Abstract

Religiosity is associated with sexual behavior in adolescence; however, religiosity is a multidimensional construct, and it is not clear how different patterns of religiosity may differentially predict sexual behaviors and romantic relationships. We apply latent class analysis to nationally representative data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health; N = 10,149) to examine a) what religiosity profiles exist among adolescents and b) how they predict sexual behavior and romantic relationship status in adolescence and young adulthood. Religiosity in multiple domains was associated with lesser odds of sexual behavior compared to profiles marked by only affiliation, private, or public religiosity. Findings suggest examining multiple facets of religiosity together is important for understanding how religiosity is associated with sexual behavior.

Keywords: sexual behavior, religiosity, latent class analysis

Religion is an important source of socialization for adolescents, and can provide a set of guidelines to follow in a number of domains, including romantic relationships and sexual behaviors. Research has documented that adolescents’ religiosity, or their relationship to a particular doctrine or faith tradition (King & Boyatzis, 2004) is associated with sexual behaviors in adolescence (Rostosky, Wilcox, Comer Wright, & Randall, 2004). Researchers have increasingly suggested that religiosity is a multidimensional construct, yet research on religiosity and sexual behavior typically does not take this conceptualization into account. Thus, it is unclear which aspects of religiosity are most important for relationships and sexual behavior, as well as how different facets may interact to predict outcomes. In this study, we apply latent class analysis (LCA) to nationally representative U.S. data to determine 1) what profiles (latent classes) of adolescent religiosity are present among adolescents 2) what demographic factors predict membership in these religiosity classes and 3) how these classes are associated with adolescent and young adult sexual behavior and romantic relationship status outcomes.

Religiosity and adolescent sexual and romantic behaviors

Religion is an important influence in the lives of youth, with the majority of adolescents in the U.S. believing religion is important and attending religious service with some frequency (Smith & Denton, 2005; Twenge, Exline, Grubbs, Sastry, & Campbell, 2015). Smith (2003) theorizes a number of factors that may explain the effects of religiosity on youth outcomes, including establishing a moral order, learning competencies, and gaining social and organizational ties. These different factors may explain different pathways by which religiosity is associated with sexual behavior. Related to moral order, religion can set up a series of guidelines to follow about romantic relationships and sexual behavior. Judeo-Christian religions practiced by many in the U.S. typically emphasize remaining abstinence until marriage, and, in some cases, the relational aspects of sexual behavior (Rostosky et al., 2003), suggesting that religion may socialize individuals against behaviors like premarital sex, non-relationship sex, and cohabitation. In addition, because premarital sexual behavior is generally proscribed and the importance of family is emphasized, religious individuals may be more supportive of early marriage (Stolzenberg, Blair-Loy, & Waite, 1995). In addition to direct teachings, religion may also emphasize this moral order indirectly by providing role models who may model relationships for adolescence (Smith 2003). Religion may also help adolescents earn competencies and skills, such as community service, leadership skills, coping skills, and cultural capital (Smith 2003). These sorts of skills are associated with lesser odds of engaging in sexual behavior (Charles & Blum, 2008; Gavin et al., 2010). Finally, religious organizations provide social and organizational ties, such as access to a cross-generational support network. Research has shown that close relationships with adults are associated with lesser odds of engaging in sexual intercourse (Vesely et al., 2004). Thus, there are a number of ways in which religiosity may discourage non-marital sexual behaviors and model committed romantic relationships.

Research has generally supported the idea that religion is protective against adolescent sexual behaviors (see Rostosky et al., 2004; Rew & Wong, 2006 for review). Adolescents who are more religious are less likely to initiate sexual intercourse (Crockett, Bingham, Chopak, & Vicary, 1996; Hardy & Raffaelli, 2003; Lefkowitz, Gillen, Shearer, & Boone, 2004; Meier, 2003; Nonnemaker, McNeely, & Blum, 2003). When sexually active, they have fewer sexual partners (Gold et al., 2010; Lefkowitz et al., 2004) and are less likely to engage in non-relationship sex (Penhollow, 2007). In addition, adolescents who are more religious are more likely to marry and less likely to cohabit in young adulthood (Meier & Allen, 2009; Uecker, 2014). However, not all studies have found effects of religiosity on sexual behaviors (see Rostosky et al., 2004; Zimmer-Gembeck & Helfand, 2008).

Prior studies have used different measures of religiosity, including denominational affiliation (Bearman & Bruecker, 1999; Beck, Cole, & Hammond, 1991; Sheeran et al., 1993), public religiosity, (e.g., attendance at religious services; Crockett et al.,1996; Lefkowitz et al., 2004; Nonnemaker et al., 2003; Sheeran et al., 1993), and private beliefs (e.g., importance of religiosity in daily life; Lefkowitz et al., 2004; Nonnemaker et al., 2003; Sheeran et al., 1993). However, most studies have used measures of religiosity that examine single constructs, although religiosity is multidimensional (Rostosky et al., 2004; Yonker, Schnabelracuh, & DeHaan, 2012). Some studies have used composite scores that include both public and private religiosity (Bearman & Bruckner, 2001; Hardy & Raffaelli, 2003; Meier, 2003; Rostosky, Regnerus, & Comer Wright, 2003; Whitbeck, Yoder, Hoyt, & Conger, 1999). Although these measures include multiple domains, they are treated as a single construct; thus, it is unclear how different aspects of religiosity, and their intersections, may differentially influence outcomes.

A Person-Centered Approach to Religiosity

Researchers have long conceptualized religiosity as including multiple components, such as belief, experience, practice, knowledge, commitment, orthodoxy, and consequences (Chalfant Beckley, & Palmer, 1994; Cornwall, Albrecht, Cunningham, & Pitcher, 1985; De Jong, Faulkner, & Warland, 1976; King & Boyatzis, 2004). For example, De Jong and colleagues (1976) described six aspects of religiosity: belief, experience, religious practice, religious knowledge, individual moral consequences, and social consequences. Cornwall and colleagues (1986) present a conceptual model of religiosity which places different aspects of religion at the intersections of the components of belief, commitment, and behavior, and the two modes of personal and institutional. This distinction between personal/private and public/institutional aspects of religiosity is evident in research examining associations between adolescent religiosity and sexual behavior, as several studies have examined the differential impact of public and private aspects of religiosity (e.g., Lefkowitz et al., 2004; Nonnemaker et al., 2003; Sheeren et al., 1993; Vasilenko, Iannuci, Zheng, & Lefkowitz, 2013) or have used composite measures (e.g., Hardy & Raffaelli, 2003; Meier, 2003; Rostosky, Regnerus, & Comer Wright, 2003). However, less is known about what patterns of these components may characterize adolescents’ religiosity, or how the intersections of these components may predict sexual behaviors and relationships.

