Abstract

A novel series of imidazoisoindoles were identified as potent indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) inhibitors. Lead optimization toward improving potency and eliminating CYP inhibition resulted in the discovery of lead compound 25, a highly potent IDO inhibitor with favorable pharmacokinetic properties. In the MC38 xenograft model in hPD-1 transgenic mice, 25 in combination with the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody (SHR-1210) achieved a synergistic antitumor effect superior to each single agent.

Keywords: IDO, immuno-oncology, SAR, lead optimization

The immune system plays a vital role in the regulation of tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. Immune checkpoint inhibitors that restore the capability of the immune system to recognize and eliminate malignant cells have produced impressive clinical benefit, but many patients across a wide range of malignancies still do not respond.1 These findings imply that there are additional immunoregulators that maintain productive immunosurveillance in cancer. Indeed, tumor cells escape immune elimination through evolving various tactics to evade, subvert, and manipulate innate and adaptive immunity. As a result, combinatory regimens with different targeted therapeutic agents are necessary to produce sustained a therapeutic effect.2,3 One of these agents is a family of tryptophan catabolizing enzymes including indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), which convert tryptophan first to N-formylkynurenine and further to kynurenine and additional metabolites. Both the depletion of tryptophan and the signals generated by its metabolites are important contributors to immunosuppresion.4−6

Expression of IDO is widespread in human body, being most abundant in antigen-presenting cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells. IDO activity is increased in several tumor types and is correlated with a poor prognosis.7,8 TDO is exclusively produced in the liver to maintain the systemic tryptophan levels in response to food uptake. Although the major role of IDO in immune regulation has been validated, there is recent evidence that suggest TDO might regulate immunosuppression similar to that of IDO.9 IDO selective and IDO/TDO dual inhibitors have been the focus of research,10−13 whereas TDO selective inhibitors remain elusive.9,14

Tumor cells hijack the immunosuppressive process by up-regulating IDO activity in the tumor microenvironment, which leads to accelerated differentiation of CD4+ T cells into regulatory T cells, as well as suppression of CD8+ effector T cells and impaired dendritic cell functions. Moreover, tumor cells evade immune-mediated eradication via PD-L1 expression because the interaction of PD-L1 with PD-1 inhibits the secretion of cytotoxic mediators by CD8+ T cells. In addition, IDO was further up-regulated upon blocking PD-1/PD-L1 interaction in mice due to compensatory mechanism.15 Therefore, the simultaneous blockade of both pathways may represent an opportunity to accomplish greater antitumor effects by the complementary regulation of the cytotoxic T cells.

