Abstract

Objectives

The present systematic review attempted to determine the prevalence of Linguatula serrata (L. serrata) infection among Iranian livestock. The L. serrata known as tongue worm belongs to the phylum pentastomida and lives in upper respiratory system and nasal airways of carnivores. Herbivores and other ruminants are intermediate hosts.

Methods

MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane Library were searched from Nov 1996 to 22 Apr 2019 by searching terms including “Linguatula serrata”, “linguatulosis”, “pentastomida”, “bovine”, “cattle”, “cow”, “buffalo”, “sheep”, “ovine”, “goat”, “camel”, “Iran”, and “prevalence” alone or in combination. The search was conducted in Persian databases of Magiran, Iran doc, Barakatkns (Iran medex) and Scientific Information Database (SID) with the same keywords. After reviewing the full texts of 133 published studies, 50 studies had the eligibility criteria to enter our review.

Results

By random effects model analysis, the pooled prevalence of linguatulosis was 25% (95%CI: 18.0–33.0, I2 = 98.67 % , P < 0.001) in goats; 15.0% (95%CI: 10.0–20.0, I2 = 97.95 % , P < 0.001) in sheep; 12.0% (95%CI: 7.0–18.0, I2 = 98.05 % , P < 0.001) in cattle; 7% (95%CI: 2.0–16.0, I2 = 97.52%) in buffalos and 11.0% (95%CI: 6.0–16.0%, I2 = 96.26 % , P < 0.001) in camels. The overall prevalence in livestock was estimated to be 25%. The highest infection rate was recorded in West Azerbaijan Province (68%) and the lowest rate was in Khuzestan Province (0.23%) (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

We concluded that the high prevalence of L. serrata infection in livestock (mainly ovine linguatulosis) show the endemic status of linguatulosis in several parts of Iran and will pose a risk for inhabitants. Control strategies to reduce the parasite burden among these animals are needed.