One approach to understanding the multidimensionality of religiosity is person-centered methods like latent class analysis (LCA; Collins & Lanza, 2008). While a traditional, variable-centered approach involves assessing the effect of individual dimensions separately, person-centered approaches examine these dimensions simultaneously by uncovering profiles marked by different patterns of beliefs and behaviors. This allows an understanding of how different dimensions co-occur in the population, as well as how the interaction of different facets may be associated with outcomes. For example, this approach can not only identify individuals who are highly religious or non-religious, but more nuanced profiles such as those with private but not public religiosity or who are religiously active but have less conservative beliefs. By examining these profiles, researchers can better understand what aspects of religiosity and what particular combinations of factors may be most closely associated with outcomes, which may give insight into the mixed results of studies of the associations between religiosity and sexual behavior.

A number of recent studies have used a person-centered approach to document profiles of religiosity in adolescents and young adults (Good, Willoughby, & Busseri, 2011; Jankowski et al., 2015; Pearce, Foster, & Hardie, 2013; Salas-Wright, Vaughn, Hodge, & Perron, 2012; Smith & Denton, 2005). Although the profiles in these studies vary based upon the specific religiosity variables included, they tend to differentiate profiles marked by consistently high or low religiosity, as well as profiles with high religiosity in only certain domains, such as primarily private aspects of religiosity or a higher degree of participation in public religious activities. For example, multiple studies have uncovered classes with high religiosity in all areas, low religiosity in all areas, plus a pattern marked by primarily private religious practice (Good et al., 2011; Salas-Wright et al, 2012). Although religiosity class membership predicts outcomes like substance use (Jankowski et al., 2015; Salas-Wright et al, 2012), to our knowledge no study has examined how multidimensional profiles of religiosity predict sexual and relationship behaviors.

In this study we examine how multidimensional profiles of religiosity are associated with adolescent and young adult sexual behaviors and romantic relationships in a large, nationally representative longitudinal study of adolescents in the U.S. We have the following aims:

To uncover latent classes of adolescent religiosity based on affiliation, beliefs, importance of religion, and attendance at religious services and activities.

To examine demographic factors that predict membership in these latent classes.

To examine how these adolescent religiosity profiles predict sexual behaviors and relationship status one year later and in young adulthood.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data are from the contractual sample of Add Health (Harris, 2011), which includes a larger number of participants and additional variables compared to the public data. Eighty high schools and associated middle schools were sampled, employing a clustered sampling design to ensure that the sample was representative of schools in the United States. Participants completed in-school and in-home interviews in 1994–1995 (WI; 7th through 12th grade) with follow-up interviews during 1995–1996 (WII; 12th graders not interviewed), 2001–2002 (WIII; ages 18–24) and 2007–2008 (WIV; ages 25–32). About 80% of participants from the WI sample participated in each of the later waves. Because this study examined how WI religiosity predicted sexual behaviors and relationship status at WII and WIII, we included individuals who had data from WI-III. The analytic sample was more likely to be white, less likely to be Hispanic/Latino, or African American, more likely to be female, and less religious on all indicators if religiosity then the full sample, though these differences were relatively small and significant due to the large sample size. In addition, participants in the analytic sample were younger due to WI 12th graders not being included in WII. The analytic sample contained 10,149 individuals (52.8% female, 20.1% African American, 16.0% Hispanic/Latino, 6.5% Asian, 2.3% other race/ethnicity; 5.6% sexual minority identity; Mage at WI = 15.6, SD = 1.5). Note that we included participants who reported a non-heterosexual sexual attraction, because sexual minority individuals often engage in sexual behaviors with other sex partners (Saewyc et al., 2008). In terms of affiliation, 11.6% reported no religion, 26.0% Catholic, 23.3% Mainline Protestant, 12% Black Protestant, 19.6% Evangelical and 7.2% Other religion).

Measures

Latent class indicators.

Our religiosity classes included measures of affiliation, beliefs, importance of religion, prayer, and religious service attendance, consistent with theoretical models of religiosity (e.g. Cornwall et al., 1986) and the types of measures used in prior variable-centered studies of this topic. We used 6 measures of religiosity as indicators in our latent class model, which were measured at WI. Because many variables were skewed and did not completely capture the full range of the scale, we dichotomized all variables to indicate a high or low endorsement of the construct. Affiliation was a measure of whether an individual reported an affiliation with any religion (88%). If individuals did not report any affiliation, they were not asked additional religion questions, and were coded as having low religiosity on these additional items. Two variables measured public religious behaviors. Religious service attendance measured how often adolescents reported attending religious services, rated on a 4-point scale from never to once a week or more. Participants were coded as having regular attendance if they reported attending at least monthly (60%). The youth activities item was a measure of how often participants attended activities for teenagers, such as youth groups, which was rated on the same 4-point scale as religious service attendance, with regular attendance coded as monthly or more (39%). Importance of religion was a single item assessing how important religion is to the adolescent, coded on a 4 point scale from not important at all to very important. Participants were coded as believing religion is important if they answered very important to somewhat important (78%). Regular prayer was coded from a measure of how often an individual prayed, rated on a 5-point scale from never to daily. Participants were coded as praying regularly if they reported weekly or more (64%). Finally, belief in scriptures, a measure of conservative beliefs (cf. Miller & Gur, 2002) asked a yes/no question about whether participants believed their religion’s sacred scriptures are the word of god without any mistakes (68%).

Outcomes.

We examined sexual behavior and relationship status outcomes at WII (adolescent) and WIII (young adult). The same sexual behavior items were used at both waves. Past-year sex was an indicator of whether the participant engaged in vaginal intercourse in the last 12 months, and whether they did so with a single partner or multiple partners. In WII, participants who reported ever having sexual intercourse were asked the date of their most recent sex. In addition, participants were asked a series of questions about whether they had sex with romantic and non-romantic partners, which were used to determine the number of sexual partners. In WIII, participants were asked if they ever had intercourse, and if so, completed a series of follow-up questions, including how many partners they had in the past year. Responses were trichotomized to indicate no sex in the past year, sex with a single partner only (16% WII, 43% WIII), and sex with multiple partners (9% WII, 28% WIII). Non-relationship sex was a measure of whether participants reported sex in the past year with a partner they were not in a romantic relationship with (17% WII, 28% WIII). In WII, participants were asked how many people other than romantic partners they had sex with in the past year. In WIII, this variable was constructed from a series of questions asking each of the participants about their sexual partners in the past year, with only sex with opposite-sex partners included in these analyses.

