Atrial fibrillation (AF) is a common sequela of degenerative mitral regurgitation (DMR) and is frequently present in patients referred for surgery for DMR.(1) DMR may lead to the development of AF via left atrial (LA) volume and pressure overload, progressive atrial fibrosis, LA enlargement, and electroanatomic remodeling.(2–5) Progressive LA enlargement and remodeling – hallmarks of long-standing DMR – promote AF substrate by affecting cell coupling, altering conduction velocity, and promoting reentry.(6)

AF is associated with adverse cardiovascular events and decreased survival. The increased risk of stroke in patients with non-valvular AF is well established,(7) and long-term survival in AF patients is known to be reduced relative to the general population.(8) In patients undergoing various types of cardiac surgery, pre-existing AF is associated with reduced postoperative survival.(9,10) It is currently unknown, however, if earlier surgical intervention prior to or shortly after the development of AF leads to improved outcomes. This is an important distinction, since a curative surgical therapy – namely mitral valve (MV) repair surgery – exists for patients with DMR.

MV repair for DMR results in excellent long-term survival – similar to that observed in the general population – particularly if performed earlier in the disease process.(11,12) If AF is convincingly demonstrated to be associated with worse postoperative long-term outcomes and if surgical intervention mitigates that risk, then guideline recommendations for MV repair surgery may need to be altered.

Small, single-center studies have suggested that AF negatively affects early- and long-term prognosis post-MV repair surgery.(13,14) In this issue of the Journal, Grigioni and colleagues further analyzed this issue in 2,425 DMR patients with very long-term follow up.(15) These investigators used their previously described multicenter international database,(16) the largest consecutive collection of patients diagnosed with DMR (specifically flail mitral leaflet) by echocardiography between 1980 and 2005. DMR patients were followed for occurrence of cardiovascular complications, MV surgery or both over a period of 9.1 ± 5.4 years. Paroxysmal or persistent AF was present in 32% of patients at baseline and sinus rhythm in 68%, and MV surgery was eventually performed in 78% of all patients. The progressive nature of AF in DMR patients was confirmed by the 24% and was 36% incidence of new AF during 10-year follow-up in patients initially in sinus rhythm and paroxysmal AF.

AF was a strong predictor of death during follow-up in this series, even after adjusting for other known risk factors and for class I recommendations for MV surgery.(17,18) The hazard ratio for death was higher in patients with persistent AF (1.94, 95% CI 1.66 – 2.24) than paroxysmal AF (1.46, 95% CI 1.20 – 1–76), with a more pronounced negative prognostic effect in patients without class I triggers for surgery. Surgery was highly protective against death (HR 0.26, CI 0.22 – 0.30), with no significant interactive effect between surgery and heart rhythm. The likelihood of MV repair (as opposed to replacement) was lower in patients with persistent AF than other patients (82% vs 90%, p < 0.001), and perioperative mortality rate was higher in patients with preoperative AF or class I indicators for surgery (2.7%) than in patients without those factors (0.7%, p = 0.002). Landmark analysis revealed a beneficial effect of surgery when performed within 6 months of diagnosis, regardless of rhythm status. Most importantly, the presence of AF was a strong independent predictor of long-term death and cardiovascular death post-MV surgery, with an incremental increase in risk for patients with more AF burden (persistent versus paroxysmal AF).

The above data make a strong argument supporting MV repair surgery in patients with DMR, particularly once AF is observed. It is important to note, however, that only 5.2% of AF patients underwent concomitant atrial ablation at the time of surgery in this study. The beneficial effect of MV surgery may have therefore been underestimated, since AF ablation has been demonstrated to be associated with reduced postoperative mortality and stroke rates following MV surgery.(19,20)

The mechanisms by which AF can lead to worse outcomes in DMR despite MV surgery are manifold, including stroke and tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy. Atrial remodeling and fibrosis resulting from DMR are unlikely to be reversed by valve surgery.

