Abstract

Quinoline derivatives have extensively been used for both pharmaceutical agents and bioimaging. However, typical synthesis of quinoline derivatives is generally through strong acid/base-catalyzed or metal-catalyzed methods at high temperatures. Here we report a catalyst-free synthesis of 2,4-disubstituted 7-aminoquinolines with high selectivity and good yields via the introduction of a trifluoromethyl group. It is discovered that quinolines containing both amino and trifluoromethyl groups exhibit strong intramolecular charge-transfer fluorescence with large Stokes shifts. We further applied the obtained quinolines to live-cell imaging and found that some of the derivatives can target specifically Golgi apparatus in various cell lines (HeLa, U2OS, and 4T1 cells) in vitro and the colocalization with commercial Golgi marker is retained during the mitosis in HeLa cells. Moreover, the quinoline dyes can also be used for Golgi apparatus imaging with two-photon fluorescence microscopy. These results provide new insights into developing low cost Golgi-localized probes.

Keywords: Quinoline, selective synthesis, intramolecular change transfer, fluorescence, cell imaging

Quinolines and their derivatives play a crucial role in organic chemistry due to the applications in pharmaceuticals as well as advanced functional materials.1−4 As the important “star molecules” in various research areas, quinolines continued to receive extensive research interests in the past few years, particularly as the core scaffold to construct medicine molecules5−8 and fluorescent probes for sensing.9−13 Given the importance of the quinoline scaffold in the fields of both pharmaceutical and organic chemistry, synthesis of quinoline derivatives has received tremendous attention since Skraup first reported the classical synthetic method of quinoline in 1880.14 Over the past few decades, numerous methods based on various mechanisms, including Conrad–Limpach–Knorr,15 Friedländer,16 Doebner–von Miller,17 Pfitzinger,18 or Combes,19 have been developed for the preparation of substituted quinolones. However, multiple synthetic steps and harsh reaction conditions, such as high temperatures, strong base, acid or metal catalysts, still limit the applications of these strategies. Therefore, direct catalyst-free approaches with good yields remain highly valuable to broaden the application of quinoline derivatives.

As one of the common cellular organelles, Golgi apparatus is the major collecting, processing, and dispatching station of proteins to be modified and delivered for secretion.20 Since involved in such vital intracellular activities, disruption of Golgi apparatus functions could cause many organ lesions such as eye, kidney, and liver diseases.21 Thus, it is of great significance to develop specialized probes to mark Golgi apparatus. Considering most commercial Golgi markers generally are difficult to be synthesized with complicated structures or high cost,22−24 the development of Golgi-localized small molecule probes has still remained challenging. The application of quinoline derivatives as cell organelle probes is rarely explored, even though it has been widely applied to construct medicine molecules and analyte probes. Moreover, quinoline primarily fluoresces in the near UV region, it is desirable to shift its absorption and emission signals to longer wavelengths without significantly extending the molecular size for biosensing and bioimaging. In this context, charge-transfer state could be used as an effective strategy to mediate excited states.25,26 As a strongly electron-withdrawing group, trifluoromethyl group has been used to form charge-transfer states with electron-donating groups.27−29 Meanwhile, biological and medicinal studies have demonstrated that fluorine-containing compounds also exhibit enhanced biological properties.30−32

Considering both feasible synthetic routines and biological applications of quinolines, we propose here to conduct a catalyst-free reaction of m-phenylenediamine with unsymmetric 1,3-diketones containing a trifluoromethyl group to synthesize various substituted 7-aminoquinolines as novel fluorophors in good yields. Introduction of such a trifluoromethyl group avoids the use of concentrated acid to promote the condensation as well as the subsequent treatment with excess amount of base to liberate the quinoline as previously reported.33 And the strongly electron-withdrawing trifluoromethyl group also potentially enhances intramolecular change transfer (ICT) state of the 7-aminoquolines between the strongly electron-donating amine group and the trifluoromethyl group, thus shifting the absorption and emission of the compounds to the longer wavelengths in polar media.

