Abstract

Hazelnut is one of the most frequent causes of food allergy. The major hazel allergen in Northern Europe is Cor a 1, which is homologous to the major birch pollen allergen Bet v 1. Both allergens belong to the pathogenesis related class PR-10. We determined the solution structure of Cor a 1.0401 from hazelnut and identified a natural ligand of the protein. The structure reveals the protein fold characteristic for PR-10 family members, which consists of a seven-stranded antiparallel β-sheet, two short α-helices arranged in V-shape and a long C-terminal α-helix encompassing a hydrophobic pocket. However, despite the structural similarities between Cor a 1 and Bet v 1, they bind different ligands. We have shown previously that Bet v 1 binds to quercetin-3-O-sophoroside. Here, we isolated Cor a 1 from hazel pollen and identified the bound ligand, quercetin-3-O-(2“-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl)-β-D-galactopyranoside, by mass spectrometry and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR). NMR experiments were performed to confirm binding. Remarkably, although it has been shown that PR-10 allergens show promiscuous binding behaviour in vitro, we can demonstrate that Cor a 1.0401 and Bet v 1.0101 exhibit highly selective binding for their specific ligand but not for the respective ligand of the other allergen.

Subject terms: Solution-state NMR, Plant molecular biology

Introduction

Allergy to hazel is very common in Europe1,2 and has even been found to be the most frequent cause of IgE-mediated food allergy3–5. Cor a 1.04, a Bet v 1 homologous allergen, which belongs to the family of pathogenesis-related plant proteins PR-106,7 is the major hazelnut allergen in Northern Europe8. About 53% of people allergic to birch pollen suffer from cross reactivity to Cor a 1.049.

PR-10 proteins are part of the plants’ immune defence and are mostly induced by attack of different pathogens10,11 or abiotic stress stimuli12,13. However, in certain plant tissues that have higher risks of being attacked by insects, fungi or of being damaged by UV-radiation, PR-10 proteins are expressed constitutively14. They are encoded by multiple genes and therefore occur as a mixture of different isoallergens with >67% sequence identity and variants (formerly also called isoforms) thereof, which share a very high sequence identity of >90%15.

The molecular role of PR-10 proteins under physiological conditions in different plants remains elusive. Numerous studies on recombinant ligand-free Bet v 1 exist, which show that it binds to a multitude of different ligands in vitro like flavonoids, cytokines and fatty acids with dissociation constants in the micromolar range16–20.

Different Cor a 1 isoallergens and variants have been identified in hazel pollen as well as in hazelnut and hazel leaves21. In hazel pollen four different variants of Cor a 1.01, termed Cor a 1.0101 to Cor a 1.0104, have been detected22. Cor a 1.02 and Cor a 1.03 isoallergens can be found in mature hazel leaves23. In hazelnut, four different variants of Cor a 1.04, Cor a 1.0401 to Cor a 1.0404 have been identified7. Interestingly, Cor a 1.04 variants show a higher sequence identity to Bet v 1.0101 (66–67%) than to Cor a 1.01 variants from hazel pollen (61–65%)7.

Although Bet v 1 has been extensively studied biochemically16,24–27 as well as immunologically25,28–31, the exact physiological role of this protein and its homologs derived from different plants remains elusive.

Typically, the structure of PR-10 proteins consists of a seven-stranded, antiparallel β-sheet and a long, C-terminal α-helix which is enclosed by two shorter helices arranged in V-shape. Those elements encompass a large hydrophobic pocket32. Their common structure indicates a more general function, e.g. as storage- or transport-proteins.

To shed light on the physiological role of those proteins, we previously identified the glycosylated flavonoid quercetin-3-O-sophoroside (Q3OS) as a natural ligand of Bet v 1.0101 by co-purification of the protein-ligand-complex from birch pollen33. Moreover, we found that different Bet v 1.01 variants show different binding behaviour34 and that the binding specificity is driven by the sugar moiety of the ligand33.

To investigate whether PR-10 proteins from other plants have identical or similar ligands and ligand binding behaviour, we purified Cor a 1 from hazel pollen in the presence of its ligand. We were able to identify quercetin-3-O-(2″-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl)-β-D-galactopyranoside (Q3O-(Glc)-Gal) as a natural ligand. Compared to Q3OS the only difference between the two ligands is the orientation of the C4 OH group in the first sugar moiety.

Most surprisingly, we can demonstrate that although they are known to show promiscuous ligand binding behaviour, the PR-10 allergens Bet v 1.0101 and Cor a 1.0401 exhibit strong binding specificities only for their own, almost identical ligands. Structure determination of Cor a 1.0401 and binding studies with quercetin, as well as with the ligands Q3OS and Q3O-(Glc)-Gal were performed to analyse the binding specificities.

Results and Discussion

Solution structure of Cor a 1.0401

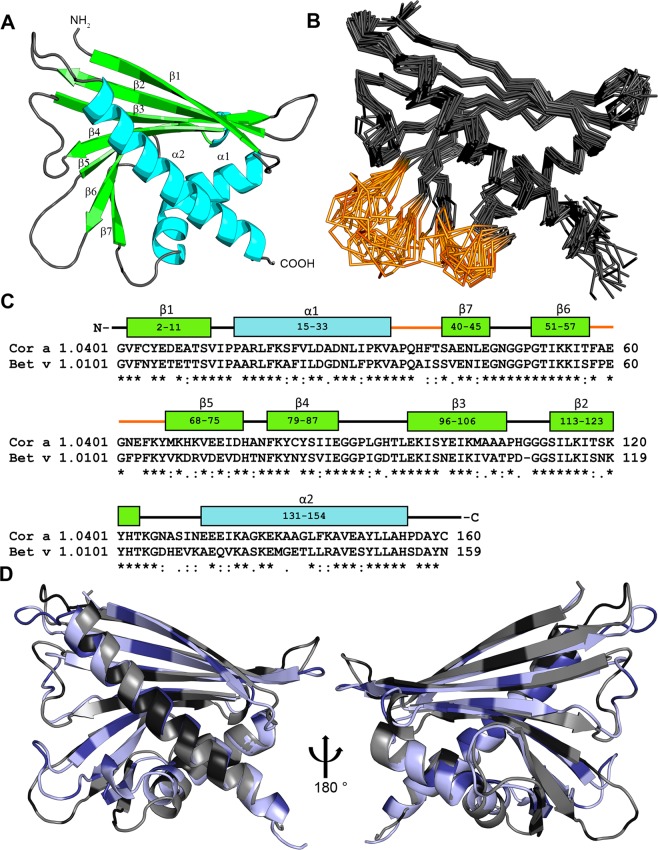

To determine the solution structure of Cor a 1 we used a tagless, 160 amino acids long full length construct of the recombinant variant Cor a 1.0401, expressed in Escherichia coli (E. coli) and performed multidimensional heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy analyses. The spectra exhibited the large dispersion of chemical shifts typical for a well folded globular protein. The structure of Cor a 1.0401 showed the overall fold typical for PR-10 allergens, consisting of a seven-stranded antiparallel β-sheet followed by a long C-terminal helix, which is enclosed by two shorter helices arranged in V-shape that comprise a hydrophobic pocket (Fig. 1A; Table 1). No resonances could be identified in the NMR spectra for residues in the regions Ala35 - Thr40 (between strand β7 and the two short α-helices) and Thr58 - Met68 (between strand β5 and β6) (Fig. 1B,C). These regions consist of loops which, similarly to the strawberry allergen Fra a 1 probably show dynamic behaviour on unfavorable timescales to broaden NMR signals beyond detection35. As a consequence of missing signals and corresponding lack of structural restraints a structural definition in this regions was not possible, and these loops differ significantly in the calculated structural ensemble (Fig. 1B). We solved the NMR solution structure of the homologous PR-10 allergen Bet v 1.0101 (PDB: 6R3C; see Supplementary Fig. S1, Table S1) in order to compare the two solution structures (Fig. 1D). The overlay of the Cor a 1.0401 solution structure and the high resolution structure of Bet v 1.0101 reveals the high structural similarity of the two proteins. Despite of the lower number of identified restraints for Cor a 1.0401, the overlay indicates that the structure is sufficiently good to show the overall fold of the protein and to identify its hydrophobic cavity, which is important for ligand binding.

