Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of this study was to assess the direct injection of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) suspended in hyaluronic acid (HA) combined with drilling as a treatment for chondral defects in a canine model.

Methods

Tibial bone marrow was aspirated, and BMSCs were isolated and cultured. One 8.0-mm diameter chondral defect was created in the femoral groove, and nine 0.9-mm diameter holes were drilled into the defect. BMSCs (2.14 × 107 cells) suspended in HA were injected into the defect. HA alone was injected into a similar defect on the contralateral knee as a control. Animals were sacrificed at 3 and 6 months.

Results

Although the percentage of coverage assessed macroscopically was significantly better at 6 months than at 3 months in both the BMSC (p = 0.02) and control (p = 0.001) groups, there were no significant differences in the International Cartilage Repair Society grades. The Wakitani histological score was significantly better at 6 months than at 3 months in the BMSC and control groups. While the control defects were mostly filled with fibrocartilage, several of the defects in the BMSC group contained hyaline-like cartilage. The mean Wakitani scores of the BMSC group improved from 7.0 ± 1.0 at 3 months to 4.6 ± 0.9 at 6 months, and those of the control group improved from 9.4 ± 1.2 to 6.0 ± 0.6. The BMSC group showed significantly better regeneration than the control group at 3 months (p = 0.04), but the difference at 6 months was not significant (p = 0.06).

Conclusions

The direct injection of BMSCs in HA combined with drilling enhanced cartilage regeneration.

Keywords: Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell, Direct injection, Chondral defect, Regenerative therapy, Bone marrow stimulation, Hyaluronic acid

Abbreviations: BMSCs, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells; HA, hyaluronic acid; ICRS, International Cartilage Repair Society

Highlights

-

•

Direct injection of BMSCs with HA and drilling was tested for chondral defects.

-

•

HA alone was injected into a similar defect on the contralateral knee as a control.

-

•

Macroscopic coverage and histology indicated better healing at 6 than at 3 months.

-

•

The BMSC group healed significantly better than the control group at 3 months.

1. Introduction

Articular cartilage covers the ends of bones that form diarthrodial joints and functions as a lubricant and shock absorber. Articular cartilage is a histologically hyaline cartilage and contains an abundant extracellular matrix that lacks blood, lymphatic, and nerve supplies. These factors contribute to its poor repair potential. Typically, the reparative tissue generated after an injury lacks the biochemical capability to express certain cartilage-specific molecules and shows a substantially reduced biomechanical durability compared with normal hyaline cartilage [1]. Articular cartilage defects are a major clinical problem. The clinical symptoms or radiological changes caused by articular cartilage defects show progressive worsening over more than 10 years [2], [3]. Therefore, the repair of articular cartilage defects is now thought to be essential for preventing their progression to subsequent osteoarthritis.

Currently, the conventional treatment for articular cartilage defects is a bone marrow stimulation technique, in which the subchondral bone is perforated to facilitate cartilage repair by the bone marrow-derived cells and growth factors present in blood [4]. However, after this procedure, the cartilage defects are most often repaired with fibrocartilage, which is biochemically and biomechanically different from normal hyaline cartilage. Over time, fibrocartilage undergoes degeneration [1]. The benefits of autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) [5] and mosaicplasty [6], [7], [8] have been reported over the last 20 years. Although small articular cartilage defects can be successfully repaired using these techniques, normal cartilage tissue must be harvested for use. Alternative methods for obtaining autologous cells that avoid such tissue harvesting would be preferable.

Investigations into the repair of articular cartilage defects using various types of cells have been performed around the world. Osteochondral progenitor cells and mesenchymal stem cells exist in many kinds of tissue, including bone marrow, synovium, muscle and fat, and autologous cells can be easily obtained from these tissues. Among these cell types, we have previously used bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) as a cell source to assess new methods for enhancing cartilage regeneration involving the transplantation of autologous BMSCs into articular cartilage defects. In 1994, we showed the effectiveness of BMSC transplantation for the repair of osteochondral defects in a preclinical study using the rabbit model [9]. Later, we found that BMSC transplantation into chondral defects in a clinical trial in humans resulted in better and longer-lasting good clinical outcomes [10], [11], [12]. In another study, we compared BMSC transplantation concomitant with high tibial osteotomy (HTO) with HTO alone to determine the efficacy of the BMSCs. Although the BMSC group showed significantly better arthroscopic and histological results than the control group at the 16-month follow-up, the clinical results were not significantly different between the groups [13]. This trend was confirmed at the 5- and 10-year follow-ups [14]. In addition, we examined the records from all 41 patients (45 transplantations) that we treated with this procedure, including the cases mentioned above, from January 1998 to November 2008 until their last visit to the clinic. No tumors or infections were observed during the 5–137 months (mean: 75 months) of follow-up, indicating that autologous BMSC transplantation is safe [15].

However, the techniques used in these basic and clinical studies for BMSC transplantation, as well as ACI, required an arthrotomy to place the stem cells in the defects. Recently, several authors have reported less invasive methods, including intra-articular injections for transplanting stem cells. Such procedures have contributed to the effective regeneration of articular cartilage in animal models [16], [17], [18], [19].