Keywords: Linguatula serrata, Linguatulosis, Prevalence, Livestock, Iran

1. Introduction

Linguatula serrata (L. serrata) is one of the cosmopolitan zoonotic food-borne parasites which belongs to class pentastomida. The shape of this parasite resembles tongue and this is the reason of calling this parasite “tongue worm”. The lifecycle of this parasite includes four stages: eggs, larvae, nymphs, and adults. The adults live in the upper respiratory system and nasal airways and frontal sinuses of the carnivores, especially dogs as final hosts. Eggs which discharge with nasopharyngeal secretions of the definitive host can be swallowed by herbivores (as intermediate hosts) such as cattle, buffalo, sheep, goat, etc. Then, the larvae hatch from the eggs and migrate mainly to mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) and other visceral organs (such as liver, lung, spleen, heart, etc.). The parasite can be transferred to the final host through consumption of meat or viscera of infected intermediate host (Soulsby, 1982; Oryan et al., 2008; Akhondzadeh Basti and Hajimohammadi, 2011; Hajipour and Tavassoli, 2019). Parasites entered in intermediate host cause pathological lesions and signs. Symptoms depend on the infected organ (Tavassoli et al., 2007a; Tavassoli et al., 2017; Shakerian et al., 2008; Dehkordi et al., 2014). Infection with this parasite causes symptoms in intermediate hosts including, emaciation, pale mucosal membranes, ascites, and serous accumulation in abdominal cavity, peritoneal inflammation, and intestinal adhesion. Important symptoms caused by the disease in sheep include: hyperplasia of pulmonary lymphatic tissue and pneumonia (Oryan et al., 2008; NourollahiFard et al., 2011). Humans can act as both intermediate and accidental final host for L. serrata and that means both larval and adult stages can infect humans (Koehsler et al., 2011). In humans, like other intermediate hosts, parasites mainly live in MLNs. But other organs such as liver, intestine, rarely brain, eye and prostate glands may also be affected (Islam et al., 2018). In some cases, migratory nymphs have recovered from anterior chamber of eye. In addition, other involvements like iritis and secondary glaucoma have been reported (Ryan and Durand, 2011). Human infection occurred via accidental ingestion of eggs passed from an infected dog or through consumption of raw/under-cooked infected viscera of contaminated sheep, goats, and cattle (Razavi et al., 2004). The most common form of human linguatulosis known as Halzoun syndrome (Marrara syndrome) is transmitted by ingestion of L. serrata nymphs (adult stage) found in intermediate host's organs and resulting in nasopharyngeal linguatulosis with signs of pharyngitis, salivation, dysphagia, and cough which all together cause type I hypersensitivity known as Halzoun syndrome. In case of visceral linguatulosis, the disease remains asymptomatic (Hajipour and Tavassoli, 2019; Shakerian et al., 2008; Meshgi and Asgarian, 2003). Detection of parasite nymphs in intermediate host is performed by biopsy, exploratory laparotomy, postmortem examination, and subsequent histopathology (Hendrix, 1998). In asymptomatic cases, there is no need for treatment as the parasite will degenerate after two years; and in symptomatic cases with high burden of parasite, surgical procedures could be useful (Hajipour and Tavassoli, 2019). It seems that visceral linguatulosis in endemic areas for L. serrata, like the Middle East region, is more than diagnosed cases (Oluwasina et al., 2014; Ravindran et al., 2008). In a study carried out in India, the prevalence of linguatulosis among examined animals was estimated to be about 18% (Sudan et al., 2014). Likewise, researchers in Bangladesh reported 19% in cattle (Ravindran et al., 2008) which reveals the equal prevalence in two neighborhood countries. Some researchers in Bangladesh reported that 50.7% of cattle and 31.0% of goats were diagnosed to be infected and they declared that human populations of the country are at high risk of linguatulosis (Islam et al., 2018). The results of a study conducted in Egypt in 2017 revealed that the total prevalence of linguatulosis was 22.8% in herbivorous animals with highest infection in goats (30%) and lowest in donkeys (8%) (Attia et al., 2017). Human cases have been detected in Asian countries including Turkey, Malaysia, China, India, and Bangladesh (Hajipour and Tavassoli, 2019). In Malaysia, the prevalence of 45.4% in adults has been reported (Prathap and Prathap, 1969). Also, such Middle East countries including Egypt, Tunisia, and Sudan have reported human infection cases (Hajipour and Tavassoli, 2019). Although some human cases have been reported from Iran, there is no clear estimation of the prevalence of the infection in Iranian population.

Numerous studies have been carried out on linguatulosis among the ruminants in Iran. Nonetheless, there is no exact estimation about the accurate load of this parasite in animals which is critical for economic burden evaluation and establishment of controlling strategies.

Based on numerous impacts of linguatulosis on the animal welfare, economy and public health, further considerations and research are deemed to be a desideratum for the epidemiological features and approaches for monitoring programs in Iran. Considering the widespread distribution of linguatulosis in Asian countries such as India and Bangladesh and trademark between countries, the importance of infection is more remarkable nowadays. As far as the researchers of this study investigated, there is no documented review about the exact prevalence of linguatulosis in livestock in Iran. Therefore, the current study is an attempt to fill out this gap.

2. Methods

-

A.

Bibliography

We performed bibliographic search according to the following topics:

Articles: Complete articles, congress summaries, and unpublished data were considered.

Type of studies: All original descriptive studies (designated as cross-sectional) about animal linguatulosis were concerned.

Epidemiological parameters of interest: Prevalence of L. serrata infection in animals was considered.

-

B.

Search strategy

The review was conducted according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane Library were searched in English language from Nov 1996 to 22 Apr 2019 for studies on linguatulosis by search terms including “Linguatula serrata”, “linguatulosis”, “pentastomida”, “bovine”, “cattle”, “cow”, “buffalo”, “sheep”, “ovine”, “goat”, “camel”, “Iran”, “epidemiology”, and “prevalence” alone or in combination. The flow diagram of the study design is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of classification of articles for inclusion in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Likewise, relevant studies were extracted from Persian databases including: Magiran, Iran doc, Barakatkns (formerly Iran medex), and Scientific Information Database (SID) with the same keywords.