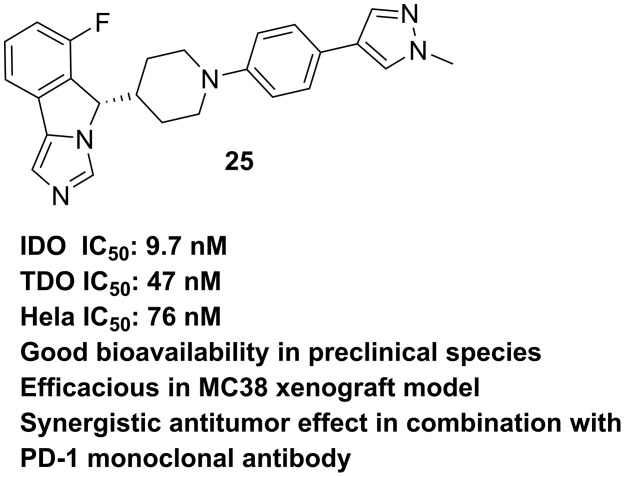

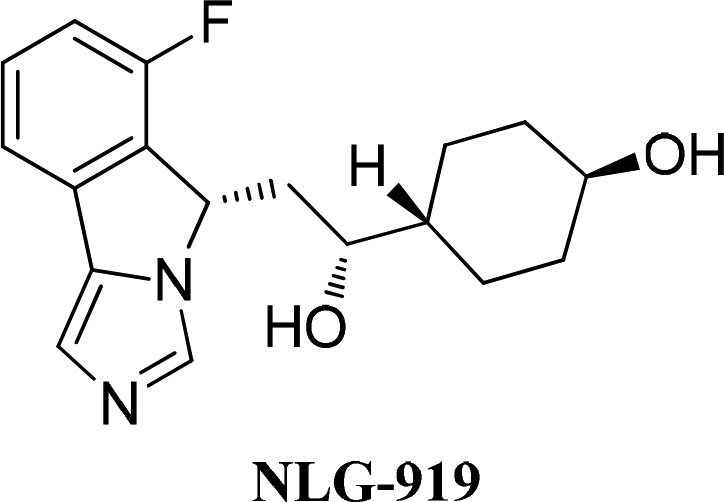

NLG-919 (Figure 1) is one of the IDO/TDO dual inhibitors that have been evaluated in clinical trials alone or in combination with anti-PD-L1 antibody for various solid tumors.16−18 Herein, we report the synthesis and SAR study of a novel series of imidazoisoindoles as potent IDO inhibitors and the identification of lead compound that synergized with PD-1 blockade in a murine tumor model.

Figure 1.

Imidazoleisoindole derivative as IDO inhibitor in clinical trial.

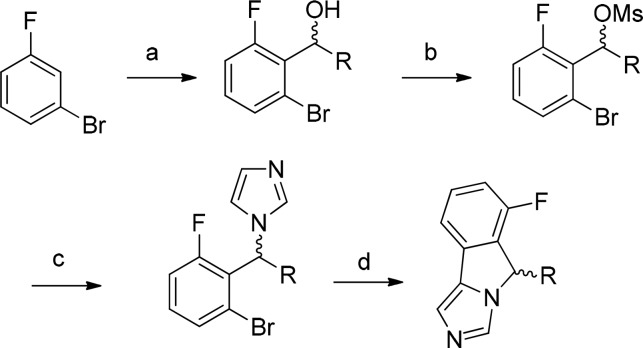

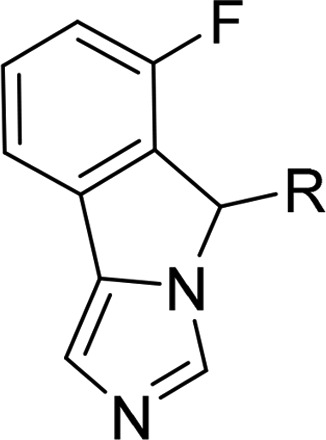

NLG-919 interacts with IDO via imidazoleisoindole core coordinating to the iron center of heme. The hydroxyl group on the side chain engages in an extensive hydrogen bond network and contributes to the biological activity.19 However, three consecutive chiral centers exert tremendous structural complexities and synthetic challenges. We hypothesized that modification of the side chain of NLG-919 with the imidazoleisoindole core kept intact could offer the best opportunity to fine-tune potency and physicochemical properties. Compounds 1–8 were synthesized via the route shown in Scheme 1.20 The regioselective lithiation of m-bromofluorobenzene with LDA followed by nucleophilic addition to a variety of substituted aldehydes gave rise to corresponding alcohols. The resulting alcohols were mesylated and subsequently substituted by imidazole. The final intramolecular Pd-mediated cyclization furnished the tricyclic imidazoleisoindole core decorated with various appendages.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 5-Substituted Imidazoleisoindoles.

Reagents and conditions: (a) (1) LDA, THF, −78 °C, 1 h; (2) RCHO, −78 °C, 1 h; (b) NaH, THF, MsCl, reflux, 48 h; (c) imidazole, NaH, DMF, 100 °C, 12 h; (d) Pd(OAc)2, PPh3, Cy2NMe, DMF, 100 °C, 5 h.