At WII, we examined whether the individual was in a romantic relationship based on a single item asking participants if they were in a romantic relationship in the past year (44%). At WIII, we examined two relationship status variables Marriage indicates whether the participant reported having ever been married (16%). Cohabitation measured whether an individual lived with any romantic partner they had not married (37%).

Demographic Predictors/Controls.

We examined several predictors of class membership, measured at WI. Gender was a self-reported being male or female (female = 1). Race/ethnicity was measured with 4 dummy-coded variables (Hispanic/Latino (HL); non-HL Black; non-HL Asian; non-HL other, with non-HL White as the reference group). Age indicated a participants’ age at W1. Mother’s education indicated whether or not the adolescent’s mother had completed any schooling after high school (49%), and was used as a proxy for SES. Sexual minority status assessed whether the participant identified as gay/lesbian or bisexual. We also examined how profiles differed by denominational affiliation, using categories from the Pew Research Center’s report on religiosity in the United States (Pew Research Center, 2015)

Statistical Analyses

First, we modeled classes based on six indicators of religiosity using Latent Gold (Vermunt & Madgison, 2015). We selected the optimal number of latent classes based on information criteria (Akike Information Criteria, AIC and Bayesian Information Criteria, BIC) and interpretability. Note that participants were included in the LCA model if they had valid information on at least one religiosity indicator, as LCA uses full information maximum likelihood. Next, we examined correlates of class membership using the BCH three-step approach (Bolck, Croon, & Hagenaars, 2004; Vermunt 2010). In this approach, the LCA model is run, and each participants’ probability of membership in each latent class is saved. Analyses of covariates and outcomes are then weighted by these probabilities, which provides less biased results than classify-analyze approaches as it account for the uncertainty in class assignment. We examined how class membership was predicted by gender, race/ethnicity, age, and mother’s education and religious affiliation. Finally, we examined how class membership was associated with sexual behavior and relationship status outcomes, controlling for demographic covariates. We included weights that account for study design and attrition in all analyses in order to ensure results were more representative of the population.

Results

Interpretation of Latent Classes

We fit models with one through eight classes. Both AIC and BIC suggested a 5-class model, and classes in this model were all differentiated from each other and interpretable. Thus, we chose the 5-class model. Table 1 shows prevalences and item response probabilities, presented in order of prevalence in the population. The largest class, called Multidimensional Religious (48%), was marked by high probability or endorsing variables assessing all aspects of religiosity. Next, the Primarily Private class (27%) was affiliated with a religion and had high probabilities of viewing religion as important, prayer, and conservative beliefs. The Not Religious class (13%) had low probability of endorsing all religiosity items, whereas the Primarily Affiliation class (8%) had low probability items other than endorsing an affiliation with a religious denomination. Finally, the Primarily Public class (3%) had relatively high probabilities of a religious affiliation, religious service attendance, and youth activities attendance, but low probabilities of prayer, importance of religion and conservative beliefs.

Table 1.

Latent Class Prevelances and Item-Response Probabilities for Eight Class Model of Religiosity

| Class 1: Multi-dimensional Religious | Class 2: Primarily Private | Class 3: Not Religious | Class 4: Primarily Affiliation | Class 5: Primarily Public | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Latent Class Prevalences | 48.2% | 27.2% | 13.4% | 8.4% | 2.8% |

| Estimated Class Size | 4,892 | 2,740 | 1,360 | 853 | 284 |

| Indicators | |||||

| Religious Affiliation | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.03 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Service Attendance | 0.99 | 0.31 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.64 |

| Youth Activities | 0.69 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.59 |

| Importance of Religion | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.47 |

| Regular Prayer | 0.92 | 0.58 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 0.37 |

| Belief in Scriptures | 0.89 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 0.36 | 0.29 |

Note. Bold indicates item response probabilities over .5.

Latent Class Membership and Demographic Factors

Percentages of individuals in each latent class by demographic characteristics are presented in Table 2. All demographic characteristics examined were significantly associated with class membership (p < .05). Women were overrepresented in the Multidimensional Religious Class compared to men, whereas a higher percentage of men were in all other classes. Black adolescents were overrepresented in the Multidimensional Religious class compared to other groups, and were underrepresented in most other classes, particularly the Primarily Affiliation and Primarily Public classes. Asians were also overrepresented in the Multidimensional Religious class. Participants whose mother completed some college were more likely to be in the Multidimensional Religious class and Primarily Public class and less likely to be in the Primarily Private and Not Religious classes. Individuals in the Primarily Affiliation class were oldest, on average, and those in the Multidimensional Religious and Primarily Public were the youngest.

Table 2.

Latent Class Membership by Demographic Characteristics

| Class 1: Multi-dimensional Religious | Class 2: Primarily Private | Class 3: Not Religious | Class 4: Primarily Affiliation | Class 5: Primarily Public | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 46.9% | 52.4% | 54.6% | 54.6% | 56.3% |

| Female | 53.1% | 47.6% | 45.4% | 45.4% | 43.7% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 61.9% | 70.0% | 70.5% | 81.4% | 89.9% |

| Black | 19.7% | 11.2% | 14.6% | 3.0% | 3.5% |

| Latino | 12.0% | 14.8% | 9.1% | 9.7% | 6.6% |

| Asian | 4.2% | 2.0% | 3.2% | 3.4% | 0.0% |

| Other Race | 2.2% | 1.7% | 2.6% | 2.3% | 0.0% |

| Mother’s Education | |||||

| No College | 47.9% | 63.1% | 60.8% | 52.3% | 31.8% |

| Some College | 52.1% | 36.9% | 39.2% | 47.6% | 68.2% |

| Sexual Identity | |||||

| Heterosexual | 95.1% | 93.1% | 93.9% | 91.7% | 96.1% |

| Not Heterosexual | 4.9% | 6.9% | 6.1% | 8.3% | 3.9% |

| Mean Age | 15.3 | 15.5 | 15.5 | 15.7 | 15.3 |

Note. For gender, race/ethnicity, mother’s education, and sexual identity, each column represents the percentage of individuals within a given latent class with a particular characteristics (columns sum to 100% for each predictor. For age, the mean age within each latent class is presented.

