Abstract

This work is focused on the photocatalytic activities of undoped ZnO, Co (1%) doped ZnO (CZO) and In (1%) doped ZnO (IZO) thin films grown on flexible PEI (Polyetherimide) substrate by spray pyrolysis. The photodegradation of crystal violet dye was investigated under UV and sunlight irradiations. Doping and excitation energy effects on photocatalytic efficiencies are discussed. All ZnO thin films show high photocatalytic efficiency up to 80% under either UV or sunlight irradiations for 210 min. However, CZO has the higher photocatalytic performance under UV irradiation. While, the photodegradation efficiency of IZO was enhanced under sunlight irradiation due to the narrowing of its optical gap. These results are discussed based on structural, morphological and optical investigations. The photocatalytic stability of ZnO films was studied as well. So, after three photocatalysis cycles, all ZnO thin films still effective. The obtained results are promising for the use of doped ZnO/PEI as talented photocatalysts for applications in large surfaces with various geometries for photodegradation of hazardous pollutants.

Keywords: Materials science, Nanotechnology, Materials testing, Nanostructured material, ZnO thin films, Flexible substrate, Crystal violet dye, Photocatalysis, Photostability

1. Introduction

In recent decades, water purification becomes one of the popular environmental challenges. Organic dyes are the major class of pollutants in the wastewater coming from textile, paper printing, and plastic manufacturing processes. Photocatalysis is a promising approach in regard to the removal processes of these pollutants [1, 2, 3]. Notably, the use of the semiconductors as photocatalysts is one of the wide interest axes to resolve environmental pollution problems [4, 5]. A various semiconductor such as TiO2, ZnO, and SnO2 [6, 7, 8, 9, 10] are presented as promising photocatalysts. TiO2 is the most applied one [11, 12]. However, ZnO has been proposed as an alternative photocatalyst to TiO2 since it has been found to be more economic [13] safe and biocompatible for most environmental applications [6, 14]. In addition, it exhibits higher absorption efficiency across a large fraction of the solar spectrum when compared to TiO2 [15]. Many researchers reported on the use of ZnO powder for the photocatalytic activity [16, 17, 18, 19, 20]. However, more attention has been focused on the use of thin films [21, 22, 23] to overcome several practical problems arising from the use of powder such as the difficulty separating the insoluble catalyst from the suspension, as well as recycling of the catalyst powders. The photocatalytic activities of ZnO thin films deposited on a glass substrate and on flexible polymer substrate have been reported [24, 25]. However, the photocatalytic performance of ZnO thin films deposited on other substrates is somewhat studied. In addition, Alessandro Di Mauro et al [26] reported that ZnO thin films deposited on PMMA flexible substrate have a comparable photocatalytic activity to the ZnO film deposited on Si substrate under UV light irradiation. Thus, we are interested in the use of ZnO thin films, grown on flexible PEI (Polyetherimide) substrate as photocatalysts [27, 28], since PEI has better mechanical properties compared to glasses. This makes the elaborated photocatalysts suitable to be used in various geometries.

Furthermore, introduced impurity levels by doping with various elements such as Cu [29], Fe [30], Ni [31], Co [32], C [33] and In [34] generated lattice defects can have a significant influence on the photocatalytic performance of materials.

In previous work [35], it is found that doping ZnO thin films by Co, or In changed its physical properties. Hence, in this work, our research efforts are focused on the investigation of the effect of Cobalt and Indium doping on the photocatalytic efficiency of ZnO films deposited on a flexible substrate. The photocatalytic activities were tested for degradation of crystal violet under UV and sunlight irradiations in similar experimental conditions. The photocatalytic stability of the studied films is investigated as well. All obtained results are correlated and the enhanced photocatalytic activity is interpreted based on structural, morphological and optical investigations.

2. Experimental

2.1. Preparation of ZnO thin films and characterization techniques

ZnO, IZO (In (1%) doped ZnO) and CZO (Co (1%) doped ZnO) were grown by the spray pyrolysis technique on PEI substrate at T = 250 °C. We used zinc acetate dihydrate (Zn (CH3COO)2. 2H2O) dissolved in distilled water and propanol mixture [36]. The doping sources are CoCl2 and InCl3for Co and In respectively with 1% doping percentage. More details were reported in previous work [35].

The structural characterization is carried out by X-ray diffractometer (Analytical X Pert PROMPT). Cukα radiation (λ = 1.5406Å) was used as an excitation source. The morphological properties are studied by AFM spectroscopy. The optical parameters were determined using a Shimadzu UV 3100 UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer in the wavelength range from 300 to 2000 nm. As well, PL measurements are carried out at room temperature using Perkin Elmer LS-55 Luminescence/Fluorescence spectrophotometer with 325 nm as a wavelength excitation.

2.2. Photocatalysis test

The photocatalytic activity was checked in the process of Crystal violet (CV) photodegradation with an initial concentration of C0 = 12.5 mg/L. The irradiation was carried out using an UV-lamp (Black-Ray B 100WUV-lamp, V-100AP series) with a wavelength of 365 nm and sunlight irradiation. Before illumination, the dispersion was magnetically stirred for 60 min (in the dark), in order to ensure an adsorption equilibrium between the sample surface and the organic dye [37]. The photodegradation duration is chosen equal to 210 min. A detailed description of the photocatalytic reactor was reported in earlier studies [27, 38].

The concentration of CV was measured by a UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Shimadzu UV-vis spectrophotometer model 160A). Therefore, the CV dye photodegradation efficiency () was calculated at the maximal absorption wavelength of CV solution λ max = 578 nm as follows [39]:

| (1) |

where C is the actual dye concentration of CV at time t of the reaction and C0 is the initial dye concentration and C/C0 = A/A0 (A is the absorbance of the CV dye solution).

