Abstract

In 2017, the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation published its official document detailing standards and core components for cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation. Building on the success of previous editions of this document (published in 2007 and 2012), the 2017 update aims to further emphasise to commissioners, clinicians, politicians and the public the importance of robust, quality indicators of cardiac rehabilitation (CR) service delivery. Otherwise, its overall aim remains consistent with the previous publications—to provide a precedent on which all effective cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation programmes are based and a framework for use in assessment of variation in service delivery quality. In this 2017 edition, the previously described seven standards and core components have both been revised to six, with a greater focus on measurable clinical outcomes, audit and certification. The principles within the updated document underpin the six-stage pathway of care for CR, and reflect the extensive evidence base now available within the field. To help improve current services, close collaboration between commissioners and CR providers is advocated, with use of the CR costing tool in financial planning of programmes. The document specifies how quality assurance can be facilitated through local audit, and advocates routine upload of individual-level data to the annual British Heart Foundation National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation, and application for national certification ensuring attainment of a minimum quality standard. Although developed for the UK, these standards and core components may be applicable to other countries.

Keywords: cardiac rehabilitation, cardiac risk factors and prevention

Introduction

This paper summarises the key points of the third most recent edition of the standards and core components for cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation which were published by the British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (BACPR) in 20 17.1 Earlier editions of this publication were produced by the BACPR in 20072 and 2012.3 4 This paper presents the current evidence base for cardiac rehabilitation (CR), and focuses specifically on those recommendations within the 2017 publication which are new, or which have been updated from the previous 2012 edition of the document.3 4 The full 2017 edition1 can be accessed from www.bacpr.com.

Building on success of the 2007 and 2012 publications,2–4 the aim of the 2017 update was to further emphasise to commissioners, clinicians, politicians and the public the importance of robust, quality indicators of CR service delivery. Otherwise, its overall aim remains consistent with the previous publications2–4—to provide a precedent on which all effective cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation programmes (CPRP) are based and a framework for use in assessment of variation in service delivery quality. To support implementation of these standards and core components, the BACPR has developed online educational modules, also available from www.bacpr.com.

The compelling case for cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation

As will be discussed throughout, CR has a robust evidence base reducing mortality and morbidity, reducing healthcare costs and enhancing the quality and productivity of people’s lives. It provides strong rationale for the evolution of current services to include an ever-expanding spectrum of patients—from those with established cardiovascular disease (CVD) to those who are asymptomatic but at high risk of future adverse cardiovascular events.5 6 Impacting favourably on cardiovascular mortality, acute hospitalisation, cardiorespiratory fitness and perceived healthy-related quality of life (QoL), CPRPs can facilitate early return to work and aid development of self-management skills.7–11

Completing a CPRP after myocardial infarction (MI) and/or coronary revascularisation significantly reduces emergency hospital admissions (from 30.7% to 26.1%; number needed to treat (NNT) 22), highlighting CR’s overall cost-efficacy.8 12 Furthermore, there is an absolute risk reduction in cardiovascular mortality (from 10.4% to 7.6%), compared with those who do not attend (NNT 37).8 Research suggests that CR does not affect rates of recurrent MI and repeat revascularisation, and its effect on all-cause mortality in congenital heart disease (CHD) is equivocal.13 However, recent work has shown that CPRPs which are able to prescribe cardioprotective medications, and which intensively manage six risk factors or more, can reduce all-cause mortality and recurrent MI.14 Certainly, mortality should not be considered the only measure of CR’s effectiveness. While optimal medical therapy and percutaneous intervention for management of CHD add ‘years to life’, the potential for CR to add ‘life to years’ should not be underestimated, and there is growing recognition that promotion of CR should focus on its ability to provide cost-effective and cost-saving secondary CVD prevention.15 Furthermore, those who have participated in CR after MI have shown significantly better adherence to their cardioprotective medications.16

Notably, for those with heart failure (HF), CR reduces hospitalisation, with a 25% relative risk reduction in overall emergency admissions and a 39% reduction (NNT 18) in acute HF-related episodes.17 In this group, deterioration and readmission have a hugely detrimental impact on QoL, associated morbidity and financial impact.