The purpose of the present study was to assess the direct injection of BMSCs suspended in hyaluronic acid (HA) combined with bone marrow stimulation to treat chondral defects compared with treatment with bone marrow stimulation and HA injection alone. Our hypothesis was that injection of BMSCs suspended in HA and bone marrow stimulation leads to better articular cartilage regeneration than bone marrow stimulation and HA alone.

2. Materials and methods

Fifteen male, 1-year-old beagle dogs (mean weight 10.4 (range: 9.8–11.6) kg, Oriental Yeast Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), which were free of musculoskeletal abnormalities, were used in this experiment. The animals were housed in large cages for at least 1 week to acclimatize them to the surroundings, and they were provided food and water ad libitum prior to the experiment. All experimental animal procedures were approved by and conducted in accordance with the regulations of the Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine Committee on Animal Research.

2.1. Harvest of BMSC and culture

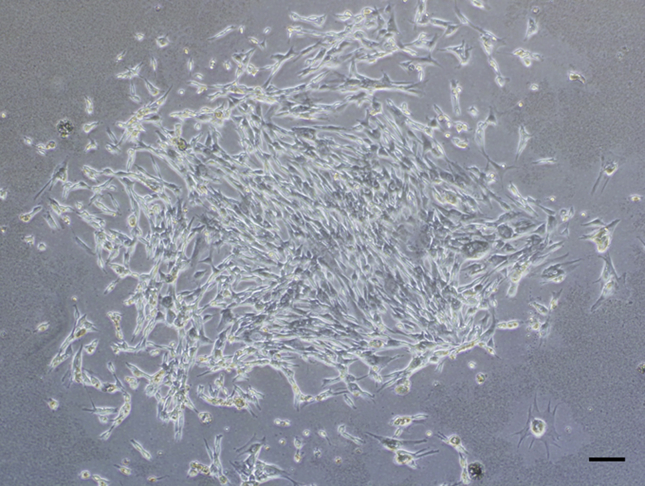

Under anesthesia induced by subcutaneous injection of ketamine (50 mg/mL; Sankyo, Tokyo, Japan) and xylazine (0.2 mg/mL; Bayer HealthCare, Tokyo, Japan) at a ratio of 10:3 and a dose of 0.5 mL/kg body weight, 5 mL of bone marrow was aspirated from the tibia using a bone marrow harvesting needle (SHEEN MAN Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) that was attached to a syringe containing 0.2 mL of heparin (1000 units/mL). The aspirates were washed with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd, Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (Gibco Lab Inc., Grand Island, NY, USA), l-glutamine (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and penicillin–streptomycin–amphotericin B (Sigma–Aldrich). Then, the aspirates were seeded onto 100-mm culture dishes and incubated in a humidified 5% CO2–95% air environment at 37 °C. The medium was replaced every 2 days. Approximately 10–14 days after seeding, the adherent cells, which were nearly confluent, were released from the dish by a 5-min exposure to 0.25% trypsin and 0.02% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). The cells were subcultured, and before the cells approached confluence again (Fig. 1), they were harvested using the same methods described above. The mean cell count was 2.14 ± 0.42 × 107 (range: 0.2–2.8 × 107).

Fig. 1.

Phase-contrast micrograph of a culture of live bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells released by harvesting with trypsin–EDTA. Bar: 50 μm.

Concurrently with bone marrow aspiration, peripheral blood was also drawn and the serum was extracted from the whole blood by centrifuging 5 mL of peripheral blood at 3500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was extracted as autologous serum and frozen at −80 °C until use during the cell injection as a suspension medium.

2.2. Surgical protocol and cell injection

The dogs were anaesthetized as described above, and then the knee was exposed using a standard medial parapatellar approach. A full-thickness chondral defect was created in the patella groove of the femur using an 8-mm diameter disposable biopsy punch (Kai Industries Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The base of the defect was smoothed with a small chisel. Next, nine holes were drilled into the defect using a 0.9 mm diameter wire (ConMed Linvatec Biomaterials, Ltd., Tampere, Finland) as bone marrow stimulation (Fig. 2). Then, BMSCs suspended in 500 μL of autologous serum and 500 μL of purified 1% HA (ARTZ Dispo; Kaken Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were directly injected into the defect (drilling and cells in HA: BMSC group). The same defect creation and drilling was performed on the opposite knee joint, but HA and autologous serum alone, i.e., without the BMSC transplantation, was injected as a control (drilling, HA, and serum alone: control group). Finally, the joint capsule and skin were closed with 3-0 nylon sutures. Care was taken to avoid any leakage of the injected solutions into the extra-articular tissue during the procedure. All the dogs were returned to their cages after the operation and allowed to move freely.

Fig. 2.

A full-thickness chondral defect was created in the femoral groove using an 8-mm diameter disposable biopsy punch. The base of the defect was smoothed with a surgical scalpel. Then, nine holes were drilled into the defect using 0.9 mm-diameter wire as bone marrow stimulation.

