Abstract

Background:

Alopecia areata is one of the common causes of nonscarring hair loss with autoimmune etiology. This study was designed to evaluate any added benefit of topical calcipotriol when combined with topical mometasone in the treatment of alopecia areata. To the best of our knowledge, no such study has been conducted in the past.

Materials and Methods:

It was a comparative analytical study done over 100 patients of clinically diagnosed alopecia areata. Group A patients (n = 50) were advised to apply topical mometasone 0.1% cream along with topical calcipotriol 0.005% ointment each once daily, whereas patients of Group B (n = 50) were advised to apply only topical mometasone 0.1% cream in the same amount, once a day. Follow-up of all patients was done at 6, 12, and 24 weeks, and the outcome was assessed according to the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score at every visit.

Results:

Both the groups were statistically comparable in terms of age (P = 0.694) and sex (P = 0.683) distribution. Baseline mean SALT score of Group A and Group B patients was 7.22 and 6.05, respectively (P = 0.145). At the end of 24 weeks, mean SALT score of Group A and Group B patients decreased by 4.24 and 3.39, respectively (P < 0.001). We also found that there was a significant decrease (P < 0.001) in mean SALT score at 24 weeks in patients of both groups when compared with baseline values.

Conclusion:

We found that adding topical calcipotriol 0.005% ointment with topical mometasone 0.1% cream has higher efficacy than topical mometasone alone, in the treatment of alopecia areata.

Key words: Alopecia areata, calcipotriol, Vitamin D analogs

INTRODUCTION

Alopecia areata, also known as pelade or, area celsi, is a condition described by patchy loss of hair without atrophy. Although the etiology of alopecia areata is not known with certainty, the immune system hypothesis seems generally encouraging. Other presumed etiologic components are heredity, emotional stress, and atopy. Diagnosis is mainly clinical. Presence of exclamation mark hair, coudability sign, and “frayed rope appearance” indicate the diagnosis.[1] The severity, course, and prognosis concerning regrowth are highly unpredictable. It has been shown that a lack of Vitamin D receptors reduces epidermal differentiation and hair follicle growth.[2] Moreover, alopecia phenotype has been observed in Vitamin D receptor knockout mice and in patients with hereditary 1,25 (OH)2 D3 resistant rickets.[3] Previous studies have demonstrated a decreased level of 25(OH)D in patients of alopecia areata and an inverse correlation of serum Vitamin D level with disease severity.[4,5] Hence, we envisaged that it would be interesting to study the role of Vitamin D and its analog as a therapeutic option for alopecia areata. This study was designed to evaluate any added benefit of topical calcipotriol when combined with topical mometasone in the treatment of alopecia areata. To the best of our knowledge, no such study has been conducted in the past.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This hospital-based, interventional, comparative analytical study was carried out in the Department of Dermatology at Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College and Hospital, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India. All clinically diagnosed patients of alopecia areata attending the outpatient Department of Dermatology, over a period of 1 year from November 2016 to October 2017, were included in the study. Patients with age <12 years and >65 years, having alopecia areata involving >50% scalp surface area or affecting body sites other than the scalp, patients who were taking or, had taken any topical or systemic steroids, or any immunosuppressive drugs in the past 1 month, and patients with the presence of signs of active infection at the lesional sites were excluded from the study. Ethical clearance from the Institutional Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, A. M. U., Aligarh, was obtained for the same. Patients were explained regarding the nature of study, duration of treatment, and possible side effects of drugs being used in the study, and a proper informed consent was taken. All the patients then went through a set of questionnaire regarding the onset, duration, treatment history, or other comorbidities, and physical examination for evidence of infections at the affected sites was done. All patients were randomly allocated into either of the two groups, Group A and Group B. Randomization was done through “Box and Chit method.” By this method, each and every patient taking part in the study had equal chance of being incorporated into either group.

