Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of high-dose taurine supplementation for prevention of stroke-like episodes of MELAS (mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes), a rare genetic disorder caused by point mutations in the mitochondrial DNA that lead to a taurine modification defect at the first anticodon nucleotide of mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR), resulting in failure to decode codons accurately.

Methods

After the nationwide survey of MELAS, we conducted a multicentre, open-label, phase III trial in which 10 patients with recurrent stroke-like episodes received high-dose taurine (9 g or 12 g per day) for 52 weeks. The primary endpoint was the complete prevention of stroke-like episodes during the evaluation period. The taurine modification rate of mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) was measured before and after the trial.

Results

The proportion of patients who reached the primary endpoint (100% responder rate) was 60% (95% CI 26.2% to 87.8%). The 50% responder rate, that is, the number of patients achieving a 50% or greater reduction in frequency of stroke-like episodes, was 80% (95% CI 44.4% to 97.5%). Taurine reduced the annual relapse rate of stroke-like episodes from 2.22 to 0.72 (P=0.001). Five patients showed a significant increase in the taurine modification of mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) from peripheral blood leukocytes (P<0.05). No severe adverse events were associated with taurine.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrates that oral taurine supplementation can effectively reduce the recurrence of stroke-like episodes and increase taurine modification in mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) in MELAS.

Trial registration number

UMIN000011908.

Introduction

Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) is a major clinical entity encompassing mitochondrial diseases resulting from mitochondrial dysfunction.1–3 Stroke-like episodes, the most critical symptom of MELAS, are characterised by an abrupt onset of cortical neurological deficits with typical MRI abnormalities not conforming to the distribution of main arteries.4 5 MELAS progresses over years with accumulation of neurological deficits resulting from recurrent stroke-like episodes, which dictate the prognosis of MELAS: 20.8% patients die within a median time of 7.3 years after diagnosis.6 From the onset of neurological deficits, the overall median survival time of patients with MELAS was estimated as 16.9 years.7

Among more than 50 causative mutations reported in the mitochondrial DNA,8 9 3243A>G and 3271T>C mutations in the mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) gene (MT-TL1) occur in 80%2 10 and 10%11 of patients with MELAS, respectively. The precise molecular mechanisms by which these point mutations lead to various clinical manifestations of MELAS remain to be elucidated.

In 1966, Francis Crick predicted certain chemical modifications at the first anticodon nucleotide of tRNAs because it interacts with the corresponding third codon nucleotide in mRNA through non-canonical Watson-Crick geometry, termed ‘wobble pairing’.12 Yasukawa et al found that taurine, a sulfur-containing β-amino acid, modifies the first anticodon nucleotide in normal human mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR).13 Surprisingly, the taurine modification was absent in mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) of cells derived from patients with MELAS harbouring the 3243A>G or 3271T>C mutation.14 15 Because the defect in taurine modification in mutant mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) causes a failure in deciphering the cognate codon,15 these findings raised an intriguing possibility that MELAS results from mitochondrial dysfunction due to defective mitochondrial gene translation. More recently, knockout of the taurine modification enzyme proved impairment of mitochondrial translation and respiratory activity.16

From the first-ever proposal by Yasukawa et al 13, a novel disease concept termed tRNA modification disorders, encompassing over 18 diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, type 2 diabetes and several genetic disorders, has recently emerged.17 To date, no therapeutic intervention has yet succeeded in alleviating impaired tRNA modifications observed in these disorders.17 We postulated that high-dose taurine supplementation would restore the taurine modification defect in mutant mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) and ameliorate mitochondrial dysfunction and clinical manifestations in patients with MELAS. Indeed, we previously showed that addition of taurine to the culture media at the final concentration of 0.3 mM alleviated the decreases in VO2 and mitochondrial membrane potential in patient-derived pathogenic cells harbouring the 3243A>G mutation.18 In a preliminary study, high-dose oral administration of 12 g taurine elevated the plasma concentration above 0.3 mM and completely prevented stroke-like episodes in two patients with MELAS for more than 9 years.18

Following a nationwide survey of MELAS across Japan, we conducted a multicentre, open-label, phase III trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of high-dose taurine supplementation for prevention of stroke-like episodes. We further investigated the molecular effect of taurine supplementation by determining taurine modification in mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) from peripheral blood leucocytes of participants in the trial.

