Abstract

Purpose

This meta-analysis aimed to estimate the association between gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and occurrence of macrosomia for the first time among Iranian population.

Methods

A systematic review was done of national and international databases. Lists of relevant articles were checked to increase sensitivity of the search reference. Also, access to unpublished articles and documents were accessed by negotiation with related individuals and research centers. These published epidemiological studies (cross-sectional, case-control and cohort studies) were used for comparisons to determine whether GDM was associated with macrosomia. Finally, the Mantel-Haenszel method and the fixed and random-effect models based on heterogeneity of the primary studies were used according to pool results and estimate the odds ratio of macrosomia in women with GDM.

Results

Of 1870 articles, thirty relevant articles were eligible for the current meta-analysis. Our findings showed that 335 of 2524 women with GDM had macrosomia while only 775 of 26,592 women without GDM had macrosomia. Using random-effect model, the pooled odds ratio (OR) relation between GDM and occurrence of macrosomia was estimated as of 5.49 (95% CI: 4.27–7.04). Subgroup analysis showed no difference regarding different study designs and definitions of macrosomia. There was no evidence of publication bias based on the result of Egger’s test (β = 0.1, P = 0.70).

Conclusions

This meta-analysis shows that GDM is directly associated with the risk of macrosomia in the Iranian population. This confirms the findings of previous studies in the wider scientific literature.

Keywords: Gestational diabetes mellitus, Macrosomia, Meta-analysis, Systematic review

Introduction

The prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), defined as variable degree of glucose intolerance with an onset or first recognition during pregnancy, is increasing around the world [1, 2]. Previous studies have documented that infants born of pregnant women with GDM are at risk of several adverse pregnancy outcomes, including macrosomia [3]. Approximately 15–45% of infants born to mothers with GDM may have macrosomia [4]. Macrosomia increases a variety of infant and maternal complications, including higher risk of intrauterine hypoxia, perinatal asphyxia, Erb’s palsy, shoulder dystocia, birth trauma, fetal and neonatal morbidity, maternal hurt in vaginal delivery, and caesarean delivery [5–7]. Although there is different opinions on the definition of macromia, but it is usually defined as infants’ birth weight of more than 4000 g or above the 90th percentile [7, 8]. Iran is a country in which systematic cares has been established for diagnosis and control of GDM. According to the standard protocols of the Iranian ministry of health, all pregnant women are evaluated with oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) by 75 g during 24–28 weeks of pregnancy. These measurements are conducted in primary and secondary health care centers located in all urban and rural areas. In the case of any abnormal test, the pregnant women will be considered as GDM and referred to family physicians for special care and treatment varied from self care training to changing life style and medical treatment which will be continued until three months after delivery [9].

Macrosomia may be caused by different factors such as pregnancy body mass index (BMI), gestational weight gain and placental factors [10]; however, studies have shown a direct correlation between the rate of marosomia and GDM [11, 12]. A meta-analysis study conducted by He et al. [13], recruiting a total of 12 epidemiologic studies (5 cohort studies and 7 case-control studies), has shown that GDM was as an independent risk factor for newborn macrosomia. Another meta-analysis reported that GDM treatment significantly reduced the risk for macrosomia [14]. In addition, GDM treatment was effective in reducing macrosomia, pre-eclampsia and shoulder dystocia [15]. However, some studies have shown that GDM may not be the only cause of macrosomia [16–19]. These discrepancies might be related to the differences between the study populations. Similar findings were seen in women with GDM [20, 21]. On the other hand, a meta-analysis showed that the history of macrosomia was only 10% (95% CI: 6–13) in woman with GDM in Iran [22], which may be due to increasing mean age of the population, urban sedentary lifestyle and the increasing the number of obese women. It has been predicted that GDM will arise as the most important threat in Iran [23–25]. Therefore, it is essential to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis study based on the published observations studies to investigate associated of GDM with macrosomia.

Our comprehensive review showed no systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies about GDM and occurrence of macrosomia in Iran. This meta-analysis was conducted to summarize the results of the available literature in term of epidemiological studies to evaluate the risk of macrosomia for the first time in Iranian women with GDM.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

National and international databanks such as PubMed, Google scholar, Scopus, and Web of science, were searched to find electronically published studies from 2000 to April 25, 2016. The following search strategy and keywords and their Persian equivalents were used; (“GDM” OR “diabetes during pregnancy”) AND (“macrosomia” OR “fetal macrosomia”). The search was carried out from 10 to 23 May 2016. Moreover, the reference lists of the published articles were investigated to increase sensitivity and to identify a higher number of articles. Two researchers, who were working independently, did the search. The concordance coefficient between these two researchers was 81%. Moreover, research centers and subject matter experts involved in this study were sought to seek out related, unpublished studies.

