Abstract

Background

Cysticercosis is spreading all over the world and it is a major health problem in most countries of Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Extensive disseminated cysticercosis is relatively rare and fewer than 120 case have been reported in the worldwide. We reported a rare case of extensive disseminated cysticercosis in Yunan province, China.

Case presentation

A rare case of extensive disseminated cysticercosis, in a 61-year-old male Chinese was detected from Yunnan province in 2018. Clinical and etiological examination was performed, as well as the epidemiological investigation.

Conclusion

The life cycle of T. solium in the area where the case came from is complete. We expect this case could raise the attentions to the control of Taenia solium infection and subsequent cysticercosis there.

Keywords: Extensive disseminated cysticercosis, Taenia solium, Control

Background

Cysticercosis refers to a parasitic infection caused by the larvae of the pork tapeworm Taenia solium [1, 2]. In 2010 and 2014, it was listed as one of the neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) and negligible zoonotic diseases (NZDs) by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), respectively [3]. Cysticercosis is spreading all over the world and it is a major health problem in most countries of Latin America, Africa, and Asia [1]. With the globalization and increasing exchanges between countries, more and more cases of cysticercosis have been reported in non-endemic areas, and cysticercosis was classified as an emerging infectious disease in some developed countries [1, 4]. In China, this disease is mainly endemic in southwestern areas, especially in Yunnan province where a fair portion of the residents have the habit of consuming raw or undercooked pork [4]. Cysticercosis can involve any tissue of the body, such as central nervous system, subcutaneous tissue, eyes and muscles [1, 2]. The central nervous system is most commonly afflicted in clinical cases [5, 6]. However, extensive disseminated cysticercosis is relatively rare and fewer than 120 case have been reported in the worldwide, the majority of which were in India [7–12]. Here, we reported a rare case of extensive disseminated cysticercosis from Yunan province, China. It is expected the control of Taenia solium infection and subsequent cysticercosis could be paid attentions there.

Case presentation

In March 2018, a case with extensive disseminated cysticercosis was admitted in the medical department affiliated to the Institute of Research and Control on Schistosomiasis in Dali city. A 61-year-old male reported that his left lower extremity was treated because of fall fracture in a local hospital three years ago. During the examination, the doctor found multiple cysticercroid nodules in the intramuscular. Then, after the fracture was cured, the patient went to other hospitals and received three rounds of treatments for cysticercosis. However, we were unable to obtain the details of that treatment history of the patient. Recently, the patient felt mild headaches and dizziness. Then, he came to this hospital. A comprehensive investigation was carried out for the patient including symptom, physical examinations, imaging examinations, etiological examinations and epidemiological investigations.

Symptom and physical examinations: symptom and physical examinations were performed immediately after the patient was hospitalized. In addition to mild headaches and dizziness, the patient reported no other symptoms. No abnormality was found in physical examinations: 36.5°C of body temperature, 90 per min of pulse rate, 19 per min of breath rate, and 97/68 mmHg of blood pressure.