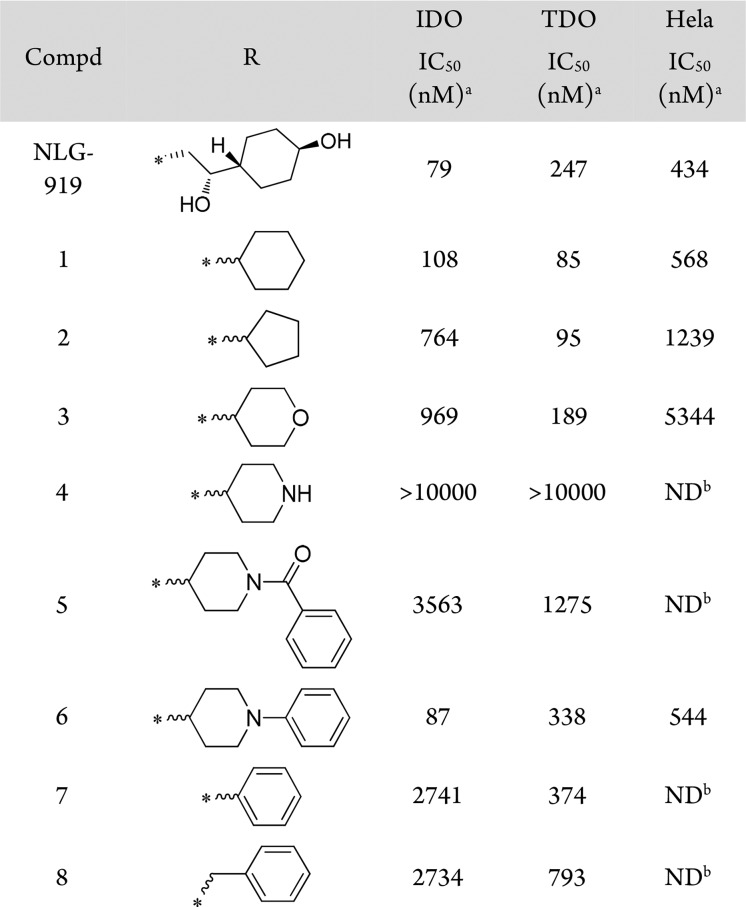

The screening assays include enzymatic assays with purified recombinant human IDO/TDO proteins and cellular IDO inhibition assay in the Hela cell line. Cyclohexyl 1 exhibited comparable potency to NLG-919, as shown in Table 1. However, smaller cyclopentyl 2 was less potent in IDO assay. Tetrahydropyranyl 3 was a much weaker inhibitor compared to the all-carbon counterpart 1. Piperidinyl 4 completely lost potency in all the assays because the hydrogen bond donor at this position may not be tolerated. Blocking NH with amide (5) did not improve potency. To our delight, phenylpiperidinyl 6 restored the potency similar to NLG-919. The replacement of cyclohexyl (1) with phenyl (7) led to a 20-fold drop of potency in the enzymatic assays. Benzyl 8 showed similar potency to phenyl 7.

Table 1. SAR of 5-Substituted Imidazoleisoindoles.

Values are expressed as the mean of three independent determinations.

ND: not determined.

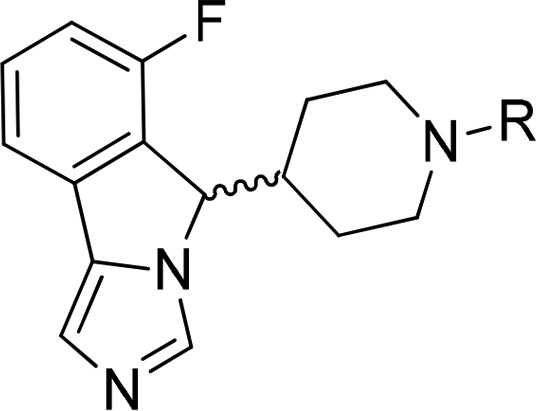

Compound 6 was selected as the start for the next round SAR study. A series of substituted piperidinyls were synthesized and assessed (Table 2). To lower lipophilicity of compound 6, replacement of the phenyl group with heteroaryls was investigated. Heteroaryls such as thiadiazole (9), indole (10), and benzothiazole (11) demonstrated enhanced potency toward IDO enzymatic assay but not cellular assay. Simple substituents such as fluorine (12) and cyano (13) did not improve potency. The morpholine 14 showed 3-fold lower potency than 6. Replacement of morpholine with pyridine (15) resulted in a 10-fold boost toward IDO activity. Among the aromatic substitutions tested, methylpyrazole 18 was the most potent in all three assays (IDO IC50 = 26 nM, TDO IC50 = 132 nM, and Hela IC50 = 101 nM, respectively). The m-substituted methylpyrazole 17 was 2-fold less potent than 18 due to unfavorable orientation of the aromatic substitution. Fluorine (19 and 20) and methyl (21 and 22) were tolerated on the central phenyl ring. Fluorine 20 was 2-fold more potent than 18. Fluorine 19 and methyl 21 showed comparable potency to 18. In compound 23, central phenyl ring was replaced by pyrimidine and the potency decreased 4-fold compared to 18.

Table 2. SAR of 5-Piperidinyl-Substituted Imidazoleisoindoles.

Values are expressed as the mean of three independent determinations.