Study selection

Full texts or abstracts of all papers, documents, and reports were extracted during the advanced search. After identification of duplicates, irrelevant studies were removed and the relevant papers were selected by investigating titles, abstracts and full texts of the remaining papers. It is noteworthy that the researchers investigated the results to identify and remove all repeat studies in order to prevent any bias that might have been caused by re-publishing (publication transverse and longitudinal biases).

Quality assessment

After determining the relevant studies in terms of title and content, the STROBE (Elm) checklist was used to assess the quality of the selected studies [26, 27]. The checklist included 12 questions covering various methodological aspects such as sample size of the case and control groups, study design, sampling method, study population, method of data collection, definition of the variables and method of sample examination, tools for data collection, statistical tests, research objectives, appropriate presentation of data and results based on the objectives. Each question was assigned one score and studies with minimum eight scores were included into current meta-analysis.

Inclusion criteria

All English and Persian studies that obtained the least quality assessment score (minimum 8 scores), studies were on human with observational design that were conducted among Iranian women (either cross-sectional, case-control or cohort design), and studies that reported the number of macrosomic neonates among women with and without GDM or studies reported GDM status of mothers delivered macrosome or normal babies were included into the current meta-analysis.

Exclusion criteria

All case reports, case series, animal experiments, in vitro studies, studies that did not sufficient required information, congress abstracts without full texts, studies that did not achieve the minimum quality assessment scores, and studies that did not specify the temporal priority of exposure (GDM) over the outcome (macrosomia) which is one of the principles of Hill’s causal relations were excluded from the meta-analysis.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using a standard abstraction sheet forms in excel software version 2007 according to title, first name of author, year of study, type of study, effect of GDM on macrosomia, definition of macrosomia, sample size in each group, number of infants that were born with the condition of macrosomia according to GDM status and publication language.

Analysis

The Stata version 11 software was used for data analysis. The heterogeneity index between the studies was determined using the Cochran’s test (Q) and I-square index. The random-effect models with the Mantel–Haenszel method were used to estimate the pooled odds ratio for macrosomia. The 95% CI were illustrated in forest plots. In these curves, the box size and the lines on both sides represent the weight of each study and the 95% CI, respectively. Moreover, the egger test was used to assess publication bias with the significance levels less than 0.1. Also, the meta-regression and subgroup analysis were conducted in terms of the study design (cross-sectional, case-control and cohort) and definition of macrosomia (birth weight > 4 kg compared to birth weight > 4.5 kg), to assess risk factors for heterogeneity.

Results

1870 articles were found during the primary search. After restricting the search strategy and removing all duplicates, 560 documents remained. A review of titles and abstracts determined 491 studies as irrelevant. The full texts of the 69 remaining articles were investigated and 45 cases were identified as irrelevant. After investigating the references, 10 relevant articles were also found. Applying the inclusion/exclusion criteria and quality assessment, 4 documents were omitted and finally, 30 articles were determined eligible for final meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Literature search and review flowchart for selection of primary studies

Reports of the relationship between the previous macrosomia and GDM were evident in 21 articles [21, 24, 28–48], while nine articles [21, 24, 49–55] assessed the relationship between macrosomia and GDM during pregnancies. Published articles from 2002 to 2015 were entered into the meta-analysis. These studies included eight cohorts, four case-controls and 18 cross-sectional studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of primary studies included to a meta-analysis

| Reference no. | Publication year | Type of study | Definition Of Macrosomia (birth weight) |

With GDM | Without GDM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Macrosomia | Without Macrosomia | With Macrosomia | Without Macrosomia | ||||

