Abstract

Objectives

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) increases women’s susceptibility to sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV and may partly explain the high incidence of STI/HIV among girls and young women in East and southern Africa. The objectives of this study were to investigate the association between BV and sexual debut, to investigate other potential risk factors of BV and to estimate associations between BV and STIs.

Methods

Secondary school girls in Mwanza, aged 17 and 18 years, were invited to join a cross-sectional study. Consenting participants were interviewed and samples were obtained for STI and BV testing. Factors associated with prevalent BV were analysed using multivariable logistic regression. Y-chromosome was tested as a biomarker for unprotected penile-vaginal sex.

Results

Of the 386 girls who were enrolled, 163 (42%) reported having ever had penile-vaginal sex. Ninety-five (25%) girls had BV. The prevalence of BV was 33% and 19% among girls who reported or did not report having ever had penile-vaginal sex, respectively. BV was weakly associated with having ever had one sex partner (adjusted odds ratio (aOR) 1.59;95% CI 0.93 to 2.71) and strongly associated with two or more partners (aOR = 3.67; 95% CI 1.75 to 7.72), receptive oral sex (aOR 6.38; 95% CI 1.22 to 33.4) and having prevalent human papillomavirus infection (aOR = 1.73; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.95). Of the 223 girls who reported no penile-vaginal sex, 12 (5%) tested positive for an STI and 7 (3%) tested positive for Y-chromosome. Reclassifying these positive participants as having ever had sex did not change the key results.

Conclusions

Tanzanian girls attending school had a high prevalence of BV. Increasing number of sex partner was associated with BV; however, 19% of girls who reported no penile-vaginal sex had BV. This suggests that penile-vaginal sexual exposure may not be a prerequisite for BV. There was evidence of under-reporting of sexual debut.

Keywords: bacterial vaginosis, adolescent, Africa, women

Introduction

Globally, there are approximately 380 000 new HIV infections among girls and young women aged 10–24 years every year.1 In girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa, the high incidence of HIV cannot be fully explained by behavioural factors alone (eg, frequent partner exchange).2–4 Higher per-partnership transmission probability could be due to biological factors evidenced by high rates of HIV positivity following the first few episodes of sexual intercourse after sexual debut.3 One factor that may increase susceptibility to HIV is the presence of abnormal vaginal microbiota, including bacterial vaginosis (BV).

BV is particularly prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, with East African prevalences ranging from 21% to 34% among general population women.5 BV is associated with an increased risk of acquiring HIV infection in women.6 7 BV also increases the risk of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) including human papillomavirus (HPV) and herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) infection, which are in turn associated with HIV acquisition.8–11

The aetiology of BV is unclear, and the role of sexual transmission of BV-associated bacteria is an important unresolved question. Studies investigating BV around the time of sexual initiation may provide useful insight for understanding the aetiology of BV. Cross-sectional studies in the USA, Peru and Ecuador have documented BV among sexually naïve adolescents.12 13 Although a more recent cross-sectional study among young Australian women showed that BV was not detected among women without a history of sexual contact,14 a longitudinal study in the USA reported that colonisation with BV-associated bacteria was rare in sexually inexperienced women, apart from Gardnerella vaginalis, which was detected in 40% of participants at baseline. The initiation of penile-vaginal sex was associated with increased prevalence of G. vaginalis.15 Similarly, in a longitudinal study among school girls in Belgium, G. vaginalis and Atopobium vaginae were detected among some girls with no sexual experience (27% and 18%, respectively), and the initiation of sex was associated with increased presence of these BV-associated bacteria.16 The latter studies were carried out in populations with low BV and STI prevalence. More studies are needed to investigate BV among adolescent girls or young women around the time of their sexual debut in settings with high BV, STI and HIV prevalence. These studies should include other suggested risks for BV in the literature, including intravaginal practices, menstrual hygiene and tobacco use.6 17 18

We conducted a cross-sectional study among girls aged 17 and 18 years old attending secondary school in Mwanza, Tanzania to characterise the vaginal microbiota in girls who reported that they had never had sexual intercourse and girls who had passed their sexual debut. In this paper, we present the prevalence of BV, associated risk factors for BV and associations between BV and STIs. Previous research among girls in this region reported the median age of sexual debut to be 17 years.19

Methods

Study population and enrolment

Girls aged 16–18 enrolled in government-funded secondary day schools in Mwanza municipality were listed. Boarding schools were excluded because parents were not available to provide consent. Assuming that 50% of the girls reported sexual debut, a sample size of 400 was chosen to allow us to estimate the prevalence of BV with adequate precision in sexually active and sexually naïve girls. Recruitment was started in the schools with the highest numbers of pupils listed and continued till the sample size of 400 was reached.

Eligibility criteria included being aged 17 or 18 years old at enrolment, not having participated in a similar study, resident in Mwanza City and staying in Mwanza City for 1 month postenrolment to receive test results for STIs.