Methods

Nationwide survey

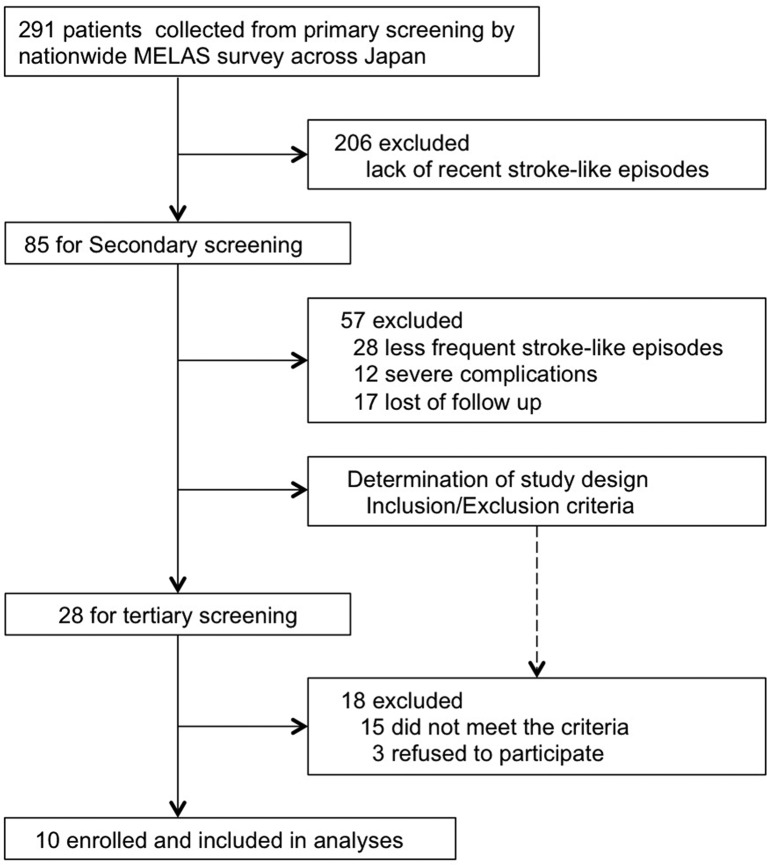

To enrol participants in this clinical trial, we performed a nationwide survey of patients with MELAS across Japan (figure 1, online supplementary figure S1–4). We conducted a primary screening by sending questionnaires to determine the number of patients with MELAS in 911 clinical departments. The design of the trial protocol and enrolment of participants were based on the information obtained with the secondary and tertiary screenings.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the recruitment based on the data collected from nationwide survey.

jnnp-2018-317964supp001.pdf (8.1MB, pdf)

Trial participants

Eligible patients were those diagnosed with MELAS according to the Japanese diagnostic criteria for MELAS,6 which were based on the previous criteria by Hirano et al 19 and Hirano and Pavlakis,20 in agreement with the MELAS study committee in Japan.

Candidates were screened by genetic testing to identify patients harbouring 3243A>G, 3271T>G, 3244G>A, 3258T>C or 3291T>C mutations proven to cause the taurine modification defect in mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR).21 Additional eligibility criteria included prior continuous administration of other therapies,22 such as coenzyme Q10,23 antiepileptics and nitric oxide donors including L-arginine.24 Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in UMIN clinical trial database (http://www.umin.ac.jp; UMIN000011908).

Trial design

The dose of orally administered taurine was determined based on the participant’s body weight categories, 12 g for 40 kg or more, 9 g for 25–39 kg, 6 g for 15–24 kg and 3 g for less than 15 kg, so as to reach the effective plasma concentration of taurine, 0.3 mM, which improves mitochondrial dysfunction in our previous study.18

We defined stroke-like episodes of MELAS in the inclusion criteria as focal neurological deficits with abrupt onset, including (1) hemiparesis or monoparesis, (2) cortical sensory deficit (extinction), (3) cortical visual deficit, (4) aphasia, (5) apraxia and (6) agnosia. At the time of registration, brain MRI was not mandatory in order to avoid underestimation of the frequency of stroke-like episodes during the pretrial period. Based on the data from the nationwide survey, we selected participants who had frequent recurrence of stroke-like episodes; more than twice within the last 78 weeks and at least once within the last 52 weeks before the date of enrolment.

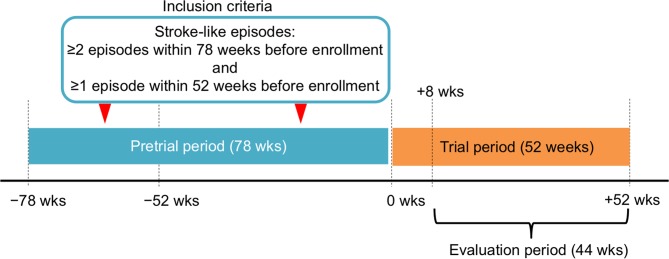

Taurine was administered for 52 weeks of the trial period and the first 8 weeks after the taurine administration were not included in the evaluation period (figure 2). Stroke-like episodes observed during the evaluation period were precisely defined as abrupt-onset focal neurological deficits confirmed by brain MRI abnormalities.

