Summary

Microglia play a key role in innate immunity in Alzheimer disease (AD), but their role as antigen-presenting cells is as yet unclear. Here we found that amyloid β peptide (Aβ)-specific T helper 1 (Aβ-Th1 cells) T cells polarized to secrete interferon-γ and intracerebroventricularly (ICV) injected to the 5XFAD mouse model of AD induced the differentiation of major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII)+ microglia with distinct morphology and enhanced plaque clearance capacity than MHCII− microglia. Notably, 5XFAD mice lacking MHCII exhibited an enhanced amyloid pathology in the brain along with exacerbated innate inflammation and reduced phagocytic capacity. Using a bone marrow chimera mouse model, we showed that infiltrating macrophages did not differentiate to MHCII+ cells following ICV injection of Aβ-Th1 cells and did not support T cell-mediated amyloid clearance. Overall, we demonstrate that CD4 T cells induce a P2ry12+ MHCII+ subset of microglia, which play a key role in T cell-mediated effector functions that abrogate AD-like pathology.

Subject Areas: Biological Sciences, Neuroscience, Immunology, Cell Biology

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

ICV-injected Aβ-Th1 T cells elevate MHCII+ microglial cells around plaques

-

•

T cells undergo stimulation by microglia and facilitate amyloid clearance

-

•

Microglia-T cell interactions orchestrate immune mechanisms regulating AD pathology

Biological Sciences; Neuroscience; Immunology; Cell Biology

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease and the primary cause of dementia (Giannakopoulos et al., 2003). The robust synaptic and neuronal loss in the hippocampal and cortical areas of the brain is accompanied by the accumulation of misfolded proteins, such as the amyloid β peptide (Aβ), and by neurofibrillary tangles in affected sites in the parenchyma and vasculature of the brain (Iqbal et al., 2016, Orr et al., 2017, Selkoe and Hardy, 2016). Together, these changes appear to be neurotoxic and cause chronic innate inflammation (Andreasson et al., 2016, Heneka et al., 2015, Van Eldik et al., 2016, Wyss-Coray and Rogers, 2012, Zotova et al., 2010). Innate inflammation in the brain is characterized primarily as a glial activation process, in which both astrocytes and microglia accumulate around amyloid plaques and, thereby, exhibit activated and dysfunctional phenotypes that further increase neurotoxicity (Block et al., 2007, Serrano-Pozo et al., 2011). Whether adaptive immunity mediated by CD4 T cells plays a key role in the inflammatory process in the brain and can be therapeutically used to abrogate the disease is still a matter of debate.

CD4 T cells play a key role in immune regulation and can substantially impact neuroinflammatory processes in the central nervous system (CNS), such as those observed in multiple sclerosis (Hoppmann et al., 2015, Peeters et al., 2017), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (Chiu et al., 2008), and Parkinson disease (Mosley and Gendelman, 2017, Sulzer et al., 2017). The infiltration of CD4 T cells into the brain can be destructive (Anderson et al., 2014, Walsh et al., 2014), but, depending on the neuroinflammatory process and the phenotypes of these T cells, they can also limit neuronal damage caused by infection (Russo and McGavern, 2015), stroke (Liesz et al., 2009), or neurodegenerative diseases (Bryson and Lynch, 2016). Studies in people with AD (Monsonego et al., 2003, Parachikova et al., 2007, Togo et al., 2002, Zota et al., 2009) and in mouse models of the disease (Baek et al., 2016, Baruch et al., 2015, Baruch et al., 2016, Dansokho et al., 2016) suggest that certain CD4 lymphocyte subsets can markedly impact the disease process. We previously showed that whereas peripheral Aβ immunization can cause meningoencephalitis (Monsonego et al., 2006), intracerebroventricularly (ICV)-injected T helper 1 (Th1) T cells can target Aβ plaques in the brain parenchyma and, thereby, locally impact the neuroinflammatory niche to enhance Aβ clearance and reduce innate inflammation, with no evidence of neurotoxic inflammation (Fisher et al., 2014). Notably, these effects of the T cells were mostly brain antigen specific and were not observed to the same extent with ICV-injected ovalbumin (OVA)-specific Th1 T cells (Fisher et al., 2014). Overall, these studies demonstrate that peripheral CD4 T cells can migrate into the brain and locally exert effector functions, which impact the progression of AD, possibly due to local interactions with major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII)-expressing cells.

The expression of MHCII in the brain is low under homeostatic conditions, whereas it can be upregulated in microglia following brain infection or trauma, or over the course of neurodegenerative diseases (McGeer et al., 1987, Schetters et al., 2017, Streit et al., 1999). In people with AD, MHCII expression was found to be upregulated by microglia at sites of Aβ plaques (McGeer et al., 1987, Parachikova et al., 2007). Studies in mice have shown that microglia can differentiate to functional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (Ebner et al., 2013, Gottfried-Blackmore et al., 2009, Monsonego and Weiner, 2003, Wlodarczyk et al., 2015), and two recent single-cell RNA sequencing studies have shown subsets of microglia that appear in the course of neurodegeneration and potentially function as APCs (Keren-Shaul et al., 2017, Mathys et al., 2017). Although MHCII-expressing microglia emerge during neurodegeneration, their functional role as T-cell-stimulating APCs over the course of AD is as yet unclear.

Here, to determine the role of brain APCs in promoting the effector functions of T cells within the brain parenchyma, we ICV-injected Aβ-specific T cells to 5XFAD mice that lack MHCII-expressing cells, either entirely or only in the brain.

Results

ICV Injection of Aβ-specific Th1 Cells to 5XFAD Mice Decreases Aβ Plaques, Which Is Associated with Increased Expression of MHCII by Parenchymal APCs

Using the APP/PS1 mouse model of AD, we have previously demonstrated that whereas T cell activation, but not antigen specificity, was required for ICV-injected T cells to migrate into the brain parenchyma, the induction of MHCII+ cells was more pronounced with Aβ- than with OVA-specific T cells (Fisher et al., 2014). We thus first examined whether ICV-injected Aβ-specific T helper 1 (Aβ-Th1) cells induce the expression of MHCII in the brain of the 5XFAD mouse model of AD. To this end, we generated GFP-expressing Aβ-Th1 cells by immunizing 2-month-old C57BL6 wild-type (WT) mice with Aβ1–42, followed by in vitro expansion, polarization, and a GFP-encoding retrovirus transduction of Aβ-Th1 cells (Figure S1 and Transparent Methods). Next, the GFP+ Aβ-Th1 cells underwent anti-CD3/anti-CD28 dynabeads activation and was ICV-injected (Figure 1A) to 9-month-old WT female mice (Th1→WT) or to 5XFAD female mice (Th1→AD), which accumulate amyloid plaques in the brain by age 2 months (Oakley et al., 2006). As control groups, age- and sex-matched WT and 5XFAD mice were ICV-injected with PBS (PBS→AD). Mice were killed at 11 or 21 days post-injection (dpi) and their brains were excised and analyzed with immunohistochemistry (IHC) and real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR). We found that the ICV-injected GFP+ T cells migrated into the brain parenchyma and that a portion of the cells accumulated at the vicinity of Aβ plaques (11 dpi, Figure 1B). Similar to our results in a previous study (Fisher et al., 2014), the amyloid burden in the brain of 9-month-old 5XFAD mice killed at 21 dpi was significantly reduced in the cortex of Th1→AD mice, when compared with PBS→AD mice (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

ICV Injection of Aβ-Th1 Cells to 5XFAD Mice Decreases Aβ Plaques in the Brain Associated with Increased Expression of MHCII by Parenchymal APCs

Aβ-Th1 T cells were generated following the Aβ1–42 immunization of 2-month-old mice (Transparent Methods and Figure S1A). 5XFAD mice were ICV-injected with either Aβ-Th1 T cells or PBS, killed at 11 or 21 days post-injection (dpi), and their brains collected and analyzed by IHC or qPCR.

(A) Illustration of a representative coronal view of the adult mouse brain and the injection site in the lateral ventricle.

(B) A representative IHC image (left) of Aβ plaques co-localized with GFP+ T cells (green) in brain sections derived from 5XFAD mice 11 dpi of activated Aβ-Th1 cells. Sections were immunolabeled with anti-Aβ (red) and a DAPI nucleus counterstain (blue). The middle image is a higher magnification of the framed area, showing the interaction between Aβ and Aβ-Th1 T cells. The right image is a 3D reconstruction of z-sections (9.75 μm overall, 0.75 μm/slice) of the framed area. Scale bars, 200 μm (left), 50 μm (middle), and 5 μm (right).

(C) Representative IHC images showing Aβ plaque load in brain sections derived from 5XFAD mice ICV-injected with either PBS (PBS→AD, left) or Aβ-Th1 T cells (Th1→AD, right). Sections were taken at 21 dpi (n = 4–5 mice per group) and immunolabeled with anti-Aβ plaques (red) and a DAPI nucleus counterstain (blue). Scale bars, 200 μm. The quantitative analysis of the Aβ plaque load in the cortex (right graph) was performed with IMARIS and shows the mean ± SEM results of one experiment out of four performed.

(D) Representative IHC images showing the upregulation of MHCII+ cells in brain sections derived from either PBS→AD (left) or Th1→AD (right) mice at 21 dpi (n = 6 mice per group), immunolabeled with anti-MHCII (green), anti-Aβ (red), and a DAPI nucleus counterstain (blue). The higher magnifications of the framed areas reveal MHCII+ cells accumulating near the Aβ plaques. Scale bars, 200 μm in the low-magnification images and 50 μm in the high-magnification images. The quantitative analysis of the number of MHCII+ cells per volume of cortical section (right graph) was performed with IMARIS. Each symbol represents an individual mouse, whereas the horizontal lines indicate the mean ± SEM of one experiment out of four performed.

