Abstract

Background:

Reliable and valid tools to screen for malnutrition in the intensive care unit (ICU) remain elusive. The Sarcopenia Index (SI) [(serum creatinine/serum cystatin C)*100], could be an inexpensive, objective tool to predict malnutrition. We evaluated the SI as a screening tool for malnutrition in the ICU and compared it to the modified-NUTRIC score.

Materials and Methods:

This was a historical cohort study of ICU patients with stable kidney function admitted to Mayo Clinic ICUs between 2008–2015. Malnutrition was defined by the Subjective Global Assessment. Diagnostic performance was evaluated with the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) and multivariable logistic regression.

Results:

Of the 398 included patients, 181 (45%) had malnutrition, with 34 (9%) scored as severely malnourished. The SI was significantly lower in malnourished patients than in well-nourished patients (64±27 vs. 72±25; P = 0.002), and reductions in SI corresponded to increased malnutrition severity (P =0.001). As a screening tool, the SI was an indicator of malnutrition risk (AUC 0.61) and performed slightly better than the more complex modified-NUTRIC score (AUC = 0.57). SI cut-offs of 101 and 43 had >90% sensitivity and >90% specificity, respectively, for the prediction of malnutrition. Patients with a low SI (≤ 43) had a significantly higher risk of mortality (HR=2.61, 95% CI 1.06–6.48, P = 0.038).

Conclusion:

The frequency of malnutrition was high in this critically ill population, and it was associated with a poor prognosis. The SI could be used to assess nutritional risk in ICU patients.

Keywords: Cystatin C, creatinine, intensive care unit, sarcopenia, nutrition, frailty

Introduction

Malnutrition affects approximately 50% of critically ill patients and independently predicts poor clinical outcomes1. Hospitalized patients with malnutrition experience a 4-fold higher risk of mortality than well-nourished patients2. The cost of care is higher in malnourished patients, and those who survive critical illness experience longer lengths of stay, greater incidences of infections, impaired wound healing and are more often discharged to care facilities1.

Given the significant impact of malnutrition on the health and outcomes of hospitalized patients, the Joint Commission mandates nutrition and functional screening within 24-hours of inpatient admission as appropriate for the patients’ needs and condition3. Early efforts to identify malnutrition involved the use of weight or body mass index (BMI) thresholds; however, these poorly reflect nutritional status or muscle mass4. Overweight or obese patients may have a low muscle mass, referred to as sarcopenic obesity, which is associated with a 2- to 5-fold higher risk of death5,6. More than 30 clinical and laboratory tools have been tested to screen hospitalized patients for risk or presence of malnutrition7. These tools are most often performed by nurses upon admission based on subjectively reported dietary or weight changes, gastrointestinal symptoms and serum biomarkers such as albumin, pre-albumin, or C-reactive protein8. Such a detailed subjective history is often unavailable or inaccurate in critically ill patients, weight changes may reflect edema, and the serum biomarkers are often nonspecific for malnutrition as they are acute phase proteins influenced by inflammation9.

Recently, the sarcopenia index (SI), defined as the [(serum creatinine/serum cystatin C)*100], was found to be an inexpensive, accessible, objective tool to predict skeletal muscle mass in intensive care unit patients10,11. This ratio capitalizes on the unique cellular origins of kidney biomarkers, creatinine from skeletal muscle and cystatin C from nucleated cells. Among patients with stable kidney function, a low index (relatively low serum creatinine compared to cystatin C) would indicate that the patient has less skeletal muscle available for creatinine production, a screening tool for reduced muscle mass. We hypothesized the SI would be a superior screening tool for malnutrition in intensive care unit (ICU) patients than existing metrics.