Figure 1.

Solution structure of Cor a 1.0401. (A) Cartoon representation of the average of the 20 lowest energy solution structures of Cor a 1.0401 (PDB: 6GQ9) (α-helices, turquoise; β-strands, green; loop-regions, grey). (B) Backbone overlay of the 20 lowest energy solution structures of Cor a 1.0401, with a backbone rmsd value of 0.93 Å and overall rmsd of 1.26 Å. The loop regions Ala35 - Thr40 (between strand β7 and the two short α-helices) and Thr58 - Met68 (between strand β5 and β6) which did not show resonances are highlighted in brown. (C) Amino acid sequence alignment of Cor a 1.0401 and Bet v 1.0101. The α-helices and β strands of Cor a 1.0401 are shown in blue and green, respectively, the two loop regions are highlighted in brown. (D) Overlay of the structures of Cor a 1.0401 (grey) and Bet v 1.0101 (light blue) (PDB: 6R3C). Black and dark blue indicate sequence differences.

Table 1.

Solution structure statistics of Cor a 1.0401.

| Experimentally derived restraints | ||

|---|---|---|

| distance restraints | ||

| NOE | 845 | |

| intraresidual | 1 | |

| sequential | 240 | |

| medium range | 176 | |

| long range | 428 | |

| hydrogen bonds | 80 | |

| dihedral restraints | 208 | |

| restraint violation | ||

| average distance restraint violation (Å) | 0.006020 +/− 0.001643 | |

| distance restraint violation >0.1 Å | 1.5 +/− 1.36 | |

| average dihedral restraint violation (°) | 0.2134 +/− 0.0452 | |

| dihedral restraint violation >1° | 3.00 +/− 1.00 | |

| deviation from ideal geometry | ||

| bond length (Å) | 0.000583 +/− 0.000061 | |

| bond angle (°) | 0.1160 +/− 0.0063 | |

| coordinate precision a,b | ||

| backbone heavy atoms (Å) | 0.93 | |

| all heavy atoms (Å) | 1.26 | |

| Ramachandran plot statisticsc (%) | 91.5/7.5/0.3/0.7 | |

aThe precision of the coordinates is defined as the average atomic root mean square difference between the accepted simulated annealing structures and the corresponding mean structure calculated for the given sequence regions.

bCalculated for residues Gly2-Val34, Ser41-Thr58, Lys69-Leu154.

cRamachandran plot statistics are determined by PROCHECK52 and noted by most favored/additionally allowed/generously allowed/disallowed.

Additionally, we performed structural overlays with various PR-10 allergens, Pru a v 1 from cherry, Gly m 4 from soy bean and the straberry allergen Fra a 1E, which all exhibit highly similar folds (see Supplementary Fig. S2). Only the length of the loops and the orientation and length of the structural elements are slightly different. One common feature of PR-10 allergens is the so-called glycine-rich loop, which is highly conserved in structure and sequence (see Supplementary Fig. S2), however its function has not been identified yet.

Identification of the natural ligand of Cor a 1 isolated from pollen

Recently, we were able to identify a natural ligand of the major birch pollen allergen Bet v 1, Q3OS, by co-purification of the allergen in complex with its ligand from pollen33. Natural Bet v 1 isolated from pollen consists of a mixture of different Bet v 1 isoallergens and variants thereof. Thus it is difficult to identify which protein(s) bind the ligand. Identification of the natural ligand contributes to the understanding of the function of PR-10 allergens in plants. To determine whether the same ligand can also be found in homologous PR-10 allergens, we purified the natural hazel allergen Cor a 1 from hazel pollen using a similar approach.

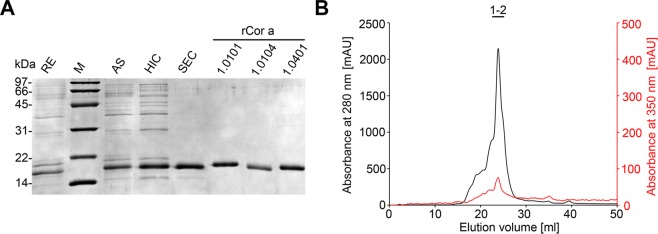

Natural Cor a 1 (nCor a 1) was extracted from mature hazel pollen derived from Corylus avellana and purified33,36. After each purification step, samples were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (Fig. 2A) (see Supplementary Fig. S3). Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) of pooled nCor a 1 fractions collected from a hydrophobic interaction column revealed two absorption maxima at an elution volume of 24 ml, one at 280 nm (protein) and the other one at 350 nm (ligand) (Fig. 2B). Pure SEC fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by mass spectrometry to identify the proteins present in the peak fractions.

Figure 2.

Purification of Cor a 1 from pollen. (A) Analysis of the purification procedure of Cor a 1 from hazel pollen by SDS-PAGE (19% gel). The sample after each purification step is shown: RE, raw extract; M, molecular weight marker (low range, Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany), the corresponding masses are indicated on the left; AS, resuspended pellet after precipitation with 100% ammonium sulfate saturation; HIC, pooled fractions after hydrophobic interaction chromatography; SEC, pure Cor a 1 sample after size exclusion chromatography; rCor a 1 represents the three recombinant purified forms Cor a 1.0101, 1.0104 and 1.0401. (B) SEC of purified nCor a 1. The absorbance at 280 nm (black line, protein) and 350 nm (red line, ligand) was recorded. Fractions 1-2, were pooled and loaded on the SDS-PA gel shown in (A).

Similarly to nBet v 1, nCor a 1 is composed of different isoallergens and variants and very likely additional ones will be identified. So far, not all known variants of Cor a 1 are detectable by mass spectrometry. We were able to confirm the presence of the variants Cor a 1.0103 and Cor a 1.0104 on the basis of variant specific tryptic peptides. Moreover, we detected Profilin 4, a member of a different allergen family. The proteins identified in nCor a 1 are summarized in Table 2. The detailed data on variant specific peptides and annotated spectra which unambiguously demonstrate the presence of Cor a 1.0103 and Cor a 1.0104 are displayed in Supplementary Table S2 and Fig. S4. Since the variants Cor a 1.0101 and Cor a 1.0102 do not contain unique tryptic peptides they are indistinguishable from Cor a 1.0103 and Cor a 10104. Thus, the presence of these variants can neither be confirmed nor be excluded. However, previous mRNA analyses by Breiteneder et al. using RT-PCR indicated their presence in hazel pollen22. The isoallergen Cor a 1.0401 could not be detected in our analysis.

Table 2.

