Abstract

Aims

Oxidative stress markers and antioxidant enzymes have previously been shown to have prognostic value and associate with adverse outcome in patients with diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 1 (Nrf1) and factor 2 (Nrf2) are among the principal inducers of antioxidant enzyme production. Kelch ECH associating protein 1 (Keap1) is a negative regulator of Nrf2, and BTB (BR-C, ttk and bab) domain and CNC homolog 1 (Bach1) represses the function of both factors. Their significance in DLBCL prognosis is unknown.

Methods

Diagnostic biopsy samples of 76 patients with high-risk DLBCL were retrospectively stained with immunohistochemistry for Nrf1, Nrf2, Keap1 and Bach1, and correlated with clinical data and outcome.

Results

Nuclear Nrf2 and nuclear Bach1 expression were associated with adverse clinical features (anaemia, advanced stage, high IPI, high risk of neutropaenic infections), whereas cytoplasmic Nrf1 and Nrf2 were associated with favourable clinical presentation (normal haemoglobin level, no B symptoms, limited stage). None of the evaluated factors could predict survival alone. However, when two of the following parameters were combined: high nuclear score of Nrf2, low nuclear score of Nrf1, high cytoplasmic score of Nrf1 and low cytoplasmic score of Keap1 were associated with significantly worse overall survival.

Conclusions

Nrf1 and Nrf2 are relevant in disease presentation and overall survival in high-risk DLBCL. Low nuclear expression of Nrf1, high cytoplasmic expression of Nrf1, high nuclear expression of Nrf2 and low cytoplasmic expression of Keap1 are associated with adverse outcome in this patient group.

Keywords: nrf1, nrf2, keap1, bach1, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Introduction

Diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an aggressive malignancy. Oxidative stress markers and several antioxidant enzymes such as thioredoxin-1 (Trx) and peroxiredoxin-6 (Prx6) have been suggested to be associated with clinical disease presentation in DLBCL and to have prognostic value.1 2 Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 1 (Nrf1) and factor 2 (Nrf2) are members of the Cap-N-collar (CNC) family of transcription factors that play vital roles in antioxidant response regulation. Nrf2 especially is considered one of the main inducers of antioxidant enzyme production. It is targeted for degradation by Kelch ECH associating protein 1 (Keap1) in the absence of oxidative stress.3

BTB (BR-C, ttk and bab) domain and CNC homolog 1 (Bach1) are a member of Bach family of transcription factors that repress the function of CNC transcription factors. Both CNC and Bach factors are required to form heterodimers with small musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma (Maf) proteins to bind target DNA.4 Appropriate level of oxidative stress is known to lead to enhanced tumour cell survival and chemoresistance through adaptation and different downstream effects.5 Antioxidant enzymes regulate the level of oxidative stress and its effects in the cell.5 No clinical data exist on the prognostic role of Nrf1, Nrf2, Keap1 and Bach1 in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas.6 In this study the expression and clinical significance of these proteins were evaluated immunohistochemically in high-risk patients with DLBCL.

Materials and methods

This retrospective study included 76 consecutively treated high-risk patients with de novo DLBCL who had diagnostic biopsy samples available for immunohistochemical staining. HIV infection, transformed diseases and primary central nervous system lymphomas were excluded. Patients were treated in 2003–2017 in Oulu University Hospital, Kuopio University Hospital and North Karelia Central Hospital. Patients were eligible for treatment with first-line R-CHOEP regimen (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, etoposide and prednisolone). Risk was retrospectively assessed by the selected treatment (R-CHOEP). High risk here means stages III–IV, and according to WHO 2016 patients with T cell B-cell lymphoma were calculated also as high-risk patients. Extranodal involvement (>1) was also one reason for more intensified treatment schema. Bone marrow infiltration was calculated as increased International Prognoctic Index (IPI). Due to the aggressive therapy most of the patients were younger than 60 years of age. Clinical data were collected from hospital records.

