Abstract

Loss of the desmosomal cell-cell adhesion molecule, Desmoglein 1 (Dsg1), has been reported as an indicator of poor prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) overexpressing Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR). It has been well established that EGFR signaling promotes the formation of invadopodia, actin-based protrusions formed by cancer cells to facilitate invasion and metastasis, by activating pathways leading to actin polymerization and ultimately matrix degradation. We previously showed that Dsg1 downregulates EGFR/Erk signaling by interacting with the ErbB2 binding protein Erbin (ErbB2 Interacting Protein) to promote keratinocyte differentiation. Here, we provide evidence that restoring Dsg1 expression in cells derived from HNSCC suppresses invasion by decreasing the number of invadopodia and matrix degradation. Moreover, Dsg1 requires Erbin to downregulate EGFR/Erk signaling and to fully suppress invadopodia formation. Our findings indicate a novel role for Dsg1 in the regulation of invadopodia signaling and provide potential new targets for development of therapies to prevent invadopodia formation and therefore cancer invasion and metastasis.

Implications:

Our work exposes a new pathway by which a desmosomal cadherin called Desmoglein 1, which is lost early in head and neck cancer progression, suppresses cancer cell invadopodia formation by scaffolding ErbB2 Interacting Protein and consequent attenuation of EGF/Erk signaling.

Keywords: Desmosomal cadherins, invasion, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Squamous cell carcinoma comprises more than 90% of cancers of the head and neck (HNSCC), and represents the sixth most common cancer worldwide (1,2). While there have been advances in treating HNSCC patients, the overall survival rate remains low (1). Overexpression of EGFR occurs in more than 90% of HNSCC patients, and correlates with enhanced invasion and nodal metastasis (3,4). Targeted therapy against EGFR is considered one of the most promising molecular therapies for HNSCC; however, single treatment with agents directed against EGFR provides only a modest benefit due in part to development of drug resistance. Mutations in the EGFR gene, altered expression and/or activity of EGFR effectors, or activation of alternate signaling pathways are implicated in acquisition of therapeutic resistance (5,6).

In invasive cancer cells, activation of EGFR and its downstream effectors results in the formation of actin based protrusions known as invadopodia (7). These structures contain an actin-rich core and actin regulatory molecules (e.g cortactin, Tks5, cofilin, Arp2/3, N-WASP, MT1-MMP, among others) (8) that facilitate degradation of the basement membrane and extracellular matrix by the targeted delivery and secretion of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) to sites of invasion. The ability of human cancer cells to form invadopodia has been correlated with their invasiveness, both in vitro and in vivo (9–11), and represents a mechanism by which cancer cells enter into the bloodstream and disseminate to distant organs (12,13). In previous studies, HNSCC have proven to be an excellent model for assessing the role of the EGFR pathway and the actin regulatory machinery in invadopodium dynamics. It has been shown that inhibition of EGFR and downstream effectors such as Src and Erk1/2 reduces the number of invadopodia and matrix degradation by suppressing invadopodia signaling and/or phosphorylation of cortactin (12,14–16).

Another critical step in tumor cell invasion and metastasis is modulation of intercellular adhesion between cells in the primary tumor (17). The importance of classic cadherins and associated intercellular adherens junction components in tumor progression is widely appreciated (18,19). Although less well understood, a role for desmosomal cadherins and associated desmosome components has more recently emerged (20–26). Desmosomes are intercellular junctions that mediate strong cell-cell adhesion in tissues that suffer large amounts of mechanical strain, such as the epidermis and myocardium (26,27). They are composed of three main protein families: the desmosomal cadherins (desmogleins and desmocollins) and their associated armadillo family proteins (plakoglobin and plakophilins), which in turn are linked to plakin proteins (desmoplakin) (28,29). Mis-regulation of desmosomal cadherins or desmosomal armadillo family proteins has been associated with cell invasion and metastasis in different types of cancer (17,20–22,24,25,30–35). Moreover, desmosome loss can occur even before the disappearance of E-cadherin, consistent with this step being an important early event in the process of epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) contributing to cancer progression (20,30,36).

Desmoglein 1 (Dsg1) is a desmosomal cadherin that is first expressed as cells transit out of the basal proliferating layer of stratified epithelial tissues, and becomes more strongly concentrated in the superficial epithelial layers of the epidermis and oral cavity (26,27). While Dsg1’s roles in maintaining tissue integrity have been well-established, Dsg1 is also now known to be a key regulator of signaling pathways to modulate the balance of proliferation and differentiation. Through its cytoplasmic tail, Dsg1 inhibits both EGFR and the Erk/MAPK pathways (37,38). By interacting with the ErbB2 binding protein Erbin, Dsg1 inhibits the formation of Ras-Raf complexes upstream of Shoc2, leading to Erk1/2 signaling downregulation, which induces keratinocyte differentiation (37). In addition, Dsg1 is downregulated in different types of cancer that frequently overexpress EGFR, such as HNSCC. Reduced Dsg1 in these tumors correlates with a poorly differentiated phenotype and highly invasive carcinoma with low survival rate (39,40). Here, we demonstrate a role for Dsg1 in suppressing EGF-dependent invadopodia formation and function, and show that Dsg1’s ability to efficiently inhibit HNSCC cell invasion depends on its associated protein Erbin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and Drugs

Human-derived squamous cells carcinoma Cal33 cells and UMSCC1 squamous carcinoma cells, were cultured in DMEM/F-12 media supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and were used within five passages. For EGF stimulation experiments, Cal33, UMSCC1 cells and/or spheroids were serum starved in 0.5% FBS and 0.8% BSA in DMEM F-12 media for 16 h before stimulation with 50 ng/ml EGF. For experiments using inhibitors, Cal33 cells were serum starved for 16 h before treatment with DMSO (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5 μM EGFR inhibitor, AG1478 (Selleck Chemicals), or 5 μM Erk inhibitor, U0126 (Cell Signaling Technology).

Cell lines authentication

Cell lines obtained from the following sources were all subjected to short tandem repeat (STR) profiling to detect both contamination and misidentification, including intra- and inter- species contamination by IDEXX BioResearch (Columbia, MO): Cal33 (Sharon Stack, University of Notre Dame); SCC25 (Jennifer Grandis, University of Pittsburgh); SCC9 (J. Rheinwald, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA); SCC22B and UMSCC1 (Thomas Carey, University of Michigan); Cal27 cells were purchased from ATCC (CRL-2095). With one exception, lines had scores 80–100% indicating the samples are consistent with the cell line of origin. The SCC22B cell line had a score below 80% and due to uncertainty about its identity was not used beyond Supplemental Fig.1 in this study. Primary normal human epidermal keratinocyte isolates (NHEKs) are obtained through the Northwestern University Skin Disease Research Core, where mycoplasma, HIV-1, hepatitis B and C testing is routinely performed. Keratinocyte purity is assessed by immunostaining for epidermal keratinocyte specific markers, such as keratins K1/10 and K5/14. Mycoplasma is routinely performed for all lines using the Lonza MycoAlert mycoplasma detection kit and/or by real time PCR (IDEXX BioResearch, Columbia, MO).

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used: the cortactin antibody (ab33333) was from Abcam. The GAPDH (sc-365062) antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. The Tks5 (sc-30122) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. A second Tks5 antibody from EMD Millipore (MABT336) was used after sc-30122 became unavailable. The Dsg1 (AF944) antibody was from R&D Systems. The Erbin (22438–1-AP) antibody was from Proteintech. The EGFR (4267), pEGFR Y1068 (2234) and pErk1/2 (4370) antibodies were from Cell Signaling. The Erk1/2 (V114A) antibody was from Promega. The MT1-MMP (AB8345) and MMP-2 (AB809) antibodies were from Chemicon International. The ADAM 10 (CSA-835) antibody was from Stressgen Biotechnologies. The M2 Flag (F1804), Flag (F7425), and GAPDH (G9545) antibodies were from Sigma-Aldrich. The Dsg2 (610121) antibody was from Progen. The Dsg3 (MABT335) antibody was from Millipore. The E-cadherin (HECD1) antibody was a gift from M. Takeichi and O. Abe, RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, Kobe, Japan. The plakoglobin (1407) antibody was generated by Aves Laboratories. The K5 and K1 antibodies were a gift from J. Segre, National Human Genome Research Institute. Actin was visualized using phalloidin from Thermo Fisher (A22287).