-

A.

Data collection

We inclusively searched all the mentioned databases and unpublished data. The collected bibliographic references were screened carefully in order to eliminate duplicates, case reports, case series, carnivores, studies out of Iran, and human-based studies. Finally, papers with epidemiological parameters of interest were selected and 50 articles met the inclusion criteria. Those articles reporting the prevalence of linguatulosis in herbivores were included in the study (Table 1). The following data were extracted from the literature: first author, year of publication, animal's gender, prevalence rate, geographical region of study, sample size (the number of examined animals), and the year in which studies were carried out (Table 1, Table 2). References of the published data were also surveyed to extend the study and to prevent missing valuable data. Eligible data were recorded in a selection sheet (Appendix).

-

B.

Paper collection

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included studies.

| No. | Province | Total number of examined | Number of positives (%) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Khuzestan | 3958 | 9(0.23) | Saiyari et al. (1996) |

| 2 | Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari | 222 | 1(0.45) | Shekarforoush and ArzaniShahni (2001) |

| 3 | Fars | 204 | 74(36.27) | Razavi et al. (2004) |

| 4 | Fars | 200 | 29(14.5) | Shekarforoush et al. (2004) |

| 5 | East Azarbaijan | 1920 | 537(27.96) | Nematollahi et al. (2005) |

| 6 | WestAzarbaijan | 110 | 48(43.63) | Tajik et al. (2006) |

| 7 | West Azarbaijan | 200 | 105(52.5) | Tavassoli et al. (2007a) |

| 8 | WestAzarbaijan | 100 | 68(68) | Tavassoli et al. (2007b) |

| 9 | Isfahan | 400 | 102(25.5) | Shakerian et al. (2008) |

| 10 | West Azarbaijan | 80 | 15(18.75) | Tajik et al. (2008) |

| 11 | Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmar | 139 | 73(52.51) | Alborzi and Darakhshandeh (2008) |