| Garshasbi et al., [28] | 2008 | C-S | >4000 g | 16 | 108 | 81 | 1723 |

| Goli et al. [29] | 2012 | C-S | NR | 1 | 76 | 2 | 1935 |

| Hoseini et al. [30] | 2011 | C-S | >4500 g | 40 | 74 | 6 | 107 |

| Mohamad-beigi et al. [31] | 2007 | C-C | NR | 2 | 46 | 10 | 340 |

| Mirfazi et al. [32] | 2010 | C-S | >4000 g | 11 | 113 | 5 | 539 |

| Atashzadeh et al. [33] | 2006 | C-S | >4500 g | 3 | 104 | 20 | 2094 |

| Zokaie et al. [34] | 2014 | C-C | >4000 g | 26 | 194 | 4 | 216 |

| Hossein-nezhad et al. [35] | 2009 | Cohort | >4000 g | 29 | 85 | 99 | 2203 |

| Rahimi et al. [36] | 2010 | C-S | >4000 g | 3 | 56 | 11 | 1650 |

| Dehaki et al. [37] | 2015 | C-S | >4000 g | 1 | 16 | 4 | 342 |

| Fekrat et al. [38] | 2004 | C-S | >4000 g | 13 | 49 | 7 | 73 |

| Shahbaziyan et al. [39] | 2012 | C-S | >4000 g | 3 | 47 | 3 | 646 |

| Mohamad-beigi et al. [40] | 2009 | C-S | >4000 g | 8 | 62 | 10 | 340 |

| Navaei et al. [41] | 2002 | C-S | >4000 g | 3 | 16 | 45 | 669 |

| Mohamadzadeh et al. [42] | 2012 | C-S | >4000 g | 6 | 56 | 11 | 1203 |

| Bozari et al. [43] | 2013 | C-S | >4000 g | 7 | 78 | 5 | 914 |

| Sohalizadeh et al. [44] | 2014 | C-C | >4000 g | 2 | 110 | 1 | 111 |

| Khooshideh et al. [45] | 2008 | Cohort | >4000 g | 5 | 62 | 6 | 327 |

| Maghboli et al. [46] | 2005 | Cohort | >4000 g | 29 | 85 | 99 | 2203 |

| Hadaegh et al. [47] | 2005 | C-S | >4000 g | 3 | 59 | 5 | 633 |

| Soheilykhah et al. [48] | 2010 | Cohort | >4000 g | 6 | 104 | 8 | 876 |

| Keshavarz et al. [24] | 2005 | Cohort | >4000 g | 5 | 58 | 35 | 1212 |

| Hossein-Nezhad et al. [21] | 2007 | C-S | >4000 g | 18 | 96 | 168 | 1694 |

| Larijani et al. [49] | 2004 | C-S | >4000 g | 29 | 85 | 78 | 2224 |

| Karimi et al. [50] | 2002 | Cohort | >4000 g | 10 | 54 | 22 | 824 |

| Akhlaghi et al. [51] | 2012 | C-S | >4000 g | 2 | 30 | 1 | 31 |

| Mohamad-beigi et al. [52] | 2008 | Cohort | >4000 g | 17 | 53 | 15 | 335 |

| Sharifi et al. [53] | 2010 | C-C | >4000 g | 14 | 52 | 1 | 65 |

| Eslamian et al. [54] | 2013 | Cohort | >4000 g | 19 | 93 | 12 | 147 |

| Karajibani et al. [55] | 2015 | C-S | >4000 g | 4 | 68 | 1 | 141 |

Data presented as number

C-S: cross-sectional, C-C: case control, NR: not reported

The results of 21 studies determined that from a total of 1817 women with GDM, 217 had reported macrosomia during previous pregnancies. Among 19,586 women without GDM, 442 babies with macrosomia had been born in previous pregnancies. The pooled estimate of the odds of macrosomia in the GDM group was six times higher than that in the healthy group (OR = 6.01, 95% CI: 4.70–7.68). In addition, heterogeneity indices showed no significant heterogeneity between results (Q = 24.7, I-squared = 19.2%, P = 0.20). Therefore, the fixed-effect model was applied to pool the primary results (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Estimation of Odds Ratio (OR) between gestational diabetes mellitus and macrosomia (based on studies that were examined the association GDM with history of occurrence macrosomia in pervious pregnancy and GDM with occurrence of macrosomia in current pregnancy)

Results of nine studies showed; out of 707 women with GDM and 7006 women without GDM, 118 and 333 macrosomic babies were born respectively during current pregnancies. Using the random effect model (Q = 28.6, I-squared = 72, P < 0.001), the pooled odds ratio for GDM was estimated as of 4.74 (95% CI: 2.69–8.36) (Fig. 2).