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Physical investigations

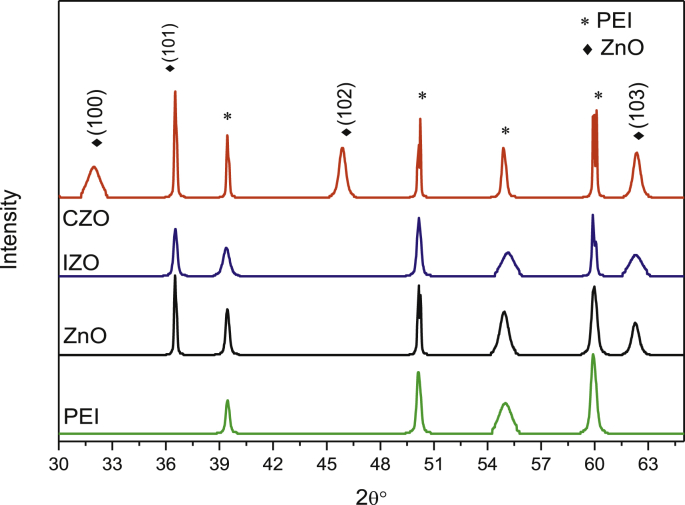

Fig. 1 shows the XRD patterns of ZnO, IZO (In (1%) doped ZnO) and CZO (Co (1%) doped ZnO) thin films, as well as PEI substrate. The diffraction peaks matched well the hexagonal wurtzite structure of ZnO according to the (JCPDS 36–1451) with (101) preferred orientation. Besides, XRD spectra revealed the presence of peaks corresponding to the PEI substrate.

Fig. 1.

XRD patterns of ZnO, IZO, CZO thin films and PEI substrate.

The lattice parameters a and c for ZnO/PEI thin films were calculated from the XRD patterns by using the following equation:

| (2) |

where h, k, and l are the Miller indices of the planes and dhkl are the interplanar spacing.

The lattice parameters, computed using Eq. (2), are shown in Table 1. By comparing the obtained values with the standard lattice volume, we can note that CZO film has the volume closer to that of bulk ZnO. Thus, it seems the most relaxed lattice. This means an improvement in the crystalline quality of films, and indicates the substitution of Zn2+ by Co2+ ions [40, 41, 42]. In fact, since the ionic radius of Co2+ (0.072 nm) is close to that of Zn2+ (0.074 nm); it presents large solubility in the ZnO matrix [43].

Table 1.

XRD parameters of undoped and doped ZnO thin films deposited on PEI substrate.

| ZnO | IZO | CZO | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a(Å) | 3.247 | 3.249 | 3.257 |

| c(Å) | 5.200 | 5.201 | 5.214 |

| V(Å3) | 46.600 | 46.666 | 47.014 |

| D (nm) | 83.3 | 41.7 | 83.4 |

| δ (10−4nm−2) | 1.44 | 5.76 | 1.44 |

| ζ (10−4) | 13 | 27 | 13 |

| S (m2g−1) | 0.124 | 0.248 | 0.124 |

| RMS (nm) | 20,4 | 6.9 | 20.5 |

a0=b0= 3.249 (Å), c0= 5.206 (Å) and V0= 47.63 (Å3) From JCPDS 36-1451.

Furthermore, from XRD patterns, we can determine the microstructural parameters such as the crystallite size (D), the micro-strain (ζ) and the dislocation density (δ) using the following expressions (3–5) [44]:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

The obtained values show that the crystallite size (D) (Table 1) is not affected by doping with Co. This is probably due to the substitution between Co2+ ions and Zn2+ ions in ZnO lattice [45]. Moreover, for IZO films the crystallite size decreases, this is can be explained by the incorporation of In3+ ions in the interstitial sites of the ZnO lattice [46]. This hypothesis can be supported by the high microstrain (ζ) value (27.10−4), calculated from (Eq. (5)).

Assuming that the particles have a spherical shape, we can estimate the specific surface area from the crystallite size, using formula (6 and 7) [47]:

| (6) |

| (7) |

where ρ is the density of the particles, M is the molar weight of substance (M = 81.38 g/mol), n is the number of formula units in the unit cell (n = 2 for ZnO according to the JCPDS 36–1451 card), V is the volume of the unit cell, and N is Avogadro's number.

The obtained specific surface area values are listed in Table 1. The values show that the IZO has the larger specific surface area, which is promising to high photocatalytic efficiency. This will be confirmed in the following sections.

The presence of defects due to various elements doping will affect the morphological and optical properties of ZnO thin films. In particular, the change of crystallite size and lattice strain will have a profound impact on the PL spectra of ZnO thin films, which will be discussed later.

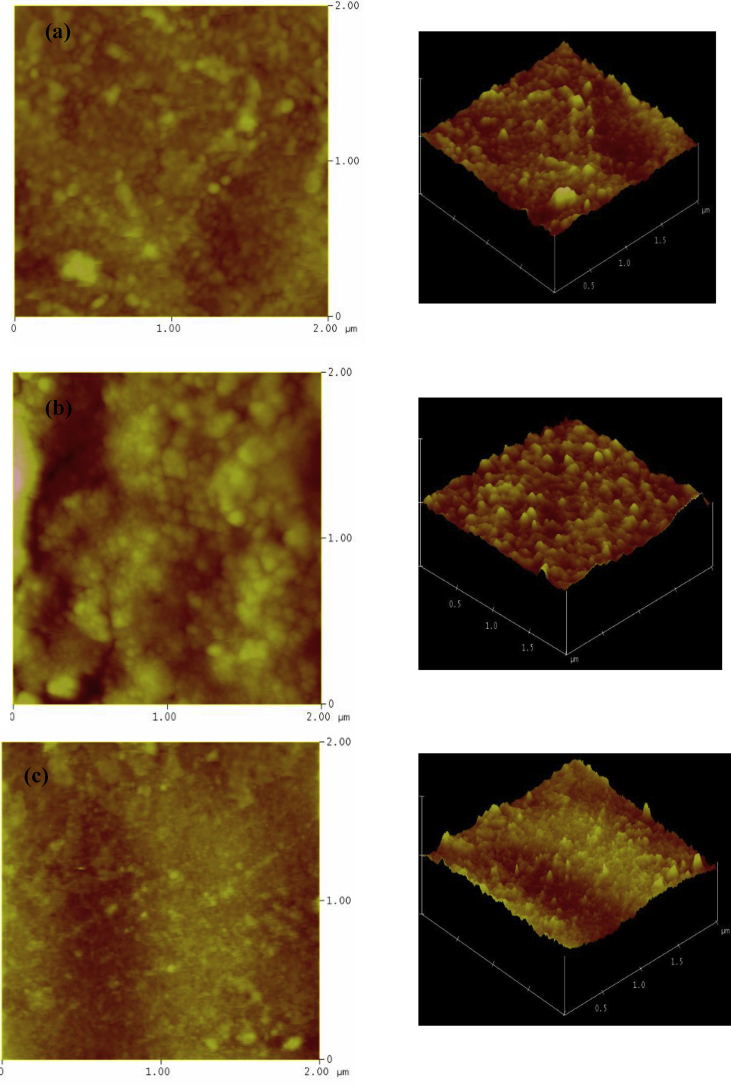

The surface morphology of all deposited ZnO thin films was estimated by AFM. This study gives information about the surface topography and the average roughness (RMS) values. Notably, the photocatalytic activities of thin films depend on surface roughness.