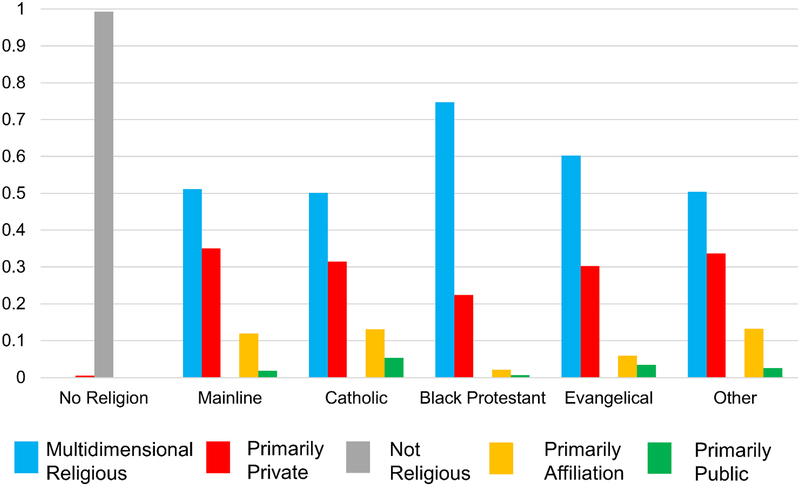

Next, we examined how class membership differed across denominational affiliation categories (Figure 1). Black Protestants had the highest proportion of individuals in the Multidimensional Religious class, followed by Evangelical Protestants. Mainline Protestants and those from other religions were overrepresented in the Primarily Private class. Catholic, Mainline Protestant, and individuals from other religions had the highest proportion of individuals in the Primarily Affiliation class, and Catholics had the highest proportion of being in the Primarily Public class.

Figure 1.

Membership in adolescent religiosity latent classes, by denominational affiliation.

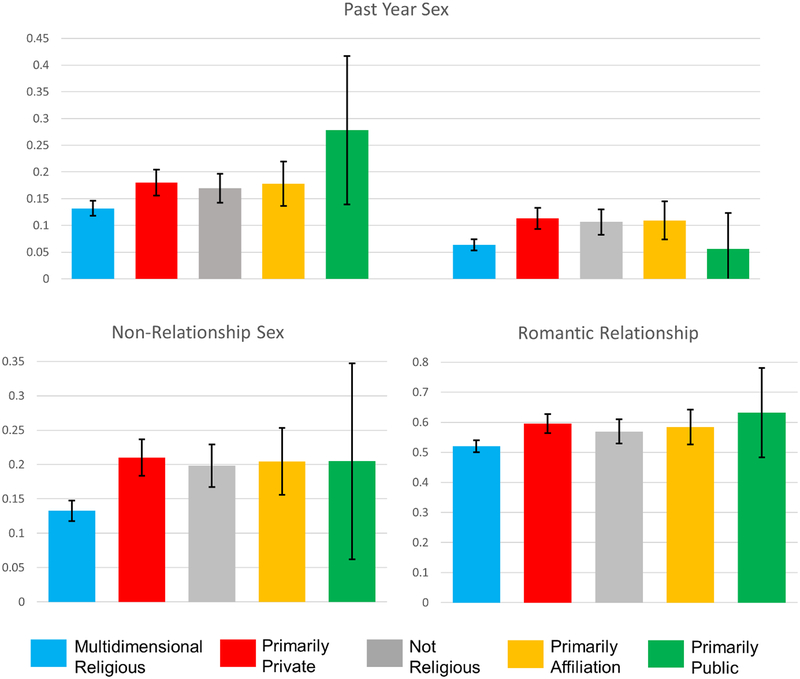

Latent Class Membership Predicting Romantic Relationships and Sexual Behavior

Finally, we examined how class membership predicted sexual behavior and relationship status in adolescence (Table 3) and young adulthood (Table 4). In these tables, the odds ratios for class membership indicate the difference in odds of experiencing an outcome for individuals in a given latent class compared to individuals in the reference class (Multidimensional Religious). In adolescence, class membership was significantly associated with all three outcomes (sex in the past year, non-relationship sex, and being in a relationship). To further explore these results, we plotted the adjusted estimated probability of each adolescent outcome by latent class membership in Figure 2. Individuals in the Multidimensional Religion class had the lowest prevalence of sex with both a single (13%) and multiple partners (6%) compared to all other classes. Individuals in the Primarily Public class had the highest prevalence of sex with a single partner (28%). The Primarily Private, Not Religious, and Primarily Affiliation classes had higher probability of multiple partners than the Multidimensional Religious, but did not differ from each other. These three classes also had a higher prevalence (around 20–22%) of non-relationship sex compared to the Multidimensional Religious class (13%). The Multidimensional Religious class had the lowest prevalence of having a romantic relationship in adolescence (52%).

Table 3.

Models Examining the Effect of Religiosity Latent Classes on Sexual Behaviors and Relationship Status in Adolescence

| Past Year Sex | Non-Relationship Sex | Relationship | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (Single Partner) | 95% CI | OR (Multiple Partners) | 95% CI | Wald | OR | 95% CI | Wald | OR | 95% CI | Wald | |

| Class Membership | 56.74*** | 31.70*** | 17.67*** | ||||||||

| Multidimensional | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||||

| Primarily Private | 1.66 | 1.47–1.88 | 2.18 | 1.87–2.55 | 1.80 | 1.60–2.03 | 1.39 | 1.27–1.52 | |||

| Not Religious | 1.51 | 1.34–1.71 | 1.98 | 1.69–2.6 | 1.67 | 1.47–2.06 | 1.24 | 1.12–1.36 | |||

| Primarily Affiliation | 1.62 | 1.38–1.91 | 2.08 | 1.69–2.57 | 1.74 | 1.09–2.78 | 1.33 | 1.16–1.51 | |||

| Primarily Public | 2.82 | 1.01–4.17 | 1.17 | 0.61–2.22 | 1.74 | 1.08–2.78 | 1.64 | 1.16–2.29 | |||

| Covariates | |||||||||||

| Female | 2.82 | 1.91–4.17 | 1.15 | 1.04–1.27 | 91.27*** | 0.55 | 0.54–0.59 | 59.18*** | 1.59 | 1.50–1.68 | 61.52*** |

| Black | 1.12 | 1.00–1.25 | 1.34 | 1.19–1.53 | 8.20* | 2.56 | 2.33–2.80 | 93.19*** | 0.76 | 0.70–0.82 | 11.38*** |

| Latino | 0.86 | 0.76–0.97 | 0.58 | 0.49–0.69 | 6.0* | 1.07 | 0.95–1.19 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 0.73–0.87 | 5.76* |

| Asian | 0.44 | 0.36–0.55 | 0.35 | 0.25–0.47 | 41.10*** | 0.45 | 0.35–0.57 | 10.31*** | 0.47 | 0.41–0.54 | 25.13*** |

| Other | 0.85 | 0.62–1.15 | 1.47 | 1.09–1.99 | 4.67 | 1.61 | 1.30–2.00 | 4.49* | 0.94 | 0.79–1.12 | 0.10 |

| Mother’s Education | 0.97 | 0.89–1.06 | 0.96 | 0.87–1.07 | 0.02 | 0.85 | 0.78–0.92 | 3.98* | 1.27 | 1.20–1.34 | 15.49*** |

| Sexual Minority Identity | 1.06 | 0.89–1.25 | 1.44 | 1.21–1.73 | 4.36 | 1.83 | 1.61–2.10 | 18.83*** | 1.35 | 1.19–1.53 | 5.27* |

| Age | 1.75 | 1.70–1.82 | 1.74 | 1.70–1.82 | 77.74*** | 1.28 | 1.24–1.31 | 90.40*** | 1.40 | 1.38–1.43 | 271.96*** |