Mean Vitamin D levels of both the groups were assessed. Group A patients were advised to apply topical mometasone 0.1% cream and topical calcipotriol 0.005% ointment each once daily in morning and evening, respectively (1 fingertip unit for every 2% of body surface area [BSA]), whereas the other set of patients of Group B were advised to apply only topical mometasone 0.1% cream in the same amount, once a day. BSA was calculated using the palm rule (1 palm ~1% BSA). Follow-up of all patients was done at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks, and the outcome was assessed according to the Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) Score[6] at each of these visits. Serial photographs were taken at every visit.

Statistical analysis was carried out using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 19.0, IBM, USA. The Student's t-test was applied to compare the mean values of quantitative variables. Qualitative variables were analyzed with Chi-square test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

There were a total of 100 patients with 50 patients in each group. Both Group A and Group B patients were comparable in terms of age (P = 0.694) and sex distribution (P = 0.683), with males (60%) outnumbering females (40%). The mean age of Group A and Group B patients was 22.38 years and 23.96 years, respectively. At the time of presentation, majority of the patients were having single alopecia patch (44%), disease of 1–3-month duration (38%), and ≤10% scalp area involvement (61%). Focal pattern of the disease was seen in 90% of the patients, whereas sisaipho was seen in just 1% of patient, making it the least common pattern in our study samples. Overall, 31 patients (31%) were having more than one scalp site involved. As far as single site is considered, occipital area was most commonly affected with 27 patients (27%) belonging to this group. Statistically, both Group A and Group B patients were similar for duration of disease (P = 0.349), number of patches (P = 0.325), scalp surface area involvement (P = 0.597), pattern of disease (P = 0.753), and site distribution of disease (P = 0.123). More details regarding the basic clinical characteristics of patients of both the groups are mentioned in Table 1. Mean value of serum Vitamin D was found to be 19.08 ± 7.99 ng/ml in Group A and 19.02 ± 8.25 ng/ml in Group B (P = 0.730). Forty-seven (94%) patients in each group had low Vitamin D levels (<30 ng/ml).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the patients

| Variables | Group A (n=50), n (%) | Group B (n=50), n (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of alopecia areata (months) | |||