Materials and Methods

Setting and participants

In this historical cohort study, we evaluated the SI as a predictor of malnutrition and outcomes in critically ill adults (≥ 18 years of age) hospitalized in a Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN medical or surgical ICU between 2008 and 2015. Eligible individuals were obtained from two previously collected cohorts of patients with both serum creatinine and serum cystatin C drawn during their intensive care unit (ICU) admission12–14. Briefly, included patients were those with sepsis, shock or major trauma hospitalized in the ICU. Individuals with unstable renal function [e.g., evolving or recovering acute kidney injury (AKI), need for renal replacement therapy] or who did not authorize their medical record for review in the state of MN were excluded from the study. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved the protocol and the requirement for informed consent was waived due to the minimal risk nature of the study. This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

During the study timeframe, no specific cystatin C protocol was used and the evaluation was at the discretion of the inter-professional care team. At the study center during this interval a multilayered approach to nutrition screening was part of routine care. Within 24-hours of all admissions, bedside nurses asked a series of screening questions regarding weight loss, poor intake, dysphagia and pregnancy. If the patient or family responded positively to any of these questions, a formal consult was ordered for a comprehensive Registered Dietitian/Nutritionist (RDN) assessment within 48 hours. The RDN then used standard nutrition assessment techniques to determine presence and degree of nutritional compromise. While it was standard practice to conduct these nutrition assessments at the study center during this period, the designation of malnutrition and severity staging for this study was assessed independently and in duplicate on all patients with these kidney biomarkers using the procedures outlined below.

Measures

Data extracted from the electronic health record for this study included age, sex, race, height, weight, body surface area (BSA), BMI, and severity of illness scores [acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE III) and sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) scores within 24-hours of ICU admission]. Ideal body weight (kg) was calculated as = 45.5 + 2.3*(height in inches – 60) for women and 50 + 2.3*(height in inches – 60) for men. These data were used to calculate the patient’s modified-NUTRIC score. The NUTRIC score (maximum score 10) is a validated tool to identify ICU patients most likely to benefit from nutrition optimization to decrease 28-day and 6-month mortality (higher score indicates greater risk for severe malnutrition)15,16. The modified NUTRIC score (maximum score 9) retains the components age, APACHE II score, SOFA score, number of co-morbidities, and days from hospital to ICU admit, but excludes the interleukin-6 concentration used in the original tool as this is not routinely assessed. Among patients with a high modified-NUTRIC score, increased caloric intake was associated with a reduced risk of death16.

Serum creatinine (mg/dL) measurement was assayed using the standardized (isotope dilution mass spectrometry traceable) enzymatic creatinine assay (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Serum cystatin C (mg/L) was measured with a particle-enhanced turbidimetric assay (Gentian AS, Moss, Norway). This assay is traceable to the same international certified cystatin C reference material (ERM-DA471/IFCC) used to develop the cystatin C-based CKD-EPI equations. The SI was calculated as [(serum creatinine/serum cystatin C)x100]. In patients with stable kidney function, the glomerular filtration rate aspect of the serum creatinine and cystatin C effectively cancels out. Thus the non-renal determinants of these two serum markers determine the ratio. Previous studies identified high sensitivity and high specificity cut-offs (>90%) for SI of 98 and 53, respectively for prediction of a low skeletal muscle index on abdominal CT11.

The primary endpoint of malnutrition was defined by the Subjective Global Assessment (SGA)17, a recommended tool for malnutrition staging by clinical guidelines18–20. The SGA includes six domains: weight change, dietary intake, gastrointestinal symptoms, functional capacity, disease and its relation to nutritional requirements, and physical exam findings of loss of subcutaneous fat, muscle wasting, edema, and ascites. These domains are consistent with those noted in the recent Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition Consensus Criteria21 and have been operationalized in the SGA using a standardized instrument. Based on the results of each of these domains, a reviewer assigns an overall SGA rating of well-nourished, mild-moderate malnutrition, or severe malnutrition. This overall SGA assignment reflects the reviewer’s impression about the patient’s nutritional status based on the findings in each of the six domains, but it is not a direct quantitative summation of their results17. Two study investigators, one physician (TK) and one dietitian (SD), independently reviewed the electronic health records for all patients up to 7-days before and after the kidney biomarker levels to assign the SGA rating (Κ = 0.69). Reviewers were instructed to avoid the laboratory data section of the medical record to preserve blinding, which would not be expected to adversely affect the SGA assessment as no laboratory data is included in the questionnaire and the SI is not automatically calculated in our electronic health record. In cases of discrepancy, a third reviewer (JH, a dietitian) was engaged, reviewed the record in detail and cases were adjudicated by consensus among the three reviewers.