Note. Odds ratios for class membership describe the difference in odds of having a particular outcome for individuals in a given class compared to the Multidimensional Religious class (reference group).

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

Table 4.

Models Examining the Effect of Religiosity Latent Classes on Sexual Behaviors and Relationship Status in Young Adulthood

| Past-Year Sex | Non-Relationship Sex | Marriage | Cohabitation | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (Single Partner) | 95% CI | OR (Multiple Partners) | 95% CI | Wald | OR | 95% CI | Wald | OR | 95% CI | Wald | OR | 95% CI | ||

| Class Membership | 85.36*** | 23.13*** | 13.90** | 84.40*** | ||||||||||

| Multidimensional | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | |||||||||

| Primarily Private | 1.75 | 1.60–1.91 | 2.06 | 1.87–2.27 | 1.43 | 1.29–1.60 | 0.95 | 0.84–1.07 | 1.79 | 1.63–1.95 | ||||

| Not Religious | 1.65 | 1.51–1.81 | 1.66 | 1.66–1.83 | 1.60 | 1.43–1.78 | 0.78 | 0.68–0.89 | 2.29 | 2.08–2.52 | ||||

| Primarily Affiliation | 1.40 | 1.23–1.60 | 1.95 | 1.69–2.24 | 1.43 | 1.22–1.66 | 0.54 | 0.44–0.66 | 1.58 | 1.38–1.80 | ||||

| Primarily Public | 0.71 | 0.51–0.98 | 1.19 | 0.86–1.66 | 1.75 | 1.15–2.64 | 0.41 | 0.22–0.74 | 0.85 | 0.58–1.2 | ||||

| Covariates | ||||||||||||||

| Female | 1.59 | 1.50–1.67 | 0.91 | 0.87–0.97 | 139.72*** | 1.18 | 1.16–2.64 | 27.85*** | 2.33 | 2.15–2.53 | 99.60*** | 1.59 | 1.50–1.69 | 57.76*** |

| Black | 1.10 | 1.02–1.19 | 1.86 | 1.73–2.02 | 85.11*** | 0.97 | 0.87–1.08 | 2.84 | 0.43 | 0.38–0.49 | 37.93*** | 0.99 | 0.91–1.07 | 0.01 |

| Latino | 0.91 | 0.85–0.99 | 0.81 | 0.74–0.88 | 5.76 | 0.37 | 0.29–0.46 | 0.07 | 1.12 | 1.00–1.26 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.71–0.85 | 6.30* |

| Asian | 0.59 | 0.54–0.65 | 0.34 | 0.29–0.38 | 65.95*** | 0.93 | 0.75–1.16 | 17.24*** | 0.53 | 0.42–0.67 | 6.94* | 0.50 | 0.42–0.58 | 18.78*** |

| Other | 0.79 | 0.68–0.93 | 1.19 | 1.00–1.40 | 6.79* | 1.06 | 0.99–1.14 | 0.10 | 1.06 | 0.80–1.39 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 0.68–0.99 | 0.96 |

| Mother’s Education | 0.86 | 0.81–0.91 | 1.01 | 0.95–1.08 | 12.98** | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 0.69 | 0.56 | 0.52–0.61 | 44.62*** | 0.64 | 0.60–0.68 | 51.78*** |

| Sexual Minority Identity | 0.96 | 0.86–1.09 | 1.01 | 0.89–1.14 | 0.19 | 1.12 | 0.97–1.29 | 0.52 | 0.99 | 0.82–1.19 | 0.00 | 1.18 | 1.04–1.33 | 1.75 |

| Age | 1.15 | 1.13–1.17 | 1.06 | 1.06–1.08 | 60.21*** | 0.99 | 0.97–1.01 | 0.10 | 1.54 | 1.50–1.58 | 230.42*** | 1.29 | 1.26–1.31 | 152.80*** |

Note. Odds ratios for class membership describe the difference in odds of having a particular outcome for individuals in a given class compared to the Multidimensional Religious class (reference group).

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

Figure 2.

Adolescent sexual behaviors and romantic relationship status, by religiosity latent class membership.