Study procedures

Eligible girls were asked for their written informed consent/assent (with written informed consent from parents/guardians if the girls were aged 17 years or oral consent if girls were aged 18 years) before being enrolled and interviewed in a central research clinic. Structured face-to-face interviews obtained data on sociodemographics, hygiene practices, drug and alcohol use, sexual behaviours and symptoms of STIs. Urine and blood samples were collected. Five self-administered vaginal swabs were collected from non-pregnant girls. Girls who wanted to know their HIV status were provided with voluntary counselling and testing using on-site rapid tests; girls who did not want to know their status had HIV rapid tests performed in the central laboratory.

Girls with vaginal discharge syndrome, genital ulcer disease or pelvic inflammatory disease were offered free syndromic management on the same day. Laboratory results for treatable STIs and free treatment as required were provided to participants within 2 weeks.

Laboratory methods

Laboratory testing was performed according to standard operating procedures. Urine samples were tested for pregnancy using the QuickVue+Test (QUIDEL, USA). Serum samples were used to test for IgG antibodies for HSV-2 by ELISA (Kalon Biological, UK). Syphilis was determined by the Immutrep Rapid Plasma Reagin test (Omega Diagnostics, Scotland) and the Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (SERODIA, Fujirebio, Japan).

All blood samples were screened with Determine HIV 1/2 rapid test (Alere, Japan). If reactive, they were tested with the Uni-Gold HIV rapid test (Trinity Biotech, Ireland). If both tests were reactive, the final result was deemed positive. If the Uni-Gold test was not reactive, the sample was tested with the HIV ½ Stat-Pak test (Chembio, USA). The final result was considered positive if the Stat-Pak result was reactive.

A vaginal swab was used to prepare a slide for Gram staining that was examined for vaginal yeast and for BV using the Nugent score.20 A Nugent score of 0–3 indicated normal microbiota, 4–6 indicated intermediate microbiota and 7–10 indicated BV. All slides were read by two trained technicians. In case of discordant results, the laboratory supervisor re-read the slide. The same swab was inoculated in an InPouch TV device (BioMed Diagnostics, USA) for Trichomonas vaginalis, incubated at 37°C, and read every other day for the presence of motile trichomonads for 5 days or until positive. Two flocked swabs (Copan, USA) were pooled and aliquots were tested for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium by in-house real-time PCR.21 22 HPV genotyping was performed using the Roche Linear Array HPV Genotyping Test (Roche, USA), which detect 37 HPV genotypes.

Swabs from participants who denied having passed their sexual debut were tested for Y-chromosome by in-house real-time PCR as a biomarker for recent unprotected penile-vaginal sex.23

Data management and statistical methods

Questionnaire data were double-entered into OpenClinica (Akaza Research, USA) and analysed using the SAS Software V.9.3 (SAS Institute, USA). We restricted the analyses to participants with Nugent score results.

Participant characteristics were examined by reported sexual debut status and by sociodemographic, behavioural and biological factors. Socioeconomic status (SES) was estimated using an indicator based on the type of possessions owned by the head of the household. BV prevalence was estimated separately for participants with and without a history of penile-vaginal sex. The infections investigated in this analysis were restricted to any positive HPV genotype, T. vaginalis and combined C. trachomatis and/or N. gonorrhoeae infection because of the relatively low prevalence of STIs found in this study.

We used logistic regression to estimate the effects of selected sociodemographic and behavioural risk factors on BV and summarised these in terms of crude and adjusted odds ratios (aORs) along with 95% CI and p values. The number and type of variables considered in this analysis were informed by causal associations found in the literature or potential confounders.

Using a hierarchical approach to the risk factor analysis, we first estimated the crude and independent effects of the sociodemographic characteristics on BV positivity (level 1). The independent effects were estimated using multivariable logistic regression adjusted for any other sociodemographic variables where p<0.10 in the adjusted analysis. This procedure was repeated for the analysis of behavioural risk factors (level 2), except that the multivariable model at this level was adjusted for other behavioural factors with adjusted associations with p<0.10 and the sociodemographic characteristics that were found to be independently associated with BV from the first stage of the analysis. Last, in a separate logistic regression analysis, we examined the associations between BV and prevalent STIs.

To investigate under-reporting of sexual behaviour, we carried out two sensitivity analyses. In the first analysis, we regrouped those participants who denied sexual activity but had a positive test for HSV-2, chlamydia, gonorrhoea, M. genitalium or Y-chromosome as sexually active and repeated the analysis described above. HPV and trichomoniasis were not included in this analysis as there is some evidence of non-sexual transmission for this infections,24 25 and HIV infection was not included as there was some evidence in the source notes that these were the result of vertical transmission. In the second sensitivity analysis, we used a more conservative approach and included all STIs (ie, including trichomoniasis, HPV and HIV) and Y chromosome.

Results

We identified 26 non-boarding schools with at least 25 girls in the target age group for inclusion in the study; all but two participated in the study. Recruitment of girls took place between November 2013 and June 2014.