Figure 2.

Trial design.

Taisho Pharmaceutical (Tokyo, Japan) provided good manufacturing practice-grade taurine. This trial was conducted in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice guidelines25 and approved by Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency on 13 September 2013. Each institutional review board (IRB) of individual 10 clinical institutions participating in this trial approved all trial procedures, and all patients provided written informed consent before the start of the trial. After participants’ registration, this trial was stated from 3 October 2013.

Efficacy and safety assessment

The primary endpoint was the 100% responder rate, defined as the percentage of patients with no stroke-like episodes during the trial period. The secondary endpoints included the following: (1) the 50% responder rate defined as the percentage of patients achieving 50% or greater reduction in frequency of stroke-like episodes during the trial period; (2) the number of attacks with focal neurological deficits with or without brain MRI abnormalities; (3) the levels of lactate, pyruvate and taurine in blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF); (4) the number of times high-intensity lesions were confirmed with brain MRI in patients suffering from headache, nausea, vomiting, seizure or impaired consciousness; (5) the frequency of intravenous treatment with L-arginine24 before or after taurine administration, and (6) the disease severity index in accordance with the Japanese Mitochondrial Disease Rating Scale,6 which was modified from the European Neuromuscular Conference mitochondrial disease scale.26

Safety was assessed by analysing adverse events between the date of enrolment and the end of the trial. Assessment included any changes in physical examination, Mini Mental State Examination, laboratory tests and echocardiography. Patients and guardians were informed on precautionary measures and warning signs.

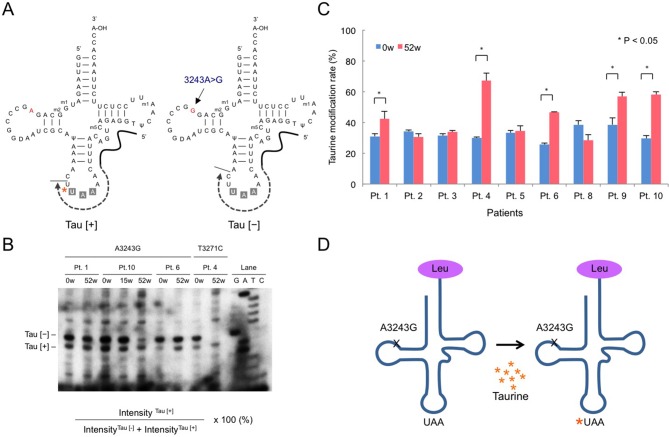

Analysis of taurine modification of mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR)

As a first-in-human analysis, we measured the rate of taurine modification of mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) in peripheral blood leucocytes using the primer extension method.21 Briefly, the specific reverse primer, ACCTCTGACTGTAAAG, which corresponds to the 3′-adjacent site of the anticodon in mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) was 5′-labelled with [γ-32P]ATP using T4 polynucleokinase (T4 PNK; NEB, Boston, Massachusetts, USA). Total RNA isolated from peripheral blood leucocytes was reverse-transcribed with the labelled primer using a Moloney mouse leukaemia virus (M-MuLV) reverse transcriptase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) with dATP, dTTP and ddGTP. The reaction mixture was electrophoresed in a 15% polyacrylamide gel containing 7 M urea. The 20 bp and 21 bp bands corresponding to the labelled partial cDNA products with (Tau (+)) or without (Tau (−)) taurine modification of the first anticodons, respectively, were visualised. The taurine modification rate (%) was calculated based on the densitometric intensities of the 20 bp and 21 bp bands using the following formula: intensityTau (+)/(intensityTau (+)+intensityTau (−))×100. Details are described in the online supplementary file.