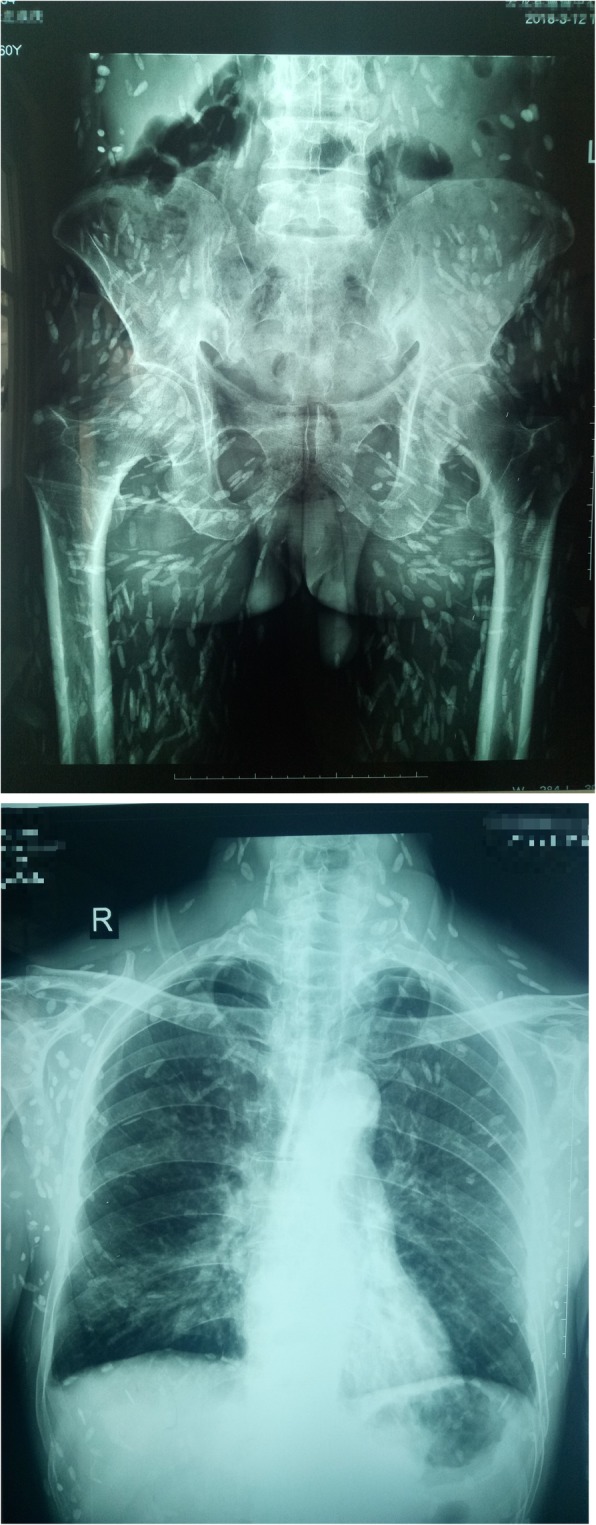

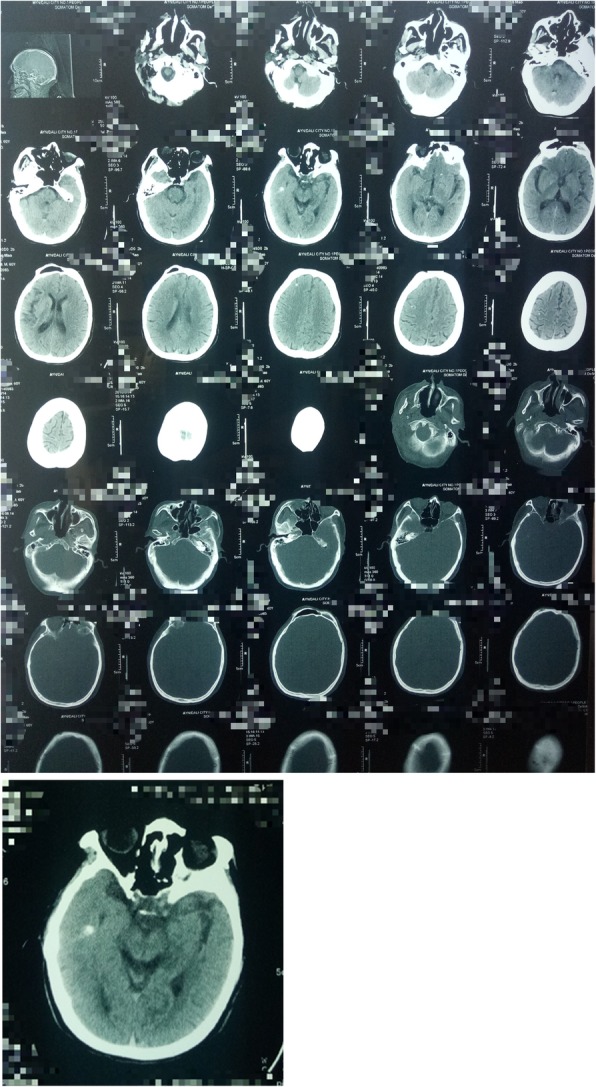

Imaging examination: X-ray examination was done on March 12, 2018. Hundreds of calcification spots due to cysticercosis following the muscle planes were found (Fig. 1). Calcified foci were disseminated around the whole body, showing a “meteoroid”. The calcification of cysticerci presented as long spindles, long ovals, or elongated strips. Size of the calcareous cysticerci varied with clear outlines and some overlapped. The major axis of the calcification was mostly consistent with the direction of muscle fibers. Through the x-ray film, the patient had high systemic calcification density, with uneven distribution, namely high in limbs and less in trunk. On March 14, 2018, computed tomography (CT) scan was performed for the brain (Fig. 2). Bilateral nodules with multiple nodular calcifications were shown in bilateral cerebral hemispheres, with a diameter of approximately 1–2 mm, which met the diagnostic criteria for definite neurocysticercosis [13–15]. There existed no obvious abnormality in the binocular ultrasound. Finally, this case was diagnosed as mixed infection of neurocysticercosis and muscle cysticercosis.

Fig. 1.

X-ray slices (Calcified foci were disseminated around the whole body, showing a “meteoroid”. The calcification of cysticerci presented as long spindles, long ovals, or elongated strips. Size of the calcareous cysticerci varied with clear outlines and some overlapped)

Fig. 2.

Brain CT scan (Bilateral nodules with multiple nodular calcifications were shown in bilateral cerebral hemispheres, with a diameter of approximately 1–2 mm)

Etiological examination: the patient’s blood and feces were examined. Antibody test against cysticercosis was performed with the kit (IgG) purchased from Shenzhen Kangbide Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Positive finding was presented. Fecal examination was done, but no eggs or proglottids of T. solium were found in the feces.