Western blot analysis included use of peroxidase-conjugated anti- mouse, -rabbit, and -chicken secondary antibodies purchased from Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories. AlexaFluor 405/488/568/647-conjugated donkey anti- mouse, -goat, and -rabbit secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were used in immunofluorescence studies.

DNA constructs.

LZRS-Dsg1 full length Flag Tag, LZRS-mCherry, LZRS-Dsg1-ICS, LZRS-dPg, and LZRS-909 constructs were generated as previously described (37,38,41,42).

Retroviral Infections

The phoenix packaging cell line (provided by G. Nolan, Stanford University, Stanford California, USA), was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin and transfected with LZRS constructs (4 μg/ml) using Lipofectamine. Next day, cells were re-seeded into selection media with 1 μg/ml puromycin. When cells reached 70% confluency, they were switched to DMEM without puromycin and incubated at 32° C for 24 h. Viral supernatant was collected and concentrated using Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Units (Millipore). Cal33 cells were infected with virus and 8 μg/ml polybrene for 60–90 minutes at 32° C. Next, cells were washed with PBS and returned to growth at 37° C in complete DMEM/F-12 media.

siRNA treatment and transfection.

Cal33 and/or UMSCC1 cells at approximately 30–50% confluency were transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides at a final concentration of 20 nM via DharmaFECT. siRNA directed towards Erbin (Invitrogen Stealth siRNA: 5′-CCACACTGTTGTATGATCAACCATT-3′), Dsg2 (Dharmacon ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool, L-011645–00–0005: 5’-CAAUAUACCUGUAGUAGAA-3’, 5’-GAGAGGAUCUGUCCAAGAA-3’, 5’-GAGAGGAUCUGUCCAAGAA-3’, 5’-CCUUAGAGCUACGCAUUAA-3’, 5’-CCAGUGUUCUACCUAAAUA-3’) and scramble/non-targeting siRNA (Dharmacon, D-001206–14–20).

Invadopodial matrix degradation assay

The invadopodial matrix degradation assay was performed as previously described with minor modifications (9,11,43). Briefly, 75,000 cells were plated on 488-labeled gelatin overnight. The next day, cells were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, permeabilized in 0.1% Triton-X-100 for 30 min and stained with antibodies recognizing cortactin or actin, Tks5, and Dsg1. At least ten different fields were acquired per condition and each independent experiment was performed three times. Invadopodia were identified as Tks5 and cortactin positive punctate structures. Invadopodia were manually counted from images and reported as invadopodia per cell. Degradation area was determined by thresholding images and determining the number of dark pixels within punctate regions of degradation using the Analyze Particles command in ImageJ. The total degradation area in pixels was divided by the total number of cells sampled or by the average total cell area (in pixels) of the sampled cells to arrive at mean degradation area/cell or /cell area. The data was normalized to control (mCherry) by dividing each area of degradation by the mean degradation area of mCherry, setting the mean area of mCherry expressing cells to a value of 1.

Spheroid invasion assay

To generate spheroids, cells were plated at low density (0.5×104 cells/ml) into ultra-low attachment (ULA) 96-well round bottom plates as described (44). After 4 days of incubation, the spheroids were embedded in 100 μl of 5 mg/ml rat-tail collagen I (Corning Inc.). The collagen solution was prepared according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Alternate Gelation Procedure). EGF was added into each well when indicated. For the image analysis of spheroids, both the core and the distal margin of the invasion zone were manually outlined based on phase-contrast images using ImageJ. Then, the area of the core was subtracted to obtain the area of invasion.

Microscope imaging

For invadopodial matrix degradation assays, imaging was performed on a wide-field microscope (Upright Leica, model DMR) fitted with 40X (NA 1.0) oil immersion objective. Images were captured with an Orca 100 CCD camera (model C4742–95; Hammamatsu) and MetaMorph version 7.7.0 imaging software (Universal Imaging Corp.). For 3D invasion assays, spheroids were imaged using a phase-contrast inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss, Axiovert 40 CFL) fitted with 10X objective. Images were analyzed using ImageJ software (NIH version 1.6.0).

Western blot analysis

For analysis of protein expression levels, whole cell lysates were obtained by using urea-SDS buffer or RIPA buffer (for phosphoprotein analysis). Samples were run on 7.5% SDS-PAGE gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes to be probed with appropriate primary and secondary antibodies. Densitometric measurements of scanned immunoblots were performed using ImageJ.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Excel or GraphPad Prism software. P-values for two groups were calculated using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-tests. P-values for three or more groups were calculated using one-way ANOVA. P-values for multiple dependent variables were calculated using two-way ANOVA. Each group includes measurements from three independent experiments. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). All graphs are displayed as mean ± SEM.

RESULTS

Desmoglein 1 expression suppresses invadopodia formation and matrix degradation in HNSCC cells.

In light of our previous findings that Dsg1 suppresses EGFR/Erk signaling in keratinocytes (37,38), we hypothesized that Dsg1 may suppress HNSCC tumor invasion through its ability to interfere with EGF-dependent formation of invadopodia. To establish a model system for the study, we first evaluated a panel of oral SCC lines, including Cal33, Cal27, SCC25, SCC22B, SCC9, and UMSCC1, for expression of junction proteins, epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers, and ability to degrade gelatin. All cell lines tested had lost expression of Dsg1 (Supplemental Fig. 1). Cal27, SCC25, SCC22B and SCC9 cells were excluded from the study as they had already progressed to express EMT markers such as N-cadherin, vimentin or both. Cal33 and UMSCC1 retained expression of junctional proteins such as E-cadherin without having begun to express EMT markers. Therefore, we selected these lines for further evaluation of Dsg1’s role in invadopodia formation and function.

While Cal33 cells have lost expression of Dsg1, they still express the desmoglein isoforms, Dsg2 and Dsg3 (Supplemental Fig. 2), and the classic cadherin adhesion machinery, including E-cadherin and associated catenins (Fig. 1A). This selective loss of Dsg1 suggests that Cal33 have progressed to a more tumorigenic phenotype, but still retain their baseline adhesion machinery. Towards addressing whether exogenous Dsg1 can suppress invadopodia formation, Cal33 cells were transduced with LZRS Dsg1 full length Flag-tag (Dsg1FL). mCherry was used as a control. Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates confirmed the efficacy of the transduction (Fig. 1A).

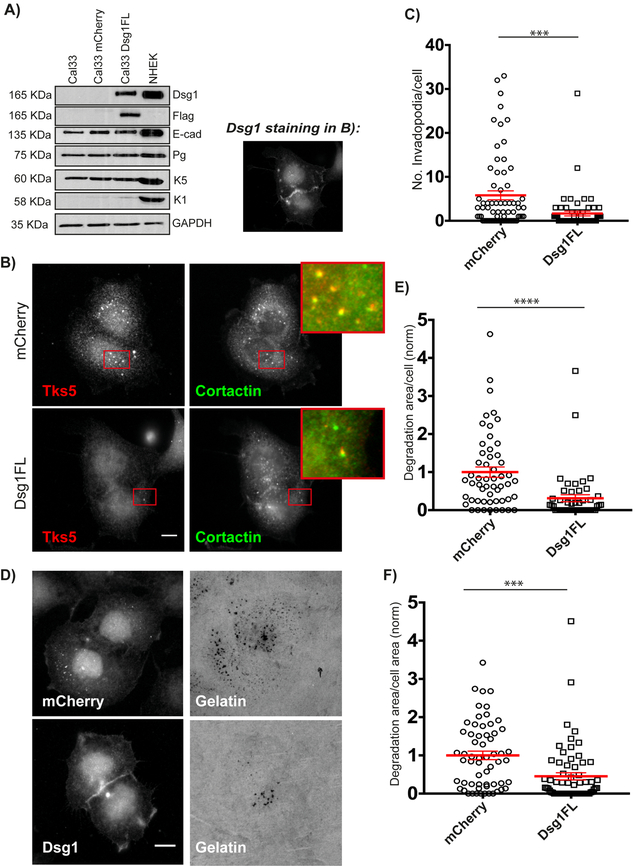

Figure 1. Desmoglein 1 regulates invadopodia formation and function.