Nrf1, Nrf2, Keap1 and Bach1 were stained immunohistochemically (online supplementary appendix table 1). Samples were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin, and 3 µm sections from the paraffin blocks were cut and placed on SuperFrost Plus glass slides (Menzel-Gläser, Braunschweig, Germany). The slides were incubated at +37°C overnight before deparaffinisation in a clearing agent Histo-Clear (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, Georgia, USA) and rehydration in descending ethanol series. Antigen retrieval was done in the microwave oven (online supplementary appendix table 1). Slides were allowed to cool at room temperature for 20 min and then incubated in a 3% H2O2 solution for 5 min to block the endogenous peroxidase activity. Primary antibody was incubated as outlined in online supplementary appendix table 1. Staining was continued using Dako REAL EnVision Detection System (Dako Denmark A/S, Glostrup, Denmark) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Diaminobenzidine was used to detect the immunoreaction, and nuclei were immunostained with Mayer’s haematoxylin (Reagena, Toivola, Finland). Finally, slides were dehydrated and mounted with Histomount (National Diagnostics). All washes between different steps were performed with phosphate buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20.

jclinpath-2018-205584supp001.pdf (129.4KB, pdf)

The staining was reviewed and analysed on a multihead microscope by two pathologists (K-MH, H-RT) blinded to clinical data. Intensity was assessed as negative, weak or strong with percentage of cells. Modified histoscore was used with the following algorithm: 1 × negative expression +2 × weak expression +3 × strong expression (range 100–300) or 1 × negative expression +4 × positive expression (range 100–400) if expression was recorded either as negative or positive. The latter was applied to cytoplasmic Nrf2 expression and nuclear Bach1 expression due to small differences in expression intensity. Staining was evaluated separately in the cytoplasm and nuclei in each sample. Germinal centre phenotype (GCB) type was determined according to Hans algorithm.7

IBM SPSS Statistics V.23 for Windows was used to perform statistical analysis. Tests included Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, Spearman correlation and Kaplan-Meier log-rank test. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the time of diagnosis to the time of death or to the last follow-up. Appropriate immunohistochemistry (IHC) score cut-off values for survival analysis were chosen from receiver operating characteristic curves. These cut-off values were then combined pairwise to separate different patient groups better. Multivariate analysis with Cox regression was done. The model included IPI and GC phenotype. P values of ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient demographics

Clinical patient characteristics are shown in online supplementary appendix table 2. The median age was 54 years (range 19–69) at the time of diagnosis, and the median follow-up time was 61 months (range 3–165). Eighty-four per cent of patients had stages III–IV disease. Sixty-seven patients (88%) attained full remission, whereas nine patients (12%) had progressive disease with R-CHOEP treatment. During follow-up there were 14 relapses (18%): 11 patients had systemic relapse and 3 patients had central nervous system (CNS) relapse. There were 15 deaths, of which 12 were disease-specific. Of all patients 24 had germinal GCB and 32 had non-GCB type disease7 (online supplementary appendix table 2).

Immunohistochemical analysis and associations between proteins studied

Of the samples, 11% and 21% remained totally negative for cytoplasmic and nuclear Nrf1, respectively. Fifty-six per cent of the samples remained negative for cytoplasmic Nrf2, but nuclear Nrf2 was always positive. Of the samples, 13% and 67% remained negative for cytoplasmic Keap1 and nuclear Bach1, respectively.

