Abstract

Background

Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm) is one of the most common human parasitic helminths, and children are the most susceptible group. Some behavioral and environmental factors may facilitate pinworm infection. In the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), the status of pinworm infections among children remains unknown.

Methods

In Majuro City, there are 14 kindergartens with a total of 635 preschool children (PSC) whose age range of 5~6 years. The present investigation attempted to determine the pinworm prevalence and associated risk factors as well as investigate whether eggs contaminated the clothes of PSC or the ground and tables in classrooms of 14 kindergartens. Informed consent form and a self-administered questionnaire were given to parents prior to pinworm screening. Perianal specimens were collected by an adhesive scotch tape method, and clothing of belly and hip sites and the ground and tables of the classrooms were inspected using a cellophane tape method to detect any eggs contamination.

Results

In total, 392 PSC (5.28 ± 0.56 yrs. old) participated in this project. The overall prevalence of pinworm infection was 22.4% (88/392). Boys (24.5%) had higher prevalence than girls (20.31%) (p = 0.32). PSC aged > 5 years (32.77%) showed a significantly higher prevalence than those aged ≤5 years (17.95%) (p = 0.01). A univariate analysis indicated that PSC who lived in urban areas (22.95%) had a higher prevalence than those who lived in rural areas (20.69%) (p = 0.69). The employment status of the parents showed no association with the pinworm infection rate (p > 0.05). A logistic regression analysis indicated that “having an older sister” produced a higher risk of acquiring pinworm infection for PSC compared to those who did not have an older sister (OR = 2.02; 95%CI = 1.05~3.88; p = 0.04). No significant association between various other risk factors and pinworm infection was found (p > 0.05). Also, no eggs contamination was found on the clothes of the belly and hip sites or on the ground and tables in the 14 kindergartens.

Conclusions

Mass screening and treatment of infected PSC are important measures in pinworm control in the RMI.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12879-019-4159-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Enterobius vermicularis, Preschool children, Majuro City, Republic of Marshall Islands

Background

Enterobius vermicularis (pinworms) is one of the most common human parasitic helminths and by one estimation, about 200 million people worldwide are supposedly infected, with children aged 5~10 years old accounting for over 30% of cases [1].

Regardless of one’s particular socioeconomic level, race, or culture, pinworm infection can be facilitated by certain factors such as poor personal or group hygiene, and overcrowding in preschools, schools, orphanages, and family groupings [2, 3]. These conditions favor pinworm eggs transmission from person to person, directly via the anus-to-mouth route and finger contamination or indirectly by contaminated objects, e.g., toys, classroom tables, chairs, or the ground [2, 4]. Since personal hygiene and exposure are important transmission factors, preschool-aged children (PSC) who live in crowded environments such as kindergartens are the most common group susceptible to pinworm infection [2].

Adult males measure 2 to 5 mm, and the females measure 8 to 13 mm. The cecum of the large intestine is the major site for pinworms to live and the gravid female migrates at night to lay up to 15,000 eggs. Ingested eggs hatch in the duodenum, and larvae mature during their migration to the large intestine. In the absence of host autoinfection, infestation usually lasts only four to six weeks [1, 2]. In general, female worms release their eggs on the skin near the anus, and some eggs may detach from the perianal region and lodge on clothing, bedding, and other surfaces such as the ground or tables and chairs [2]; therefore, children may acquire an infection through ingestion of eggs-contaminated foods or inhalation of infective eggs in the dust or retrograde migration of hatched larvae from the anus to the intestines. This infection is more common in temperate than in tropical districts, although recent studies indicated that a prevalence of over 20% is not uncommon in many parts of the world [1, 3, 4].

Although pinworm infection may be symptomless in most patients, some of them may suffer perianal pruritus, insomnia, restlessness, and irritability, particularly children [1]. It should be stressed that pinworms may cause serious morbidity such as appendicitis and eosinophilic enterocolitis, and sometimes ectopic infections can result in pelvic inflammatory disease or urinary tract infections in females [2, 5, 6].