Summary of MS data on natural and recombinant Cor a 1.

| internal | Genebank | UniProt | Description | S | SC | E | DP | MP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) purified nCor a 1 in gel | ||||||||

| PEI127 | X70998 | Q08407 | Cor a 1 0104, Corylus avellana | 7180 | 61.0 | 5.8 | 8 | 1 |

| PEI126 | X70997 | Q08407 | Cor a 1 0103, Corylus avellana | 5860 | 57.2 | 6.3 | 7 | 0 |

| PEI124 | X70999 | Q08407 | Cor a 1 0101, Corylus avellana | — | — | — | — | — |

| PEI125 | X71000 | Q08407 | Cor a 1 0102, Corylus avellana | — | — | — | — | — |

| n.a. | n.a. | A4KA45 | Profilin 4, Corylus avellana | 1723 | 40.6 | 7.2 | 3 | 0 |

| (b) rCor a 1.0401 in gel | ||||||||

| PEI 128 | n.a. | n.a. | rCor a 1 0401, Corylus avellana | 8489 | 88.8 | 6.0 | 15 | 1 |

| (c) rCor a 1.0102 in gel | ||||||||

| PEI 163 | X71000 | Q08407 | Cor a 1.0102, Corylus avellana | 1847 | 81.9 | 1.8 | 18 | 4 |

| (d) rCor a 1.0103 in gel | ||||||||

| PEI 161 | X70997 | Q08407 | Cor a 1.0103, Corylus avellana | 2963 | 81.3 | 1.3 | 15 | 3 |

n.a. not applicable; S: Score, SC: sequence coverage; E average precursor mass error; DP: number of detected tryptic peptides; MP: number of detected modified peptides.

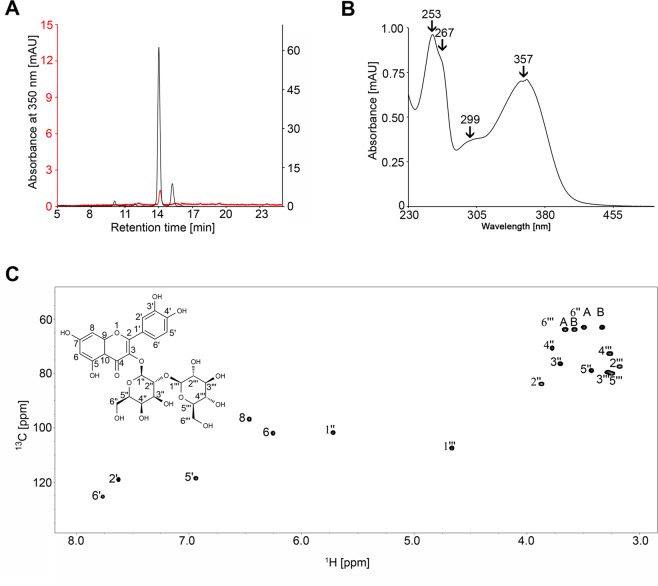

To identify the bound ligand, SEC fractions containing pure nCor a 1 were lyophilised and extracted with methanol. The extract was analysed both by liquid chromatography / mass spectrometry (LC/MS) (see Supplementary Fig. S5) and reversed phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) (Fig. 3A). The total ion current (TIC) chromatogram (see Supplementary Fig. S5) showed one peak apex at a retention time of 2.4 min exhibiting pseudomolecular ions of m/z = 627.155 [M + H]+, which is in good accordance with m/z = 627.156 for the putative molecular formula of the most abundant flavonoid in hazel pollen, Q3O-(Glc)-Gal [C27H30O17 + H]+ 37. RP-HPLC of the nCor a 1 extract yielded a single peak with a retention time of 14 min (Fig. 3A, red line). To increase the yield of the putative ligand we extracted the ligand directly from hazel pollen, i.e. without purifying the nCor a 1/ligand complex first (Fig. 3A, black line). We performed RP-HPLC and collected the peak fractions with the same retention time, and analyzed them further by UV-Vis spectroscopy (Fig. 3B), mass spectrometry, and NMR spectroscopy (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

Identification of the natural ligand Q3O-(Glc)-Gal. (A) RP-HPLC chromatogram of hazel pollen extract (black line) and the ligand of nCor a 1 isolated from pure SEC fractions (red line) using a C18A column. (B) UV/Vis spectrum of the ligand purified from pollen. Absorption maxima at 253 nm, 267 nm, 299 nm, and 357 nm are indicated. (C) 1H, 13C HSQC spectrum of the ligand purified from pollen in d6-DMSO. The structure is shown on the top left. A and B indicate the two different hydrogen atoms at positions 6″ and 6″′, respectively.

The UV-Vis spectrum of the ligand in methanol exhibited absorption maxima at 256, 269, 299 and 357 nm (Fig. 3B), in excellent agreement with UV-Vis spectra of the glycosylated flavonoid Q3O-(Glc)-Gal in methanol reported previously37. The TIC (total ion current) chromatogram of the ligand isolated directly from hazel pollen also confirmed the presence of Q3O-(Glc)-Gal (data not shown).

To further characterize the purified ligand, 1H and 13C chemical shifts were obtained from a 1H, 13C heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectrum in deuterated DMSO (d6-DMSO) (Fig. 3C). The NMR resonances agree well with published data37 and confirmed the identity of this glycosylated flavonoid in the β-glycosidic form. Ligand identification was reproducible using three different pollen batches.

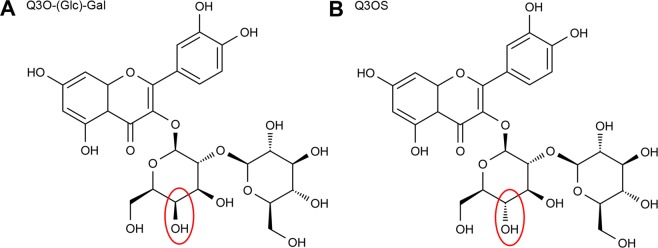

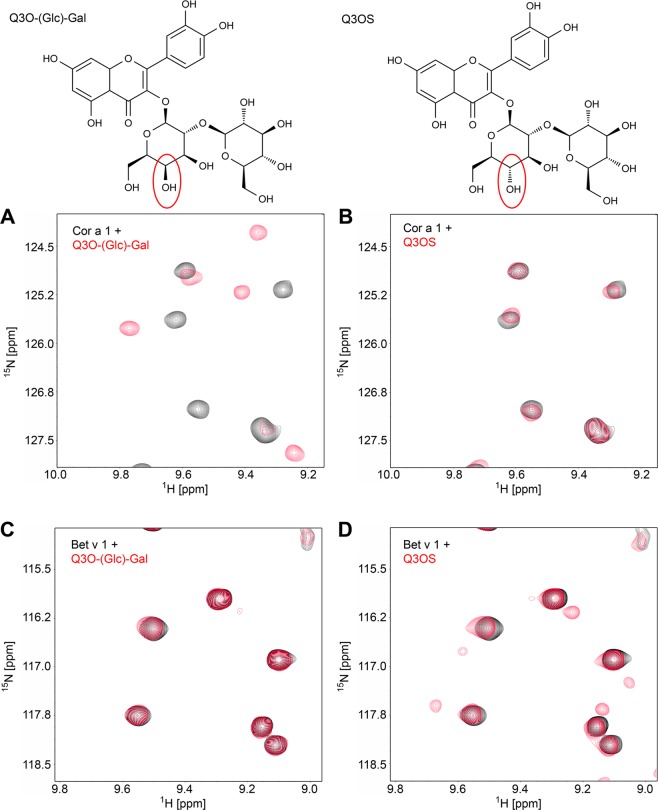

Interestingly, this ligand is very similar to the epimeric Bet v 1 ligand Q3OS. The only difference is the orientation of the hydroxyl group at the C4 of the first sugar moiety resulting in a glucose moiety in Q3OS vs a galactose moiety in Q3O-(Glc)-Gal linked to quercetin (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Structural comparison of Q3OS and Q3O-(Glc)-Gal.