A) Western blot of whole cell lysates from Cal33, Cal33-mCherry, Cal33-Dsg1FL and NHEK cells probed for Dsg1, Flag, E-cadherin (E-cad), Plakoglobin (Pg), Keratin 5 (K5), Keratin 1 (K1), and GAPDH (NHEK was used for comparison). B) Cal33-mCherry and Cal33-Dsg1FL cells stained for invadopodia markers, Tks5 and cortactin. Inset shows magnified image of invadopodia in red box. Smaller image shows Dsg1 staining in Dsg1FL cells. C) Quantification of the number of invadopodia per cell. n>400 invadopodia from >100 cells; three independent experiments. Unpaired student’s t-test with Welch’s correction. ***p=0.0005. Error bars indicate SEM. D) Cal33-mCherry and Cal33-Dsg1FL cells after overnight plating on 488-labeled gelatin. E) Quantification of invadopodial matrix degradation area per cell normalized to control. Normalization of data was done by dividing each area of degradation by the mean degradation area of mCherry expressing cells. n>100 cells; three independent experiments. Unpaired student’s t-test with Welch’s correction. ****p<0.0001. Error bars indicate SEM. F) Quantification of degradation area per cell area normalized to mCherry expressing cells. n>100 cells; three independent experiments. Unpaired student’s t-test with Welch’s correction. ***p=0.0003. Error bars indicate SEM. Scale bars equal 10 μm.

Next, Cal33-mCherry and Cal33-Dsg1FL cells were assayed for invadopodium formation. Cells were plated on 488-gelatin overnight, then fixed and stained for Tks5 and cortactin as invadopodia markers. Dsg1FL cells were also stained for Dsg1, and only those cells expressing Dsg1 at cell-cell interfaces were counted for the assay. Invadopodia were identified as Tks5 and cortactin positive punctate structures and reported as invadopodia per cell. Imaging analysis showed that upon Dsg1 expression the number of invadopodia decreased by 75% (Fig. 1B and C). It should be noted that whereas the basal keratin K5 is present regardless of Dsg1 expression status, exogenous expression of Dsg1 in Cal33 cells does not induce the expression of differentiation markers such as K1 (Fig. 1A). This finding is consistent with the idea that Dsg1’s ability to interfere with invadopodia formation is not an indirect effect of promoting differentiation.

Since the primary function of invadopodia is to degrade basement membranes through secretion of MMPs, we analyzed the ability of the cells to degrade the underlying gelatin. Degradation area was calculated as the total area covered by degradation holes/cell in thresholded images using the Analyze Particles command in ImageJ. Expression of Dsg1FL resulted in a decrease in the degradation area per cell (Fig. 1D and E) and degradation area per cell area (Fig. 1F) by 68% and 54% respectively. This is most likely due to a decrease in the number of invadopodia, rather than a decrease in MMP secretion, since quantification of the degradation area per invadopodium showed no differences between control and Dsg1FL cells (Supplemental Fig. 3). Additionally, the expression levels of MT1-MMP, ADAM10 and MMP-2, the major proteinases secreted by invadopodia, remained unchanged upon Dsg1 expression (Supplemental Fig. 4), suggesting that invadopodia formed in both types of cells are equally active.

EGFR stimulation does not increase the number of invadopodia or invasion of Cal33-desmoglein 1 expressing cells.

Invadopodia formation is a multistep process that starts with the formation of a precursor, which is a structure constituted by all the proteins that form the invadopodium core, but has not yet acquired the capacity to degrade the ECM. Subsequent precursor maturation then results in full proteolytic activity (8). It is well known that invadopodia can form through activation of EGFR by EGF or other stimuli (e.g. TGF-β or PDGF) in different types of cancer cells (7,45). As we previously showed that Dsg1 attenuates EGFR activity and downstream MAPK signaling in an adhesion-independent manner (37,38), we tested whether Dsg1 regulates the early stages of invadopodium precursor formation.

To test this hypothesis, Cal33-mCherry and Cal33-Dsg1FL cells were serum starved overnight and stimulated with 50 ng/ml EGF for 0 minutes (untreated) and 3 minutes to synchronously induce precursor formation. Whereas the number of invadopodia increased 4.5-fold in response to EGF treatment in mCherry cells, Dsg1FL-expressing cells failed to exhibit an increase in the number of invadopodia precursors upon EGF stimulation (Fig. 2A and B).

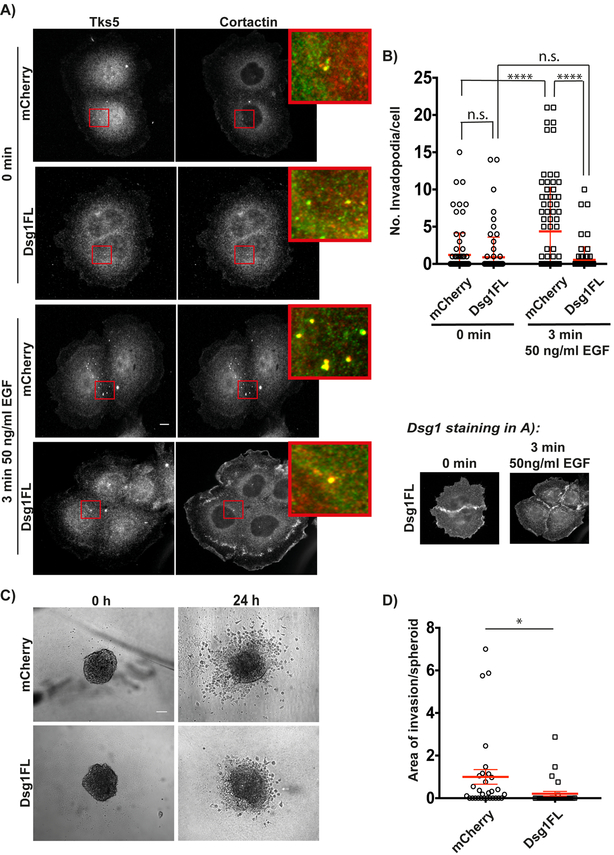

Figure 2. Desmoglein 1 suppresses EGF-induced invadopodium precursors and 3D invasion.

A) Cal33-mCherry and Cal33-Dsg1FL cells stained for invadopodia markers Tks5 and cortactin at 0 minutes (untreated) and 3 minutes after 50 ng/ml EGF stimulation. Inset shows magnified image of invadopodia in red box. B) Quantification of the number of invadopodia per cell at 0 minutes (untreated) and 3 minutes after EGF stimulation. n>500 invadopodia from >250 cells; three independent experiments. Two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparison test. ****p<0.0001. Error bars indicate SEM. C) Phase-contrast images of invasion of Cal33-mCherry and Cal33-Dsg1FL spheroids embedded in rat tail collagen type I (5 mg/ml) at 0 h (untreated) and 24 h after EGF stimulation. D) Quantification of area of invasion per spheroid normalized to control at 24 h after EGF stimulation. n=30 spheroids; three independent experiments. Unpaired Student’s test with Welch’s correction. *p=0.034. Error bars indicate SEM. Scale bars equal 10 μm.

To determine whether Dsg1 is also capable of suppressing invadopodia in a more physiologically relevant 3D environment, we carried out invasion assays using spheroids in which tumor cells are organized into a 3D structure mimicking a tumor micro-region. Spheroids are embedded into rat-tail collagen 1, where MMP activity is required to invade out of the tumor mass into the surrounding matrix (46,47). At 0 h (no stimulation), there are no obvious differences in size and morphology between the spheroids from Cal33-mCherry and Cal33-Dsg1FL cells (Fig. 2C). However, after 24 h of EGF stimulation Dsg1FL-expressing spheroids fail to invade into the collagen, showing a reduction in the invasion area by 80% when compared with spheroids from control cells (Fig. 2C and D). Overall, these results suggest that Dsg1 expression inhibits the early stages of EGF-induced invadopodium precursor formation leading to a decrease in the invasion capacity.

