Abstract

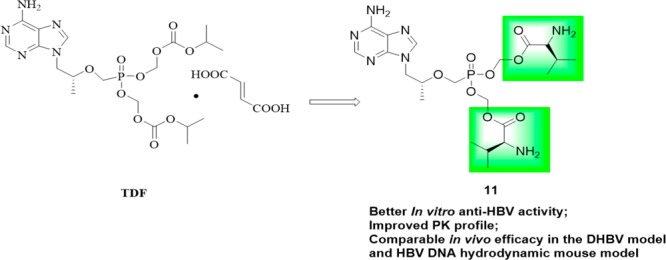

A series of bis(l-amino acid) ester prodrugs of tenofovir (TFV) were designed and synthesized as new anti-HBV agents in this work. Four compounds 11, 12a, 12d, and 13b displayed better anti-HBV activity (IC50: 0.71–4.22 μM) than the parent drug TFV. The most active compound 11 (IC50: 0.71 μM), a bis(l-valine) ester prodrug of TFV, was found to have obviously greater AUC0–∞,Cmax, and F% than tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), and potent in vivo efficacy which is not inferior to TDF in a duck HBV (DHBV) model and a HBV DNA hydrodynamic mouse model, and it may serve as a promising lead compound for further anti-HBV drug discovery.

Keywords: Tenofovir, anti-HBV activity, l-amino acid, prodrugs

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a major public health problem. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated over 250 million people are chronically infected with HBV currently. About one-quarter of these individuals will be likely to develop serious liver diseases such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The end stage of liver diseases caused by HBV infection claims the lives of approximately 700,000 patients annually.1 Current therapies include nucleos(t)ide analogues [lamivudine (3TC), adefovir, tenofovir (TFV), and entecavir (ETV), etc.] and interferons (IFNs). Unfortunately, neither of them can result in a high rate of clinical cure, which is defined as the loss of HBV surface antigen (HBsAg).2,3 As such, there are huge unmet medical needs to discover and develop novel agents with differentiated mechanisms of action.4,5 Several such candidates are currently in clinical trials, but none of them has been approved by the FDA.6 Therefore, a more practical approach seems to modify the structures of existing drugs to increase safety and potency.

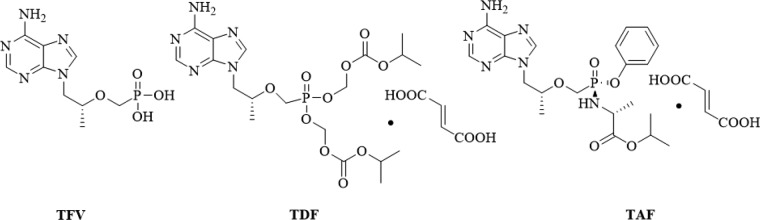

Tenofovir (TFV, Figure 1), an acyclic nucleoside, displays potent antiviral activity against HBV,7 HIV,8 and HSV-29 but nephrotoxicity and poor bioavailability.10 Several lipid prodrug strategies of TFV have been developed for this purpose and were extensively reviewed.11 As the first prodrug of TFV, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF, Figure 1) manufactured by Gilead Sciences, has been widely used in treating HBV infection, but it was reported to induce lactic acidosis, Fanconi syndrome, acute renal failure, and bone loss.12,13 Although newly approved tenofovir-alafenamide (TAF, Figure 1) shows little to no nephrotoxicity and more potent antiviral activity than TDF at 1/10 the dose,14 the high cost limits its widespread use.

Figure 1.

Structures of tenofovir (TFV) and its prodrugs TDF and TAF.

We are impressed by l-amino-acid based prodrug esters such as the antiviral agents valacyclovir and valganciclovir, both of which significantly improve antiviral activity and oral bioavailability of the corresponding parent drugs acyclovir and ganciclovir, respectively.15,16 This property was ascribed to their advantages of being able to be efficiently delivered via the hPEPT1.17,18 To the best of our knowledge, none of such l-amino acid ester prodrug strategies have been reported in the case of TFV phosphonates. Initially, therefore, we intended to design and synthesize a series of novel bis(l-amino acid) ester prodrugs of TFV as anti-HBV agents in this work. Our primary objective was to find promising prodrugs with improved bioavailability and anti-HBV activity compared to TDF, to facilitate the further development of these compounds.