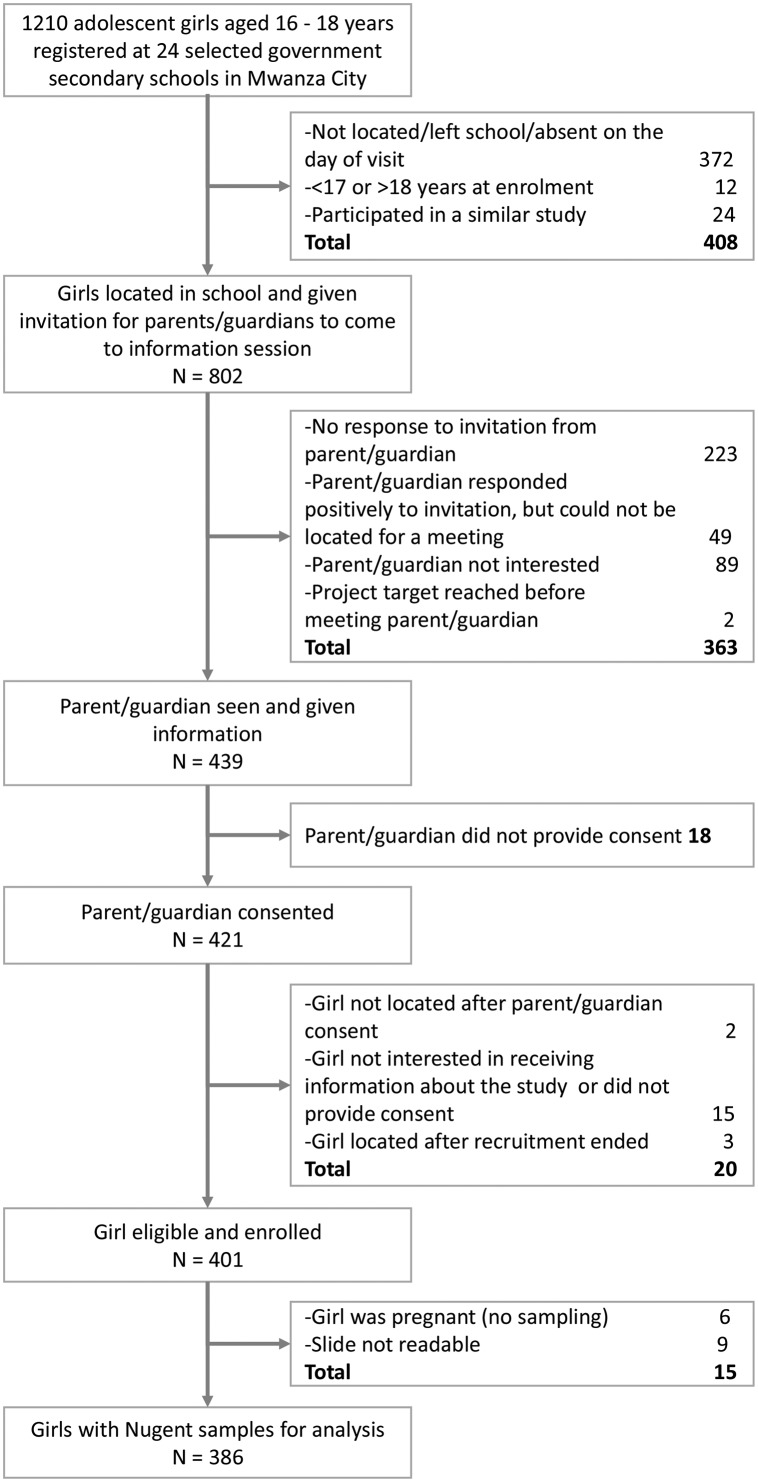

There were 1210 girls registered at the 24 participating schools who were aged 17 or 18 years (figure 1). Of these, 802 (66%) girls were successfully contacted at school and their parents were invited for a study information meeting and 55% (439) of parents attended. A total of 401 (95%) girls provided consent/assent and were enrolled in the study. Of these, 386 (96%) had a BV result and were included in the analyses.

Figure 1.

Recruitment procedure and derivation of the final analysis sample for 401 school girls enrolled in a cross-sectional study in Mwanza, Tanzania.

Participant characteristics

Over half of the participants were 17 years old (56%, table 1) and 75% were born in Mwanza region. Most girls lived in a household with at least their mothers (63%), but a substantial proportion reported not living with either of their parents (30%). Few girls reported spending at least one night away from home in the last 3 months (12%) or having ever drunk alcohol (3%). None reported smoking cigarettes or using illicit drugs.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics, reported sexual history and hygiene management and reproductive tract infections among adolescent school girls in Mwanza City, Tanzania

| Participant reported having had penile-vaginal sex | All | |||||

| Yes | No | |||||

| Total | 163 | 42% | 223 | 58% | 386 | 100% |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 17 | 80 | 49% | 135 | 61% | 215 | 56% |