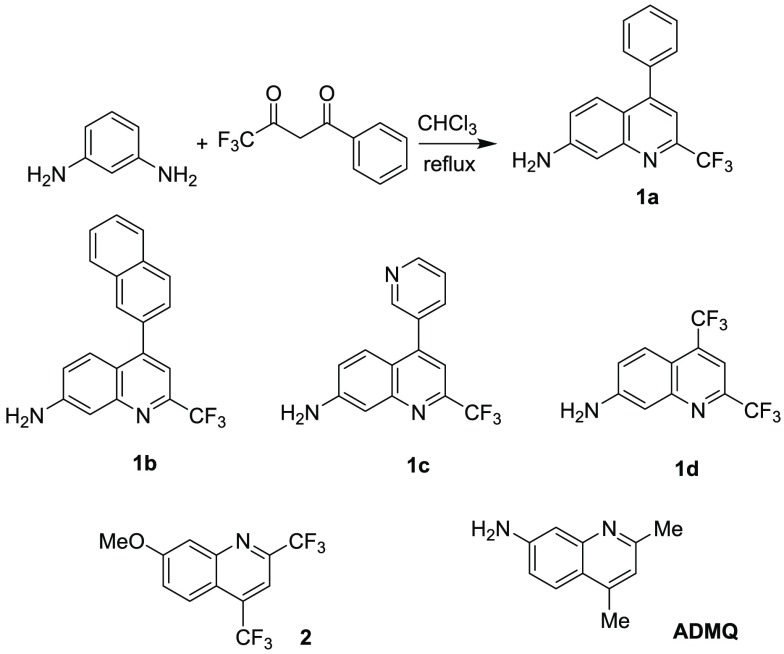

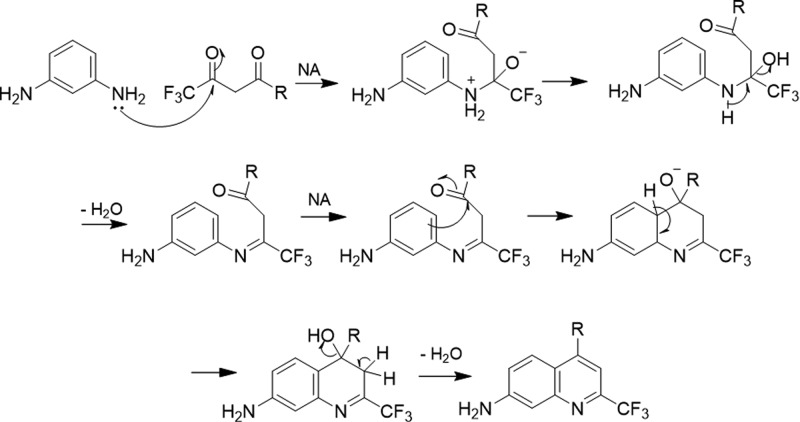

We first tested the reaction of m-phenylenediamine with 4,4,4-trifluoro-1-phenylbutane-1,3-dione. As shown in Scheme 1, after a chloroform solution of the two compounds were heated at reflux for ∼10 h, rotary evaporation of the solvent directly led to light green needle crystals of the product in 88% yield. No strong acid or other catalyst was needed to promote this reaction. Surprisingly, this reaction was found to be able to proceed in a solvent-free solid state! The two starting reactants were thoroughly ground in a mortar, and the resulted pale mixture turned light green overnight at room temperature in the air. 1HNMR spectroscopic analyses confirm the only product structure of 1a, avoiding the formation of regioisomeric products that one would expect for the reaction of m-phenylenediamine with unsymmetric 1,3-diketones. Here, we propose the reaction routine in Scheme 2: the first step is the nucleophilic addition (NA) between one amine group of m-phenylenediamine and the ketone group adjacent to trifluoromethyl group, due to its strong electronegativity. Then a second condensation of the other ketone group with the aromatic ring at 6-position, not 2-position, follows, contributing to the octet rule, to form the final single product 1a. Therefore, using such trifluoromethyl substituted 1,3-diketones has directed a highly selective and efficient condensation to form the 4-CF3-substituted 7-aminoquinoline as a single product.

Scheme 1. Syntheses of 7-Aminoquinolines.

Scheme 2. Proposed Formation Mechanism of 7-Aminoquinolines.

In a similar way, we also conducted the reaction with various substituents on the unsymmetric trifluoromethylated 1,3-diketones to test the versatility of the method to introduce a trifluoromethyl group. Compounds 1b–1d were successfully obtained from the corresponding unsymmetric 1,3-diketones in good yields, demonstrating the strategy could be widely applied. Moreover, when m-phenylenediamine was reacted with hexafluoroacetylacetone, the reaction condition can be so mild that the product 1d could even be produced in water at room temperature (Figure S1), which indicates that the two trifluoromethyl groups further accelerate the reaction.