2.3. Evaluation

Five dogs were euthanized 3 months after the BMSC injection and 10 dogs were euthanized 6 months after surgery using an intravenous overdose of pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal, Dainippon Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Osaka, Japan).

2.4. Macroscopic evaluation

The macroscopic tissue regeneration was evaluated as the percentage of coverage area using ImageJ software [20] and the International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) score [21]. The ICRS scoring system includes three categories: the degree of defect repair, integration at the border zone, and the macroscopic appearance, with a maximum score of 12 (best result). The degree of defect repair was graded from 0 (0% repair of the defect depth) to 4 points (repair level with the surrounding cartilage). The integration at the border zone was graded from 0 (no contact to 25% of the graft was integrated with the surrounding cartilage) to 4 points (complete integration with the surrounding cartilage). The macroscopic appearance was graded from 0 (total degeneration of the grafted area) to 4 points (an intact smooth surface).

2.5. Histology

Each harvested knee was fixed in 4% neutral formalin, decalcified in 0.5 M EDTA, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and embedded in paraffin. The specimens were cut in the oblique sagittal direction to 5-μm thickness with a microtome (Leica Microsystems, Inc., Wetzlar, Germany) and stained with toluidine blue. The Wakitani histological scoring system [9] was used. This scale includes five categories: cell morphology, matrix staining, surface regularity, thickness of cartilage, and integration with the adjacent host cartilage, with a maximum score of 14 (poorest result). The cell morphology was graded from 0 (tissue that appeared normal compared with the adjacent, uninjured cartilage) to 4 points (cartilage tissue was absent). Matrix staining, or the degree of metachromasia, was graded from 0 (tissue that appeared normal compared with the adjacent, uninjured cartilage) to 3 points (no metachromatic staining). Surface regularity, or the proportion of the defect surface that appeared smooth compared with the entire surface, was graded from 0 (more than three quarters of the surface was smooth) to 3 points (less than one quarter of the surface was smooth). The thickness of cartilage, or the average thickness of the cartilage in the defect compared with the surrounding cartilage, was graded from 0 (the average thickness of the repair tissue in the defect was more than two-thirds that of the surrounding cartilage) to 2 points (the average thickness was less than one-third that of the surrounding cartilage). Integration of the repair tissue with the host cartilage was graded from 0 (no gap between the repair tissue and host cartilage) to 2 points (a complete lack of integration).

2.6. Statistical analysis

The total macroscopic and histological scores were compared between the BMSC and control groups, as well as between 3 and 6 months after the operation within each group, using paired t-tests and Mann–Whitney U tests. P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were performed in Excel 2010 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Macroscopic evaluation