The appropriate diagnostic choice is to employ a cellophane tape test or scotch tape method for screening instead of stool examinations since eggs can be detected in only about 5% of fecal samples; in other words, the prevalence of pinworm infection is generally underestimated due to the difficulty of detecting pinworm eggs by stool examinations [7, 8]. Although effective treatment has been established for decades, the control of pinworm infection remains a challenge due to reinfection, incomplete treatment, and its characteristic of easy transmission [8].

In the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), the status of pinworm infection among children is supposedly high; nevertheless, until recently its exact prevalence has remained unknown. The country is situated in the Pacific Ocean, with a climate of high temperatures and moisture. The present investigation attempted to determine the prevalence of pinworm infection and associated risk factors by questionnaire interviews with the help of public health nurses. We also investigated whether eggs contaminated participants’ clothing or the ground and tables in kindergarten classrooms. This information will help establish baseline data for the Marshallese Ministry of Health (MOH) to enact effective measures against pinworm infection and transmission.

Methods

Geography of the Republic of the Marshall Islands and Majuro City

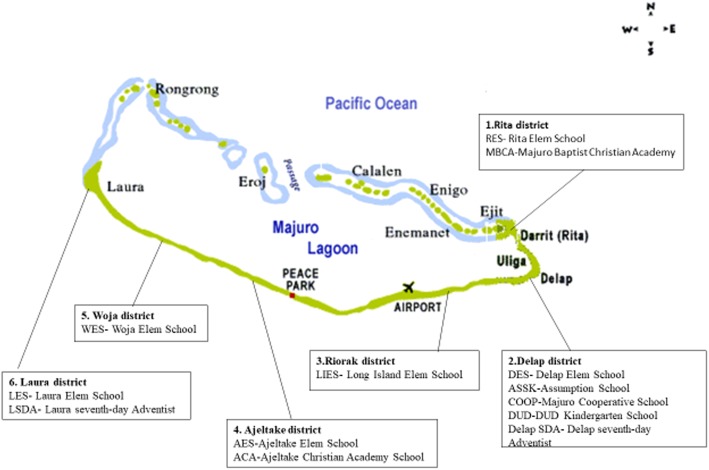

The RMI is an island nation situated in the central Pacific Ocean between 4° and 14°N latitude and 160° and 173°E longitude. Majuro Atoll, a large coral atoll of 64 islands, is a legislative district of the Ratak Chain of the RMI. Majuro Atoll has a land area of 3.7 mi2 and encloses a lagoon of 295 km2. The RMI has a total population of 52,560. The primary population center, named Majuro, is the capital and largest city in the RMI. Its characteristic climate is tropical, and the economy primarily relies on agriculture, fishery, and support from the United States. The major ethnic group is Micronesian [9]. This study was conducted in 14 kindergartens of six administrative areas in Majuro City according to suggestions by the MOH, RMI (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Map indicated the location of participant kindergartens at Majuro City, Republic of the Marshall Islands. Map is cited from the website: https://scottislandgrant.weebly.com/live.html

Study population and subject selection

This study was conducted from October 1 to 29, 2017. In Majuro City, there are 14 kindergartens in six administrative areas with a total of 635 PSC with an age range of 5~6 years. Prior to commencing the pinworm screening campaign, several explanatory meetings concerning the purpose of this screening project were held for parents and guardians. We also reminded them not to bathe their children on the morning of the collection day to avoid possible false-negative findings, and we distributed an informed consent form and a self-administered questionnaire to them. In addition to PSC, surfaces of tables and the ground in classroom were also examined for pinworm eggs contamination. Since no pilot study had previously been conducted for pinworm screening in the RMI, the sample size was determined using the general formula, n = z2p (1 − p)/d2 where, n is the sample size, z (1.96) is the standard deviation at a 95% confidence interval (CI), p is the prevalence (23%) based on the infection rate of intestinal parasites in the RMI from a previous study [10], and d is the allowed relative error (0.05) [11]. The minimum sample size from the calculation was 273 PSC.