Statistical analysis

The 100% and 50% responder rates and 95% Pearson-Clopper CIs were estimated. For other endpoints, one-sample t-test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to compare pre-treatment and post-treatment values. Two-sided P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant for all analyses. For this trial, the intent-to-treat population was defined as all subjects enrolled in the trial who received at least one dose of taurine; all patients were analysed for primary and secondary endpoints. A sample size of 10 subjects was required to test the null hypothesis that the true 100% responder rate was ≤5% with the alternative hypothesis that the true 100% responder rate was ≥50%, with more than 90% power and an alpha level of 0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (V.9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Participant disposition

A total of 291 patients with MELAS were identified by the nationwide MELAS survey from January to May 2013 (figure 1, online supplementary figure S1, 2) from 911 clinical departments across Japan. Since the population of Japan was approximately 126 million in 2013, the prevalence of MELAS was estimated as at least 0.22 per 100 000 population. Eighty-five patients (29.2%) had more than two stroke-like episodes within the last 2 years. Secondary screening (online supplementary figure S3) identified 28 patients having frequent stroke-like episodes without severe clinical complications.

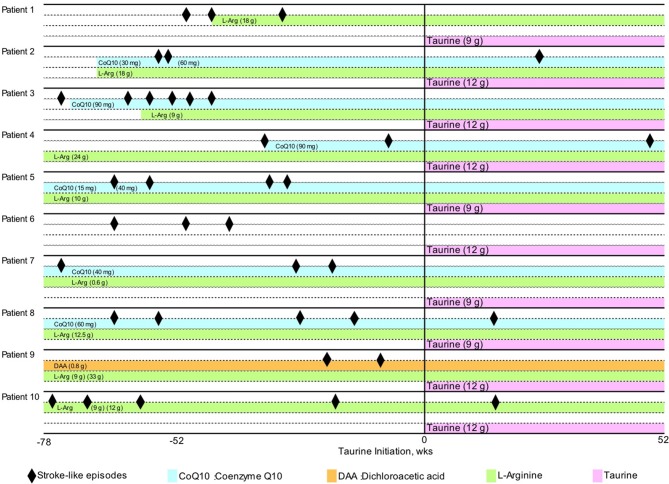

Based on the tertiary screening (online supplementary figure S4), 10 patients from 10 departments who met the inclusion criteria were enrolled in the study (figures 1 and 2). Baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in table 1. The mean age of participants was 29.1 years (range, 14–46 years). The patients received 9 g or 12 g taurine per day for 52 weeks. Nine patients harboured the 3243A>G mutation and one had the 3271T>C mutation in the mitochondrial DNA. The degree of heteroplasmy, that is, the percentage of mutant mitochondrial DNA, ranged from 21.5% to 65.8% in peripheral blood leucocytes. The number of stroke-like episodes within the 78 weeks before trial enrolment ranged between 2 and 6, regardless of prior continuous administration of other drugs, including CoQ10, L-arginine and dichloroacetic acid (figure 3). Among a total of 33 stroke-like episodes experienced by patients before taurine supplementation, brain MRI examination was performed in only 20 episodes (online supplementary table S1).

Table 1.

Demographics of the patients and frequency of stroke-like episodes

| Patient number | Age | Gender | Taurine dose (g/day) |

Mitochondrial DNA mutation | Heteroplasmy in peripheral blood leucocytes (%) |

Pretrial period frequency of stroke-like episodes per year* | Evaluation period† frequency of stroke-like episodes per year | Percentage reduction of stroke-like episodes by taurine treatment |

| 1 | 46 | F | 9 | 3243A>G | 28.7 | 2.26 | 0 | 100 |

| 2 | 45 | M | 12 | 3243A>G | 29.5 | 1.56 | 1.20 | 32.8 |

| 3 | 30 | F | 12 | 3243A>G | 43.4 | 3.67 | 0 | 100 |

| 4 | 19 | M | 12 | 3243A>G | 53 | 1.34 | 1.17 | 12.5 |

| 5 | 15 | M | 9 | 3243A>G | 65.8 | 2.67 | 0 | 100 |

| 6 | 31 | M | 12 | 3271T>C | 30.9 | 2.01 | 0 | 100 |

| 7 | 30 | F | 9 | 3243A>G | NT†† | 2.01 | 0 | 100 |

| 8 | 14 | M | 9 | 3243A>G | 57.8 | 2.67 | 1.21 | 54.7 |

| 9 | 38 | M | 12 | 3243A>G | 21.5 | 1.34 | 0 | 100 |

| 10 | 23 | M | 12 | 3243A>G | 39.4 | 2.67 | 1.25 | 53.4 |

*Stroke-like episodes in the pretrial period were not necessarily confirmed by MRI.

†The first 8 weeks after the start of the study drug administration were not included in the evaluation period.

†† not tested.

Figure 3.

Clinical course. Stroke-like episodes (black diamonds) and continuous administered drugs are shown. CoQ10, coenzyme Q10; DAA, dichloroacetate; L-Arg, L-arginine.