(E) qPCR analysis of CD74 expression in the cortex (left) and hippocampus (right) of Th1→AD and PBS→AD mice at 21 dpi (n = 6–7 mice per group). Bars represent means ± SEM.

(F) Representative IHC images demonstrating an immunological synapse between MHCII+ cells and GFP+ T cells in brain sections derived from Th1→AD mice at 11 dpi (n = 5 mice) and immunolabeled with anti-phalloidin (cytoskeletal marker, blue), anti-MHCII (red), and GFP T cells (top images), or with anti-Zap70 (phospho Tyr 319) (red), anti-MHCII (blue), GFP T cells, and a DAPI nucleus counterstain (gray) (bottom images). In the top images, the middle and right panels are 3D reconstructions of z-sections (11.25 μm overall, 0.75 μm/slice). Scale bars, 10 μm. In the bottom images, the middle and right images are a 3D reconstruction of z-sections (7 μm overall, 0.5 μm/slice), which was then sliced in the xy axis. The front orientation of the xy-sliced 3D reconstruction shows an immunological synapse via Zap70 (phospho Tyr 319) (right). Scale bars, 10 μm (left) and 5 μm (middle and right images). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 ((C and D) Student's t test and (E) one-way ANOVA).

Next, we determined whether the enhanced clearance of Aβ in Th1→AD mice is associated with increased numbers of MHCII+ cells in the brain parenchyma. Notably, IHC analysis showed a significant increase in MHCII+ cells in close proximity to Aβ plaques, in the cortex (Figure 1D) of Th1→AD mice, but not in PBS→AD mice, and an upregulation of the invariant chain CD74 mRNA, which was analyzed using qPCR (Figure 1E). Brain sections immunolabeled with anti-MHCII and with either the cytoskeletal marker phalloidin, which labels F-actin (Figure 1F, upper panels), or anti-phospho-Zap70 (Zeta-chain-associated protein kinase 70), a protein kinase required for T cell activation (Figure 1F, lower panels), demonstrate the polarization of GFP+ T cells toward MHCII+ cells in the cortex and their activation, as indicated by Zap70 phosphorylation.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that the ICV-injected T cells upregulate MHCII by certain microglial subsets or infiltrating macrophages, which, in turn, appear to generate an immunological synapse with the injected T cells.

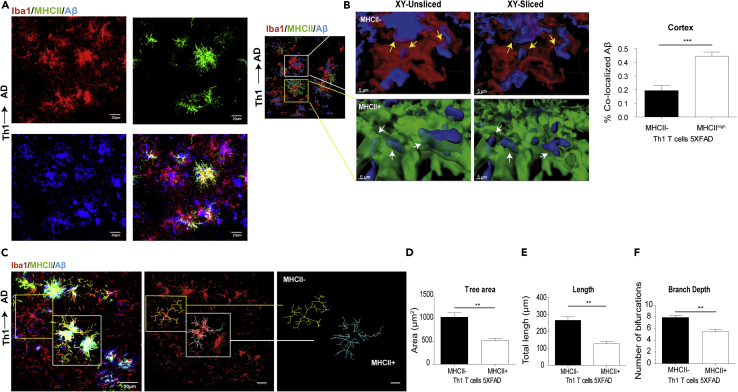

MHCII+ Cells Are More Phagocytic and less Ramified Than MHCII− Cells in 5XFAD Mice ICV-Injected with Aβ-Th1 Cells

Microglial accumulation around amyloid plaques is one of the classical hallmarks of AD. We and others have shown that, once recruited to plaques, microglia undergo morphological changes, such as increased soma size and thickened processes, which represent their activation state or their dysfunctional properties (Andreasson et al., 2016, Davies et al., 2017, Spittau, 2017, Walker and Lue, 2015). To test whether the MHCII+ cells are morphologically distinct from MHCII− cells and impact the phagocytic capacity of Aβ in the brain, we prepared sagittal brain sections from Th1→AD mice. The sections were immunolabeled for Iba1, MHCII, and Aβ, and the proportion of Aβ localized to MHCII+ cells was analyzed with the IMARIS software. A co-labeling IHC analysis revealed that MHCII+ cells primarily colocalize with IbaI+ and Aβ at the vicinity of plaque (Figure 2A). To determine whether the MHCII+ cells phagocytose Aβ, the 3D reconstructed images were sliced in the xy plane using a clipping tool in IMARIS. The unsliced panels (Figure 2B; left, upper, and lower panels) show the interactions of MHCII+ and MHCII− cells with Aβ, whereas the xy-sliced panels (Figure 2B; right, upper, and lower panels) demonstrate Aβ engulfed by the cells. A quantitative analysis demonstrated that the MHCII+ cells co-localized with Aβ more efficiently than with MHCII− cells (Figure 2B), thus presumably indicating an upregulation of phagocytic activity.

Figure 2.

MHCII+ Cells Are More Phagocytic and Less Ramified than MHCII− Cells in 5XFAD Mice ICV-Injected with Aβ-Th1 Cells

5XFAD mice were ICV-injected with either Aβ-Th1 T cells or PBS, killed at 21 dpi, and their brains collected and analyzed by IHC.

(A) Representative IHC images showing the accumulation of Iba1+ and MHCII + cells at the vicinity of plaque in brain sections derived from Th1→AD mice at 21 dpi and immunolabeled with anti-Iba1 (red), anti-MHCII (green), and anti-Aβ (blue). The rightmost lower panel shows the merged image.

(B) The left image is a 3D reconstruction of z-sections (17.25 μm overall, 0.75 μm/slice), demonstrating the co-localization of Aβ with MHCII− and MHCII+ cells. The images in the middle are higher magnifications of the framed areas, showing MHCII− (top) and MHCII+ (bottom) cells. The images on the right are xy plane slices of the 3D reconstructions. Scale bars, 30 μm (left image) and 5 μm (middle and right images). The yellow and white arrows indicate the co-localization of Aβ with MHCII− and MHCII+ cells, respectively. A quantitative analysis (right graph) of the percentage of Aβ that was co-localized with MHCII− or MHCII + cells in the cortex was conducted with IMARIS. Bars represent means ± SEM.

(C) Representative IHC images showing the backbone of single cells (yellow and white frames indicate MHCII− and MHCII + cells, respectively), traced manually with the IMARIS Filament Tracer plug-in (middle and right images).

(D–F) Quantitative morphometric analyses of randomly selected MHCII+ and MHCII− cortical microglia (layer 2 or 3), performed with IMARIS and statistically analyzed with GraphPad. Bars represent the means ± SEM of the total tree area (D), total branch length (E), and branch depth (F) in one experiment out of four performed (n = 5 mice per group). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (Student's t test).

To morphologically characterize MHCII+ and MHCII− cells, confocal z stacks were captured and the images were manually traced by the backbone of the cells, using the IMARIS Filament Tracer plug-in. The tree area, total branch length, and number of bifurcations were calculated with IMARIS. We found that, whereas MHCII− microglia show the typical ramified morphology, the MHCII+ cells that surround the plaques exhibit a more amoeboid-like morphology with an enlarged soma size (Figure 2C). A manual 3D reconstruction of MHCII− and MHCII+ cells is shown in Figure 2C. Quantitative analyses of the reconstructed images show that MHCII+ Iba1+ cells exhibit a decrease in the spatial coverage area (Figure 2D), process length (Figure 2E), and process bifurcation (Figure 2F), when compared with MHCII− Iba1+ cells. This finding suggests that the MHCII+ Iba1+ subset of cells, which expands in 5XFAD mice upon an ICV injection of Aβ-specific Th1 cells, may represent a beneficial response in the brain by reducing plaque burden.

MHCII-Knockout 5XFAD Mice Exhibit an Exacerbated Amyloid Pathology

MHCII expression by myeloid cells is essential for the selection and activation of CD4 T cells, a process that may facilitate the overall uptake of Aβ in the brain. Therefore, we backcrossed 5XFAD mice onto MHCII-knockout (KO) background mice to generate 5XFAD mice that lack MHCII (5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice). Age-matched littermates were used as WT and 5XFAD control groups (Figures 3A and S2). Then we characterized the inflammatory reaction in the brain and the accumulation of Aβ plaques in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− and 5XFAD mice at 1, 3, and 6 months age. Brain sections were first immunolabeled with anti-Aβ, and the volume occupied by Aβ plaques in the cortex was calculated using IMARIS. Surprisingly, and despite the use of an aggressive model of amyloidosis, we found that Aβ accumulated in the brain by 1 month age in 5XFAD/MHCII−/−, whereas almost no plaques were observed in 5XFAD mice (Figure 3B). Furthermore, at older ages, the volume of Aβ plaques in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice was nearly 2-fold higher than in 5XFAD mice (Figure 3B). To determine whether gene expression indicating inflammatory reaction in the brain was similarly upregulated in 5XFAD and 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice, we used qPCR. A significant upregulation of mRNAs encoding interleukin (IL)-1β and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) was found in 5XFAD and in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice, when compared with littermate control mice, both at 3 and 6 months of age (Figure 3C). The mRNA levels of IL-6 and interferon (IFN)-γ were not upregulated in either 5XFAD or 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice at 3 months of age, whereas they were significantly upregulated in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice at 6 months of age, when compared with either 5XFAD or littermate control mice (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

MHCII-Knockout 5XFAD Mice Exhibit An Exacerbated Amyloid Pathology

Immune-deficient 5XFAD mice lacking MHCII (5XFAD/MHCII−/−) were generated, and their plaque pathology, neuroinflammation, and phagocytic clearance were characterized. 5XFAD/MHCII−/− and age-matched 5XFAD mice (n = 4–5 mice per group) were killed at 1, 3, or 6 months of age, and their brain samples were analyzed by IHC or qPCR.