Epidemiological investigation: The patient grew up and mostly lived in Yunlong county, Dali city, where taeniasis and cysticercosis are endemic [4]. Pigs were raised by his family, and mostly self-slaughtered without any inspection and quarantine. Occasionally, pork was also sold in the community and surrounding markets. The patient reported that he had consumed pork containing cysticerci, but denied that he had a history of expelling worms or proglottids. His family members also denied cysticercosis-related symptoms and the history of expelling worms or proglottids. The sanitation was poor in patient’s community and raising pigs were common there. The patient told us a few people in the community had cysticercosis and taeniasis. Traditional toilets were available in the villages, but faeces were usually used as a farmyard fertilizer without harmless treatment. The drinking water in the community was mostly spring water or snowmelt. The patient and his neighbors liked to eating raw vegetables, and drinking unboiled water, and sometimes ingested undercooked pork. Based on the epidemiological information obtained, it is suspected that the life cycle of T. solium was complete in the community where the case lived. Then, we investigated the records of cysticercosis patients treated in the hospital from 2014 to 2018. It was found that there were another 13 cases of cysticercosis in the town where the patient was located. Thus, it is believed that the life cycle of T. solium was complete in the community where the case lived.

Treatment and follow-up: Patients accepted cysticidal treatment based on the hospital’s guideline. Firstly, albendazole was administrated at 20 mg/kg daily for 10 days and then followed by praziquantel at 20 mg/kg daily for 6 days. Two months later, the patient followed the doctor’s advice for a second course of treatment as above. Because the patient did not feel any abnormal, the patient refused to a further imaging check due to economic factor.