Parasitological survey by employing the adhesive scotch tape and cellophane tape methods

In each participating child, a one specimen from the perianal site was collected by the adhesive scotch tape method, and two specimens including one from the belly and one from hip site of the clothing were collected by the cellophane tape method [1, 4]. In the meantime, the ground in the classroom was divided into nine collection sites (upper, middle, and lower parts of the left, middle, and right portions), and nine collections from each ground and 3~6 tables located on the ground in each kindergarten were also randomly inspected once per table using the cellophane tape method to detect any eggs contamination [4, 12].All of the specimen collected from kids, grounds and tables from each kindergarten were kept in the storage boxes and transported to medical laboratory of Majuro hospital immediately under room temperature and one qualified technician examined all of the specimen.

Questionnaire survey to determine risk factors of pinworm infection

A questionnaire was given to the parents or guardians of each child, asking about the child’s gender, the parents’ occupation, and family members. In addition, information concerning risk factors, including washing the hands before eating, washing the hands after using toilet facilities, finger sucking, fingernail trimming, the way and frequency of bathing, the type of floor, and the frequency of cleaning the bedding, was also obtained from participants [12].

Chemotherapy and follow-up

Infected children and their families were administered with a single dose of albendazole (200 mg/tablet) by public health nurses, MOH, RMI. A follow-up examination was conducted 2 weeks after chemotherapy by a medical technician in Laboratory Medicine, Majuro Hospital, RMI.

Statistical analysis

Differences in the prevalence of infection based on independent variables including gender, age group, residence, and parents’ employment status were determined by a Chi-squared (x2) test. The univariate crude odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were used to determine associations between independent variables, risk factors, and infection, and p values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses of data from the questionnaire and parasitological examination were conducted using SAS vers. 9.3 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shuang Ho Hospital, Taipei Medical University (TMU-JIRB no. N201708019), and they were also approved by the MOH, RMI. Informed consent form was obtained from participant parents/guardians to allow their kids to participate in this project. Meanwhile, participants were informed whether all of their data were permitted to consent for publication was also obtained in the informed consent.

Results

In Majuro City, there are 14 kindergartens in six administrative areas with a total of 635 PSC. In the present study, 392 PSC, with a mean age of 5.28 ± 0.56 years participated in this project for a participation rate of 61.7% (392/635). We found that 88 PSC had pinworm infection, giving an overall prevalence of 22.2% (88/392) (Table 1). Boys (24.5%, 49/200) had a slightly higher prevalence than girls (20.31%, 39/192) (p = 0.32) (Table 1). PSC aged > 5 years had a significantly higher prevalence (32.77%, 39/119) than that of PSC aged ≤5 years (17.95%, 49/273) (p = 0.01) (Table 1). A univariate analysis of the family background associated with pinworm infection indicated that PSC who lived in an urban area (Rita, Delap, or Riorak) (22.95%, 70/305) had a slightly higher prevalence than those who lived in a rural area (Ajeltake, Woja, or Laura) (20.69%, 18/87) (p = 0.69) (Table 1). Also, no significant relationship was found between the employment status of father or mother and the pinworm infection rate in children (p > 0.05) (Table 1). Interestingly, PSC who had an older sister (26.47%, 63/238) had a statistically higher prevalence than those who did not have an older sister (16.89%, 25/148) (p = 0.03) (Table 1). However, having an older or younger brother produced no significant difference in the prevalence of pinworm infection (p > 0.05) (Table 1). All demographic results are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of Enterobius vermicularis infection among preschool children from kindergartens in the capital area of the Republic of the Marshall Islands

| Variable | Enterobius vermicularis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive cases | Infection rate (%) | p valuea | |