Efficacy

All 10 patients experienced a decrease in frequency of stroke-like episodes with taurine supplementation therapy (table 1, figure 3). Six patients had no stroke-like episodes confirmed by the absence of MRI abnormalities during the evaluation period (patients 1, 3, 5, 6, 7 and 9; table 1, figure 3). Thus, the primary outcome of the trial, the 100% responder rate was 60.0% (95% CI 26.2% to 87.8%), and the lower limit of 95% CI was higher than the 100% responder rate of 5% under the null hypothesis.

During the 52 weeks of trial period, the frequency of stroke-like episodes was decreased more than 50% in eight patients treated with taurine (patients 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10; table 1, figure 3) compared with those not treated with taurine; thus, the 50% responder rate was 80% (95% CI 44.4% to 97.5%). Additionally, the number of focal neurological deficits significantly decreased from 33 during the pretrial period to 8 during the evaluation period (online supplementary table S1, 2). Thus, oral taurine supplementation significantly reduced the annual relapse rate of focal neurological deficits from 2.22±0.73 to 0.72±0.62 (P=0.001, table 2). A single patient (patient 5) experienced a non-focal neurological deficit, headache and nausea, concomitantly with a high-intensity lesion in the brain MRI.

Table 2.

Efficacy endpoints

| N | Pretrial period | Evaluation period† | P value | Statistical analysis | |

| Annual relapse rate of focal neurological deficits | 10 | 2.22±0.73 | 0.72±0.62 | 0.001* | t-test |

| Frequency of intravenous formulation with L-arginine | 10 | 6.94±10.54 | 1.09±2.39 | 0.1405 | t-test |

| JMDRS | Wilcoxon signed-rank test | ||||

| Section 1 | 10 | 5.5 (1–11) | 6 (1–12) | 0.7969 | |

| Section 2 | 10 | 3.5 (0–13) | 4.5 (0–13) | 0.8125 | |

| Section 3 | 10 | 3 (0–4) | 3 (0–7) | 0.5 | |

| Section 4 | 10 | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–2) | 1 | |

| Section 5 | 10 | 0.5 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 1 | |

| Section 6 | 10 | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 1 | |

| Section 7 | 10 | 1.5 (0–5) | 2.5 (0–6) | 0.375 | |

| Total scores | 10 | 15 (2–28) | 18 (1–32) | 0.5625 | |

| Taurine | t-test | ||||

| Plasma taurine (nmol/mL) | 10 | 57.57±20.29 | 945.67±406.18 | 0.0001* | |

| CSF taurine (nmol/mL) | 7 | 11.24±2.88 | 42.11±13.77 | 0.0007* | |

| Lactate and pyruvate | t-test | ||||

| Serum lactate (mg/dL) | 10 | 32.49±12.97 | 35.76±12.64 | 0.4079 | |

| CSF lactate (mg/dL) | 7 | 40.54±15.31 | 45.73±17.87 | 0.4742 | |

| Serum pyruvate (mg/dL) | 10 | 1.26±0.39 | 1.42±0.51 | 0.395 | |

| CSF pyruvate (mg/dL) | 7 | 1.39±0.39 | 1.72±0.52 | 0.1672 | |

| Serum lactate:pyruvate ratio | 10 | 26.14±5.92 | 25.51±4.89 | 0.7048 | |

| CSF lactate:pyruvate ratio | 7 | 28.47±4.93 | 26.03±4.68 | 0.0521 |

Data are expressed as mean±SD, except JMDRS being expressed as median (range).

*P<0.05.

†The first 8 weeks after the start of the study drug administration were not included in the evaluation period.

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; JMDRS, Japanese Mitochondrial Disease Rating Scale.

Taurine supplementation therapy significantly increased the levels of taurine in blood (945.67±406.18 vs 57.57±20.29 nmol/mL, P=0.0001) and CSF (42.11±13.77 vs 11.24±2.88 nmol/mL, P=0.0007; table 2). No significant changes were observed in other efficacy endpoints except taurine concentrations in the blood and CSF (table 2).

We evaluated the rate of taurine modification in mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) from peripheral blood leucocytes in nine patients as a first-in-human analysis (figure 4). The rate of taurine modification of mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) was significantly increased in five patients (P<0.05).

Figure 4.