Discussion

Cysticercosis is a prevalent zoonosis in China. A human case of cysticercosis was first reported in China by Barnes in 1922 [16]. China has conducted two national surveys on parasitic diseases. About 1.3 million persons were estimated with Taenia spp. infection in 1988–1992, and then 0.55 million was estimated in 2001–2004 [4]. Although the prevalence of taeniasis in China is decreasing, taeniasis and cysticercosis are still endemic in the southwestern part of China. Such factors cause the endemicity of taeniasis and cysticercosis there as ingestion of undercooked pork and raw vegetables, drinking of unboiled water, using of traditional toilets, free-roaming of pigs, etc. [5, 17–19]. Based on our epidemiological survey, it is believed the life cycle of T. solium was complete in the community where the case came from. Therefore, if no effective measures are implemented, the endemicity will continue there.

Cysticercosis is caused by the infection with the larval stage of T. solium. The case reported here had thousands of calcifications, which may be caused by the ingestion of many eggs of T. solium once or accumulative effects of repeated ingestions. By checking the hospital records, we found another 13 patients with cysticercosis in the town where this patient lived, between 2014 and 2018, but all of those 13 cases belong to NCC, only the patient in this study was extensive disseminated cysticercosis. Disseminated cysticercosis is more common in India. Some studies have suggested that genetic abnormalities may be responsible for a high incidence of disseminated cysticercosis in the Indian population, and they noted that Toll-like receptor 4 gene abnormalities confer genetic susceptibility to disseminated cysticercosis as well [12]. However, due to the limitations of the conditions, we did not detect genetic polymorphism in this patient.

Clinical manifestations of cysticercosis depend upon the location of the cyst, cyst burden and host reaction [10]. Cysts in muscles may manifest as muscular pain, weakness, or pseudohypertrophy; cysts in subcutaneous is frequently asymptomatic but may manifest palpable nodules; and cysts in central nervous system usually cause epilepsy [1, 2, 13, 15]. However, this case did not have the typical symptoms of cysticercosis, only with mild headaches and dizziness, which may be due to the difference in host reactions.

Early detection and diagnosis are important for cysticercosis and taeniasis [20–22]. Early diagnosis and treatment can improve the prognosis of cysticercosis [21, 22]. Early detection and treatment of patients with taeniasis can not only reduce the burden of the patients themselves, but also reduce the risk of the patients as a source of infection to others [20]. Therefore, the application and promotion of advanced diagnostic technology and equipment in endemic area has become particularly important. However, cysticercosis and taeniasis are more prevalent in economically underdeveloped areas, so advanced diagnostic equipment and methods are usually unavailable in some endemic areas [1].

T. solium infection is one of the few diseases, which are considered to will be eliminated and eventual eradicated by the International Task Force for Disease Eradication [23]. The following factors make the eradication possible: human beings are the only definitive host; human feces can be effectively controlled; through animal inspection and quarantine, pork containing cysticercosis can be eliminated from the market; infected pigs and humans can be diagnosed through the diagnostic tests for taeniasis and cysticercosis; currently there are effective treatment regimens for taeniasis and cysticercosis [15, 21–23]. Epidemiologic studies have shown that people who live close with cysticercosis have a three times higher risk of serologically positive for cysticercosis than the control group [21]. Thus, it is recommended to screen the case’s family members and the residents in the community, e.g. fecal examinations and serological examinations. If eggs or parasites are detected in the feces, further deworming treatment should be carried out. If the cysticercus antibody is positive, further imaging examination is required to confirm the diagnosis and treatment. Scavenging of food and coprophagy were associated with T. solium cysticercosis risk [24] and thus pork should be inspected, and hygiene sanitation should be established including the proper disposal of human feces. Additionally, health education is recognized as an important tool in the control of cysticercosis [25–27], and some studies have shown that health education can effectively reduce human cysticercosis and taeniasis [28, 29]. Thus, health education should be implemented to increase the awareness and then change the raw-eating habits associated with taeniasis and cysticercosis. Regular physical examinations of residents in endemic areas will be beneficial to the early detection of cysticercosis, changes in life style can reduce the risk of taeniasis and cysticercosis, and the attentions and subsequent interventions from health and other departments will facilitate the control and elimination of taeniasis and cysticercosis.