(A) A breeding diagram of the strategy used to generate 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice.

(B) Representative IHC images showing Aβ plaque pathology at 1, 3, and 6 months of age in brain sections derived from 5XFAD and 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice and immunolabeled for anti-Aβ (red) and a DAPI nucleus counterstain (blue). Quantitative analyses of the Aβ plaque load per volume of cortical section (right graphs) were performed with IMARIS. Each symbol represents one mouse, and the bars represent means ± SEM.

(C) A qPCR analysis of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and IFN-γ and the astrogliosis marker GFAP in the brains of 3- (top panels) and 6-month-old (bottom panels) 5XFAD mice, 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice, and littermate control mice. Bars represent means ± SEM.

(D) The 3D reconstructions (left images) of z-sections (21 μm overall, 0.75 μm/slice) in cortical sections. The images to the right are higher magnifications of the framed areas, showing the co-localization of Aβ with Iba1+ cells (unsliced and sliced) in brain sections of 5XFAD (top panels) and 5XFAD/MHCII−/− (bottom panels) mice. Scale bars, 30 μm (left images) and 5 μm (all other images). The quantitative analysis (right graph) of the percentage of Aβ co-localized with Iba1+ microglia in the cortex was performed with IMARIS. Bars represent means ± SEM.

(E) A qPCR analysis of the phagocytic markers TREM2 and SIRP-1β in the cortex of 3- and 6-month-old mice. Bars represent means ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 ((B and D) Student's t test, (C and E) one-way ANOVA).

To determine whether the increase in plaque pathology observed in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice was due to a reduced clearance of Aβ in the brain, we used high-resolution confocal microscopy and 3D image reconstruction. Brain sections from 6-month-old 5XFAD/MHCII−/− and 5XFAD mice were immunolabeled for Aβ and Iba1 and the proportion of Aβ engulfed by activated microglia was analyzed. Notably, the 3D reconstruction of the IHC image showed that whereas Iba1+ cells penetrated the plaques in 5XFAD mice, they were primarily in the plaque vicinity in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice (Figure 3D). Furthermore, the 3D reconstructed image was sliced in the xy axis using IMARIS, demonstrating Aβ engulfed by the Iba1+ cells. A quantitative analysis of the fraction of Aβ co-localized with microglia was significantly lower in brain sections of 5XFAD/MHCII−/− (0.26% ± 0.06%) than in those of 5XFAD mice (0.54% ± 0.06%) (Figure 3D). Immunolabeling for Aβ, Iba1, and the lysosome marker CD68 revealed a marked decrease in Iba1+ CD68+ cells co-localized with Aβ plaques in the brain of 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice (Figure S3). In addition, the qPCR analysis demonstrated a decrease in the mRNA levels of the phagocytic markers TREM-2 and SIRP-1β in the brain of 5XFAD/MHCII−/−, when compared with those in the brain of 5XFAD mice, which was significant for both genes at 6 months of age, and only for SIRP-1β at 3 months of age (Figure 3E). Taken together, these results indicate that, in the absence of MHCII, the phagocytic capacity of microglia in the brain is reduced; this is accompanied by a dysregulation of the inflammatory reaction in the brain and an exacerbated Aβ pathology.

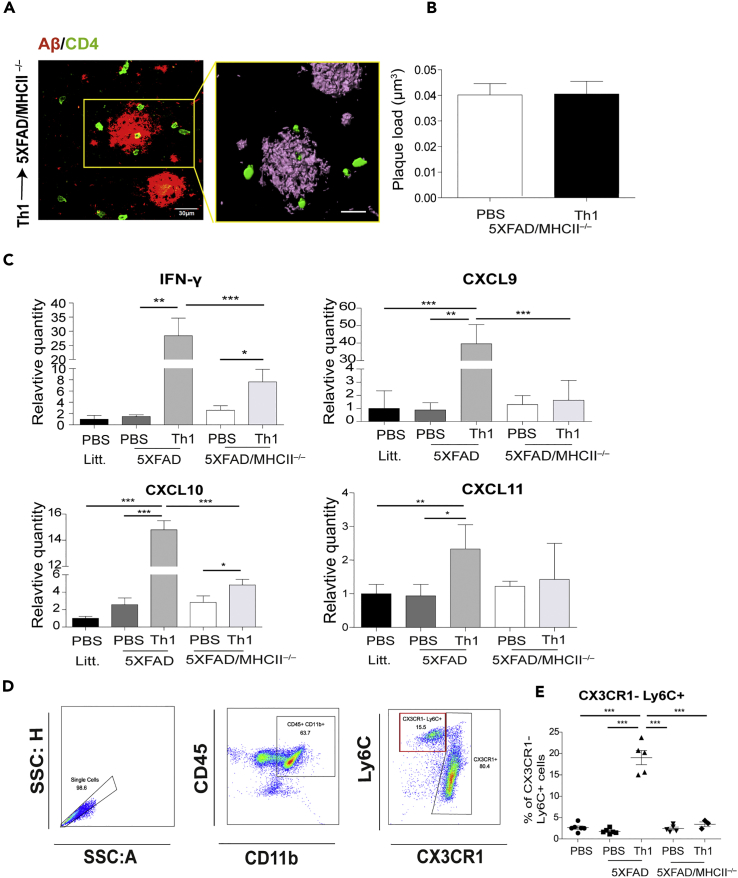

ICV-Injected Aβ-Th1 Cells Exhibit Reduced Effector Functions in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− Mice

To determine whether the exacerbated pathology observed in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice can be recovered by using activated CD4 T cells, we subjected Aβ-Th1 cells to polyclonal activation with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 dynabeads and ICV-injected them to 7-month-old 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice and to 5XFAD mice. Mice were killed at 21 dpi, a time required to determine T cell effector functions induced by brain APCs, and their brains were analyzed for the presence of CD4 T cells, Aβ plaque load, and inflammatory mediators. Surprisingly, IHC analysis of the cortex revealed that although the CD4 T cells migrated into the brain of 5XFAD/MHCII−/−, no differences in plaque load were observed, when compared with mice ICV-injected with PBS (Figures 4A and 4B). Furthermore, the qPCR analysis showed that the mRNAs encoding the Th1 cytokine IFN-γ and the chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, which are ligands of the CXCR3 receptor on Th1 T cells, were only slightly upregulated in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice ICV-injected with Th1 cells, when compared with 5XFAD mice ICV-injected with Th1 cells (Figure 4C). In light of these observations, we sought to determine whether the reduced clearance of Aβ in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice ICV-injected with Aβ-Th1 cells is due to a reduced monocyte infiltration into the brain. To test this hypothesis, brain cells were isolated enzymatically from all the groups of mice at 21 dpi and analyzed with flow cytometry. Single cells were gated for CD45+ CD11b+ myeloid cells, which were then analyzed for putative infiltrating CX3CR1−Ly6C+ macrophages (Figure 4D). CX3CR1−Ly6C+ cells were indeed observed in the brain of 5XFAD mice that had been ICV-injected with Aβ-Th1 cells; however, this phenomenon was observed neither in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice ICV-injected with Aβ-Th1 cells nor in the respective PBS-injected control groups (Figures 4E and S4).

Figure 4.

ICV-Injected Aβ-Th1 Cells Exhibit Reduced Effector Functions in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− Mice

5XFAD and 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice were ICV-injected with either Aβ-Th1 T cells or PBS (n = 4–5 mice per group), killed at 21 dpi, and their brains collected and analyzed with IHC, qPCR, or flow cytometry.

(A) Representative IHC images showing Aβ plaques co-localized with GFP+ T cells in brain sections derived from 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice at 21 dpi and immunolabeled with anti-Aβ (red) and anti-CD4 (green). The right image is a 3D reconstruction of z-sections (22.5 μm overall, 0.75 μm/slice) of the framed area. Scale bars, 30 μm (left) and 10 μm (right).

(B) The quantitative analysis (right graph) of Aβ plaque load per volume of the cortical section in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice ICV-injected with either PBS or Th1 T cells (right) was performed with IMARIS. Bars represent means ± SEM.

(C) qPCR analysis of IFN-γ and the chemokines CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 in the different groups of mice. Bars represent means ± SEM.

(D) Flow cytometry plots demonstrating the gating strategy for myeloid cells (CD45+ CD11b+; middle) and presumed infiltrated macrophages (Ly6C+ CX3CR1−; right).

(E) The frequency of CX3CR1−Ly6C+ cells in all groups. Bars represent means ± SEM of one experiment out of two performed. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA).

Taken together, these results indicate that MHCII expression by microglia or infiltrating macrophages results in the stimulation of T cells, which consequently impacts the inflammatory milieu and Aβ accumulation.