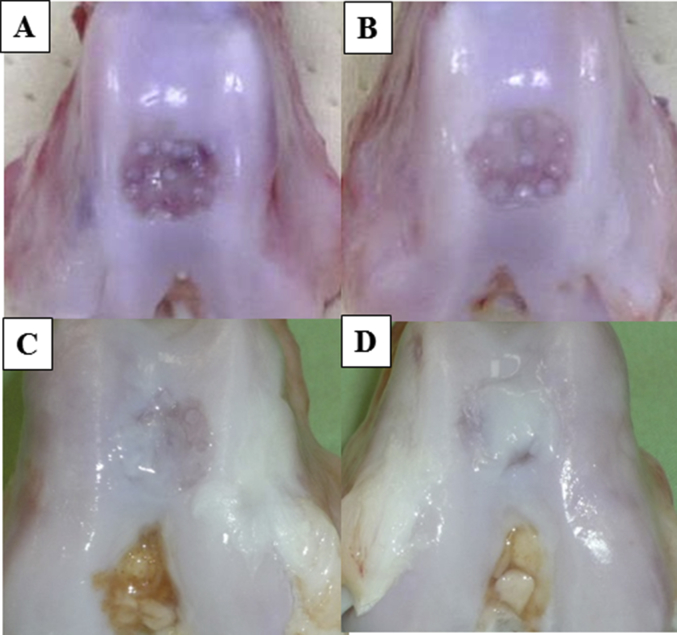

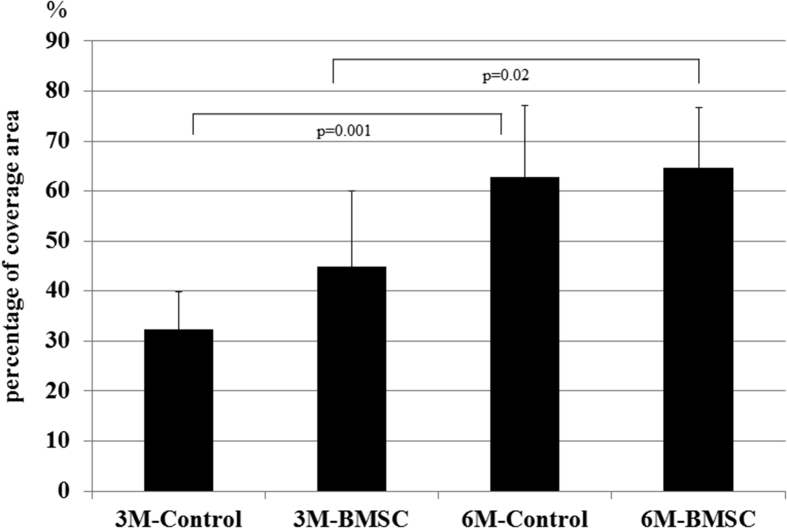

No signs of osteoarthritis, such as osteophytes or cyst formation, were found around the defect area. At 3 months, the defects in the control group had very little covering. In contrast, the defects in the BMSC group were partially covered with repair tissue. However, the mound covering the drill holes remained visible because of the thin repair tissue coverage. At 6 months, the defects in the control and BMSC groups were filled with much more repair tissue than those at 3 months, and the drilling scar was no longer visible (Fig. 3). The mean percentage of coverage area in the control group was 32.4 ± 6.6% at 3 months and 62.8 ± 8.8% at 6 months, and of the BMSC group was 44.8 ± 13.2% at 3 months and 64.7 ± 7.5% at 6 months. Although there were significant differences between the coverage areas at 3 months and 6 months in both the control (p = 0.001) and BMSC (p = 0.02) groups, no significant difference was found between the control and BMSC groups at either 3 or 6 months (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Macroscopic images of the A) 3 M control, B) 3 M BMSC, C) 6 M control, and D) 6 M BMSC groups. There were no signs of osteoarthritis, such as osteophytes or cyst formation, around the defect area. At 3 months, the defects in the control group showed no coverage with repair tissue. The defects in the BMSC group were covered by a little repair tissue. However, the scar from the drilling remained visible. At 6 months, the defects in the control and BMSC groups were filled with much more repair tissue than those at 3 months, and the scar from drilling was no longer visible. Moreover, the defect coverage in the BMSC group appeared better than that in the control group.

Fig. 4.

Mean percentage of coverage area in the control group was 32.4 ± 6.6% at 3 months and 62.8 ± 8.8% at 6 months, and that of the BMSC group was 44.8 ± 13.2% at 3 months and 64.7 ± 7.5% at 6 months. Although there were significant differences between the coverage areas at 3 and 6 months in both the control (p = 0.001) and BMSC (p = 0.02) groups, no significant difference was found between the control and BMSC groups at either 3 or 6 months.

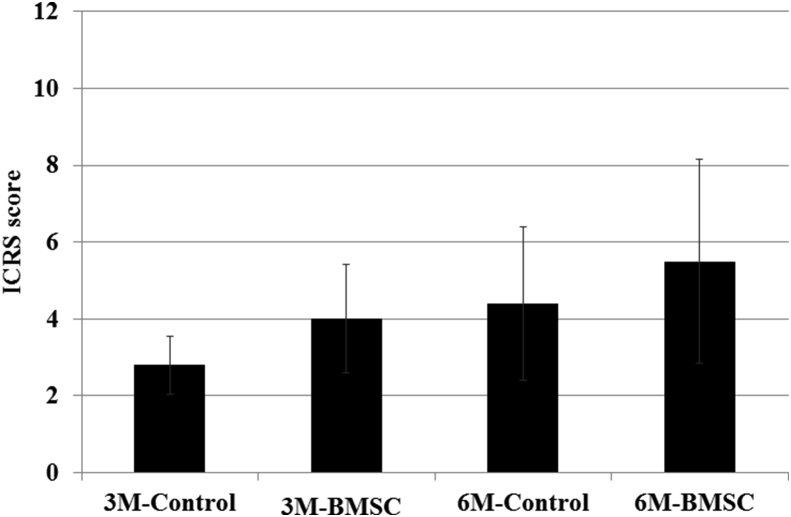

3.1.1. Comparison of ICRS scores at 3 and 6 months

The mean ICRS score of the control group was 2.8 ± 0.7 at 3 months and 4.4 ± 1.3 at 6 months (p = 0.13), and that of the BMSC group was 4.0 ± 1.2 at 3 months and 5.5 ± 1.7 at 6 months (p = 0.29). Although the ICRS scores at 6 months appeared better than those at 3 months, no significant difference was found between the 3 and 6 month data in either group (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Mean ICRS scores of the control and BMSC groups were 2.8 ± 0.7 and 4.0 ± 1.2 at 3 months and 4.4 ± 1.3 and 5.5 ± 1.7 at 6 months. No significant differences were found between the 3 and 6 month data in the control (p = 0.13) or BMSC (p = 0.29) groups or between the control and BMSC groups at 3 (p = 0.07) or 6 (p = 0.10) months.

3.1.2. Comparison of ICRS scores between the BMSC and control groups

The mean ICRS score at 3 months was 2.8 ± 0.7 in the control group and 4.0 ± 1.2 in the BMSC group (p = 0.07), and the ICRS score at 6 months was 4.4 ± 1.3 in the control group and 5.5 ± 1.7 in the BMSC group (p = 0.09). Although the ICRS scores in the BMSC group appeared better than those in the control group, no significant difference was found between the control and BMSC groups (Fig. 5).