Conclusion

The life cycle of T. solium in the area where the case came from is complete. We expect this case could raise the attentions to the control of T. solium infection and subsequent cysticercosis there.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CT

Computed tomography

Authors’ contributions

SZL and MBQ designed the study and revised the manuscript. XZZ wrote the draft of the manuscript. HKL and YHL examined and treatment patients. HZL, CHZ and YDC critically revised the article for the important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Funding: This study was supported by the National Special Science and Technology Project for Major Infectious Diseases of China (Grant No. 2012ZX10004–220, 2016ZX10004222–004). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the paper.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are include within the article. Mr. Xin-Zhong Zang is the contact person for Availability of data and materials.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the by the Ethics Committees of the National Institute of parasitic disease (NIPD), Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (No.: 20180814). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient. No animal work was carried out as part of this study.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Xin-Zhong Zang, Email: Zangxinzhong2011@126.com.

Huan-Zhang Li, Email: willzh@yeah.net.

Men-Bao Qian, Email: qianmb@nipd.chinacdc.cn.

Ying-Dan Chen, Email: chenyd@nipd.chinacdc.cn.

Chang-Hai Zhou, Email: zhouch@nipd.chinacdc.cn.

Hong-Kun Liu, Email: dalilhk@126.com.

Yu-Hua Liu, Email: daliliuyuhua@126.com.

Shi-Zhu Li, Email: stoneli1130@126.com.

References

- 1.García HH, Gonzalez AE, Evans CAW, Gilman RH. Taenia solium cysticercosis. Lancet. 2003;362(9383):547–556. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14117-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Del BOH, Garcia HH. Taenia solium Cysticercosis--The lessons of history. J Neurol Sci. 2015;359(1–2):392–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Taeniasis. Available from: https://www.who.int/taeniasis/en/. Accessed 30 Apr 2019.