Fig. 2 shows 3D and 2D topographic views of all films (2 × 2μm). From images especially 3D, it can be seen that all film surfaces are rough, whereas IZO surface is the smoother one. CZO thin films have densely packed grains dispirited on all surface with hollow zones showing rough surface. The RMS values are found to range between 6.9 nm and 20.5 nm (Table 1). As can be seen, the introduction of indium on the ZnO lattice causes a decrease of surface roughness up to 6.9 nm. This is related to the average crystallite size.

Fig. 2.

2D and 3D topographic AFM images of ZnO films:(a)ZnO,(b) CZO and (c) IZO.

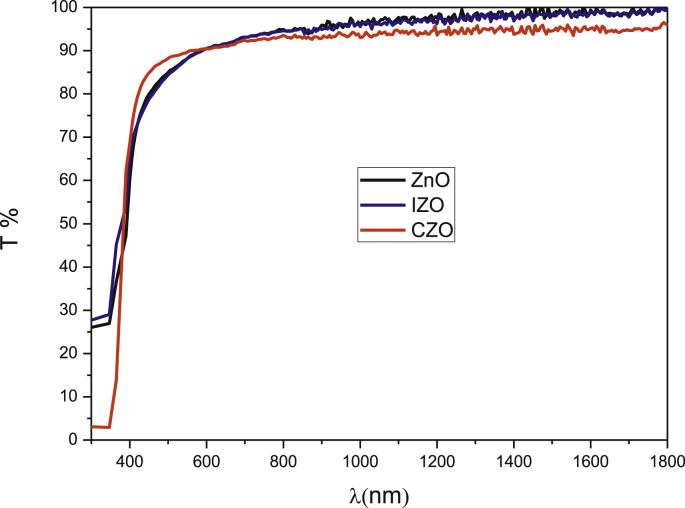

Using a UV–Vis–NIR spectrometry, we can study the optical properties of the ZnO films in the wavelength range from 300 to 1800 nm. The transmittance spectra of ZnO, IZO and CZO thin films are shown in Fig. 3. All films are absorbers in the UV region and they exhibit a high transmission (T (%) ≥ 85%) in visible and NIR regions (400–1800 nm). Such transparency may be due to low scattering and absorption losses. The elaborated ZnO thin films exhibit sharp absorption edges in the ultraviolet region (360–400 nm). From this region, we can determine the optical band gap values using Tauc's relation (Eq. (8)) for allowed direct transitions [48]:

| (8) |

Fig. 3.

Transmittance spectra of ZnO, CZO, IZO thin films.

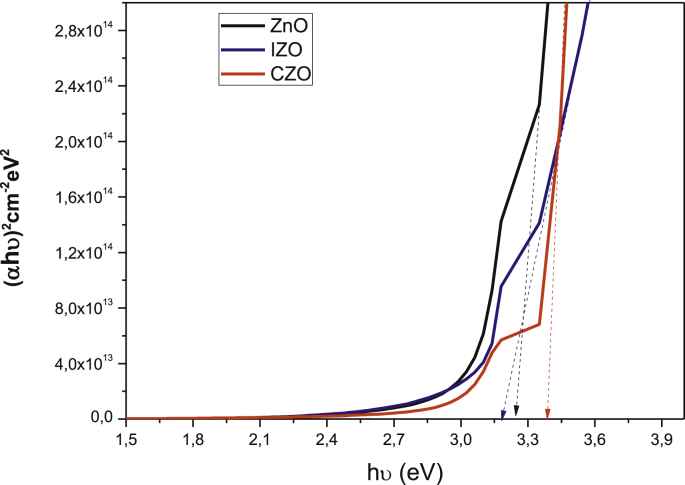

The optical band gap energy was calculated by extrapolation of the linear part of (αhν)2 vs hν plot, as shown in Fig. 4. The obtained gap energy values are 3.22, 3.33 and 3.18 eV for undoped ZnO, CZO and IZO thin films respectively.

Fig. 4.

Optical band gap energy estimation of ZnO, IZO and CZO thin films.

The photoluminescence spectroscopy was used to deduce the photo-active centers in ZnO thin films. These photo-active centers are really the defects whose affect the electron-hole recombination. So, Controlling of intrinsic defects is of paramount importance in applications of ZnO.

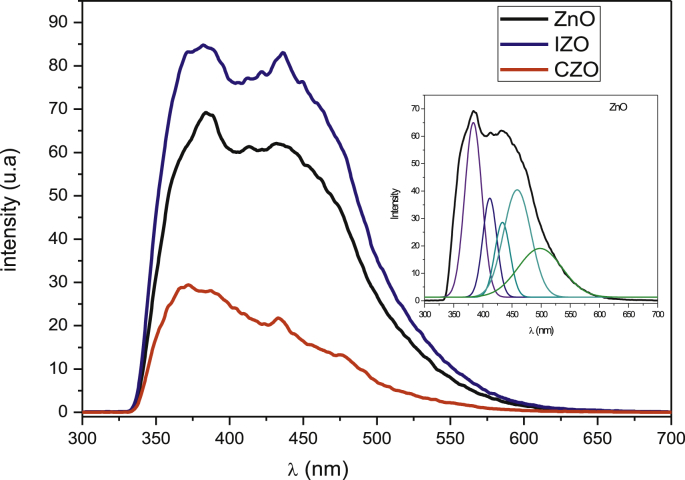

The PL spectra of ZnO, IZO and CZO thin films, measured at room temperature with an excitation wavelength of 325 nm, were shown in Fig. 5. Firstly, we note a decrease of PL intensity after doping with Co which indicates that CZO thin film has low electron-holes recombination rate, thus it may exhibit better photocatalytic activity than ZnO and IZO ones.

Fig. 5.