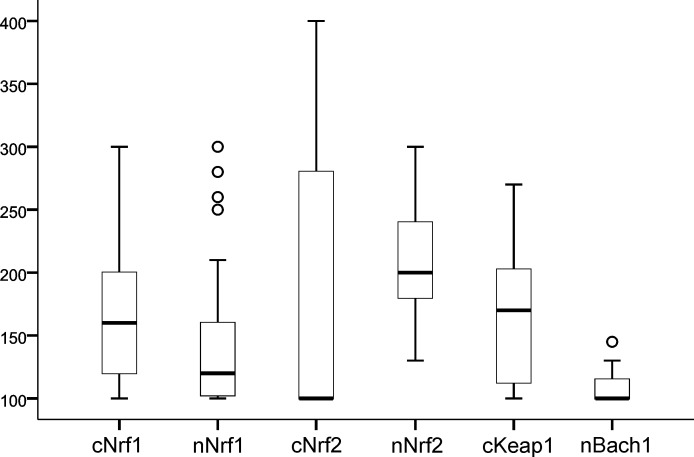

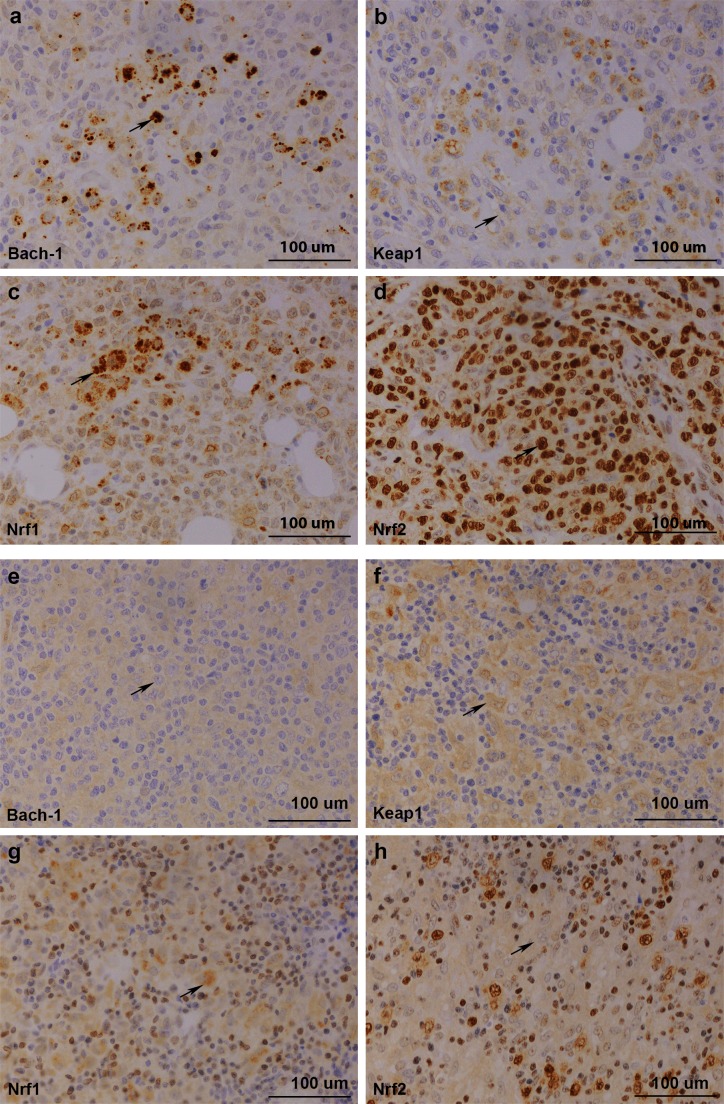

Cytoplasmic expression of Nrf1 correlated with cytoplasmic expression of Keap1 (p=0.021). There was also a positive correlation between nuclear expressions of Nrf1 and Nrf2, but this did not attain statistical significance (p=0.064). There were no other statistically significant correlations between immunohistochemistry. Overall histoscore staining results are presented in figure 1, and two example staining series are presented in figure 2.

Figure 1.

Histoscore results of patients by distribution. Ranges are 100–300 and 100–400 (cNrf2 and nBach1), where 100 means negative staining. Bach1, CNC homolog 1; c, cytoplasmic; Keap1, Kelch ECH associating protein 1; n, nuclear; Nrf1, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 1; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2.

Figure 2.

(A–D) Immunohistochemical staining of patient 1. Biopsy represents non-GC DLBCL from lymph node. From upper left: positive Bach1 expression, low cytoplasmic Keap1 expression, high cytoplasmic Nrf1 expression and high nuclear Nrf1 expression, positive cytoplasmic Nrf2 expression and high nuclear Nrf2 expression. (E–H) Immunohistochemical staining of patient 2. Biopsy represents T cell-rich B-cell lymphoma from lymph node. From upper left: negative Bach1 expression, high cytoplasmic Keap1 expression, high cytoplasmic Nrf1 expression and low nuclear Nrf1 expression, negative cytoplasmic Nrf2 expression and low nuclear Nrf2 expression. GC, germinal centre; Bach1, CNC homolog 1; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; Keap1, Kelch ECH associating protein 1; Nrf1, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 1; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2.