| Gender | |||

| Female (N = 192) | 39 | 20.31 | 0.32 |

| Male (N = 200) | 49 | 24.50 | |

| Age | |||

| ≤ 5 years (N = 273) | 49 | 17.95 | 0.001a |

| > 5 years (N = 119) | 39 | 32.77 | |

| Urban residence | |||

| No (N = 87) | 18 | 20.69 | 0.65 |

| Yes (N = 305) | 70 | 22.95 | |

| Father employed | |||

| No (N = 57) | 12 | 21.05 | 0.69 |

| Yes (N = 312) | 73 | 23.40 | |

| Mother employed | |||

| No (N = 243) | 62 | 25.51 | 0.08 |

| Yes (N = 136) | 24 | 17.65 | |

| Have an older brother | |||

| No (N = 148) | 33 | 22.30 | 0.88 |

| Yes (N = 240) | 55 | 22.92 | |

| Have an older sister | |||

| No (N = 148) | 25 | 16.89 | 0.03a |

| Yes (N = 238) | 63 | 26.47 | |

| Have a younger brother | |||

| No (N = 197) | 46 | 23.35 | 0.69 |

| Yes (N = 189) | 41 | 21.69 | |

| Have a younger sister | |||

| No (N = 200) | 45 | 22.50 | 0.95 |

| Yes (N = 189) | 43 | 22.75 | |

a By Chi-square test

The logistic regression analysis further revealed that only the factor of having an older sister showed a higher risk of acquiring pinworm infection for PSC compared those who did not have an older sister (OR = 2.02; 95% CI = 1.05~3.88; p = 0.04) (Table 2). However, from the logistic regression analysis, we found no significant association between various variables and pinworm infection (p > 0.05) (Table 3). Also, we found no eggs contamination on the clothing of the belly or hip sites of each PSC by examining 784 cellophane tape-collected specimens as well as 182 cellophane tape-collected specimens from the ground and tables in 14 classrooms of the 14 kindergartens (data not shown).

Table 2.

Logistic regression analysis of Enterobius vermicularis infection among preschool children from kindergartens in the capital area of the Republic of the Marshall Islands

| Variable | Enterobius vermicularis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1.00 | 0.51 | |

| Male | 1.21 | 0.69~2.09 | |

| Age | |||

| ≤ 5 years | 1.00 | 0.08 | |

| > 5 years | 1.66 | 0.95~2.90 | |

| Urban residence | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.16 | |

| Yes | 1.65 | 0.82~3.32 | |

| Father employed | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.33 | |

| Yes | 1.43 | 0.64~3.19 | |

| Mother employed | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.23 | |

| Yes | 0.69 | 0.38~1.26 | |

| Have an older brother | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.38 | |

| Yes | 0.76 | 0.42~1.40 | |

| Have an older sister | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.04* | |

| Yes | 2.02 | 1.05~3.88 | |

| Have a younger brother | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.97 | |

| Yes | 0.99 | 0.56~1.74 | |

| Have a younger sister | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.71 | |

| Yes | 0.90 | 0.51~1.58 | |

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of risk-factors for Enterobius vermicularis infection among preschool children from kindergartens in the capital area of the Republic of the Marshall Islands

| Variable | Enterobius vermicularis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Washing hands before eating | |||

| Infrequent | 1.00 | 0.26 | |

| Frequent | 2.56 | 0.49~13.25 | |

| Washing hands after using toilet facilities | |||

| Infrequent | 1.00 | 0.42 | |

| Frequent | 0.53 | 0.11~2.49 | |

| Finger sucking | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.81 | |

| Yes | 0.89 | 0.35~2.29 | |

| Keeping the fingernails short | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.64 | |

| Yes | 0.88 | 0.51~1.52 | |

| Way of bathing | |||

| Showering | 1.00 | 0.89 | |

| Bathing in a tub | 1.05 | 0.52~2.15 | |

| Taking a bath after getting up | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.49 | |

| Yes | 1.60 | 0.41~6.24 | |

| Bathing with the help of family members | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.55 | |

| Yes | 0.78 | 0.35~1.74 | |

| Type of floor | |||

| Ground floor, single-family detached or townhouse | 1.00 | 0.33 | |

| Apartment | 0.59 | 0.20~1.73 | |

| Type of bed | |||

| Matting | 1.00 | 0.83 | |

| Wood or spring mattress | 1.07 | 0.60~1.91 | |

| Change bedding < 2 weeks | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.74 | |

| Yes | 1.45 | 0.16~13.59 | |

| Share a bedroom with family members | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.14 | |