As centre-based and home-based CR do not appear to generate different outcomes, or incur substantially different healthcare costs, the CR setting can be individually tailored to patients’ preferences. In some cases, home-based CR has demonstrated a higher utilisation rate (uptake, adherence and completion)—therefore, services have the opportunity for innovative delivery to enhance patient recruitment.18–21 There is continued emphasis on the importance of early CR—which is both safe and feasible, and improves patient uptake and adherence.21–28 If a CR clinician engages with a patient in an acute hospital setting, and begins to undertake personalised goal setting at this point, then this may lead to higher uptake.25 29

Patients with other non-infectious diseases, particularly those with chronic respiratory conditions and certain forms of cancer, may also benefit from CR.30 31 Thus, there is an opportunity to further expand the scope and influence of prevention and rehabilitation services which may, in turn, release financial resources to enable more cost-effective deployment of staff and facilities.32

Given its clinical and cost-effectiveness for CVD management, it is imperative that structures are in place to maximise CR uptake, adherence and completion. The 2017 British Heart Foundation (BHF) National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation (NACR) reported that overall mean uptake to CR in the UK has reached 51% (of all eligible patients), which brings the UK’s uptake into the top 2% of countries in Europe.33 Although these data represent a steady increase in uptake, a modelling study conducted by the National Health Service (NHS) Improvement in 2013 advocated that increasing uptake of CR to 65% of all eligible individuals in England would reduce emergency cardiac admissions by 30%, releasing more than £30 million per year into the NHS, which could be used within rehabilitation and re-enablement.32

CR pathway of care

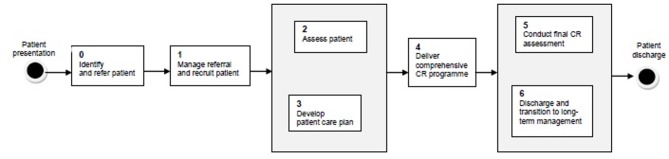

These 2017 standards and core components provide detail to complement the CR six-stage pathway of care set out by the Department of Health Commissioning Guide34 which encompasses patient presentation (eg, diagnosis or cardiac event), ascertaining eligibility, referral and assessment, through to long-term management (figure 1). There is recognition that each stage of the pathway is essential to ensure programme uptake and adherence, attainment of meaningful clinical outcomes and long-term behaviour change and improvement in health. Although designed for England, the pathway is pertinent to all four UK nations, and like the standards and core components, its basic principles should apply to other countries with state-funded health services.

Figure 1.

Department of Health commissioning guide six-stage patient pathway of care.34 CR, cardiac rehabilitation.

National and local factors for assuring quality

Quality assurance within CR is facilitated through an alliance both at local (eg, commissioners, CPRP teams) and national levels, together with contribution to the NACR and achievement of national certification. In 2016, a joint National Certification Programme for Cardiac Rehabilitation (NCP_CR) was launched by the BACPR and NACR. CPRPs should ultimately strive to attain the NCP_CR, which has been designed to demonstrate that programmes are meeting (or working towards) a set of quality standards, which are reflective of data submitted to the NACR, and adapted from those described within this document.1 35 The new approach is for all CPRPs to submit current NACR data sets and complete the NACR staff survey, http://www.cardiacrehabilitation.org.uk/NCP-CR.htm

BACPR standards and core components

In contrast to the 20123 4 edition of this document, which included seven standards and seven core components, this 2017 revision has six standards and six core components, with greater emphasis on quantifiable clinical and health outcomes, audit and certification.1

Standards of care

Two of the updated standards of care (Standard One and Standard Six; table 1) emphasise the importance of the administrative aspects of CPRPs, while the other four are centred on patient participation in terms of recruitment, assessment and clinical outcomes.1 In the 20123 4 edition, there was a standard dedicated to the establishment of a CR business case and budget. Although not included in the 2017 version as a standard, there is updated guidance on developing costing within business cases for CPRPs.1 The wording within the new standards has also been revised to clarify the strength of recommendations: ‘shall’ is used to convey a requirement with which all programmes are expected to comply (grade A/B recommendations based on the highest quality evidence available and recognised as best practice), while ‘should’ expresses a desirable recommendation (grade C/D recommendation).1

Table 1.