NLG-919 was reported as a potent inhibitor of CYP3A4 (IC50 = 2.8 uM).21 Consequently, CYP inhibition assay was included at this stage of lead optimization. As shown in Table 3, substitutions on the central phenyl ring inevitably led to inhibition of different CYP isoforms. The most potent compound 20 significantly inhibited CYP3A4 (IC50 = 2.6 uM). Compound 18 had a clean CYP profile with only moderate inhibition of CYP3A4.

Table 3. CYP Inhibition of Compounds 18–21.

| compound | 1A2 IC50 (uM)a | 2C9 IC50 (uM)a | 2C19 IC50 (uM)a | 2D6 IC50 (uM)a | 3A4 IC50 (uM)a m/tb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | 8.4/6.08 |

| 19 | 8.95 | 0.94 | 1.15 | 9.61 | 0.35/0.95 |

| 20 | >10 | 7.4 | 6.81 | >10 | 4.57/2.6 |

| 21 | >10 | 0.3 | 1.57 | 4.51 | 0.21/0.44 |

Values are expressed as the mean of three independent determinations.

Midazolam as substrate/testosterone as substrate.

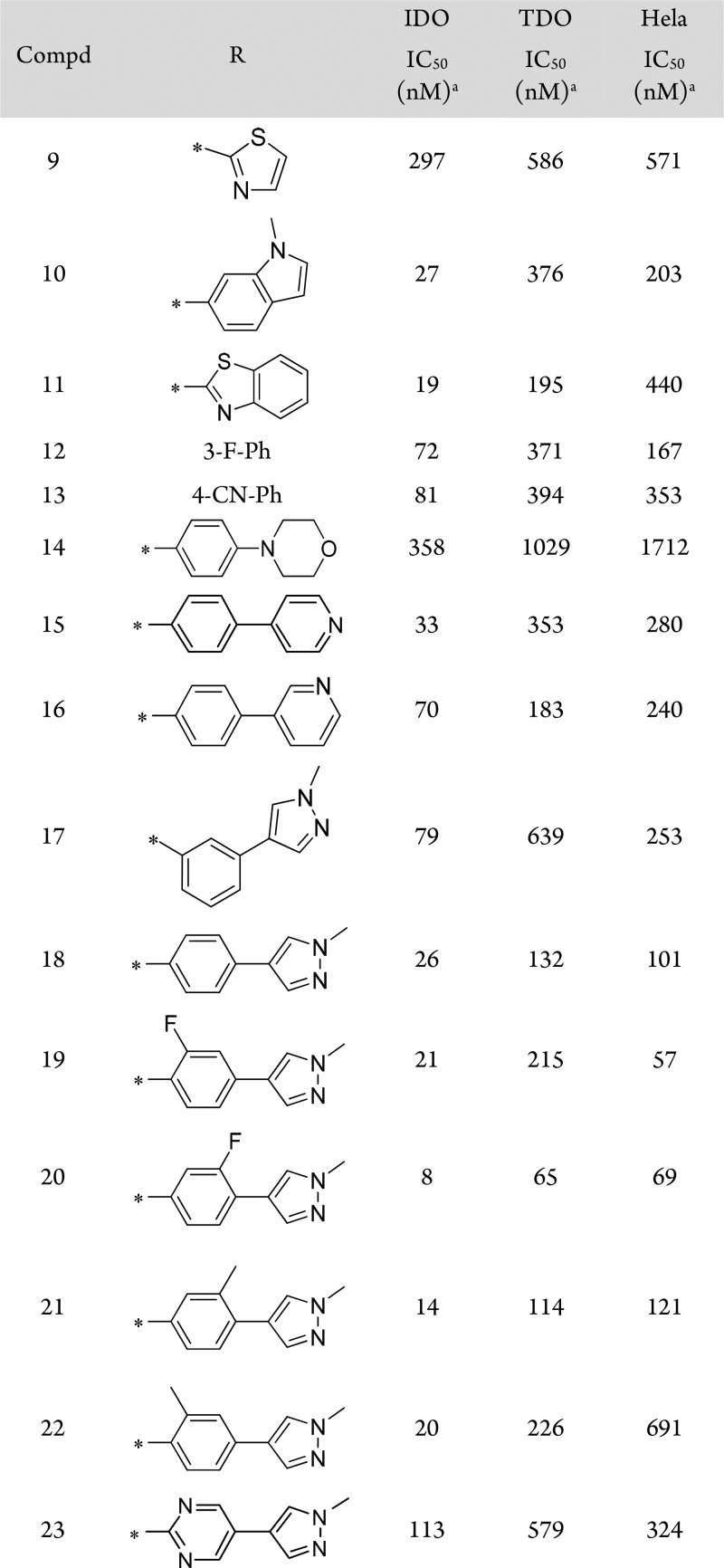

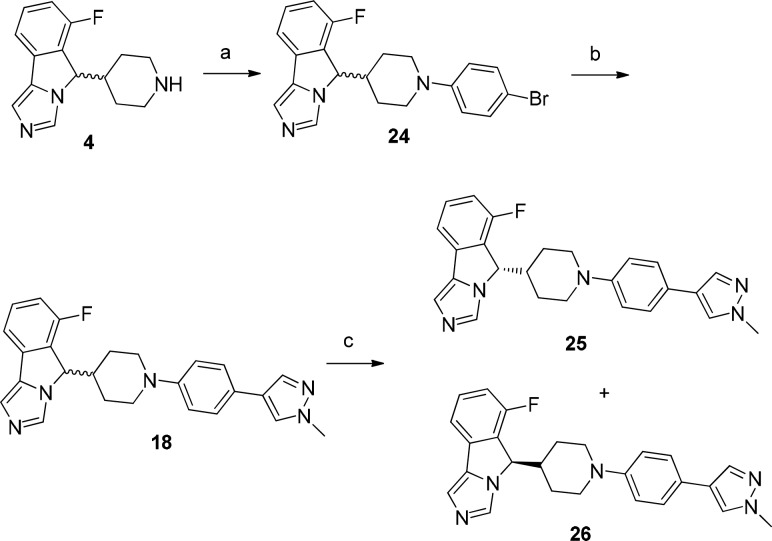

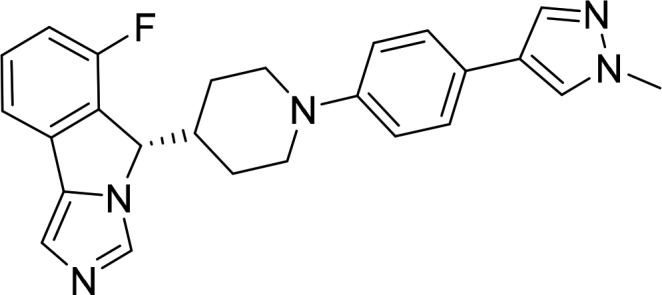

Lead compound 18 was synthesized by the route shown in Scheme 2. Chiral separation of the racemate 18 gave rise to the desired enantiomer 25, while another enantiomer 26 was totally inactive in all IDO assays (IC50 > 10 μM).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Lead Compound 25.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 1,4-dibromobenzene, Pd2(dba)3, BINAP, tBuONa, toluene, 80 °C, 12 h; (b) 1-methyl-4-(4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolan-2-yl)-1H-pyrazole, Pd(dppf)Cl2, Na2CO3, DME/H2O, microwave, 120 °C, 40 min; (c) chiral separation.