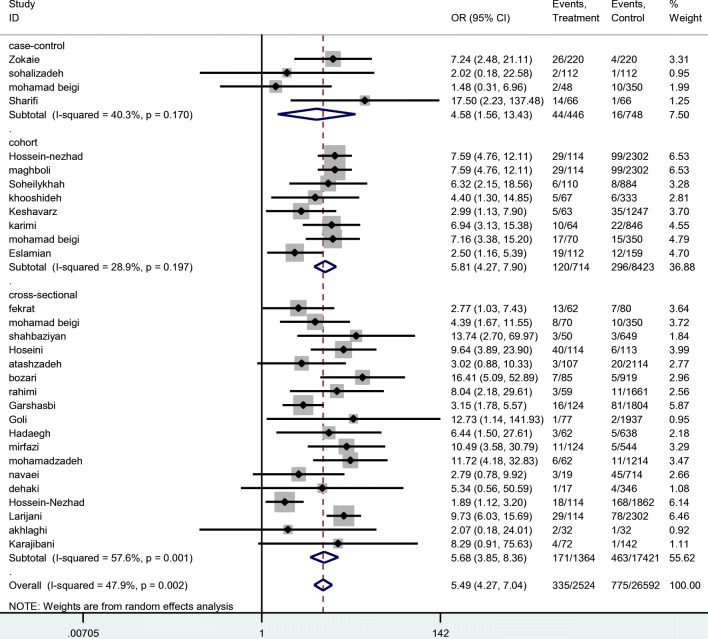

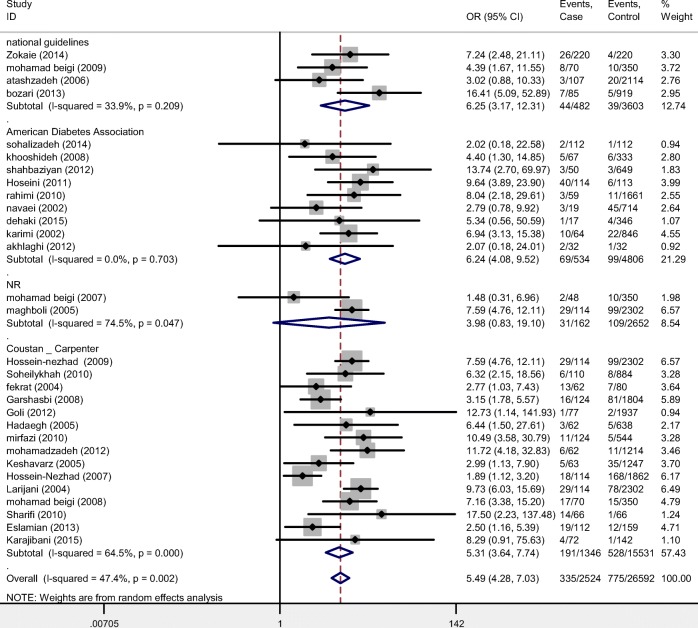

Considering the results of all 30 studies, total frequencies of macrosomic newborns in women with and without GDM were estimated as of 335/2524 and 775/26592 respectively indicating a pooled odds ratio as of 5.49 (95% CI: 4.27–7.04) (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3.

Estimation of Odds Ratio (OR) between gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and macrosomia by total and type of study

Fig. 4.

Estimation of Odds Ratio (OR) between gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and macrosomia by subgroup analysis (diagnosis criteria)

Stratified analysis showed no difference regarding different study designs and definitions of macrosomia. There was no indication of publication bias from the result of Egger’s test (β = 0.1, P = 0.70) (Fig. 4).

Results of the Egger’s test showed no publication bias in the results (β = 0.1, P = 0.70). Heterogeneity tests of the results (Q = 55.7, I-squared = 47.9%, P = 0.002) showed that there is heterogeneity across included primary studies in current meta-analysis. Factors of type of study and definition of macrosomia were examined using the Meta regression model that the results were showed type of study and definition of macrosomia did not have a no significant role in heterogeneity (β = 0.8, p = 0.40) and (β = 0.1, P = 0.20), respectively.

Discussion

For Iranian women with GDM there is a scarcity of literature regarding their risk for infant macrosomia. Thus, we performed this first meta-analysis of observational studies in Iranian population. The present study revealed that in this population the odds of macrosomia were strongly associated with GDM; i.e. macrosomia was 5.49 fold higher in women with GDM in compared with those without GDM. This systematic review showed that women with GDM have a higher risk of producing offspring with macrosomia. Therefore, evaluating women with GDM can facilitate more targeted screening as a measure for macrosomia and can help improve primary health care. On the other hand, some of primary studies included into our meta-analysis reported the high prevalence of fetal macrosomia in previous pregnancies. In this line, in a meta-analysis, history of macrosomia was considered as one of common risk factor for GDM [22]. To reduce the risk of macrosomia, blood glucose concentrations should be monitored during pregnancy. Recent studies showed that diet or exercise can be used to decrease GDM-related adverse outcomes. Barakat et al. [56] demonstrated a 58% reduction in GDM-related risk of having a newborn with macrosomia by exercise compared to the control group. Asemi et al. [57] indicated that the adherence to dietary approaches to stop hypertension diet for 4 weeks in women with GDM led to lower rates of macrosomic babies. In a meta-analysis including ten primary studies, GDM treatment any form of treatment ranging from dietary intervention to drug therapy, including insulin and anti-diabetic agents significantly reduced the risk for macrosomia [14]. Furthermore, previous systematic review studies have demonstrated that GDM treatment is effective in reducing macrosomia, pre-eclampsia and shoulder dystocia [15, 58].