PL spectra of all ZnO thin films and deconvolution of undoped ZnO spectra as an example (inset).

As can be seen in all ZnO thin films, the emission is mainly categorized as near band edge emission in the UV region and some emissions in the visible range. Usually, ZnO has six kinds of defects, namely oxygen vacancies (VO), oxygen interstitials (Oi), oxygen antisites (ZnO), zinc vacancies (VZn), zinc interstitials (Zni), and zinc antisites (OZn) [49]. From the deconvolution using Gaussian analysis, shown in the inset of Fig. 5, we can determine the different defects energy states. The photoluminescence (PL) spectra of all ZnO thin films, typically show emission bands in the ultraviolet (UV) and visible (violet, blue, blue-green- and green) regions. Firstly, the UV emission is usually considered as the characteristic emission of ZnO [50] and attributed to the near band–edge transition or excitonic recombination.

It is suggested that the origin of the violet emission at λ ∼410 nm (3.02 eV) is due to the transitions from conduction band (CB) to the holes localized at defect level associated with zinc vacancy (VZn) [51]. The blue luminescence bands situated in (430–480) nm (2.8–2.68 eV) domain are due to transitions from extended donor Zni states and the holes in the valence band [52]. The blue-green emissions [480–510 nm] may be due to the transition from the oxygen inertial (Oi) and zinc antisites (OZn) to the valence band [53]. The visible green emissions peaks located at λ > 520 nm are observed only for CZO and IZO thin films (Table 2). This emission has been widely reported as oxygen vacancies. Therefore, the doping element causes a loss of oxygen and thus the formation of oxygen vacancies (VO). Furthermore, intrinsic oxygen non-stoichiometry leads to the presence of a large number of oxygen defect sites in doped ZnO surface which may serve as electron trapping sites making it suitable for efficient photocatalytic applications [54, 55, 56].

Table 2.

Charachetreistics of photoluminescence peaks: positions and energy.

| ZnO | IZO | CZO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak 1 UV |

Position (nm) Energy (eV) |

383 3.239 |

385 3.222 |

366/390 3.39/3.18 |

| Peak 2 Violet |

Position (nm) Energy (eV) |

412 3.011 |

408 3.04 |

411 3.018 |

| Peak 3 Blue |

Position (nm) Energy (eV) |

432/460 2.871/2.697 |

430/462 2.885/2.685 |

430/463 2.885/2.68 |

| Peak 4 blue- Green | Position (nm) Energy (eV) |

495 2.51 |

504 2.461 |

- |

| Peak 5 Green |

Position (nm) Energy (eV) |

- | 564 2.22 |

526 2.358 |

3.2. Photocatalytic activities

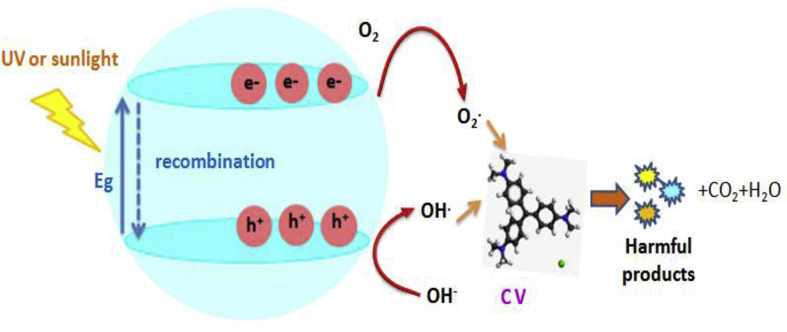

The photocatalytic activities of all ZnO thin films are evaluated by the Crystal violet (CV) photodegradation under UV and sunlight irradiations for 210 min. The principle of photocatalysis is the irradiation of ZnO with energy equal to or higher than the energy band gap, which causes promotion of an electron from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB). The combination of the positive hole (h+) with water and/or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) produces hydroxyl radicals (•OH). Simultaneously, oxygen molecules absorbed on the photocatalyst are reduced by the electrons in the conduction band, and produce a superoxide radical anion (O2•−) [57, 58]. The generated •OH and O2•− are all powerful oxidant for the degradation of organic compounds. Incorporation of doping ions into ZnO lattice will create more electrons and holes traps, which fasten the charge carriers and thus suppress the recombination of photoinduced electrons and holes, leading to the improvement of the photocatalytic activity [59, 60]. The mechanism is more detailed in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Photocatalytic process of CV degradation using ZnO catalysts.

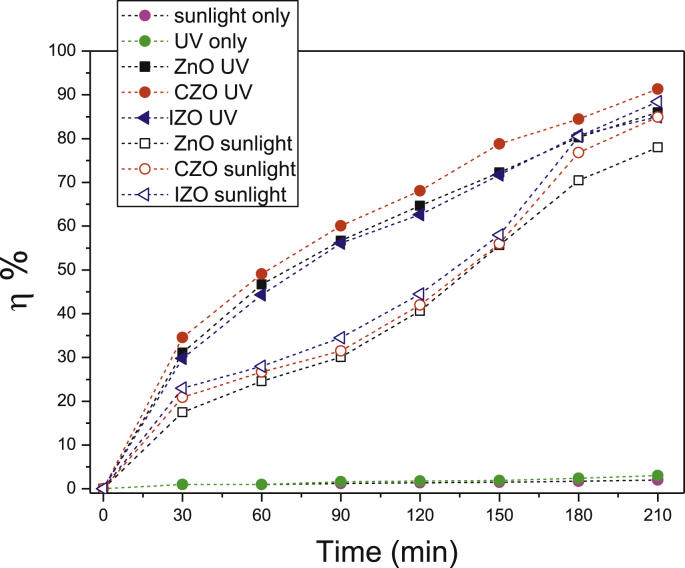

The photodegradation efficiency, computed from Eq. (1), was plotted versus the irradiation time, for ZnO thin films under UV and sunlight irradiations (Fig. 7). Firstly, preliminary experiments were carried out without photocatalysts, the CV solution was exposed to UV or sunlight irradiation. The results show that the photodegradation efficiencies are around (3%) and (2%) for UV and sunlight irradiation, respectively. Insignificant degradation was observed. On the one hand, we note that ZnO thin films under UV and sunlight have different photocatalytic activities. Under UV irradiation after 210 min, the photodegradation efficiency is 86%, 91.3% and 85% for ZnO, CZO and IZO, respectively. However, after the same time under sunlight irradiation, the photodegradation efficiency is 78%, 85% and 88.5% for ZnO, CZO and IZO, respectively.