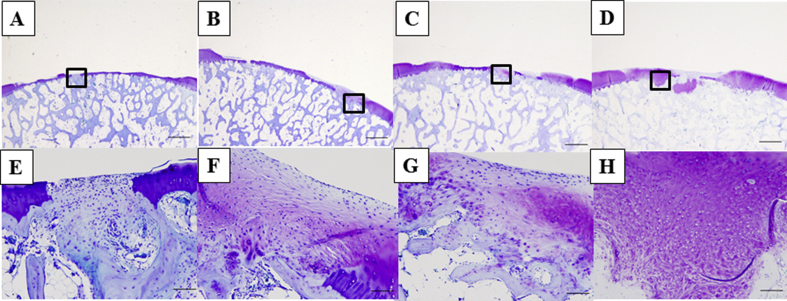

3.2. Histology

At 3 months, although the defects were partially filled with a fibrous tissue at the drilling sites, most of the control specimens contained no cartilage tissue (Fig. 6A and E). In the BMSC group, the defects were partially filled with a hyaline-like cartilage repair tissue originating from the drilling site, and a portion of the regenerated tissue extended and connected to the normal cartilage (Fig. 6B and F). At 6 months, although the amount of repair tissue filling the defects in the control group was markedly better than that at 3 months, the tissue consisted of fibrocartilage showing little metachromasia (Fig. 6C and G). In the BMSC group, the regeneration occurred not only at the drilling site, but also at the site adjacent to the normal cartilage that was not drilled, indicating better repair than that found at 3 months. Moreover, portions of the tissue appeared similar to hyaline-like cartilage and showed qualitative improvements in metachromasia, surface regularity, and repair tissue thickness compared with the control group (Fig. 6D and H).

Fig. 6.

Histology of the repair tissue in the A), D) control group at 3 months (Wakitani score: 10); B), E) BMSC group at 3 months (Wakitani score: 7); C), F) control group at 6 months (Wakitani score: 5); and D), G) BMSC group at 6 months (Wakitani score: 3). Upper row bar: 1.0 mm; lower row shows magnifications of the framed areas in each panel of the upper row, bar: 100 μm. At 3 months, although the defects were partially filled with a fibrous tissue at the drilling sites, most of the control specimens contained no cartilage tissue (A, E). In the BMSC group, the defects were partially filled with a hyaline-like cartilage repair tissue originating from the drilling site, and a portion of the regenerated tissue extended and connected to the normal cartilage (B, F). At 6 months, although markedly more repair tissue was found filling the defects in the control group than that at 3 months, the tissue consisted of fibrocartilage showing little metachromasia (C, G). In the BMSC group, the regeneration at 6 months occurred not only at the drilling site, but also at the sites adjacent to normal cartilage that were not drilled and was better than that found at 3 months. Moreover, portions of the tissue appeared similar to hyaline-like cartilage and showed qualitative improvements in metachromasia, surface regularity, and repair tissue thickness compared with those in the control group (D, H).

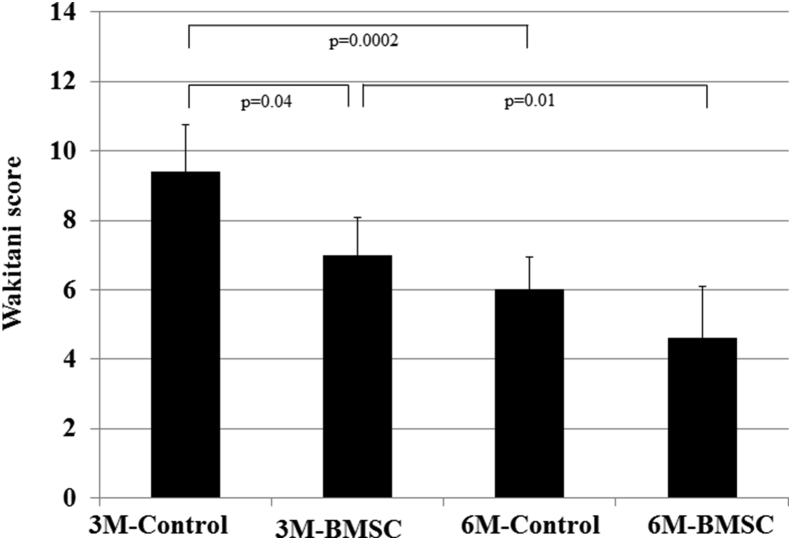

3.2.1. Comparison of Wakitani scores at 3 with 6 months

The mean Wakitani score of the control group was 9.4 ± 1.2 at 3 months and 6.0 ± 0.6 at 6 months (p = 0.0002), and that of the BMSC group was 7.0 ± 1.0 at 3 months and 4.6 ± 0.9 at 6 months (p = 0.01). The histological regeneration at 6 months was significantly better than that at 3 months in both groups (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Mean Wakitani scores of the control group and the BMSC group were 9.4 ± 1.2 and 7.0 ± 1.0 at 3 months and 6.0 ± 0.6 and 4.6 ± 0.9 at 6 months. Both the control and BMSC groups showed significantly better regeneration at 6 months than at 3 months (control: p = 0.0002; BMSC: p = 0.01). The BMSC group showed significantly better regeneration than the control group at 3 months (p = 0.04), but those differences were not significant at 6 months (p = 0.06).