The six standards for cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation1

| The standards | |

| Standard One | The delivery of six core components by a qualified and competent multidisciplinary team, led by a clinical coordinator. |

| Standard Two | Prompt identification, referral and recruitment of eligible patient populations. |

| Standard Three | Early initial assessment of individual patient needs which informs the agreed personalised goals that are reviewed regularly. |

| Standard Four | Early provision of a structured cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation programme (CPRP), with a defined pathway of care, which meets the individual’s goals and is aligned with patient preference and choice. |

| Standard Five | On programme completion, a final assessment of individual patient needs and demonstration of sustainable health outcomes. |

| Standard Six | Registration and submission of data to the National Audit for Cardiac Rehabilitation (NACR) and participation in the National Certification Programme for Cardiac Rehabilitation (NCP_CR). |

Previously, the first standard specified that each CPRP should deliver the core components to ensure clinically effective care and sustainable health outcomes, while the second described the skill set of the multidisciplinary team required to achieve this.2–4 As these standards complement each other, they have been amalgamated in the 2017 version.1 The revised Standard One also specifies that there shall be inclusion of dedicated administrative support and involvement of a physician with sufficient knowledge of, interest in and dedication to cardiovascular rehabilitation and prevention.1

While the 20123 4 edition listed patient groups with CVD who should be offered CR, Standard Two within the 2017 version explicitly outlines priority groups that shall be offered CR in the first instance (eg, dependent on local policy/resources), and groups to which programmes ‘should aim to offer’ CR due to the known benefit1 (Table 2). There is emphasis that appropriately resourced CPRPs should demonstrate ambition to broaden access to provide high-quality and cost-effective input to those with established CVD and those with high CVD risk.1 Acknowledging the importance of early intervention, there are specified time frames for referral/recruitment, and the standard states that CPRPs shall receive the referral of an eligible either during the hospital stay or within 24 hours of discharge, or within 72 hours of an outpatient being identified as eligible.1

Table 2.

The six standards for cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation1

| Standard Two—Patient identification |

| Priority patient groups that shall be offered a cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation programme (CPRP): |

|

| Other patients known to benefit: |

|

While it was previously recommended that the initial CR assessment is undertaken and programme commenced ‘ideally within two weeks’,2–4 the updated Standard Three and Standard Four specify that these shall take place within 10 working days of referral, and if the assessment cannot be fully completed, this shall not prevent assessment of the remaining aspects or initiation of a formal CPRP.1 Furthermore, where commencement of group-based exercise has to be postponed, this shall not delay initiating care in relation to other relevant core components.1 In this respect, offering alternatives such as home-based CR with an evidence base allows flexibility and patient choice.8

The updated Standard Four also states that patients shall have access to the multidisciplinary team as required and shall be supported to undertake an individualised, structured exercise programme at least two to three times weekly, specifically designed to increase physical fitness.1 There is recognition that this requires documented evidence of regular review, goal setting and training progression, and there shall be documented communication between the patient and the team for at least 8 weeks.1

While the 20123 4 edition did not include a standard dedicated to reassessment, in this 2017 document,1 Standard Five ensures that patients have achieved sustainable outcomes on completion of the CPRP. The standard states that a final assessment shall be undertaken which revisits lifestyle risk-related factors, psychosocial health and medical risk management to identify the patient’s health outcomes, unmet goals and new or evolving clinical issues and to formulating long-term strategies.1 Data from the final assessment should be formally documented for audit and evaluation and shared with the patient and his/her patient’s primary care provider (and the referral source, where relevant) within 10 days of programme completion.1

In addition to re-emphasising the importance of national audit and evaluation by stating that CPRPs shall register and routinely submit individual-level baseline and reassessment data on clinical outcomes, and patient experience and satisfaction to the NACR, Standard Six includes a recommendation that every CPRP should strive to meet and maintain requirements for the NCP_CR.1

Core components

The BACPR’s core components for CR represent the ‘coordinated sum of activities required to influence favourably the underlying cause of cardiovascular disease, as well as to provide the best possible physical, mental and social conditions, so that the patients may, by their own efforts, preserve or resume optimal functioning in their community and through improved health behaviour, slow or reverse progression of disease’.1 This 2017 publication1 includes six core components (table 3) rather than the seven of the 20123 4 edition, with ‘medical risk management’ a new single core component that reflects the difficulty of disentangling the interplay between cardioprotective therapies and medical risk factors, given that drugs used to modify risk factors are also cardioprotective. Aside from this amalgamation, there are only minor updates, reflective of updates to the evidence base since the last edition was published.

Table 3.