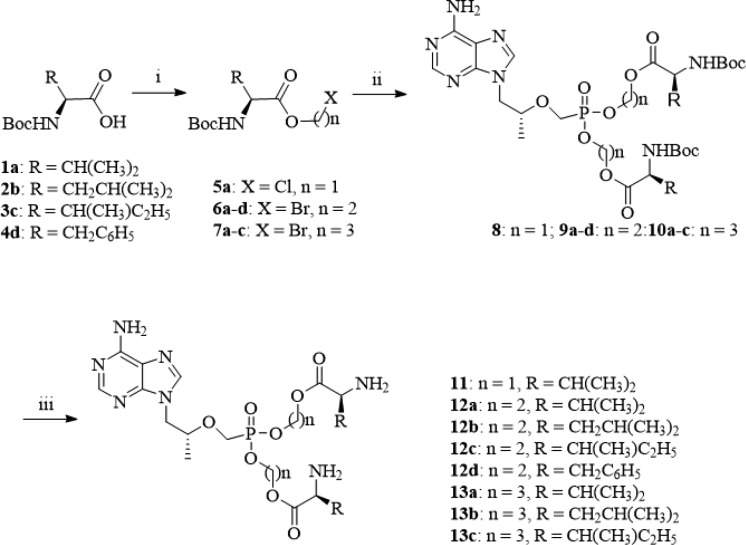

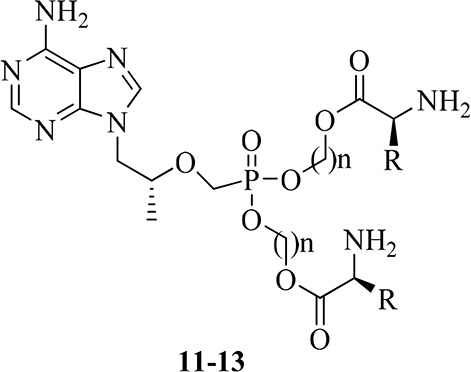

Detailed synthetic pathways to target compounds 11–13 are shown below in Scheme 1. According to known procedures,19−21 condensation of N-Boc-protected l-amino acids 1–4 with chloromethyl chlorosulfate using n-Bu4NHSO4 as a phase transfer catalyst (PTC) gave chloromethyl ester (5), or with 2-bromoethanol and 3-bromoporpan-1-ol yielded 2-bromoethyl and 3-bromopropyl esters (6a–d, 7a–c), respectively, in the presence of dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP). The resulting esters (5–7) were then coupled with TFV using N,N′-dicyclohexyl-4-morpholine carboxamidine (DCMC) as an acid scavenger in dimethylformamide (DMF) to give intermediates 8–10. The target compounds 11–13 were obtained by removal of the Boc-protecting group of the corresponding 8–10 in hydrochloride-1,4-dioxane solution.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Target Compounds 11–13.

Reagents and conditions: (i) n = 1, chloromethyl chlorosulfate, n-Bu4NHSO4, NaHCO3, CH2Cl2–H2O, rt, 5 h, 71%; n = 2 or 3,2-bromoethanol/3-bromoporpan-1-ol, DCC, DMAP, CH2Cl2, rt, 12 h, 79.3%; (ii) TFV, DCMC, DMF, 80 °C, 2.5 h, microwave, 25%–51%; (iii) HCl (g), dioxane solution, rt, 0.5 h, 81–90%.

The synthesized compounds 11–13 were initially screened for an in vitro inhibitory effect on the replication of HBV in HepG2.2.15 cell lines according to ref (22). The IC50, CC50, and SI values of them along with TFV, TDF, and 3TC for comparison are presented in Table 1. Four target compounds 11, 12a, 12d, and 13b displayed more potent anti-HBV activity (IC50: 0.71–4.22 μM) than the parent drug TFV (IC50: 15.98 μM). Among them, compound 11 (IC50: 0.71 μM) was roughly comparable to TDF (IC50: 0.85 μM), and 3 and 22 times more potent than lamivudine (IC50: 2.22 μM) and TFV, respectively. The SI value of compound 11 was about 3 times higher than those of TFV and TDF. On the other hand, all of the bis(l-amino acid) ester prodrugs 11–13 possessed significantly reduced cell toxicity compared with that of TDF. In general, anti-HBV activity and cell toxicity of these prodrugs are related to kinds of the l-amino acids and length of the carbon chain linker (n), although the structure–activity relationship (SAR) is difficult to summarize.