Binding of rCor a 1 isoallergens to Q3O-(Glc)-Gal

To learn more about the binding properties of the ligand we analysed its interaction with different rCor a 1 proteins. The high sensitivity of the chemical shift to structural changes makes NMR spectroscopy a powerful tool to investigate ligand binding to a protein as binding of a ligand causes structural changes at least in the binding region. This can be easily observed by comparison of NMR spectra of the protein before and after addition of the ligand.

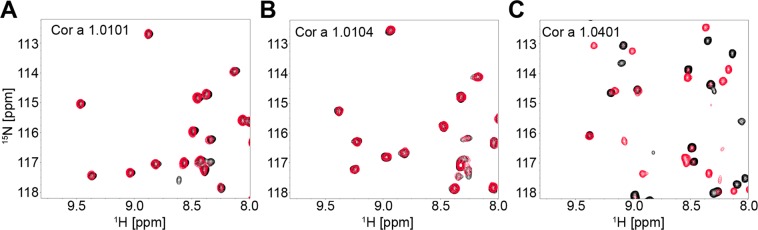

We decided to further analyse four known Cor a 1 variants previously detected in hazel pollen and one detected in hazel nut7. Thus, we purified the 15N labelled variants rCor a 1.0101, rCor a 1.0102, rCor a 1.0103, rCor a 1.0104 (pollen), and rCor a 1.0401 (nut) from E. coli to perform binding experiments by two-dimensional protein NMR spectroscopy. 1H, 15N HSQC spectra of the proteins were recorded before and after the addition of a ten-fold molar excess of Q3O-(Glc)-Gal. The spectra of the four Cor a 1 variants from pollen did not show changes even with a ten-fold excess of ligand, indicating no binding. This is exemplary shown for rCor a 1.0101 and rCor a 1.0104, (Fig. 5A,B). In contrast, binding could be observed to rCor a 1.0401 (Fig. 5C) corroborating Q3O-(Glc)-Gal as a ligand.

Figure 5.

Binding of Q3O-(Glc)-Gal to different Cor a 1 isoallergens. Overlay of two 1H-15N spectra of 60 µM of Cor a 1 isoallergens in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0 in the absence (black) or presence of a ten-fold molar excess of Q3O-(Glc)-Gal (red) recorded at a Bruker Avance 700 MHz spectrometer at 298 K (A) Cor a 1.0101, (B) Cor a 1.0104, and (C) Cor a 1.0401. Upon ligand addition no significant shifts can be observed for Cor a 1.0101 and Cor a 1.0104, implying no or weak binding, whereas with Cor a 1.0401, the signal intensity of many residues decreases and new signals appear, indicating binding.

Cor a 1.0401 was previously shown to be present in hazelnut7. To determine whether Cor a 1.0401 is also present in pollen, crude pollen extracts were analyzed by mass spectrometry to avoid loss of individual Cor a 1 isoallergens or variants, which may have occurred during purification of nCor a 1. However, the results matched the ones of purified nCor a 1. We found Cor a 1.0104 and Cor a 1.0103 to be accompanied by Profilin 4 and 5, and several other non allergenic proteins, but not by Cor a 1.0401 (Table S3). Our results indicate that Cor a 1.04 variants are either absent in hazel pollen or they are only present at concentrations below the detection limit. Since rCor a 1.0401 binds Q3O-(Glc)-Gal with high specificity other still unknown Cor a 1 isoallergens may be present in hazel pollen as well as in purified nCor a 1 and bind to the ligand.

Contrariwise, HPLC analyses of hazelnut skin extracts were negative for Q3O-(Glc)-Gal (see Supplementary Fig. S6). This is in line with earlier experiments that introduced 3-O-(2″-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl)-β-D-galactopyranoside conjugates of kaempferol and quercetin as a pollen-specific class of glycosylated flavonoids38,39.

Binding of Q3O-(Glc)-Gal to Cor a 1.0401

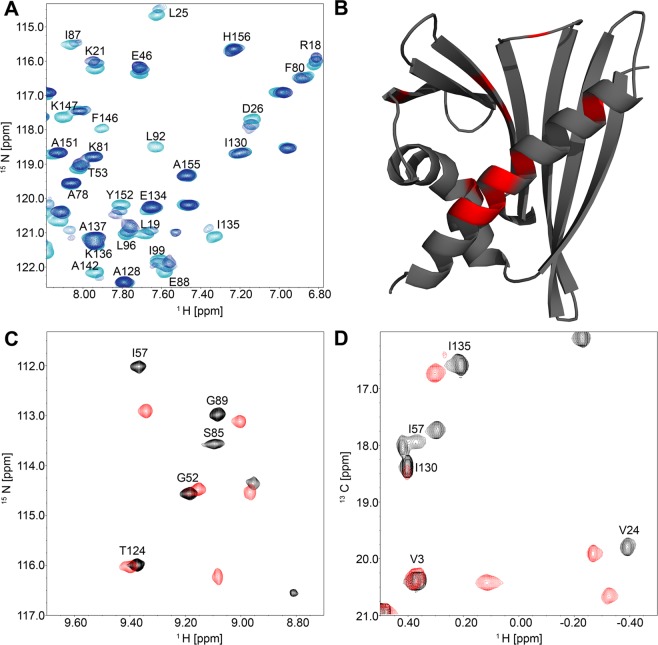

To investigate binding of quercetin, which lacks the sugar moiety, to the hydrophobic pocket of Cor a 1.0401, a titration was performed and 1H, 15N HSQC spectra were recorded after each step (Fig. 6A). While some signals (F146, L92) disappeared, indicating binding in the intermediate or slow exchange regime, others shifted with each titration step (Y152, R18, K21). This is characteristic for binding in the fast exchange resulting in the observation of population-averaged chemical shifts between ligand-bound and unbound protein. The residues which disappeared and therefore were affected most by binding were mapped on the solution structure of Cor a 1.0401 (Fig. 6B). Remarkably, binding of quercetin to Bet v 1.0101 revealed similar, but not identical binding interfaces33.

Figure 6.

NMR titration of Cor a 1.0401 with quercetin and Q3O-(Glc)-Gal. All experiments were performed with a Bruker Avance 700 MHz spectrometer at 298 K with 60 to 100 μM Cor a 1.0401 uniformly labelled with 15N and 13C. (A) Overlay of three 1H-15N HSQC spectra of Cor a 1.0401 in the presence of increasing quercetin concentrations, from light to dark blue; ligand to protein ratio: 0, 0.5 and 1. The quercetin stock solution was prepared in d6-DMSO to obtain a final DMSO concentration of 2.2% (v/v). (B) Cartoon representation of Cor a 1.0401. The amino acids that were strongest affected by quercetin binding are highlighted in red. (C) Section of an overlay of two 1H, 15N HSQC spectra of Cor a 1.0401 in the absence (black) and presence (red) of an 8-fold excess of Q3O-(Glc)-Gal. (D) Section of an overlay of two 1H, 13C HSQC spectra of Cor a 1.0401 in the absence (black) and presence (red) of an 8-fold excess of Q3O-(Glc)-Gal.

