ABSTRACT

Background

US Dietary Guidelines include recommendations to increase whole-grain consumption, but most Americans, especially low-income adults, fail to consume adequate amounts.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to determine major factors that may affect whole-grain consumption among low-income adults.

Methods

A mixed methods approach including a whole-grain food identification activity and in-depth interview was used to determine the factors that influence whole-grain consumption based on the constructs of the integrative behavioral model. Participants were recruited from food pantries in the northeastern United States. Descriptive statistics were conducted for demographic data and survey scores, and logistic regression was used to examine differences in whole-grain accuracy by demographic characteristics.

Results

Low-income adults (n = 169) completed a quantitative survey, with a subset (n = 60) recruited for an in-depth qualitative interview. When completing the whole-grain identification activity, most low-income adults identified popcorn incorrectly as refined grain (71%), whereas the refined-grain food commonly identified as whole grain was white rice (42%). Less than half of low-income adults (46%) identified the majority of whole-grain foods correctly. Age, race, and education were not associated with the ability to identify whole-grain foods correctly. However, younger adults (aged 18–49 y) were less likely to identify popcorn as a whole-grain food (OR = 0.42, P = 0.02) compared with older adults (aged ≥50 y). According to the qualitative results, additional barriers, such as perceived cost, may also affect whole-grain food consumption among low-income adults.

Conclusions

Low-income adults’ ability to correctly identify whole-grain foods and having a perception that whole-grain foods are higher in cost may be the overarching barriers to consuming adequate amounts. Future efforts should focus on strategies improving identification and seeking affordable whole-grain foods to increase whole-grain consumption in low-income adults.

Keywords: dietary guidelines, health behavior, food packaging, ingredient information, popcorn, mixed methods

Introduction

Whole-grain foods contribute good sources of nutrients to the diet, such as fiber, B vitamins, iron, magnesium, and zinc, that are beneficial for health (1). Higher consumption of whole-grain foods by children, adolescents, and adults is associated with improved consumption of nutrients, dietary components, and overall diet quality (2–4). Individuals who consume whole-grain foods may have healthier body weight and decreased risk for developing cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and certain cancers (5–7).

The 2015–2020 US Dietary Guidelines for Americans states that “a healthy eating pattern includes . . . grains, at least half of which are whole grains” (e.g., 3 oz equivalents of whole grains out

of 6 oz of total grains) (2). Although consumer interest in whole-grain foods has increased (8, 9), consumption recommendations are not being met by most Americans. Only 2.9% of children and adolescents and 7.7% of adults consume the recommended amount of whole grains each day in the United States (10). In low-income populations, whole-grain consumption is <1 oz per day (11). Similarly, whole-grain consumption is also below recommended amounts in both the general and low-income populations in the United Kingdom (12), with recommendations for whole grains stated as “choose wholegrain or fibre versions with less added fat, salt, and sugar” (13).

The term “whole grain” has been previously defined, but “whole-grain food” currently lacks a standardized definition, potentially contributing to confusion and inconsistency in labeling and the identification of food products containing whole grain (14, 15). Thus, 1 potential strategy for increasing whole-grain foods in the diet may be related to the information of whole-grain content present on food packaging. Prior studies have demonstrated that identification of whole grains is difficult among food service professionals (16, 17) and also health club members (18).

Nutrition education interventions seeking to improve whole-grain consumption have primarily focused on behavior changes. Two studies reported increases in whole-grain consumption among youth with type 1 diabetes (19) and healthy adolescents and their families (20). However, 1 intervention conducted with middle school students did not report any increases in whole-grain consumption (21). A limitation across these studies was that the factors influencing the decision to consume whole grains were not assessed prior to the intervention. Factors influencing consumption and poor whole-grain intake among Americans warrant examination of behaviors affecting the selection and consumption of whole-grain foods by individuals (22). For instance, personal attitudes may influence food choices and serve as a contributing factor to consuming a healthier diet (23). A previous study assessed attitudes of young adults aged 18–29 y regarding whole-grain food consumption (24), but factors such as identification, cost, taste, texture, self-efficacy, and interpersonal influences were not examined. Furthermore, these factors were not evaluated in low-income adults.

The integrative behavioral model (IBM) is composed of constructs from both the theory of reasoned action and the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (25). IBM predicts an individual's intended decision to perform a behavior based on 3 constructs: attitudes, perceived norms, and personal agency (26). The attitude construct is composed of experiential attitude and instrumental attitude. Experiential attitude is an individual's emotional response to performing a recommended behavior (27), whereas an individual eliciting a positive emotional response is more likely to engage in the recommended behavior (28). Instrumental attitude is determined by the beliefs regarding the outcomes of a recommended behavior (28). Perceived norms include injunctive norms and descriptive norms. Injunctive norms are beliefs expressed by the individual with regard to performing the recommended behavior based on the perceived approval or disapproval of others (29). Descriptive norms are beliefs about the proportion of people in the population who are performing the behavior (28). The third construct, personal agency, involves perceived behavioral control, which is defined as perceived control over the recommended behavior as determined by environmental factors that make it easier or difficult to perform the behavior (28). An additional component is self-efficacy, which is confidence in the ability to perform the behavior despite constraints or challenges (28). Formative research studies have examined the relation between the constructs of the TPB and behavioral intention with regard to predicting dairy consumption in older adults (30), increasing vegetable consumption in high school students (31), and examining sugar-sweetened beverage and water consumption in adults (32). Usage of IBM is emerging in nutrition intervention studies, with 1 study using the framework to evaluate monitoring of fruits and vegetables and also sugar-sweetened beverages with low-income mothers (33). Factors related to whole-grain consumption include preferences for whole-grain foods based on promoting health and sensory characteristics, family influence, identifying whole-grain products, whole-grain preparation skills, and the cost of whole-grain foods, which are applicable to the constructs of IBM. To further determine the factors that influence whole-grain consumption, along with referents, facilitators, and barriers for each behavior in the target population, an important step is conducting open-ended interviews based on the IBM constructs (34). Therefore, the aims of this research were to 1) assess the accuracy of low-income adults’ ability to identify commonly consumed whole-grain foods and determine if accuracy differs by demographic characteristics, 2) determine the process by which low-income adults identify grain foods as whole grains, and 3) determine which factors are predominant in influencing whole-grain consumption among low-income adults based on the constructs of IBM.