GDM is characterized by an elevated placental transport of glucose from the mother to the fetus, resulting in macrosomia [59]. Convincing studies have demonstrated that GDM is associated with macrosomia [60, 61]. Hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance in women with GDM result in fetal hyperglycaemia and hyperinsulinemia, leading to hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the Langerhans’ islets and, consequently, increased growth of fetal tissues and organs [62]. Whereas placenta does not allow transfer of fetal insulin to mother, a large quantity of mother’s glucose is metabolized in the fetus resulting in increased lipogenesis and excessive growth of the fetus [62]. In a study conducted by Eslamian et al. [63], macrosomal newborns from GDM women had significantly higher insulin concentrations in cord blood than normal weight and small babies, which confirms the importance of insulin as the most important tissue growth hormone. Supporting our study, Alberico et al. [64] showed that GDM was an independent risk factor predictor for macrosomia; even after adjustment for gestational age at birth, mother’s height, infant sex, and parity. A comparison of reported previous reviews with our review in different settings indicted that OR macrosomia in Iranian women with GDM was higher than previous reviews in higher income countries (5.49 vs. 1.71) [65]. The different findings might be explained by different confounding variables as well as different participants of the study [66, 67]. Another reason for this variation may be because analyses of associations between GDM to macrosomia had overlooked adjustment for some confounding factors in recent meta-analysis. Similarly, previous studies have suggested that GDM was most commonly associated with macrosomia [7, 18, 60, 61, 65, 68]. In support of the above, some studies have proven that neonates with macrosomia have a significant insulin levels in the cord blood supply, which effects insulin hormone in such a way that causes overgrowth of the fetus [54, 69]. Therefore, our meta-analysis provided reliable evidence in favor of a direct association between GDM and macrosomia. Previous studies have reported that the risk of developing macrosomia may be reduced by consideration of some criteria for GDM management such as the detection, diagnosing and treating pregnant women with GDM based on a uniform approach and standard screening protocol. Also, we should think on medication and non-medication interventions [56, 57, 70, 71].

Our study was conducted by a comprehensive search of published articles without any language restrictions and included all studies in Iran. Our meta-analysis used of ‘OR’ for estimates of clinical quantity for use in screening woman with GDM for macrosomia. The study included entries of various populations from all over Iran, and methods of determining the consequence. Meta regression analysis was applied according to study method to recognize heterogeneity and results showed no significant difference. One limitation of this study was that the point odds ratios reported by the primary studies were estimated without adjustment for some confounding factors such as obesity and gestational weight gain because of conditions of some primary studies. In addition, most of the primary studies did not report the influence of GDM treatment on the outcomes of pregnancy such as macrosomia, and we had to combine all results without considering such confounding factor. Beside these weaknesses, results of this meta-analysis provide valuables implications for preventive strategies in the communities. According to the adverse outcomes of macrosomia for mothers and babies, all pregnant women should be evaluated during pregnancy from the viewpoint of gestational diabetes. These results show that any women diagnosing with GDM should be managed more seriously than before and prenatal cares should be prepared for such mothers and newborns.

Conclusion

This first meta-analysis from Iran indicates that GDM is strongly associated with an increased risk of macrosomia in Iranian women. According to our findings, interventions to control GDM should be taken into account among health providers to prevent macrosomia in women with GDM.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the Torbat Heydariyeh University of Medical Sciences, Torbat Heydariyeh, Iran under Grant number A-10-1304-5.

Abbreviations

- GDM

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

Authors’ contribution

RT, ZA, KL, MA, SK, MA, MK, and MM contributed in conception, design, statistical analyses, data interpretation and manuscript drafting. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

None of the authors had any personal or financial conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Reza Tabrizi, Email: kmsrc89@gmail.com.

Zatollah Asemi, Email: asemi_r@yahoo.com.

Kamran B. Lankarani, Email: kblankarani@gmail.com

Maryam Akbari, Email: m.akbari45@yahoo.com.

Seyed Reza Khatibi, Email: Khatibiser@gmail.com.

Ahmad Naghibzadeh-Tahami, Email: anaghibzadeh61@gmail.com.

Mojgan Sanjari, Email: mjnsanjari@gmail.com.

Hosniyeh Alizadeh, Email: a.naghibzadeh@kmu.ac.ir.

Mahdi Afshari, Email: Mahdiafshari99@gmail.com.

Mahmoud Khodadost, Email: mahmodkhodadost@yahoo.com.