| 18 | 83 | 51% | 88 | 39% | 171 | 44% |

| Born in | ||||||

| Mwanza region | 118 | 72% | 172 | 77% | 290 | 75% |

| Other region | 45 | 28% | 51 | 23% | 96 | 25% |

| Lives with | ||||||

| Mother (+/-father/other person) | 98 | 60% | 147 | 66% | 245 | 63% |

| Father (+/-other person, but not mother) | 12 | 7% | 12 | 5% | 24 | 6% |

| Does not live with mother or father | 53 | 33% | 64 | 29% | 117 | 30% |

| Number of people in household | ||||||

| 1–5 | 69 | 42% | 65 | 29% | 134 | 35% |

| 6–7 | 46 | 28% | 84 | 38% | 130 | 34% |

| 8 or more | 48 | 29% | 74 | 33% | 122 | 32% |

| SES indicator (possessions) | ||||||

| Car | 8 | 5% | 16 | 7% | 24 | 6% |

| TV, but no car | 76 | 47% | 89 | 40% | 165 | 43% |

| Cell phone, no car or TV | 73 | 45% | 110 | 49% | 183 | 47% |

| None of the above | 6 | 4% | 8 | 4% | 14 | 4% |

| Nights outside home, last 3 months | ||||||

| None | 138 | 85% | 202 | 91% | 340 | 88% |

| One or more | 25 | 15% | 21 | 9% | 46 | 12% |

| Hygiene behaviour | ||||||

| Menstrual hygiene management | ||||||

| Reusable cloth | 60 | 37% | 90 | 40% | 150 | 39% |

| Underpants | 161 | 99% | 211 | 95% | 372 | 96% |

| Sanitary pads | 133 | 82% | 149 | 67% | 282 | 73% |

| Tampons or toilet paper | 1 | 1% | 2 | 1% | 3 | 1% |

| Intravaginal cleansing | ||||||

| No cleansing | 121 | 74% | 207 | 93% | 328 | 85% |

| Plain water | 23 | 14% | 11 | 5% | 34 | 9% |

| Soap | 17 | 10% | 5 | 2% | 22 | 6% |

| Cloth, cotton wool, detergents | 2 | 1% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 1% |

| Method of cleaning after defecation | ||||||

| Water only | 149 | 91% | 193 | 87% | 342 | 89% |

| Toilet paper | 9 | 6% | 22 | 10% | 31 | 8% |

| Other | 5 | 3% | 8 | 4% | 13 | 3% |

| Direction of cleaning after defecation | ||||||

| Front to back | 118 | 72% | 176 | 79% | 294 | 76% |

| Back to front | 45 | 28% | 47 | 21% | 92 | 24% |

| Sexual behaviour | ||||||

| Touched penis with hands | 19 | 12% | 3 | 1% | 22 | 6% |

| Man/boy touched vagina with hands | 34 | 21% | 1 | 0% | 35 | 9% |

| Had penis in her mouth | 2 | 1% | 1 | 0% | 3 | 1% |

| Receptive oral sex | 8 | 5% | 1 | 0% | 9 | 2% |

| Penis rubbed against her genitals (without penetration) | 9 | 6% | 0 | 0% | 9 | 2% |

| Anal sex* | 2 | 1% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 1% |

| Number of life-time (penile-vaginal sex) partners | ||||||

| One | 123 | 75% | ||||

| Two | 31 | 19% | ||||

| Three or more | 9 | 6% | ||||

| Age of first sexual partner | ||||||

| <1 year older | 16 | 10% | ||||

| 1–2 years older | 31 | 19% | ||||

| 2–3 years older | 30 | 18% | ||||

| >3 years older | 64 | 39% | ||||

| Don’t know/no answer | 22 | 13% | ||||

| Frequency of condom use with current/latest partner | ||||||

| Never | 67 | 41% | ||||

| Some of the time | 24 | 15% | ||||

| Always | 69 | 42% | ||||

| Don’t know/no answer | 3 | 2% | ||||

| BV, vaginal yeast and sexually transmitted infections | ||||||

| BV (Nugent 7–10) | 53 | 33% | 42 | 19% | 95 | 25% |

| Intermediate (Nugent 4–6) | 17 | 10% | 12 | 5% | 29 | 7% |

| Vaginal yeast | 10 | 6% | 11 | 5% | 21 | 5% |

| Chlamydia trachomatis | 8 | 5% | 1 | 0% | 9 | 2% |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | 4 | 2% | 4 | 2% | 8 | 2% |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | 15 | 9% | 2 | 1% | 17 | 4% |

| Mycoplasma genitalium | 6 | 4% | 3 | 1% | 9 | 2% |

| Active syphilis | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Human papillomavirus—any genotype† | 84 | 52% | 41 | 18% | 125 | 33% |

| Herpes simplex virus-2 | 5 | 3% | 4 | 2% | 9 | 2% |

| HIV† | 0 | 0% | 3 | 1% | 3 | 1% |

*Missing data for one participant.

†Missing data for two participants.

BV, bacterial vaginosis; SES, socioeconomic status.

All girls in the study had passed menarche, and the median age of menarche was 14 (IQR 14–15). Girls reported using multiple types of menstrual hygiene products; the most common included underpants (96%), commercial sanitary pads (73%) and reusable cloth (39%). Only 15% reported intravaginal cleansing and this was more common among girls reporting penile-vaginal sex 26% vs 7%. Only one girl reported intravaginal insertion (insertion of lemon or lime juice). Almost all girls reported washing with water after defecation (99.5%); a few used toilet paper (8%) or another material (eg, cloth or leaves). Overall, 24% reported washing or wiping their vulva/perianal area from back to front after defecation.