Methods

The study included both qualitative and quantitative surveys. Both components of the study were deemed exempt by the University of Connecticut–Storrs Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects. An information sheet was provided to each participant, and verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants and witnessed by the researchers.

Quantitative survey

Low-income adults were recruited to participate in the “Whole Grains Detective Challenge” activity held at mobile food pantry sites, which distribute food from food banks and donations to low-income adults and their families (35). This activity also occurred at a health fair targeting low-income families. The eligibility criteria for the study were adults aged ≥18 y who could speak and read English and eligibility or participation in a US federally funded program, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Education (SNAP-Ed), the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program, or enrollment in a government-funded insurance plan. Program eligibility or site participation served as a proxy for income. A minimum sample size of n = 108 was deemed sufficient to achieve power of 80% with a medium effect size (0.3).

The whole-grain activity quantitative questionnaire involved the process of a participant viewing 11 grain foods in their original packaging on a nutrition display and determining if the food was a whole grain or not. For this display, commonly consumed foods as part of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) recommendations were chosen based on having either 100% whole-grain ingredients or 0% whole-grain ingredients. The display included 5 whole-grain and 6 refined-grain foods (whole-grain bread, whole-grain cereal, popcorn, oatmeal, whole-grain crackers, refined-grain cereal, refined-wheat bread, refined white flour tortilla, white rice, refined-grain crackers, and refined elbow macaroni). Prior to use, the questionnaire was reviewed for content validity by the study team. On the questionnaire, low-income adults indicated which foods were whole grains. They also completed a 7-item demographic form and self-reported characteristics such as race. For the purposes of brevity, race categories such as “African American or black” are abbreviated as “black” in this study. A small thank-you incentive such as a whole-grain snack was provided for their time.

Qualitative survey

To better understand how and why low-income adults identify and consume whole grains, an additional qualitative interview was randomly conducted with a subsample of the participants completing the quantitative survey. The eligibility requirements were the same as those for the Whole Grains Detective Challenge. Once an adult indicated interest in the study and met the eligibility criteria, he or she completed the Whole Grains Detective Challenge survey and then immediately participated in a 10-min qualitative interview (if willing) that contained 5 questions (Table 1) to assess reported barriers to whole-grain consumption. Prior to use, the script was reviewed for content validity by the research team, and it was based on the IBM constructs (28). These factors included health reasons and sensory properties of whole grains (attitudes toward the behavior), influence of family members and peers (perceived norms), identification (perceived control), and perceived cost of whole grains and skills (self-efficacy) (18, 36–39). The 10-min interview included in-depth questions regarding the identification of whole-grain foods from the Whole Grain Detective Challenge. The interview involved reviewing a second set of 11 grain food packages from the quantitative survey to address how the participant determined if the food was whole or refined grain. Responses from the low-income adults were recorded in detail on the questionnaire by the researcher. For completing the 10-min interview, each participant received a grocery bag filled with whole-grain cereal, pasta, recipes, and resources worth $8.

TABLE 1.

Whole Grains Detective Challenge qualitative interview questions

| Question content | Question |

|---|---|

| Identification of whole-grain or refined-grain food | How did you go about identifying the food as whole grain or not? |

| Integrative behavioral model constructs | |

| Attitudes: health | What are your plans to eat whole grains for any health reasons? |

| Attitudes: sensory | How does the look and taste of whole grain foods affect how you eat? |

| Subjective norm: family influence | How does your family affect what whole grain foods you buy and eat? |

| Perceived behavioral control: cost | How does the cost of whole grain foods affect if you buy them? |

| Self-efficacy: identification | When grocery shopping, can you describe how easy it is to decide if a food is whole grain? |

| Self-efficacy: skills | How does your ability to prepare whole grain foods affect how often you eat them? |

Quantitative analysis

Descriptive analysis of demographics and accuracy of whole-grain identification was conducted using IBM SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp.). For each food item, participants were assigned a score of 1 if the food item was correctly identified as whole grain or refined grain. If the food item was incorrectly identified, a score of 0 was assigned. The data were then coded to categorize adults as “1” if they identified ≥4 whole grains correctly (total whole-grain score = ≥4) or “0” if they identified ≤3 whole-grain foods correctly (total whole-grain score = ≤3). Logistic regression was used to determine if demographic characteristics (as categorical independent variables) were associated with ability/total whole-grain score (dependent variable) to identify all whole-grain foods correctly. ORs were considered statistically significant if P ≤ 0.05.

Qualitative analysis

The replies to the 10-min interviews were coded to analyze responses from the low-income adults using the classical analysis approach (40). Prior to initial coding, each food item was categorized based on how the adult identified the food from the quantitative survey—“identified as whole grain” or “identified as refined grain”—and then coded accordingly based on the adult's observations, opinions, or behaviors associated with the food. The codes for each food item were used to determine the major and emerging themes regarding identification. For the responses based on the IBM constructs, each adult's response was coded, and codes representing similar behaviors and perceptions were categorized to determine major and emerging themes.