Mahmood Moosazadeh, Phone: +98-9113555367, Email: mmoosazadeh1351@gmail.com.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association Gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl. 1):88–90. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Diabetes Association Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Supplement 1):S62–SS9. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben-Ziv RG, Hod M. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Fetal Matern Med Rev. 2008;19(03):245–269. doi: 10.1017/S0965539508002234. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kc K, Shakya S, Zhang H. Gestational diabetes mellitus and macrosomia: a literature review. Ann Nutr Metab. 2015;66(Suppl 2):14–20. doi: 10.1159/000371628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jensen DM, Damm P, Sørensen B, Mølsted-Pedersen L, Westergaard J, Korsholm L, et al. Proposed diagnostic thresholds for gestational diabetes mellitus according to a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test. Maternal and perinatal outcomes in 3260 Danish women. Diabet Med. 2003;20(1):51–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mondestin MA, Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. Birth weight and fetal death in the United States: the effect of maternal diabetes during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187(4):922–926. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.127458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rossi AC, Mullin P, Prefumo F. Prevention, management, and outcomes of macrosomia: a systematic review of literature and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2013;68(10):702–709. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000435370.74455.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suhonen L, Hiilesmaa V, Kaaja R, Teramo K. Detection of pregnancies with high risk of fetal macrosomia among women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87(9):940–945. doi: 10.1080/00016340802334377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Center for Disease Control. Essential interventions for non-communicable diseases in primary health care system (IRAPEN). Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education. 2017:27–9.

- 10.Lepercq J, Timsit J, Hauguel-de MS. Etiopathogeny of fetal macrosomia. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod. 2000;29(1 Suppl):6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Combs CA, Gunderson E, Kitzmiller JL, Gavin LA, Main EK. Relationship of fetal macrosomia to maternal postprandial glucose control during pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 1992;15(10):1251–1257. doi: 10.2337/diacare.15.10.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Durnwald CP, Mele L, Spong CY, Ramin SM, Varner MW, Rouse DJ, et al. Glycemic characteristics and neonatal outcomes of women treated for mild gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(4):819–827. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820fc6cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He XJ, Qin FY, Hu CL, Zhu M, Tian CQ, Li L. Is gestational diabetes mellitus an independent risk factor for macrosomia: a meta-analysis? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(4):729–735. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3545-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poolsup N, Suksomboon N, Amin M. Effect of treatment of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e92485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falavigna M, Schmidt MI, Trujillo J, Alves LF, Wendland ER, Torloni MR, et al. Effectiveness of gestational diabetes treatment: a systematic review with quality of evidence assessment. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;98(3):396–405. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esakoff TF, Cheng YW, Sparks TN, Caughey AB. The association between birthweight 4000 g or greater and perinatal outcomes in patients with and without gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(6):672 e1–672 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falavigna M, Prestes I, Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Colagiuri S, Roglic G. Impact of gestational diabetes mellitus screening strategies on perinatal outcomes: a simulation study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99(3):358–365. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shelley-Jones DC, Beischer NA, Sheedy MT, Walstab JE. Excessive birth weight and maternal glucose tolerance--a 19-year review. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1992;32(4):318–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.1992.tb02842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moosazadeh M, Asemi Z, Lankarani KB, Tabrizi R, Maharlouei N, Naghibzadeh-Tahami A, et al. Family history of diabetes and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Research & Reviews: Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome; 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamali S, Shahnam F, Pour-Memari MH. Gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed with a 2-h 75-gram oral glucose tolerance test and adverse pregnancy outcomes. J Zanjan Univ Med Sci. 2003;11(43):17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hossein-Nezhad A, Maghbooli Z, Vassigh AR, Larijani B. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus and pregnancy outcomes in Iranian women. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;46(3):236–241. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(08)60026-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiani F, Naz MSG, Sayehmiri F, Sayehmiri K, Zali H. The risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and Meta-analysis study. Int J Womens Health Reprod Sci. 2017;10(4):253–263. doi: 10.15296/ijwhr.2017.44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flores-Le Roux JA, Chillaron JJ, Goday A, Puig De Dou J, Paya A, Lopez-Vilchez MA, et al. Peripartum metabolic control in gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2010;202(6):568 e1–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Keshavarz M, Cheung NW, Babaee GR, Moghadam HK, Ajami ME, Shariati M. Gestational diabetes in Iran: incidence, risk factors and pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;69(3):279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Z, Kanguru L, Hussein J, Fitzmaurice A, Ritchie K. Incidence of adverse outcomes associated with gestational diabetes mellitus in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;121(1):14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akbari M, Lankarani KB, Honarvar B, Tabrizi R, Mirhadi H, Moosazadeh M. Prevalence of malocclusion among Iranian children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2016;13(5):387. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.192269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akbari M, Moosazadeh M, Ghahramani S, Tabrizi R, Kolahdooz F, Asemi Z, Lankarani KB. High prevalence of hypertension among Iranian children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2017;35(6):1155–1163. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garshasbi A, Faghihzadeh S, Naghizadeh MM, Ghavam M. Prevalence and risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus in Tehran. J Family Reprod Health. 2008;2(2):75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goli M, Hemmat AR, Foroughipour A. Risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus in Iranian pregnant women. J Health Syst Res. 2012;8(2):282–289. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoseini SS, Hantoushzadeh S, Shoar S. Evaluating the extent of pregravid risk factors of gestational diabetes mellitus in women in Tehran. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2011;13(6):407. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohammad Beigi A, Tabatabaei H, Zeighami B, Mohammad SN. Determination of diabetes risk factors during pregnancy among women reside in Shiraz. Iran J Diabetes Lipid Disord. 2007;7(1):77–84. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mirfazi M, Azariyan A, Mirheidary M. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and its' risk factors among pregnant women in Karaj, 2008. Iran J Diabetes Lipid Disord. 2010;9(4):376–382. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atashzadeh SF. Frequency of gestational diabetes and its related factors in pregnant women in prenatal clinics of educational hospitals, in Tehran (Oct 2000-March 2002) J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci. 2006;5(3):175–180. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zokaie M, Majlesi F, Rahimi-Foroushani A, Esmail-Nasab N. Risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus in Sanandaj, Iran. Chron Dis J. 2014;2(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hossein-Nezhad A, Maghbooli Z, Larijani B. Maternal glycemic status in GDM patients after delivery. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2009;8:12. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rahimi M, Dinari Z, Najafi F. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and the relative risk factors in pregnant women in Kermanshah, 2008. Behbood J. 2010;4(3):244–50 [Persian].