To further investigate binding of Q3O-(Glc)-Gal to Cor a 1.0401, a titration of Q3O-(Glc)-Gal to 15N, 13C labeled protein was performed and after each step, 1H, 15N HSQC as well as 1H, 13C HSQC spectra were recorded. Figure 6C,D show overlays of the 1H, 15N and 1H, 13C HSQC spectra, respectively, in the absence of ligand and after the addition of the highest ligand concentration.

During titration, about 80% of all signals disappeared and reappeared somewhere else in the spectrum, which is characteristic for binding in the slow exchange regime. Upon binding of the ligand to the protein, the affected nuclear spins change between at least two states (bound and unbound state) with different chemical shifts. The effect of the exchange on the spectrum depends on the relation between the off rate and the magnitude of the chemical shift difference in Hertz. Observation of spectra in the slow exchange regime implies that the off rate is smaller than the chemical shift difference. A small off rate means slow dissociation of the ligand from the protein, indicating rather strong binding with dissociation constants typically below 5 µM40. However, it was not possible to determine exact dissociation constants. As about 80% of all signals were strongly affected by binding, it was also impossible to determine a binding interface. This extreme change in the spectrum could either point towards a structural rearrangement of Cor a 1.0401 upon ligand binding or a rearrangement of the side chains, which influence the chemical environment of the nuclear spins.

Confirmation of specific ligand binding by two-dimensional NMR experiments

It is often stated that PR-10-proteins show promiscuous binding behaviour16,18,19. To investigate binding specificities, a set of two dimensional NMR-experiments was performed with Bet v 1.0101 and Cor a 1.0401 in the presence and absence of the corresponding natural ligands (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Binding specificity of Bet v 1.0101 and Cor a 1.0401. The structures of Q3O-(Glc)-Gal (left) and Q3OS (right) are shown on top of the panels. Section of overlays of 1H-15N HSQC spectra of Cor a 1.0401 or Bet v 1.0101 in the absence or presence of ligand: Cor a 1.0401 with (A) Q3O-(Glc)-Gal or (B) Q3OS; Bet v 1.0101 with (C) Q3O-(Glc)-Gal or (D) Q3OS.

Most surprisingly, Cor a 1.0401 only binds to Q3O-(Glc)-Gal (Fig. 7A,B), whereas Q3OS binding is specific for Bet v 1.0101 (Fig. 7C,D), even though the amino acid identity of the two proteins is rather high (67.3%) and the only difference between the two ligands is the orientation of the OH-group in the respective sugar moiety (glucose vs. galactose). However, the physiological roles and functions of the different binding specificities remain to be elucidated.

The high binding specificities of Bet v 1 and Cor a 1 variants allow the discrimination between the natural ligand and a highly similar, epimeric ligand of the homologous allergen (Fig. 7). A similar substrate specificity can be observed in glycosyl transferases that are responsible for glycosylation and deglycosylation of flavonoids in pollen38. A single point mutation of the UDP-galactose galactosyltransferase from Aralia cordata (H374Q) changed the preferential donor from galactose to glucose41.

Ligand discrimination might already take place at the entrance to the hydrophobic pocket. The largest opening is located between T58 and Y67. In this region there are three amino acid exchanges between Bet v 1.0101 and Cor a 1,0401, P59A, L62N and P63E, which might play a role in ligand discrimination. However, to explain the molecular basis of the highly selective ligand binding, complex structures of both proteins are needed.

Conclusions

Despite the high clinical relevance of the hazel allergen Cor a 1, physiological and structural knowledge is scarce. The solution structure of the variant Cor a 1.0401, which we present here, provides the basis for future immunological and physiological studies since Cor a 1.0401 is one of the strong IgE binding variants7.

Moreover, we identified Q3O-(Glc)-Gal as a natural ligand of Cor a 1.0401. Our findings demonstrate binding of rCor a 1.0401 usually found in hazelnut to the pollen specific ligand Q3O-(Glc)-Gal. This might be explained by the unusual reproduction biology of hazel. Within 4–7 days after pollination in January and February the pollen grows to the base of the style, which connects the stigma with the ovary. Here, the tip of the tube enters a long resting period of several months. The ovary grows over ca. 5 months until it becomes mature and contains egg cells. The resting sperm becomes activated and after growth of secondary pollen tubes, fertilization takes place. This results in rapid growth of the kernel over a period of 6 weeks42.

Glycosylated flavonoids comprise a storage form, whereas the aglycons are functionally active and are indispensable for the formation of the pollen tube38,43. Thus, we propose that upon first contact of hazel pollen with the stigma, Q3O-(Glc)-Gal from pollen and Cor a 1.0401 from the stigma might form a complex persisting throughout the maturation of the ovules. Formation of the complex is necessary to prevent premature deglycosylation of Q3O-(Glc)-Gal to quercetin by glycosyltransferases. After maturation, the ligand is released and converted into quercetin, which might then assist the formation of the secondary pollen tube43,44. A prerequisite of this hypothesis is, of course, that Cor a 1.0401 is already present in the stigma and is not only expressed during kernel formation. However, this has not been tested yet.

Nevertheless, a yet unidentified Cor a 1 isoallergen bound to Q3O-(Glc)-Gal is present in hazel pollen, since SEC showed that the ligand (627 Da) and nCor a 1 (17 kDa) co-purify in one peak and moreover, we were able to isolate the ligand Q3O-(Glc)-Gal from highly purified nCor a 1. Although peptide mass fingerprint by LC-MSE is a powerful method to identify already known proteins, uncharacterized Cor a 1 isoallergens will not be discovered by this method. It is highly probable that there are more Cor a 1 isoallergens to be found in the future. For Bet v 1, which is the PR-10 allergen investigated most thoroughly, 18 isoallergens have been unambiguously identified so far45.

The binding specificity of Bet v 1.0101 and Cor a 1.0401 for their natural ligands, Q3OS and Q3O-(Glc)-Gal, respectively, as well as the fact that the other Cor a 1 variants rCor a 1.0101 and rCor a 1.0104 do not bind Q3O-(Glc)-Gal suggests that despite their high sequence identity and structural similarity, Bet v 1 homologous proteins and variants bind to different ligands and might even fulfil different physiological functions. This might be the reason why a precise function of Bet v 1 homologous proteins could not be identified so far.

Materials and Methods

Polyphenols

Quercetin was purchased in analytical grade from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA), and Q3OS from Phytolab (Vestenbergsgreuth, Germany). Q3O-(Glc)-Gal was purified from hazel pollen extracts (Allergon, Ängelholm, Sweden). To extract the flavonoids, pollen was dissolved in H2O (500 mg dry wt/10 ml H2O), stirred at room temperature for 3 h and centrifuged (20 min, 4 °C, 10000 × g). The supernatant was collected and the pellet was redissolved in 10 ml H2O, and treated as described above. The procedure was repeated and the extract stirred over night. H2O extracts were evaporated to dryness in vacuo and the pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of 61% solvent A (2% v/v acidic acid) and 39% solvent B (0.5% v/v acidic acid, 50% v/v acetonitrile), centrifuged and filtered through a nylon filter (45 µm; Phenomenex, Aschaffenburg, Germany). The compounds were purified by HPLC by isocratic elution with 61% solvent A and 39% solvent B using a C18 column (SP 250/21 Nucleosil 100–7; Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) at a flow rate of 10 ml/min. Fractions containing ligands were evaporated to dryness in vacuo afterwards. The purified compounds were stored at 4 °C in the dark. Q3O-(Glc)-Gal content was measured by the absorbance at 350 nm, for quantitative calculations the extinction coefficient of Q3OS (ε350 = 13500 M−1 cm−1) was used.