Results

Quantitative results

The mean age of low-income adults (n = 169) participating in the quantitative survey was 49.1 ± 15.6 y (range: 18–80 y; Table 2). The majority of adults were women (73%), white (75%), and had completed less than a bachelor's degree (85%) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Demographic information of low-income adults participating in the Whole Grains Detective Challenge (n = 169) and qualitative interview (n = 60)1

| Characteristic | Quantitative survey (n = 169) | Qualitative interview (n = 60) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender2 | ||

| Male | 45 (27) | 17 (28) |

| Female | 123 (73) | 43 (72) |

| Race3 | ||

| White | 126 (75) | 46 (77) |

| Black | 22 (13) | 7 (12) |

| Other | 15 (9) | 4 (7) |

| Ethnicity4 | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 140 (83) | 51 (85) |

| Hispanic | 24 (14) | 7 (12) |

| Education level | ||

| < High school | 16 (10) | 10 (17) |

| High school diploma or GED | 54 (32) | 21 (35) |

| Technical or vocational school | 21 (12) | 5 (8) |

| Some college | 39 (23) | 13 (22) |

| Associate's degree | 14 (8) | 5 (8) |

| Bachelor's degree | 19 (11) | 4 (6) |

| Graduate or professional degree | 6 (4) | 2 (3) |

| Age,5 y (mean ± SD) | 49.1 ± 16.6 | 47.1 ± 15.6 |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

One adult participating in the quantitative survey did not report gender.

Six adults participating in the quantitative survey and 3 adults participating in the qualitative interview did not report race.

Five adults participating in the quantitative survey and 2 adults participating in the qualitative interview did not report ethnicity.

Two adults participating in the quantitative survey and 1 adult participating in the qualitative interview did not report age.

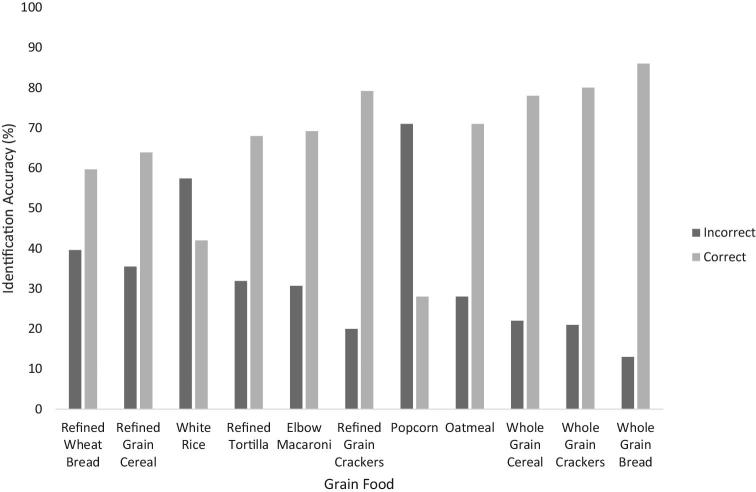

Only 15% of low-income adults identified all 5 whole-grain foods correctly, and less than half of the sample (46%) identified ≤3 whole-grain foods correctly. The whole-grain food that was incorrectly identified as a refined grain most often by low-income adults was popcorn, and white rice was incorrectly identified as whole grain most often (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of low-income adults (n = 169) accurately identifying whole-grain foods.

Age, race, and education were not associated with the overall ability to identify whole-grain foods correctly (Table 3) based on at least 4 or 5 correct responses as the dependent variable. Education level was not associated with the ability to identify whole-grain foods correctly, but it approached significance (P = 0.08). However, for the identification of a single food such as popcorn, younger adults (aged 18–49 y) were less likely to identify popcorn as a whole-grain food (OR = 0.42, P = 0.02) compared with older adults (aged ≥50 y).

TABLE 3.

OR of low-income adults identifying 4 or more whole-grain foods correctly by race, ethnicity, or education level (n = 169)

| Demographic characteristic1 | OR | SE | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| 18–49 (n = 82) | 0.92 | 0.32 | 0.08 |

| ≥50 (n = 85) | Referent | ||

| Race | |||

| White (n = 126) | 0.66 | 0.78 | 0.59 |

| Black (n = 22) | 0.64 | 0.88 | 0.60 |

| Other (n = 15) | Referent | ||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic (n = 140) | 1.41 | 0.71 | 0.62 |

| Hispanic (n = 24) | Referent | ||

| Education level | |||

| Vocational school or less (n = 70) | 0.57 | 0.32 | 0.08 |

| Some college or more (n = 92) | Referent | ||

Not all participants completed the demographic questionnaire; the total sample may be <169.

Qualitative results

To achieve saturation of the qualitative analysis, a total of 60 low-income adults were recruited as a subset from the quantitative survey sample on the same day as they completed the Whole Grains Detective Challenge survey. The mean age of low-income adults (n = 60) participating in the 10-min qualitative interview was 47.1 ± 15.6 y (range: 18–77 y; Table 2). The majority of the adults were women (72%), white (77%), non-Hispanic (85%), and had a high school degree or less (52%) (Table 2).

The majority of adults participating in the interview correctly identified whole-grain bread (87%), whole-grain crackers (85%), and whole-grain cereal (62%) as a whole-grain food (Figure 1) attributed to reading the word “whole grain” on the packaging or viewing the ingredient list (Table 4). The following quote reflects the identification of whole-wheat bread:

“Got it right there whole wheat” (points at whole-wheat bread package). (V12 white man)

However, some adults identified the whole-grain bread based on other characteristics, such as appearance, color, and that “wheat” ingredients are whole grain:

“The way it looks, it looks like it has whole grain. Looked for color.” (V07 white woman)

“Color, darker color is wheat.” (C05 white man)

“Because it's wheat, it would be whole grain.” (V01 white woman)

TABLE 4.