Data analysis

Continuous data were summarized with the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile range (IQR), depending on distribution. Student’s t-test and the chi-square test were used to compare baseline characteristics between those with and without malnutrition. The SI was compared between patients with and without malnutrition using the t-test (any malnutrition where mild-to-moderate and severe categories were combined) and the Kruskal Wallis Test (well nourished, mild-to-moderate malnutrition, and severe malnutrition). A logistic regression model was fit to determine the independent association between the SI and malnutrition after adjustment for confounders. Results were reported as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Secondarily we compared the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) between the SI and the modified-NUTRIC score for prediction of malnutrition. We also explored the relationship between malnutrition and ICU and hospital length of stay, and 28- and 90-day mortality with Cox-proportional hazards models. Results were reported as hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). ICU and hospital length of stay summaries were computed using Kaplan-Meier estimation accounting for the competing risk of death during the stay. A two-sided alpha of 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and all analyses were performed with SAS 9.4 and JMP 13.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

398 patients had both serum creatinine and cystatin C concentrations measured during the study timeframe. The median (IQR) time from ICU admission to SI was 1.3 (0.3, 2.3) days. The sample included 229 (58%) males, 267 (67%) patients with sepsis, and the mean ± SD weight and BMI were 82±25 kg and 28±8 kg/m2, respectively (Table 1). In this sample of patients, actual body weight was a median of 22% greater than ideal body weight (IQR +6%, +43%; range: −39% to +238%).

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics and demographic data

| Characteristic | All Patients (N=398)a | Malnutritiona (N=181) | No Malnutritiona (N=217) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65 ± 15 | 66 ± 15 | 64 ± 16 | 0.1 |

| Age ≥ 65 years (N; %) | 233 (59) | 111 (61) | 122 (56) | 0.3 |

| Male (N; %) | 229 (58) | 99 (55) | 130 (60) | 0.3 |

| Caucasian (N; %)2 | 371 (97) | 170 (97) | 201 (97) | 0.9 |

| Weight (kg) | 82 ± 25 | 74 ± 20 | 88 ± 27 | <0.001 |

| Ideal body weight (kg) | 66 ± 12 | 62 ± 12 | 65 ± 11 | 0.05 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28 ± 8 | 26 ± 6 | 30 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| < 18.5 kg/m2 | 19 (5) | 16 (9) | 3 (1) | <0.001 |

| Body surface area (m2) | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | <0.001 |

| APACHE III score | 68 ± 21 | 71 ± 22 | 65 ± 20 | 0.003 |

| SOFA score | 5.2 ± 3.3 | 5.6 ± 3.5 | 4.9 ± 3.1 | 0.04 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 5.6 ± 3.7 | 6.1 ± 3.5 | 5.3 ± 3.8 | 0.02 |

| Sepsis (N; %) | 267 (67) | 142 (79) | 125 (58) | <.001 |

| Septic shock (N; %) | 71 (18) | 42 (23) | 29 (13) | 0.01 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation (N; %) | 217 (55) | 100 (57) | 117 (54) | 0.6 |

| Renal parameters | ||||

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 0.2 |

| Cystatin C (mg/L) | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 0.02 |

| Cockcroft-Gault (mL/min) | 101 ± 52 | 95 ± 52 | 106 ± 51 | 0.03 |

| CKD EPIcr-cysC eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 75 ± 30 | 70 ± 28 | 80 ± 30 | <0.001 |

| Sarcopenia Index | 68.5 ± 26.2 | 63.9 ± 27.2 | 72.3 ± 24.8 | 0.002 |

| Modified-NUTRIC Score | 4.2 ± 1.9 | 4.5 ± 1.9 | 3.9 ± 1.9 | 0.004 |

| ≥ 6 | 96 (24) | 53 (29) | 43 (20) | 0.03 |

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation score; CKD-EPI eGFR, Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaborative estimated glomerular filtration rate; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score

Values expressed as mean ± SD unless noted

The modified NUTRIC score (higher score indicates greater severity of illness) is comprised of age, APACHE II, SOFA, number of co-morbidities, and days from hospital to ICU admit