For the analysis of polyphenols from hazelnut skin, the skins were removed from the nuts (type “Barcelona”, origin: USA) with a scalpel and dried overnight at 50 °C. Afterwards, they were shock frozen and grinded using a porcelain mortar. 250 mg of the grinded hazelnut skins was then extracted with 10 ml 100% methanol over night, the extract centrifuged, the supernatant dried in vacuo and redissolved in 2 ml of 90% solvent A (2% v/v acidic acid) and 10% solvent B (0.5% v/v acidic acid, 50% v/v acetonitrile). After centrifugation and filtration through a 45 µM nylon filter (Phenomenex, Aschaffenburg, Germany), the extract was analysed by RP-HPLC using a gradient from 10% B to 100% B within 35 min.

Cloning, expression and protein preparation

Synthetic genes coding for Cor a 1.0101; Cor a 1.0104 (Genescript, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA) and Cor a 1.0401 (optimized for codon-usage in E. coli) were cloned via NdeI, BamHI into the expression vector pET11a (Novagen-Merck, Germany). To obtain Cor a 1.0102 and Cor a 1.0103, plasmids pET11a Cor a 1.0104 and pET11a Cor a 1.0101, respectively, were used as templates for site-directed mutagenesis according to the QuickChange Method Cornell iGEM 2012” protocol (http://2012.igem.org/wiki/images/a/a5/Site_Directed_Mutagenesis.pdf).

Gene expression for all unlabelled, 15N, and 15N, 13C labelled allergens was performed as described previously for pET11a_Bet v 1a (Bet v 1.0101)33 using (15NH4)2SO4 and 13C-glucose. An amino acid sequence alignment of the Cor a 1 and Bet v 1 proteins used in this study is shown in Supplementary Fig. S7. The protein bank entry accession numbers and a sequence identity matrix of the proteins are listed in Supplementary Table S4.

Purification of recombinant proteins

Protein purification for Cor a 1.0101, Cor a 1.0401, and Bet v 1.0101 was performed as described for Bet v 1 a (Bet v 1.0101)33 with the following modifications: For Cor a 1.0101, streptomycin sulfate was added to a final concentration of 1% to precipitate nucleic acids. 1.5 M (NH4)2SO4 was then added to the protein solution, and the solution was loaded on to a 5 ml octylsepharose column (Octylsepharose 4 Fast Flow; GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany) equilibrated with 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 1.5 M (NH4)2SO4, and eluted using a gradient from 0 to 60% elution buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0) followed by a step to 100% elution buffer.

Cor a 1.0102, Cor a 1.0103, or Cor a 1.0104 containing cell extracts were centrifuged (19000 g, 30 min, 4 °C) and the pellet was resuspended in 50 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.8, 500 mM NaCl and 8 M urea. The denatured protein was refolded by stepwise lowering the urea concentration during dialysis to 4 M, 2 M, 1 M for 1 h and dialysis for 4 h and over night in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0.

To remove remaining contaminants identified by 1H, 15N HSQC spectra, purified Bet v 1.0101, was unfolded using 8 M urea, 50 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.0, 50 mM NaCl for 1.5 h at room temperature. After centrifugation of the sample in a Vivaspin concentrator 20 (MWCO 10 kDa, Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Göttingen, Germany), 20 ml of buffer without urea was added to the remaining solution. After centrifugation the procedure was repeated and the sample was then concentrated to 1 ml. The pure proteins were either shock frozen and stored at −80 °C or dialysed against Milli Q H2O, lyophilised and stored at 4 °C.

Protein analysis

Standard methods were used to analyse purity (SDS-PAGE), oligomeric state (SEC) and structural integrity (1D-NMR, 1H-15N HSQC spectroscopy for the 15N labelled proteins) of all variants. The proteins were stored as described above.

Purification of nCor a 1 from pollen of Corylus avellana and ligand isolation

nCor a 1 was purified from hazel pollen (Allergom, Ängelholm, Sweden) as described previously for the isolation of Bet v 1 from birch pollen33,36 with minor changes, using ammonium sulfate precipitation (50%, 60% and 100% (NH4)2SO4 saturation), followed by hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC) as described above for the purification of recombinant Cor a 1.0101 but with only one purification step with 100% elution buffer. To remove remaining impurities, Cor a 1-containing HIC-fractions were concentrated (Vivaspin 20 concentrator, molecular-mass cut-off 3000 Da) to a final volume of 500 µl and loaded on to two consecutively connected Superdex 75 10/300 GL columns (24 ml bed volume each; GE Healthcare, Penzberg, Germany), equilibrated with a buffer containing 10 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.0, and 300 mM NaCl. If required, another HIC chromatography using a step gradient was performed. The nCor a 1 fractions were pooled, concentrated and lyophilised.

Subsequently, the prominent protein band at 17 kDa on an SDS polyacrylamide gel was excised and the protein was analysed by tryptic digestion followed by liquid chromatography – mass spectrometry (LC-MSE) to confirm its identity.

For ligand isolation pure Cor a 1 fractions were lyophilised and redissolved in methanol. The methanol extract was dried in vacuo, redissolved in 50 µl 2,5% methanol and analyzed by RP- HPLC using a 150 × 4 mm 5 µm C18A vertex plus column with a pore size of 100 Å (Knauer, Berlin, Germany), equilibrated with solvent A (2% acetic acid) followed by a gradient from 10% to 90% solvent B (0,5% acetic acid, 50% acetonitrile) within 35 min, and analysed by mass spectrometry.

Mass spectrometric confirmation of Cor a 1 isoallergens and variants

The isoallergen and variant composition of purified nCor a 1 and the identity of purified rCor a 1.0102, rCor a 1.0103 and rCor a 1.0401 were determined by nano-UPLC (ultra performance liquid chromatography) nano-ESI MSE (electron spray ionisation mass spectrometry)46 after SDS-PAGE separation and in gel digestion47 as published previously45 using an in-house database consisting of reviewed entries of the UniProt database (as at January 2016) (Table 2). The isoallergen and variant composition of crude hazel pollen extract was determined by nano-UPLC nano ESI MSE 46 after in solution tryptic digestion as published previously24, except that we used the above mentioned in-house database for analyses. Three different crude extracts were obtained by extracting proteins from hazel pollen following an extraction protocol applied previously on birch pollen45. Differing from this, three buffers were used. Sample (a): sodium phosphate buffer33, (b): 100 mM NH4HCO3-buffer45 and (c): 8 mM Tris and 10 mM (NH4)2B10O16*8H2O.

Mass spectrometry of the ligand Q3O-(Glc)-Gal

For MS analysis, the purified ligand extracted from hazel pollen was loaded on a HPLC RP-C18 column (Phenomenex Inc. USA, Kinetex 5 µm EVO C18, 100 Å, 30 × 2.1 mm) which was connected to a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific GmbH, Bremen, Germany) with a hybrid quadrupole orbitrap mass analyzer (maximum mass range 50–6000 Da, resolution 140.000 @ m/z = 200), using a gradient from 20–95% acetonitrile within 10 min. Mass spectra were acquired after (positive mode) electrospray ionisation (ESI pos) in full scan mode (70–1050 amu) recording the TIC.