The six core components for cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation1

| The six core components | |

| Health behaviour change and education | Health behaviour change Education |

| Lifestyle risk factor management | Physical activity and exercise Healthy eating and body composition Tobacco cessation and relapse prevention |

| Psychosocial health | |

| Medical risk management | |

| Long-term strategies | Patient responsibilities Service responsibilities |

| Audit and evaluation | |

Adoption of healthy behaviours and development of self-management skills remains the foundation of long-term cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation, and health behaviour change and education remains fundamental to all other components of CPRP.1 In this updated document, there is recognition that the educational component should take account of different learning styles, should be tailored to individual learning needs and should use best available resources (in different formats, using plain language and clear design) to enable patients to learn about their condition and management.1

In addition to increasing physical fitness and overall daily energy expenditure, the updated lifestyle risk factor management component states that an additional aim of physical activity and exercise training is to decrease sedentary behaviour.1 There is a focus on healthy eating and body composition as opposed to ‘diet’, and a new recommendation that patients with more complex dietary needs should be under care of a registered dietitian.1 There is also inclusion of bariatric surgery as a potential specialist intervention strategy to comanage weight loss.1 Acknowledging that the harmful effects of tobacco extend beyond cigarette smoking, there is focus on tobacco (rather than smoking) cessation, and greater emphasis on assessing and addressing tobacco use by others within the home.1 The component states that patient choice is a priority when selecting a tobacco cessation method, and recognises that, with a growing evidence base for their efficacy, e-cigarettes should be considered.1

In assessment of psychosocial health, this 2017 document1 provides specific examples of tools for measuring psychological distress (eg, anxiety and depression, using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) and QoL (eg, using the Dartmouth Primary Care Cooperative or Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire) and specifies that, in addition, patients should be assessed for psychological stressors, adequacy of social support and alcohol and substance misuse. There is greater detail on when ‘in house’ psychological support or intervention can be provided to patient, and when there should be referral to external appropriately trained psychological practitioners. There is emphasis that CPRPs should be aware of patients’ alcohol or substance misuse, and should offer onward referral to an appropriate resource if needed.1 The importance of identification and management (including onward referral, where required) of concerns or issues with sexual health or function is also highlighted.1

Although most of the new medical risk management component contains the detail of the previous two components that have been combined, there is additional emphasis on erectile dysfunction (ED). Highlighting that ED can be multifactorial in CVD, with medication, vascular disease and psychogenic factors all potentially contributing, the document states that patients with ED should be considered for medication review and appropriate onward referral where indicated.1

Within long-term strategies (previously entitled ‘long-term management’), it is noted that, in addition to local community support groups, patients’ ongoing self-management approaches could include online tools/applications and self-monitoring resources.1 The component states that patients should be supported by partnership between primary and secondary care services to provide self-management strategies to help the transition from CPRP and continue to minimise the risk of long-term CVD progression.1 Patients should be listed on GP Practice CHD/CVD registers.1

In this document,1 there is more detailed rationale for providing, and guidance on collecting, audit and evaluation data through NACR. Specifically, it states that, through the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the NHS and its services are required to offer CR to all eligible patients. With this, there is a duty to audit local performance and supply data to ensure national parity of service delivery.36 Furthermore, although CR uptake is improving, service quality is not equitable across the UK.36

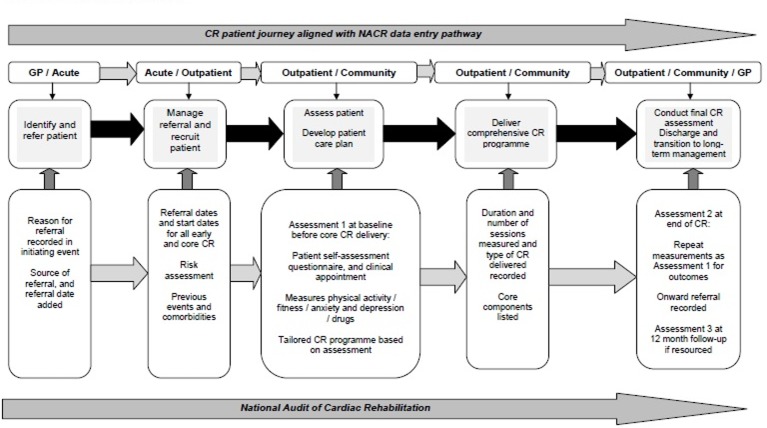

This component outlines that audit can be done directly via NACR or through data upload from local provider software. Data entered directly or uploaded to NHS Digital (the organisation that hosts NACR data) should include both individual and service-level data based on assessment and including outcomes.1 Where resources and service design permits, CPRPs are encouraged to provide 1-year follow-up data, which can be carried out within the NHS Digital-NACR software integrated with the patient journey, without duplication of work (figure 2).1

Figure 2.