| Yes | 0.59 | 0.29~1.19 | |

| Share a bed with family members | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.80 | |

| Yes | 1.09 | 0.57~2.07 | |

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Discussion

In general, the infection caused by E. vermicularis is relatively innocuous. Nevertheless, eggs deposition may cause perineal, perianal, and even vaginal irritation, and infected persons may try to relieve the irritation of the constant itching, possibly leading to potentially debilitating sleep disturbance, impaired concentration, emotional instability, or enuresis [3]. Furthermore, these uncomfortable symptoms can result in weight loss, urinary tract infections, and even acute or chronic appendicitis which can lead to death without appropriate surgical treatment [5, 6]. Therefore, children who exhibit perianal pruritus and nocturnal restlessness should be suspected of having pinworm infection [1, 3].

A previous study indicated that behavioral changes are frequently observed in pinworm-infected children who feel shameful and inferior due to having ‘worms’ [13]. However, children’s discomfort is often overlooked by parents, despite pinworm infection possibly causing developmental and/or health problems. In particular, mothers can become distraught when they think their child has been infected by ‘worms’ [3]. Therefore, treating pinworm infection can improve the quality of the child’s life, and campaigns and control measures to prevent pinworm are positively recognized by the majority of parents [4, 8].

Although adult worms directly seen by the naked eye and microscopic detection of eggs from feces allow a confirmative diagnosis, this is impractical, because adult worms are uncommonly seen around the anal area or in the stool, and eggs are only found in the stool of 5% of infected persons [1, 3]; thus, the scotch-tape test can serve as a quick and sensitive way to clinch a diagnosis [14].

In the present study, the overall prevalence of pinworm infection was 22.2% (88/392) in Marshallese PSC, and this infection rate is higher than those reported in Seoul, South Korea (9.5%, 113/1191) [8], Taipei, Taiwan (0.21%, 94/44163) [12], and Amol County, Iran (7.1%, 33/462) [15]; however, it was lower than rates seen in Cordobe Province, Argentina, where the prevalence of E. vermicularis in PSC was 43.4% [16], northern Thailand (25%) [17], and Timisoara, Romania (42.8%) [18].

The univariate analysis in the present study showed that the prevalence of pinworm infection was significantly higher in children aged > 5 years than in younger children aged ≤5 years, which agrees with results of other studies [8, 19]. This can be explained by play activity programs for children > 5 years old slightly differ from those of younger children aged ≤5 years, as they play outside at the kindergarten instead of taking a nap. Therefore, they have more opportunities to play with dirt and have greater frequency of physical contact with their friends than do younger children, thus they have a higher risk of acquiring pinworm infection. Although no significant difference was found in prevalences by gender, the rate in boys was slightly higher. These findings were similar to those reported previously [20–22] and it may be explained by gender differences in children, as girls having better personal hygienic habits than boys, thus protecting them from pinworm infection.

Interestingly, we found that children with an older sister had a significantly higher prevalence. This finding was also similar to that reported in Taiwan [12], indicating that transmission of the infection might occur in the family through school-aged siblings, particularly if an older sister is tasked with caring for younger sisters and brothers. Thus, in the RMI, an older sister might play an important role in transmitting pinworm eggs to her younger siblings.

Substantial studies have indicated that parents’ occupation is an important indicator of the socioeconomic status of the children; however, in the present study, the parents having or not having a job was not related to the opportunity for pinworm infection in PSC, although the occupation of the parents was also reported to be a risk factor for infection [4, 7, 8, 23].

It was reported that inadequate personal hygiene might increase the risk of pinworm infection among children, and significant factors associated with pinworm infection include playing on the floor, nail biting, failing to wash hands before meals, and living in non-apartment dwellings [24]. However, personal hygiene factors, such as finger sucking, keeping the fingernails short, the frequency and way of bathing, etc., were not found to be significantly associated with pinworm infection for Marshallese PSC in the present study. Although sharing a bed/bedroom with family members and the floor type were previously reported to be important risk factors in pinworm transmission [25], in the present study, we did not find such an association with pinworm infection. It was reported that environmental factors are important in the transmission of pinworm [4, 12, 25]. In our study, we did not find pinworm eggs contamination on tables or the ground in the classrooms or on the belly and hip sites of clothing from the children from the 14 participating kindergartens. This indicates that tables, the ground, and the children’s clothing might not be important transmission source for Marshallese PSC.