Correlations between immunohistochemical expression and clinical data

IHC scores had some significant associations with disease presentation (online supplementary appendix table 3). Nuclear Nrf2 and nuclear Bach1 expressions were associated with adverse clinical features (anaemia, advanced stage, high IPI) in contrast to cytoplasmic Nrf1 and Nrf2 expressions, which were associated with favourable clinical presentation (normal haemoglobin, no B symptoms, limited stage). Nuclear Nrf1 and Nrf2 expressions were both linked with neutropaenic infection after first treatment cycle. Keap1 did not show any statistically significant associations with disease presentation.

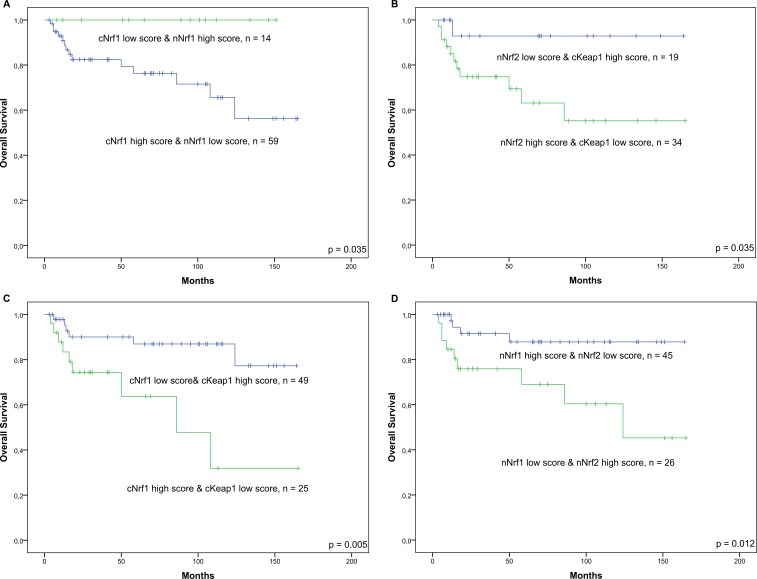

Several factors revealed clear trends for predicting survival, but the differences were not statistically significant. There were statistically significant differences in analysis with combined factors, however, 5-year OS was 100% in patients with low cytoplasmic Nrf1 expression and high nuclear Nrf1 expression compared with 77% in patients with high cytoplasmic Nrf1 expression and low nuclear Nrf1 expression (log-rank p=0.035). The 5-year OS was 93% in patients with low nuclear Nrf2 expression and high cytoplasmic Keap1 expression compared with 63% in patients with high nuclear Nrf2 expression and low cytoplasmic Keap1 expression (log-rank p=0.035). The 5-year OS was 88% in patients with low cytoplasmic Nrf1 expression and high cytoplasmic Keap1 expression compared with 63% in patients with high cytoplasmic Nrf1 expression and low cytoplasmic Keap1 expression (log-rank p=0.005). The 5-year OS was 89% in patients with high nuclear Nrf1 expression and low nuclear Nrf2 expression compared with 67% in patients with low nuclear Nrf1 expression and high nuclear Nrf2 expression (log-rank p=0.012) (figure 3). There was no survival difference according to germinal centre phenotype. When subgroup analyses for survival were stratified between GC and non-GC DLBCL, the prognostic value of other studied markers, apart from nuclear and cytoplasmic Nrf1, remained (figure 3). In Cox regression analysis combined high cytoplasmic Nrf1 and low cytoplasmic Keap1 expression (figure 3) was an independent prognostic factor (HR 3.927; 95% CI 1.116 to 13.821; p=0.033) when comparing with IPI (HR 1.535; 95% CI 0.412 to 5.723; p=0.524) and GC (HR 1.432; 95% 0.411 to 4.984). Combined low nuclear Nrf1 and high nuclear Nrf2 expression (figure 3) was also significant (HR 4.269; 95% CI 1.097 to 16.608; p=0.036) when IPI (HR 1.300; 95% CI 0.334 to 5065; p=0.705) and GC (HR 1.780; 95% CI 0.451 to 7.029; p=0.410) were considered.

