniels SR, Wadden TA, Tsai AG, Hu FB, Jakicic JM, Ryan DH, Wolfe BM, Inge TH. The science of obesity management: an endocrine society scientific statement. Endocr Rev 39: 79–132, 2018. doi: 10.1210/er.2017-00253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calle EE, Thun MJ. Obesity and cancer. Oncogene 23: 6365–6378, 2004. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Brown adipose tissue: function and physiological significance. Physiol Rev 84: 277–359, 2004. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Challet E, Pévet P, Malan A. Effect of prolonged fasting and subsequent refeeding on free-running rhythms of temperature and locomotor activity in rats. Behav Brain Res 84: 275–284, 1997. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(97)83335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cottle W, Carlson LD. Adaptive changes in rats exposed to cold; caloric exchange. Am J Physiol 178: 305–308, 1954. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1954.178.2.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dauncey MJ. Influence of mild cold on 24 h energy expenditure, resting metabolism and diet-induced thermogenesis. Br J Nutr 45: 257–267, 1981. doi: 10.1079/BJN19810102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jesus LA, Carvalho SD, Ribeiro MO, Schneider M, Kim S-W, Harney JW, Larsen PR, Bianco AC. The type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase is essential for adaptive thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 108: 1379–1385, 2001. doi: 10.1172/JCI200113803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dulloo AG, Girardier L. Adaptive changes in energy expenditure during refeeding following low-calorie intake: evidence for a specific metabolic component favoring fat storage. Am J Clin Nutr 52: 415–420, 1990. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dulloo AG, Seydoux J, Girardier L. Dissociation of enhanced efficiency of fat deposition during weight recovery from sympathetic control of thermogenesis. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 269: R365–R369, 1995. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.2.R365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabbiano S, Suárez-Zamorano N, Rigo D, Veyrat-Durebex C, Stevanovic Dokic A, Colin DJ, Trajkovski M. Caloric restriction leads to browning of white adipose tissue through type 2 immune signaling. Cell Metab 24: 434–446, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkelstein EA, Trogdon JG, Cohen JW, Dietz W. Annual medical spending attributable to obesity: payer-and service-specific estimates. Health Aff (Millwood) 28: w822–w831, 2009. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.5.w822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garland T Jr, Schutz H, Chappell MA, Keeney BK, Meek TH, Copes LE, Acosta W, Drenowatz C, Maciel RC, van Dijk G, Kotz CM, Eisenmann JC. The biological control of voluntary exercise, spontaneous physical activity and daily energy expenditure in relation to obesity: human and rodent perspectives. J Exp Biol 214: 206–229, 2011. doi: 10.1242/jeb.048397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief (288): 1–8, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harms MJ, Ishibashi J, Wang W, Lim HW, Goyama S, Sato T, Kurokawa M, Won KJ, Seale P. Prdm16 is required for the maintenance of brown adipocyte identity and function in adult mice. Cell Metab 19: 593–604, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Himms-Hagen J. Nonshivering thermogenesis. Brain Res Bull 12: 151–160, 1984. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(84)90183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hondares E, Iglesias R, Giralt A, Gonzalez FJ, Giralt M, Mampel T, Villarroya F. Thermogenic activation induces FGF21 expression and release in brown adipose tissue. J Biol Chem 286: 12983–12990, 2011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.215889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishibashi J, Seale P. Functions of Prdm16 in thermogenic fat cells. Temperature (Austin) 2: 65–72, 2015. doi: 10.4161/23328940.2014.974444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalinovich AV, de Jong JMA, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. UCP1 in adipose tissues: two steps to full browning. Biochimie 134: 127–137, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazak L, Chouchani ET, Jedrychowski MP, Erickson BK, Shinoda K, Cohen P, Vetrivelan R, Lu GZ, Laznik-Bogoslavski D, Hasenfuss SC, Kajimura S, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM. A creatine-driven substrate cycle enhances energy expenditure and thermogenesis in beige fat. Cell 163: 643–655, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kazak L, Chouchani ET, Lu GZ, Jedrychowski MP, Bare CJ, Mina AI, Kumari M, Zhang S, Vuckovic I, Laznik-Bogoslavski D, Dzeja P, Banks AS, Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. Genetic depletion of adipocyte creatine metabolism inhibits diet-induced thermogenesis and drives obesity. Cell Metab 26: 660–671.e3, 2017. [Erratum in Cell Metab 26: 693, 2017.] doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lark DS, Kwan JR, McClatchey PM, James MN, James FD, Lighton JRB, Lantier L, Wasserman DH. Reduced nonexercise activity attenuates negative energy balance in mice engaged in voluntary exercise. Diabetes 67: 831–840, 2018. doi: 10.2337/db17-1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee P, Linderman JD, Smith S, Brychta RJ, Wang J, Idelson C, Perron RM, Werner CD, Phan GQ, Kammula US, Kebebew E, Pacak K, Chen KY, Celi FS. Irisin and FGF21 are cold-induced endocrine activators of brown fat function in humans. Cell Metab 19: 302–309, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacLean PS, Higgins JA, Johnson GC, Fleming-Elder BK, Donahoo WT, Melanson EL, Hill JO. Enhanced metabolic efficiency contributes to weight regain after weight loss in obesity-prone rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R1306–R1315, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00463.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marlatt KL, Chen KY, Ravussin E. Is activation of human brown adipose tissue a viable target for weight management? Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 315: R479–R483, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00443.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin-Rodriguez E, Guillen-Grima F, Martí A, Brugos-Larumbe A. Comorbidity associated with obesity in a large population: The APNA study. Obes Res Clin Pract 9: 435–447, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.orcp.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melanson EL, Keadle SK, Donnelly JE, Braun B, King NA. Resistance to exercise-induced weight loss: compensatory behavioral adaptations. Med Sci Sports Exerc 45: 1600–1609, 2013. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31828ba942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peterson CM, Lecoultre V, Frost EA, Simmons J, Redman LM, Ravussin E. The thermogenic responses to overfeeding and cold are differentially regulated. Obesity (Silver Spring) 24: 96–101, 2016. doi: 10.1002/oby.21233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30a.R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2017. https://www.r-project.org/, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ravussin Y, Xiao C, Gavrilova O, Reitman ML. Effect of intermittent cold exposure on brown fat activation, obesity, and energy homeostasis in mice. PLoS One 9: e85876, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenbaum M, Hirsch J, Gallagher DA, Leibel RL. Long-term persistence of adaptive thermogenesis in subjects who have maintained a reduced body weight. Am J Clin Nutr 88: 906–912, 2008. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.4.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ. A role for brown adipose tissue in diet-induced thermogenesis. Nature 281: 31–35, 1979. doi: 10.1038/281031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, Kajimura S, Chin S, Kuang S, Scimè A, Devarakonda S, Conroe HM, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Rudnicki MA, Beier DR, Spiegelman BM. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature 454: 961–967, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nature07182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shabalina IG, Petrovic N, de Jong JM, Kalinovich AV, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. UCP1 in brite/beige adipose tissue mitochondria is functionally thermogenic. Cell Reports 5: 1196–1203, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steig AJ, Jackman MR, Giles ED, Higgins JA, Johnson GC, Mahan C, Melanson EL, Wyatt HR, Eckel RH, Hill JO, MacLean PS. Exercise reduces appetite and traffics excess nutrients away from energetically efficient pathways of lipid deposition during the early stages of weight regain. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R656–R667, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00212.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tagliaferro AR, Kertzer R, Davis JR, Janson C, Tse SK. Effects of exercise-training on the thermic effect of food and body fatness of adult women. Physiol Behav 38: 703–710, 1986. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90267-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas DM, Bouchard C, Church T, Slentz C, Kraus WE, Redman LM, Martin CK, Silva AM, Vossen M, Westerterp K, Heymsfield SB. Why do individuals not lose more weight from an exercise intervention at a defined dose? An energy balance analysis. Obes Rev 13: 835–847, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01012.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.U Din M, Saari T, Raiko J, Kudomi N, Maurer SF, Lahesmaa M, Fromme T, Amri EZ, Klingenspor M, Solin O, Nuutila P, Virtanen KA. Postprandial oxidative metabolism of human brown fat indicates thermogenesis. Cell Metab 28: 207–216.e3, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valenti G, Bonomi AG, Westerterp KR. Multicomponent Fitness Training Improves Walking Economy in Older Adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48: 1365–1370, 2016. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vallerand A, Schmegner I, Jacobs I. Influence of the Cold Buster ™ Sports Bar on Heat Debt, Mobilization and Oxidation of Energy Substrates. Ontario, Canada: Defence and Civil Inst of Environmental Medicine, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lichtenbelt W, Kingma B, van der Lans A, Schellen L. Cold exposure—an approach to increasing energy expenditure in humans. Trends Endocrinol Metab 25: 165–167, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Marken Lichtenbelt WD, Schrauwen P. Implications of nonshivering thermogenesis for energy balance regulation in humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R285–R296, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00652.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Essen G, Lindsund E, Cannon B, Nedergaard J. Adaptive facultative diet-induced thermogenesis in wild-type but not in UCP1-ablated mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 313: E515–E527, 2017. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00097.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vrieze A, Schopman JE, Admiraal WM, Soeters MR, Nieuwdorp M, Verberne HJ, Holleman F. Fasting and postprandial activity of brown adipose tissue in healthy men. J Nucl Med 53: 1407–1410, 2012. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.100701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Westerterp KR. Control of energy expenditure in humans. Eur J Clin Nutr 71: 340–344, 2017. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Westerterp KR, Meijer GA, Janssen EM, Saris WH, Ten Hoor F. Long-term effect of physical activity on energy balance and body composition. Br J Nutr 68: 21–30, 1992. doi: 10.1079/BJN19920063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weststrate JA, Hautvast JG. The effects of short-term carbohydrate overfeeding and prior exercise on resting metabolic rate and diet-induced thermogenesis. Metabolism 39: 1232–1239, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(90)90176-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wijers SLJ, Saris WH, van Marken Lichtenbelt WD. Individual thermogenic responses to mild cold and overfeeding are closely related. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92: 4299–4305, 2007. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wing RR, Phelan S. Long-term weight loss maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr 82, Suppl 1: 222S–225S, 2005. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.222S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoneshiro T, Aita S, Matsushita M, Kayahara T, Kameya T, Kawai Y, Iwanaga T, Saito M. Recruited brown adipose tissue as an antiobesity agent in humans. J Clin Invest 123: 3404–3408, 2013. doi: 10.1172/JCI67803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoo HS, Qiao L, Bosco C, Leong LH, Lytle N, Feng GS, Chi NW, Shao J. Intermittent cold exposure enhances fat accumulation in mice. PLoS One 9: e96432, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Young JB, Saville E, Rothwell NJ, Stock MJ, Landsberg L. Effect of diet and cold exposure on norepinephrine turnover in brown adipose tissue of the rat. J Clin Invest 69: 1061–1071, 1982. doi: 10.1172/JCI110541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Young JC, Treadway JL, Balon TW, Gavras HP, Ruderman NB. Prior exercise potentiates the thermic effect of a carbohydrate load. Metabolism 35: 1048–1053, 1986. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(86)90042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]