Conclusion

Taken together, mass screening should continue, and infected PSC and their family members should be treated, both of which are important measures for controlling pinworm infection in the RMI.

Additional file

Anonymous original data for statistical analysis. (XLSX 83 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mr. Chamberlin for critical revision and editing of our manuscript.

Abbreviations

- CI

Confidence interval

- MOH

Ministry of Health

- OR

Odds ratio

- PSC

Preschool-aged children

- RMI

Republic of the Marshall Islands

- x2

Chi-squared test

Authors’ contributions

C-KF, M-SW, KB, and J-WL conceived the study, participated in the design of the study, coordination, and drafted the manuscript. T-WC performed the statistical analysis. C-KF, Y-CH, A-WY, Y-TH, RK, S-LH, C-YT, C-MC, and Y-TW carried out the screening, questionnaire interview, and examination of specimens. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the financial support by Shuang Ho Hospital, Taipei Medical University (TMU-JIRB no. N201708019). They do not involve any project design, performing and manuscript preparation.

Availability of data and materials

All of the original data has been appended in Additional file 1.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shuang Ho Hospital, Taipei Medical University (TMU-JIRB no. N201708019), and they were also approved by the MOH, RMI. Informed consent form was obtained from participant parents /guardians to allow their kids to participate in this project. Meanwhile, participants were informed whether all of their data were permitted to consent for publication was also obtained in the informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chia-Kwung Fan, Phone: +886-2-27395092, Email: tedfan@tmu.edu.tw.

Ting-Wu Chuang, Email: chtingwu@tmu.edu.tw.

Ying-Chieh Huang, Email: hsica2526@tmu.edu.tw.

Ai-Wen Yin, Email: arielaiwen@gmail.com.

Chia-Mei Chou, Email: maychou@tmu.edu.tw.

Yu-Ting Hsu, Email: 12274@s.tmu.edu.tw.

Ramson Kios, Email: sike23.kios@gmail.com.

Shao-Lun Hsu, Email: arinahsu@gmail.com.

Ying-Ting Wang, Email: marshallthc@gmail.com.

Mai-Szu Wu, Email: maiszuwu@gmail.com.

Jia-Wei Lin, Email: ns246@tmu.edu.tw.

Kennar Briand, Email: k.briand123@yahoo.com.

Chia-Ying Tu, Email: 15263@s.tmu.edu.tw.