Microglial Expression of MHCII Is Required to Stimulate the Effector Functions of ICV-Injected Aβ-Th1 Cells within the Brain Parenchyma

The ICV injection of Aβ-Th1 cells to 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice did not result in T cell activation within the brain and, therefore, the T cells did not significantly impact the immune milieu or reduce the plaque load in the brain (Figure 4). However, these findings do not indicate whether the re-stimulation of the ICV-injected Aβ-Th1 cells in the brain of 5XFAD mice is mediated by peripheral APCs or, alternatively, by APCs within the brain parenchyma. To answer this question, we generated WTGFP/GFP→5XFAD/MHCII−/− bone marrow (BM) chimera (BMC) mice in which MHCII+ BM is transplanted to 5XFAD/MHCII−/− (Transparent Methods). Of the 12 mice that received BM transplants, six were injected with Aβ-Th1 cells 8 weeks after the BM transplantation. Then, at 28 dpi, the mice were killed and perfused and their brains were excised and analyzed using both IHC and flow cytometry. As expected, the IHC analysis revealed enhanced infiltration of GFP+ BM-derived cells in BMC mice that were ICV-injected with Aβ-Th1 cells, when compared with untreated BM-transplanted mice (Figure 5A); however, the accumulation of the infiltrating GFP+ BM-derived cells around A β plaques remained similar in both groups (Figure 5B). Next, we determined the Aβ pathology of BMC mice that were either ICV-injected or not injected with Aβ-Th1 cells and compared it with the pathology of untreated 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice. An IHC analysis of the amyloid burden in the cortex of BMC mice revealed that, when compared with untreated 5XFAD/MHCII−/−mice, the plaque volume was significantly reduced (Figure 5C). Regardless of the enhanced infiltration of GFP+ BM-derived cells into the brains of 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice ICV-injected with Aβ-Th1 cells (Figure 5A), no further reduction in Aβ was observed in these mice, when compared with the non-injected BMC mice (Figure 5C). Notably, the GFP+ macrophages infiltrating into the brain parenchyma were mostly detected as MHCII− cells in BMC mice that were either ICV-injected or not injected with T cells (Figure 5D).

Figure 5.

Microglial Expression of MHCII Is Required to Stimulate the Effector Functions of ICV-Injected Aβ-Th1 Cells within the Brain Parenchyma

Bone marrow chimera (BMC) mice (n = 12) were generated, and after 8 weeks, six of them were ICV-injected with Aβ-Th1 T cells, whereas the other six were left untreated. The mice were perfused at 28 dpi, and their brains were excised and analyzed by IHC and flow cytometry.

(A) Representative IHC images of cortical (top images) and hippocampal (bottom images) brain sections from untreated BMC mice (left) and from BMC mice that were ICV-injected with Aβ-Th1 T cells (Th1→BMC, right) (n = 5 mice per group) and immunolabeled with DAPI nucleus counterstain (blue). Green cells are infiltrating macrophages. A quantitative analysis (right graphs) of the number of GFP+ cells per volume of cortical or hippocampal section was performed with IMARIS. Scale bars, 200 μm. Bars represent means ± SEM, and each symbol represents an individual mouse.

(B) Representative IHC image showing Aβ plaques co-localized with infiltrated GFP+ BM cells in brain sections derived from either BMC or Aβ-Th1→BMC mice and immunolabeled with the DAPI nucleus counterstain (blue) (n = 5 mice per group). Scale bars, 200 μm (left images) and 30 μm (right images).

(C) Representative IHC image showing Aβ plaque load in brain sections derived from untreated (UT), BMC, or Aβ-Th1→BMC mice and immunolabeled with anti-Aβ (gray) and a DAPI nucleus counterstain (blue). The quantitative analysis (right graph) of the plaque load per volume of cortical section was performed with IMARIS. Scale bars, 200 μm. Bars represent means ± SEM.

(D) Representative IHC images of brain sections derived from untreated BMC mice (top images) or from Aβ-Th1→BMC mice (bottom images) and immunolabeled with anti-MHCII (blue) and a DAPI nucleus counterstain (gray). Green cells represent infiltrating BM cells. Scale bars, 30 μm. ***p < 0.001 [(A) Student's t-test, (C) one-way ANOVA].

The results shown in Figure 5 suggest that the MHCII+ cells observed in 5XFAD mice ICV-injected with Aβ-Th1 cells are primarily brain-endogenous microglia. To determine that microglia can indeed give rise to MHCII+ cells, 8- or 9-month-old 5XFAD mice were ICV-injected with Aβ-Th1 cells and their brains were subjected to flow cytometry analysis at 21 dpi. Single cells were first gated for the CD45+ CD11b+ cells, and the gated cells were then plotted with the MHCII and Ly6C myeloid markers (Figures 6A−6C). The fraction of MHCII+ cells out of the CD45+ CD11b+ cells was then analyzed for all groups (PBS→ littermates, PBS→ 5XFAD, and Th1→ 5XFAD), revealing a significant increase in MHCII+ cells in the brain parenchyma of mice ICV-injected with Aβ-Th1 cells (9.79% ± 1.29%), when compared with mice ICV-injected with PBS (3.95% ± 0.39%) (Figure 6B). MHCII+ cells from each group were then plotted for the Ly6C marker, which revealed 28.16% ± 0.77% and 63.56% ± 5.13% cells within the presumed infiltrating CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6Chigh macrophages and brain-endogenous CD45+ CD11b+ Ly6Clow microglia, respectively (Figure 6C). Next, we conducted an RNAscope fluorescence in situ hybridization at 14 dpi to identify the MHCII+ cells in the brains of 5XFAD mice ICV-injected with Aβ-Th1 cells. P2ry12 and CD74 were used as markers of endogenous microglia (Butovsky et al., 2014, Zhu et al., 2017) and MHCII+ cells, respectively. Ppib (peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase B) was used as a positive control (Figure 6D). These analyses revealed that CD74 mRNA (yellow arrows) is expressed primarily in microglia cells expressing the P2ry12 mRNA (white arrows) (Figure 6E). Note that not all P2ry12-expressing microglia express CD74 and that, as expected, some cells are negative to both markers (pink arrow). Overall, these data suggest that the MHCII+ cells, which were observed in 5XFAD mice and with increased frequencies in 5XFAD mice ICV-injected with Aβ-Th1 cells, are primarily endogenous microglia.

Figure 6.

Aβ-Th1 T Cells Upregulate MHCII Expression in Brain Endogenous Microglia of 5XFAD Mice

5XFAD and littermate (litt.) control mice were ICV-injected with either Aβ-Th1 T cells or PBS, killed at 14 or 21 dpi, and their brains excised and analyzed by using RNAscope (14 dpi) or flow cytometry (21 dpi).

(A) Flow cytometry plots demonstrating the gating strategy from single cells (left) to myeloid cells (CD45+ CD11b+; right).

(B) Flow cytometry plots demonstrating MHCII+ cells (out of CD11b+ CD45+ cells) in PBS→litt mice (left), PBS→5XFAD mice (middle), and Th1→5XFAD mice (right). The frequency of MHCII+ cells was quantified for all groups (right graph). Each symbol represents an individual mouse (n = 5 mice per group), and the bars represent means ± SEM of one experiment out of four performed.

(C) Flow cytometry plots demonstrating Ly6C+ cells (out of MHCII+ CD11b+ CD45+ cells) in the above-mentioned groups. The frequency of Ly6C+ cells was quantified for all groups (right graph). Each symbol represents an individual mouse (n = 5 per group), and the bars represent means ± SEM.

(D) Representative RNAscope fluorescence in situ hybridization images showing the co-expression of CD74 (red), P2ry12 (green) mRNA, and a DAPI nucleus counterstain (blue) in brain sections derived from Aβ-Th1→5XFAD mice (n = 5). Representative images of positive Ppib (green) and negative controls. Each puncta indicates a single mRNA molecule. The rectangular box demonstrates higher magnification of the framed area.

(E) A representative image showing P2ry12- (green) and CD74- (red) expressing cells. A higher magnification merge image of the framed area (top right panel) and the single-channel images (lower panels) show P2ry12+ (white arrows), P2ry12− (pink arrows), and CD74+ (yellow arrows) cells. Scale bars, 50 and 10 μm. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA).

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to test whether T cells can promote the differentiation of myeloid cells in the brain parenchyma into APCs with enhanced Aβ uptake capacity. We demonstrate that Aβ-Th1 cells, ICV-injected to 5XFAD mice, not only migrate into the brain parenchyma but also stimulate the expansion of MHCII+ cells. This process is associated with the activation of T cells, the modulation of the inflammatory reaction to Aβ pathology, and enhancement of Aβ uptake. We found that the newly differentiated MHCII+ cells originate primarily from brain-endogenous microglia. As such, this subset of MHCII+ microglia may serve to target therapeutic antigen-specific T cells directly to damaged sites within the CNS.

We have previously shown that Aβ-specific T cells polarized to Th1 T cells and ICV-injected to APP/PS1 mice transmigrate into the brain parenchyma, where they impact the inflammatory response induced by Aβ and enhance amyloid plaque uptake (Fisher et al., 2014). However, it was unclear whether these T cells undergo reactivation by APCs within the brain parenchyma in a manner that stimulates their effector functions. Here, we found that MHCII+ cells expand in the brain parenchyma following an ICV injection of Aβ-Th1 cells. Moreover, we show that these MHCII+ cells accumulate in the vicinity of Aβ plaques and exhibit a less ramified morphology and enhanced phagocytic capacity, when compared with Iba+ microglia. Finally, we found that the MHCII+ cells interact with the injected T cells in a manner reminiscent of an immunological synapse, which is essential for T cell activation. Taken together, our findings suggest that, within the brain parenchyma, brain-infiltrating Aβ-Th1 cells can stimulate the differentiation and expansion of MHCII+ cells, whose phagocytic and antigen presentation capacity is considerably greater than those of MHCII− microglia.