Table 1. In Vitro Anti-HBV Activity of Bis(l-amino acid) Ester Prodrugs 11–13 of TFV.

| Compd.a | n | R | IC50b (μM) | CC50c (μM) | SId |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 1 | Isopropyl | 0.71 ± 0.23 | 57.28 ± 0.00 | 80 |

| 12a | 2 | Isopropyl | 2.60 ± 0.21 | 217.93 ± 0.00 | 84 |

| 12b | 2 | 2-Methylpropyl | >12.98 | 217.93 ± 0.00 | |

| 12c | 2 | 1-Methylpropyl | 12.23 ± 7.40 | 293.83 ± 0.00 | 24 |

| 12d | 2 | Benzyl | 2.93 ± 0.27 | 315.12 ± 68.72 | 97 |

| 13a | 3 | Isopropyl | >3.24 | 51.94 ± 69.97 | |

| 13b | 3 | 2-Methylpropyl | 4.22 ± 1.22 | 217.93 ± 0.00 | 47 |

| 13c | 3 | 1-Methylpropyl | >49.62 | 315.12 ± 120.89 | |

| TFV | 15.95 ± 7.36 | 435.22 ± 127.48 | 27 | ||

| TDF | 0.85 ± 0.34 | 20.71 ± 6.64 | 24 | ||

| Lamivudine | 2.22 ± 0.34 | >218.10 | >98 |

Obtained as hydrochloride salts.

IC50: 50% inhibitory concentration of cytoplasmic HBV-DNA synthesis.

CC50: 50% cytotoxic concentration on HepG2.2.15 cells.

SI: selective index (CC50/IC50). The cytotoxicity of compounds on HepG2.2.15 cells was assayed by the CPE (cytopathic effect) method. Both CC50 and IC50 were determined by the Reed and Muench method. Each experiment was performed at least twice separately. TFV: Tenofovir; TDF: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; 3TC: lamivudine.

The most active compound, 11, was further evaluated for its in vivo pharmacokinetic (PK) profiles in SD rats, following a single oral dose administration, in comparison with the parent TFV and prodrug TDF. For TFV the oral dose was calculated to be 20 mg/kg (0.07 mmol/kg) while the intravenous injection was 5 mg/kg. Considering that both 11 and TDF quickly undergo hydrolysis to TFV, we compared the PK parameters of TFV obtained after oral administrations of equimolar (0.07 mmol/kg) 11, TFV, and TDF. As shown in Table 2, compound 11 displayed the shortest T1/2 of 1.30 h, but significantly greater AUC0–∞ of 6524 h·ng/mL and Cmax of 2882 ng/mL than both TFV and TDF. More importantly, the oral bioavailability (F, 10.30%) of 11 was found to be about 7 and 3 times TFV and TDF, respectively. These results indicated that compound 11 had promising PK properties to support in vivo efficacy studies in animal models.

Table 2. Pharmacokinetics Properties of 11 in SD Ratsa.

| Compd. | Route | Dose (mg·kg–1) | Cl (mL·kg–1·min–1) | T1/2 (h) | Tmax (h) | Cmax (ng·mL–1) | AUC0–∞ (h·ng·mL–1) | F (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TFV | IV | 5 | 5.35 | 10.2 | 15779 | |||

| PO | 20 | 3.56 | 0.833 | 207 | 888 | 1.41 | ||

| TDF | PO | 44.3 | 6.14 | 0.25 | 699 | 2148 | 3.40 | |

| 11 | PO | 45.5 | 1.30 | 0.582 | 2882 | 6524 | 10.3 |

Mean value (n = 3 per group).