3.2.2. Comparison of Wakitani scores in the BMSC and control groups

The mean Wakitani score at 3 months was 9.4 ± 1.2 in the control group and 7.0 ± 1.0 in the BMSC group (p = 0.04), and the Wakitani score at 6 months was 6.0 ± 0.6 in the control group and 4.6 ± 0.9 in the BMSC group (p = 0.06). Although the BMSC group showed better regeneration than the control group at 3 months, no significant difference was found between the control and BMSC groups at 6 months (Fig. 7).

4. Discussion

The effects of treating chondral defects using the direct injection of BMSCs in HA were assessed in this study. The results suggest that the direct injection of BMSCs suspended in HA combined with bone marrow stimulation as a treatment for chondral defects in the femoral groove significantly improves cartilage regeneration compared with that achieved in the bone marrow stimulation and HA injection alone control group, as assessed by histological examination using the Wakitani score at 3 months. Although there was no significant difference between the control and BMSC groups at 6 months, the p-value (0.06) was nearly significant. Including additional BMSC samples using this same method would likely achieve a significant difference.

We used drilling as a bone marrow stimulation technique together with transplantation of BMSCs in HA to enhance the healing potential of cartilage. Bone marrow stimulation creates channels through the subchondral bone that allow blood and bone marrow elements, including the mesenchymal stem cells that contribute to cartilage healing, access to the damaged surface [4]. The histologic results shown here indicate that chondral repair mainly occurred in the drilled sites at 3 months, but repair was found even in the non-drilled sites at 6 months. Agung et al. reported that injected green fluorescent protein-labeled BMSCs had an affinity for damaged joint tissues, localizing and participating in the repair of damaged cartilage lesions [16]. In addition, Caplan and Dennis [22] reported that BMSCs have the potential not only to differentiate into several mesenchymal phenotypes, such as osteoblasts, chondrocytes, myocytes, marrow stromal cells, tendon-ligament fibroblasts, and adipocytes, but also to secrete a variety of cytokines and growth factors. These factors have both paracrine and autocrine effects, including the suppression of the local immune system and apoptosis and the inhibition of fibrosis, as well as the stimulation of mitosis and the differentiation of stem cells [22]. Based on the present results and those from previous reports, BMSCs appear to contribute directly to cartilage repair by differentiating into target cells that synthesize new tissue and contribute indirectly by enhancing the effects of the endogenous BMSCs.

Several previous reports have shown the efficacy of intra-articular BMSC injection for chondral defect repair. McIlwraith et al. demonstrated the benefits of the intra-articular injection of BMSCs combined with microfracture compared with microfracture alone for treating full-thickness defects in equine medial femoral condyles. The arthroscopic and gross evaluations showed a trend for better overall repair tissue quality in the BMSC-treated joints, and the immunohistochemical analysis also showed significantly higher levels of aggrecan in the BMSC injection group after 12 months [18]. Nam et al. reported that the intra-articular injection of BMSCs combined with drilling enhanced the healing of full-thickness chondral defects significantly more than the drilling alone control in a caprine model, as assessed by macroscopic ICRS scoring, histological O'Driscoll scoring, and immunohistochemical analyses including glycosaminoglycan content and chondrogenic gene expression of aggrecan, collagen II, and Sox9 [19]. In the present study, we used beagle dogs and created an 8.0 mm diameter chondral defect and drilled nine 0.9-mm diameter holes in the femoral groove, not in the medial condyle, before injecting approximately 2.14 × 107 BMSCs suspended in HA.

This unique protocol was used in the present study because the injection of BMSCs, HA, and autologous serum, as well as the drilling technique, were all performed for the chondral defect. Nam et al. performed drilling and BMSC transplantation without HA, while McIlwraith et al. performed drilling and BMSC transplantation with HA, but without serum. HA may improve cartilage healing by coating the cartilage surface and localizing in the cartilage extracellular matrix among the collagen fibrils and proteoglycans [23], increasing synovial cell migration [24]. These effects may explain why the histological score of the control group was improved at 6 months compared with that at 3 months after surgery in the present study. However, the repair tissue created in the control group was mainly fibrocartilaginous, similar to the results of previous reports [25], [26], [27]. Therefore, BMSCs are likely essential for achieving cartilage repair. Regarding the effects of autologous serum, IL-1 is the most potent known mediator of cartilage loss. Autologous serum is an effective treatment for osteoarthritis because it contains IL-1 receptor antagonist. Therefore, even the control group in the present study had a certain potential for chondral repair [28]. Moreover, the repair was evaluated in the present study using quantitative measures for the macroscopic and histologic findings that were different than those used by McIlwraith et al.