Compound 25 was fully profiled in vitro and in vivo, as shown in Table 4. It was a highly potent dual IDO/TDO inhibitor in both enzymatic assays and cellular assays. It was clean in in vitro toxicity studies, including CYP and hERG. It showed high plasma protein bonding in mouse, dog, and human samples and high liver microsome stability in rat and human samples. Pharmacokinetic profiling of 25 in mouse, rat, and dog samples demonstrated good oral exposure and bioavailability (F = 59.6%, 60.3%, and 27.3%, respectively) in all species.

Table 4. Profiling of Compound 25.

| enzymatic IDO IC50 (nM)a | 9.7 |

| enzymatic TDO IC50 (nM)a | 47 |

| cellular Hela IC50 (nM)a | 76 |

| CYP inhibition (1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4) | >30 uM |

| hERG | >30 uM |

| PPB (mouse/dog/human) | 99.6%/99.2%/99.7% |

| liver microsome stability (rat/human) T1/2 (min) | 142/147 |

| mouse PK@10 mg/kg | |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 3605 |

| AUC (ng/mL × h) | 29116 |

| t1/2 (h) | 4.55 |

| bioavailability (F%) | 59.6% |

| rat PK@10 mg/kg | |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 1848 |

| AUC (ng/mL× h) | 6133 |

| t1/2 (h) | 1.22 |

| bioavailability (F%) | 60.3% |

| dog PK@2 mg/kg | |

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 166 |

| AUC (ng/mL × h) | 1340 |

| t1/2 (h) | 6.49 |

| bioavailability (F%) | 27.3% |

Values are expressed as the mean of three independent determinations.