| <1 | 10 (20) | 15 (30) | 0.349 |

| >1-3 | 19 (38) | 19 (38) | |

| >3-6 | 5 (10) | 7 (14) | |

| >6 | 16 (32) | 9 (18) | |

| Number of patches | |||

| 1 | 18 (36) | 26 (52) | 0.325 |

| 2 | 14 (28) | 12 (24) | |

| >2 | 18 (36) | 12 (24) | |

| Scalp surface area involved | |||

| <10 | 28 (56) | 33 (66) | 0.597 |

| 11-20 | 18 (36) | 15 (30) | |

| 21-30 | 3 (6) | 2 (4) | |

| 31-40 | 1 (2) | 0 | |

| Pattern of alopecia areata | |||

| Focal | 45 (90) | 45 (90) | 0.753 |

| Reticulate | 3 (6) | 2 (4) | |

| Ophiasis | 2 (4) | 2 (4) | |

| Sisaipho | 0 | 1 (2) | |

| Distribution of scalp sites involved | |||

| Vertex | 4 (8) | 4 (8) | 0.123 |

| Frontal | 8 (16) | 7 (14) | |

| Parietal | 1 (2) | 4 (8) | |

| Temporal | 4 (8) | 10 (20) | |

| Occipital | 12 (24) | 15 (30) | |

| Multiple | 21 (42) | 10 (20) |

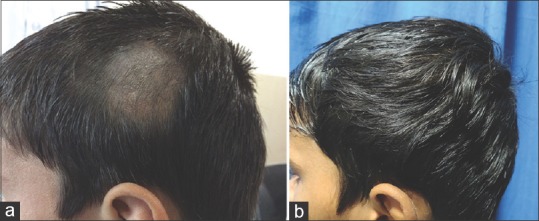

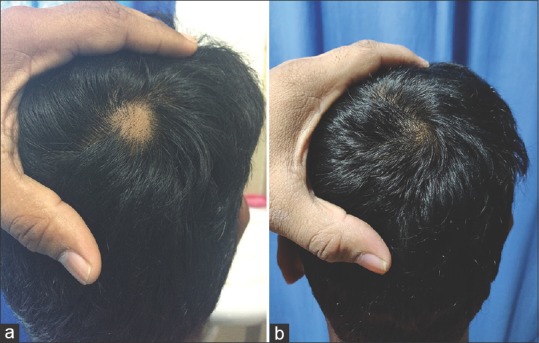

The statistical difference in mean SALT score of both the groups at baseline was nonsignificant (P = 0.145). SALT scores of all the patients were calculated at each visit as a parameter of therapeutic response, and the mean values of SALT score of patients at 6, 12, and 24 weeks of both the groups along with standard deviation are depicted in Table 2. Statistically, we found that there was a significant decrease (P < 0.001) in mean SALT score at 24 weeks in patients of both groups when compared with baseline value of the same group, indicating that the therapy instituted in both the groups was efficacious. Moreover, when decrease of mean SALT score of these two groups was compared together, we found a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) with a higher decrement in Group A patients. [Figures 1a, b and 2a, b].

Table 2.

Mean Severity of Alopecia Tool score and standard deviation at follow-up

| Time of follow-up | SALT score, mean±SD | |

|---|---|---|

| Group A | Group B | |

| Baseline | 7.22±4.27 | 6.05±3.70 |

| 6 weeks | 5.67±4.04 | 4.86±3.79 |

| 12 weeks | 4.30±3.78 | 3.63±3.82 |

| 24 weeks | 2.98±3.35 | 2.66±3.58 |

| P | <0.001 (A) | <0.001 (B) |

SD - Standard deviation; SALT - Severity of Alopecia Tool

Figure 1.

(a) Baseline photograph of a 14-year-old male with alopecia areata on the parietal area of the scalp. (b) Complete resolution of alopecia areata in the patient after treatment with calcipotriol and mometasone

Figure 2.

(a) Baseline photograph of a 20-year-old male with a patch of alopecia areata on the posterior vertex. (b) Resolution of alopecia areata after treatment with mometasone

Minor side effects were observed in a total of 8 patients (4 patients from each group) in our study. In Group A, one patient (1%) developed erythema and one patient (1%) developed dermatitis. Folliculitis was seen in a total of 3 patients (3%); 1 from Group A and 2 from Group B. Atrophy was also seen in a total of 3 patients (3%), with 1 belonging from Group A and 2 from Group B.

DISCUSSION

Alopecia areata is a commonly encountered autoimmune disease in dermatology practice. Of the varied therapeutic approaches, the most fitting one for a particular case has to be chosen depending on the characteristics of disease (acuteness of the disease, extent/severity of involvement, associated systemic diseases present, and recurrence), merits and demerits of the therapy, age of the patient, and, of course, experience of the physician. Although it is comforting to know that, in a large majority of cases, the hair regrows and at the same time it is equally frustrating to note that most therapies only hasten, what ultimately would be a spontaneous remission. Currently, topical and intralesional steroids and contact sensitizers remain the mainstay and popular therapies for alopecia areata.[7,8]

Vitamin D is a prohormone that plays an important role in calcium homeostasis, cell growth, differentiation, and immune regulation. It binds to specific Vitamin D receptor on the nuclei of the target cell to mediate its biological effect.[9] Serum and tissue levels of Vitamin D receptors are found to be decreased in patients of alopecia areata, suggesting a role in the pathogenesis.[10] Vitamin D deficiency is said to be a risk factor for the occurrence of alopecia areata,[11,12] and nutritional supplementation of Vitamin D has been proposed as a treatment modality.[13] Kim et al. reported a case of alopecia areata in a 7-year-old boy with decreased Vitamin D receptor expression, and the topical application of Vitamin D analog calcipotriol resulted in complete recovery in that child.[14] To our knowledge, this is the first research evaluating any added benefit of using topical calcipotriol when combined with topical corticosteroids in the treatment of alopecia areata.