Although MHCII in activated microglia is known to be upregulated at the vicinity of plaques in brains of people with AD (Hopperton et al., 2018, Parachikova et al., 2007, Schetters et al., 2017, Tooyama et al., 1990) and in mouse models of the disease (Landel et al., 2014, Mathys et al., 2017), it remains unclear whether MHCII expression by microglia or infiltrating macrophages plays a role in the progression of AD. Surprisingly, we found that 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice, which lack MHCII, exhibit a worsened amyloid pathology compared with 5XFAD mice, and that this pathology is accompanied by an enhanced innate inflammation. Furthermore, the Aβ phagocytic capacity of microglia in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice was significantly reduced and the mRNA expression of SIRP-β1 and TREM2—two genes that play important roles in the activation and phagocytic machinery of microglia and macrophages in the brain (Finelli et al., 2015, Gaikwad et al., 2009, Hickman and El Khoury, 2014, Rivest, 2015, Zhang et al., 2015)—was downregulated. Notably, in contrast to SIRP-β1, TREM2 was significantly upregulated in 5XFAD mice (Keren-Shaul et al., 2017, Wang et al., 2015, Wang et al., 2016) and was slightly downregulated in 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice. These results suggest that CD4 T cell effector functions are required to effectively stimulate the phagocytic capacity of microglia within the brain, a mechanism that may involve not only the upregulation of phagocytic molecules but also the downregulation of inhibitory receptors such as LILRB1 (Barkal et al., 2018). In line with these findings, a recent study demonstrated that Aβ uptake is reduced in a Rag-5XFAD mouse model of AD, which lacks the entire cellular and humoral adaptive arms of the immune system, and that IgG treatment enhances the uptake of Aβ in these mice (Marsh et al., 2016). Overall, it is suggested that both humoral and cellular immune responses—orchestrated by CD4 T cells—play a significant role in the capacity of the brain to clear Aβ.

Another important finding in this study was that, although we activated the Aβ-Th1 cells before their ICV injection, they exhibited significantly reduced effector functions (as indicated by the reduced mRNA levels of IFN-γ and CXCL9/10/11 chemokines and by the significantly reduced number of presumed infiltrating macrophages) in the brains of 5XFAD/MHCII−/− mice, when compared with 5XFAD mice. These findings suggest that the effector functions of the ICV-injected Aβ-Th1 cells are facilitated by antigen presentation in the brain. It, however, remained unclear whether this T cell re-stimulation is mediated by brain-endogenous microglia or by peripheral macrophages. Generating a WTGFP/GFP→ 5XFAD/MHCII−/− BMC mice, we recovered the leukocyte repertoire and turnover of the meningeal macrophages to MHCII+ cells, and thus, except for some infiltrating GFP+ cells, microglia in the brain of the BMC mice remained MHCII−. Notably, whereas recovering the peripheral and meningeal leukocytes in the BMC mice reduced the amyloid load in the brain, the ICV-injected cells did not facilitate this reduction. These results strongly suggest that brain-endogenous MHCII+ microglia are required to re-stimulate the T cells. In line with our findings, a subset of MHCII+ microglia was recently observed in a mouse model of neurodegeneration and was suggested to be a type-II IFN-induced subset of microglia, which may potentially function as APCs (Mathys et al., 2017). In addition, this subset is highly similar to disease-associated microglia, a subset that was recently reported in the 5XFAD mouse model of AD (Keren-Shaul et al., 2017). More recently, a subset of MHCII+ microglia was observed within activated response microglia (ARMs) in a mouse model of AD (Sala Frigerio et al., 2019). Interestingly, ARMs were more frequent in female than in male mice (Sala Frigerio et al., 2019), suggesting a gender variation in microglial phenotypes (Nelson et al., 2017, VanRyzin et al., 2019), which may affect their activation profile in aging and disease. Taking together, a relatively low frequency of MHCII+ microglia accumulate in the brain during inflammation, a phenomenon that calls for further research to explore their origin, molecular characteristics, differentiation program, and functional properties.

Several studies previously reported a CD11c+ subset of microglia that accumulates in the CNS during neuroinflammation, and that is significantly different from CD11c− microglia (Kamphuis et al., 2016, Monsonego and Weiner, 2003, Re et al., 2002, Wlodarczyk et al., 2015). Thus it is possible that the higher levels of IFN-γ found in the brain following the ICV injection of Aβ-Th1 cells in our study further promote the expansion and differentiation of this subset to functional APCs. Indeed, using the RNAscope technique to co-label the mRNAs of the invariant chain CD74 and of the microglial marker P2ry12, we determined that the MHCII+ subset that accumulated at the plaque vicinity derives from brain-endogenous microglia. Our in vivo study thus strongly suggests that parenchymal microglia can function as APCs, and that this function is required to stimulate the ICV-injected T cells in 5XFAD mice.

Overall, our study suggests that the function of microglia as APCs plays an important role in brain immunity, which, based on the T cell phenotype (Th1, Th2, Th17, or regulatory T cells [Tregs]), can exert either beneficial or neurotoxic responses. We have previously shown that the Th1 subset of cells is the most effective subset in preconditioning the brain for T cell migration, primarily due to IFN-γ being the key cytokine that these T cells secrete (Fisher et al., 2014). Hence, IFN-γ appears to be required to promote the differentiation of certain subsets of microglia to APCs, which thereby acquire an enhanced phagocytic capacity (Fisher et al., 2014, Gottfried-Blackmore et al., 2009, Monsonego and Weiner, 2003), as well as to promote the various neuroprotective functions observed in animal models, such as in the induction of IL-6 expression in astrocytes during acute neuroinflammation (Sun et al., 2017), the induction of IL-10 after spinal cord injury (Ishii et al., 2013), and the induction of neurogenesis (Mastrangelo et al., 2009). The Th1 cells may be only the first arrivals into the brain, paving the way for regulatory T cells such as Th2/Tr1 or Foxp3+ Tregs, which were found to be important for immune regulation in mouse models of neurodegenerative diseases (Baruch et al., 2015, Kipnis et al., 2004, Mayo et al., 2016, Ochi et al., 2008, Perdigoto et al., 2015). It cannot be excluded, though, that leukocytes such as CD8 T cells (Lassmann, 2018, Lassmann and Bradl, 2017), natural killer cells, and neutrophils (Cruz Hernandez et al., 2019) may also infiltrate the brain and cause neurotoxicity. It is thus intriguing to examine whether the dysregulated CD4 T cells that are observed with aging (Harpaz et al., 2017, Moro-Garcia et al., 2013, Nikolich-Zugich, 2018) fail to properly regulate adaptive immunity in the brain and, therefore, facilitate neurotoxic inflammation and the progression of AD. This process of immune senescence may also explain why immunotherapies suitable for adults are not always effective for elderly individuals. Further characterizing immune senescence processes and their impact on neurotoxic inflammation may thus pave the way toward therapeutic approaches that target peripheral immune senescence, thus allowing a proper dialog between brain-infiltrating CD4 T cells and MHCII-expressing microglia, which may be required to promote neural repair in the AD brain.

Limitations of the Study

-

1.

qPCR was used in the current study to analyze the expression of inflammatory genes in the brain. As some of these markers were not measured at the protein level, they represent transcriptional changes that do not necessarily define the proinflammatory phenotype of the cells.

-

2.

Our experimental setup was based on ICV—rather than intravenous—injection of T cells, a process that may cause acute microglial activation and hence a relatively robust differentiation of microglial subsets to APCs.

Methods

All methods can be found in the accompanying Transparent Methods supplemental file.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ram Gal for his valuable comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (# 684/14) and the Litwin and Gural Foundations.

Author Contributions

K.M. designed the study, performed and analyzed experiments, and drafted the manuscript. E.E., O.B., Y.E., D.A., I. Strominger, and I. Spiegel., performed and analyzed experiments. A.N. contributed technical expertise. A.M. designed and supervised the study and wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests. The corresponding author has a patent entitled “T-cell therapy to neurodegenerative diseases.”

Published: June 28, 2019

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2019.05.039.