- 37.Mohammadpour-Dehaki R, Shahdadi H, Shamsizadeh M, Forghani F. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and risk factors in pregnant women referring to health center in Zabol City. J Rostamineh Zabol Univ Med Sci. 2015;7(3):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fekrat M, Kashanian M, Jahanpour J. Risk factors in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Iran Univ Med Sci. 2004;11(43):815–820. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shahbazian HB, Shahbazian Nahid, Yarahmadi Mehdi, Saiedi Saied. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in pregnant women referring to gynecology and obstetrics clinics. 2012.

- 40.Mohamadbeigi A, Tabatabaee H, Mohamadsalehi N. Modeling the determinants of gestational diabetes in Shiraz. Kashan Univ Med Sci J (Feyz) 2009;13(1):37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Navaei L, Kimyagar M, Khirkhahi M, Azizi F. An epidemiological study of diabetes among pregnant women in Tehran villages. J Shahid Beheshti Univ Med Sci. 2002;26(3):217–223. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mohamadzadeh F, Mobasheri A, Eshghiniya S, Kazeminezhad V, Vakili M. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and its' risk factors among pregnant women in Gorgan City Between 2011 to 2012. Iran J Diabetes Lipid Disord. 2012;12(3):204–210. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bozari Z, Yazdani S, Abedi Samakosh M, Mohammadnetaj M, Emamimeybodi S. Prevalence of gestational diabetes and its risk factors in pregnant women referred to health centers of Babol, Iran, from September 2010 to March 2012. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2013;16(43):6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soheylizad M, Khazaei S, Mirmoeini RS, Gholamaliee B. Determination of risk factors for gestational diabetes mellitus in the rural population of Hamadan Province in 2011: a case-control study. Pajouhan Sci J. 2014;13(1):9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khooshideh M, Shahriari A. Comparison of universal and risk factor based screening strategies for gestational diabetes mellitus. Shiraz E Med J. 2008;9(1):24–29. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maghbooli Z, Hossein-Nezhad A, Larijani B. Predictive factors of diabetes after pregnancy in women with gestational diabetes history. Iran J Diabetes Lipid Disord. 2005;4(4):27–36. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hadaegh F, Tohidi M, Harati H, Kheirandish M, Rahimi S. Prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in southern Iran (Bandar Abbas City) Endocr Pract. 2005;11:313–318. doi: 10.4158/EP.11.5.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soheilykhah S, Mogibian M, Rahimi-Saghand S, Rashidi M, Soheilykhah S, Piroz M. Incidence of gestational diabetes mellitus in pregnant women. Iran J Reprod Med. 2010;8(1):24–28 [Persian].