The Erbin binding region on Desmoglein 1 is required to suppress invadopodia formation and function.

In addition to the shared intracellular cadherin-typical sequence (ICS) required for Pg binding, the cytoplasmic tail of the Dsg isoforms contain unique C-terminal domains not found in other desmosomal or classical cadherins. These include an intracellular proline-rich linker (PL), a variable number of repeating unit domains (RUD), and a glycine-rich desmoglein-specific terminal domain (TD) (29,48) (Fig. 3A). To address which Dsg1 domains are important for suppressing invadopodia formation, we tested several previously published Dsg1 mutants in Cal33 cells (37,38,41,42). These include Dsg1-dPg, a triple-point mutant of the catenin-like region, which interferes with plakoglobin binding; Dsg1–909 mutant that lacks the last 140 aa on Dsg1 cytoplasmic tail; and Dsg1-ICS mutant that lacks the PL, RUD, and TD domains, and is unable to bind Erbin (Dsg1-ICS) (Fig. 3A and B). We previously showed that through its association with Erbin, Dsg1 suppresses Erk1/2 activation downstream of EGFR by inhibiting the Ras-Raf scaffolds mediated by Shoc2 (37).

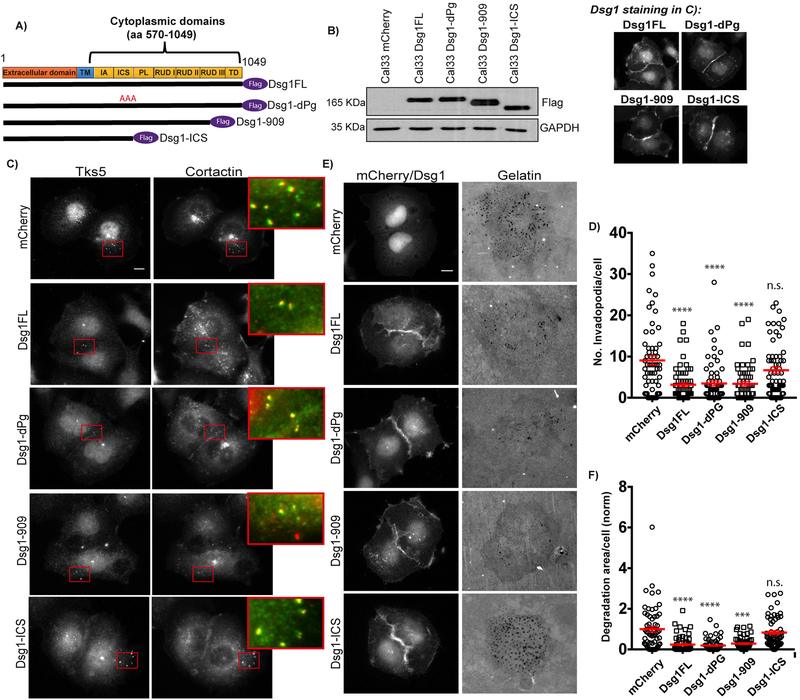

Figure 3. Erbin binding domain of Desmoglein 1 is required to regulate invadopodia.

A) Schematic of Dsg1 constructs. B) Western blot of whole cell lysates from Cal33-mCherry, -Dsg1FL, -Dsg1-dPg, -Dsg1–909, and -Dsg1-ICS probed for Flag and GAPDH. C) Cal33-mCherry, -Dsg1FL, -Dsg1-dPg, -Dsg1–909, and -Dsg1-ICS cells stained for invadopodia markers, Tks5 and cortactin. Inset shows magnified image of invadopodia in red box. Smaller images show Dsg1 staining in Dsg1 constructs. D) Quantification of the number of invadopodia per cell. n>1600 invadopodia from n>300 cells; three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Dunn’s post hoc test. ****p<0.0001. Error bars indicate SEM. E) Cal33-mCherry, -Dsg1FL, -Dsg1-dPg, -Dsg1–909, and -Dsg1-ICS cells after overnight plating on 488-labeled gelatin. F) Quantification of invadopodial matrix degradation area per cell normalized to control. n>300 cells; three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Dunn’s post-hoc test. ****p<0.0001 and ***p=0.0002. Error bars indicate SEM. Scale bars equal 10 μm.

Next, we assayed all the mutants for invadopodia formation after overnight plating on fluorescent gelatin, and found that the number of invadopodia formed by Cal33 Dsg1-dPg and Dsg1–909 were suppressed to the same level as Cal33-Dsg1FL cells. Conversely, cells expressing the Dsg1-ICS mutant failed to suppress invadopodia, exhibiting a similar number as control cells (Fig. 3C and D). Consistent with these results, quantification of the degradation area per cell decreased compared with control, and showed no differences between Dsg1-FL, Dsg1-dPg and Dsg1–909. In contrast, Dsg1-ICS mutant failed to suppress degradation (Fig. 3E and F).

Collectively, these results show that the Dsg1 domain known to be required for Erbin binding is necessary to regulate invadopodia formation and function.

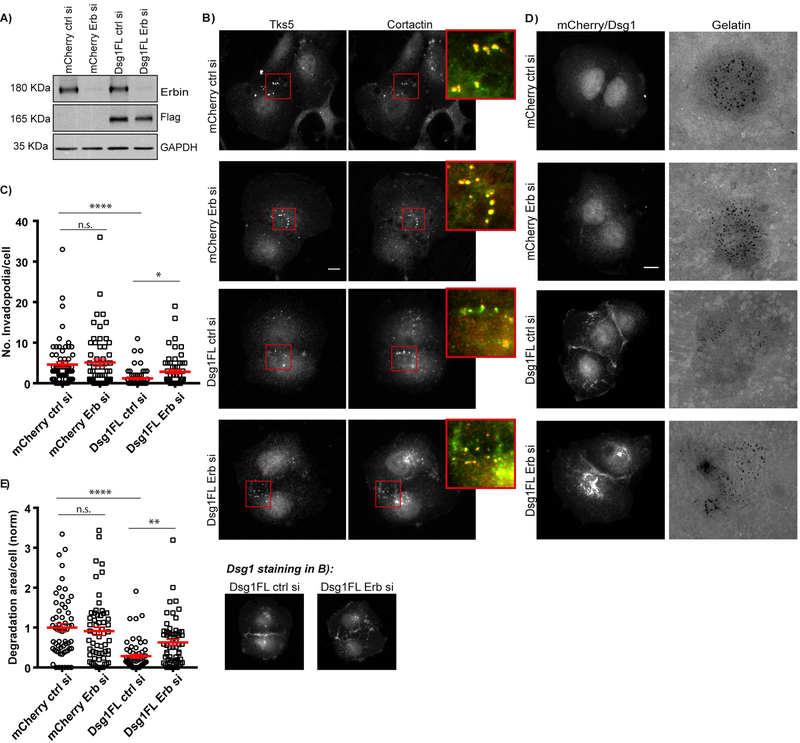

Efficient suppression of invadopodia by Desmoglein 1 is Erbin-dependent

Since the Dsg1-ICS mutant lacks several domains on Dsg1 tail that could be affecting other unknown binding partners, to more directly address Dsg1’s dependence on Erbin to suppress invadopodia, we next silenced Erbin in Cal33 cells in the presence and absence of Dsg1 expression (Fig. 4A). Introducing Dsg1 along with a control siRNA resulted in a 73% reduction in the number of invadopodia, similar to that shown above. However, in cells expressing Dsg1 in the presence of Erbin knockdown the reduction in the number of invadopodia was only 37% when compared to control cells, suggesting that Dsg1 depends at least in part on Erbin for its invadopodia-suppressing function (Fig. 4B and C). Importantly, Erbin knockdown alone did not affect the number of invadopodia compared with control cells, suggesting that its role in regulating invadopodia formation requires the presence of Dsg1 (Fig. 4B and C). Similar results were obtained when analyzing matrix degradation per cell. Dsg1 in the presence of control siRNA suppresses matrix degradation, but its ability to do so is impaired upon Erbin depletion. Depletion of Erbin alone, however, did not have any effect on matrix degradation compared with control (Fig. 4D and E). These observations are consistent with the idea that Erbin acts in a complex with Dsg1 to inhibit invadopodia formation and matrix degradation.