Themes related to identification of grain foods by low-income adults (n = 60)

| Theme and subtheme | Sample quote | |

|---|---|---|

| Whole-grain bread | ||

| Correctly identified the whole-grain food | Theme: viewing the words “whole grain” on the food packaging | “Says whole grain out in the open but read ingredients.” (P24 white woman) |

| Emerging theme: identification of the food based on appearance, color, and assuming that “wheat” is whole grain | “Harder to figure (out), it looks like whole grains by looking at it.” (E04 Hispanic woman) | |

| Incorrectly identified the whole-grain food as refined grain | Theme: item identified incorrectly by overlooking the whole-grain content and focusing on other product characteristics | “Don't like the taste.” (EH06 Hispanic woman) |

| “Didn't notice 100% whole grain.” (P19 white woman) | ||

| Whole-grain cereal | ||

| Correctly identified the whole-grain food | Theme: viewing the words “whole grain” on the food packaging | “Saw it on here. Says whole grain. Not purchased because it has a lot of sugar.” (C04 white man) |

| Incorrectly identified the whole-grain food as refined grain | Theme: focusing on product characteristics and ingredients | “Lot of sugar, no good. Not whole grain.” (E02 white woman) |

| “Looked. Don't look like whole grain.” (V10 black man) | ||

| Popcorn | ||

| Correctly identified the whole-grain food | Theme: lacked understanding to fully identify popcorn as whole grain | “It's corn, therefore whole grain.” (C12 white woman) |

| “Don't think popcorn is a whole grain.” (C07 white woman) | ||

| Incorrectly identified the whole-grain food as refined grain | Theme: popcorn not a whole-grain food | “It's popcorn from corn. Automatic not whole grain.” (EH08 white woman) |

| Subtheme: general assumption that popcorn is not a whole grain | ||

| Oatmeal | ||

| Correctly identified the whole-grain food | Theme: focusing on the product characteristics | “It says heart healthy. Doesn't say 100% whole grain in anything big enough for me to read.” (EH02 black woman) |

| Incorrectly identified the food as refined grain | Theme: focusing on the product characteristics or assumed the product was not whole grain | “Doesn't look it.” (V07 white woman) |

| “Didn't find any sign on it. Wasn't sure.” (EH07 Hispanic woman) | ||

| “Didn't think it was whole grain.” (C08 white man) | ||

| Whole-grain crackers | ||

| Correctly identified the whole-grain food | Theme: reading information on the food packaging to identify the food as whole grain | “Says whole grain on the front and on the ingredient list.” (P24 white woman) |

| Incorrectly identified the whole-grain food as refined grain | Theme: focusing on the product characteristics when identifying the food item | “It doesn't look like whole grain.” (V10 black man) |

| Refined-grain bread | ||

| Correctly identified the whole-grain food | Theme: viewing specific information on the food packaging | “Didn't say it [whole grain].” (C03 white man) |

| Subtheme: looking for whole-grain wording on the food package | “I looked at the label, first the ingredient said enriched . . . that's not whole grain?” (V03 white woman) | |

| Incorrectly identified the refined-grain food as whole grain | Theme: perceived assumptions about the food item characteristics to classify the food item as whole grain | “By the color, the way it looks.” (E07 Hispanic woman) |

| Subtheme: looking at the food label or ingredient list | “Because it's wheat, it would be whole grain.” (V01 white woman) | |

| Subtheme: appearance and color of refined-grain food | ||

| Subtheme: ingredient content of the refined-grain food | ||

| Refined-grain cereal | ||

| Correctly identified the refined-grain food | Theme: perceived assumptions about the food item characteristics to classify the food item as refined grain | “I checked wrong, mini-wheat is, Special K, is junky cereal. I don't care for it.” (C10 white woman) |

| Incorrectly identified the refined-grain food as whole grain | Theme: assuming the product is not whole grain | “Whole grain because of protein.” (V02 other woman) |

| “Had before. Not wheat by color.” (C05 white man) | ||

| White rice | ||

| Correctly identified the refined-grain food | Theme: reading product information | “Read ingredients, brown is better.” (EH01 black woman) |

| Incorrectly identified food as whole grain | Theme: product characteristics and grain wording | “Heavy, said it was grain on box. Not the brand that I usually get.” (C04 white man) |

| Tortilla | ||

| Correctly identified the refined-grain food | Theme: identifying the food based on nutrient or ingredient content | “Not, I read label from the shade of brown assume white flour, usually low fiber.” (V03 white woman) |

| Incorrectly identified the refined-grain food as whole grain | Emerging theme: reading packaging information | “Tortilla is whole grain because of the materials and products used to make it.” (C07 white woman) |

| Refined-grain crackers | ||

| Correctly identified the refined-grain food | Theme: identifying the food based on product characteristics | “I don't think it is because it is light and airy and junky.” (C010 white woman) |

| Emerging theme: reading packaging information | “No by package didn't see anything.” (E04 white woman) | |

| Incorrectly identified the refined-grain food as whole grain | Theme: identifying the food as whole grain based on product characteristics | “Because of the way crackers were made, with grain.” (V02 other woman) |

| Elbow macaroni | ||

| Correctly identified the refined-grain food | Theme: identifying the food based on ingredient content or appearance | “Concentration on fiber.” (E01 white woman) |

| “No, usually white, not food from doctor.” (C04 white man) | ||

| Incorrectly identified the refined-grain as whole grain | Theme: identifying the food based on ingredient content or appearance | “It looks it from the box, the noodles look it.” (V07 white woman) |

| “Considered whole grain because fiber.” (C07 white woman) | ||

Most low-income adults who participated in the qualitative survey incorrectly identified popcorn as a refined-grain food (72%; Figure 1). This was attributed to assuming that popcorn is not whole grain (Table 4), reflected in the following quotes:

“Never heard of any popcorn being whole wheat.” (V01 white woman)

“I've never seen whole-grain popcorn.” (V07 white woman)

Moreover, low-income adults also assumed that the ingredients are not whole grain:

“Didn't think corn was part of grain.” (C07 white man)

“Because it is a bad food because of all the butter and salt.” (P07 white woman)

Although most adults identified oatmeal (Figure 1) as a whole-grain food (77%), the identification was based on the product characteristics, such as the “heart-healthy” information present and ingredient content (Table 4):