Cardiac rehabilitation patient pathway aligned with National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation (NACR) data entry pathway.1 35 CR, cardiac rehabilitation; GP, general practitioner.

The 2017 standards and core components align with data requirements for the NCP_CR, and this component stresses that the BACPR advocates that all programmes submit data and register for the NCP_CR so that patients, wherever they are in the UK, can be sure that the CPRP available to them meets agreed minimum standards.1

Funding

Monitor (a part of NHS Improvement) recommends the CR costing tool to enable CPRPs to generate the costs per staff profile required to meet the needs of its patient population.37 38 As this only considers staff costs over 16 one-hour sessions, CPRPs will need to add other capital and services costs and alter according to the number of sessions they run. The 2017 revised standards and core components place equivalent emphasis on lifestyle risk factor management, psychosocial health and medical risk factor management, while placing health behaviour change and education at the centre of this care. Therefore, costing developed within business cases and/or locally determine funding will need to reflect the expertise and time required for qualified and competent practitioners to apply an evidence-based approach across the six-stage pathway of CR (figure 1).

Summary

In 2017, the BACPR published the third edition of its standards and core components for cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation. Earlier editions of this publication were produced in 20072 and 2012.3 4 The aim of the 2017 update was to further emphasise to commissioners, clinicians, politicians and the public the importance of robust, quality indicators of CR service delivery. While the 20123 4 edition of this document detailed seven standards and seven core components, the 2017 revision has six standards and six core components, with greater emphasis on quantifiable clinical and health outcomes, audit and certification.1

In working to build on the already extensive evidence base for CR, and expand the influence of prevention and rehabilitation services, innovative practice and close working between providers and commissioners is required. This should be done using the principles set out within this document as the precedent on which all effective CPRPs are designed, underpinned by the framework of the CR six-stage pathway of care. Online educational modules are available to support implementation of the document. The CR costing tool should be used in financial planning of CPRPs, with quality assurance facilitated through local audit of performance, participation in the BHF NACR and ultimately attainment of national certification. Although developed for the UK, these standards and core components may apply equally to CPRPs in other countries.

Acknowledgments

We thank the BHF for their continued support of the NACR and the ongoing partnership working with the BACPR in improving services for the benefit of all patients with CVD.