Figure 3.

Overall survival charts. Survival according to (A) Nrf1 expression (p=0.035), (B) Nrf2 and Keap1 expression (p=0.035), (C) Nrf1 and Keap1 expression (p=0.005) and (D) Nrf1 and Nrf2 expression (p=0.012). c, cytoplasmic; Keap1, Kelch ECH associating protein 1; n, nuclear; Nrf1, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 1; Nrf2, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2.

Discussion

This is the first study to evaluate prognostic implications of antioxidant enzymes regulators Nrf1, Nrf2, Keap1 or Bach1 in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Besides the higher risk of relapse, patients with these poor prognosis tumours were also more prone to suffer from neutropaenic infections. This is in line with previous studies showing that antioxidant enzymes Prx6 and Trx were associated with worse prognosis in DLBCL.1 2 Moreover, Sewastianik et al 8 have demonstrated in a cell culture model that Trx knockdown sensitises DLBCL cells to doxorubicin, thus demonstrating the causal potential of antioxidant enzymes with chemoresistance. In line with these observations, our results strongly suggest that low nuclear Nrf1 and high nuclear Nrf2 expressions are also associated with adverse outcome in this patient group. In a recent study, Nrf2 and Keap1 expressions were found to be elevated in DLBCL compared with reactive lymph nodes and associate with high IPI and stage.9 Since our study was observing only differences between different lymphoma groups (online supplementary appendix table 2), the sample set did not include benign lymph node specimen. However, our results conform to the reported results by Yi et al 9 as none of the cases in our data set showed negative immunostaining of nuclear Nrf2 and only a few showed negative cytoplasmic Keap1. In contrast, we did not observe any association between Keap1 expression and IPI/stage.

According to the literature, Nrf family members appear to have disease-dependent effects in lymphomas. High Nrf2 mRNA levels have previously been associated with the presence of traditional risk factors of limited stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma,6 while in mantle cell lymphoma Nrf2 pathway activity has been reported to have either favourable10 or adverse effects11 on treatment response. In vitro studies have revealed that inhibition of Nrf2 leads to cytotoxicity in Burkitt lymphoma,12 multiple myeloma,13 and in lymphoblastic12 and myeloid leukaemia cells.14 Apart from the antioxidant properties of Nrf1 and Nrf2, they have both also been related to proteasome-mediated chemoresistance in multiple myeloma.15 16

Based on our findings, high nuclear Nrf2 expression is associated with higher IPI score and adverse outcome in patients with DLBCL. High Nrf2 levels can confer chemoresistance through altered cell cycle effects,17 upregulation of multidrug resistance-associated protein transporters,18 immunosuppression19 and reduced sensitivity to radiotherapy.20 Nrf2 reduces the efficacy of doxorubicin, carboplatin and cisplatin in vitro.20 21 Oncogenes such as Kras, Braf and Myc stimulate the expression of Nrf2.3 In predisposed individuals Nrf2 has also been associated with oncogenesis as seen in a mouse model22 and in some hereditary cancer syndromes.23 Overexpression of Nrf2 is associated with worse survival, which has been recorded in several solid cancers.3 24 25 Supporting these findings strong cytoplasmic expression of Keap1, an inhibitor of Nrf2, was associated with favourable survival in our material. Keap1 is the most important negative regulator of Nrf2 and its deactivation leads to increased levels of Nrf2.3 This phenomenon has been recorded in other malignancies as well.26–29