Prediction of malnutrition

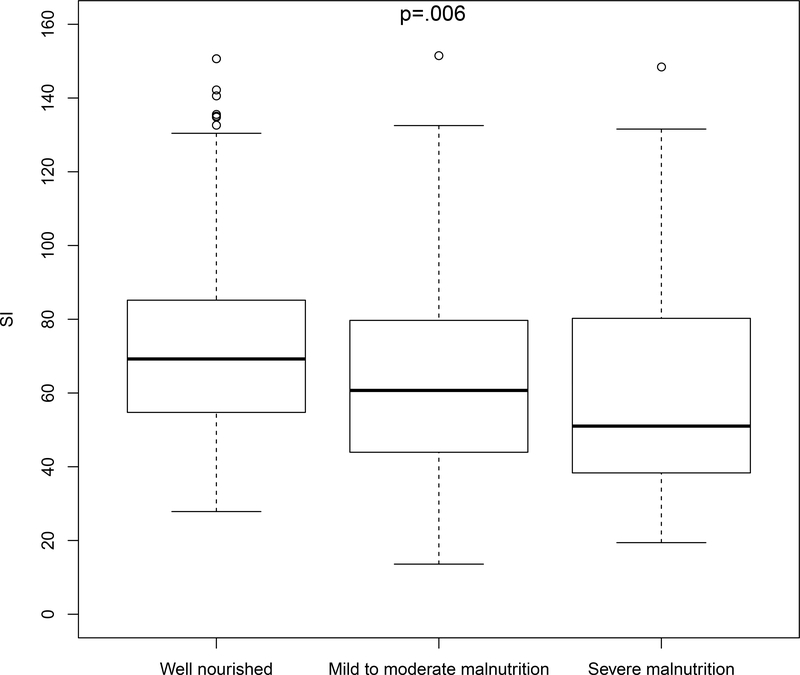

Malnutrition was present in 181 (45%) patients based on the SGA; of those, 147 (81%) cases were judged to be mild to moderate malnutrition, and 34 (19%) cases were considered severe malnutrition. In the 20 patients where the SI was calculated from biomarkers more than 7-days into the hospital admission, malnutrition was present in 15 (75%) cases, 6 of which were severe (30%). The SI was significantly lower (indicative of lower muscle mass) in patients with malnutrition compared to well-nourished patients (64±27 vs. 72±25, respectively; P = 0.002). SI was inversely associated with increasing malnutrition severity [median (IQR): Well-nourished 69 (55, 85); mild to moderate malnutrition: 60 (44, 80), severe malnutrition: 51 (37, 81); P = 0.006] (Figure 1). In the 28 (7%) patients with an actual weight less than 90% of their ideal body weight, the SI was 54 (44, 87). Among the 19 (5%) patients with a BMI < 18.5 kg/m2, the median SI was 50 (41, 81).

Figure 1.

Boxplot of median SI according to nutritional status (well-nourished N = 217; mild-to-moderate malnutrition N = 147; severe malnutrition N = 34). The SI was significantly associated with malnutrition severity (P = 0.006), with a lower median SI (indicative of reduced muscle mass) in patients with higher severity of malnutrition. Abbreviation: SI, Sarcopenia Index

On its own, the SI was a fair predictor of malnutrition (AUC = 0.61) and with > 90% sensitivity and > 90% specificity cut-offs of 101 and 43. As a comparison, the AUC for prediction of malnutrition with the modified-NUTRIC score was 0.57. After adjustment for age, sex, APACHE III score, SOFA score, and BMI, the SI remained independently predictive of malnutrition [OR per 10-unit decrease in SI 1.15 (1.05, 1.26); P = 0.002]. (Table 2). When stratified into 3 groups based on these cut offs (< 43, 43 to <101, and ≥ 101), the overall agreement for well-nourished, mild to moderate malnutrition, and severe malnutrition was 34%; for the modified-NUTRIC score (0–3, 4–6, 7–9) it was 46% (Table 3).

Table 2.

Multivariable logistic regression models for predictors of malnutrition

| SI | Modified NUTRICa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-Value |

| Age (per decade) | 1.02 (0.87, 1.18) | 0.9 | - | - |

| Male sex | 1.05 (0.66, 1.64) | 0.9 | 1.11 (0.73, 1.69) | 0.6 |

| APACHE III (per 5-units) | 1.06 (0.98, 1.14) | 0.2 | - | - |

| SOFA | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) | 0.8 | - | - |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2) | 0.91 (0.88, 0.95) | <0.001 | 0.92 (0.88, 0.95) | <0.001 |

| SI (per 10-units) | 0.87 (0.79, 0.95) | 0.002 | - | - |

| Modified NUTRIC (per 1-unit) | - | - | 1.20 (1.07, 1.34) | 0.002 |

| AUC ROC | 0.689 | 0.675 | ||

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation score; AUC ROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; BMI, body mass index; OR (95% CI), Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval; SI, Sarcopenia index; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score

The modified NUTRIC score (higher score indicates greater severity of illness) is comprised of age, APACHE II, SOFA, number of co-morbidities, and days from hospital to ICU admit.