“Oats is supposed to be good for you. Heart healthy.” (E01 white woman)

“Whole grain to me because of grain, vitamins.” (P04 white woman)

For identification of refined grain foods (Figure 1), low-income adults identified refined-grain bread (70%) correctly by reviewing specific information on the packaging for the words “whole grain” or on the ingredient list (Table 4):

“Looked at the package to see if it had whole grain and it didn't.” (V11 white woman)

“I read ingredients, looking for whole-wheat flour and no other flours.” (C14 white woman)

Although foods such as refined-grain crackers (88%), refined white flour tortilla (70%), and elbow macaroni refined-grain cereal (62%) were identified correctly (Figure 1) by low-income adults participating in the interview, their decisions for identifying the foods were based on the product characteristics (Table 4). For instance, refined white flour tortillas were identified correctly based on appearance and either nutrient or ingredient content:

“The tortillas are white, they would be brown if they were whole grain.” (P02 white woman)

“It's got no wheat in it. I can see it.” (V13 black man)

White rice was identified incorrectly by the low-income adults in the interview as whole grain (55%; Figure 1). This is attributed to focusing on the product characteristics and the word “grain” on the packaging (Table 4):

“Whole grain, cause see whole grain itself.” (C02 white woman)

“It looks like the shape of a grain.” (V10 black woman)

“Says right on the box. It's the best.” (V12 white man)

The constructs from the IBM that were not associated with perceived issues with whole-grain consumption among low-income adults were health, sensory, and family influence (Table 5). With regard to attitudes, low-income adults were able to describe reasons for consuming whole-grain foods by understanding the health benefits of consuming whole grains, particularly as they related to overall health, weight management, and heart health (Table 5). They also intended to consume whole grains due to the fiber content of the food (Table 5):

“I use brown rice and beans for fiber nutrients, and satiety, and I'm mostly vegan, working up to 100%.” (C06 white woman)

TABLE 5.

Themes related to factors influencing whole-grain consumption in low-income adults based on the integrative behavioral model constructs

| Construct | Theme and subtheme | Sample quote |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumental attitude: health reasons | Theme: describing health reasons for consuming whole-grain foods | |

| Subtheme: understanding the health benefits of consuming whole-grain foods | “Just to be healthy. Helps you to lose weight and keep you full.” (C10 white woman) | |

| Subtheme: consumption of whole grains due to the nutrient content | “Hopefully more fiber. Whole grain gives you fiber.” (C02 white woman) | |

| Experiential attitude: sensory properties | Theme: Taste and texture do not affect consumption | “Changed 10 years ago, got used to it. Tastes good for me and the kids. Someone gave them white bread and they didn't like it/eat it.” (EH07 Hispanic woman) |

| “They do not, they eat whole grain.” (P02 white woman) | ||

| Injunctive norm: family influence | Theme: family members do not influence whole-grain consumption | “They are on the high side and I don't buy them as often because of the cost.” (C06 white woman) |

| Theme: whole grains are expensive | “Look for cheaper brand or store brand with whole grain.” (P24 white woman) | |

| Perceived behavioral control: cost of whole grains | Theme: whole-grain purchasing behaviors | |

| Personal agency: identification | Theme: indicating ability to view information on food packaging (ingredients, nutrients, and food labels) | “Look at ingredient labels so much. Easy to tell. Look at the label. The ingredient list is small. Whole grains should be prominent especially for people with vision problems.” (E05 white woman) |

| Personal agency: preparation skills | Theme: preparation skills have no effect on whole-grain consumption | “Doesn't because it's not hard. Rice takes longer.” (EH03 black woman) |

However, some low-income adults described that current health status, such as having bariatric surgery or having family members who consume gluten-free diets, limited or completely prevented consumption of whole-grain products:

“I can eat very little because I had gastric sleeve. So mostly protein and vegetables.” (E07 white woman)

“I don't because my daughter has celiac's disease.” (C05 white woman)

Concerning sensory properties, the majority of low-income adults had a positive attitude regarding taste and texture of whole grains, perceiving that they did not affect consumption (Table 5):

“Changed 10 years ago, got used to it. Tastes good for me and the kids. Someone gave them white bread and they didn't like it or eat it.” (EH07 Hispanic woman)

For perceived norms, low-income adults perceived that their family members did not influence their whole-grain consumption (Table 5). Some low-income adults stated that if consumption was problematic in their household, they would incorporate different strategies by adding flavor to the food item:

“They eat whatever I cook so I sneak it in if they don't like them.” (V05 white woman)

For whole-grain preparation, low-income adults indicated that it had no effect on intake, but several described the longer cook time:

“Depends on which food. Rice, hot cereal, and pasta cook differently and longer.” (EH02 black man)

A construct that was a perceived issue to whole-grain consumption was the cost of whole grains (Table 5):

“Can't afford now. More expensive.” (C12 white woman)

While addressing cost, low-income adults also described ways of obtaining affordable whole-grain foods, such as seeking sales, using generic or store brands of whole-grain foods, or using community resources such as food pantries, SNAP, or WIC:

“Don't find too much difference—cereal, bread, pasta [with] WIC. Crackers from food truck.” (V02 other woman)

Identification was not perceived as an issue by the low-income adults, which is in contrast with the outcomes from the quantitative portion of the Whole Grains Detective Challenge:

“Pretty easy, look for packaging ingredients (and) takes extra time, always read.” (E07 white woman)

However, on the contrary, some described how information related to whole grain ingredients was not prominent on food packaging:

“Not as easy as it should be. Not having stuff on package [points to bread]. Whole grain makes it easier.” (C07 white woman)

Discussion

Despite increases of whole-grain foods available in the marketplace (41), prior research indicates that American adults, especially low-income adults, are not meeting the recommended amounts. This study further examined factors that may hinder whole-grain consumption among low-income adults. A potential reason for low intake of whole-grain foods by low-income adults was the misidentification of whole-grain foods. Only 16% of low-income adults were able to identify all 5 whole-grain foods correctly. Common errors included that adults identified popcorn as a refined grain and conversely identified white rice and refined-wheat bread (not whole wheat) as whole-grain foods. This finding was similar to those of other studies of adults who were asked about whole-grain foods (18). For example, in 1 study of mostly older adults, refined-grain bread was incorrectly identified as whole grain (42), whereas in another study of military food service workers, refined-grain cereals were identified as whole grain (17).