Nrf1 is found in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane in its inactive state, and it is cleaved from its N-terminal domain on activation. The observed cytoplasmic staining could thus represent its endoplasmic reticulum location and low induction. Our results suggest that Nrf1 may have beneficial effects in the nucleus as it is related to better survival. Prognosis was dismal when Nrf1 had high expression in the cytoplasm even if it was associated with normal haemoglobin and absence of B symptoms. Patients having both high nuclear Nrf2 and low nuclear Nrf1 expression had dismal OS and were independent prognostic factors from IPI and CG phenotype. Nrf1 and Nrf2 compete with each other in binding to electrophile responsive elements and Nrf1 is able to replace Nrf2.30 The combination of high cytoplasmic Nrf1 expression and low cytoplasmic Keap1 expression was also linked to worse OS and was independent from IPI and GC phenotype. Nrf1 binds with Keap1, although the significance of this interaction is unclear.31 Nevertheless, Tian et al 32 recently established Keap1 as a positive regulator of Nrf1. Nrf1 has complex functions in cells, making it challenging to assess its actual biomechanics.31 33 Their net effect in this patient group appears to be survival-promoting, however. Nuclear expressions of Nrf1 and Nrf2 were both associated with febrile neutropaenia after first treatment cycle. The rationale behind this is unknown. Nrf2 has been found to modulate innate immunity and have anti-inflammatory effects. Oxidative stress is also inherently linked with inflammation.34

Bach1 was detected in a minority of samples but was associated with advanced stage disease. It has previously been uniformly related to more aggressive behaviour and chemoresistance in several solid cancers.35–38 There were no survival associations with Bach1, but it is known that all of the transcription factors studied are connected through Mafs and affect the expression and effects of each other.4

After implementation of rituximab into the DLBCL therapy, treatment results have improved dramatically. However, incurable diseases remain and new approaches should be found. Growing evidence points out that targeting antioxidant machinery can taper antioxidant enzyme-mediated chemoresistance in cancer.39–41 Our study adds important new information to this setting. Limitations of this study included its retrospective nature and small sample size. This study represents a selected, young, high-risk patient population as IPI score itself was not statistically significant for treatment outcome. On the other hand, this is a homogeneous series as all patients were treated with R-CHOEP therapy and implies that these mechanisms are important also in this most challenging DLBCL group.

In conclusion, Nrf and Bach protein families appear to have notable relevance in disease presentation and prognosis in high-risk patients with DLBCL, treated with R-CHOEP regimen. This further implies the clinical significance of oxidative stress and antioxidant enzymes in the biology and possibly also in the chemoresistance of DLBCL. This antioxidant and stress response cascade could be a relevant therapeutic target in the future. Results are applicable to most DLBCL as GC, non-GC and T cell-rich types of DLBCL were included in the current study. Relation of these transcription factors to MYC, BCL2 and BCL6 and other DLBCL subtypes should also be determined.

Take home messages.

Nuclear Nrf2 and Bach1 expressions were associated with adverse clinical features in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma.

Low nuclear Nrf1 expression, high cytoplasmic Nrf1 expression, high nuclear Nrf2 expression and low cytoplasmic Keap1 expression are associated with poor overall survival.

Causal roles of these transcription factors should be evaluated in an in vitro model.

Targeting these transcription factors may have therapeutic potential in the future.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Anne Bisi for assistance with immunohistochemical staining.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Mary Frances McMullin.