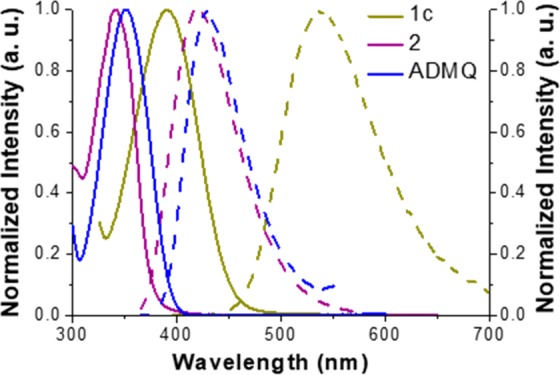

We then studied the fluorescence ICT properties of the 2,4-disubstituted 7-aminoquinolines in various solvents. For comparison, we prepared 7-methoxyquinoline 2 with a methoxy group that is less electron-donating than the amine group and 7-amino-2,4-dimethylquinoline ADMQ with two methyl groups that are less electron-withdrawing than the trifluoromethyl group, and compared their optical properties with the new quinolines. A summary of the optical characterizations of compounds 1a–d, 2, and ADMQ is presented in Table 1. The absorption and emission spectra are also provided (Figures 1 and S2–S7), along with photos showing the solvatochromic fluorescent emissions (Figures S8–S13). In general, the trifluoromethyl-substituted 7-aminoquinolines (1a–1d) show rather strong absorption in the near UV to blue light region. Absorption maxima exhibit gradual bathochromic shifts as the solvent polarity increases, e.g., λmax = 365–368 nm in n-hexane and λmax = 389–399 nm in methanol. The visual emission color changes from violet in n-hexane (λem = 407–435 nm) to greenish yellow (λem = 507–537 nm) in MeOH, indicating increased excited-state dipole moments of these molecules. Presumably this is due to an ICT process from the −NH2 lone pair to the vicinity of the electron-withdrawing −CF3 group. As a result, when −NH2 is replaced with a less powerful electron-donating −OCH3 group, or the strong electron-withdrawing group −CF3 with an electron-donating −CH3 group, the quinoline compounds 2 and ADMQ emit in the violet region in all the solvents (<420 nm), suggesting that the lowest transition consists of more π–π*. Time-correlated fluorescence lifetimes were also measured in different solutions (Table 1). With increasing solvent polarity, fluorescence lifetimes of the 7-aminoquinolines first lengthen (e.g., 1d: 4.96 to 20.0 ns from n-hexane to ethyl acetate) in moderately polar solvents but start to shorten in strongly polar solvents (e.g., 1d: 7.49 ns in methanol). The trend is typical of ICT compounds discussed in a previous publication.34 Briefly speaking, the initially lengthened lifetimes are due to a more forbidden ICT character in moderately polar solvents compared to a pure π–π* transition because the origin and destination orbitals do not entirely overlap in space. Meanwhile, when ICT becomes more dominating in very polar solvents, more dramatic electron redistribution between the donor and acceptor moieties in the excited state can result in subsequent large nuclear reorganization.35 The apparent emission lifetime can thus be compromised with increased thermal quenching.

Table 1. Optical Properties of Quinoline Compounds 1a–1d, 2, and ADMQ in Different Solutions.

| solventa | A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| εb | 1.88 | 2.38 | 4.81 | 6.02 | 7.58 | 8.93 | 20.56 | 32.66 |