Figure 4. Desmoglein 1 mediates invadopodia formation and function through Erbin.

A) Cal33-mCherry and Cal33-Dsg1 FL cells were transfected with control or Erbin siRNA and whole cells lysates were immunoblotted after 72 h of transfection with Erbin, Flag and GAPDH antibodies. B) Cal33-mCherry and Cal33-Dsg1FL cells treated with control or Erbin siRNA and stained for invadopodia markers, Tks5 and cortactin. Inset shows magnified image of invadopodia in red box. Smaller images show Dsg1 staining in Dsg1 expressing cells. C) Quantification of the number of invadopodia per cell. n>800 invadopodia from n>200 cells; three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Dunns’s multiple comparisons test. ****p<0.0001 and *p=0.0319. Error bars indicate SEM. D) Cal33-mCherry and Cal33-Dsg1FL cells treated with control or Erbin siRNA and plated on 488-labeled gelatin overnight. E) Quantification of invadopodial matrix degradation per cell normalized to control. n>200 cells; three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA with Dunns’s multiple comparison test. ****p<0.0001 and **p<0.01. Error bars indicate SEM. Scale bars equal 10 μm.

We next examined whether Erbin was required for Dsg1-dependent inhibition of invadopodia following EGF stimulation. Dsg1FL expressing cells did not increase invadopodia formation in response to EGF stimulation. Erbin depletion in Dsg1 expressing cells exhibited a 1.7-fold increase in invadopodia formation upon EGF stimulation compared to the unstimulated control (Supplemental Fig. 5) (p=0.078 trending toward significance).

In order to demonstrate the impact of the Dsg1-Erbin complex on invadopodia formation is not cell type specific, we expressed Dsg1 in the HNSCC line UMSCC1. Both invadopodia formation and matrix degradation were also reduced in this cell type in the presence of Dsg1 (72% and 82% respectively compared to mCherry controls), in an Erbin-dependent fashion (Supplemental Fig. 6).

It has been reported that activation of EGFR and Erk are required to initiate the pathways that lead to actin polymerization and ultimately matrix degradation (15,45). Since we previously showed that Dsg1-Erbin interaction attenuates EGFR/Erk signaling (37,38), we measured their activation levels in Cal33 cells expressing Dsg1 in the presence and absence of Erbin. Western blot analysis showed that in control cells, Erbin depletion has no effect in the phosphorylation state of EGFR and Erk1/2 (Fig. 5A). In Dsg1FL cells treated with control siRNA, activation of EGFR and Erk1/2 was suppressed as previously reported for normal epidermal keratinocytes (37,38). However, Dsg1FL was unable to suppress EGFR and Erk1/2 in cells that were also transfected with Erbin RNAi (Fig. 5A). Together, these results suggest that Dsg1 requires Erbin to efficiently downregulate EGFR/Erk1/2 signaling in Cal33 HNSCC cells, comparable to normal epidermal keratinocytes.

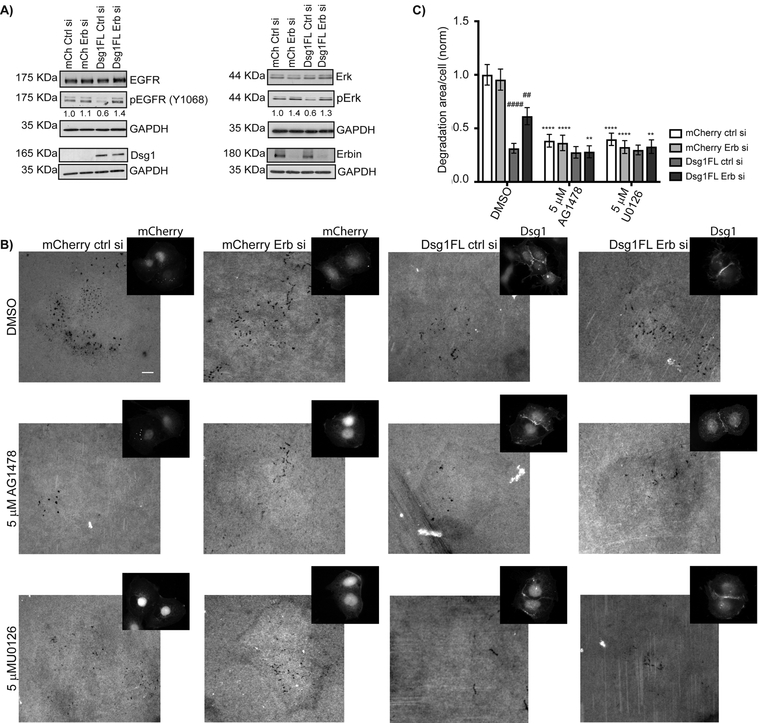

Figure 5. Desmoglein 1 attenuates invadopodia signaling in an Erbin-dependent manner.

A) Cal33-mCherry and Cal33-Dsg1FL cells were transfected with control or Erbin siRNA and whole cells lysates were immunoblotted after 72 h of transfection with EGFR, pEGFR (Y1068), Erk, pErk (p44/42), Erbin, Flag, and GAPDH antibodies. For quantification of phosphorylated proteins, each band was normalized to the amount of total protein. Three independent experiments. B) Cal33-mCherry and Cal33-Dsg1FL cells treated with control or Erbin siRNA plus vehicle (DMSO), EGFR (5 μM AG1478), and Erk (5 μM U0126) inhibitors and plated on 488-labeled gelatin for 6 h. Smaller images show mCherry IF and Dsg1 staining. Scale bars equal 10 μm. C) Quantification of invadopodial matrix degradation per cell. n>700 cells; three independent experiments. Two-way ANOVA with Dunn’s post-hoc test. Analysis within groups reveals that only DMSO treatment show significant decreases in Dsg1FL ctrl si and Dsg1FL Erb si as compared to mCherry ctrl si. ####p<0.0001 and ##p=0.032. Analysis across groups reveals significant decreases in degradation area/cell following AG1478 and U0126 drug treatment under all expression conditions except Dsg1FL ctrl si.****p<0.0001 and **p=0.0073. Error bars indicate SEM.

We next took a pharmacological approach to address the extent to which the observed difference in matrix degradation between Dsg1-expressing cells and Erbin-deficient Dsg1 expressing cells is EGFR or Erk1/2-dependent. We first silenced Erbin in Cal33 cells in the absence and presence of Dsg1 expression. Next, to initiate invadopodia formation, cells were cultured in complete media for 6 hours and treated with the vehicle DMSO as a control, EGFR inhibitor (5 μM AG1478) or Erk inhibitor (5 μM U0126).

Consistent with previous experiments, Dsg1FL-ctrl siRNA cells treated with DMSO suppressed matrix degradation by 67% when compared to control cells (Fig. 5B–C). Erbin depletion reduced Dsg1’s effectiveness; under these conditions matrix degradation was suppressed by 37% when compared to control cells (Fig. 5B–C). Erbin knockdown in control cells did not show any effect (Fig. 5B–C). EGFR or Erk inhibitors reduced matrix degradation in mCherry (control) cells 60% compared to DMSO-treated cells, as expected from previous reports (15,49). EGFR or Erk inhibitors reduced matrix degradation in Dsg1-Erbin siRNA cells and mCherry cells with and without Erbin, to levels similar to those observed in Dsg1FL-ctl siRNA-treated cells (Fig. 5B–C). No further reduction in matrix degradation occurred in Dsg1FL expressing cells treated with the inhibitors. This is consistent with the idea that Dsg1, in the presence of Erbin, is just as powerful as the pharmacological inhibitors of EGFR/Erk to suppress these downstream effectors and associated matrix degradation when re-introduced into cells that have lost Dsg1 expression. These data also reveal an Erbin-independent component of Dsg1 invadopodia inhibition in addition to the EGFR/Erk-dependent component in the Dsg1 siErbin cells.