All girls were unmarried. Of the 386 participants, 6% reported having touched a penis, 9% reported that a man or boy had touched her genitals, 1% reported having provided oral sex, 2% reported ever receiving oral sex from a male partner, 2% reported having a penis rub her genitals without penetration, 1% reported anal sex and 42% reported having penile-vaginal sex with at least one sex partner. Of those who reported penile-vaginal sex, 25% had more than one partner and 42% reported always using condoms with their last partner. There were only three girls who reported non-coital sexual exposures without penile-vaginal penetrative sex.

Prevalence of BV, vaginal yeast and STIs

The overall prevalence of BV was 25% (95/386), with 19% in girls who reported no penile-vaginal sex and 33% in girls reporting having had penile-vaginal sex (p=0.002, Pearson χ² test).

The prevalence of vaginal yeast was 5%. The overall HPV prevalence was 33% (125/384). The HPV prevalence among girls who reported and did not report penile-vaginal sex was 52% and 18%, respectively. The prevalence of T. vaginalis infection was 4%, and the prevalences of C. trachomatis, N. gonorrhoeae, M. genitalium were all 2%. HSV-2 seroprevalence was 2%, and HIV seroprevalence was 1%. There were no positive tests for syphilis.

Sexual debut and other potential risk factors associated with prevalent BV

Results from the analysis of sociodemographic and behavioural risk factors for BV are shown in table 2. There was modest evidence that lower SES was associated with BV. No other sociodemographic factors were associated with BV.

Table 2.

Prevalence of BV and associations with sociodemographic and behavioural determinants among adolescent school girls in Mwanza City, Tanzania

| N | BV n (%) |

OR (95% CI) |

P values | Adjusted OR (95% CI)§ | P values | |

| Total | 386 | 95 (25) | – | – | – | – |

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 17 | 215 | 55 (26) | 1 | 0.620 | 1 | 0.642 |

| 18 | 171 | 40 (23) | 0.88 (0.56 to 1.42) | 0.89 (0.56 to 1.43) | ||

| SES indicator (possessions)* | ||||||

| Car in household | 24 | 2 (8) | 0.70 (0.49 to 1.01) | 0.054 | 0.71 (0.49 to 1.01) | 0.054 |

| TV, but no car in household | 165 | 39 (24) | – | – | ||

| Cell phone, no car or TV in household | 183 | 49 (27) | – | – | ||

| None of the above | 14 | 5 (36) | – | – | ||

| Lives with | ||||||

| Mother (+/-father/other person) | 245 | 58 (24) | 1 | 0.843 | 1 | 0.564 |

| Father (+/-other person, but not mother) | 24 | 6 (25) | 1.08 (0.41 to 2.83) | 1.13 (0.42 to 3.00) | ||

| Does not live with mother or father | 117 | 31 (26) | 1.16 (0.70 to 1.93) | 1.33 (0.79 to 2.25) | ||

| Behavioural factors | ||||||

| Menstrual hygiene management† | ||||||

| Sanitary pads or towels | 203 | 52 (26) | 1 | 0.719 | 1 | 0.675 |

| Cloth, toilet paper or pants | 179 | 43 (24) | 0.92 (0.58 to 1.46) | 0.90 (0.55 to 1.47) | ||

| Intravaginal cleansing | ||||||

| No cleansing | 328 | 79 (24) | 1 | 0.594 | 1 | 0.565 |

| Using water only | 34 | 8 (24) | 0.97 (0.42 to 2.23) | 0.60 (0.24 to 1.53) | ||

| Using other substances | 24 | 8 (33) | 1.58 (0.65 to 3.82) | 0.91 (0.33 to 2.47) | ||

| Direction of cleaning after defecation | ||||||

| Front to back | 294 | 72 (24) | 1 | 0.921 | 1 | 0.906 |

| Back to front | 92 | 23 (25) | 1.03 (0.60 to 1.77) | 1.04 (0.59 to 1.82) | ||

| Man/boy touched vagina with hands | ||||||

| No | 351 | 81 (23) | 1 | 0.030 | 1 | 0.512 |

| Yes | 35 | 14 (40) | 2.22 (1.08 to 4.57) | 0.73 (0.29 to 1.85) | ||

| Receptive oral sex | ||||||

| No | 377 | 88 (23) | 1 | 0.003 | 1 | 0.028 |

| Yes | 9 | 7 (78) | 11.5 (2.35 to 56.3) | 6.38 (1.22 to 33.4) | ||

| Life-time sexual partners | ||||||

| None | 223 | 42 (19) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.002 |

| One | 123 | 33 (27) | 1.58 (0.94 to 2.66) | 1.59 (0.93 to 2.71) | ||

| Two or more | 40 | 20 (50) | 4.31 (2.13 to 8.72) | 3.67 (1.75 to 7.72) | ||

| Condom use with latest partner†,‡ | ||||||

| Always | 69 | 19 (28) | 1 | 0.306 | 1 | 0.553 |

| Not always | 91 | 32 (35) | 1.43 (0.72 to 2.82) | 1.25 (0.60 to 2.57) | ||

| Age of first sexual partner†,‡ | ||||||

| <1 year older | 16 | 5 (31) | 1 | 0.350 | 1 | 0.371 |

| 1–2 years older | 31 | 6 (19) | 0.53 (0.13 to 2.10) | 0.44 (0.10 to 1.88) | ||

| 2–3 years older | 30 | 11 (37) | 1.27 (0.35 to 4.64) | 1.22 (0.31 to 4.76) | ||

| 3 or more years older | 64 | 24 (38) | 1.32 (0.41 to 4.26) | 1.07 (0.32 to 3.67) | ||

*SES indicator was fitted as a continuous covariate; the OR of 0.70 estimates the decrease in odds of BV for a one-step increase in SES score.