Therefore a reduced multivariable model with sex, BMI, and the score was fit to avoid duplication of covariates

Table 3.

| SI | SGA Well Nourished | SGA Mild/Moderate Malnutrition | SGA Severe Malnutrition | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥ 101 | 27 (7) | 13 (3) | 5 (1) | 45 (11) |

| >43 – <101 | 170 (43) | 100 (25) | 19 (5) | 289 (73) |

| ≤43 | 20 (5) | 34 (9) | 10 (25) | 64 (16) |

| Totals | 217 (55) | 147 (37) | 34 (9) | 398 (100) |

SGA, Subjective global assessment; SI, Sarcopenia Index

Values in the table represent N (%) in that cell

Percent agreement for the SI and SGA severity classification was 34.4%

Clinical outcomes

Secondary analyses were conducted to explore the relationship between malnutrition and clinical outcomes. Median (IQR) ICU and hospital lengths of stay were 4 (2, 9) days and 13 (8, 24) days, respectively. ICU and hospital length of stay was significantly longer in malnourished patients (P < 0.001 for both analyses). All-cause mortality at 28- and 90-days was 13% and 23%, respectively, and malnourished patients had a 4-fold higher risk of death than patients who were well nourished [HR 3.99 (95% CI 2.48, 6.40) (P < 0.001)] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve for 90-day outcomes according to nutritional status. Greater degrees of malnutrition were associated with a greater risk of death [mild-moderate malnutrition: HR 3.63 (95% 2.21, 5.95) (P < 0.001); severe malnutrition HR 5.62 (95% CI 3.0, 10.53) (P < 0.001)]. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio

When stratified based on the high-sensitivity and high-specificity cut-offs, patients with an SI ≤ 43 experienced a 2.6-fold higher risk of death by 90-days than patients with an SI ≥ 101 [HR 2.61 (95% CI 1.06, 6.48); P = 0.038] (Figure 3). SI no longer independently predicted mortality when age or malnutrition were included in the model (P = 0.17 and P = 0.21, respectively). No significant collinearity or interactions were observed between SI and these variables in the mortality model.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curve for 90-day outcomes grouped based on SI ≤ 43 (high specificity cut-off), SI between 43 and 101 (high-sensitivity cut-off), and SI ≥ 101 (reference). The risk of death in patients with an SI ≤ 43 was significantly greater [HR 2.61 (95% CI 1.06, 6.48), P = 0.038]. For patients with an SI between 43 and 101, the HR for death was 1.71 (95% CI 0.74–3.94) (P = 0.21). Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; SI, Sarcopenia Index

Discussion

In this retrospective study of 398 critically ill patients, we demonstrated that the SI is a fair screening tool for malnutrition in critically ill patients and performs at least as well as the modified-NUTRIC score even after adjustment for relevant covariates. Further, the SI significantly predicted the severity of malnutrition and a low SI was associated with increased ICU and hospital length of stay as well as mortality. These data suggest that SI cut-offs of 101 and 43, identify risk for malnutrition in patients with >90% sensitivity (for screening purposes) and >90% specificity (in order to rule in patients for interventions targeted at nutrition optimization), respectively.

Critically ill patients requiring organ support commonly experience anorexia and an inability to feed volitionally by mouth for extended periods. Without nutrition therapy, in the form of enteral or parenteral nutrition, the resultant energy deficit can contribute to lean-tissue wasting and adverse outcomes4,22. The catabolic response to critical illness is much more pronounced than that evoked by fasting in healthy individuals since the energy deficit in acutely ill patients is superimposed on immobilization, extracorporeal organ support, inflammation and upregulation of catabolic hormones. Coupled with pre-existing chronic comorbidities, sarcopenia, frailty or malnutrition, this multitude of factors explains why the prevalence of malnutrition in the ICU reaches 38–78%1,23.