To determine whether loss of Dsg1 is associated with progression of HNSCC in vivo, we used the TCGA database (50) to compare Dsg1 mRNA expression levels in tumors with histologic grades 1–4. Significant reductions in Dsg1 mRNA occur at each stage from 1–3 (Supplemental Fig. 7A). While Dsg1 in stage 4 tumors was not further reduced compared with stage 3, a relatively low number of samples was in the database for stage 4.

Interestingly, Dsg2, which was previously shown to be elevated in malignant skin carcinoma (51) and to predispose transgenic animals in which it is mis-expressed to SCC development (52), was elevated in expression from stage 1–3 (50) (Supplemental Fig. 7A). To determine whether Dsg2 has an impact on invadopodia formation we carried out Dsg2 knockdown experiments in Cal33 cells, which express this basal desmoglein endogenously. Notably, knockdown of Dsg2 suppressed both invadopodia formation and degradation in these cells, indicating it has a reciprocal role to Dsg1 in regulating invadopodia (Supplemental Fig. 7B–E).

DISCUSSION

EGFR is overexpressed in >90% of HNSCC patients, and its expression correlates with enhanced invasion and metastasis (3,4). We previously showed that Dsg1 dampens EGFR/Erk signaling (37,38), and downstream effectors of EGFR are known to promote formation of invadopodia protrusions to facilitate cancer cell invasion and metastasis (7,45).Therefore, we asked whether Dsg1 serves as an invasion suppressor through its ability to regulate EGFR signaling. We demonstrate for the first time that expression of Dsg1 in oral cancer cells is sufficient to suppress invadopodia formation and invasion in 2D and 3D assays. The potential in vivo relevance of this finding is supported by analysis of TCGA data from staged HNSCC tumors, showing progressive loss of Dsg1 mRNA expression with increased histological grade (50) (Supplemental Fig. 7A). This analysis supports previous smaller studies associating Dsg1 loss with increased metastasis and poor patient outcome in HNSCC (39,40).

One prominent feature of most cancer cells is that they fail to differentiate normally (53), however, exogenous expression of Dsg1 in HNSCC cells does not induce the expression of differentiation markers, such as K1, suggesting that the mechanism by which Dsg1 is suppressing invasion is independent from the differentiation process.

Dsg1’s role in suppressing EGFR is in contrast to that of the desmosomal cadherin, Dsg2, which promotes growth factor signaling pathways when over-expressed in the basal layer of mouse epidermis (52) and increases cell growth and migration in an EGFR-dependent manner in vitro (21,22). Here we show that Dsg2 acts in a reciprocal fashion to Dsg1 by promoting invadopodia formation and matrix degradation in HNSCC cells (Supplemental Fig. 7B–D). In addition, analysis of TCGA data show that Dsg2 expression increases, rather than decreases, with HNSCC histological grade (50) (Supplemental Fig. 7A). Dsg2’s role in promoting EGFR signaling may be more broadly important in cancer, as it was also observed that Dsg2 downregulation inhibited EGFR signaling and cell proliferation through downstream Erk activation in colon cancer cells (23). These data are consistent with the idea that Dsg2 promotes, whereas Dsg1 inhibits, growth factor signaling to maintain a balance of proliferation and differentiation in complex tissues. In addition, the work suggests that re-introducing Dsg1 into HNSCC cells is sufficient to overcome any pro-invasive signaling that may be occurring through endogenous Dsg2 in HNSCC. Similarly, the presence of Dsg1 may also counter signaling through Dsg3, a basal keratinocyte desmoglein that promotes cell migration and invasion by controlling cortical regulators of the actin cytoskeleton and is up-regulated in SCC (24,36).

Desmoglein armadillo proteins including plakoglobin and plakophilins (1–3) also have an impact on cancer progression. Like Dsg1, plakophilin 1 is downregulated in cancer (30,31), and it has been shown that its expression suppresses cell migration and invasion in HNSCC cells (30). Conversely, plakophilin 2 and 3 promote neoplastic progression in different types of cancers where their expression is frequently up-regulated (32,34,35). The expression of all three plakophilins in Cal33 cells suggest that Dsg1, alone or together with plakophilin 1, is enough to suppress any potential pro-invasive effects exerted by plakophilin 2 and 3.

In our study, a Dsg1 mutant with a 95% decreased ability to binding to plakoglobin was still able to suppress invadopodia formation and function. Thus, it seems likely that the remaining Dsg domains are sufficient to exert control over cell growth or migration mediated by plakoglobin in this setting. These considerations also suggest that our previous demonstration that plakoglobin suppresses keratinocyte migration through Src- and FN-dependent mechanisms cannot explain Dsg1’s control over HNSCC cell invasion (54,55).

We previously showed that Dsg1 interacts with the ErbB2 Interacting Protein, Erbin, to suppress MAPK/Erk signaling and support normal keratinocyte differentiation (37). Erbin localizes at the basolateral membrane to regulate cell junctions and polarity in epithelial cells (56,57). However, the role of Erbin during cancer progression varies depending on context. It has been reported that Erbin can act as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting TGFβ and Erk1/2 signaling (58–60). In HeLa cells, Erbin depletion causes an increase in cell proliferation and migration (61). Conversely, Erbin can also promote tumorigenesis and tumor growth in colorectal cancer cells by interacting with c-Cbl and preventing ubiquitination of EGFR (62).

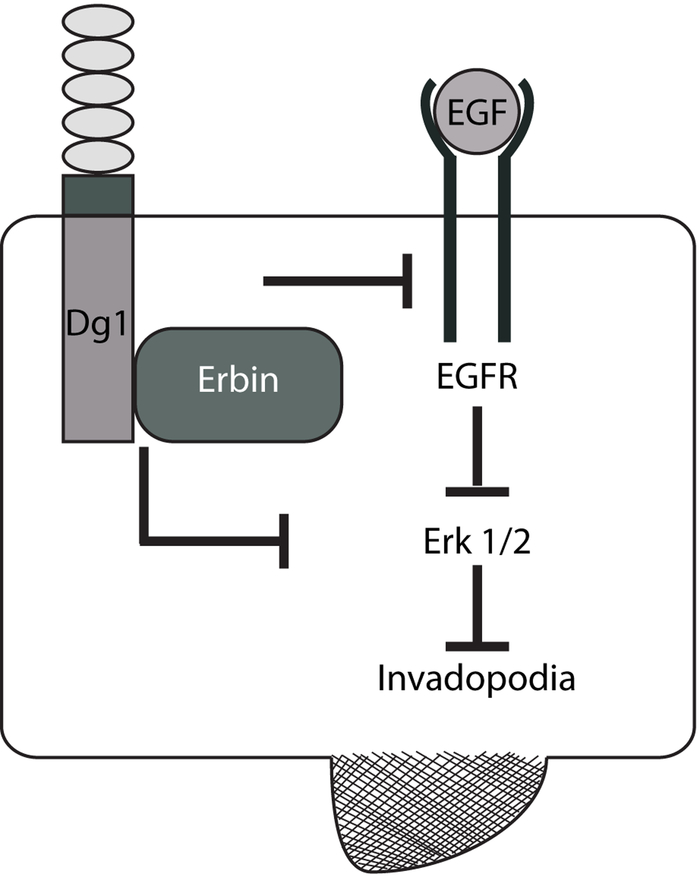

In our study, we showed that Erbin knockdown in the absence of Dsg1 has no effect on the number of invadopodia and matrix degradation. However, Erbin knockdown impairs Dsg1’s ability to efficiently suppress invadopodia and matrix degradation to the same level as Dsg1FL-expressing cells transfected with control siRNA. The same phenotype is observed when a Dsg1 mutant that cannot bind to Erbin is expressed (Dsg1-ICS). Furthermore, invadopodia signaling is downregulated when Dsg1 and Erbin are both present. When Erbin is depleted, Dsg1 by itself can no longer efficiently suppress EGFR/Erk signaling or invadopodia-mediated matrix degradation. Addition of pharmacological inhibitors of EGFR or Erk1/2, reduce levels of degradation in Erbin-depleted cells to that observed in Dsg1 cells expressing Erbin. These data indicate the importance of Erbin in suppressing these downstream effectors of invadopodia and matrix degradation. Collectively, our data suggest that re-introducing Dsg1 into HNSCC cells that have lost Dsg1 expression inhibits invadopodia formation and function in an Erbin-dependent manner by attenuating EGFR/Erk signaling (Fig. 6). Because Erbin alone is not sufficient to mediate these effects, these data are consistent with the idea that Dsg1 positions Erbin in proximity to the EGFR/Erk1/2 machinery to dampen invadopodia-promoting signals and/or to promote invadopodia inhibitory signaling.