| 1a λmax (nm)c | 368 | 375 | 371 | 384 | 389 | 373 | 387 | 389 |

| λem (nm)d | 407 | 442 | 468 | 472 | 473 | 449 | 483 | 507 |

| τF (ns)e | 2.89 | 4.56 | 5.82 | 7.22 | 8.04 | 3.63 | 8.93 | 7.84 |

| 1b λmax (nm) | 367 | 375 | 372 | 387 | 391 | 374 | 389 | 392 |

| λem (nm) | 409 | 452 | 469 | 477 | 480 | 446 | 487 | 513 |

| τF (ns) | 3.89 | 5.17 | 4.55 | 6.13 | 6.66 | 4.30 | 7.01 | 6.72 |

| 1c λmax (nm) | 365 | 374 | 372 | 382 | 387 | 373 | 386 | 391 |

| λem (nm) | 435 | 475 | 500 | 503 | 512 | 475 | 517 | 537 |

| τF (ns) | 4.24 | 12.9 | 13.7 | 15.6 | 15.9 | 12.2 | 14.7 | 5.50 |

| 1d λmax (nm) | 368 | 383 | 379 | 393 | 397 | 380 | 396 | 399 |

| λem (nm) | 413 | 461 | 484 | 489 | 495 | 464 | 501 | 527 |

| τF (ns) | 4.96 | 15.7 | 17.5 | 19.5 | 20.0 | 16.7 | 19.7 | 7.49 |

| 2 λmax (nm) | 336 | 341 | 341 | 341 | 342 | 341 | 342 | 341 |

| λem (nm) | 376 | 398 | 392 | 402 | 402 | 396 | 406 | 417 |

| τF (ns) | 0.68 | 3.97 | 2.25 | 4.18 | 4.16 | 2.57 | 5.19 | 7.58 |

| ADMQ λmax | 339 | 344 | 350 | 347 | 344 | 343 | 349 | 351 |

| λem (nm) | 374 | 393 | 407 | 401 | 398 | 390 | 408 | 429 |

| τF (ns) | 0.02 | 3.73 | 6.08 | 4.55 | 2.10 | 2.88 | 5.28 | 0.17 |

A, n-hexane; B, toluene; C, chloroform; D, ethyl acetate; E, tetrahydrofuran; F, dichloromethane; G, acetone; H, MeOH.

Dielectric constant of the solvent.

λmax = absorption maximum in solution.

λem = emission maximum in solution (excited at 365 nm).

τF = pre-exponent-weighted fluorescence lifetime.

Figure 1.

Normalized absorption (solid line) and emission spectra (dashed line) of 1c, 2, and ADMQ in methanol solutions.

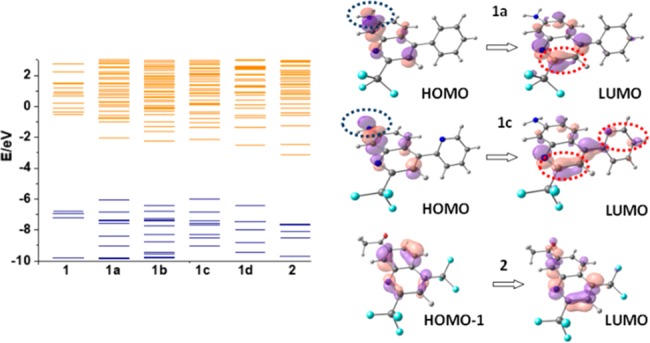

In order to gain further understanding on the optical properties of these compounds, quantum chemistry calculations were performed with the Gaussian09 package. The optimized geometry and electronic structures were simulated with density function theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6-31G level (Figure 2). The frontier orbitals of compounds 1a–1d possess close energy levels, while the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of 2 is much lower in energy. The higher HOMOs for 1a–1d are evidently caused by the presence of the amino group since the starting material m-phenylenediamine (1) has a comparable HOMO energy level. As shown in Figure 2, for 7-aminoquinolines 1a–1d, the HOMOs and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbitals (LUMOs) are more concentrated on the amino group and near the −CF3 group, respectively, indicating a strong ICT character. For 2, however, the overlap of the HOMO and the LUMO is significantly better and is thus more likely to exhibit a vertical π–π* state as the lowest transition. Therefore, both the trifluoromethyl group and amino group are essential to form valid ICT states among the new quinolones.

Figure 2.

Calculated main origin and destination orbitals involved in the lowest singlet transition states of compounds 1 (m-phenylenediamine), 1a, 1c, and 2. Blue and red circles represent regions with the highest electron density in the ground and in the excited states, respectively.