One limitation of the present study is that the regeneration of the chondral defects using the BMSC did not achieve a completely normal articular cartilage. We did not induce chondrogenic differentiation of the BMSCs before injection in this experiment. According to Marquass et al., chondrogenically predifferentiated BMSCs lead to better chondral regeneration than undifferentiated BMSCs [29]. In addition, several studies have reported that exogenous basic fibroblast growth factor-2 accelerates cartilage repair [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]. Another limitation is that we used a canine model in this study, which may demonstrate different cartilage regeneration properties than those that occur in humans. In humans, a few relevant clinical case reports [35], [36], [37] and one prospective, randomized controlled clinical study [38] have been reported. Wong et al. demonstrated that the intra-articular injection of cultured BMSCs improves both the short-term clinical and MRI outcomes in patients undergoing HTO and microfracture for varus knees with cartilage defects. However, these clinical reports included patients with knee osteoarthritis, not focal chondral defects. Further work establishing clinical trials for the intra-articular injection of BMSCs to treat human chondral defects is needed.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the direct injection of BMSCs suspended in HA combined with bone marrow stimulation for treating chondral defects in the femoral groove appeared to improve cartilage regeneration compared with bone marrow stimulation and HA injection alone controls based on macroscopic and histologic findings. The histological results showed that BMSC injection significantly enhanced chondral regeneration beyond what was found in the control group at 3 months.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of the Japanese Society for Regenerative Medicine.

Contributor Information

Shinya Yamasaki, Email: fcbackspin@hotmail.com.

Yusuke Hashimoto, Email: hussy@med.osaka-cu.ac.jp.

Junsei Takigami, Email: m1294921@msic.med.osaka-cu.ac.jp.

Shozaburo Terai, Email: ilizarov923@gmail.com.

Hisashi Mera, Email: hisme0214@gmail.com.

Hiroaki Nakamura, Email: hnakamura@med.osaka-cu.ac.jp.