Supplemental Information

References

- Anderson K.M., Olson K.E., Estes K.A., Flanagan K., Gendelman H.E., Mosley R.L. Dual destructive and protective roles of adaptive immunity in neurodegenerative disorders. Transl. Neurodegener. 2014;3:25. doi: 10.1186/2047-9158-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Anderson, K.M., Olson, K.E., Estes, K.A., Flanagan, K., Gendelman, H.E., and Mosley, R.L. (2014). Dual destructive and protective roles of adaptive immunity in neurodegenerative disorders. Transl. Neurodegener. 3, 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Andreasson K.I., Bachstetter A.D., Colonna M., Ginhoux F., Holmes C., Lamb B., Landreth G., Lee D.C., Low D., Lynch M.A. Targeting innate immunity for neurodegenerative disorders of the central nervous system. J. Neurochem. 2016;138:653–693. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Andreasson, K.I., Bachstetter, A.D., Colonna, M., Ginhoux, F., Holmes, C., Lamb, B., Landreth, G., Lee, D.C., Low, D., Lynch, M.A., et al. (2016). Targeting innate immunity for neurodegenerative disorders of the central nervous system. J. Neurochem. 138, 653-693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baek H., Ye M., Kang G.H., Lee C., Lee G., Choi D.B., Jung J., Kim H., Lee S., Kim J.S. Neuroprotective effects of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in a 3xTg-AD Alzheimer's disease model. Oncotarget. 2016;7:69347–69357. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Baek, H., Ye, M., Kang, G.H., Lee, C., Lee, G., Choi, D.B., Jung, J., Kim, H., Lee, S., Kim, J.S., et al. (2016). Neuroprotective effects of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in a 3xTg-AD Alzheimer's disease model. Oncotarget 7, 69347-69357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Barkal A.A., Weiskopf K., Kao K.S., Gordon S.R., Rosental B., Yiu Y.Y., George B.M., Markovic M., Ring N.G., Tsai J.M. Engagement of MHC class I by the inhibitory receptor LILRB1 suppresses macrophages and is a target of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:76–84. doi: 10.1038/s41590-017-0004-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Barkal, A.A., Weiskopf, K., Kao, K.S., Gordon, S.R., Rosental, B., Yiu, Y.Y., George, B.M., Markovic, M., Ring, N.G., Tsai, J.M., et al. (2018). Engagement of MHC class I by the inhibitory receptor LILRB1 suppresses macrophages and is a target of cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Immunol. 19, 76-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baruch K., Deczkowska A., Rosenzweig N., Tsitsou-Kampeli A., Sharif A.M., Matcovitch-Natan O., Kertser A., David E., Amit I., Schwartz M. PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade reduces pathology and improves memory in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Med. 2016;22:135–137. doi: 10.1038/nm.4022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Baruch, K., Deczkowska, A., Rosenzweig, N., Tsitsou-Kampeli, A., Sharif, A.M., Matcovitch-Natan, O., Kertser, A., David, E., Amit, I., and Schwartz, M. (2016). PD-1 immune checkpoint blockade reduces pathology and improves memory in mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Med. 22, 135-137. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Baruch K., Rosenzweig N., Kertser A., Deczkowska A., Sharif A.M., Spinrad A., Tsitsou-Kampeli A., Sarel A., Cahalon L., Schwartz M. Breaking immune tolerance by targeting Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells mitigates Alzheimer's disease pathology. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7967. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Baruch, K., Rosenzweig, N., Kertser, A., Deczkowska, A., Sharif, A.M., Spinrad, A., Tsitsou-Kampeli, A., Sarel, A., Cahalon, L., and Schwartz, M. (2015). Breaking immune tolerance by targeting Foxp3(+) regulatory T cells mitigates Alzheimer's disease pathology. Nat. Commun. 6, 7967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Block M.L., Zecca L., Hong J.S. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Block, M.L., Zecca, L., and Hong, J.S. (2007). Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 57-69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bryson K.J., Lynch M.A. Linking T cells to Alzheimer's disease: from neurodegeneration to neurorepair. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2016;26:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bryson, K.J., and Lynch, M.A. (2016). Linking T cells to Alzheimer's disease: from neurodegeneration to neurorepair. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 26, 67-73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Butovsky O., Jedrychowski M.P., Moore C.S., Cialic R., Lanser A.J., Gabriely G., Koeglsperger T., Dake B., Wu P.M., Doykan C.E. Identification of a unique TGF-beta-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat. Neurosci. 2014;17:131–143. doi: 10.1038/nn.3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Butovsky, O., Jedrychowski, M.P., Moore, C.S., Cialic, R., Lanser, A.J., Gabriely, G., Koeglsperger, T., Dake, B., Wu, P.M., Doykan, C.E., et al. (2014). Identification of a unique TGF-beta-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nat. Neurosci. 17, 131-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chiu I.M., Chen A., Zheng Y., Kosaras B., Tsiftsoglou S.A., Vartanian T.K., Brown R.H., Jr., Carroll M.C. T lymphocytes potentiate endogenous neuroprotective inflammation in a mouse model of ALS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2008;105:17913–17918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804610105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chiu, I.M., Chen, A., Zheng, Y., Kosaras, B., Tsiftsoglou, S.A., Vartanian, T.K., Brown, R.H., Jr., and Carroll, M.C. (2008). T lymphocytes potentiate endogenous neuroprotective inflammation in a mouse model of ALS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 105, 17913-17918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cruz Hernandez J.C., Bracko O., Kersbergen C.J., Muse V., Haft-Javaherian M., Berg M., Park L., Vinarcsik L.K., Ivasyk I., Rivera D.A. Neutrophil adhesion in brain capillaries reduces cortical blood flow and impairs memory function in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Nat. Neurosci. 2019;22:413–420. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0329-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cruz Hernandez, J.C., Bracko, O., Kersbergen, C.J., Muse, V., Haft-Javaherian, M., Berg, M., Park, L., Vinarcsik, L.K., Ivasyk, I., Rivera, D.A., et al. (2019). Neutrophil adhesion in brain capillaries reduces cortical blood flow and impairs memory function in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 413-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dansokho C., Ait Ahmed D., Aid S., Toly-Ndour C., Chaigneau T., Calle V., Cagnard N., Holzenberger M., Piaggio E., Aucouturier P. Regulatory T cells delay disease progression in Alzheimer-like pathology. Brain. 2016;139:1237–1251. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dansokho, C., Ait Ahmed, D., Aid, S., Toly-Ndour, C., Chaigneau, T., Calle, V., Cagnard, N., Holzenberger, M., Piaggio, E., Aucouturier, P., et al. (2016). Regulatory T cells delay disease progression in Alzheimer-like pathology. Brain 139, 1237-1251. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Davies D.S., Ma J., Jegathees T., Goldsbury C. Microglia show altered morphology and reduced arborization in human brain during aging and Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol. 2017;27:795–808. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Davies, D.S., Ma, J., Jegathees, T., and Goldsbury, C. (2017). Microglia show altered morphology and reduced arborization in human brain during aging and Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol. 27, 795-808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ebner F., Brandt C., Thiele P., Richter D., Schliesser U., Siffrin V., Schueler J., Stubbe T., Ellinghaus A., Meisel C. Microglial activation milieu controls regulatory T cell responses. J. Immunol. 2013;191:5594–5602. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ebner, F., Brandt, C., Thiele, P., Richter, D., Schliesser, U., Siffrin, V., Schueler, J., Stubbe, T., Ellinghaus, A., Meisel, C., et al. (2013). Microglial activation milieu controls regulatory T cell responses. J. Immunol. 191, 5594-5602. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Finelli D., Rollinson S., Harris J., Jones M., Richardson A., Gerhard A., Snowden J., Mann D., Pickering-Brown S. TREM2 analysis and increased risk of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2015;36 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.08.001. e549–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Finelli, D., Rollinson, S., Harris, J., Jones, M., Richardson, A., Gerhard, A., Snowden, J., Mann, D., and Pickering-Brown, S. (2015). TREM2 analysis and increased risk of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 36, e549-513. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fisher Y., Strominger I., Biton S., Nemirovsky A., Baron R., Monsonego A. Th1 polarization of T cells injected into the cerebrospinal fluid induces brain immunosurveillance. J. Immunol. 2014;192:92–102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Fisher, Y., Strominger, I., Biton, S., Nemirovsky, A., Baron, R., and Monsonego, A. (2014). Th1 polarization of T cells injected into the cerebrospinal fluid induces brain immunosurveillance. J. Immunol. 192, 92-102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gaikwad S., Larionov S., Wang Y., Dannenberg H., Matozaki T., Monsonego A., Thal D.R., Neumann H. Signal regulatory protein-beta1: a microglial modulator of phagocytosis in Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;175:2528–2539. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gaikwad, S., Larionov, S., Wang, Y., Dannenberg, H., Matozaki, T., Monsonego, A., Thal, D.R., and Neumann, H. (2009). Signal regulatory protein-beta1: a microglial modulator of phagocytosis in Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 175, 2528-2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Giannakopoulos P., Herrmann F.R., Bussiere T., Bouras C., Kovari E., Perl D.P., Morrison J.H., Gold G., Hof P.R. Tangle and neuron numbers, but not amyloid load, predict cognitive status in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2003;60:1495–1500. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000063311.58879.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Giannakopoulos, P., Herrmann, F.R., Bussiere, T., Bouras, C., Kovari, E., Perl, D.P., Morrison, J.H., Gold, G., and Hof, P.R. (2003). Tangle and neuron numbers, but not amyloid load, predict cognitive status in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 60, 1495-1500. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gottfried-Blackmore A., Kaunzner U.W., Idoyaga J., Felger J.C., McEwen B.S., Bulloch K. Acute in vivo exposure to interferon-gamma enables resident brain dendritic cells to become effective antigen presenting cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2009;106:20918–20923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911509106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Gottfried-Blackmore, A., Kaunzner, U.W., Idoyaga, J., Felger, J.C., McEwen, B.S., and Bulloch, K. (2009). Acute in vivo exposure to interferon-gamma enables resident brain dendritic cells to become effective antigen presenting cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 106, 20918-20923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Harpaz I., Bhattacharya U., Elyahu Y., Strominger I., Monsonego A. Old mice accumulate activated effector CD4 T cells refractory to regulatory T cell-induced immunosuppression. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:283. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Harpaz, I., Bhattacharya, U., Elyahu, Y., Strominger, I., and Monsonego, A. (2017). Old Mice Accumulate Activated Effector CD4 T Cells Refractory to Regulatory T Cell-Induced Immunosuppression. Front. Immunol. 8, 283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Heneka M.T., Carson M.J., Khoury J.E., Landreth G.E., Brosseron F., Feinstein D.L., Jacobs A.H., Wyss-Coray T., Vitorica J., Ransohoff R.M. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:388–405. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Heneka, M.T., Carson, M.J., Khoury, J.E., Landreth, G.E., Brosseron, F., Feinstein, D.L., Jacobs, A.H., Wyss-Coray, T., Vitorica, J., Ransohoff, R.M., et al. (2015). Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 14, 388-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hickman S.E., El Khoury J. TREM2 and the neuroimmunology of Alzheimer's disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014;88:495–498. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hickman, S.E., and El Khoury, J. (2014). TREM2 and the neuroimmunology of Alzheimer's disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 88, 495-498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hopperton K.E., Mohammad D., Trepanier M.O., Giuliano V., Bazinet R.P. Markers of microglia in post-mortem brain samples from patients with Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. Mol. Psychiatry. 2018;23:177–198. doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hopperton, K.E., Mohammad, D., Trepanier, M.O., Giuliano, V., and Bazinet, R.P. (2018). Markers of microglia in post-mortem brain samples from patients with Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 177-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hoppmann N., Graetz C., Paterka M., Poisa-Beiro L., Larochelle C., Hasan M., Lill C.M., Zipp F., Siffrin V. New candidates for CD4 T cell pathogenicity in experimental neuroinflammation and multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2015;138:902–917. doi: 10.1093/brain/awu408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Hoppmann, N., Graetz, C., Paterka, M., Poisa-Beiro, L., Larochelle, C., Hasan, M., Lill, C.M., Zipp, F., and Siffrin, V. (2015). New candidates for CD4 T cell pathogenicity in experimental neuroinflammation and multiple sclerosis. Brain 138, 902-917. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Iqbal K., Liu F., Gong C.X. Tau and neurodegenerative disease: the story so far. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2016;12:15–27. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Iqbal, K., Liu, F., and Gong, C.X. (2016). Tau and neurodegenerative disease: the story so far. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 12, 15-27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ishii H., Tanabe S., Ueno M., Kubo T., Kayama H., Serada S., Fujimoto M., Takeda K., Naka T., Yamashita T. ifn-gamma-dependent secretion of IL-10 from Th1 cells and microglia/macrophages contributes to functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e710. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ishii, H., Tanabe, S., Ueno, M., Kubo, T., Kayama, H., Serada, S., Fujimoto, M., Takeda, K., Naka, T., and Yamashita, T. (2013). ifn-gamma-dependent secretion of IL-10 from Th1 cells and microglia/macrophages contributes to functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Cell Death Dis. 4, e710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kamphuis W., Kooijman L., Schetters S., Orre M., Hol E.M. Transcriptional profiling of CD11c-positive microglia accumulating around amyloid plaques in a mouse model for Alzheimer's disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1862:1847–1860. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kamphuis, W., Kooijman, L., Schetters, S., Orre, M., and Hol, E.M. (2016). Transcriptional profiling of CD11c-positive microglia accumulating around amyloid plaques in a mouse model for Alzheimer's disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1862, 1847-1860. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Keren-Shaul H., Spinrad A., Weiner A., Matcovitch-Natan O., Dvir-Szternfeld R., Ulland T.K., David E., Baruch K., Lara-Astaiso D., Toth B. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer's disease. Cell. 2017;169:1276–1290.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Keren-Shaul, H., Spinrad, A., Weiner, A., Matcovitch-Natan, O., Dvir-Szternfeld, R., Ulland, T.K., David, E., Baruch, K., Lara-Astaiso, D., Toth, B., et al. (2017). A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer's disease. Cell 169, 1276-1290.e17. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kipnis J., Avidan H., Caspi R.R., Schwartz M. Dual effect of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in neurodegeneration: a dialogue with microglia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004;101(Suppl 2):14663–14669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404842101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Kipnis, J., Avidan, H., Caspi, R.R., and Schwartz, M. (2004). Dual effect of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in neurodegeneration: a dialogue with microglia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 101 Suppl 2, 14663-14669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Landel V., Baranger K., Virard I., Loriod B., Khrestchatisky M., Rivera S., Benech P., Feron F. Temporal gene profiling of the 5XFAD transgenic mouse model highlights the importance of microglial activation in Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2014;9:33. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Landel, V., Baranger, K., Virard, I., Loriod, B., Khrestchatisky, M., Rivera, S., Benech, P., and Feron, F. (2014). Temporal gene profiling of the 5XFAD transgenic mouse model highlights the importance of microglial activation in Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 9, 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lassmann H. Pathogenic mechanisms associated with different clinical courses of multiple sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 2018;9:3116. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lassmann, H. (2018). Pathogenic mechanisms associated with different clinical courses of multiple sclerosis. Front. Immunol. 9, 3116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lassmann H., Bradl M. Multiple sclerosis: experimental models and reality. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;133:223–244. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1631-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lassmann, H., and Bradl, M. (2017). Multiple sclerosis: experimental models and reality. Acta Neuropathol. 133, 223-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Liesz A., Suri-Payer E., Veltkamp C., Doerr H., Sommer C., Rivest S., Giese T., Veltkamp R. Regulatory T cells are key cerebroprotective immunomodulators in acute experimental stroke. Nat. Med. 2009;15:192–199. doi: 10.1038/nm.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Liesz, A., Suri-Payer, E., Veltkamp, C., Doerr, H., Sommer, C., Rivest, S., Giese, T., and Veltkamp, R. (2009). Regulatory T cells are key cerebroprotective immunomodulators in acute experimental stroke. Nat. Med. 15, 192-199. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marsh S.E., Abud E.M., Lakatos A., Karimzadeh A., Yeung S.T., Davtyan H., Fote G.M., Lau L., Weinger J.G., Lane T.E. The adaptive immune system restrains Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis by modulating microglial function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2016;113:E1316–E1325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525466113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Marsh, S.E., Abud, E.M., Lakatos, A., Karimzadeh, A., Yeung, S.T., Davtyan, H., Fote, G.M., Lau, L., Weinger, J.G., Lane, T.E., et al. (2016). The adaptive immune system restrains Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis by modulating microglial function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 113, E1316-1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mastrangelo M.A., Sudol K.L., Narrow W.C., Bowers W.J. Interferon-{gamma} differentially affects Alzheimer's disease pathologies and induces neurogenesis in triple transgenic-AD mice. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;175:2076–2088. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mastrangelo, M.A., Sudol, K.L., Narrow, W.C., and Bowers, W.J. (2009). Interferon-{gamma} differentially affects Alzheimer's disease pathologies and induces neurogenesis in triple transgenic-AD mice. Am. J. Pathol. 175, 2076-2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mathys H., Adaikkan C., Gao F., Young J.Z., Manet E., Hemberg M., De Jager P.L., Ransohoff R.M., Regev A., Tsai L.H. Temporal tracking of microglia activation in neurodegeneration at single-cell resolution. Cell Rep. 2017;21:366–380. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mathys, H., Adaikkan, C., Gao, F., Young, J.Z., Manet, E., Hemberg, M., De Jager, P.L., Ransohoff, R.M., Regev, A., and Tsai, L.H. (2017). Temporal tracking of microglia activation in neurodegeneration at single-cell resolution. Cell Rep. 21, 366-380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mayo L., Cunha A.P., Madi A., Beynon V., Yang Z., Alvarez J.I., Prat A., Sobel R.A., Kobzik L., Lassmann H. IL-10-dependent Tr1 cells attenuate astrocyte activation and ameliorate chronic central nervous system inflammation. Brain. 2016;139:1939–1957. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mayo, L., Cunha, A.P., Madi, A., Beynon, V., Yang, Z., Alvarez, J.I., Prat, A., Sobel, R.A., Kobzik, L., Lassmann, H., et al. (2016). IL-10-dependent Tr1 cells attenuate astrocyte activation and ameliorate chronic central nervous system inflammation. Brain 139, 1939-1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McGeer P.L., Itagaki S., Tago H., McGeer E.G. Reactive microglia in patients with senile dementia of the Alzheimer type are positive for the histocompatibility glycoprotein HLA-DR. Neurosci. Lett. 1987;79:195–200. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(87)90696-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; McGeer, P.L., Itagaki, S., Tago, H., and McGeer, E.G. (1987). Reactive microglia in patients with senile dementia of the Alzheimer type are positive for the histocompatibility glycoprotein HLA-DR. Neurosci. Lett. 79, 195-200. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Monsonego A., Imitola J., Petrovic S., Zota V., Nemirovsky A., Baron R., Fisher Y., Owens T., Weiner H.L. Abeta-induced meningoencephalitis is IFN-gamma-dependent and is associated with T cell-dependent clearance of Abeta in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:5048–5053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506209103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Monsonego, A., Imitola, J., Petrovic, S., Zota, V., Nemirovsky, A., Baron, R., Fisher, Y., Owens, T., and Weiner, H.L. (2006). Abeta-induced meningoencephalitis is IFN-gamma-dependent and is associated with T cell-dependent clearance of Abeta in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 103, 5048-5053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Monsonego A., Weiner H.L. Immunotherapeutic approaches to Alzheimer's disease. Science. 2003;302:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1088469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Monsonego, A., and Weiner, H.L. (2003). Immunotherapeutic approaches to Alzheimer's disease. Science 302, 834-838. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Monsonego A., Zota V., Karni A., Krieger J.I., Bar-Or A., Bitan G., Budson A.E., Sperling R., Selkoe D.J., Weiner H.L. Increased T cell reactivity to amyloid beta protein in older humans and patients with Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:415–422. doi: 10.1172/JCI18104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Monsonego, A., Zota, V., Karni, A., Krieger, J.I., Bar-Or, A., Bitan, G., Budson, A.E., Sperling, R., Selkoe, D.J., and Weiner, H.L. (2003). Increased T cell reactivity to amyloid beta protein in older humans and patients with Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 415-422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Moro-Garcia M.A., Alonso-Arias R., Lopez-Larrea C. When aging reaches CD4+ T-Cells: phenotypic and functional changes. Front. Immunol. 2013;4:107. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Moro-Garcia, M.A., Alonso-Arias, R., and Lopez-Larrea, C. (2013). When aging reaches CD4+ T-Cells: phenotypic and functional changes. Front. Immunol. 4, 107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mosley R.L., Gendelman H.E. T cells and Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16:769–771. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mosley, R.L., and Gendelman, H.E. (2017). T cells and Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 16, 769-771. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nelson L.H., Warden S., Lenz K.M. Sex differences in microglial phagocytosis in the neonatal hippocampus. Brain Behav. Immun. 2017;64:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Nelson, L.H., Warden, S., and Lenz, K.M. (2017). Sex differences in microglial phagocytosis in the neonatal hippocampus. Brain Behav. Immun. 64, 11-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nikolich-Zugich J. The twilight of immunity: emerging concepts in aging of the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 2018;19:10–19. doi: 10.1038/s41590-017-0006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Nikolich-Zugich, J. (2018). The twilight of immunity: emerging concepts in aging of the immune system. Nat. Immunol. 19, 10-19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Oakley H., Cole S.L., Logan S., Maus E., Shao P., Craft J., Guillozet-Bongaarts A., Ohno M., Disterhoft J., Van Eldik L. Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer's disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:10129–10140. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1202-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Oakley, H., Cole, S.L., Logan, S., Maus, E., Shao, P., Craft, J., Guillozet-Bongaarts, A., Ohno, M., Disterhoft, J., Van Eldik, L., et al. (2006). Intraneuronal beta-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer's disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J. Neurosci. 26, 10129-10140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ochi H., Abraham M., Ishikawa H., Frenkel D., Yang K., Basso A., Wu H., Chen M.L., Gandhi R., Miller A. New immunosuppressive approaches: oral administration of CD3-specific antibody to treat autoimmunity. J. Neurol. Sci. 2008;274:9–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ochi, H., Abraham, M., Ishikawa, H., Frenkel, D., Yang, K., Basso, A., Wu, H., Chen, M.L., Gandhi, R., Miller, A., et al. (2008). New immunosuppressive approaches: oral administration of CD3-specific antibody to treat autoimmunity. J. Neurol. Sci. 274, 9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Orr M.E., Sullivan A.C., Frost B. A brief overview of tauopathy: causes, consequences, and therapeutic strategies. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017;38:637–648. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Orr, M.E., Sullivan, A.C., and Frost, B. (2017). A Brief Overview of Tauopathy: Causes, Consequences, and Therapeutic Strategies. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 38, 637-648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Parachikova A., Agadjanyan M.G., Cribbs D.H., Blurton-Jones M., Perreau V., Rogers J., Beach T.G., Cotman C.W. Inflammatory changes parallel the early stages of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2007;28:1821–1833. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Parachikova, A., Agadjanyan, M.G., Cribbs, D.H., Blurton-Jones, M., Perreau, V., Rogers, J., Beach, T.G., and Cotman, C.W. (2007). Inflammatory changes parallel the early stages of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol. Aging 28, 1821-1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Peeters L.M., Vanheusden M., Somers V., Van Wijmeersch B., Stinissen P., Broux B., Hellings N. Cytotoxic CD4+ T cells drive multiple sclerosis progression. Front. Immunol. 2017;8:1160. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Peeters, L.M., Vanheusden, M., Somers, V., Van Wijmeersch, B., Stinissen, P., Broux, B., and Hellings, N. (2017). Cytotoxic CD4+ T cells drive multiple sclerosis progression. Front. Immunol. 8, 1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Perdigoto A.L., Chatenoud L., Bluestone J.A., Herold K.C. Inducing and administering tregs to treat human disease. Front. Immunol. 2015;6:654. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Perdigoto, A.L., Chatenoud, L., Bluestone, J.A., and Herold, K.C. (2015). Inducing and administering tregs to treat human disease. Front. Immunol. 6, 654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Re F., Belyanskaya S.L., Riese R.J., Cipriani B., Fischer F.R., Granucci F., Ricciardi-Castagnoli P., Brosnan C., Stern L.J., Strominger J.L. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces an expression program in Neonatal Microglia that primes them for antigen presentation. J. Immunol. 2002;169:2264–2273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Re, F., Belyanskaya, S.L., Riese, R.J., Cipriani, B., Fischer, F.R., Granucci, F., Ricciardi-Castagnoli, P., Brosnan, C., Stern, L.J., Strominger, J.L., et al. (2002). Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor induces an expression program in Neonatal Microglia That primes them for antigen presentation. J. Immunol. 169, 2264-2273. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rivest S. TREM2 enables amyloid beta clearance by microglia. Cell Res. 2015;25:535–536. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Rivest, S. (2015). TREM2 enables amyloid beta clearance by microglia. Cell Res. 25, 535-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Russo M.V., McGavern D.B. Immune surveillance of the CNS following infection and injury. Trends Immunol. 2015;36:637–650. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Russo, M.V., and McGavern, D.B. (2015). Immune Surveillance of the CNS following Infection and Injury. Trends Immunol. 36, 637-650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sala Frigerio C., Wolfs L., Fattorelli N., Thrupp N., Voytyuk I., Schmidt I., Mancuso R., Chen W.T., Woodbury M.E., Srivastava G. The major risk factors for alzheimer's disease: age, sex, and genes modulate the Microglia Response to Abeta plaques. Cell Rep. 2019;27:1293–1306.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.03.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sala Frigerio, C., Wolfs, L., Fattorelli, N., Thrupp, N., Voytyuk, I., Schmidt, I., Mancuso, R., Chen, W.T., Woodbury, M.E., Srivastava, G., et al. (2019). The major risk factors for alzheimer's disease: age, sex, and genes modulate the Microglia Response to Abeta plaques. Cell Rep 27, 1293-1306.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schetters S.T.T., Gomez-Nicola D., Garcia-Vallejo J.J., Van Kooyk Y. Neuroinflammation: microglia and t cells get ready to tango. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1905. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Schetters, S.T.T., Gomez-Nicola, D., Garcia-Vallejo, J.J., and Van Kooyk, Y. (2017). Neuroinflammation: Microglia and t cells get ready to tango. Front Immunol 8, 1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Selkoe D.J., Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016;8:595–608. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Selkoe, D.J., and Hardy, J. (2016). The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol. Med. 8, 595-608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Serrano-Pozo A., Mielke M.L., Gomez-Isla T., Betensky R.A., Growdon J.H., Frosch M.P., Hyman B.T. Reactive glia not only associates with plaques but also parallels tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2011;179:1373–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Serrano-Pozo, A., Mielke, M.L., Gomez-Isla, T., Betensky, R.A., Growdon, J.H., Frosch, M.P., and Hyman, B.T. (2011). Reactive glia not only associates with plaques but also parallels tangles in Alzheimer's disease. Am. J. Pathol. 179, 1373-1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Spittau B. Aging microglia-phenotypes, functions and implications for age-related Neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2017;9:194. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Spittau, B. (2017). Aging microglia-phenotypes, functions and implications for age-related Neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9, 194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Streit W.J., Walter S.A., Pennell N.A. Reactive microgliosis. Prog. Neurobiol. 1999;57:563–581. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Streit, W.J., Walter, S.A., and Pennell, N.A. (1999). Reactive microgliosis. Prog. Neurobiol. 57, 563-581. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sulzer D., Alcalay R.N., Garretti F., Cote L., Kanter E., Agin-Liebes J., Liong C., McMurtrey C., Hildebrand W.H., Mao X. T cells from patients with Parkinson's disease recognize alpha-synuclein peptides. Nature. 2017;546:656–661. doi: 10.1038/nature22815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sulzer, D., Alcalay, R.N., Garretti, F., Cote, L., Kanter, E., Agin-Liebes, J., Liong, C., McMurtrey, C., Hildebrand, W.H., Mao, X., et al. (2017). T cells from patients with Parkinson's disease recognize alpha-synuclein peptides. Nature 546, 656-661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sun L., Li Y., Jia X., Wang Q., Li Y., Hu M., Tian L., Yang J., Xing W., Zhang W. Neuroprotection by IFN-gamma via astrocyte-secreted IL-6 in acute neuroinflammation. Oncotarget. 2017;8:40065–40078. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Sun, L., Li, Y., Jia, X., Wang, Q., Li, Y., Hu, M., Tian, L., Yang, J., Xing, W., Zhang, W., et al. (2017). Neuroprotection by IFN-gamma via astrocyte-secreted IL-6 in acute neuroinflammation. Oncotarget 8, 40065-40078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Togo T., Akiyama H., Iseki E., Kondo H., Ikeda K., Kato M., Oda T., Tsuchiya K., Kosaka K. Occurrence of T cells in the brain of Alzheimer's disease and other neurological diseases. J. Neuroimmunol. 2002;124:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00496-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Togo, T., Akiyama, H., Iseki, E., Kondo, H., Ikeda, K., Kato, M., Oda, T., Tsuchiya, K., and Kosaka, K. (2002). Occurrence of T cells in the brain of Alzheimer's disease and other neurological diseases. J. Neuroimmunol. 124, 83-92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tooyama I., Kimura H., Akiyama H., McGeer P.L. Reactive microglia express class I and class II major histocompatibility complex antigens in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 1990;523:273–280. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91496-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Tooyama, I., Kimura, H., Akiyama, H., and McGeer, P.L. (1990). Reactive microglia express class I and class II major histocompatibility complex antigens in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 523, 273-280. [DOI] [PubMed]