Fig. 7.

The photodegradation efficiency of undoped and (In, Co) doped ZnO thin films under UV and sunlight irradiations.

In general, the photocatalytic activity was sensitive to the crystalline, surface OH groups, specific surface area and the roughness of the photocatalyst surface. Hence, the CZO has the higher photocatalytic performance under UV irradiation. This result can be attributed to the position of dopants into the ZnO lattice. As demonstrated by DRX, the Co2+ substituted Zn2+ whereas the In3+ is localized on the interstitial site which causes crystal defects. Many results [30,60] approve that the dopants localized in interstitial sites would act as trapping or recombination centers for photo-excited electrons and holes [55]. Furthermore, it causes a slight decrease in the photocatalytic activity as seen in IZO thin films. Besides, some works of literature [61,62] have already reported that smaller grain size has a higher-population of surface defects for the enhanced defect emission relative to PL emission. Indeed, we have noticed an obvious enhancement in PL emission in IZO. Additionally, the concentration of defects on the surface of the catalyst can also make a difference in photocatalytic activity [63]. Moreover, CZO film has a good crystallinity combined with a high surface roughness, which improves its photocatalytic performance compared to ZnO and IZO ones [64]. This enables sample absorption in the visible range of the solar spectrum [39]. In addition, IZO has the largest specific area. This result reveals that all ZnO thin films show promising photocatalytic activities under UV as well as visible light comparable to ZnO thin films deposited on glass substrate.

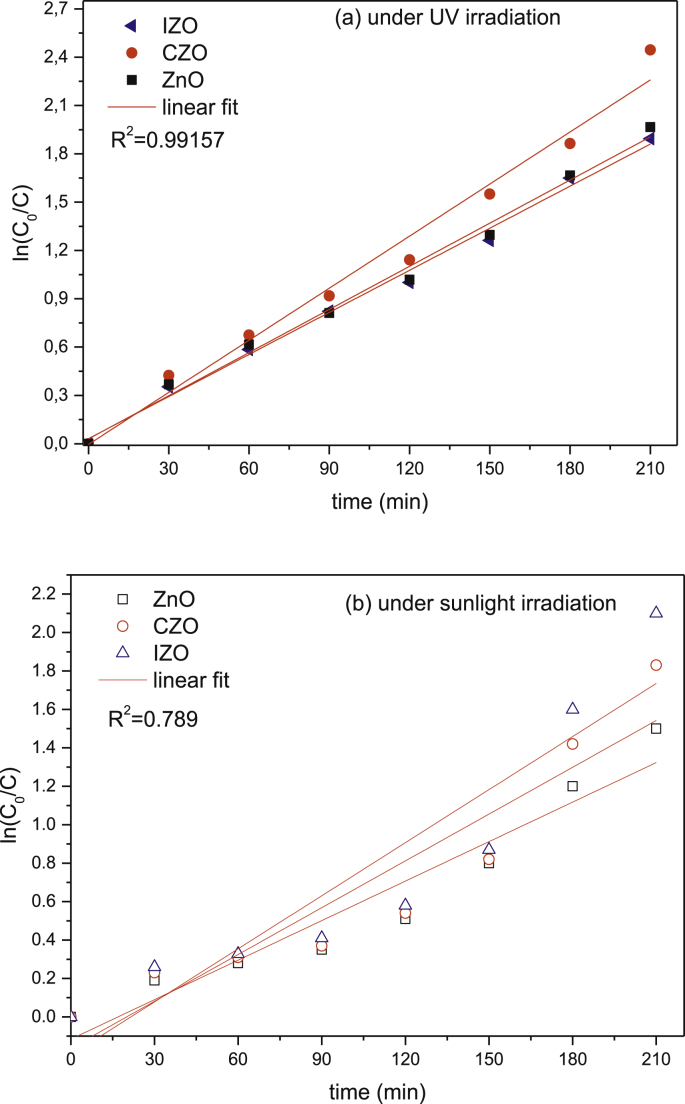

On the other hand, Fig. 7 shows a difference in photodegradation kinetics of CV degradation using undoped and (Co, In) doped ZnO thin films. Furthermore, it is ordered to quantify the photodegradation kinetics of the CV; we used the formula of a pseudo first order process studied by Langmuir and Hishelwood. It is reported [17] that the rate of photocatalysis of CV dye by irradiated ZnO thin films was investigated via pseudo-first-order kinetics (Fig. 8):

| (9) |

where kapp is the apparent rate constant of the first-order reaction (min−1).

Fig. 8.

Plot of versus irradiation time for ZnO, CZO and IZO thin films, under (a) UV and (b) sunlight irradiation.

A plot of (Eq. (9)) is given in Fig. 8 it exhibits a straight line; the slope equals the apparent first-order rate constant kapp. Also, we determined the half-life value (t1/2) of all films and the obtained values are listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Kinetic analysis: kinetic constants and t1/2 of all ZnO thin films

| Samples | kapp(min−1) | t1/2(min) |

|---|---|---|

| ZnO (UV) | 0.009 | 77 |

| CZO (UV) | 0.011 | 63 |

| IZO (UV) | 0.008 | 87 |

| ZnO (sunlight) | 0.007 | 99 |

| CZO (sunlight) | 0.008 | 86.6 |

| IZO (sunlight) | 0.009 | 77 |

Fig. 8 shows that the best photocatalytic activities were found using CZO photocatalyst under UV light, with the rate constant (kapp) and half-time (t1/2) of 0.011min−1 and 63 min respectively.