Concerning popcorn specifically, health club members, state fair attendees, and WIC participants did not classify the food as whole grain, and only a small percentage of food and nutrition professionals identified the food as whole grain (18). Identification of popcorn as a refined-grain food could potentially impact daily whole-grain consumption. In another study, consumption of popcorn was associated with higher intake of whole grains (2.5 mean servings compared with 0.7 mean servings in nonpopcorn consumers) and increased dietary fiber and magnesium (43). With increased consumer interest in consuming whole-grain foods for health, the popcorn industry could consider labeling or marketing whole-grain ingredients more prominently on their products to improve the ability for consumers to identify it has a whole-grain food. In addition, and more important, the food and labeling industry could devise a standard and required system of clearly, consistently, and prominently labeling all whole-grain foods.

When determining if demographic characteristics (age, gender, race, ethnicity, and education level) were associated with the ability to identify ≥4 whole-grain foods correctly, no significant relations were detected. However, for the identification of a single food such as popcorn, younger age was associated with misidentification. In this study, the popcorn package contained a small icon on the front of the package indicating the product was whole grain, and it was the first ingredient listed on the ingredients list. Although label-reading experience was not assessed, it may explain why the younger age group had lower odds of identifying the popcorn correctly as whole grain because they are also less likely to read food labels. Specifically, 1 study assessing African American adults and label reading found that a higher proportion of older adults aged 50–70 y read nutrition labels than did those aged 20–39 y (44). Similar findings were also reported from 2005–2006 NHANES data, where a lower proportion of 18- to 34-y-old adults used the Nutrition Facts panel, serving size, ingredients list, and health claims compared with those who were 35–54 and 55–85 y old (45).

Proper identification of whole-grain foods remains a barrier among low-income adults. Low-income adults who did not describe identifying the food based on the whole-grain wording or seeking whole-grain ingredients otherwise focused erroneously on sensory characteristics such as color, the presence of specific nutrients in foods, and also not fully describing the areas of the packaging they viewed. This was also observed in another study involving participants’ demonstrated basic understanding of reading packages to identify foods but not referring to the whole-grain information (18).

Lack of processing of the food item and the use of the entire grain kernel were major reasons why adults perceived a food as whole grain or they associated whole-grain status with the food's fiber content (18). Similar outcomes were reported by adults in a focus group who indicated that that they sought the word “fiber” on whole-grain products (37). Other studies indicated trends in identification of whole grains based on the appearance of whole-grain foods; for example, low-income African American women referred to darker color breads that were not whole grain as “wheat” (46). For rice, low-income adults in this study read the word “grain” and assumed this meant whole grain.

Furthermore, this study investigated factors based on IBM to determine potential barriers to eating whole grains in a low-income population that are relevant for designing future interventions to increase whole-grain consumption. Low-income adults cited eating whole grains for favorable health outcomes and the fiber content. Other qualitative studies evaluating behaviors and barriers to whole-grain consumption reported that adults found that whole grains contributed to satiety and contained more nutrients compared with refined-grain products (37). In addition, another study reported that adults primarily consumed whole grains for fiber intake (18). Although most low-income adults did not indicate taste and texture as influences on whole-grain consumption, other researchers reported that taste, flavor, and smell were barriers to whole-grain consumption in a general population (47–49).

For perceived norm, low-income adults perceived that family members did not influence their own whole-grain intake. This is in contrast to other studies that examined the impact of family on whole-grain consumption and found that parents accommodated whole-grain and also refined-grain products in the household based on their child's preferences (37) or reported that having children as picky eaters was a barrier to whole-grain intake (47). In another study, participants cited that spouses were barriers to eating whole-grains foods in the household, primarily due to disliking the food and sensory characteristics (48).

When examining personal agency and perceived control, low-income adults viewed the cost of whole grains as a barrier. This is supported by other studies, including 1 that evaluated factors influencing bread and cereal purchases by low-income African American women where cost of both foods were important factors that influenced purchase (46). Another study found that parents also perceived that whole grains were higher in price compared with refined grains (47). Whereas cost was a perceived barrier to whole-grain food consumption, lack of preparation skills was not perceived as an issue for consuming whole-grain foods by low-income adults. However, other studies have reported preparation and planning time as a barrier (47, 48).

When considering the 2 overarching themes related to IBM, cost and identification were perceived barriers to consuming adequate whole-grain foods among low-income adults. Future considerations for improving identification of whole-grain foods include changing food package designs to better prominently display the words “whole grain” or whole-grain ingredients for consumers in a manner that can be quickly and easily read, especially by those with poor eyesight. Although the Whole Grains Council developed the Whole Grain Stamp program for food companies to incorporate on their packaging, not all whole-grain food products contain this logo (50). Currently, the Whole Grains Council has 3 different stamps for food manufacturers to use on their whole-grain food packages. However, a study found that school food service personnel experienced difficulty interpreting the information on the Whole Grain Stamp (16). This is a potential area for future investigation with consumers to determine how they interpret the stamps and if they are aware of how many daily servings of whole-grain foods are needed to meet the US recommendations, especially if symbols such as the Whole Grain Stamp are listed in grams whereas the DGA recommendations are in ounces. Furthermore, nutrition education outreach could emphasize specific areas to examine on a food package (front of label, ingredients list, and the presence of the Whole Grain Stamp) to help increase self-efficacy in identifying whole-grain foods. Additional research studies may opt to utilize techniques such as eye-tracking technology (51) to determine where and how to best position whole-grain-related information on food packaging. In addition, education and outreach regarding identifying and preparing lower cost versions of whole-grain foods is an area to further intervene with low-income adults.