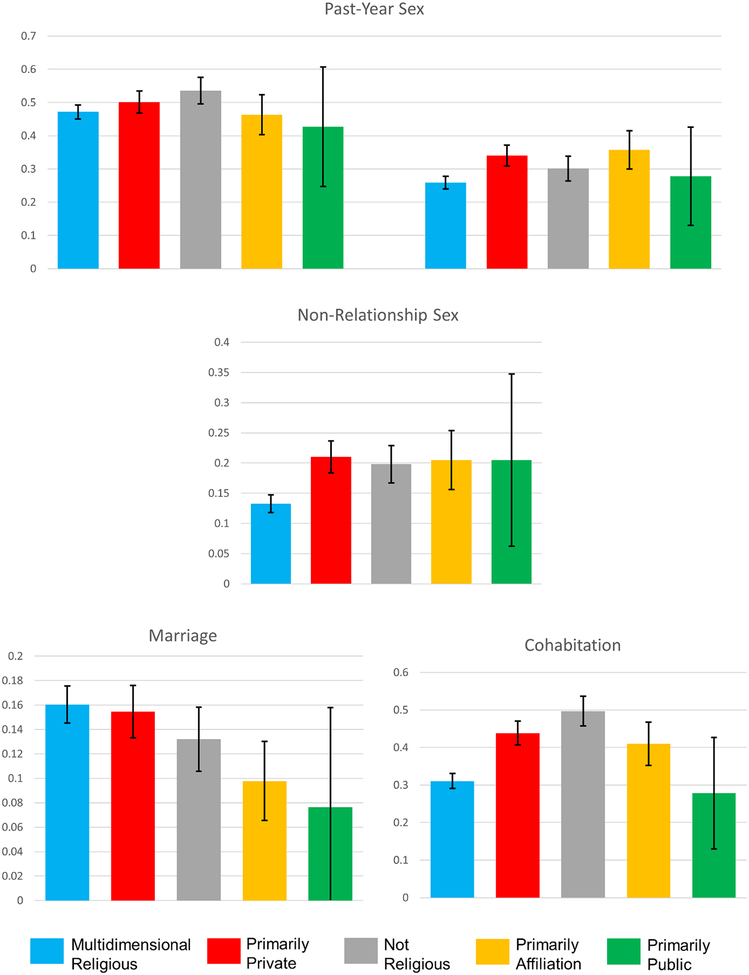

All young adult outcomes were significantly predicted by latent class membership (Table 4). To further explore these results, we plotted the adjusted estimated probability of each adolescent outcome by latent class membership in Figure 2. The Multidimensional Religious class was lowest in past-year sex with single and multiple partners and non-relationship sex. Individuals in the Not Religious class in adolescence were most likely to have sex with a single partner in young adulthood (54%), whereas individuals in the Primarily Private and Primarily Affiliation class had the highest prevalence of sex with multiple partners. Rates of marriage were highest for the Multidimensional Religious and Primarily Private classes, and were significantly higher than those for the Primarily Affiliation class. Individuals in the Primarily Private, Not Religious, and Primarily Affiliation were more likely to cohabit than those in the Multidimensional Religious class.

Discussion

This study examined profiles of religiosity in U.S. adolescents, and how these profiles predicted sexual behaviors and relationship status during adolescence and young adulthood. Our results were consistent with prior research (e.g., Smith & Denton, 2005) suggesting that many U.S. adolescents are high on multiple facets of religiosity. The largest class, Multidimensional Religious, contained nearly half of participants, and was marked by high endorsement of all religiosity items. Thus, a large portion of adolescents attend religious services and youth activities, see their religion as important to them, and engage in private behaviors like regular prayer. However, a number of other smaller profiles were also uncovered, suggesting differing profiles of religiosity. For example, about one-third of adolescents were in the Not Religious or Primarily Affiliation classes, which were marked by a lack of religious behavior and endorsement of the importance of religion. Thus, while many adolescents are highly religious, a sizable minority also are not very religious as defined by the variables in this study.

In addition to these classes with relative consistency across various measures of behavior and beliefs, we also uncovered two classes marked by profiles with less consistency. As in other LCA studies (Jankowski et al., 2015; Salas-Wright et al., 2012), we found a class termed Primarily Private, in which individuals felt religion was important, endorsed more conservative religious beliefs, and prayed regularly, but did not attend religious services or activities. In addition, we uncovered a small class, Public Religiosity, in which adolescents were likely to attend religious services and youth activities regularly, but did not view religion as important or pray often. Individuals in this class were primarily white, and more likely to have a mother who attended college. They also had less consistent patterns of sexual behavior and romantic relationships over time compared to individuals in other classes. For example, they had the highest rates of past-year sex with a single partner and being in a romantic relationship in adolescence and the highest rates of non-relationship sex in young adulthood, but also the lowest rates of past-year sex, marriage and cohabitation in young adulthood. This may suggest deviance from developmental norms at different ages. Engaging in these behaviors at early ages may be seen as off-time and more problematic. However, in young adulthood when sexual behavior is less normative, being less likely to engage in sex and form marital or cohabiting relationships may suggest issues in forming intimate relationships. However, why this particular class may be associated with these behavioral patterns is unclear. This class was only about 3% of the population and not found in other studies, so future research should attempt to better understand these individuals and which particular populations they may be most prevalent in.

There were differences in class membership by demographic factors. Consistent with prior research which suggests that female adolescents score higher on most measures of religiosity (Buchko, 2004; Smith, 2004), women were more likely to be in the Multidimensional Religion class, and less likely to be in the other classes. Explanations of this greater religiosity for females include socialization to be more nurturing and submissive and to take less risks, which could lead female adolescents to commit to a religion (Miller & Stark, 2002). Black adolescents, as well as individuals with a Black Protestant denominational affiliation, were also more likely to be in the Multidimensional Religious class compared to other racial/ethnic groups and denominations. The black church serves a number of different functions that may be distinct from other ethnic groups, including providing a sense of community and group identity (Brega & Coleman, 1999). Religiosity is also associated with black identity development (Hughes & Demo, 1990). Thus, religiosity may be more integrated into black adolescents’ community and sense of self which may serve to reinforce both public and private religiosity.

We also found that religiosity latent classes were associated with sexual behaviors and relationship status in adolescence and in young adulthood. With a few exceptions, associations between class membership and sexual behavior outcomes looked similar across adolescence and young adulthood, with the Multidimensional Religious class having lesser odds of engaging in these behaviors compared to the other classes, which in turn had similar rates. This is similar to prior studies which have generally found that only a profile marked by high endorsement of multiple measures of religiosity is associated with lesser odds of substance use (Jankowski et al., 2015; Salas-Wright, 2012). This suggests that being highly religious in multiple areas is associated with less sexual behavior than single aspects, such as public or private religiosity alone. The fact that private religiosity was not protective against sexual behavior is consistent with perspectives on religion as a social control, which suggest the importance of socialization into a religious community in predicting behaviors (Regnerus 2003; Salas-Wright et al., 2012). However, in this study, being in the Primarily Public class was not associated with lesser odds of sexual behavior, suggesting that that internalization of religious beliefs is also important. It is possible that adolescents in Private and Public religiosity classes are more likely to use compartmentalization, by which they maintain different aspects of their behavior and identify in different spheres, allowing them to reconcile conflicts between their religiosity and sexual behaviors (Stoppa, Espinosa-Hernandez, Gillen, 2014). However, for individuals in the Multidimensional Religious class, their religious identity may be more congruent across all areas, which may be protective against sexual behavior, as multiple dimensions of religious influence may be interrelated and work to reinforce each other (Smith, 2003). In addition, these associations were mostly similar across both adolescence and adulthood, suggesting that individuals’ profiles of religiosity at younger ages may influence their behaviors into adulthood.