Figure 6. Model:

Dsg1 through its interaction with Erbin downregulates invadopodia signaling by dampening EGFR/Erk activation, which ultimately leads to a decrease in invadopodia formation and matrix degradation.

In addition to the Erbin-dependent ability to suppress EGFR/Erk1/2-mediated matrix degradation in the presence of Dsg1, Dsg1 exhibited an Erbin-independent component to its suppressive ability (e.g. Fig. 5B, C). In this case suppression occurs through a mechanism independent of EGFR/Erk status, possibly through other binding partners of the Dsg1 downstream of the conserved ICS domain (Fig. 3A). These data provide new insight into how Dsg1 may function as an invasion suppressor in HNSCC, and opens up possible new targets for development of strategies for interfering with head and neck cancer progression.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Jennifer L. Koetsier for optimization of experiments, Bethany Perez-White for her helpful advice on the spheroid invasion assay, and all the members on the Green laboratory for insightful discussions during development of this project.

Gifts were provided by Sharon Stack (Cal33 cell line), Jennifer Grandis (SCC25 cell line), J. Rheinwald (SCC9 cell line), Thomas Carey (SCC22B and UMSCC1 cell lines), M. Takeichi and O. Abe (E-cadherin antibody), Julie Segre (K5 and K1 antibodies), G. Nolan (Phoenix package cell line). NHEK cells were obtained from the Keratinocyte Core of the Northwestern University Skin Disease Research Center.

GRANT SUPPORT

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 CA122151, R01 AR041836 and R37 AR043380 with partial support from the J.L. Mayberry Endowment to Kathleen J. Green.

Alejandra Valenzuela-Iglesias was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship Grant by the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, CONACYT. Mexico.

Abbreviation list:

- Dsg1

Desmoglein 1

- HNSCC

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas

- Erbin

ErbB2 Interacting Protein

- EGFR

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- MMPs

Matrix metalloproteinases

Footnotes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Marur S, and Forastiere AA. Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Update on Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Mayo Clin. Proc 2016; 91, 386–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curry JM, Sprandio J, Cognetti D, Luginbuhl A, Bar-ad V, Pribitkin E, et al. Tumor Microenvironment in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Semin. Oncol 2014; 41, 217–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Echarri JM, Lopez-Martin A, and Hitt R. Targeted Therapy in Locally Advanced and Recurrent/Metastatic Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (LA-R/M HNSCC). Cancers 2016; 8, 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sacco AG, and Worden FP. Molecularly targeted therapy for the treatment of head and neck cancer: a review of the ErbB family inhibitors. OncoTargets. Ther 2016; 9, 1927–1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartmann S, Bhola NE, and Grandis JR. HGF / Met Signaling in Head and Neck Cancer: Impact on the Tumor Microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2016: 22, 4005–4013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boeckx C, Baay M, Wouters A, Specenier P, Vermorken JB, Peeters M, et al. Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Therapy in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Focus on Potential Molecular Mechanisms of Drug Resistance. Oncologist 2013; 18, 850–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaty BT, and Condeelis J. Digging a little deeper: the stages of invadopodium formation and maturation. Eur J Cell Biol. 2014; 93, 438–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oser M, Eddy R, and Condeelis J. Actin-based Motile Processes in Tumor Cell Invasion In Carlier MF. (eds) Actin-based Motility. Springer, Dordrecht: 2010. p. 125–164. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Valenzuela-Iglesias A, Sharma VP, Beaty BT, Ding Z, Gutiérrez-Millán LE, Roy P, et al. Profilin1 regulates invadopodium maturation in human breast cancer cells. Eur. J. Cell Biol 2015; 94, 78–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beaty BT, Sharma VP, Bravo-Cordero JJ, Simpson MA, Eddy RJ, Koleske AJ, et al. β1 integrin regulates Arg to promote invadopodial maturation and matrix degradation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013; 24, 1661–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beaty BT, Wang Y, Bravo-Cordero JJ, Sharma VP, Miskolci V, Hodgson L, et al. Talin regulates moesin-NHE-1 recruitment to invadopodia and promotes mammary tumor metastasis. J. Cell Biol 2014; 205, 737–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eddy RJ, Weidmann MD, Sharma VP, and Condeelis JS. Tumor Cell Invadopodia: Invasive Protrusions that Orchestrate Metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2017; 8, 595–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bravo-Cordero JJ, Hodgson L, and Condeelis J. Directed cell invasion and migration during metastasis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol 2012; 24, 277–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hayes KE, Walk EL, Ammer AG, Kelley LC, Martin KH, and Weed S. Ableson Kinases Negatively Regulate Invadopodia Function and Invasion in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Inhibiting an HB-EGF Autocrine Loop. Oncogene 2013; 32, 4766–4777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayala I, Baldassarre M, Giacchetti G, Caldieri G, Tetè S, Luini A, et al. Multiple regulatory inputs converge on cortactin to control invadopodia biogenesis and extracellular matrix degradation. J. Cell Sci 2008; 121, 369–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang YS, Park KK, and Chung WY. Invadopodia formation in oral squamous cell carcinoma: The role of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Arch. Oral Biol 2012; 57, 335–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huber O, and Petersen I. 150th Anniversary Series: Desmosomes and the Hallmarks of Cancer. Cell Commun. Adhes 2015; 22, 15–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez FJ, Lewis-Tuffin LJ, and Anastasiadis PZ. E-cadherin’s dark side: possible role in tumor progression. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012; 1826, 23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajwar YC, Jain N, Bhatia G, Sikka N, Garg B, and Walia E. Expression and Significance of Cadherins and Its Subtypes in Development and Progression of Oral Cancers: A Review. J. Clin. Diagnostic Res 2015; 9, 5–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dusek RL, and Attardi LD. Desmosomes: new perpetrators in tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2011; 11, 317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Overmiller AM, Pierluissi JA, Wermuth PJ, Sauma S, Martinez-Outschoorn U, Tuluc M, et al. Desmoglein 2 modulates extracellular vesicle release from squamous cell carcinoma keratinocytes. FASEB 2017; 31, 3412–3424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Overmiller AM, McGuinn KP, Roberts BJ, Cooper F, Brennan-Crispi DM, Deguchi T, et al. c-Src / Cav1-dependent activation of the EGFR by Dsg2. Oncotarget 2016; 7, 37536–37555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamekura R, Kolegraff KN, Nava P, Hilgarth RS, Feng M, Parkos CA, et al. Loss of the desmosomal cadherin desmoglein-2 suppresses colon cancer cell proliferation through EGFR signaling. Oncogene 2014; 33, 4531–4536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown L, Waseem A, Cruz IN, Szary J, Gunic E, Mannan T, et al. Desmoglein 3 promotes cancer cell migration and invasion by regulating activator protein 1 and protein kinase C-dependent-Ezrin activation. Oncogene 2014; 33, 2363–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chidgey M, and Dawson C. Desmosomes: a role in cancer? Br. J. Cancer 2007; 96, 1783–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Broussard JA, Getsios S. and Green KJ. Desmosome regulation and signaling in disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2015; 501–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson JL, Najor NA, and Green KJ. Desmosomes: Regulators of Cellular Signaling and Adhesion in Epidermal Health and Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014; 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kowalczyk A, and Green K. Structure, Function and Regulation of Desmosomes. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2013; 116, 95–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nekrasova O, and Green K. Desmosome assembly and dynamics. Trends Cell Biol 2013; 23, 537–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobolik-Delmaire T, Katafiasz D, Keim SA, Mahoney MG, and Wahl III JK. Decreased Plakophilin-1 Expression Promotes Increased Motility in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells. Cell Commun. Adhes 2007; 14, 99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang C, Fischer-Keso R, Schlechter T, Strobel P, Marx A, and Hofmann I. Plakophilin 1-deficient cells upregulate SPOCK1: implications for prostate cancer progression. Tumor Biol. 2015; 36, 9567–9577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arimoto KI, Burkart C, Yan M, Ran D, Weng S, and Zhang DE. Plakophilin-2 Promotes Tumor Development by Enhancing Ligand- Dependent and -Independent Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Dimerization and Activation. Mol. Cell. Biol 2014; 34, 3843–3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khapare N, Kundu ST, Sehgal L, Sawant M, Priya R, Gosavi P, et al. Plakophilin3 Loss Leads to an Increase in PRL3 Levels Promoting K8 Dephosphorylation, Which Is Required for Transformation and Metastasis. PLoS One 2012; 7, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demirag GG, Sullu Y, and Yucel I. Expression of Plakophilins (PKP1, PKP2, and PKP3) in breast cancers. Med Oncol 2012; 29, 1518–1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breuninger S, Reidenbach S, Sauer CG, Strobel P, Pfitzenmaier J, et al. Desmosomal Plakophilins in the Prostate and Prostatic Adenocarcinomas Implications for Diagnosis and Tumor Progression. Am. J. Pathol 2010; 176, 2509–2519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown L, and Wan H. Desmoglein 3: A Help or a Hindrance in Cancer Progression. Cancers 2015; 7, 266–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harmon RM, Simpson CL, Johnson JL, Koetsier JL, Dubash AD, Najor NA, et al. Desmoglein-1/Erbin interaction suppresses Erk activation to support epidermal differentiation. J. Clin. Invest 2013; 123, 1556–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Getsios S, Simpson CL, Kojima SI, Harmon R, Sheu LJ, Dusek RL, et al. Desmoglein 1–dependent suppression of EGFR signaling promotes epidermal differentiation and morphogenesis. J Cell Bio. 2009; 185,1243–1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong MP, Cheang M, Yorida E, Coldman A, Gilks CB, Hunstman D, et al. Loss of desmoglein 1 expression associated with worse prognosis in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma patients. Pathology 2008; 40, 611–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tada H, Hatoko M, Tanaka A, Kuwahara M, and Muramatsu T. Expression of desmoglein I and plakoglobin in skin carcinomas. J Cutan Pathol 2000; 27, 24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nekrasova O, Harmon RM, Broussard JA, Koetsier JL, Godsel LM, Fitz GN, et al. Desmosomal cadherin association with Tctex-1 and cortactin-Arp2/3 drives perijunctional actin polymerization to promote basal cell delamination. Nature Communications 2018; 9:1053, 1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simpson CL, Kojima S, Cooper-Whitehair V, Getsios S, and Green KJ. Plakoglobin Rescues Adhesive Defects Induced by Ectodomain Truncation of the Desmosomal Cadherin Desmoglein 1 Implications for Exfoliative Toxin-Mediated Skin Blistering. Am. J. Pathol 2010; 177, 2921–2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharma VP, Eddy R, Entenberg D, Kai M, Gertler FB, and Condeelis J. Tks5 and SHIP2 regulate invadopodium maturation, but not initiation, in breast carcinoma cells. Curr. Biol 2013; 23, 2079–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vinci M, Box C, and Eccles SA. Three-Dimensional (3D) Tumor Spheroid Invasion Assay. J. Vis. Exp 2015; 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamaguchi H, Lorenz M, Kempiak S, Sarmiento C, Coniglio S, Symons M, et al. Molecular mechanisms of invadopodium formation: the role of the N-WASP-Arp2/3 complex pathway and cofilin. J. Cell Biol 2005; 168, 441–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tönisen F, Perrin L, Bayarmagnai B, van den Dries K, Cambi A, and Grigorijevic B. EP4 receptor promotes invadopodia and invasion in human breast cancer. Eur. J. Cell Biol 2017; 96, 218–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sodek KL, Brown TJ, and Ringuette MJ. Collagen I but not Matrigel matrices provide an MMP-dependent barrier to ovarian cancer cell penetration. BMC Cancer 2008; 8, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Getsios S, Huen AC, and Green KJ. Working out the strenght and flexibility of desmosomes. Nat. Rev 2004; 5, 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams KC, and Coppolino MG. SNARE-dependent interaction of Src, EGFR and b 1 integrin regulates invadopodia formation and tumor cell invasion. J. Cell Sci 2014; 127, 1712–1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grossman RL, Heath AP, Ferretti V, Varmus HE, Lowry DR, Kibbe WA, et al. Toward a share vision for cancer genomic data. New England Journal of Medicine 2016; 375:12, 1109–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brennan D, and Mahoney MG. Increased expression of Dsg2 in malignant skin carcinomas. Cell Adhesion and Migration 2009; 3, 148–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brennan D, Hu Y, Joubeh S, Choi YW, Whitaker-Menezes D, O’Brien T, et al. Suprabasal Dsg2 expression in transgenic mouse skin confers a hyperproliferative and apoptosis- resistant phenotype to keratinocytes. Journal of Cell Science 2007; 120, 758–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jögi A, Vaapil M, Johansson M, and Påhlman S. Cancer cell differentiation heterogeneity and aggressive behavior in solid tumors. Ups J Med Sci. 2012; 117, 217–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Todorović V, Desai BV, Schroeder Patterson MJ, Amargo EV, Dubash AD, Yin T, et al. Plakoglobin regulates cell motility through Rho- and fibronectin-dependent Src signaling. J. Cell Sci 2010; 123, 3576–3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yin T, Getsios S, Caldelari R, Kowalczyk AP, Muller EJ, Jones JCR, et al. Plakoglobin suppresses keratinocyte motility through both cell – cell adhesion-dependent and -independent mechanisms. PNAS 2005; 102, 5420–5425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu D, Shi M, Duan C, Chen H, Hu Y, Yang Z, et al. Downregulation of Erbin in Her2-overexpressing breast cancer cells promotes cell migration and induces trastuzumab resistance. Mol. Immunol 2013; 56, 104–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu Y, Chen H, Duan C, Liu D, Qian L, Yang Z, et al. Deficiency of Erbin induces resistance of cervical cancer cells to anoikis in a STAT3-dependent manner. Oncogenesis 2013; 2, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dai P, Xiong WC, and Mei L. Erbin Inhibits RAF Activation by Disrupting the Sur-8-Ras-Raf Complex *. J. Biol. Chem 2006; 281, 927–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dai F, Chang C, Lin X, Dai P, Mei L, Feng XH. Erbin Inhibits Transforming Growth Factor B Signaling through a Novel Smad-Interacting Domain. Mol. Cell. Biol 2007; 27, 6183–6194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang YZ, Zang M, Xiong WC, Luo Z, and Mei L. Erbin Suppresses the MAP Kinase Pathway *. The Journal of Biological Chemistry 2003; 278, 1108–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang H, Song Y, Wu Y, Guo N, Ma Y, Qian L. Erbin loss promotes cancer cell proliferation through feedback activation of Akt-Skp2-p27 signaling. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2015; 463, 370–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yao S, Zheng P, Wu H, Song LM, Ying XF, Xing C, et al. Erbin interacts with c-Cbl and promotes tumourigenesis and tumour growth in colorectal cancer by preventing c-Cbl-mediated ubiquitination and down-regulation of EGFR. J Path 2015; 236, 65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.