A strength of this study is that it focused on a low-income population using a mixed methods design to understand perspectives about the facilitators and barriers to consuming whole-grain foods. Limitations of the study include that the results cannot be generalized to other populations, and the data were self-reported.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that low-income consumers’ ability to identify whole-grain foods may be a challenge to consuming adequate amounts. With a current lack of universal whole-grain food labeling in the United States, these results also have implications for policy change as it relates to how and what is communicated on a food package about a whole-grain food. Similar issues perpetuate other countries as well, with a call for a global approach to improving whole-grain consumption (52). Clear and directed messages encouraging whole-grain selection and consumption behaviors related to identification, sensory properties, and cost may be ideal to help all segments of society increase whole-grain intake.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Foodshare Mobile Organization and EastConn for providing permission and support for allowing us to conduct the whole-grains research activity at their sites. The authors’ contributions were as follows—MC and ARM: designed the study; MC: conducted the research and analyzed data; MC and ARM: wrote the manuscript; ARM: had primary responsibility for the final content; and both authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

This research was supported by a USDA Hatch Grant (accession no. 0230817, project no. CONS00907). USDA had no role in the design, analysis, or writing of this article.

Author disclosures: MC and ARM, no conflicts of interest.

Data repository: Data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations used: DGA, Dietary Guidelines for Americans; IBM, integrative behavioral model; SNAP-Ed, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Education Program; TPB, theory of planned behavior; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

References

- 1. Slavin JL, Jacobs D, Marquart L, Wiemer K. The role of whole grains in disease prevention. J Am Diet Assoc 2001;101(7):780–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture. 2015–2020 dietary guidelines for Americans. 8th ed. Washington (DC): US Government Printing Services; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Neil CE, Nicklas TA, Zanovec M, Cho S. Whole-grain consumption is associated with diet quality and nutrient intake in adults: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2004. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110(10):1461–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hiza HA, Casavale KO, Guenther PM, Davis CA. Diet quality of Americans differs by age, sex, race/ethnicity, income, and education level. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113(2):297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aune D, Keum N, Giovannucci E, Fadnes LT, Boffetta P, Greenwood DC, Tonstad S, Vatten LJ, Riboli E, Norat T. Whole grain consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all cause and cause specific mortality: systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ 2016;353:i2716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ye EQ, Chacko SA, Chou EL, Kugizaki M, Liu S. Greater whole-grain intake is associated with lower risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and weight gain. J Nutr 2012;142(7):1304–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Albertson AM, Reicks M, Joshi N, Gugger CK. Whole grain consumption trends and associations with body weight measures in the United States: results from the cross sectional National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2012. Nutr J 2016;15:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. IFIC Foundation. What's your health worth? International Food Information Council Food and Health Survey 2015 [Internet]. 2015[cited January 2019]. Available from: https://foodinsight.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/2015-Food-and-Health-Survey-FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jacobs DR Jr, Andersen LF, Blomhoff R. Whole-grain consumption is associated with a reduced risk of noncardiovascular, noncancer death attributed to inflammatory diseases in the Iowa Women's Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85(6):1606–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reicks M, Jonnalagadda S, Albertson AM, Joshi N. Total dietary fiber intakes in the US population are related to whole grain consumption: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2009 to 2010. Nutr Res 2014;34(3):226–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lin BW, Yen ST. The U.S. grain consumption landscape: who eats grain, in what form, where, and how much? Hyattsville (MD): US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mann KD, Pearce MS, McKevith B, Thielecke F, Seal CJ. Low whole grain intake in the UK: results from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey Rolling Programme 2008–2011. Br J Nutr 2015;113(10):1643–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Public Health England. The Eatwell Guide: helping you eat a healthy balanced diet [Internet]. 2016[cited January 2019]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/551502/Eatwell_Guide_booklet.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feruzzi MG, Jonnalagadda SS, Liu S, Marquart L, McKeown N, Reicks M, Riccardi G, Seal C, Slavin J, Thielecke F et al.. Developing a standard definition of whole-grain foods for dietary recommendations: summary report of multidisciplinary expert roundtable discussion. Adv Nutr 2014;5(2):164–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Korczak R, Marquart L, Slavin JL, Ringling K, Chu Y, O'Shea M, Jacques P et al.. Thinking critically about whole-grain definitions: summary report of an interdisciplinary roundtable discussion at the 2015 Whole Grains Summit. Am J Clin Nutr 2016;104:1508–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chu YL, Orsted M, Marquart L, Reicks M. School foodservice personnel's struggle with using labels to identify whole-grain foods. J Nutr Educ Behav 2012;44(1):76–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Warber JP, Haddad EH, Hodgkin GE, Lee JW. Foodservice specialists exhibit lack of knowledge in identifying whole grain products. J Am Diet Assoc 1996;96:796–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marquart L, Pham AT, Lautenschlager L, Croy M, Sobal J. Beliefs about whole-grain foods by food and nutrition professionals, health club members, and special supplemental nutrition program for women, infants, and children participants/state fair attendees. J Am Diet Assoc 2006;106(11):1856–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nansel TR, Laffel LM, Haynie DL, Mehta SN, Lipsky LM, Volkening LK, Butler DA, Higgins LA, Liu A. Improving dietary quality in youth with type 1 diabetes: randomized clinical trial of a family-based behavioral intervention. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015;12:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Radford A, Langkamp-Henken B, Hughes C, Christman MC, Jonnalagadda S, Boileau TW, Thielecke F, Dahl WJ. Whole-grain intake in middle school students achieves dietary guidelines for Americans and MyPlate recommendations when provided as commercially available foods: a randomized trial. J Acad Nutr Diet 2014;114(9):1417–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Siega-Riz AM, El Ghormli L, Mobley C, Gillis B, Stadler D, Hartstein J, Volpe SL, Virus A, Bridgman J; HEALTHY Study Group. The effects of the HEALTHY study intervention on middle school student dietary intakes. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schaffer-Lequart C, Lehmann U, Ross AB, Roger O, Eldridge AL, Ananta E, Bietry MF, King LR, Moroni AV, Srichuwong S et al.. Whole grain in manufactured foods: current use, challenges, and the way forward. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2015;57(8):1562–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aggarwal A, Monsivais P, Cook AJ, Drewnowski A. Positive attitude toward healthy eating predicts higher diet quality at all cost levels of supermarkets. J Acad Nutr Diet 2014;114(2):266–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tuuri G, Cater M, Craft B, Bailey A, Miketinas D. Exploratory and confirmatory factory analysis of the Willingness to Eat Whole Grains Questionnaire: a measure of young adults’ attitudes toward consuming whole grain foods. Appetite 2016;105:460–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fishbein M, Azjen I. Predicting and changing behavior: the Reasoned Action. Hove (UK):Psychology Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fishbein M, Yzer MC. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Communication Theory 2003;13(2):164–83. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fishbein M, editor. A reasoned action approach: some issues, questions, and clarifications. Hillsdale (NJ): Erlbaum; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Glanz K, Basil M, Maibach E, Goldberg J, Snyder D. Why Americans eat what they do: taste, nutrition, cost, convenience, and weight control concerns as influences on food consumption. J Am Diet Assoc 1998;98(10):1118–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim K, Reicks M, Sjoberg S. Applying the theory of planned behavior to predict dairy product consumption among older adults. J Nutr Educ Behav 2003;35:294–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pawlak R, Malinauskas B. Predictors of intention to eat 2.5 cups of vegetables. J Nutr Educ Behav 2008;40(6):392–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zoellner J, Krzeski E, Harden S, Cook E, Allen K, Estabrooks PA. Qualitative application of the theory of planned behavior to understand sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among adults. J Acad Nutr Diet 2012;112:1764–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Branscum P, Lora KR. Development and validation of an instrument measuring theory-based determinants of monitoring obeseogenic behaviors of preschoolers among Hispanic mothers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13(6):554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Montaño DE, Kaspryzk D, editors. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavior model. San Francisco (CA): Jossey-Bass; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Foodshare. About Foodshare [Internet]. 2018[cited January 2019]. Available from: http://site.foodshare.org/site/PageServer?pagename = 2017_about. [Google Scholar]