Taurine modification rate of mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) from peripheral blood leucocytes. (A) Schematic representation of the primer extension method. Total RNA isolated from peripheral blood leucocytes was reverse-transcribed using the specific reverse primer. Taurine modification of the first anticodon nucleotide, uridine (U), is shown by an asterisk. (B) Representative polyacrylamide gel. Upper: the labelled partial cDNA products with or without the taurine modification were indicated by Tau (+) or Tau (−). Lanes G, A, C, T and ladder represent the primer extension reactions performed in the presence of ddGTP, ddATP, ddCTP, ddTTP and dNTP mix, respectively. Lower: taurine modification rates calculated based on the radiointensities of Tau (+) or Tau (−). (C) Changes in the taurine modification rate between pretrial (0 w) and at the end of the trial period (52 w). Student’s t-test; *P<0.05. (D) Schematic representation of the effect of high-dose taurine supplementation on taurine modification defects in mutant mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR).

Safety

None of the patients discontinued treatment with taurine supplementation, although 84 adverse events occurred in all 10 patients over 52 weeks of treatment (table 3). Six patients experienced adverse events associated with taurine supplementation. Two severe adverse events were reported in two patients: serum creatine kinase elevation and acute gastroenteritis. However, these were not considered to be due to taurine supplementation.

Table 3.

Adverse events observed in patients during the trial period

| Event | Number of patients | Number of events |

| Total adverse events | 10 | 84 |

| Treatment-unrelated adverse events | 10 | 74 |

| Serious adverse event | 2 | 2 |

| HyperCKemia* | 1 | 1 |

| Gastritis | 1 | 1 |

| Mild to moderate adverse events | 10 | 72 |

| Common (occurred more than two patients) | ||

| Nasopharyngitis | 5 | 7 |

| Diarrhoea | 3 | 4 |

| Otalgia | 2 | 3 |

| Granulocytosis | 2 | 3 |

| Fever | 2 | 2 |

| Vomiting | 2 | 2 |

| Influenza | 2 | 2 |

| Crush | 2 | 2 |

| Leucocytosis | 2 | 2 |

| HyperCKemia | 2 | 2 |

| C-reactive protein elevation | 2 | 2 |

| Treatment-related adverse events | 6 | 10 |

| Serious adverse event | 0 | 0 |

| Mild to moderate adverse events | 6 | 10 |

| Diarrhoea | 1 | 1 |

| Constipation | 1 | 1 |

| Appetite loss | 1 | 1 |

| Insomnia | 1 | 1 |

| Oral aphtha | 1 | 1 |

| Reflux oesophagitis | 1 | 1 |

| γ-GTP elevation | 1 | 1 |

| Pollalkisuria | 1 | 1 |

| Hiatal hernia | 1 | 1 |

| Gastroenteritis | 1 | 1 |

*CK, creatine kinase.

Discussion

The present clinical trial demonstrated that oral supplementation with high-dose taurine was effective in preventing stroke-like episodes, as evidenced by the high 100% responder rate of 60% (95% CI 26.2% to 87.8%). The lower limit of 95% CI was higher than the true 100% responder rate of 5% under the null hypothesis. Furthermore, the 50% responder rate reached 80%, and the annual relapse rate of stroke-like episodes significantly decreased with concomitant increases in blood and CSF taurine levels. Adverse events associated with taurine were observed among the participants, but no serious adverse events associated with taurine supplementation were reported.

Growing evidence suggest that dysfunction in post-transcriptional tRNA modifications can lead to various pathological conditions, termed as tRNA modification disorders.17 Critically, the loss of modification in the first anticodon nucleotide of mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) in MELAS was expected to directly inhibit its pairing to the cognate third codon nucleotide in mRNA as predicted by Crick.12 In this study, we showed that the high-dose taurine supplementation was able to ameliorate taurine modification defect in mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) in peripheral blood leucocytes in vivo, which supported a therapeutic rationale of the taurine supplementation. High-dose taurine could improve the taurine modification of the mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR) by the first anticodon modification enzyme, mitochondrial translation optimisation 1 (MTO1).16 In addition, taurine could alleviate impaired energy metabolism through increase of ATP production in the pathogenesis leading to MELAS.27

Several clinical trials have been conducted for the treatment of MELAS22; however, thus far, no therapeutic rationale based on molecular mechanisms of this disease has been provided. Taurine is a physiological amino acid that accounts for 0.1% of the human body weight.28 It is derived mostly from food and, to a lesser extent, endogenously synthesised from cysteine and methionine. Thus, establishing a safe taurine supplementation therapy is a significant progress in the treatment of this devastating, rare genetic disorder.