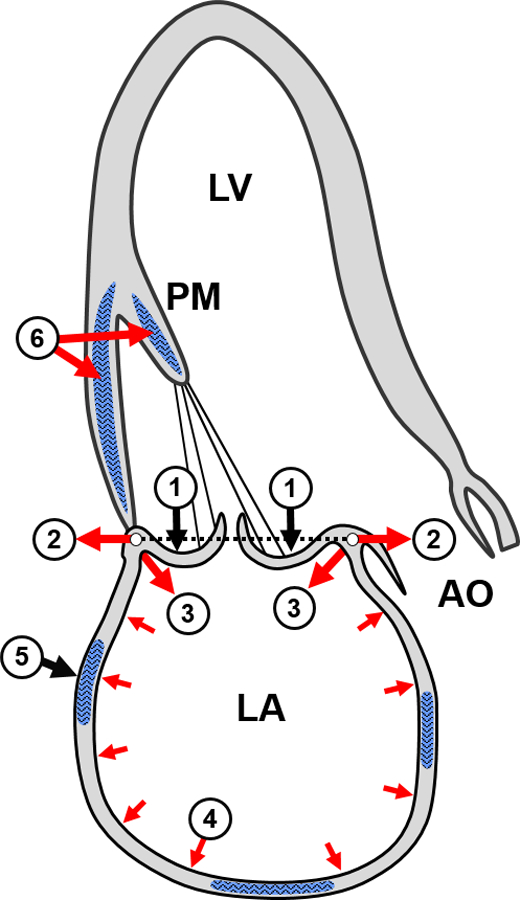

Atrial dilation and stretch promote AF induction and sustainability,(21) and both MR and rapid atrial pacing promote interstitial fibrosis and inflammation in the dilating LA with heterogeneous conduction slowing that facilitates AF.(22–24) Basal myocardial left ventricular fibrosis is also common in patients with DMR.(25) We can postulate that atrial fibrosis reflects abnormal wall stresses from the prolapsing leaflets, expanding annulus and dilated atrium (Figure1, 2–4)(26–28) and impinging MR jets, possibly augmented by abnormal interstitial mechanosensing due to DMR-causing mutations.(29)

Figure 1.

Potential fibrotic stimuli in MV prolapse (①) include augmented systolic annular expansion, (②), basal LA wall tension (③), and left atrial (LA) stretch (④), inducing LA fibrosis (⑤) in parallel with basal LV fibrosis from basal LV tension and papillary muscle (PM) traction (⑥). (Mark Handschumacher)

Surgery may prevent the progression of scar formation in the atrium but is not expected to eliminate fibrosis generated by DMR-induced pressure and volume overload. In fact, once AF develops, it probably leads to an increasing degree of fibrosis - AF begets AF- which in turn results in increased substrate for AF.(30) This vicious cycle is likely to lead to continued worsening of the AF burden despite valve surgery and to reduce survival compared with patients free of AF, as described above.

Future directions include MRI comparison of atrial fibrosis in patients with DMR with and without AF, and testing the potential for early intervention to reduce progression from paroxysmal to persistent AF. Novel therapeutic agents may reduce fibrosis through modifying growth factor and fibronectin stimuli.(31,32)

The presence of AF in patients with DMR is currently rated as a class IIa recommendation for MV surgery in the both American and European guidelines on valvular heart disease.(17,18) A class I recommendation can be applied when there is strong supportive evidence that a treatment option is beneficial, even if obtained from a non-randomized study (i.e., class I, level B). Given the strength of the above evidence from Grigioni and colleagues, it may be time to re-evaluate the guidelines regarding the presence of AF in DMR patients. Since MV repair surgery has been demonstrated to be a very safe and effective option for DMR,(1,11,12,16,33) it seems reasonable to recommend this therapy in patients with new onset AF, even in the absence of other surgical indications. In addition to the timing of surgery, this evidence also suggests that surgical ablation for AF should also be considered concomitantly with valve surgery in patients with AF and DMR. The optimal time to intervene in patients with DMR may therefore be earlier than we thought.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants R01HL128099 and HL141917 and by the Ellison Foundation, Boston, MA (R.A.L.).

Footnotes

Dr. Borger discloses speaker’s honoraria and/or consulting (all<$10000 per year) for Edwards, Lifesciences, Medtronic, Abbott (St. Jude Medical), and CryoLife. Dr. Mansour discloses industry relationshipts related to the field of AF ablation and stroke prevention: Consultant: Biosense Webster, Abbott, Medtronic, Boston Scientific; Research grants: Biosense Webster, Abbott, Boston Scientific, Pfizer, Bohreinger Ingelheim; Equity: EPD Solutions. Dr. Levine has no financial relations to disclose.