A timely risk stratification for malnutrition is important to institute preventative and therapeutic strategies that limit malnutrition complications in the critically ill. Current guidelines recommend that ICU patients undergo an initial nutrition risk screening within 24–48 hours of admission3,23. Many screening and assessment tools have been trialed to assess nutritional status7. Anthropometric parameters including weight and BMI are unreliable in the assessment of nutrition status or for monitoring adequacy of nutrition therapy in the ICU4. The use of the traditional serum protein markers (albumin, prealbumin, transferrin, retinol binding protein) in critically ill patients may reflect an acute-phase response to critical illness (increases in vascular permeability and reprioritization of hepatic protein synthesis) rather than nutritional status9,24. Only the nutritional risk screening (NRS) 2002 and the NUTRIC score determine both nutrition status and disease severity and are two tools recommended by consensus guidelines for nutrition screening. In clinical trials, when high-risk patients are identified with these tools and provided targeted early nutrition therapy, studies noted reductions in nosocomial infections, complications, and improved survival15,25. Yet these tools are complex and difficult to apply by the bedside clinician. The NRS 2002 relies on subjective data about dietary intake that might be unavailable in critically ill patients. The NUTRIC score includes complex calculations as with the APACHE II or SOFA scores. Our study is the first to demonstrate that the simple, reproducible SI is a good predictor of nutrition risk and performed similarly to these existing tools. In fact, after adjustment for age, sex, APACHE III score, SOFA score and BMI, the SI remained an independent predictor of malnutrition in critically ill patients. In contrast to previous more complex tools, the SI is independent of subjectively provided information, weight data, and complex calculations, making it a favorable alternative for clinical decision support and busy bedside clinicians.

Our findings are consistent with previous work on the SI. We recently demonstrated in ICU patients and lung transplant recipients, that the SI exhibited good prediction of skeletal muscle mass quantified at the L3 – L4 level on abdominal CT scan10,26. Early evidence suggested that patients with a higher SI (indicative of greater muscle mass) experienced earlier ventilator liberation, more rapid discharge from the ICU and hospital, and a lower 90-day mortality10. We validated our findings in an independent cohort and confirmed that a reduced SI (indicative of lower muscle mass) was associated with poorer outcomes including frailty11. These findings differ somewhat from a recently published study in 371 community-dwelling adults ≥ 60 years with normal kidney function27. These authors found that SI exhibited only modest accuracy for prediction of muscle mass or sarcopenia depending on the definition utilized. We hypothesize that their lower incidence of reduced muscle mass (19–57% vs. 70%), decreased overall prevalence of sarcopenia (11–25%), and differences in the study populations (community vs. ICU) and definitions utilized could explain these disparate findings. Further study is needed to explore SI performance in patients with a high pre-test probability of sarcopenia.

Interestingly, there is a similarity between the non-renal determinants of these biomarkers and the factors that influence skeletal muscle catabolism. Creatinine is affected not only by muscle mass, but can be influenced by dietary intake and large volume resuscitation. Cystatin C concentrations may be affected by thyroid function, inflammation, hypercatabolic states, and corticosteroid use28. In critically ill patients without AKI, it has been shown that over of 1 week mean creatinine concentrations downtrend by 10–25%, whereas cystatin C concentrations stay stable or uptrend slightly29,30. It is somewhat unlikely that these patterns exclusively reflect changes to underlying kidney function. Rather they are more likely indicative of reduced creatinine production from deconditioning or increased cystatin C concentrations from inflammation. In the SI, a 20% decrease in serum creatinine from 1.0 to 0.8 mg/dL and a stable cystatin C would yield a decrease in the SI by 14 points. Thus, in patients with stable kidney function, the SI could be sufficiently dynamic to monitor a patient’s clinical course and response to interventions.