Our study constituted the patients of age ranging from 12 to 60 years. The mean age of Group A and Group B patients was 22.38 and 23.96 years, respectively. Our findings were consistent with those of several other similar studies as done by Narang et al. who found mean age of patients to be 30.4 ± 10.8 years.[15] Unal reported the mean age of patients of alopecia areata in their study as 27.4 ± 9.2 years.[16] Zaher et al. in their study on alopecia areata also found the age of patients ranging from 19 to 48 years, with a mean age of 35.4 ± 8.89 years.[17] Thereby, it can be reported that alopecia areata is mostly a disease of young people.

In this study, most of the patients (38%) reported to the hospital with a disease duration of 1–3 months. Previous studies have shown a wide diversity in the duration of alopecia areata at the time of presentation among their patients. In a study done by Narang et al., they found a mean duration of 42 weeks,[15] whereas in a similar study by Unal, it was found to be 5.8 ± 3.2 months.[16] Zaher et al. in their study showed that the disease duration ranged between 6 and 9 months (mean 7.7 ± 2.89).[17] This early reporting may be due to the social stigma associated with the disease and the location of our tertiary health-care center in a small town, making it easily accessible for the patients.

Majority of the patients in our study presented with a single patch (44%) of alopecia areata. In a similar study by Narang et al., they also found single patch presentation in 70% of their patients.[15] Moreover, 61% of patients had involvement of ≤10% scalp surface area, whereas only 6 patients (6%) presented with more than 20% involvement of scalp surface area. The higher proportion of patients presenting with less scalp area involvement and single patch may be because of easy and affordable accessibility of tertiary health center as well as the cosmetic deformity arising out of the disease.

The most common clinical pattern seen in our study was focal (90%), followed by reticulate pattern (5%). The pattern least commonly observed was sisaipho, seen in only 1 patient (1%), out of all the 100 patients. This finding is consistent with other studies like the one done by Pratt et al. who also found focal alopecia areata as the most common variant.[18]

We observed that 31% of patients had involvement of ≥1 area over the scalp. However, on isolated basis, occipital area was most commonly affected (27%), followed by frontal area (15%). The high incidence of involvement of occipital area may be attributed to the high likelihood of visualization of bald patch because of the usual presence of small hair at the occipital site.

We found that 94% of patients had low Vitamin D levels (<30 ng/ml). Our observations are consistent with the findings of Narang et al. who also found Vitamin D deficiency in 91% of Indian patients with alopecia areata.[15]

In our study, baseline SALT scores were highly variable among the patients, ranging from 0.9 to 24. Mean baseline SALT score of Group A and Group B patients was found to be 7.22 and 6.05, respectively. SALT scoring system is the standard method of measuring the severity of alopecia areata. Narang et al. in their study on alopecia areata found the mean baseline SALT score as 14.6.[15] Similarly, Zaher et al. found a mean baseline SALT score of 7.6 in a study on thirty patients of alopecia areata.[17]

Over a period of 24 weeks, mean SALT score in Group A and Group B patients decreased by 4.24 and 3.39, respectively. Çerman et al. in their study of topical calcipotriol therapy for mild-to-moderate alopecia areata found a significant decrease (P = 0.001) in mean SALT score at 12 weeks of follow-up.[19] Similar results were also reported by Zaher et al. in their study on treatment of patients with alopecia areata with topical mometasone, in which they found a decrease of 2.30 in mean SALT score over a period of 12 weeks.[17] Unal in his study on treatment of alopecia areata with topical mometasone found similar results.[16] When the decrease in mean SALT score of both Groups A and B was compared statistically, the difference came out to be statistically significant (P < 0.001), with a higher decrease in SALT score seen in Group A, i.e., the patients also applied calcipotriol in addition to mometasone. Therefore, topical calcipotriol seems to provide additional efficacy, when combined with topical mometasone in the treatment of alopecia areata.

No life-threatening major side effect was seen in any of the patients of either group, thereby making topical calcipotriol along with topical mometasone a safe therapy in addition to being efficacious.