References

- 1.Seeburger J, Borger MA, Doll N et al. Comparison of outcomes of minimally invasive mitral valve surgery for posterior, anterior and bileaflet prolapse. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;36:532–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allessie M, Ausma J, Schotten U. Electrical, contractile and structural remodeling during atrial fibrillation. Cardiovascular research 2002;54:230–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JG, Newton-Cheh C, Almgren P et al. Assessment of conventional cardiovascular risk factors and multiple biomarkers for the prediction of incident heart failure and atrial fibrillation. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2010;56:1712–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morillo CA, Klein GJ, Jones DL, Guiraudon CM. Chronic rapid atrial pacing. Structural, functional, and electrophysiological characteristics of a new model of sustained atrial fibrillation. Circulation 1995;91:1588–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wijffels MC, Kirchhof CJ, Dorland R, Allessie MA. Atrial fibrillation begets atrial fibrillation. A study in awake chronically instrumented goats. Circulation 1995;92:1954–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kottkamp H. Human atrial fibrillation substrate: towards a specific fibrotic atrial cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2731–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation 1991;22:983–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnabel RB, Yin X, Gona P et al. 50 year trends in atrial fibrillation prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and mortality in the Framingham Heart Study: a cohort study. Lancet 2015;386:154–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saxena A, Virk SA, Bowman S, Chan L, Jeremy R, Bannon PG. Preoperative atrial fibrillation portends poor outcomes after coronary bypass graft surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;155:1524–1533 e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalavrouziotis D, Buth KJ, Vyas T, Ali IS. Preoperative atrial fibrillation decreases event-free survival following cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2009;36:293–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.David TE, Armstrong S, Sun Z, Daniel L. Late results of mitral valve repair for mitral regurgitation due to degenerative disease. Annals of Thoracic Surgery 1993;56:7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Badhwar V, Peterson ED, Jacobs JP et al. Longitudinal outcome of isolated mitral repair in older patients: results from 14,604 procedures performed from 1991 to 2007. Ann Thorac Surg 2012;94:1870–7; discussion 1877–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varghese R, Itagaki S, Anyanwu AC, Milla F, Adams DH. Predicting early left ventricular dysfunction after mitral valve reconstruction: the effect of atrial fibrillation and pulmonary hypertension. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:422–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coutinho GF, Garcia AL, Correia PM, Branco C, Antunes MJ. Negative impact of atrial fibrillation and pulmonary hypertension after mitral valve surgery in asymptomatic patients with severe mitral regurgitation: a 20-year follow-up. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2015;48:548–55; discussion 555–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grigioni F, Benfari G, Vanoverschelde JL, et al. Very long-term prognostic and therapeutic implications of atrial fibrillation complicating degenerative mitral regurgitation. Results from a large multicenter international registry. JACC 2018; In press

- 16.Suri RM, Vanoverschelde JL, Grigioni F et al. Association between early surgical intervention vs watchful waiting and outcomes for mitral regurgitation due to flail mitral valve leaflets. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2013;310:609–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO et al. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2017;70:252–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ et al. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2739–2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badhwar V, Rankin JS, Ad N et al. Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation in the United States: Trends and Propensity Matched Outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg 2017;104:493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ad N, Holmes SD, Massimiano PS, Rongione AJ, Fornaresio LM. Long-term outcome following concomitant mitral valve surgery and Cox maze procedure for atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2018;155:983–994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zou R, Kneller J, Leon LJ, Nattel S. Substrate size as a determinant of fibrillatory activity maintenance in a mathematical model of canine atrium. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology 2005;289:H1002–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun Q, Tang M, Pu J, Zhang S. Pulmonary venous structural remodeling in a canine model of chronic atrial dilation due to mitral regurgitation. The Canadian journal of cardiology 2008;24:305–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verheule S, Wilson E, Everett Tt, Shanbhag S, Golden C, Olgin J. Alterations in atrial electrophysiology and tissue structure in a canine model of chronic atrial dilatation due to mitral regurgitation. Circulation 2003;107:2615–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li D, Fareh S, Leung TK, Nattel S. Promotion of atrial fibrillation by heart failure in dogs: atrial remodeling of a different sort. Circulation 1999;100:87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitkungvan D, Nabi F, Kim RJ et al. Myocardial Fibrosis in Patients With Primary Mitral Regurgitation With and Without Prolapse. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2018;72:823–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi A, Fukuda S, Mahara K et al. Left Atrial Remodeling in Segmental vs. Global Mitral Valve Prolapse- Three-Dimensional Echocardiography. Circ J 2016;80:2533–2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clavel MA, Mantovani F, Malouf J et al. Dynamic phenotypes of degenerative myxomatous mitral valve disease: quantitative 3-dimensional echocardiographic study. Circulation Cardiovascular imaging 2015;8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Fukuda S, Song JK, Mahara K et al. Basal Left Ventricular Dilatation and Reduced Contraction in Patients With Mitral Valve Prolapse Can Be Secondary to Annular Dilatation: Preoperative and Postoperative Speckle-Tracking Echocardiographic Study on Left Ventricle and Mitral Valve Annulus Interaction. Circulation Cardiovascular imaging 2016;9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levine RA, Jerosch-Herold M, Hajjar RJ. Mitral Valve Prolapse: A Disease of Valve and Ventricle. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2018;72:835–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allessie MA. Atrial electrophysiologic remodeling: another vicious circle? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1998;9:1378–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeong D, Lee MA, Li Y et al. Matricellular Protein CCN5 Reverses Established Cardiac Fibrosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2016;67:1556–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Travers JG, Kamal FA, Valiente-Alandi I et al. Pharmacological and Activated Fibroblast Targeting of Gbetagamma-GRK2 After Myocardial Ischemia Attenuates Heart Failure Progression. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2017;70:958–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castillo JG, Anyanwu AC, Fuster V, Adams DH. A near 100% repair rate for mitral valve prolapse is achievable in a reference center: implications for future guidelines. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:308–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]