Our study has certain limitations. Despite the significant effort that has been invested in defining malnutrition, still no consistent criterion standard exists. In the present study investigators retrospectively applied the SGA17 to assign nutritional status. The assessment was limited by available information in the electronic health record and may have been affected by incomplete documentation and missing data. To improve the rigor of the nutrition assessment, trained study team members with expertise in the field, masked to the SI, independently and in duplicate reviewed all records. In cases of discrepancy, a third investigator (dietitian) reviewed the record in detail and cases were adjudicated by consensus. Another limitation is that the timing and ordering of kidney biomarkers were not standardized and could have introduced bias. We found that 95% of individuals were evaluated within 7-days of hospital admission. Finally, uptake of SI as a malnutrition screening tool is fundamentally affected by availability of the cystatin C test. Use of cystatin C test in acute care is increasing, but it is not yet widespread. A recent survey indicated that 19% of providers in critical care or nephrology use cystatin C to inform their practice31. The test can be performed on existing laboratory test platforms and is relatively inexpensive at approximately $4 per test for the reagent32. Despite these limitations, the methodologic strengths of our study include the size of our cohort and rigor with which the endpoint was adjudicated.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the SI is a simple calculation from kidney function markers that can be used to identify critically ill patients with different degrees of malnutrition risk and predict poor ICU and hospital outcomes. Future studies should be conducted to prospectively validate the SI and explore clinical applications for nutrition therapy.

Table 4.

Degree of agreement between the Modified-NUTRIC score strata and nutritional status according to SGA classificationa,b,c

| Modified NUTRIC | SGA Well Nourished | SGA Mild/Moderate Malnutrition | SGA Severe Malnutrition | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–3 | 88 (22) | 46 (12) | 8 (2) | 142 (36) |

| 4–6 | 113 (28) | 87 (22) | 17 (4) | 217 (55) |

| 7–9 | 16 (4) | 14 (4) | 9 (2) | 39 (10) |

| Totals | 217 (55) | 147 (37) | 34 (9) | 398 (100) |

SGA, Subjective global assessment

Values in the table represent N (%) in that cell

The modified NUTRIC score (higher score indicates greater severity of illness) is comprised of age, APACHE II, SOFA, number of co-morbidities, and days from hospital to ICU admit.

Percent agreement for the Modified-NUTRIC and SGA severity classification was 46.2%

Acknowledgment

We would like to acknowledge the Mayo Clinic Anesthesia Clinical Research Unit study coordinator Mrs. Nicole Andrijasevic for her help with data extraction.

Sources of Funding Support

This work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) [Grant Number UL1 TR002377]. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors report no relevant conflicts of interests.

Clinical relevancy statement:

Malnutrition is common in critically ill patients and difficult to screen for. Existing screening tools for malnutrition are complex and often rely on unavailable subjective information. We identified a simple objective tool in the Sarcopenia Index that could be used by bedside clinicians to identify and stage patients at high risk for malnutrition.