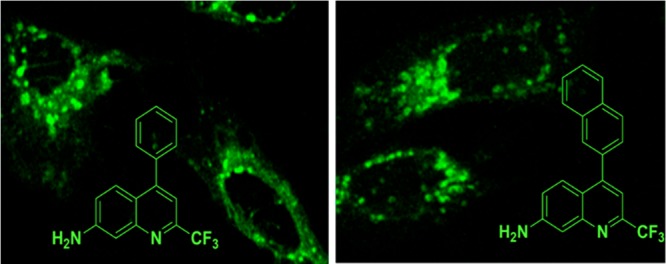

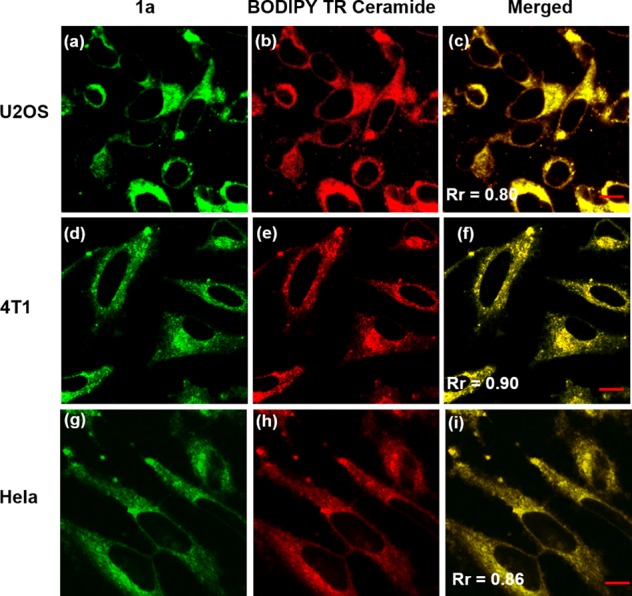

On account of the extensive applications of quinolines in bioimaging and the substantial ICT character of these 7-aminoquinolines, we then explored their feasibilities as fluorescent cell imaging agents. All the ICTQs (intramolecular charge transfer quinolines 1a–1d, 2 μg/mL) in buffer solutions were added to U2OS cells growing at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. We found that 1a and 1b exhibited the best brightness and photostability. After 30 min, the live cells were taken under a fluorescence microscope for one-photon imaging. Surprisingly, the compounds tended to specifically locate in the peri-nuclear region of the cells, which might be the Golgi apparatus after being internalized (Figures 3a and S14a). In order to exclude the specialty of one kind of cells, we also conducted the experiments with two other cell lines (HeLa and 4T1 cells) under the same conditions. As shown in Figure 3d, g, 1a and 1b (Figure S14d,g) present similar locations in the Golgi apparatus with strong green emission, which demonstrates that our quinolone dyes possess versatile cell imaging properties. IC50 tests were also conducted to evaluate the toxicity of 1a and 1b (Figure S15). The calculated IC50 values for 1a and 1b are 3.37 and 3.44, respectively; thus, the half maximal inhibitory concentrations are 2.34 and 2.72 μg/mL, respectively. Since the experimental concentration of 1a and 1b is 2 μg/mL in the present work, no obvious cytotoxicity for these two dyes was noted during all of the cell culture experiments.

Figure 3.

Confocal fluorescence micrographs showing stained Golgi apparatuses by 1a (a, d, g: λex = 488 nm; emission range 489–580 nm) and BODIPY TR Ceramide (b, e, h: λex = 633 nm; emission range 634–740 nm), and the merged images (c, f, i). Scale bar: 10 μm.

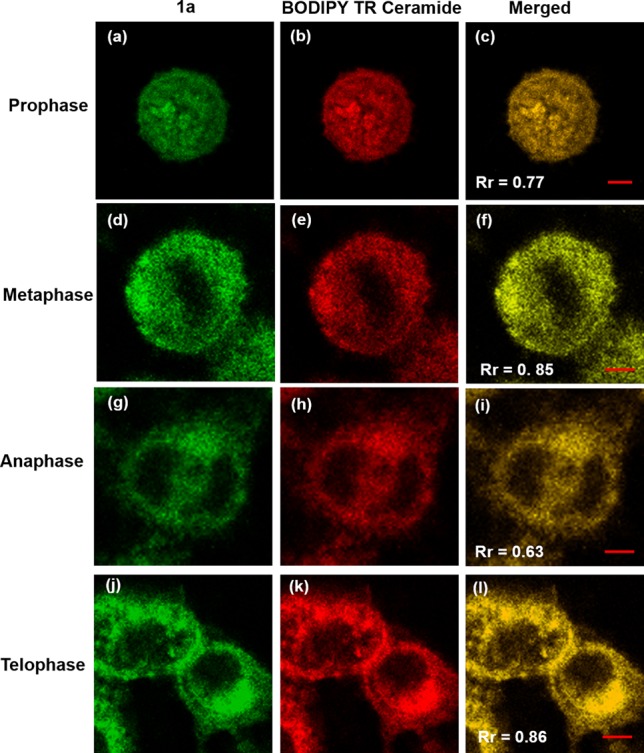

To investigate the cellular location specificity of 1a and 1b, the cells were cross-stained with BODIPY TR Ceramide, a commercial red-emissive marker for the Golgi apparatus, and examined under a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope. All the images for the three cell lines exhibit a complete distribution overlap with the Pearson’s correlation coefficients, Rr larger than 0.50 (Figure 3c, f, i and Figure S14c, f, i). Those high Rr values demonstrate that 1a and 1b exhibit excellent specificity for Golgi apparatus.36 An antigiantin antibody of Golgi apparatus was also cross-stained with 1a and 1b to test their specificity for Golgi apparatus in HeLa cells (Figure S16). The Rr values are 0.65 and 0.83 for 1a and 1b, respectively, confirming their highly target-specific Golgi apparatus properties. Further, we also examined the colocalization of our dye 1a and BODIPY TR Ceramide during the mitosis in living HeLa cells. The imaging results of different subphases are presented in Figure 4. The Rr values for prophase, prophase, anaphase, and telophase were found to be 0.77, 0.85, 0.63, and 0.86, respectively, showing that 1a and BODIPY TR Ceramide still show good distribution overlap in different subphases of mitosis. We preliminarily ascribe the highly target-specific Golgi imaging in vitro of 1a and 1b to the basicity of pyridyl moiety, considering that the Golgi apparatus is slightly acidic (6.0–6.7).37 Together, these colocalization results confirm that 1a and 1b have the same intracellular localization as BODIPY TR Ceramide and can be potentially used as low cost Golgi probes to replace the more costly commercial ones.