To confirm the presence of the ligand of the purified nCor a 1, the methanol extract of nCor a 1 after SEC was loaded onto a C18 column (Accucore RP-MS, 2.6 µm, 150 × 2.1 mm) connected to the Q Exactive mass spectrometer. Isocratic elution was performed with 50% acetonitrile within 20 min. Mass spectra were acquired as described above.

NMR experiments

All NMR-experiments were performed at 298 K on Bruker Avance spectrometers with proton resonance frequencies of 600, 700, 900 and 1000 MHz, the latter three equipped with cryogenically cooled triple resonance probes.

NMR-spectroscopy of ligands

1H-NMR and 13C NMR spectroscopy of about 3 mM Q3O-(Glc)-Gal in d6-DMSO was performed at 600 MHz 1H frequency. Chemical shifts were referenced to tetramethylsilane. Data was processed using Topspin version 3.2 (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany).

Determination of the solution structure of Cor a 1.0401 and Bet v 1.0101

Resonance assignments were done with standard double- and triple-resonance through-bond correlation experiments. Threedimensional NMR experiments of Cor a 1.0401 were recorded using non-uniform sampling (NUS) with 25% data amount. NMR-spectra to assign chemical shifts were obtained with a 600 µM [1H, 13C, 15N] Cor a 1.0401 sample in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 10% (v/v) D2O, 0.03% NaN3 and 2 mM DTT. Three-dimensional 13C and 15N edited nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY) experiments (mixing times 120 ms) were recorded for derivation of distance restraints. NMR data were processed using in-house software and visualized with NMRViewJ (OneMoon Scientific, Inc.). Iterative soft thresholding was applied for processing NUS NMR experiments48.

NOESY cross peaks were classified according to their relative intensities and converted into distance restraints with upper limits of 3.0 Å (strong), 4.0 Å (medium), 5.0 Å(weak) and 6.0 Å (very weak). Dihedral restraints were taken from analysis of chemical shifts by the TALOS software package49. Structures were calculated using the programme XPLOR-NIH50,51. The 20 structures showing the lowest overall energy were analysed with XPLOR-NIH and PROCHECK-NMR52.

Binding experiments

To investigate the binding interface of Cor a 1.0401 upon binding of quercetin, quercetin was dissolved in DMSO and added in different concentrations to 60 µM13 C15 N Cor a 1.0401, up to an equimolar concentration. The DMSO concentration of the final NMR sample was always 2,2%. To identify chemical shift perturbations caused by DMSO, a sample was prepared with 60 µM13 C15 N Cor a 1.0401 and 2.2% DMSO. 1H, 15N HSQCs of each sample were recorded. Where binding in the fast exchange rate occurred, chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) resulting from ligand binding were calculated based on equation (1):

∆δHN and ∆δN, chemical shift differences of amide proton and nitrogen resonances, respectively, in ppm.

Where binding in the slow exchange rate occurred, the relative intensities of each signal were compared to the corresponding signal in the reference spectrum without ligand.

For titration of Q3O-(Glc)-Gal to Cor a 1.0401, a 9.9 mM stock solution of Q3O-(Glc)-Gal in 10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0 was prepared and added stepwise to 100 µM of 13C, 15N Cor a 1.0401 up to an 8-fold molar excess. After each titration step, a 1H, 15N HSQC and a 1H, 13C HSQC spectrum was recorded.

Binding specificity of Bet v 1.0101, Cor a 1.0401, Cor a 1.0101 and Cor a 1.0104 was investigated by recording 1H, 15N HSQCs of 60 µM of the respective 15N-labelled protein in the absence and in the presence of a ten-fold molar excess of Q3OS or Q3O-(Glc)-Gal.

Computational methods

Figures of protein structures were generated and homologous protein structures were aligned using the programme PyMOL Molecular graphics System, Version 1.5.0.4. Theoretical isoelectric points, extinction coefficients and molecular weight of the different PR-10 proteins were determined using the ProtParam Tool53. For the calculation of the cavity volumes, the programme CastP54 was used with default parameters. They were determined for every single structure of the NMR bundle and are given as means + − S.D. Multiple and pairwise sequence alignments were performed with ClustalOmega55 and EMBOSS Needle56.

Data deposition

Coordinates and restraints for structure calculation of Cor a 1.0401 and Bet v 1.0101 were deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) under the accession codes 6GQ9 and 6R3C, respectively. Chemical shift assignments were deposited in the BioMagResBank: accession numbers 34281(Cor a 1.0401) and 34383 (Bet v 1.0101).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ramona Heissmann, Andrea Hager, Luisa Schwaben, and Elke Völker for excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by the University of Bayreuth and the Paul-Ehrlich-Institut.

Author Contributions

B.M.W. and T.J. wrote the manuscript. P.R. and S.V. initiated the project and provided conceptual input. C.S.v.L., K.S. and B.M.W. supervised the project and designed experiments. C.S.v.L. and T.J. carried out the expression and purification experiments. C.S.v.L., K.S. and T.J. performed the NMR experiments and evaluated the data. K.S. solved the solution structure of Bet v 1.0101. D.S. cloned and sequenced rCor a 1.0401, A.R. performed the MS analyses of rCor a 1.0401, nCor a 1 and hazel pollen extract. U.L. and R.S. performed the mass spectrometry of the ligand and evaluated the data. V.M. contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data. All authors contributed in preparing the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-44999-2.