Findings for the relationship status outcomes were somewhat more nuanced. Adolescent relationship status had a somewhat similar pattern to the sexual behaviors, suggesting that having a multidimensional religiosity profile may be similarly associated with lesser odds of an early romantic relationship, perhaps over concerns that such relationships could also lead to sexual behaviors. However, different profiles are more differentially associated with the young adult relationship outcomes. Individuals in both the Multidimensional and Privately Religious classes had similarly high rates of marriages in young adulthood (ages 18–24), suggesting that earlier marriage may be more attractive to individuals who view religion as more important and have more conservative beliefs, regardless of their religious service attendance. For cohabitation, although the Multidimensional Religious class had lower rates than Privately Religious, Not Religious, and in Primarily Affiliation classes, there was variation between these three groups, with the Not Religious class having the highest rates of cohabitation. This suggests that for cohabitation specifically, having a religious affiliation and/or private religious beliefs is somewhat protective compared to having no religion. This may be because being in a cohabiting relationship is a more public endorsement of engaging in sexual behaviors, whereas non-marital sexual behaviors in non-cohabiting relationships may be more private. This public aspect may create more stigma around cohabitation, leading it to be endorsed by individuals who are religious but less affiliated with a religious community.

These findings provide a number of insights into the study of both religious influences and development of romantic relationships and sexual behavior. First, it underscores the heterogeneous nature of adolescent religiosity by showing that adolescents have several distinct profiles based on their public and private behaviors, beliefs, and affiliation. This is important to recognize in future studies, as much of the research on the influence of religiosity on sexual behaviors uses a variable centered approach examining individual facets, which may make it more difficult to detect significant findings or to fully understand the associations. This person-centered analysis suggests a possible reason for mixed findings on the associations between individual dimensions of religiosity and sexual behavior; because the strongest effect of religiosity is reserved for adolescents who are religious in multiple dimensions, it is possible that using single items alone may attenuate any potential effects of religiosity. Second, these findings show that the effects of adolescent religiosity predict outcomes in both adolescence and young adulthood, suggesting that adolescent religiosity may have some long-term effects on development. Finally, this research shows that a multidimensional profile of high religiosity in multiple domains may represent a pathway to some domains of sexual health and relationship development. Individuals with this profile are less likely to engage in sexual behavior in adolescence, which may put them at lesser risk of sexually transmitted infections (Kaestle, Halpern, Miller, & Ford, 2005). However, individuals in this class still had relatively high rates of romantic relationships in adolescence, and were the most likely class to be married in young adulthood. This suggests that high multidimensional religiosity may be associated with less sexual risk without impeding relationship development. However, there are a number of other factors that should be considered along with relationship formation; for example, early marriages may be more likely to end in divorce (Lehrer, 1996; Teachman, 2002). Thus, it is important for future research to examine how multiple facets of religiosity are associated with outcomes like relationship dissolution and relationship and sexual satisfaction, in order to fully understand links between religion and both positive and negative sexual and relationship outcomes.

There are a number of limitations of this study that provide areas for future research. First, given that this was a secondary analysis of existing data, we were unable to examine some important aspects of religiosity, such religions’ teachings about sexual behaviors, and adolescents’ belief and understanding of those teachings. In addition, we did not have any adolescent measures of spirituality. Some of our measures, such as the one assessing religious beliefs, may not have fully encompassed the nuances of the construct. Future studies should use theoretical and conceptual models on the nature of religion and spirituality to guide the inclusion of measures into data collection. In addition, we were unable to examine the effect of religiosity on sexual behaviors other than vaginal intercourse, and future research should examine religious influences on oral or anal sex. Second, although the use of longitudinal data is a strength, the cohort assessed in this study may be different from more recent cohorts of adolescents, as research has suggested a decrease in participation in organized religion among youth (Twenge, Exline, Grubbs, Sastry, & Campbell, 2015). In addition, we did not assess changes in religiosity across the waves in this study, and future research could use methods like latent transition analysis (Lanza, Patrick, & Maggs, 2010) to examine changes over time, and how these changes are associated with sexual behavior outcomes. Finally, some studies have documented differences in the effects of religiosity by gender, race/ethnicity, and sexual orientation (Rostosky et al., 2003; Rostosky, Danner, & Riggle, 2007) and future research looking at moderators of the effects of latent class membership would be useful in better understanding if these associations and whether they hold when the intersections of multiple domains of religiosity are considered. In addition, this sample was primarily Christian, and future research should examine the multidimensionality of religiosity in other religions.

Despite these limitations, this study provides new insights into religiosity and sexual behavior in the U.S. First, it documents profiles of religiosity among adolescents in a nationally representative sample, finding that profiles consistently high and low on multiple religiosity are common, but that profiles marked by either private or public religiosity also exist. Second, it demonstrates associations between these profiles and sexual behaviors and relationship status in adolescence and young adulthood. These findings suggest that adolescent religion does predict outcomes into young adulthood, and that being high in multiple aspects of religiosity is protective against sexual behaviors, whereas private or private religiosity or affiliation alone do not predict lesser rates of sexual behaviors compared to individuals who are not religious. These findings provide insight into how religiosity is associated with sexual behavior, which could have implications for theory building and spur future research on the exact mechanisms by which religiosity and sexual behavior are associated.

Figure 3.

Young adult sexual behaviors and romantic relationship status, by religiosity latent class membership.

Acknowledgements.

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project directed by Kathleen Mullan Harris and designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and funded by grant P01-HD31921 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with cooperative funding from 23 other federal agencies and foundations. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Information on how to obtain the Add Health data files is available on the Add Health website (http://www.cpc.unc.edu/addhealth). No direct support was received from grant P01-HD31921 for this analysis. This research and the authors was supported by NIH grant P50 DA039838. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Bearman PS,& Bruckner H (1999). Power in numbers: Peer effects on adolescent girls’ sexual debut and pregnancy. Washington, DC: National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman PS, & Bruckner H (2001). Promising the future: Virginity pledges and first intercourse. American Journal of Sociology, 106, 859–912. doi: 10.1086/320295. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beck SH, Cole BS,& Hammond JA (1991). Religious heritage and premarital sex: Evidence from a national sample of young adults. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 30, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Bolck A, Croon M, & Hagenaars J (2004). Estimating latent structure models with categorical variables: One-step versus three-step estimators. Political Analysis, 12, 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Brega AG, & Coleman LM (1999). Effects of religiosity and racial socialization on subjective stigmatization in African-American adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 223–42. doi: 10.1006/jado.1999.0213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchko KJ (2004). Religious beliefs and practices of college women as compared to college men. Journal of College Student Development, 45, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Chalfant HP, Beckley RE, & Palmer CE (1994). Religion in contemporary society. FE Peacock Pub. [Google Scholar]