Figure 4.

Subcellular localizations in synchronously dividing HeLa cells of 1a (a, d, g, j: λex = 488 nm; emission range 489–580 nm) and BODIPY TR Ceramide (b, e, h, k: λex = 633 nm; emission range 634–740 nm), and the merged images (c, f, i, l). Scale bar: 5 μm.

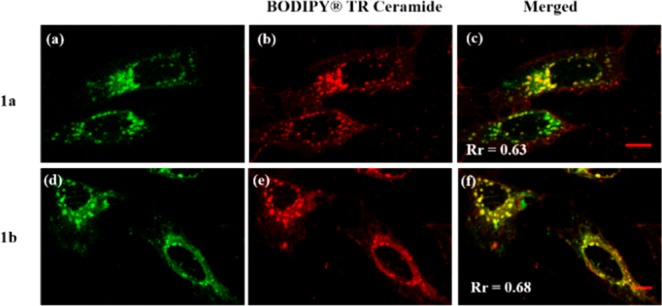

Compared to one photon UV-excitation, two-photon microscopy (TPM), which utilizes a longer wavelength excitation source, owns the advantages of negligible background signal, deeper tissue penetration depth, reduced phototoxicity, and photobleaching.38 It is well-known that a strong ICT state is typically associated with two-photon absorption (TPA) characteristics, which can be beneficial for bioimaging applications.39,40 Given their remarkable ICT character, we also tested 1a and 1b for two-photon imaging capability in U2OS cells. The absorption maxima of the fluorophores are ∼400 nm in protic solvents, indicating that the optimal TPA wavelength is in the 780–800 nm range. To our delight, despite their small sizes, both of these two dyes exhibited very strong two-photon induced emission under the 790 nm laser excitation (Figure 5). The merged images also show perfect colocalizations in the Golgi apparatus with BODIPY TR Ceramide. The Rr values are 0.63 and 0.68 for 1a and 1b, respectively. These initial results have demonstrated the imminent application potential of these ICTQs as both one- and two-photon fluorescence cell imaging.

Figure 5.

Two-photon fluorescence micrographs showing stained Golgi apparatuses within U2OS cells by 1a (a) and 1b (d) (λex = 790 nm; emission range 371–580 nm); one-photon fluorescence micrographs showing stained Golgi apparatuses by BODIPY TR Ceramide (b, e, λex = 633 nm; emission range 634–740 nm); merged images showing almost perfect overlaps between the quinoline and BODIPY TR Ceramide dyes (c, f). Scale bar: 10 μm.

In summary, we have conducted a highly selective and efficient condensation of m-phenylenebenzene with unsymmetric 1,3-diaketones to generate 2,4-disubstituted 7-aminoquinolines, by incorporating a strongly electron-withdrawing trifluoromethyl group. The introduction of such a trifluoromethyl group avoids the use of strong acid or other catalyst and also enhances the ICT process within 7-aminoquinolines from the strongly electron-donating amine group and the strongly electron-withdrawing trifluoromethyl group. These novel 7-aminoquinolines show large bathochromic shift going from nonpolar solvents to highly polar solvents. Interestingly, two of the new 7-aminoquinolines appear to exhibit high specificity for the Golgi apparatus as demonstrated by colocalization experiments with a commercial Golgi apparatus marker, BODIPY TR Ceramide, in various cell lines (HeLa, U2OS, and 4T1 cells). Furthermore, the dyes have exhibited potentials in both one- and two-photon fluorescence cell imaging. These preliminary findings provide new insights into developing low cost probes and drug delivery engineering with small quinoline molecules for Golgi apparatus. Currently, we are exploring the synthesis of red-emitting ICT quinolines for more useful life science applications.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Rui Fu (RNA Bioscience Initiative, University of Colorado School of Medicine) for the helpful discussion about cell imaging.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- ICT

intramolecular charge transfer

- ADMQ

7-amino-2,4-dimethylquinoline

- ICTQs

intramolecular charge transfer quinolines

- TPA

two-photon absorption

- HOMO

highest occupied molecular orbital

- LUMO

lowest unoccupied molecular orbital.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00118.