Shigeyuki Wakitani, Email: swakitani44@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Hunziker E.B. Articular cartilage repair: basic science and clinical progress. A review of the current status and prospects. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2002;10:432–463. doi: 10.1053/joca.2002.0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Messner K., Gillquist J. Cartilage repair. A critical review. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:523–529. doi: 10.3109/17453679608996682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shelbourne K.D., Jari S., Gray T. Outcome of untreated traumatic articular cartilage defects of the knee: a natural history study. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2003;85:8–16. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200300002-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steadman J.R., Briggs K.K., Rodrigo J.J., Kocher M.S., Gill T.J., Rodkey W.G. Outcomes of microfracture for traumatic chondral defects of the knee: average 11-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:477–484. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brittberg M., Lindahl A., Nilsson A., Ohlsson C., Isaksson O., Peterson L. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:889–895. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsusue Y., Yamamuro T., Hama H. Arthroscopic multiple osteochondral transplantation to the chondral defect in the knee associated with anterior cruciate ligament disruption. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:318–321. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(05)80428-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hangody L., Rathonyi G.K., Duska Z., Vasarhelyi G., Fules P., Modis L. Autologous osteochondral mosaicplasty. Surgical technique. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2004;86:65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basad E., Ishaque B., Bachmann G., Sturz H., Steinmeyer J. Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation versus microfracture in the treatment of cartilage defects of the knee: a 2-year randomised study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18:519–527. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-1028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wakitani S., Goto T., Pineda S.J., Young R.G., Mansour J.M., Caplan A.I. Mesenchymal cell-based repair of large, full-thickness defects of articular cartilage. J Bone Jt Surg. 1994;76:579–592. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199404000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wakitani S., Mitsuoka T., Nakamura N., Torituska Y., Nakamura N., Horibe S. Autologous bone marrow stromal cell transplantation for repair of full-thickness articular cartilage defects in human patellae: two case reports. Cell Transplant. 2004;13:595–600. doi: 10.3727/000000004783983747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wakitani S., Nawata M., Tensho K., Okabe T., Machida H., Ohgushi H. Repair of articular cartilage defects in the patellofemoral joint with autologous bone marrow mesenchymal cell transplantation: three case reports involving nine defects in five knees. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2007;1:74–79. doi: 10.1002/term.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuroda R., Ishida K., Matsumoto T., Akisue T., Fujioka H., Mizuno K. Treatment of a full-thickness articular cartilage defect in the femoral condyle of an athlete with autologous bone-marrow stromal cells. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007;15:226–231. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakitani S., Imoto K., Yamamoto T., Saito M., Murata N., Yoneda M. Human autologous culture expanded bone marrow mesenchymal cell transplantation for repair of cartilage defects in osteoarthritic knees. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2002;10:99–206. doi: 10.1053/joca.2001.0504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamasaki S., Mera H., Itokazu M., Hashimoto Y., Wakitani S. Cartilage repair with autologous bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation: review of preclinical and clinical studies. Cartilage. 2014;5:196–202. doi: 10.1177/1947603514534681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wakitani S., Okabe T., Horibe S., Mitsuoka T., Saito M., Koyama T. Safety of autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for cartilage repair in41 patients with 45 joints followed for up to 11 years and 5 months. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2011;5:146–150. doi: 10.1002/term.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agung M., Ochi M., Yanada S., Adachi N., Izuta Y., Yamasaki T. Mobilization of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells into the injured tissues after intraarticular injection and their contribution to tissue regeneration. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14:1307–1314. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee K.B., Hui J.H., Song I.C., Ardany L., Lee E.H. Injectable mesenchymal stem cell therapy for large cartilage defects—a porcine model. Stem Cell. 2007;25:2964–2971. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McIlwraith C.W., Frisbie D.D., Rodkey W.G., Kisiday J.D., Werpy N.M., Kawcak C.E. Evaluation of intraarticular mesenchymal stem cells to augment healing of microfractured chondral defects. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:1552–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nam H.Y., Karunanithi P., Loo W.C., Naveen S., Chen H., Hussin P. The effects of staged intra-articular injection of cultured autologous mesenchymal stromal cells on the repair of damaged cartilage: a pilot study in caprine model. Arthritis Res Ther. 2013;15:129–141. doi: 10.1186/ar4309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rasband W.S. U. S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland, USA: 1997-2014. ImageJ.http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Borne M.P., Raijmakers N.J., Vanlauwe J., Victor J., de Jong S.N., Bellemans J. International Cartilage Repair Society (ICRS) and Oswestry macroscopic cartilage evaluation scores validated for use in Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI) and microfracture. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2007;12:1397–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Caplan A.I., Dennis J.E. Mesenchymal stem cells as trophic mediators. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:1076–1084. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maniwa S., Ochi M., Motomura T., Nishikori T., Chen J., Naora H. Effects of hyaluronic acid and basic fibroblast growth factor on motility of chondrocytes and synovial cells in culture. Acta Orthop Scand. 2001;72:299–303. doi: 10.1080/00016470152846664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoshioka M., Shimizu C., Harwood F.L., Coutts R.D., Amiel D. The effects of hyaluronan during the development of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 1997;5:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(97)80021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitchell N., Shepard N. The resurfacing of adult-rabbit articular cartilage by multiple perforations through the subchondral bone. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1976;58:230–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hice G., Freedman D., Lemont H., Khoury S. Scanning and light microscopic study of irrigated and nonirrigated joints following burr surgery performed through a small incision. J Foot Surg. 1990;29:337–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breinan H.A., Martin S.D., Hsu H.P., Spector M. Healing of canine articular cartilage defects treated with microfracture, a type-II collagen matrix, or cultured autologous chondrocytes. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:781–789. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baltzer A.W., Moser C., Jansen S.A., Krauspe R. Autologous conditioned serum (Orthokine) is an effective treatment for knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2009;17:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marquass B., Schulz R., Hepp P., Zscharnack M., Aigner T., Scmidt S. A. Matrix-associated implantation of predifferentiated mesenchymal stem cells versus articular chondrocytes: in vivo results of cartilage repair after 1 year. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39:1401–1412. doi: 10.1177/0363546511398646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holland T.A., Mikos A.G. Advances in drug delivery for articular cartilage. J Control Release. 2003;86:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(02)00373-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chuma H., Mizuta H., Kudo S., Takagi K., Hiraki Y. One day exposure to FGF-2 was sufficient for the regenerative repair of full-thickness defects of articular cartilage in rabbits. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2004;12:834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deng T., Huang S., Zhou S., He L., Jin Y. Cartilage regeneration using a novel gelatin-chondroitin-hyaluronan hybrid scaffold containing bFGF-impregnated microspheres. J Microencapsul. 2007;24:163–174. doi: 10.1080/02652040701233523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukuda A., Kato K., Hasegawa M., Hirata H., Sudo A., Okazaki K. Enhanced repair of large osteochondral defects using a combination of artificial cartilage and basic fibroblast growth factor. Biomaterials. 2005;26:4301–4308. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maehara H., Sotome S., Yoshii T., Torigoe I., Kawasaki Y., Sugata Y. Repair of large osteochondral defects in rabbits using porous hydroxyapatite/collagen (HAp/Col) and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) J Orthop Res. 2010;28:677–686. doi: 10.1002/jor.21032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centeno C.J., Busse D., Kisiday J., Keohan C., Freeman M., Karli D. Increased knee cartilage volume in degenerative joint disease using percutaneously implanted, autologous mesenchymal stem cells. Pain Physician. 2008;11:343–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davatchi F., Abdollahi B.S., Mohyeddin M., Shahram F., Nikbin B. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy for knee osteoarthritis. Preliminary report of four patients. Int J Rheum Dis. 2011;14:211–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1756-185X.2011.01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emadedin M., Aghdami N., Taghiyar L., Fazeli R., Moghadasali R., Jahamgir S. Intraarticular injection of autologous mesenchymal stem cells in six patients with knee osteoarthritis. Arch Iran Med. 2012;15:422–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wong K.L., Lee K.B., Tai B.C., Law P., Lee E.H., Hui J.H. Injectable cultured bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in varus knees with cartilage defects undergoing high tibial osteotomy: a prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial with 2 years' follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:2020–2028. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2013.09.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]