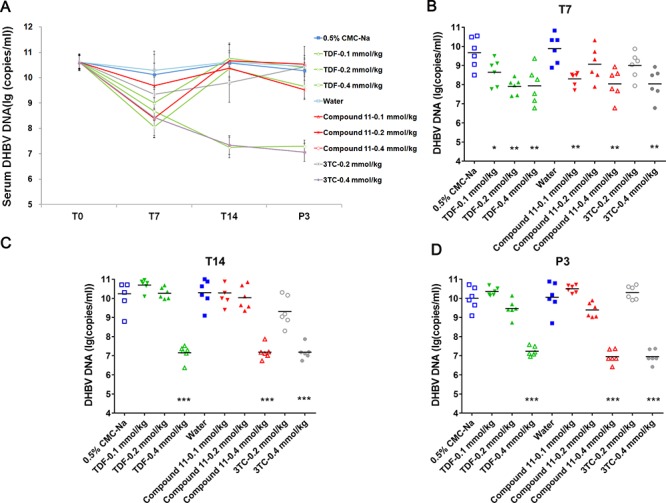

To determine whether compound 11 shows an antiviral effect in vivo, DHBV-infected ducks were first treated with 0.1, 0.2, or 0.4 mmol/Kg of compound 11 orally. Blood samples were collected at day 0 (before treatment, T0), 7 (T7), and 14 (T14) treatment and at day 3 after the termination of treatment (P3) to quantify DHBV DNA. No statistically significant weight change during treatment was observed (data not shown). As negative controls, the serum DHBV DNA level in the normal ducks was less than 100 IU/mL (data not shown). There were also no statistically significant differences of serum DHBV DNA level between the two vehicle controls [0.5% CMC-Na (sodium carboxyl methyl cellulose) and water] at each time point (Figure 2). The serum DHBV DNA in ducks treated with 0.4 mmol/kg of 3TC was significantly reduced. Except at T7, both compound 11 and TDF treatment induced a dose-dependent reduction of serum DHBV DNA up to 3.2 log10 compared to vehicle controls (Figure 2). Noticeably, the reduction level of the serum DHBV DNA in ducks treated with compound 11 was similar to that treated with TDF at the same dose and treatment time. These data demonstrate that oral administration of compound 11 results in a potent anti-HBV activity in a duck HBV model.

Figure 2.

In vivo antiviral activity of compound 11 in a duck HBV model.

DHBV-infected ducks were treated with three doses of TDF or compound 11 at 0.1 mmol/kg, 0.2 mmol/kg, and 0.4 mmol/kg or the vehicle via oral gavage twice-daily. 3TC was administered orally once-daily. Six ducks were included in each group. (A) Blood was collected on 0 (T0, before treatment), 7 (T7), and 14 (T14) days posttreatment and 3 days after treatment cessation (P3), and serum DHBV DNA was extracted and analyzed by a real-time PCR assay. Mean values ± SD are plotted for each group. (B, C, D) DHBV DNA in serum on days T7 (B), T14 (C), and P3 (D) of DHBV-infected ducks with various doses of TDF or compound 11. 3TC treatment serves as positive controls. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05 (compared with the vehicle control).