†Missing data for some participants.

‡Analysis restricted to those who reported having had at least one partner.

§All were adjusted for age and SES; behavioural factors were also adjusted for lifetime sexual partners and oral sex.

BV, bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score ≥7); SES, socioeconomic status.

The number of life-time sexual partners was independently associated with BV (p=0.002) and participants reporting two or more sexual partners had 3.67 (95% CI 1.75 to 7.72 times the odds of BV compared with those who reported no past (penile-vaginal) sex partners. In addition, a higher proportion of girls who reported receiving oral sex from a male partner had BV 78% vs 23%), although numbers were low and CIs were wide (aOR=6.38; 95% CI 1.22 to 33.4). No other behaviours were independently associated with BV.

Associations between BV and other reproductive tract infections including STIs

HPV infection was independently associated with BV (aOR=1.73; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.95, table 3). Vaginal yeast, chlamydial and/or gonorrhoea (combined) and trichomoniasis were not associated with BV.

Table 3.

Associations between BV and sexually transmitted infections among adolescent school girls in Mwanza City, Tanzania

| N | BV n (%) |

OR (95% CI) |

P values | Adjusted OR (95% CI)† | P values | |

| Total | 386 | 95 (25) | – | – | – | – |

| Vaginal yeast | ||||||

| Negative | 365 | 92 (25) | 1 | 0.268 | 1 | 0.336 |

| Positive | 21 | 3 (14) | 0.50 (0.14 to 1.72) | 0.54 (0.15 to 1.91) | ||

| Chlamydia trachomatis or Neisseria gonorrhoea | ||||||

| Negative | 369 | 91 (25) | 1 | 0.916 | 1 | 0.542 |

| Positive | 17 | 4 (24) | 0.94 (0.30 to 2.96) | 0.68 (0.20 to 2.33) | ||

| Trichomonas vaginalis | ||||||

| Negative | 369 | 89 (24) | 1 | 0.300 | 1 | 0.935 |

| Positive | 17 | 6 (35) | 1.72 (0.62 to 4.78) | 0.95 (0.31 to 2.92) | ||

| Human papillomavirus* | ||||||

| Negative | 259 | 50 (19) | 1 | <0.001 | 1 | 0.042 |

| Positive for any genotype | 125 | 45 (36) | 2.35 (1.46 to 3.79) | 1.73 (1.02 to 2.95) | ||

*Data missing for two participants in the BV negative group.

†All adjusted for age, SES, lifetime sexual partners, receptive oral sex and HPV.

BV, bacterial vaginosis (Nugent score ≥7); HPV, human papillomavirus; SES, socioeconomic status.

Sensitivity analysis

A total 19 (9%) of the 223 participants who reported no penile-vaginal sex, tested positive for HSV-2, chlamydia, gonorrhoea, M. genitalium (n=12) or Y-chromosome (n=7). For the second sensitivity analysis, 56 (25%) tested positive for any STI (including HPV, trichomoniasis and HIV) and Y-chromosome. Positive tests were reclassified as having had sex for the first and second sensitivity analyses. Using these classifications, the prevalence of BV among those who had not passed their sexual debut was 20% (40/204) and 16% (26/167) in the first and second sensitivity analyses, respectively. The estimated ORs were similar to those derived from the main analysis (online supplementary material 1).

sextrans-2018-053680supp001.docx (43.2KB, docx)

Discussion

We found a high prevalence of BV among girls around the age or expected age of sexual debut. Increasing number of lifetime partners was strongly associated with BV. However, a substantial proportion of girls who denied penile-vaginal intercourse were diagnosed with BV. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to investigate BV among girls or young women in sub-Saharan Africa around their sexual debut. Given the known association between BV and HIV, and the high burden of HIV among girls and young women, the high prevalence of BV is of public health concern.

The strong associations between BV, number of lifetime sex partners, oral sex and HPV are consistent with the literature. Fethers and colleagues found an association between new or multiple partners and BV in a meta-analysis (pooled RR:1.6; 95% CI 1.5 to 1.8).26 Several studies report an association between receiving oral sex and BV.14 27 28 While the literature shows strong associations between BV and prevalent bacterial and viral STIs,8–11 we only saw an association with prevalent HPV infection. However, this may be due to the low prevalence of other STIs in this study.