References

- 1.Kucik CJ, Martin GL, Sortor BV. Common intestinal parasites. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1161–1168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG. Assessment of frequency, transmission, and genitourinary complications of enterobiasis (pinworms) Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:837–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook GC. Enterobius vermicularis infection. Gut. 1994;35:1159–1162. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.9.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim DH, Cho MK, Park MK, Kang SA, Kim BY, Park SK, Yu HS. Environmental factors related to enterobiasis in a southeast region of Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2013;51:139–142. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2013.51.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsai CY, Junod R, Jacot-Guillarmod M, Beniere C, Ziadi S, Bongieggsnni M. Vaginal Enterobius vermicularis diagnosed on liquid-based cytology during Papanicolaou test cervical cancer screening: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2018;46:179–186. doi: 10.1002/dc.23812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Altun E, Avci V, Azatcam M. Parasitic infestation in appendicitis. A retrospective analysis of 660 patients and brief literature review. Saudi Med J. 2017;38:314–318. doi: 10.15537/smj.2017.3.18061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kubiak K, Dzika E, Paukszto L. Enterobiasis epidemiology and molecular characterization of Enterobius vermicularis in healthy children in North-Eastern Poland. Helminthologia. 2017;54:284–291. doi: 10.1515/helm-2017-0042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song HJ, Cho CH, Kim JS, Choi MH, Hong ST. Prevalence and risk factors for enterobiasis among preschool children in a metropolitan city in Korea. Parasitol Res. 2003;91:46–50. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0836-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ichiho HM, deBrum I, Kedi S, Langidrik J, Aitaoto N. An assessment of noncommunicable diseases, diabetes, and related risk factors in the Republic of the Marshall Islands, Majuro atoll: a systems perspective. Hawaii J Med Public Health. 2013;72:87–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao CW, Chuang TW, Huang YC, Chou CM, Chiang CL, Lee FP, Hsu YT, Lin JW, Briand K, Tu CY, Fan CK. Intestinal parasitic infections: current prevalence and risk factors among schoolchildren in capital area of the republic of Marshall Islands. Acta Trop. 2017;176:242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutterford C, Copas A, Eldridge S. Methods for sample size determination in cluster randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:1051–1067. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen KY, Yen CM, Hwang KP, Wang LC. Enterobius vermicularis infection and its risk factors among pre-school children in Taipei, Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2018;51:559–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2016.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell LJ. The pinworm, Enterobius vermicularis. Prim Care. 1991;18:13–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan PC. Review of enterobiasis in Taiwan and offshore islands. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 1998;31:203–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Afrakhteh N, Marhaba Z, Mahdavi SA, Garoosian S, Mirnezhad R, Vakili ME, Shahraj HA, Javadian B, Rezaei R, Moosazadeh M. Prevalence of Enterobius vermicularis amongst kindergartens and preschool children in Mazandaran Province, north of Iran. J Parasit Dis. 2016;40:1332–1336. doi: 10.1007/s12639-015-0683-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guignard SAH, Freye L. Prevalence of enterobiosis in the children of Cordobe province. Eur J Epidemiol. 2000;16:287–293. doi: 10.1023/A:1007651714790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bunchu N, Vitta A, Thongwat D, Lamlertthon S, Pimolsri U, Waree P, Wongwigkarn J, Khamsri B, Cheewapat R, Wichai S. Enterobius vermicularis infection among children in lower northern Thailand. J Trop Med Parasitol. 2011;34:36–40. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neghina R, Neghina AM, Marincu I, Iacobiciu I. Intestinal nematode infections in Romania: an epidemiological study and brief review of literature. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2011;11:1145–1149. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2010.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang S, Yao Z, Hou Y, Wang D, Zhang H, Ma J, Zhang L, Liu S. Prevalence of Enterobius vermicularis among preschool children in 2003 and 2013 in Xinxiang city, Henan province, Central China. Parasite. 2016;23:30. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2016030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang TK, Liao CW, Huang YC, Chang CC, Chou CM, Tsay HC, Huang A, Guu SF, Kao TC, Fan CK. Prevalence of Enterobius vermicularis infection among preschool children in kindergartens of Taipei City, Taiwan in 2008. Korean J Parasitol. 2009;47:185–187. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2009.47.2.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang IS, Kim DH, An HG, Son HM, Cho MK, Park MK, Kang SA, Kim BY, Yu HS. Impact of health education on the prevalence of enterobiasis in Korean preschool students. Acta Trop. 2012;122:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hussien SM, Taha MA, Omran EK. Relationship between Enterobius vermicularis infection and pelvic inflammatory diseases in children at Sohag governorate, Egypt. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2015;45:633–638. doi: 10.12816/0017931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee SE, Lee JH, Ju JW, Lee WJ, Cho SH. Prevalence of Enterobius vermicularis among preschool children in Gimhae-si, Gyeongsangnam-do, Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2011;49:183–185. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2011.49.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sung JF, Lin RS, Huang KC, Wang SY, Lu YJ. Pinworm control and risk factors of pinworm infection among primary-school children in Taiwan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;65:558–562. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.65.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pai HH, Chen ER. A study of multiple factors related to Enterobius infection among pre-schoolchildren. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 1988;4:217–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Anonymous original data for statistical analysis. (XLSX 83 kb)

Data Availability Statement

All of the original data has been appended in Additional file 1.