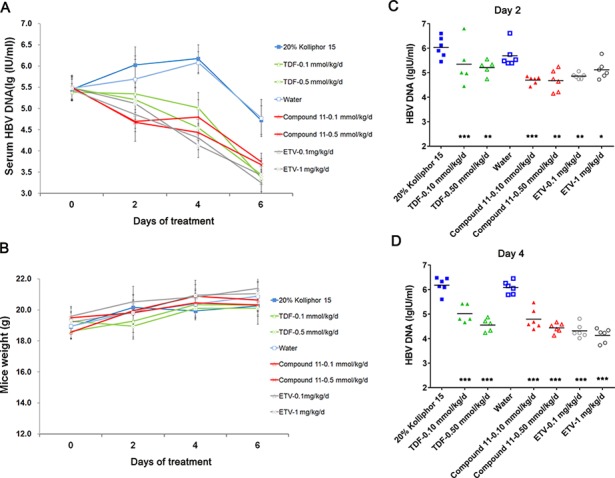

To further determine whether compound 11 effectively exerts an antiviral effect in mice, C57BL/6 mice were hydrodynamically injected with an HBV 1.3mer plasmid to establish HBV replication in mice hepatocytes. As shown in Figure 3B, no significant weight change was observed during treatment. Five mice injected with PBS through the tail vein without compound treatment were included as negative controls, and the serum HBV DNA level was less than 100 IU/mL (data not shown). A significant reduction in serum HBV DNA was observed in animals treated with ETV. There was no statistically significant difference of serum HBV DNA between the 20% Kolliphor HS 15 treatment group and the water group. The twice daily oral administration of compound 11 resulted in reduction in serum HBV DNA in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3). The 4-day treatment of compound 11 and TDF either at the dose of 0.10 mmol/Kg/d or at 0.50 mmol/Kg/d produced a similar reduction of approximate 1.1 and 1.7 log 10, respectively, in serum HBV DNA (Figure 3D). However, the groups treated with these two dosing groups of compound 11 at 2 day posttreatment performed better than the TDF-treated groups (Figure 3C) although this was only statistically significant (P < 0.05) for the group treated with 0.50 mmol/Kg/d of compound 11. In summary, compound 11 also exerts a potent antiviral activity in a HBV DNA hydrodynamic mouse model.

Figure 3.

In vivo antiviral activity of compound 11 in a HBV hydrodynamic mouse model.

One day after hydrodynamic injection of HBV 1.3mer plasmid (day 0), mice were treated with three doses of TDF or compound 11 at 0.10 mmol/Kg/d, and 0.50 mmol/Kg/d of the vehicle via oral gavage twice-daily. ETV was administered orally once-daily (n = 5–6 per group). (A) Blood was collected at 0, 2, 4, and 6 days posttreatment, and serum HBV DNA was extracted and analyzed by a real-time PCR assay. Mean values ± SD are plotted for each group. (B) The mice body weight during 6 days of treatment. (C, D) HBV DNA in serum on day 2 (C) and 4 (D) of HBV hydrodynamic injection mice with various doses of TDF or compound 11. ETV treatment serves as positive controls. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05 (compared with the vehicle control).

In summary, a series of bis(l-amino acid) ester prodrugs of TFV were designed and synthesized as new anti-HBV agents. Four compounds 11, 12a, 12d, and 13b displayed more potent anti-HBV activity (IC50: 0.71–4.22 μM) than the parent drug TFV. Especially, the most active compound, 11 (IC50: 0.71 μM), with improving SI, a bis(l-valine) ester prodrug of TFV, was found to show excellent PK properties and potent in vivo efficacy in the DHBV model and HBV DNA hydrodynamic mouse model, and it may serve as a promising lead compound for further anti-HBV drug discovery. Studies to determine the in vivo efficacy of 11 in an adeno-associated virus-mediated mouse HBV replication model are ongoing in our lab.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Cl

clearance

- Cmax

maximum serum concentration

- Tmax

time to maximum concentration

- AUC0–∞

area under curve from time zero to infinity

- t1/2

plasma elimination half-life

- F

oral bioavailability

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00184.

Experimental procedures and analytical data of the synthesized compounds (PDF)

Author Contributions

∥ A.W. and S.W. contributed equally. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The work was financially supported by CAMS Initiative for Innovative Medicine CAMS-2018-I2M-3-004, National Mega-project for Innovative Drugs (2018ZX09711001-007-002), National Science and Technology Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2018ZX09101003-003-003), and Science Fund for Creative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81621064).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

This paper published ASAP on May 23, 2019 with errors in the text and in Figures 2 and 3. The corrected paper was reposted on June 13, 2019.