| 12 | WestAzarbaijan | 600 | 5(0.83) | Rasouli et al. (2009) |

| 13 | East Azarbaijan | 800 | 3(0.37) | Hami et al. (2009) |

| 14 | Kerman | 407 | 263(64.61) | NourollahiFard et al. (2010a) |

| 15 | Kerman | 210 | 38(18.09) | Radfar et al. (2010) |

| 16 | West Azarbaijan | 366 | 28(7.65) | Tajik and Sabet Jalali (2010) |

| 17 | Kerman | 450 | 103(22.88) | NourollahiFard et al. (2010b) |

| 18 | East Azarbaijan | 140 | 23(16.42) | Haddadzadeh et al. (2010) |

| 19 | Mazandaran | 135 | 24(17.77) | Youssefi and Haddadzadeh Moalem (2010) |

| 20 | East Azarbaijan | 420 | 223(53.09) | Mirzaei et al. (2011) |

| 21 | West Azarbaijan | 1663 | 646(38.84) | Rezaei et al. (2011) |

| 22 | East Azarbaijan | 280 | 92(32.85) | Garedaghi (2011) |

| 23 | Tehran | 100 | 64(64) | Rajabloo et al. (2011) |

| 24 | Kerman | 808 | 132(16.33) | NourollahiFard et al. (2011) |

| 25 | West Azarbaijan | 136 | 42(30.9) | Yakhchali and Tehrani (2011) |

| 26 | Yazd | 101 | 13(12.9) | Oryan et al. (2011) |

| 27 | Mazandaran | 307 | 107(34.8) | Youssefi et al. (2012) |

| 28 | Razavi Khorasan | 400 | 73(18.25) | NourollahiFard et al. (2012) |

| 29 | Isfahan | 232 | 49(21.12) | Rezaei and Tavassoli (2012) |

| 30 | East Azarbaijan | 740 | 444(60) | Rezaei et al. (2012) |

| 31 | East Azarbaijan | 400 | 70(17.5) | Mirzaei et al. (2012) |

| 32 | East Azarbaijan | 185 | 22(11.89) | Mirzaei et al. (2013) |

| 33 | Khozestan | 223 | 37(16.6) | Alborzi et al. (2013) |

| 34 | Hamedan | 300 | 46(15.33) | Sadeghi Dehkordi et al. (2014) |

| 35 | Tehran | 799 | 258(32.3) | Bokaie et al. (2014) |

| 36 | Isfahan | 620 | 337(54.35) | Pirali Kheirabadi et al. (2014) |

| 37 | Kerman | 132 | 27(20.5) | Bamorovat et al. (2014) |

| 38 | Tehran | 774 | 198(25.58) | HasanzadehKhanbaghi et al. (2014) |

| 39 | Isfahan | 506 | 71(14.03) | PiraliKheirabadi et al. (2015) |

| 40 | East Azarbaijan | 640 | 144(22.5) | Nematollahi et al. (2015) |

| 41 | Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari | 200 | 27(13.5) | Azizi et al. (2015) |

| 42 | East Azarbaijan | 200 | 13(6.5) | Alipourazar and Garedaghi (2015) |

| 43 | Mazandaran | 50 | 20(4) | Youssefi et al. (2016) |

| 44 | Kermanshah | 1258 | 241(19.15) | Hashemnia et al. (2018) |

| 45 | Yazd | 272 | 50(18.38) | Farjanikish and Shokrani (2016) |

| 46 | Hamedan | 1080 | 163(15.09) | Gharekhani et al. (2017) |

| 47 | Mazandaran | 6249 | 568(9.08) | Tabaripour et al. (2017) |

| 48 | Razavi Khorasan | 400 | 76(19%) | Farshchi et al. (2018) |

| 49 | Tehran | 767 | 66(8.6%) | Bokaie et al. (2018) |

| 50 | West Azarbaijan | 104 | 63(60.6%) | Tavassoli et al. (2018) |

Table 2.

Pooled prevalence (95%CI) of Linguatula serrata in different provinces of Iran.

| Province | Goat | Sheep | Cattle | Buffalo | Camel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tehran | 53.0(46.0–60.0) | NES | NES | NES | NES |

| Fars | 16.0(13.0–20.0) | 7.0(4.0–9.0) | NES | NES | NES |

| East Azarbaijan | 17.0(6.0–32.0) | 22.0(11.0–36.0) | 6.0(1.0–14.0) | 1.0(0.0–2.0) | 5.0(1.0–10.0) |

| West Azarbaijan | 35.0(2.0–80.0) | 27.0(5.0–57.0) | 21.0(1.0–58.0) | 8.0(1.0–21.0) | NES |

| Kerman | 31.0(28.0–34.0) | 16.0(13.0–18.0) | 11.0(9.0–13.0) | NES | 11.0(2.0–27.0) |

| Mazandaran | 41.0(2.0–78.0) | 7.0(6.0–8.0) | 7.0(3.0–13.0) | NES | NES |

| Hamedan | 20.0(7.0–37.0) | 13.0(11.0–18.0) | NES | NES | NES |

| Isfahan | 26.0(24.0–28.0) | 6.0(5.0–8.0) | NES | NES | 14.0(4.0–29.0) |

| Kermanshah | 25.0(22.0–28.0) | NES | 13.0(11.0–15.0) | NES | NES |

| Chaharmahal and Bakh | NES | 4.0(0.0–11.0) | NES | NES | NES |

| Kohgiluyeh and Boyer | NES | 23.0(18.0–28.0) | NES | NES | NES |

| Yazd | NES | NES | NES | NES | 7.0(1.0–15.0) |

| Heterogeneity (I2, P) | 99.3%, p < 0.001 | 98.1%, p < 0.001 | 97%, p < 0.001 | 97.5%, p < 0.001 | 96.3%, p < 0.001 |

NES=No enough sample.

Three independent reviewers (R. Tabaripour, M. Keighobadi and S. HosseiniTeshnizi) screened the studies for their qualifications for inclusion in this study (Kapp index showed an agreement of 91% between four reviewers). Disagreements were resolved by M. Fakhar and A. Shokri.