References

- 1.Datema MR, et al. Hazelnut allergy across Europe dissected molecularly: A EuroPrevall outpatient clinic survey. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;136:382–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ortolani C, Pastorello EA. Food allergies and food intolerances. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2006;20:467–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burney P, et al. Prevalence and distribution of sensitization to foods in the European Community Respiratory Health Survey: a EuroPrevall analysis. Allergy. 2010;65:1182–1188. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burney PGJ, et al. The prevalence and distribution of food sensitization in European adults. Allergy. 2014;69:365–371. doi: 10.1111/all.12341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Etesamifar M, Wüthrich B. IgE-vermittelte Nahrungsmittelallergien bei 383 Patienten unter Berücksichtigung des oralen Allergiesyndroms. Allergologie. 1998;21:451–457. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breiteneder H, Radauer C. A classification of plant food allergens. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004;113:821–830. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.01.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lüttkopf D, et al. Comparison of four variants of a major allergen in hazelnut (Corylus avellana) Cor a 1.04 with the major hazel pollen allergen Cor a 1.01. Mol. Immunol. 2002;38:515–525. doi: 10.1016/S0161-5890(01)00087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lauer I, et al. Expression and characterization of three important panallergens from hazelnut. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008;52(Suppl 2):S262–271. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eriksson NE, Formgren H, Svenonius E. Food hypersensitivity in patients with pollen allergy. Allergy. 1982;37:437–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1982.tb02323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breda C, et al. Defense reaction in Medicago sativa: a gene encoding a class 10 PR protein is expressed in vascular bundles. Mol. Plant. Microbe Interact. 1996;9:713–719. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-9-0713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robert N, et al. Molecular Characterization of the Incompatible Interaction of Vitis Vinifera Leaves With Pseudomonas Syringae Pv. Pisi: Expression Of Genes Coding For Stilbene Synthase And Class 10 PR Protein. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2001;107:249–261. doi: 10.1023/A:1011241001383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jain S, Kumar A. The Pathogenesis Related Class 10 proteins in Plant Defense against Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Adv. Plants Agric. Res. 2015;2:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walter MH, Liu JW, Grand C, Lamb CJ, Hess D. Bean pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins deduced from elicitor-induced transcripts are members of a ubiquitous new class of conserved PR proteins including pollen allergens. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1990;222:353–360. doi: 10.1007/BF00633840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebner C, Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, Breiteneder H. Plant food allergens homologous to pathogenesis-related proteins. Allergy. 2001;56(Suppl 67):43–44. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffmann-Sommergruber K. Plant allergens and pathogenesis-related proteins. What do they have in common? Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2000;122:155–166. doi: 10.1159/000024392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mogensen JE, Wimmer R, Larsen JN, Spangfort MD, Otzen DE. The major birch allergen, Bet v 1, shows affinity for a broad spectrum of physiological ligands. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:23684–23692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marković-Housley Z, et al. Crystal structure of a hypoallergenic isoform of the major birch pollen allergen Bet v 1 and its likely biological function as a plant steroid carrier. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;325:123–133. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)01197-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koistinen KM, et al. Birch PR-10c interacts with several biologically important ligands. Phytochemistry. 2005;66:2524–2533. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kofler S, et al. Crystallographically mapped ligand binding differs in high and low IgE binding isoforms of birch pollen allergen bet v 1. J. Mol. Biol. 2012;422:109–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asam C, et al. Bet v 1–a Trojan horse for small ligands boosting allergic sensitization? Clin. Exp. Allergy J. Br. Soc. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014;44:1083–1093. doi: 10.1111/cea.12361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirschwehr R, et al. Identification of common allergenic structures in hazel pollen and hazelnuts: a possible explanation for sensitivity to hazelnuts in patients allergic to tree pollen. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1992;90:927–936. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90465-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breiteneder H, et al. Four recombinant isoforms of Cor a I, the major allergen of hazel pollen, show different IgE-binding properties. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;212:355–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, et al. Genomic characterization of members of the Bet v 1 family: genes coding for allergens and pathogenesis-related proteins share intron positions. Gene. 1997;197:91–100. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(97)00246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spiric J, et al. Model for Quality Control of Allergen Products with Mass Spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2017;16:3852–3862. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ipsen H, Løwenstein H. Isolation and immunochemical characterization of the major allergen of birch pollen (Betula verrucosa) J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1983;72:150–159. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(83)90523-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swoboda I, et al. Isoforms of Bet v 1, the major birch pollen allergen, analyzed by liquid chromatography, mass spectrometry, and cDNA cloning. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:2607–2613. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.6.2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faber C, et al. Secondary structure and tertiary fold of the birch pollen allergen Bet v 1 in solution. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:19243–19250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferreira F, et al. Modulation of IgE reactivity of allergens by site-directed mutagenesis: potential use of hypoallergenic variants for immunotherapy. FASEB J. 1998;12:231–242. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.2.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krebitz M, et al. Rapid production of the major birch pollen allergen Bet v 1 in Nicotiana benthamiana plants and its immunological in vitro and in vivo characterization. FASEB J. 2000;14:1279–1288. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.10.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mirza O, et al. Dominant epitopes and allergic cross-reactivity: complex formation between a Fab fragment of a monoclonal murine IgG antibody and the major allergen from birch pollen Bet v 1. J. Immunol. 2000;165:331–338. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spangfort MD, et al. Dominating IgE-binding epitope of Bet v 1, the major allergen of birch pollen, characterized by X-ray crystallography and site-directed mutagenesis. J. Immunol. 2003;171:3084–3090. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gajhede M, et al. X-ray and NMR structure of Bet v 1, the origin of birch pollen allergy. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1996;3:1040–1045. doi: 10.1038/nsb1296-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seutter von Loetzen C, et al. Secret of the major birch pollen allergen Bet v 1: identification of the physiological ligand. Biochem. J. 2014;457:379–390. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seutter von Loetzen C, et al. Ligand Recognition of the Major Birch Pollen Allergen Bet v 1 is Isoform Dependent. PloS One. 2015;10:e0128677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seutter von Loetzen C, Schweimer K, Schwab W, Rösch P, Hartl-Spiegelhauer O. Solution structure of the strawberry allergen Fra a 1. Biosci. Rep. 2012;32:567–575. doi: 10.1042/BSR20120058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bollen MA, et al. Purification and characterization of natural Bet v 1 from birch pollen and related allergens from carrot and celery. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2007;51:1527–1536. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strack D, et al. Quercetin 3-glucosylgalactoside from pollen of Corylus avellana. Phytochemistry. 1984;23:2970–2971. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(84)83059-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller KD, Guyon V, Evans JN, Shuttleworth WA, Taylor LP. Purification, cloning, and heterologous expression of a catalytically efficient flavonol 3-O-galactosyltransferase expressed in the male gametophyte of Petunia hybrida. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:34011–34019. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.48.34011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.R. Markham K, Campos M. 7- And 8-O-methylherbacetin-3-O-sophorosides from bee pollens and some structure/activity observations. Phytochemistry. 1996;43:763–767. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(96)00286-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts, G. C. K. BioNMR in drug research. (Wiley-VCH, 2003).

- 41.Kubo A, Arai Y, Nagashima S, Yoshikawa T. Alteration of sugar donor specificities of plant glycosyltransferases by a single point mutation. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004;429:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olsen, J. L. Growing Hazelnuts in the Pacific Northwest: Pollination and Nut Development. OSU Ext. Cat. 1–4 (2013).

- 43.Mo Y, Nagel C, Taylor LP. Biochemical complementation of chalcone synthase mutants defines a role for flavonols in functional pollen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:7213–7217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogt T, Taylor LP. Flavonol 3-O-glycosyltransferases associated with petunia pollen produce gametophyte-specific flavonol diglycosides. Plant Physiol. 1995;108:903–911. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.3.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spiric J, Engin AM, Karas M, Reuter A. Quality Control of Biomedicinal Allergen Products - Highly Complex Isoallergen Composition Challenges Standard MS Database Search and Requires Manual Data Analyses. PloS One. 2015;10:e0142404. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silva JC, et al. Quantitative proteomic analysis by accurate mass retention time pairs. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:2187–2200. doi: 10.1021/ac048455k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M. Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 1996;68:850–858. doi: 10.1021/ac950914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hyberts SG, Milbradt AG, Wagner AB, Arthanari H, Wagner G. Application of iterative soft thresholding for fast reconstruction of NMR data non-uniformly sampled with multidimensional Poisson Gap scheduling. J. Biomol. NMR. 2012;52:315–327. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9611-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen Y, Delaglio F, Cornilescu G, Bax A. TALOS+: a hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J. Biomol. NMR. 2009;44:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Tjandra N, Clore GM. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/S1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski JJ, Clore GM. Using Xplor–NIH for NMR molecular structure determination. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2006;48:47–62. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2005.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laskowski RA, Rullmannn JA, MacArthur MW, Kaptein R, Thornton JM. AQUA and PROCHECK-NMR: programs for checking the quality of protein structures solved by NMR. J. Biomol. NMR. 1996;8:477–486. doi: 10.1007/BF00228148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gasteiger, E. et al. Protein Identification and Analysis Tools on the ExPASy server. in The Proteomics Protocols Handbook 571–607 (Humana Press, 2005).

- 54.Dundas J, et al. CASTp: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins with structural and topographical mapping of functionally annotated residues. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W116–118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sievers F, et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2011;7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rice P, Longden I, Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–277. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.