Supplementary Material

References

- WHO . Hepatitis B: World Health Organization Fact Sheet 204.http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs204/en/ (accessed Jan 17, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- Papatheodoridis G.; Buti M.; Cornberg M.; Janssen H.; Mutimer D.; Pol S.; Raimondo G. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J. Hepatol. 2012, 57, 167–185. 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Zhu W.; Tang G.; Mayweg A. V.; Yang G.; Wu J. Z.; Shen H. C. Novel therapeutics in discovery and development for treatment of chronic HBV infection. Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 2013, 48, 265–281. 10.1016/B978-0-12-417150-3.00017-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang L.; Zhao Q.; Wu S.; Cheng J.; Chang J.; Guo J. T. The current status and future directions of hepatitis B antiviral drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery 2017, 12, 5–15. 10.1080/17460441.2017.1255195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testoni B.; Durantel D.; Zoulim F. Novel targets for hepatitis B virus therapy. Liver Int. 2017, 37, 33–39. 10.1111/liv.13307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S.; Gao L.; Han X.; Hu T.; Hu X.; Liu H.; Thomas A. W.; Yan Z.; Yang S.; Young J.; Yun H.; Zhu W.; Shen H. Discovery of Small Molecule Therapeutics for Treatment of Chronic HBV Infection. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4, 257–277. 10.1021/acsinfecdis.7b00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney W. E.; Ray A. S.; Yang H.; Qi X.; Xiong S.; Zhu Y.; Miller M. D. Intracellular Metabolism and in Vitro Activity of Tenofovir against Hepatitis B Virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2471–2477. 10.1128/AAC.00138-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant J. E.; DeJesus E.; Arribas J. R.; Pozniak A. L.; Gazzard B. Tenofovir Df, Emtricitabine, and Efavirenz Vs. Zidovudine, Lamivudine, and Efavirenz for Hiv. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 354, 251–260. 10.1056/NEJMoa051871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrei G.; Lisco A.; Vanpouille C.; Introini A.; Balestra E.; et al. Topical Tenofovir, a Microbicide Effective against Hiv, Inhibits Herpes Simplex Virus-2 Replication. Cell Host Microbe 2011, 10, 379–389. 10.1016/j.chom.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giesler K. E.; Marengo J.; Liotta D. C. Reduction Sensitive Lipid Conjugates of Tenofovir: Synthesis, Stability, and Antiviral Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 7097–7110. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradere U.; Garnier-Amblard E. C.; Coats S. J.; Amblard F.; Schinazi R. F. Synthesis of Nucleoside Phosphate and Phosphonate Prodrugs. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9154–9218. 10.1021/cr5002035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis W.; Day B. J.; Copeland W. C. Mitochondrial Toxicity of Nrti Antiviral Drugs: An Integrated Cellular Perspective. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2003, 2, 812–822. 10.1038/nrd1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlitz L. C.; Ohan M. S.; Stokes M. B.; Radhakrishnan J.; D’Agati V. D.; Markowitz G. S. Tenofovir Nephrotoxicity: Acute Tubular Necrosis with Distinctive Clinical, Pathological, and Mitochondrial Abnormalities. Kidney Int. 2010, 78, 1171–1177. 10.1038/ki.2010.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruane P. J.; DeJesus E.; Berger D.; et al. Antiviral Activity, Safety, and Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics of Tenofovir Alafenamide as 10-Day Monotherapy in Hiv-1-Positive Adults. JAIDS, J. Acquired Immune Defic. Syndr. 2013, 63, 449–455. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182965d45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrichsen G. M.; Chen W.; Begtrup M.; Lee C. P.; Smith P. L.; Borchardt R. T. Synthesis of analogs of L-valacyclovir and determination of their substrate activity for the oligopeptide transporter in Caco-2 cells. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2002, 16, 1–13. 10.1016/S0928-0987(02)00047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara M.; Hung W.; Fei Y.; Leibach V. G.; Ganapathy M. E. Transport of Valganciclovir, a Ganciclovir Prodrug, via Peptide Transporters PEPT1 and PEPT2. J. Pharm. Sci. 2000, 89, 781–789. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen C. U.; Brodin B.; Jørgensen F. S.; Frokjaer S.; Steffansen B. Human peptide transporters: therapeutic applications. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2002, 12, 1329–1350. 10.1517/13543776.12.9.1329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio-Aliaga I.; Daniel H. Mammalian peptide transporters as targets for drug delivery. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2002, 23, 434. 10.1016/S0165-6147(02)02072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X.; Jiang S.; Li C.; Xin J.; Yang Y.; Ji R. Design and synthesis of novel bis(L-amino acid) ester prodrugs of 9-[2-(phosphonomethoxy)ethyl]adenine (PMEA) with improved anti-HBV activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 465–470. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilon C.; Klausner Y. A novel method for the facile synthesis of depsipeptides. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979, 20, 3811–3814. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)95531-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harada N.; Hongu M.; Tanaka T.; Kawaguchi T.; Hashiyama T.; Tsujihara K. A Simple Preparation of Chloromethyl Esters of the Blocked Amino Acids. Synth. Commun. 1994, 24, 767–772. 10.1080/00397919408011298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sells M. A.; Chen M. L.; Acs G. Production of hepatitis B virus particles in Hep G2 cells transfected with cloned hepatitis B virus DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1987, 84, 1005–1009. 10.1073/pnas.84.4.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.