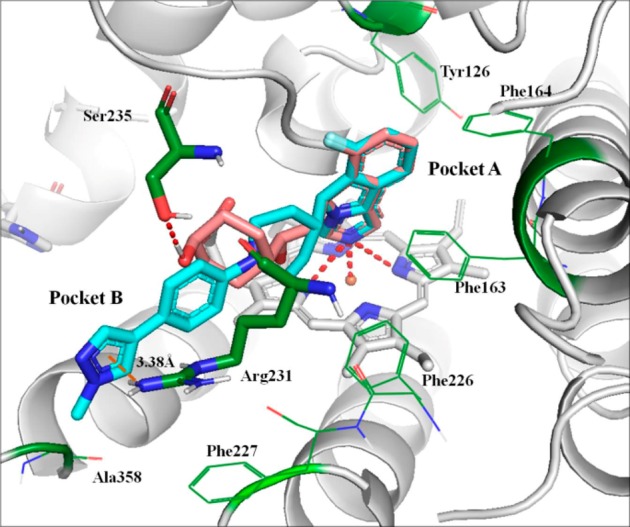

To gain insight into the superior potency of 25, computational study was performed. As shown in Figure 2, 25 coordinated to the iron center of heme in a similar manner to NLG-919, while the side chain of 25 stuck deeper into pocket B. The methylpyrazol ring engaged in a cation−π interaction with Arg231 with a distance of 3.38 Å. Cation−π interactions are ubiquitously found in proteins, protein–ligand, and protein–DNA complexes and impose influence on biological structures, molecular recognition, and catalysis.22 Due to the additional cation−π interaction, 25 served as a more potent inhibitor despite the lack of the hydroxyl group, which formed a hydrogen bonding with Ser235 as in NLG-919.

Figure 2.

Molecular docking of 25 (cyan) binding to the IDO active site (PDB code: 2D0T). NLG-919 (salmon) and 25 are superimposed for comparison. The key cation−π interaction is indicated by the brown dashed line.

Based on the promising in vitro activity and pharmacokinetic data, 25 was further evaluated in the in vivo pharmacodynamic study. A single dose of 100 mg/kg of 25 was administrated orally to C57 mice. The maximum kynurenine reduction by 57% was observed at 2 h after dosing (see Figure S1).

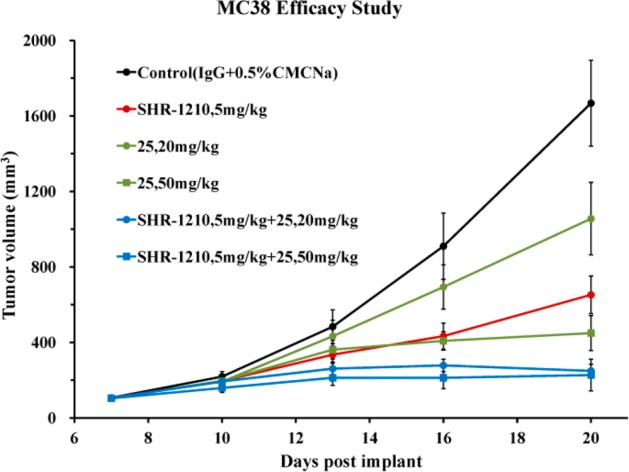

The hPD-1 transgenic mice implanted with MC38 tumors were treated with 25 to evaluate the antitumor efficacy. As shown in Figure 3, oral treatment with 25 (bid ×14) demonstrated dose-dependent tumor growth inhibition (20 mg/kg, TGI = 39%; 50 mg/kg, TGI = 78%). The anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody SHR-1210 was only modestly efficacious in this tumor model (5 mg/kg, ip, qod ×8, TGI = 65%).23 Compound 25 was dosed in combination with SHR-1210 using the following schedule: SHR-1210, 5 mg/kg, ip, qod ×8; 25, 20 or 50 mg/kg, po, bid ×14. The combination regimen at both dose levels achieved significantly enhanced antitumor activity (TGI > 90%) compared to either treatment alone. It was noted that no body weight loss was observed for all of the treatment groups.

Figure 3.

Efficacy study of 25 alone and in combination with SHR-1210 in the MC38 xenograft model in hPD-1 transgenic mice.

In summary, a highly potent IDO inhibitor 25 with favorable preclinical toxicity and pharmacokinetic properties was discovered through several rounds of SAR studies with the aim of improving potency and eliminating CYP inhibition liabilities. Compound 25 proved to be orally efficacious in the MC38 xenograft model and its combination with anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody showed a synergistic antitumor effect.