Our study strongly suggests that penile-vaginal sex increases the risk for BV; however, there is also evidence that it may not be a prerequisite for BV. This is consistent with past cross-sectional studies which reported BV among sexually naïve adolescents.12 13 More recent studies in populations with low BV prevalence have shown that BV has not been detected among women without a history of coital or non-coital sexual contact.14 15 In our study, only 3 (1%) girls who reported not having penile-vaginal sex, reported non-coital sexual exposure. While our results imply that girls and young women in sub-Saharan Africa may experience BV prior to sexual debut, these results must be considered in the context of under-reporting of sexual behaviours. We found several cases of STIs and detected Y-chromosome among girls who did not report penile-vaginal sex. Under-reporting of sexual behaviour among adolescents has been well documented internationally especially during face-to-face interviews29 and has also been documented in Tanzania.25 30 Although the study staff emphasised confidentiality of results to both parents and participants, students may have feared stigmatisation, school expulsion and physical punishment.25 Additionally, we did not ask about female sexual contacts or sexual assault among those girls who denied penile-vaginal sex. We carried out two sensitivity analyses to address reporting bias by reclassifying those in the sexually naïve group with STIs or Y-chromosome and found no substantial differences in the results in both analyses. However, this approach is unsatisfactory as it only redresses a proportion of the reporting bias. Reporting bias of sexual behaviour represents major impediment for the fields of adolescent health and HIV/STI prevention. Better methods of estimating reporting bias for sensitive behavioural data are needed. In addition, longitudinally designed research is needed to better understand changes in the vaginal microbiota before and after sexual debut.

The overall HPV prevalence was high (33%), with 52% and 18% prevalence among girls reporting and not reporting penile-vaginal sex, respectively. Houlihan and colleagues reported an overall HPV prevalence of 8% among girls who reported never having penile-vaginal sex and 32% among girls who had passed sexual debut in a similar population in Mwanza Tanzania.25 Conversely, the HSV-2 prevalence was lower than expected. Past studies from this region using the same laboratory test have shown higher prevalence of HSV-2, increasing rapidly after sexual debut; in 1999, Obasi and colleagues found an HSV-2 prevalence of 18%, 22% and 33% among 15, 16 and 17 year olds, respectively.31

This study had several strengths. We asked detailed information about behaviour and experiences of first sex and were able to measure STIs and HIV among girls recruited from a school setting. However, there were several limitations in addition to the issue of reporting bias noted above. This is a cross-sectional study and, therefore, the direction of causality cannot be discerned, most relevant for the association between BV and STIs. Also, we enrolled 401 girls from a list of 1210 (34%), which suggests possible selection bias. Most of the girls not enrolled were either not found at school or the parent was not available or willing to provide consent—these girls may be at higher risk for STI and BV, therefore we may have underestimated the prevalence of STIs and BV.

In conclusion, a high prevalence of BV and HPV was found among adolescent girls attending secondary schools in Tanzania. Penile-vaginal sex and increasing number of partners appear to increase the risk for BV, yet there is some evidence that girls may be entering sexual debut with altered vaginal microbiota, placing them at risk for HIV. Importantly, there was strong evidence of under-reporting of sexual activity in this population, and further methodological studies are needed to investigate improved reporting for sexual behaviour in adolescent populations. Longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the dynamics of vaginal microbiota during this crucial time of sexual transition in high HIV prevalence settings.

Key messages.

Tanzanian girls attending school had a high prevalence of bacterial vaginosis (BV) (25%).

Sexual debut and increasing number of sex partners was associated with BV; however, 19% of girls who reported no penile-vaginal sex had BV.

There was strong evidence of under-reporting of sexual activity in this population, and further methodological studies are needed to investigate improved reporting for sexual behaviour in adolescent populations.

Longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the dynamics of vaginal microbiota during this crucial time of sexual transition in high HIV prevalence settings.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the parents and participants who gave up their time and provided samples for this study and to our dedicated study nurses and clinical officers for implementing the study. We also thank the laboratory and data teams and the administrative and support staff at the Mwanza Interventional Trials Unit, National Institute for Medical Research, the Institute of Tropical Medicine and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine for their

contributions.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Jackie A Cassell

Contributors: Conception or design of the work: AB, DW-J, JC, SN, TC, KB, SCF, AA, VJ, RJH. Data collection: JI, SN, AA. Data analysis and interpretation: CHH, KB, RJH, SCF, AB. Drafting the article: SCF, AB, CHH. Critical revision of the article: SCF, AB, CHH, TC, RJH, DW-J. Final approval of the version to be published: AB, DW-J, SN, RJH, JC, TC, VJ, KB, AA, JI, CHH, SCF.

Funding: Financial support for this study was provided by the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (project code: SP.2011.41304.066). Additionally, SCF (G1002369), KB and RJH (G0700837) received salary support through MRC/DFID.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp (867/13), the Ethics Committee of the University Teaching Hospital in Antwerp (13/14/147), the Lake Zone Institutional Review Board in Mwanza (MR/53/100/86) and the National Ethics Committee of the NIMR Coordinating Committee in Dar es Salaam (NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol.IX/1544) approved the study protocol.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. UNAIDS The gap report. 2014. Available http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf

- 2. Pettifor AE, Hudgens MG, Levandowski BA, et al. Highly efficient HIV transmission to young women in South Africa. AIDS 2007;21:861–5. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3280f00fb3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glynn JR, Caraël M, Auvert B, et al. Why do young women have a much higher prevalence of HIV than young men? A study in Kisumu, Kenya and Ndola, Zambia. AIDS 2001;15(Suppl 4):S51–S60. 10.1097/00002030-200108004-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Auvert B, Ballard R, Campbell C, et al. HIV infection among youth in a South African mining town is associated with herpes simplex virus-2 seropositivity and sexual behaviour. AIDS. 2001;15:885–98. 10.1097/00002030-200105040-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kenyon C, Colebunders R, Crucitti T. The global epidemiology of bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2013;209:505–23. 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Low N, Chersich MF, Schmidlin K, et al. Intravaginal practices, bacterial vaginosis, and HIV infection in women: individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Med 20112011;8:e1000416 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Buvé A, Jespers V, Crucitti T, et al. The vaginal microbiota and susceptibility to HIV. AIDS 2014;28:2333–44. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wiesenfeld HC, Hillier SL, Krohn MA, et al. Bacterial vaginosis is a strong predictor of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36:663–8. 10.1086/367658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Balkus JE, Richardson BA, Rabe LK, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and the risk of trichomonas vaginalis acquisition among HIV-1-negative women. Sex Transm Dis 2014;41:123–8. 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cherpes TL, Meyn LA, Krohn MA, et al. Association between acquisition of herpes simplex virus type 2 in women and bacterial vaginosis. Clin Infect Dis 2003;37:319–25. 10.1086/375819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. King CC, Jamieson DJ, Wiener J, et al. Bacterial vaginosis and the natural history of human papillomavirus. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2011;2011:1–8. 10.1155/2011/319460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bump RC, Buesching WJ. Bacterial vaginosis in virginal and sexually active adolescent females: evidence against exclusive sexual transmission. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988;158:935–9. 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90097-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yen S, Shafer MA, Moncada J, et al. Bacterial vaginosis in sexually experienced and non-sexually experienced young women entering the military. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102(5 Pt 1):927–33. 10.1016/S0029-7844(03)00858-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fethers KA, Fairley CK, Morton A, et al. Early sexual experiences and risk factors for bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis 2009;200:1662–70. 10.1086/648092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mitchell CM, Fredricks DN, Winer RL, et al. Effect of sexual debut on vaginal microbiota in a cohort of young women. Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:1306–13. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31827075ac [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jespers V, Hardy L, Buyze J, et al. Association of sexual debut in adolescents with microbiota and inflammatory markers. Obstet Gynecol 2016;128:22–31. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nelson TM, Borgogna JC, Michalek RD, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with an altered vaginal tract metabolomic profile. Sci Rep 2018;8:1–13. 10.1038/s41598-017-14943-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Das P, Baker KK, Dutta A, et al. Menstrual hygiene practices, WASH access and the risk of urogenital infection in women from Odisha, India. PLoS One 2015;10:e0130777–16. 10.1371/journal.pone.0130777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Doyle AM, Ross DA, Maganja K, et al. Long-term biological and behavioural impact of an adolescent sexual health intervention in Tanzania: follow-up survey of the community-based MEMA kwa Vijana Trial. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000287 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol 1991;29:297–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen CY, Chi KH, Alexander S, et al. A real-time quadriplex PCR assay for the diagnosis of rectal lymphogranuloma venereum and non-lymphogranuloma venereum Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Sex Transm Infect 2008;84:273–6. 10.1136/sti.2007.029058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hopkins MJ, Ashton LJ, Alloba F, et al. Validation of a laboratory-developed real-time PCR protocol for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in urine. Sex Transm Infect 2010;86:207–11. 10.1136/sti.2009.040634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jacot TA, Zalenskaya I, Mauck C, et al. TSPY4 is a novel sperm-specific biomarker of semen exposure in human cervicovaginal fluids; potential use in HIV prevention and contraception studies. Contraception 2013;88:387–95. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crucitti T, Jespers V, Mulenga C, et al. Non-sexual transmission of Trichomonas vaginalis in adolescent girls attending school in Ndola, Zambia. PLoS One 2011;6:e16310 10.1371/journal.pone.0016310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Houlihan CF, de Sanjosé S, Baisley K, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in adolescent girls before reported sexual debut. J Infect Dis 2014;210:837–45. 10.1093/infdis/jiu202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fethers KA, Fairley CK, Hocking JS, et al. Sexual risk factors and bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:1426–35. 10.1086/592974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tabrizi SN, Fairley CK, Bradshaw CS, et al. Prevalence of Gardnerella vaginalis and Atopobium vaginae in virginal women. Sex Transm Dis 2006;33:663–5. 10.1097/01.olq.0000216161.42272.be [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schwebke JR, Richey CM, Weiss2 HL. Correlation of behaviors with microbiological changes in vaginal flora. J Infect Dis 1999;180:1632–6. 10.1086/315065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Langhaug LF, Sherr L, Cowan FM. How to improve the validity of sexual behaviour reporting: systematic review of questionnaire delivery modes in developing countries. Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:362–81. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02464.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Upchurch DM, Lillard LA, Aneshensel CS, et al. Inconsistencies in reporting the occurence and timing of first intercourse among adolescents. J Sex Res 2002;39:197–206. 10.1080/00224490209552142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Obasi A, Mosha F, Quigley M, et al. Antibody to herpes simplex virus type 2 as a marker of sexual risk behavior in rural Tanzania. J Infect Dis 1999;179:16–24. 10.1086/314555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

sextrans-2018-053680supp001.docx (43.2KB, docx)