Footnotes

Contributors: The writing of this paper was coordinated by the main author, AC, supported by HD. Jemma Lough provided additional support as a technical editor of the paper. All of the other authors were part of a ’Standards and Core Components Primary Writing Group', which was co-ordinated by JM. All listed authors contributed to the original version of this manuscript, and to the revisions that were undertaken.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. The BACPR standards and core components for cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation 2017. 3rd edn London: BACPR, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. British Association for Cardiac Rehabilitation. Standards and core components for cardiac rehabilitation 2007. 1st edn London: BACR, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3. British Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. The BACPR standards and core components for cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation. 2nd edn London: BACPR, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Buckley JP, Furze G, Doherty P, et al. BACPR scientific statement: British standards and core components for cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation. Heart 2013;99:1069–71. 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-303460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stone JA, Fitchett D, Grover S, et al. Vascular protection in people with diabetes. Can J Diabetes 2013;37 Suppl 1:S322 10.1016/j.jcjd.2013.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dasgupta K, Quinn RR, Zarnke KB, et al. The 2014 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for blood pressure measurement, diagnosis, assessment of risk, prevention, and treatment of hypertension. Can J Cardiol 2014;30:485–501. 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anderson L, Thompson DR, Oldridge N, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016:CD001800 10.1002/14651858.CD001800.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dalal HM, Doherty P, Taylor RS. Cardiac rehabilitation. BMJ 2015;351:h5000 10.1136/bmj.h5000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rauch B, Davos CH, Doherty P, et al. The prognostic effect of cardiac rehabilitation in the era of acute revascularisation and statin therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized and non-randomized studies - The Cardiac Rehabilitation Outcome Study (CROS). Eur J Prev Cardiol 2016;23:1914–39. 10.1177/2047487316671181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yohannes AM, Doherty P, Bundy C, et al. The long-term benefits of cardiac rehabilitation on depression, anxiety, physical activity and quality of life. J Clin Nurs 2010;19:2806–13. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lavie CJ, Arena R, Franklin BA. Cardiac rehabilitation and healthy life-style interventions: rectifying program deficiencies to improve patient outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:13–15. 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shields GE, Wells A, Doherty P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of cardiac rehabilitation: a systematic review. Heart 2018;104:1403–10. 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-312809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schuler G, Adams V, Goto Y. Role of exercise in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: results, mechanisms, and new perspectives. Eur Heart J 2013;34:1790–9. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van Halewijn G, Deckers J, Tay HY, et al. Lessons from contemporary trials of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation. International Journal of Cardiology 2017;232:294–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:1 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shah ND, Dunlay SM, Ting HH, et al. Long-term medication adherence after myocardial infarction: experience of a community. Am J Med 2009;122:961.e7–13. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sagar VA, Davies EJ, Briscoe S, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart 2015;2:e000163 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brual J, Gravely S, Suskin N, et al. The role of clinical and geographical factors in the use of hospital versus home-based cardiac rehabilitation. Int J Rehabil 2012;35:220–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krishnamurthi N, Schopfer DW, Ahi T, et al. Predictors of patient participation and completion of home-based cardiac rehabilitation in the veterans health administration for patients with coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol 2019;123:19–24. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.09.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Taylor RS, Dalal H, Jolly K, et al. Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015:CD007130 10.1002/14651858.CD007130.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Anderson L, Sharp GA, Norton RJ, et al. Home-based versus centre-based cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD007130 10.1002/14651858.CD007130.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eder B, Hofmann P, von Duvillard SP, et al. Early 4-week cardiac rehabilitation exercise training in elderly patients after heart surgery. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2010;30:85–92. 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3181be7e32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Macchi C, Fattirolli F, Lova RM, et al. Early and late rehabilitation and physical training in elderly patients after cardiac surgery. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2007;86:826–34. 10.1097/PHM.0b013e318151fd86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aamot IL, Moholdt T, Amundsen BH, et al. Onset of exercise training 14 days after uncomplicated myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010;17:387–92. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e328333edf9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haykowsky M, Scott J, Esch B, et al. A metaanalysis of the effects of exercise training on left ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction: start early andgo longer for greatest exercise benefits on remodeling. Trials 2011;12(92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Davies P, Taylor F, Beswick A, et al. Promoting patient uptake and adherence in cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010;7:Art. No.: CD007131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harrison AS, Doherty P. Does the mode of delivery in Cardiac Rehabilitation determine the extent of psychosocial health outcomes? Int J Cardiol 2018;255:136–9. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.11.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fell J, Dale V, Doherty P. Does the timing of cardiac rehabilitation impact fitness outcomes? An observational analysis. Open Heart 2016;3:e000369 10.1136/openhrt-2015-000369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cossette S, Frasure-Smith N, Dupuis J, et al. Randomized controlled trial of tailored nursing interventions to improve cardiac rehabilitation enrollment. Nurs Res 2012;61:111–20. 10.1097/NNR.0b013e318240dc6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Koene RJ, Prizment AE, Blaes A, et al. Shared risk factors in cardiovascular disease and cancer. Circulation 2016;133:1104–14. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990-2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2224–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kaiser M, Varvel M, Doherty P. Making the case for cardiac rehabilitation: modelling potential impact on readmissions. Leicester: NHS Improvement - Heart, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33. National Audit of Cardiac Rehabilitation. Annual reports 2007 to 2016. York: British Heart Foundation: University of York. [Google Scholar]

- 34. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cardiac rehabilitation services: commissioning guide. London: NICE, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Furze G, Doherty P, Grant-Pearce C. Development of a UK National Certification Programme for Cardiac Rehabilitation (NCP_CR). British Journal of Cardiology 2016;23:102–5. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Doherty P, Salman A, Furze G, et al. Does cardiac rehabilitation meet minimum standards: an observational study using UK national audit? Open Heart 2017;4:e000519 10.1136/openhrt-2016-000519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. NHS England Publications. 2016/2017 National tariff payment system. London: NHS England Publications, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Department of Health. Cardiac rehabilitation: costing tool guidance. London: Department of Health, 2010. [Google Scholar]