- Charles VE, & Blum RW (2008). Core competencies and the prevention of high-risk sexual behavior In Guerra NG & Bradshaw CP (Eds.), Core competencies to prevent problem behaviors and promote positive youth development. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 122, 61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, & Lanza ST (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall M, Albrecht SL, Cunningham PH, & Pitcher BL (1986). The dimensions of religiosity: A conceptual model with an empirical test. Review of Religious Research, 226–244. [Google Scholar]

- Crockett LJ, Bingham RC, Chopak JS, & Vicary JR (1996). Timing of first sexual intercourse: The role of social control, social learning, and problem behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 25, 89–111. doi: 10.1007/BF01537382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong GF, Faulkner JE, & Warland RH (1976). Dimensions of religiosity reconsidered; Evidence from a cross-cultural study. Social Forces, 54(4), 866–889. [Google Scholar]

- Demo DH, & Hughes M (1990). Socialization and racial identity among black Americans. Social Psychology Quarterly. [Google Scholar]

- Gavin LE, Catalano RF, David-ferdon C, Gloppen KM, & Markham CM (2010). A Review of Positive Youth Development Programs That Promote Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46(3), S75–S91. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good M, Willoughby T, & Busseri MA (2011). Stability and change in adolescent spirituality/religiosity: a person-centered approach. Developmental Psychology, 47, 538–550. doi: 10.1037/a0021270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy SA, & Raffaelli M (2003). Adolescent religiosity and sexuality: An investigation of reciprocal influences. Journal of Adolescence, 26, 731–739. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankowski PJ, Hardy SA, Zamboanga BL, Ham LS, Schwartz SJ, Kim SY, … Cano MÁ (2015). Religiousness and Levels of Hazardous Alcohol Use: A Latent Profile Analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 1968–1983. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0302-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King PE, & Boyatzis C (2004). Exploring adolescent spiritual and religious development: Current and future theoretical and empirical perspectives. Applied Developmental Science, 8, 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kaestle CE, Halpern CT, Miller WC, & Ford CA (2005). Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Epidemiology, 161(8), 774–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Patrick ME, & Maggs JL (2010). Latent transition analysis: benefits of a latent variable approach to modeling transitions in substance use. Journal of Drug Issues, 40, 93–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkowitz ES, Gillen MM, Shearer CL, & Boone TL (2004). Religiosity, sexual behaviors, and sexual attitudes during emerging adulthood. Journal of Sex Research, 41, 150–159. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrer EL (1996). The determinants of marital stability: a comparative analysis of first and higher-order marriages. Research in Population Economics, 8, 91–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier AM (2003). Adolescents’ transition to first intercourse, religiosity, and attitudes about sex. Social Forces, 81, 1031–1052. doi: 10.1353/sof.2003.0039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meier AM, & Allen G (2009). Romantic relationships from adolescents to young adulthood: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Sociological Quarterly, 50(2), 308–335.doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2009.01142.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AS, & Stark R (2002). Gender and religiousness: Can socialization explanations be saved? American Journal of Sociology, 107, 1399–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Nonnemaker J, McNeely CA, & Blum RW (2003). Public and private domains of religiosity and adolescent health risk behaviors: Evidence from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. Social Science & Medicine, 57, 2049–2054. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce LD, Foster EM, & Hardie JH (2013). A person-centered examination of adolescent religiosity using latent class analysis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 52, 57–79. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center (2015). America’s Changing Religious Landscape.

- Penhollow T, Young M, & Bailey W (2007). Relationship between Religiosity and “Hooking Up” Behavior. American Journal of Health Education, 38, 338–345. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2007.10598992 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Regnerus MD (2003). Moral communities and adolescent delinquency: Religious contexts and community social control. The Sociological Quarterly, 44, 523–554. [Google Scholar]

- Rew L, & Wong YJ (2006). A systematic review of associations among religiosity/spirituality and adolescent health attitudes and behaviors. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(4), 433–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Regnerus M, & Comer Wright ML (2003). Coital debut: The role of religiosity and sex attitudes in the Add Health survey. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 358–367. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostosky SS, Wilcox BL, Comer Wright ML, & Randall B (2004). The impact of religiosity on adolescent sexual behavior: A review of the evidence. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19, 677–697. doi: 10.1177/0743558403260019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saewyc EM, Poon CS, Homma Y, & Skay CL (2008). Stigma management? The links between enacted stigma and teen pregnancy trends among gay, lesbian, and bisexual students in British Columbia. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 17(3), 123–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas-Wright CP, Vaughn MG, Hodge DR, & Perron BE (2012). Religiosity profiles of American youth in relation to substance use, violence, and delinquency. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 1560–1575. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9761-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeran P, Abrams D, Abraham C, & Spears R (1993). Religiosity and adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behaviour: An empirical study of conceptual issues. European Journal of Social Psychology, 23, 29–52. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2420230104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith C (with Denton ML) (2004). Soul searching: The religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, & Denton ML (2009). Soul searching: The religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoppa TM, Espinosa-Hernández G & Gillen MM (2014). Religion, Spirituality, and Sex: Negotiating Intersections and Potential Conflicts in Emerging Adulthood In Abo-Zena M, & Barry C, (Eds.), Emerging Adults’ Religiousness and Spirituality: Meaning-Making in an Age of Transition (pp. 186–203). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Teachman JD (2002). Stability across cohorts in divorce risk factors. Demography, 39(2), 331–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Exline JJ, Grubbs JB, Sastry R, & Campbell WK (2015). Generational and time period differences in American adolescents’ religious orientation, 1966–2014. PLoS ONE, 10, 1–17. 10.1371/journal.pone.0121454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonker JE, Schnabelrauch C. a., & DeHaan LG (2012). The relationship between spirituality and religiosity on psychological outcomes in adolescents and emerging adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 299–314. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.08.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK (2010). Latent class modeling with covariates: Two improved three-step approaches. Political Analysis, 18, 450–469. [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK, & Magidson J (2016). Upgrade manual for Latent GOLD 5.1. Belmont, Massachusetts: Statistical Innovations Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Vesely SK, Wyatt VH, Oman ROYF, Aspy CB, Kegler MC, Rodine S, … Mcleroy KR (2004). The Potential Protective Effects of Youth Assets From Adolescent Sexual Risk Behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 356–365. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck LB, Yoder KA, Hoyt DR, & Conger RD (1999). Early adolescent sexual activity: A developmental study. Family Relations, 61, 934–946. doi: 10.2307/354014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, & Helfand M (2008). Ten years of longitudinal research on U.S. adolescent sexual behavior: Developmental correlates of sexual intercourse, and the importance of age, gender and ethnic background. Developmental Review, 28(2), 153–224. 10.1016/j.dr.2007.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]