- 49.Larijani B, Hossein-Nezhad A, Vassigh A-R. Effect of varying threshold and selective versus universal strategies on the cost in gestational diabetes mellitus. Arch Iran Med. 2004;7(4):267–271. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karimi F, Nabipoor I, Jafari M, Gholamzadeh F. The selective screening of gestational diabetes based on 50-gram glucose in pregnant women in Bushehr. Iran J Diabetes Lipid Disord. 2002;2(1):51–45. [Persian].

- 51.Akhlaghi F, Bagheri SM, Rajabi O. A comparative study of relationship between micronutrients and gestational diabetes. ISRN Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:470419. doi: 10.5402/2012/470419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mohammadbeigi A, Tabatabaee Seyed H, Mohammadsalehi N, Yazdani M. Gestational diabetes and its association with unpleasant outcomes of pregnancy. Pak J Med Sci. 2008;24(4):566–570. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharifi F, Ziaee A, Feizi A, Mousavinasab N, Anjomshoaa A, Mokhtari P. Serum ferritin concentration in gestational diabetes mellitus and risk of subsequent development of early postpartum diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2010;3:413–419. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S15049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eslamian L, Akbari S, Marsoosi V, Jamal A. Effect of different maternal metabolic characteristics on fetal growth in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Iran J Reprod Med. 2013;11(4):325. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karajibani M, Montazerifar F. The relationship between some risk factors and gestational diabetes mellitus in pregnant women referred to health and treatment centers in Zahedan, Iran, in 2012. Iran J Health Sci. 2015;3(1):44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barakat R, Pelaez M, Lopez C, Lucia A, Ruiz JR. Exercise during pregnancy and gestational diabetes-related adverse effects: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47(10):630–636. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Asemi Z, Samimi M, Tabassi Z, Esmaillzadeh A. The effect of DASH diet on pregnancy outcomes in gestational diabetes: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2014;68(4):490–495. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2013.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hartling L, Dryden DM, Guthrie A, Muise M, Vandermeer B, Donovan L. Benefits and harms of treating gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. preventive services task force and the National Institutes of Health Office of medical applications of research. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(2):123–129. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-2-201307160-00661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Assche FA, Holemans K, Aerts L. Long-term consequences for offspring of diabetes during pregnancy. Br Med Bull. 2001;60:173–182. doi: 10.1093/bmb/60.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ategbo JM, Grissa O, Yessoufou A, Hichami A, Dramane KL, Moutairou K, et al. Modulation of adipokines and cytokines in gestational diabetes and macrosomia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(10):4137–4143. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grissa O, Ategbo JM, Yessoufou A, Tabka Z, Miled A, Jerbi M, et al. Antioxidant status and circulating lipids are altered in human gestational diabetes and macrosomia. Transl Res. 2007;150(3):164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Di Cianni G, Miccoli R, Volpe L, Lencioni C, Del Prato S. Intermediate metabolism in normal pregnancy and in gestational diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2003;19(4):259–270. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eslamian L, Akbari S, Marsoosi V, Jamal A. Effect of different maternal metabolic characteristics on fetal growth in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Iran J Reprod Med. 2013;11(4):325–334. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alberico S, Montico M, Barresi V, Monasta L, Businelli C, Soini V, et al. The role of gestational diabetes, pre-pregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain on the risk of newborn macrosomia: results from a prospective multicentre study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2014;14(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.He X-J, F-y Q, Hu C-L, Zhu M, Tian C-Q, Li L. Is gestational diabetes mellitus an independent risk factor for macrosomia: a meta-analysis? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2015;291(4):729–735. doi: 10.1007/s00404-014-3545-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang Z, Kanguru L, Hussein J, Fitzmaurice A, Ritchie K. Incidence of adverse outcomes associated with gestational diabetes mellitus in low-and middle-income countries. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2013;121(1):14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fadl HE, Östlund I, Magnuson A, Hanson US. Maternal and neonatal outcomes and time trends of gestational diabetes mellitus in Sweden from 1991 to 2003. Diabet Med. 2010;27(4):436–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.02978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mitanchez D. Fetal and neonatal complications of gestational diabetes: perinatal mortality, congenital malformations, macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, birth injuries, neonatal outcomes. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Biol. Reprod. 2010;39(8 Suppl 2):S189–S199. doi: 10.1016/S0368-2315(10)70046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ragnarsdottir LH, Conroy S. Development of macrosomia resulting from gestational diabetes mellitus: physiology and social determinants of health. Advances in Neonatal Care. 2010;10(1):7–12. doi: 10.1097/ANC.0b013e3181bc8559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Metzger BE, Coustan DR, Committee O. Summary and recommendations of the fourth international workshop-conference on gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:B161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Group NDD Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 1979;28(12):1039–1057. doi: 10.2337/diab.28.12.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]