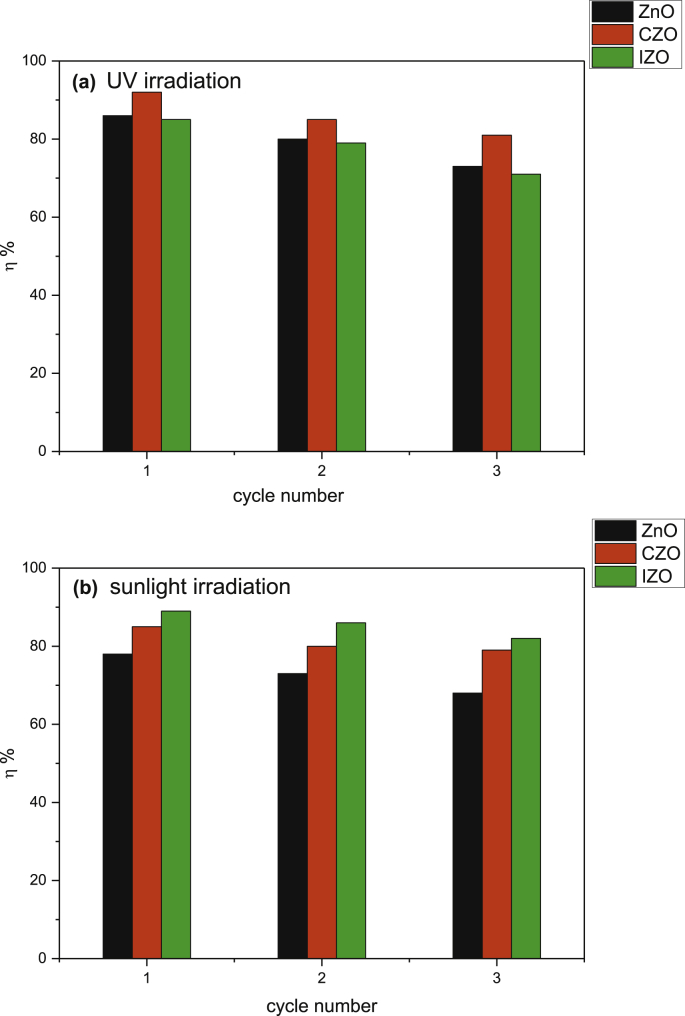

The kinetic study revealed that CZO thin film is a promising photocatalyst for the degradation of CV pollutant. Therefore, the photocatalytic stability of all ZnO was investigated by repeating the photodegradation measurements up to for three times. Fig. 9 shows the photodegradation efficiency of all films under UV and sunlight irradiations for 210 min after using them for three cycles. Indeed, under UV irradiation after three cycles, the photodegradation efficiencies are 73%, 81% and 71% for ZnO, CZO, and IZO respectively. Furthermore, under sunlight irradiation, the photodegradation efficiency achieved 68%; 79% and 82% for ZnO, CZO, and IZO respectively. The measurements clearly show that after three processes, the photo-degradation activity is slightly reduced (11%). Thus the investigated samples exhibit a negligible drop of their photocatalytic performances, suggesting that these films were reusable and retain good photodegradation efficiency. Moreover, this indicates a possibility for application of ZnO thin films as photocatalysts in wastewater treatments, mainly IZO under sunlight irradiation.

Fig. 9.

The photodegradation efficiency through three consecutive photocatalysis versus cycle number: under (a) UV irradiation and (b) sunlight irradiation.

4. Conclusion

This work clearly shows a high photocatalytic performance of ZnO thin films deposited on PEI flexible substrate under either UV or sunlight irradiation. The effects of doping elements on photocatalytic activities of ZnO thin films are discussed. CZO thin films have higher photocatalytic activities under UV irradiation due to its good crystallinity combined with its high surface roughness. However, IZO has higher photocatalytic activities under sunlight irradiation due to its smaller band gap and its large specific area. In addition, all ZnO thin films retained high photodegradation efficiency even after three photocatalytic cycles, which is favorable for potential environmental and industrial applications. Furthermore, the obtained results confirm that ZnO thin films deposited on PEI flexible substrate are potential candidates as a photocatalyst for UV and solar photodegradation process of persistent organic pollutants. Besides, based on our investigations we can affirm that it is possible and easy to synthesize ZnO thin films on PEI flexible substrate (ZnO/PEI) as talented photocatalysts for applications in large surfaces with various geometries for photodegradation of hazardous pollutants.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Samir Guermazi: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Hajer Guermazi: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Mosbah Amlouk: Conceived and designed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Sameh Ben Ameur: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Haythem Belhadj Ltaief: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Benoit Duponchel: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Gérard Leroy: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This work was supported by Tunisian Ministry of High Education and Scientific Research.

Competing interest statment

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

Authors gratefully thank the financial support of the Tunisian Ministry of High Education and Scientific Research.