- 36. McMackin E, Dean M, Woodside JV, McKinley MC. Whole grains and health: attitudes to whole grains against a prevailing background of marketing and promotion. Public Health Nutr 2013;16(4):743–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Burgess-Champoux T, Marquart L, Vickers Z, Reicks M. Perceptions of children, parents, and teachers regarding whole-grain foods, and implications for a school-based intervention. J Nutr Educ Behav 2006;38(4):230–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kuznesof S, Browleen I, Moore C, Richardson DP, Jebb SA, Seal CJ. WHOLEheart study participant acceptance of wholegrain foods. Appetite 2012;59(1):187–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rosen RA, Burgess-Champoux TL, Marquart L, Reicks MM. Associations between whole-grain intake, psychosocial variables, and home availability among elementary school children. J Nutr Behav 2012;44(6):628–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Whole Grains Council. Whole grain statistics [Internet]. 2019[cited January 2019]. Available from: https://wholegrainscouncil.org/newsroom/whole-grain-statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Violette C, Kantor MA, Ferguson K, Reicks M, Marquart L, Laus MJ, Cohen N. Package information used by older adults to identify whole grain foods. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr 2016;35(2):146–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grandjean AC, Fulgoni VL, Reimers KJ, Agarwal S. Popcorn consumption and dietary and physiological parameters of US children and adults: analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002 dietary survey data. J Am Diet Assoc 2008;108(5):853–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Satia JA, Galanko JA, Neuhouser ML. Food nutrition label use is associated with demographic, behavioral, and psychological factors and dietary intake among African Americans in North Carolina. J Am Diet Assoc 2005;105(3):392–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ollberding NJ, Wolf RL, Contento I. Food label use and its relation to dietary intake among US adults. J Am Diet Assoc 2010;110:1233–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chase K, Reicks M, Jones JM. Applying the theory of planned behavior to promotion of whole-grain foods by dietitians. J Acad Nutr Diet 2003;103(12):1639–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nicklas TA, Jahns L, Bogle ML, Chester DN, Giovanni M, Klurfield DM, Laugero K, Liu Y, Lopez S, Tucker KL. Barriers and facilitators for consumer adherence to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans: The HEALTH study. J Acad Nutr Diet 2013;113(10):1317–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Croy M, Marquart L. Factors influencing whole-grain intake by health club members. Top Clin Nutr 2005;20(2):166–76. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kantor LS, Variyam JN, Allshouse JE, Putnam JJ, Lin BH. Choose a variety of grains daily, especially whole grains: a challenge for consumers. J Nutr 2001;131(2):473S–86S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Whole Grains Council. Whole grain stamp [Internet]. 2017[cited January 2019]. Available from: https://wholegrainscouncil.org/whole-grain-stamp. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Scherr RE, Laugero KD, Graham DJ, Cunningham BT, Jahns L, Lora KR, Reicks M, Mobley AR. Innovative techniques for evaluating behavioral nutrition interventions. Adv Nutr 2017;8(1):113–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Seal CJ, Nugent AP, Tee ES, Thielecke F. Whole-grain dietary recommendations: the need for a unified global approach. Br J Nutr 2016;115(11):2031–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]