Detailed experimental procedures and spectral data for all new compounds (PDF)

Author Contributions

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21876113 to G. Li, 21803038 to X. Chen).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Adsule S.; Barve V.; Chen D.; Ahmed F.; Dou Q. P.; Padhye S.; Sarkar F. H. Novel schiff base copper complexes of quinoline-2 carboxaldehyde as proteasome inhibitors in human prostate cancer cells. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 7242–7246. 10.1021/jm060712l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay K. D.; Dodia N. M.; Khunt R. C.; Chaniara R. S.; Shah A. K. Synthesis and biological screening of pyrano[3,2-c]quinolone analogues as anti-inflammatory and anticancer agents. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 283–288. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laras Y.; Hugues V.; Chandrasekaran Y.; Blanchard-Desce M.; Acher F. C.; Pietrancosta N. Synthesis of quinoline dicarboxylic esters as biocompatible fluorescent tags. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 8294–8302. 10.1021/jo301652j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu D.; Chen L.; Ma S.; Luo H.; Cao J.; Chen R.; Duan Z.; Mathey F. Synthesis of 1,3-azaphospholes with pyrrolo[1,2-a]quinoline skeleton and their optical applications. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 4103–4106. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b01663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley M.; Tilley L. Quinoline antimalarials: mechanisms of action and resistance and prospects for new agents. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998, 79, 55–87. 10.1016/S0163-7258(98)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene J. A.; Jones D. S.; Podolsky S. H. Therapeutic evolution and the challenge of rational medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1077–1082. 10.1056/NEJMp1113570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur K.; Jain M.; Reddy R. P.; Jain R. Quinolines and structurally related heterocycles as antimalarials. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 3245. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. K.; Singh S. A brief history of quinoline as antimalarial Agents. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2014, 25, 295. [Google Scholar]