- 4.Office of National Survey of Current Status of Major Human Parasitic Diseases Report on the National Survey of current status of major human parasitic diseases in China [in Chinese] Chin J Parasitol Parasit Dis. 2005;23(b10):332–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang W, Chen F, Wang YY. Epidemiological analysis of hospitalized cases of cysticercosis in Dali prefecture from 1999 to 2006 [in Chinese] J Pathogen Biol. 2009;4:298–300. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kanhere S, Bhagat M, Phadke V, George R. Isolated intramuscular Cysticercosis: a case report. Malays J Med Sci. 2015;22(2):65–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhalla A, Sood A, Sachdev A, Varma V. Disseminated cysticercosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Kumar A, Bhagwani DK, Sharma RK, Kavita SS, Datar S, Das JR. Disseminated cysticercosis. Indian Pediatr. 1996;33(4):337–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park SY, Kong MH, Kim JH, Song KY. Disseminated Cysticercosis. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;49(3):190–193. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2011.49.3.190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khandpur S, Kothiwala S, Basnet B, Nangia R, Venkatesh HA, Sharma R. Extensive disseminated cysticercosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2014;80(2):137. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.129389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin M-P, Chen Y-L, Tzeng W-S. Extensive disseminated cysticercosis. BMJ Case Reports. 2014;2014:bcr2013202807. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-202807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qavi A, Garg RK, Malhotra HS, Jain A, Kumar N, Malhotra KP, Srivastava PK, Verma R, Sharma PK. Disseminated cysticercosis. Medicine. 2016;95(39):e4882. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Brutto OH. Neurocysticercosis: A Review. Scientific World J. 2012;2012:1–8. doi: 10.1100/2012/159821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bazan R, Hamamoto Filho PT, Luvizutto GJ, Nunes HRC, Odashima NS, dos Santos AC, Elias Júnior J, Zanini MA, Fleury A, Takayanagui OM. Clinical symptoms, imaging features and cyst distribution in the cerebrospinal fluid compartments in patients with Extraparenchymal Neurocysticercosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016;10(11):e0005115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carpio A, Fleury A, Romo ML, Abraham R, Fandiño J, Durán JC, Cárdenas G, Moncayo J, Leite Rodrigues C, San-Juan D, et al. New diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis: reliability and validity. Ann Neurol. 2016;80(3):434–442. doi: 10.1002/ana.24732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen Y, Xu L, Zhou X. Distribution and disease burden of cysticercosis in China. Southeast Asian J Tropical Med Public Health. 2004;35:231–239. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nkouawa A, Dschanou AR, Moyou-Somo R, Sako Y, Ito A. Seroprevalence and risk factors of human cysticercosis and taeniasis prevalence in a highly endemic area of epilepsy in Bangoua, West Cameroon. Acta Trop. 2017;165:116–120. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Openshaw John J., Medina Alexis, Felt Stephen A., Li Tiaoying, Huan Zhou, Rozelle Scott, Luby Stephen P. Prevalence and risk factors for Taenia solium cysticercosis in school-aged children: A school based study in western Sichuan, People’s Republic of China. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2018;12(5):e0006465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao W, van der Ploeg CP, Xu J, Gao C, Ge L, Habbema JD. Risk factors for human cysticercosis morbidity: a population-based case-control study. Epidemiol Infect. 1997;119(2):231–235. doi: 10.1017/S0950268897007619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bustos JA, Rodriguez S, Jimenez JA, Moyano LM, Castillo Y, Ayvar V, Allan JC, Craig PS, Gonzalez AE, Gilman RH, et al. Detection of Taenia solium Taeniasis Coproantigen is an early Indicator of treatment failure for Taeniasis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2012;19(4):570–573. doi: 10.1128/CVI.05428-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rizvi SAA, Saleh AM, Frimpong H, Al Mohiy HM, Ahmed J, Edwards RD, Ahmed SS. Neurocysticercosis: a case report and brief review. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2016;9(1):100–102. doi: 10.1016/j.apjtm.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The Lancet Infectious D. Treatment of neurocysticercosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(8):657. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70857-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garcia HH, Nash TE, Del Brutto OH. Clinical symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of neurocysticercosis. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(12):1202–1215. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70094-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ng-Nguyen D, Noh J, Breen K, Stevenson MA, Handali S, Traub RJ. The epidemiology of porcine Taenia solium cysticercosis in communities of the central highlands in Vietnam. Parasit Vectors. 2018;11(1):360. doi: 10.1186/s13071-018-2945-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carabin H, Traoré AA. Taenia solium Taeniasis and Cysticercosis control and elimination through community-based interventions. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2014;1(4):181–193. doi: 10.1007/s40475-014-0029-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ngowi H, Ozbolt I, Millogo A, Dermauw V, Somé T, Spicer P, Jervis LL, Ganaba R, Gabriel S, Dorny P, et al. Development of a health education intervention strategy using an implementation research method to control taeniasis and cysticercosis in Burkina Faso. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6(1):95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Mwape KE. Effectiveness of an education-based control option for human cysticercosis. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(4):e359–e360. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ngowi HA, Carabin H, Kassuku AA, Mlozi MR, Mlangwa JE, Willingham AL., 3rd A health-education intervention trial to reduce porcine cysticercosis in Mbulu District, Tanzania. Prev Vet Med. 2008;85(1–2):52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sarti E, Flisser A, Schantz PM, Gleizer M, Loya M, Plancarte A, Avila G, Allan J, Craig P, Bronfman M, et al. Development and evaluation of a health education intervention against Taenia solium in a rural community in Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;56(2):127–132. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the conclusions of this article are include within the article. Mr. Xin-Zhong Zang is the contact person for Availability of data and materials.