References

- 1.Lew CCH, Yandell R, Fraser RJL, Chua AP, Chong MFF, Miller M. Association between Malnutrition and Clinical Outcomes in the Intensive Care Unit: A Systematic Review. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2017;41(5):744–758. doi: 10.1177/0148607115625638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lim SL, Ong KCB, Chan YH, Loke WC, Ferguson M, Daniels L. Malnutrition and its impact on cost of hospitalization, length of stay, readmission and 3-year mortality. Clin Nutr. 2012;31(3):345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joint Comission International Accreditation Standards for Hospitals. 6th ed. Oak Brook, IL: Joint Commission Resources; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kubrak C, Jensen L. Malnutrition in acute care patients: a narrative review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44(6):1036–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prado CM, Lieffers JR, McCargar LJ, et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of sarcopenic obesity in patients with solid tumours of the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(7):629–635. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ji Y, Cheng B, Xu Z, et al. Impact of sarcopenic obesity on 30-day mortality in critically ill patients with intra-abdominal sepsis. J Crit Care. 2018;46:50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MAE, Guaitoli PR, Jansma EP, de Vet HCW. Nutrition screening tools: Does one size fit all? A systematic review of screening tools for the hospital setting. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(1):39–58. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel V, Romano M, Corkins MR, et al. Nutrition screening and assessment in hospitalized patients: A survey of current practice in the united states. Nutr Clin Pract. 2014;29(4):483–490. doi: 10.1177/0884533614535446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis CJ, Sowa D, Keim KS, Kinnare K, Peterson S. The use of prealbumin and C-reactive protein for monitoring nutrition support in adult patients receiving enteral nutrition in an urban medical center. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2012. doi: 10.1177/0148607111413896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kashani KBKB, Frazee ENEN, Kukrálová L, et al. Evaluating Muscle Mass by Using Markers of Kidney Function: Development of the Sarcopenia Index. Crit Care Med. 2016;45(4):1–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barreto EF, Poyant JO, Coville HH, et al. Validation of the sarcopenia index to assess muscle mass in the critically ill: A novel application of kidney function markers. Clin Nutr. June 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2018.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kashani K, Al-Khafaji A, Ardiles T, et al. Discovery and validation of cell cycle arrest biomarkers in human acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2013;17(1):R25. doi: 10.1186/cc12503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frazee ENENENEN, Rule AD, Hermann SM, et al. Serum cystatin C predicts vancomycin trough levels better than serum creatinine in hospitalized patients: A cohort study. Crit Care. 2014;18(3):R110. doi: 10.1186/cc13899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frazee E, Rule AD, Lieske JCJC, et al. Cystatin C–Guided Vancomycin Dosing in Critically Ill Patients: A Quality Improvement Project. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(5):658–666. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Jiang X, Day AG. Identifying critically ill patients who benefit the most from nutrition therapy: the development and initial validation of a novel risk assessment tool. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):R268. doi: 10.1186/cc10546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rahman A, Hasan RM, Agarwala R, Martin C, Day AG, Heyland DK. Identifying critically-ill patients who will benefit most from nutritional therapy: Further validation of the “modified NUTRIC” nutritional risk assessment tool. Clin Nutr. 2016;35(1):158–162. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Detsky AS, McLaughlin JR et al. “What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status?” JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1987:8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mueller C, Compher C, Ellen DM. A.S.P.E.N. clinical guidelines: Nutrition screening, assessment, and intervention in adults. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2011;35(1):16–24. doi: 10.1177/0148607110389335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White JV, Guenter P, Jensen G, et al. Consensus statement of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics/American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition: characteristics recommended for the identification and documentation of adult malnutrition (undernutrition). J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112(5):730–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Earthman CP. Body Composition Tools for Assessment of Adult Malnutrition at the Bedside: A Tutorial on Research Considerations and Clinical Applications. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2015;39(7):787–822. doi: 10.1177/0148607115595227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen GL, Cederholm T, Correia MITD, et al. GLIM Criteria for the Diagnosis of Malnutrition: A Consensus Report From the Global Clinical Nutrition Community. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2018;0(0):1–9. doi: 10.1002/jpen.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alberda C, Gramlich L, Jones N, et al. The relationship between nutritional intake and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: Results of an international multicenter observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1567-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McClave SA, Taylor BE, Martindale RG, et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2016;40(2):159–211. doi: 10.1177/0148607115621863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raguso CA, Dupertuis YM, Pichard C. The role of visceral proteins in the nutritional assessment of intensive care unit patients. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2003. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200303000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jie B, Jiang Z-M, Nolan MT, Zhu S-N, Yu K, Kondrup J. Impact of preoperative nutritional support on clinical outcome in abdominal surgical patients at nutritional risk. Nutrition. 2012;28(10):1022–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kashani K, Sarvottam K, Pereira NL, Barreto EF, Kennedy CC. The Sarcopenia Index: a Novel Measure of Muscle Mass in Lung Transplant Candidates. Clin Transplant. December 2017. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He Q, Jiang J, Xie L, Zhang L, Yang M. A sarcopenia index based on serum creatinine and cystatin C cannot accurately detect either low muscle mass or sarcopenia in urban community-dwelling older people. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):11534. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-29808-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levey A, Inker L. Assessment of Glomerular Filtration Rate in Health and Disease: A State of the Art Review. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102(3):405–419. doi: 10.1002/cpt.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nejat M, Pickering JW, Walker RJ, Endre ZH. Rapid detection of acute kidney injury by plasma cystatin C in the intensive care unit. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(10):3283–3289. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfq176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ravn B, Prowle JR, Mårtensson J, Martling C-R, Bell M. Superiority of Serum Cystatin C Over Creatinine in Prediction of Long-Term Prognosis at Discharge From ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(9):1. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Digvijay K, Neri M, Fan W, Ricci Z, Ronco C. International Survey on the Management of Acute Kidney Injury and Continuous Renal Replacement Therapies: Year 2018. Blood Purif. September 2018:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000493724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shlipak MG, Mattes MD, Peralta CA. Update on cystatin C: Incorporation into clinical practice. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(3):595–603. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]