Contributors: EK designed and wrote the study, analysed the data, and participated in clinical data and biopsy sample collection. H-RT designed the study, assisted with statistical analysis, participated in biopsy sample collection and analysed immunohistochemistry. K-MH took part in biopsy sample collection and analysed immunohistochemistry. MELK, AL, RP and EJ participated in clinical data and biopsy sample collection. PK designed the study and assisted with statistical analysis. YS and TT-H designed the study. OK designed and wrote the study and analysed the data. All authors reviewed and edited manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Finnish Medical Foundation, the Finnish Medical Society Duodecim, the Thelma Mäkikyrö Foundation, Finnish Society for Oncology, Väisänen fund and Terttu Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Northern Ostrobothnia Hospital District Ethics Committee (11/2014), and the study was conducted according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki ethics principles.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Peroja P, Pasanen AK, Haapasaari KM, et al. . Oxidative stress and redox state-regulating enzymes have prognostic relevance in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Exp Hematol Oncol 2012;1 10.1186/2162-3619-1-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kuusisto ME, Haapasaari KM, Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T, et al. . High intensity of cytoplasmic peroxiredoxin VI expression is associated with adverse outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma independently of International Prognostic index. J Clin Pathol 2015;68:552–6. 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ma Q. Role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 2013;53:401–26. 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011112-140320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Katsuoka F, Yamamoto M, proteins Smaf. Small Maf proteins (MAFF, MAFG, MafK): history, structure and function. Gene 2016;586:197–205. 10.1016/j.gene.2016.03.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Landriscina M, Maddalena F, Laudiero G, et al. . Adaptation to oxidative stress, chemoresistance, and cell survival. Antioxid Redox Signal 2009;11:2701–16. 10.1089/ars.2009.2692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karihtala P, Porvari K, Soini Y, et al. . Redox regulating enzymes and connected microRNA regulators have prognostic value in classical Hodgkin lymphomas. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017;2017:1–8. 10.1155/2017/2696071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, et al. . Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood 2004;103:275–82. 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sewastianik T, Szydlowski M, Jablonska E, et al. . FoxO1 is a TXN- and p300-dependent sensor and effector of oxidative stress in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas characterized by increased oxidative metabolism. Oncogene 2016;35:5989–6000. 10.1038/onc.2016.126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yi X, Zhao Y, Xue L, et al. . Expression of Keap1 and Nrf2 in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and its clinical significance. Exp Ther Med 2018;16:573–8. 10.3892/etm.2018.6208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hong DS, Kurzrock R, Supko JG, et al. . A phase I first-in-human trial of bardoxolone methyl in patients with advanced solid tumors and lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18:3396–406. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Weniger MA, Rizzatti EG, Pérez-Galán P, et al. . Treatment-induced oxidative stress and cellular antioxidant capacity determine response to bortezomib in mantle cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:5101–12. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gao DQ, Qian S, Ju T. Anticancer activity of honokiol against lymphoid malignant cells via activation of ROS-JNK and attenuation of Nrf2 and NF-κB. J Buon 2016;21:673–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu HY, Tuckett AZ, Fennell M, et al. . Repurposing of the CDK inhibitor PHA-767491 as a Nrf2 inhibitor drug candidate for cancer therapy via redox modulation. Invest New Drugs 2018;36:590–600. 10.1007/s10637-017-0557-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang J, Su L, Ye Q, et al. . Discovery of a novel Nrf2 inhibitor that induces apoptosis of human acute myeloid leukemia cells. Oncotarget 2017;8:7625–36. 10.18632/oncotarget.13825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li B, Fu J, Chen P, et al. . The nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 and proteasome maturation protein axis mediate bortezomib resistance in multiple myeloma. J Biol Chem 2015;290:29854–68. 10.1074/jbc.M115.664953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tomlin FM, Gerling-Driessen UIM, Liu YC, et al. . Inhibition of NGLY1 inactivates the transcription factor Nrf1 and potentiates proteasome inhibitor cytotoxicity. ACS Cent Sci 2017;3:1143–55. 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ma X, Zhang J, Liu S, et al. . Nrf2 knockdown by shRNA inhibits tumor growth and increases efficacy of chemotherapy in cervical cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2012;69:485–94. 10.1007/s00280-011-1722-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maher JM, Dieter MZ, Aleksunes LM, et al. . Oxidative and electrophilic stress induces multidrug resistance-associated protein transporters via the nuclear factor-E2-related factor-2 transcriptional pathway. Hepatology 2007;46:1597–610. 10.1002/hep.21831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang J, Liu P, Xin S, et al. . Nrf2 suppresses the function of dendritic cells to facilitate the immune escape of glioma cells. Exp Cell Res 2017;360:66–73. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2017.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lister A, Nedjadi T, Kitteringham NR, et al. . Nrf2 is overexpressed in pancreatic cancer: implications for cell proliferation and therapy. Mol Cancer 2011;10 10.1186/1476-4598-10-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wu J, Bao L, Zhang Z, et al. . Nrf2 induces cisplatin resistance via suppressing the iron export related gene SLC40A1 in ovarian cancer cells. Oncotarget 2017;8:93502–15. 10.18632/oncotarget.19548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hamada S, Taguchi K, Masamune A, et al. . Nrf2 promotes mutant K-ras/p53-driven pancreatic carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis 2017;38:661–70. 10.1093/carcin/bgx043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sandhu IS, Maksim NJ, Amouzougan EA, et al. . Sustained NRF2 activation in hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell cancer (HLRCC) and in hereditary tyrosinemia type 1 (HT1). Biochem Soc Trans 2015;43:650–6. 10.1042/BST20150041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kitamura H, Motohashi H. Nrf2 addiction in cancer cells. Cancer Sci 2018;109:900–11. 10.1111/cas.13537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hintsala HR, Haapasaari KM, Soini Y, et al. . An immunohistochemical study of Nfe2l2, Keap1 and 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine and the EMT markers SNAI2, ZEB1 and Twist1 in metastatic melanoma. Histol Histopathol 2017;32:129–36. 10.14670/HH-11-778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Barbano R, Muscarella LA, Pasculli B, et al. . Aberrant Keap1 methylation in breast cancer and association with clinicopathological features. Epigenetics 2013;8:105–12. 10.4161/epi.23319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hanada N, Takahata T, Zhou Q, et al. . Methylation of the keap1 gene promoter region in human colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer 2012;12 10.1186/1471-2407-12-66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Muscarella LA, Barbano R, D'Angelo V, et al. . Regulation of Keap1 expression by promoter methylation in malignant gliomas and association with patient's outcome. Epigenetics 2011;6:317–25. 10.4161/epi.6.3.14408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang R, An J, Ji F, et al. . Hypermethylation of the keap1 gene in human lung cancer cell lines and lung cancer tissues. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2008;373:151–4. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chepelev NL, Zhang H, Liu H, et al. . Competition of nuclear factor-erythroid 2 factors related transcription factor isoforms, Nrf1 and Nrf2, in antioxidant enzyme induction. Redox Biol 2013;1:183–9. 10.1016/j.redox.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Biswas M, Chan JY. Role of Nrf1 in antioxidant response element-mediated gene expression and beyond. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2010;244:16–20. and 10.1016/j.taap.2009.07.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tian W, Rojo de la Vega M, Schmidlin CJ, et al. . Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) differentially regulates nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factors 1 and 2 (NRF1 and NRF2). J Biol Chem 2018;293:2029–40. 10.1074/jbc.RA117.000428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kim HM, Han JW, Chan JY. Nuclear factor Erythroid-2 like 1 (NFE2L1): structure, function and regulation. Gene 2016;584:17–25. and 10.1016/j.gene.2016.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim J, Cha YN, Surh YJ. A protective role of nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor-2 (Nrf2) in inflammatory disorders. Mutat Res 2010;690:12–23. and 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhu G-D, Liu F, OuYang S, et al. . Bach1 promotes the progression of human colorectal cancer through BACH1/CXCR4 pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018;499:120–7. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.02.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Davudian S, Shajari N, Kazemi T, et al. . Bach1 silencing by siRNA inhibits migration of HT-29 colon cancer cells through reduction of metastasis-related genes. Biomed Pharmacother 2016;84:191–8. 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.09.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nie E, Jin X, Wu W, et al. . Bach1 promotes temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma through antagonizing the function of p53. Sci Rep 2016;6 10.1038/srep39743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shajari N, Davudian S, Kazemi T, et al. . Silencing of Bach1 inhibits invasion and migration of prostate cancer cells by altering metastasis-related gene expression. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol 2018;46:1–10. 10.1080/21691401.2017.1374284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Furfaro AL, Traverso N, Domenicotti C, et al. . The Nrf2/HO-1 axis in cancer cell growth and chemoresistance. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016;2016:1–14. 10.1155/2016/1958174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shin D, Kim EH, Lee J, et al. . Nrf2 inhibition reverses resistance to GPX4 inhibitor-induced ferroptosis in head and neck cancer. Free Radic Biol Med 2018;129:454–62. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.10.426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xiang Y, Ye W, Huang C, et al. . Brusatol enhances the chemotherapy efficacy of gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer via the Nrf2 signalling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018;2018:1–10. 10.1155/2018/2360427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jclinpath-2018-205584supp001.pdf (129.4KB, pdf)