- Li G.; Zhu D.; Xue L.; Jiang H. Quinoline-based fluorescent probe for ratiometric detection of lysosomal pH. Org. Lett. 2013, 15, 5020–5023. 10.1021/ol4023547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed B. N.; Ghosh P. A chelation enhanced selective fluorescence sensing of Hg2+ by a simple quinoline substituted tripodal amide receptor. Dalton Trans 2011, 40, 12540–12547. 10.1039/c1dt10923e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutariya P. G.; Pandya A.; Lodha A.; Menon S. K. Fluorescence switch on–off–on receptor constructed of quinoline allied calix[4]arene for selective recognition of Cu2+ from blood serum and F– from industrial waste water. Analyst 2013, 138, 2531–2535. 10.1039/c3an00209h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikata Y.; Ugai A.; Ohnishi R.; Konno H. Quantitative fluorescent detection of pyrophosphate with quinoline-ligated dinuclear zinc complexes. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 10223–10225. 10.1021/ic401605m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W.; Yan J.; Springsteen G.; Deeter S.; Wang B. A novel type of fluorescent boronic acid that shows large fluorescence intensity changes upon binding with a carbohydrate in aqueous solution at physiological pH. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003, 13, 1019–1022. 10.1016/S0960-894X(03)00086-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skraup V. Z. H.; Vorläufige M. Eine Synthese des Chinolins. Bull. soc. Chira. 1880, 28, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Misani F.; Bogert M. T. The search for superior drugs for tropical diseases. II. Synthetic studies in the quinoline and phenan-throline series. Skraup and Conrad-Limpach-Knorr reactions. J. Org. Chem. 1945, 10, 347–365. 10.1021/jo01180a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladiali S.; Chelucci G.; Mudadu M. S.; Gastaut M. A.; Thummel R. P. Friedländer synthesis of chiral alkyl-substituted 1, 10-phenanthrolines. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 400–405. 10.1021/jo0009806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisch J. J.; Dluzniewski T. Mechanism of the Skraup and Doebner-von Miller quinoline syntheses: cyclization of, /3-unsaturated N-aryliminium salts via 1,3-diazetidinium ion intermediates. J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 1269. 10.1021/jo00267a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buu-Hoi N. P.; Royer R.; Xuong N. D.; Jacquignon P. The Pfitzinger reaction in the synthesis of quinoline derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 1953, 18, 1209–1224. 10.1021/jo50015a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Combes A. Quinoline synthesis. Bull. Chim. Soc. France 1888, 49, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Lodish H.; Bark A.; Zipersky S. L.; Matsudaira P.; Baltimore D.; Darnell J.. Molecular Cell Biology, 4th ed; W. H. Freeman: New York, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Aridor M.; Hannan L. A. Traffic jam: a compendium of human diseases that affect intracellular transport processes. Traffic 2000, 1, 836. 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.011104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. X.; Li H.; Chan C. F.; Lan R.; Chan W. L.; Law G. L.; Wong W. K.; Wong K. L. A potential water-soluble ytterbium-based porphyrin–cyclen dual bio-probe for Golgi apparatus imaging and photodynamic therapy. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9646–9648. 10.1039/c2cc34963a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Fan J.; Wang J.; Zhang S.; Dou B.; Peng X. An off–on COX-2-specific fluorescent probe: targeting the golgi apparatus of cancer cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11663–11669. 10.1021/ja4056905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh H.; Lee H. W.; Heo C. H.; Byun J. W.; Sarkar A. R.; Kim H. M. A Golgi-localized two-photon probe for imaging zinc ions. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 12099–12102. 10.1039/C5CC03884G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberhauer G.; Gleiter R.; Burkhart C. Planarized intramolecular charge transfer: a concept for fluorophores with both large stokes shifts and high fluorescence quantum yields. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 971–978. 10.1002/chem.201503927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y.; Yokoyama K. Design and synthesis of intramolecular charge transfer-based fluorescent reagents for the highly-sensitive detection of proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 17799–17802. 10.1021/ja054739q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maliakal A.; Lem G.; Turro N. J.; Ravichandran R.; Suhadolnik J. C.; DeBellis A. D.; Wood M. G.; Lau J. Twisted intramolecular charge transfer states in 2-arylbenzotriazoles: fluorescence deactivation via intramolecular electron transfer rather than proton transfer. J. Phys. Chem. A 2002, 106, 7680–7689. 10.1021/jp021000j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shavaleev N. M.; Scopelliti R.; Graetzel M.; Nazeeruddin M. K.; Pertegas A.; Roldan-Carmona C.; Tordera D.; Bolink H. J. Pulsed-current versus constant-voltage light-emitting electrochemical cells with trifluoromethyl-substituted cationic iridium (iii) complexes. J. Mater. Chem. C 2013, 1, 2241–2248. 10.1039/c3tc00808h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galievsky V. A.; Zachariasse K. A. Intramolecular charge transfer with N,N-Dialkyl-4-(trifluoromethyl)anilines and 4-(dimethylamino)benzonitrile in polar solvents. Investigation of the excitation wavelength dependence of the reaction pathway. Acta Phys. Polym., A 2007, 112, S39–S56. 10.12693/APhysPolA.112.S-39. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filler R.; Kobayashi Y.; Yagupolskii L. M.. Organofluorine Compounds in Medicinal Chemistry and Biomedical Applications; Elsevier, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bégué J. P.; Bonnet-Delpon D.. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry of Fluorine; John Wiley & Sons, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ojima I.Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology; John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Su Q.; He M.; Wu Q.; Gao W.; Xu H.; Ye L.; Mu Y. The supramolecular assemblies of 7-amino-2, 4-dimethylquinolinium salts and the effect of a variety of anions on their luminescent properties. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 7275–7286. 10.1039/c2ce25883h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S.; Evans R. E.; Liu T.; Zhang G.; Demas J.; Trindle C. O.; Fraser C. L. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 3597–3610. 10.1021/ic300077g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski Z. R.; Rotkiewicz K.; Rettig W. Aromatic difluoroboron β-diketonate complexes: effects of π-conjugation and media on optical properties. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103, 3899–4032. 10.1021/cr940745l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinchuk V.; Grossenbacher-Zinchuk O. Recent advances in quantitative colocalization analysis: focus on neuroscience. Prog. Histochem. Cytochem. 2009, 44, 125–172. 10.1016/j.proghi.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey J. R.; Grinstein S.; Orlowski J. Sensors and regulators of intracellular pH. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 50–61. 10.1038/nrm2820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmchen F.; Denk W. Deep tissue two-photon microscopy. Nat. Methods 2005, 2, 932–940. 10.1038/nmeth818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo H. Y.; Liu B.; Kohler B.; Korystov D.; Mikhailovsky A.; Bazan G. C. Solvent effects on the two-photon absorption of distyrylbenzene chromophores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 14721–14729. 10.1021/ja052906g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G.; Pu K. Y.; Zhang X.; Li K.; Wang L.; Cai L.; Ding D.; Lai Y. H.; Liu B. Star-shaped glycosylated conjugated oligomer for two-photon fluorescence imaging of live cells. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23, 4428–4434. 10.1021/cm201377u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.