Acknowledgments

We thank analytical group, DMPK group of the company for their contributions.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- PD-1

programmed death 1

- PD-L1

programmed death-ligand 1

- LDA

lithium diisopropylamide

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- DME

1,2-dimethoxyethane

- TEA

triethylamine

- MsCl

methanesulfonyl chloride

- DMF

dimethylformamide

- BINAP

2,2′-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1′-binaphthyl

- dba

dibenzylideneacetone

- SAR

structure and activity relationship

- CYP

cytochrome p450 enzyme

- hERG

human ether-a-go-go-related gene

- PPB

plasma protein bonding

- PK

pharmacokinetic

- po

orally

- ip

intraperitoneally

- bid

twice daily

- qod

every other day

- TGI

tumor growth inhibition.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00114.

Biological assays, pharmacokinetic assays, an in vivo pharmacodynamic study, an in vivo efficacy study, computational methods, experimental procedures, and analytical data for key compounds (PDF)

Author Present Address

∥ Janssen R&D Center, Jinchuang Mansion, 4560 Jinke Road, Shanghai 201210, China

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Hoos A. Development of immuno-oncology drugs - from CTLA4 to PD1 to the next generations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2016, 15, 235–247. 10.1038/nrd.2015.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams J. L.; Smothers J.; Srinivasan R.; Hoos A. Big opportunities for small molecules in immuno-oncology. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2015, 14, 603–622. 10.1038/nrd4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toogood P. L. Small molecule immuno-oncology therapeutic agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 319–329. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platten M.; Wick W.; Van den Eynde B. J. Tryptophan catabolism in cancer: beyond IDO and tryptophan depletion. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 5435–5440. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platten M.; von Knebel Doeberitz N.; Oezen I.; Wick W.; Ochs K. Cancer immunotherapy by targeting IDO1/TDO and their downstream effectors. Front. Immunol. 2015, 5, 673. 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Baren N.; Van den Eynde B. J. Tryptophan-degrading enzymes in tumoral immune resistance. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 34. 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godin-Ethier J.; Hanafi L.-A.; Piccirillo C. A.; Lapointe R. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression in human cancers: clinical and immunologic perspectives. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 6985–6991. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opitz C. A.; Litzenburger U. M.; Sahm F.; Ott M.; Tritschler I.; Trump S.; Schumacher T.; Jestaedt L.; Schrenk D.; Weller M.; Jugold M.; Guillemin G. J.; Miller C. L.; Lutz C.; Radlwimmer B.; Lehmann I.; von Deimling A.; Wick W.; Platten M. An endogenous tumour-promoting ligand of the human aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Nature 2011, 478, 197–203. 10.1038/nature10491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilotte L.; Larrieu P.; Stroobant V.; Colau D.; Dolusic E.; Frédérick R.; De Plaen E.; Uyttenhove C.; Wouters J.; Masereel B.; Van den Eynde B. J. Reversal of tumoral immune resistance by inhibition of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 2497–2502. 10.1073/pnas.1113873109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast G. C.; Malachowski W. P.; DuHadaway J. B.; Muller A. J. Discovery of IDO1 inhibitors: from bench to bedside. Cancer Res. 2017, 77, 6795–6811. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Röhrig U. F.; Majjigapu S. R.; Vogel P.; Zoete V.; Michielin O. Challenges in the Discovery of Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 9421–9437. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue E. W.; Sparks R.; Polam P.; Modi D.; Douty B.; Wayland B.; Glass B.; Takvorian A.; Glenn J.; Zhu W.; Bower M.; Liu X.; Leffet L.; Wang Q.; Bowman K. J.; Hansbury M. J.; Wei M.; Li Y.; Wynn R.; Burn T. C.; Koblish H. K.; Fridman J. S.; Emm T.; Scherle P. A.; Metcalf B.; Combs A. P. INCB24360 (epacadostat), a highly potent and selective indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) inhibitor for immuno-oncology. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 8, 486–491. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.6b00391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosignani S.; Bingham P.; Bottemanne P.; Cannelle H.; Cauwenberghs S.; Cordonnier M.; Dalvie D.; Deroose F.; Feng J. L.; Gomes B.; Greasley S.; Kaiser P. E.; Kraus M.; Négrerie M.; Maegley K.; Miller N.; Murray B. W.; Schneider M.; Soloweij J.; Stewart A. E.; Tumang J.; Torti V. R.; Van den Eynde B.; Wythes M. Discovery of a novel and selective indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase(IDO-1) inhibitor 3-(5-fluoro-1H-indol-3-yl)pyrrolidine-2,5-dione (EOS200271/PF-06840003) and its characterization as a potential clinical candidate. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 9617–9629. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei Z.; Mendonca R.; Gazzard L.; Pastor R.; Goon L.; Gustafson A.; VanderPorten E.; Hatzivassiliou G.; Dement K.; Cass R.; Yuen P.-w.; Zhang Y.; Wu G.; Lin X.; Liu Y.; Sellers B. D. Aminoisoxazoles as potent inhibitors of tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase 2 (TDO2). ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 417–421. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spranger S.; Koblish H. K.; Horton B.; Scherle P. A.; Newton R.; Gajewski T. F. Mechanism of tumor rejection with doublets of CTLA-4, PD-1/PD-L1, or IDO blockade involves restored IL-2 production and proliferation of CD8+ T cells directly within the tumor microenvironment. J. Immunother. Cancer 2014, 2, 3. 10.1186/2051-1426-2-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak-Kapoor A.; Hao Z.; Sadek R.; Dobbins R.; Marshall L.; Vahanian N. N.; Ramsey W. J.; Kennedy E.; Mautino M. R.; Link C. J.; Lin R. S.; Royer-Joo S.; Liang X.; Salphati L.; Morrissey K. M.; Mahrus S.; McCall B.; Pirzkall A.; Munn D. H.; Janik J. E.; Khleif S. N. Phase Ia study of the indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) inhibitor navoximod (GDC-0919) in patients with recurrent advanced solid tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2018, 6, 61. 10.1186/s40425-018-0351-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCT02471846: A study of GDC-0919 and atezolizumab combination treatment in participants with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors. https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02471846?term=NCT02471846&rank=1 (accessed May 20, 2019).