References

- 1.Subramanian A.P., Jaganathan S.K., Manikandan A., Pandiaraj K.N., Gomathi N., Supriyanto E. Recent trends in nano-based drug delivery systems for efficient delivery of phytochemicals in chemotherapy. RSC Adv. 2016;6:48294–48314. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godlyn Abraham A., Manikandan A., Manikandan E., Jaganathan S.K., Baykal A., Sri Renganathan P. Enhanced opto-magneto properties of Ni x Mg1–x Fe2O4 (0.0 ≤ x ≤ 1.0) ferrites nano-catalysts. J. Nano. Opto. 2017;12:1326–1333. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meenatchi B., Renuga V., Manikandan A. Size-controlled synthesis of chalcogen and chalcogenide nanoparticles using protic ionic liquids with imidazolium cation. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2016;33:934–944. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hisatomi T., Kubota J., Domen K. Recent advances in semiconductors for photocatalytic and photo electrochemical water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:7520–7535. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60378d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thennarasu G., Sivasamy A. Metal ion doped semiconductor metal oxide nanosphere particles prepared by soft chemical method and its visible light photocatalytic activity in degradation of phenol. Powder Technol. 2013;250:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.S Siddhapara K., Shah D.V. Study of photocatalytic activity and properties of transition metal ions doped nanocrystalline TiO2 prepared by sol-gel method. Ann. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar K., Chitkara M., Sandhu I.S., Mehta D., Kumar S. Photocatalytic, optical and magnetic properties of Fe-doped ZnO nanoparticles prepared by chemical route. J. Alloy. Comp. 2014;588:681–689. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazloom J., Ghodsi F.E., Golmojdeh H. Synthesis and characterization of vanadium doped SnO2 diluted magnetic semiconductor nanoparticles with enhanced photocatalytic activities. J. Alloy. Comp. 2015;639:393–399. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Selvam N., Sagaya C., Manikandan, Kennedy A., John L., Vijaya, Judith J. Comparative investigation of zirconium oxide (ZrO2) nano and microstructures for structural, optical and photocatalytic properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2013;389 doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manikandan A., Durka M., Seevankan K., Arul Antony S. A novel one-pot combustion synthesis and opto-magnetic properties of magnetically separable spinel MnxMg1-xfe2O4 (0.0<x<0.5) nanophotocatalysts. J. Supercond. Nov. Magnetism. 2015;28:1405–1416. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adachi T., Latthe Sanjay S., Gosavi Suresh W., Roy Nitish, Suzuki N., Kazuki Kato H., Katsumata Ken-ichi, Nakata Kazuya, Furudate Manabu, Inoue Tomohiro, Kondo Takeshi, Yuasa Makoto, Fujishima Akira, Terashima Ch. Photocatalytic, superhydrophilic, self-cleaning TiO2 coating on cheap, light-weight, flexible polycarbonate substrates. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;458:917–923. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi K., Cheng B., Yu J., Ho W. A review on TiO2-based Z-scheme photocatalysts. Chin. J. Catal. 2017;38:1936–1955. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang S., Zhu B., Liu M., Zhang L., Yu J., Zhou M. Direct Z-scheme ZnO/CdS hierarchical photocatalyst for enhanced photocatalytic H2-production activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019;243:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ali A.M., Emanuelsson E.A.C., Patterson D.A. Photocatalysis with nanostructured zinc oxide thin films: the relationship between morphology and photocatalytic activity under oxygen limited and oxygen rich conditions and evidence for a Mars Van Krevelen mechanism. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010;97:168–181. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pardeshi S.K., Patil A.B. Effect of morphology and crystallite size on solar photocatalytic activity of zinc oxide synthesized by solution free mechanochemical method. J. mol. catal. A-chem. 2009;308:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yogendra K., Naik S., Mahadevan K.M., Madhusudhana N. A comparative study of photocatalytic activities of two different synthesized ZnO composites against Coralene red F3BS dye in presence of natural solar light. J. Environ. Sci. Res. 2011;1:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Georgiev P., Kaneva N., Bojinova A., Papazova K., Mircheva K., Balashev K. Effect of gold nanoparticles on the photocatalytic efficiency of ZnO films. Colloids Surf., A: Phychem. Eng. Asp. 2014;460:240–247. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manikandan A. Vijaya, Judith Narayanan J., Kennedy S., John L. Comparative investigation of structural, optical properties and dye-sensitized solar cell applications of ZnO nanostructures. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014;14:2507–2514. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2014.8499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manikandan A. Vijaya, Judith Ragupathi J., Kennedy C., John L. Optical properties and dye-sensitized solar cell applications of ZnO nanostructures prepared by microwave combustion synthesis. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2014;14:2584–2590. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2014.8515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sumithra V., Manikandan A., Durka M., Jaganathan Saravana Kumar, Dinesh A., Ramalakshmi N., Antony S. Arul. Simple precipitation synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of Mn-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Adv. Sci. Eng. Med. 2017;9:483–488. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poongodi G., Kumar R.M., Jayavel R. Structural, optical and visible light photocatalytic properties of nanocrystalline Nd doped ZnO thin films prepared by spin coating method. Ceram. Int. 2015;41:4169–4175. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2015.03.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdel-wahab M.Sh., Jilani A., Yahia I.S., Al-Ghamdi Attieh A. Enhanced the photocatalytic activity of Ni-doped ZnO thin films: morphological, optical and XPS analysis. Superlattice. Microst. 2016;94:108–118. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qi K., Cheng B., Yu J., Ho W. Review on the improvement of the photocatalytic and antibacterial activities of ZnO. J. Alloy. Comp. 2017;727:792–820. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding Kai, Wang Wei, Wang Wei, Yu Dan, Wang Wei, Gao Pin, Li Baojiang. Facile formation of flexible Ag/AgCl/polydopamine/cotton fabric composite photocatalysts as an efficient visible-light photocatalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018;454:101–111. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu J., Zhu B., You W., Jaroniec M., Yu J. A flexible bioinspired H2-production photocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018;220:148–160. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Mauro Alessandro, Fragalà Maria Elena, Privitera Vittorio, Impellizzeri Giuliana. ZnO for application in photocatalysis: from thin films to nanostructures. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2017;69:44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ben Ameur S., Bel hadjltaief H., Barhoumi A., Duponchel B., Leroy G., Amlouk M., Guermazi H. Physical investigations and photocatalytic activities on ZnO and SnO2 thin films deposited on flexible polymer substrate. Vacuum. 2018;155:546–552. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ben Ameur S., Barhoumi A., Belhadjltaief H., Mimouni R., Duponchel B., Leroy G., Amlouk M., Guermazi H. Physical investigations of undoped and Fluorine doped SnO2 nanofilms on flexible substrate along with wettability and photocatalytic activity tests. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2017;61:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jongnavakit P., Amornpitoksuk P., Suwanboon S., Ndiege N. Preparation and photocatalytic activity of Cu-doped ZnO thin films prepared by the sol-gel method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012;258(20):8192–8198. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu Zhao-Jin, Huang Wei, Cui Ke-Ke, Gao Zhi-Fang, Wang Ping. Sustainable synthesis of metals-doped ZnO nanoparticles from zinc-bearing dust for photodegradation of phenol. J. Hazard Mater. 2014;278:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaneva N.V., Dimitrov D.T., Dushkin C.D. Effect of nickel doping on the photocatalytic activity of ZnO thin films under UV and visible light. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011;257(18):8113–8120. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Y., Lin Y., Wang D., Wang L., Xie T., Jiang T. A high performance cobalt-doped ZnO visible light photocatalyst and its photogenerated charge transfer properties. Nano. Res. 2011;4(11):1144–1152. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu W., Zhang J., Peng T. New insight into the enhanced photocatalytic activity of N-, C- and S-doped ZnO photocatalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2016;181:220–227. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nolan M., Hamilton J., O’Brien S., Bruno G., Pereira L., Fortunato E., Martins R., Povey I., Pemble M. The characterisation of aerosol assisted CVD conducting, photocatalytic indium doped zinc oxide films. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2011;219(1):10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ben Ameur S., Barhoumi A., Mimouni R., Amlouk M., Guermazi H. Low-temperature growth and physical investigations of undoped and (In, Co) doped ZnO thin films sprayed on PEI flexible substrate. Superlattice. Microst. 2015;84:99–112. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boukhachem A., Ouni B., Karyaoui M., Madani A., Chtourou R., Amlouk M. Structural, opto-thermal and electrical properties of ZnO: Mo sprayed thin films. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2012;15:282–292. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bel Hadjltaief H., Ben Ameur S., Da Costa P., Ben Zina M., Gálvez M.E. Photocatalytic decolorization of cationic and anionic dyes over ZnO nanoparticle immobilized on natural Tunisian clay. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018;152:148–157. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bel Hadjltaief H., Ben Zina M., Galvez M.E., Da Costa P. Photocatalytic degradation of methyl green dye in aqueous solution over natural clay-supported ZnO–TiO2 catalysts. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 2016;315:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bechambi O., Chalbi M., Najjar W., Sayadi S. Photocatalytic activity of ZnO doped with Ag on the degradation of endocrine disrupting under UV irradiation and the Investigation of its antibacterial activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015;347:414–420. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramakrishna Reddy K.T., Supriya V., Murata Y., Sugiyama M. Effect of Co-doping on the properties of Zn1-xCoxO films deposited by spray pyrolysis. Surf. Coating. Technol. 2013;231:149–152. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sonia M. Maria Lumina, Anand S., Maria Vinosel V., Asisi Janifer M., Pauline S., Manikandan A. Effect of lattice strain on structure, morphology and magneto-dielectric properties of spinel NiGdxFe2−xO4ferrite nano-crystallites synthesized by sol-gel route. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2018;466:238–251. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asiri S., Guner S., Demir A., Yildiz A., Maznikandan A., Baykal A. Synthesis and magnetic characterization of Cu substituted barium hexaferrites. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2018;28:1065–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yildirim O.A., Arslan H., Sönmezoğlu S. Facile synthesis of cobalt-doped zinc oxide thin films for highly efficient visible light photocatalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016;390:111–121. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bindu P., Thomas Sabu. Estimation of lattice strain in ZnO nanoparticles: X-ray peak profile analysis. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 2014;8:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Singh P., Deepak, Goyal R.N., Pandey A.K., Kaur D. Intrinsic magnetism in Zn1_xCoxO (0.03< x < 0.10) thin films prepared by ultrasonic spray pyrolysis. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 2008;20(1–6):315005. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ilican S., Caglar Y., Caglar M., Demirci B. Polycrystalline indium-doped ZnO thin films: preparation and characterization. J.Opto. Adv. Mater. 2008;10:2592–2598. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gubicza J., Sze´pvolgyi J., Mohai I., Zsoldos L., Unga´r T. Particle size distribution and dislocation density determined by high resolution X-ray diffraction in nanocrystalline silicon nitride powders. Adv. Mater. Res. Switz. 2000;A280:263–269. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Belahssen O., Ben Temam H., Lakel S., Benhaoua B., Benramache S., Gareh S. Effect of optical gap energy on the Urbach energy in the undoped ZnO thin films. Optik. 2015;126:1487–1490. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Janotti A., Van de Walle C.G. Native point defects in ZnO. Phys. Rev. B. 2007;76(16):165–202. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zeng H., Duan G., Li Y., Yang S., Xu X., Cai W. Blue luminescence of ZnO nanoparticles based on non-equilibrium processes: defect origins and emission controls. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2010;20(4):561–572. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liang Z., Xiang Yu, Lei B., Liu P., Mai W. Novel blue–violet photoluminescence from sputtered ZnO thin films. J. Alloy. Comp. 2011;509:5437–5440. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeng H.B., Duan G.T., Li Y., Yang S.K., Xu X.X., Cai W.P. Blue luminescence of ZnO nanoparticles based on non-equilibrium processes: defect origins and emission control. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2010;20:561–572. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heo Y.W., Norton D.P., Pearton S.J. Origin of green luminescence in ZnO thin film grown by molecular-beam epitaxy. J. Appl. Phys. 2005;98(7) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mimouni R., Souissi A., Madouri A., Boubaker K., Amlouk M. High photocatalytic efficiency and stability of chromium-indium codoped ZnO thin films under sunlight irradiation for water purification development purposes. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2017;17(8):1058–1065. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang C.-J. Ce-doped ZnO nanoparticles for efficient photocatalytic degradation of direct red-23 dye. J. Solid State Chem. 2014;214:101–107. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chang Yu-Cheng, Lin Pei-Shih, Liu Fu-Ken, Guo Jin-You, Chen Chien-Ming. One-step and single source synthesis of Cu-doped ZnO nanowires on flexible brass foil for highly efficient field emission and photocatalytic applications. J. Alloys Comp. 2016;688:242–251. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rashid J., Barakat M.A., Salah N., Habib S.S. ZnO-nanoparticles thin films synthesized by RF sputtering for photocatalytic degradation of 2-chlorophenol in synthetic wastewater. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015;23:134–139. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Perillo P.M., Atia M.N. C-doped ZnO nanorods for photocatalytic degradation ofp-aminobenzoic acid under sunlight. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects. 2017;10:125–130. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumar R., Ahmad Umar, Kumar G., Akhtar M.S., Wang Yao, Kim S.H. Ce-doped ZnO nanoparticles for efficient photocatalytic degradation of direct red-23 dye. Ceram. Int. 2015;41:7773–7782. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qiu X., Li L., Zheng J., Liu J., Sun X., Li G. Origin of the enhanced photocatalytic activities of semiconductors: a case study of ZnO doped with Mg2+ J. Phys. Chem. C. 2008;112:12242–12248. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yildirim Ozlem Altintas, Arslan Hanife, Sonmezo˘glu Savas. Facile synthesis of cobalt-doped zinc oxide thin films for highly efficient visible light photocatalysts. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016;390:111–121. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huang M.H., Wu Y., Feick H., Tran N., Weber E., Yang P. Catalytic growth of zinc oxide nanowires by vapor transport. Adv. Mater. 2001;13:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang Q., Zhou W., Shen J., Zhang W., Kong L., Qian Y. A template-free aqueous route to ZnO nanorod arrays with high optical property. Chem. Commun. 2004;21:712–713. doi: 10.1039/b313387g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu L., Hu Y.L., Pelligra C., Chen C.H., Jin L., Huang H., Sithambaram S., Aindow M., Joesten R., Suib S.L. ZnO with different morphologies synthesized by solvothermal methods for enhanced photocatalytic activity. Chem. Mater. 2009;21:2875–2885. [Google Scholar]