Limitations of this study include the lack of a double-blind, placebo-control group of taurine supplementation due to the small number of participants fulfilling the inclusion criteria. The nationwide survey estimated the Japanese prevalence of MELAS as at least 0.22 per 100 000 population, which is consistent with the previous Japanese study.6 In addition, short life expectancy and poor prognosis described in natural history studies6 7 29 practically confined the number of participants as well as ethically allowed the continuation of other therapies prior to taurine supplementation. Indeed, 9 of 10 participants were priorly administered L-arginine, which was reported to decrease the frequency of stroke-like episodes in a clinical study.24 However, even in these patients, the frequency of stroke-like episodes was remarkably decreased with taurine supplementation. Further clinical studies are required to determine the synergy effect of taurine and L-arginine for prevention of stroke-like episodes in MELAS.

In conclusion, in this open-label, phase III trial, oral high-dose taurine supplementation was effective and safe for the prevention of stroke-like episodes in patients with MELAS by ameliorating the modification defect in the first anticodon nucleotide of mitochondrial tRNALeu(UUR).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to K Tanda, F Uemura, M Ogawa, Y Shimada, T Ohtsuki, T Irinaga, K Sakai and M Tsuboi (Department of Neurology, Kawasaki Medical School) for their technical assistance.

Footnotes

Contributors: YO, HH, AH, YK, YG and YS conceptualised and designed the study, recruited patients, contributed data, performed statistical analysis, interpreted the results, and drafted and edited the manuscript. SN, NK, HO, YF, TM and SO analysed mitochondrial genotype, heteroplasmy and taurine modification. KN01 Study Members collected data for this study. All authors approved the submission.

Funding: This study was funded by Research on Rare and Intractable Diseases, Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (H24-Nanchitou(Nan)-Ippan-068) and by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under grant numbers JP15ek0109093h0001, JP16ek0109093h0002 and JP17ek0109093h0003.

Disclaimer: The sponsors played no role in the study design; the collection, analysis and the interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: YS reports the following research grants: Intramural Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders from the National Center of Neurology and Psychiatry (26-8), Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (C-24591281, C-26461285) and by research project grants from Kawasaki Medical School (23-T1, 26-T1).

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Each institutional review board (IRB) of individual 10 clinical institutions participating in this trial approved all trial procedures.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Collaborators: KN01 Study Group includes the following people: H Onoue, K Kaida (National Defense Medical College Hospital, Tokyo, Japan), K Sato, T Uchiyama (Seirei Hamamatsu General Hospital, Shizuoka, Japan), A Ueda, T Mutoh (Fujita Health University School Hospital, Aichi, Japan), M Nakamura (National Hospital Organization Kyoto Medical Center, Kyoto, Japan), K Nishida, I Funakawa (National Hospital Organization Hyogo-Chuo National Hospital, Hyogo, Japan), A Ogawa (Chikushi Hospital, Fukuoka University, Fukuoka, Japan), R Nakata, H Shiraishi, A Tsujino (Nagasaki University Hospital, Nagasaki, Japan), T Takahashi and M Matsumoto (Hiroshima University Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan).

Contributor Information

on behalf of the KN01 Study Group:

H Onoue, K Kaida, K Sato, T Uchiyama, A Ueda, T Mutoh, M Nakamura, K Nishida, I Funakawa, A Ogawa, R Nakata, H Shiraishi, A Tsujino, T Takahashi, and M Matsumoto

Collaborators: on behalf of the KN01 Study Group

References

- 1. Pavlakis SG, Phillips PC, DiMauro S, et al. Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes: a distinctive clinical syndrome. Ann Neurol 1984;16:481–8. 10.1002/ana.410160409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goto Y, Nonaka I, Horai S. A mutation in the tRNA(Leu)(UUR) gene associated with the MELAS subgroup of mitochondrial encephalomyopathies. Nature 1990;348:651–3. 10.1038/348651a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koopman WJ, Willems PH, Smeitink JA, et al. Monogenic mitochondrial disorders. N Engl J Med 2012;366:1132–41. 10.1056/NEJMra1012478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ohama E, Ohara S, Ikuta F, et al. Mitochondrial angiopathy in cerebral blood vessels of mitochondrial encephalomyopathy. Acta Neuropathol 1987;74:226–33. 10.1007/BF00688185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DiMauro S, Melas HM : Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Genereviews(R). Seattle (WA), 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yatsuga S, Povalko N, Nishioka J, et al. MELAS: a nationwide prospective cohort study of 96 patients in Japan. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012;1820:619–24. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaufmann P, Engelstad K, Wei Y, et al. Natural history of MELAS associated with mitochondrial DNA m.3243A>G genotype. Neurology 2011;77:1965–71. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823a0c7f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foswiki. MITOMAP: reported mitochondrial DNA base substitution diseases: rRNA/tRNA mutations. https://www.mitomap.org/foswiki/bin/view/MITOMAP/MutationsRNA