- Spahn J.; Peng J.; Lorenzana E.; Kan D.; Hunsaker T.; Segal E.; Mautino M.; Brincks E.; Pirzkall A.; Kelley S.; Mahrus S.; Liu L.; et al. Improved anti-tumor immunity and efficacy upon combination of the IDO1 inhibitor GDC-0919 with anti-PD-l1 blockade versus anti-PD-l1 alone in preclinical tumor models. J. Immunother. Cancer 2015, 3, 303. [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y.-H.; Ueng S.-H.; Tseng C.-T.; Hung M.-S.; Song J.-S.; Wu J.-S.; Liao F.-Y.; Fan Y.-S.; Wu M.-H.; Hsiao W.-C.; Hsueh C.-C.; Lin S.-Y.; Cheng C.-Y.; Tu C.-H.; Lee L.-C.; Cheng M.-F.; Shia K.-S.; Shih C.; Wu S.-Y. Important hydrogen bond networks in indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) inhibitor design revealed by crystal structures of imidazoleisoindole derivatives with IDO1. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 282–93. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mautino M.; Kumar S.; Waldo J.; Jaipuri F.; Kesharwani T.. Fused imidazole derivatives useful as IDO inhibitors. PCT Patent WO 2012142237, Oct 18, 2012.

- Mautino M. R.; Jaipuri F. A.; Waldo J.; Kumar S.; Adams J.; Van Allen C.; Marcinowicz-Flick A.; Munn D. H.; Vahanian N. N.; Link C. J. NLG919, a novel indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO)-pathway inhibitor drug candidate for cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2013, 73, 491. 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2013-491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar K.; Woo S. M.; Siu T.; Cortopassi W. A.; Duarte F.; Paton R. S. Cation−π interactions in protein–ligand binding: theory and data-mining reveal different roles for lysine and arginine. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 2655–2665. 10.1039/C7SC04905F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Zhao Y.; Tebben A. J.; Sheriff S.; Ruzanov M.; Fereshteh M. P.; Fan Y.; Lippy J.; Swanson J.; Ho C.-P.; Wautlet B. S.; Rose A.; Parrish K.; Yang Z.; Donnell A. F.; Zhang L.; Fink B. E.; Vite G. D.; Augustine-Rauch K.; Fargnoli J.; Borzilleri R. M. Discovery of 4-azaindole inhibitors of TGFβRI as immuno-oncology agents. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 1117–1122. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.8b00357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.