This was an unblinded analytical study with both participants and investigators being aware of the nature of treatment. However, double-blinded studies with larger sample sizes need to be carried out to further validate these results.

CONCLUSION

We found that adding topical calcipotriol 0.005% ointment with topical mometasone 0.1% cream has higher efficacy than topical mometasone alone, in the treatment of alopecia areata. As topical steroid is known to cause atrophy at the site of application, adding topical calcipotriol may decrease the total cumulative dose of steroid needed because of the increased efficacy of combination therapy.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wadhwa SL, Khopkar U, Nischal KC. Hair and scalp disorders. In: Valia RG, Valia AR, editors. IADVL Textbook of Dermatology. 3rd ed. New Delhi (India): Bhalani Publishers; 2015. p. 903. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xie Z, Komuves L, Yu QC, Elalieh H, Ng DC, Leary C, et al. Lack of the Vitamin D receptor is associated with reduced epidermal differentiation and hair follicle growth. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:11–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li YC, Pirro AE, Amling M, Delling G, Baron R, Bronson R, et al. Targeted ablation of the Vitamin D receptor: An animal model of Vitamin D-dependent rickets type II with alopecia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9831–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhat YJ, Latif I, Malik R, Hassan I, Sheikh G, Lone KS, et al. Vitamin D level in alopecia areata. Indian J Dermatol. 2017;62:407–10. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_677_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aksu Cerman A, Sarikaya Solak S, Kivanc Altunay I. Vitamin D deficiency in alopecia areata. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170:1299–304. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhor U, Pande S. Scoring systems in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006;72:315–21. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.26722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell AJ, Balle MR. Alopecia areata. Dermatol Clin. 1987;5:553–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Messenger AG, McKillop J, Farrant P, McDonagh AJ, Sladden M. British Association of Dermatologists' guidelines for the management of alopecia areata 2012. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:916–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skorija K, Cox M, Sisk JM, Dowd DR, MacDonald PN, Thompson CC, et al. Ligand-independent actions of the Vitamin D receptor maintain hair follicle homeostasis. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:855–62. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fawzi MM, Mahmoud SB, Ahmed SF, Shaker OG. Assessment of Vitamin D receptors in alopecia areata and androgenetic alopecia. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2016;15:318–23. doi: 10.1111/jocd.12224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahamid M, Abu-Elhija O, Samamra M, Mahamid A, Nseir W. Association between Vitamin D levels and alopecia areata. Isr Med Assoc J. 2014;16:367–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gade VK, Mony A, Munisamy M, Chandrashekar L, Rajappa M. An investigation of Vitamin D status in alopecia areata. Clin Exp Med. 2018;18:577–84. doi: 10.1007/s10238-018-0511-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S, Kim BJ, Lee CH, Lee WS. Increased prevalence of Vitamin D deficiency in patients with alopecia areata: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:1214–21. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DH, Lee JW, Kim IS, Choi SY, Lim YY, Kim HM, et al. Successful treatment of alopecia areata with topical calcipotriol. Ann Dermatol. 2012;24:341–4. doi: 10.5021/ad.2012.24.3.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Narang T, Daroach M, Kumaran MS. Efficacy and safety of topical calcipotriol in management of alopecia areata: A pilot study. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30:e12464. doi: 10.1111/dth.12464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unal M. Use of adapalene in alopecia areata: Efficacy and safety of mometasone furoate 0.1% cream versus combination of mometasone furoate 0.1% cream and adapalene 0.1% gel in alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:e12574. doi: 10.1111/dth.12574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaher H, Gawdat HI, Hegazy RA, Hassan M. Bimatoprost versus mometasone furoate in the treatment of scalp alopecia areata: A pilot study. Dermatology. 2015;230:308–13. doi: 10.1159/000371416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pratt CH, King LE, Jr, Messenger AG, Christiano AM, Sundberg JP. Alopecia areata. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17011. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Çerman AA, Solak SS, Altunay İ, Küçükünal NA. Topical calcipotriol therapy for mild-to-moderate alopecia areata: A retrospective study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:616–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]