- 9. Foswiki. MITOMAP: Reported mitochondrial DNA base substitution diseases: coding and control region point mutations. https://www.mitomap.org/foswiki/bin/view/MITOMAP/MutationsCodingControl

- 10. Kobayashi Y, Momoi MY, Tominaga K, et al. A point mutation in the mitochondrial tRNA(Leu)(UUR) gene in MELAS (mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes). Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1990;173:816–22. 10.1016/S0006-291X(05)80860-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goto Y, Nonaka I, Horai S. A new mtDNA mutation associated with mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS). Biochim Biophys Acta 1991;1097:238–40. 10.1016/0925-4439(91)90042-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Crick FH. Codon–anticodon pairing: the wobble hypothesis. J Mol Biol 1966;19:548–55. 10.1016/S0022-2836(66)80022-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yasukawa T, Suzuki T, Ueda T, et al. Modification defect at anticodon wobble nucleotide of mitochondrial tRNAs(Leu)(UUR) with pathogenic mutations of mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes. J Biol Chem 2000;275:4251–7. 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yasukawa T, Suzuki T, Ishii N, et al. Wobble modification defect in tRNA disturbs codon–anticodon interaction in a mitochondrial disease. Embo J 2001;20:4794–802. 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kirino Y, Yasukawa T, Ohta S, et al. Codon-specific translational defect caused by a wobble modification deficiency in mutant tRNA from a human mitochondrial disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:15070–5. 10.1073/pnas.0405173101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fakruddin M, Wei FY, Suzuki T, et al. Defective mitochondrial tRNA taurine modification activates global proteostress and leads to mitochondrial disease. Cell Rep 2018;22:482–96. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Torres AG, Batlle E, Ribas de Pouplana L. Role of tRNA modifications in human diseases. Trends Mol Med 2014;20:306–14. 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rikimaru M, Ohsawa Y, Wolf AM, et al. Taurine ameliorates impaired the mitochondrial function and prevents stroke-like episodes in patients with MELAS. Intern Med 2012;51:3351–7. 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hirano M, Ricci E, Koenigsberger MR, et al. MELAS: an original case and clinical criteria for diagnosis. Neuromuscul Disord 1992;2:125–35. 10.1016/0960-8966(92)90045-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hirano M, Pavlakis SG. Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes (MELAS): current concepts. J Child Neurol 1994;9:4–13. 10.1177/088307389400900102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kirino Y, Goto Y, Campos Y, et al. Specific correlation between the wobble modification deficiency in mutant tRNAs and the clinical features of a human mitochondrial disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:7127–32. 10.1073/pnas.0500563102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stacpoole PW. Why are there no proven therapies for genetic mitochondrial diseases? Mitochondrion 2011;11:679–85. 10.1016/j.mito.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Glover EI, Martin J, Maher A, et al. A randomized trial of coenzyme Q10 in mitochondrial disorders. Muscle Nerve 2010;42:739–48. 10.1002/mus.21758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koga Y, Akita Y, Nishioka J, et al. L-Arginine improves the symptoms of strokelike episodes in MELAS. Neurology 2005;64:710–2. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000151976.60624.01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ministerial Ordinance on Good Clinical Practice for Drugs. Ordinance of the Ministry of Health and Welfare No. 28, March 27, 1997. Last amended by the Ordinance of Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare No. 161, December 28, 2012. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000152996.pdf (accessed 2 May 2016).

- 26. Chinnery PF, Bindoff LA. European Neuromuscular Center. 116th ENMC international workshop: the treatment of mitochondrial disorders, 14th–16th March 2003, Naarden, The Netherlands. Neuromuscul Disord 2003;13:757–64. 10.1016/S0960-8966(03)00097-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schaffer SW, Shimada-Takaura K, Jong CJ, et al. Impaired energy metabolism of the taurine‑deficient heart. Amino Acids 2016;48:549–58. 10.1007/s00726-015-2110-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huxtable RJ. Physiological actions of taurine. Physiol Rev 1992;72:101–63. 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.1.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Majamaa-Voltti KA, Winqvist S, Remes AM, et al. A 3-year clinical follow-up of adult patients with 3243A>G in mitochondrial DNA. Neurology 2006;66:1470–5. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216136.61640.79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

jnnp-2018-317964supp001.pdf (8.1MB, pdf)