-

C.

Quality of studies

The quality of meta-analysis was evaluated with STROBE checklist. A checklist including 22 items was considered for well reporting of observational studies. These items were related to the article's title, abstract, introduction, methods, results, and discussion sections. The score under 7.75 was considered a poor quality, between 7.76 and 15.5 low, between 15.6 and 23.5 moderate, and >23.6 high (Von Elm et al., 2007).

-

D.

Statistical analysis

In this meta-analysis, the number of examined and the number of positive cases were extracted from each study and then standard error (SE) was calculated using the following equation: (where n and p are the sample size and prevalence of study, respectively). Cochran's heterogeneity statistic (p < 0.1) and the I-squared index (25%: low; 50%: medium and 75%: high) were used to evaluate heterogeneity across effect sizes (ESs).

The prevalence for each study and pooled estimate of prevalence were presented in a forest plot in which we reported the results as ES with 95% confidence intervals (CI). When heterogeneity was present, we used a random effects model (DerSimonian–Laird method); otherwise we applied a fixed effects model (Mantel–Haenszel method) to estimate pooled effects size. Subgroup analysis was used to evaluate source of heterogeneity among studies. Potential publication bias was explored using Egger's test (P < 0.1 as significant). The meta-analysis was performed with the trial version of Stata MP Version 14 statistical software.

3. Results

Among all databases searched from 1996 to 2019 (~24 years), a total of 50 articles were appropriate to be included in this systematic review and meta-analysis study. All the articles were cross-sectional which had been designated to evaluate the prevalence of L. serrata in herbivores including sheep, goat, cattle, buffalo, and camel in Iran. Totally, 11,807 sheep, 14,084 goats, 8037 cattle, 2188 buffaloes and 3791 camels were examined, respectively (Table 1).

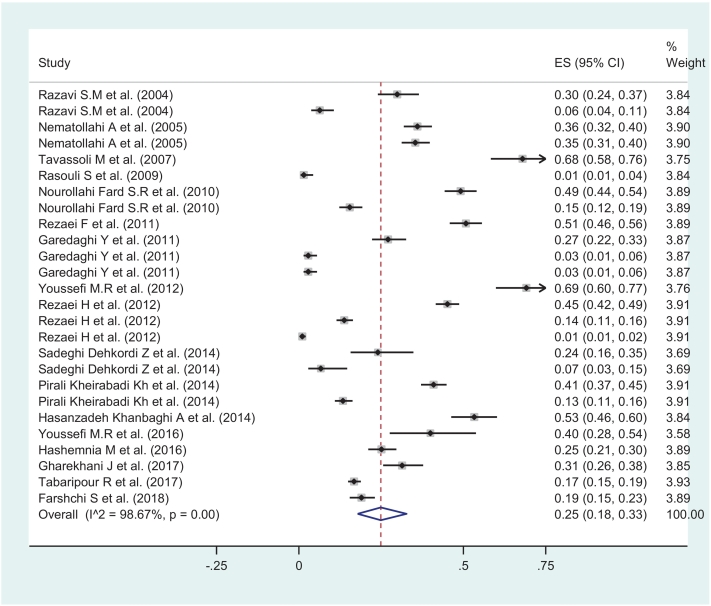

The pooled prevalence of L. serrata in goats under a random-effects model was estimated 25.0 (95%CI: 18.0–33.0, I2 = 98.67 % , P < 0.001). The pooled prevalence was significantly higher than zero (ES = 0: z = 10.77 P < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Also the pooled prevalence of L. serrata in sheep under a random-effects model was estimated 15.0 (95%CI: 10.0–20.0, I2 = 97.95 % , P < 0.001) and the pooled prevalence was significantly higher than zero (ES = 0: z = 10.36, P < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Schematic graph showing proportion meta-analysis plot of Linguatula serrata in goats in Iran (random-effects).

Fig. 3.

Schematic graph showing proportion meta-analysis plot of Linguatula serrata in sheep in Iran (random-effects).

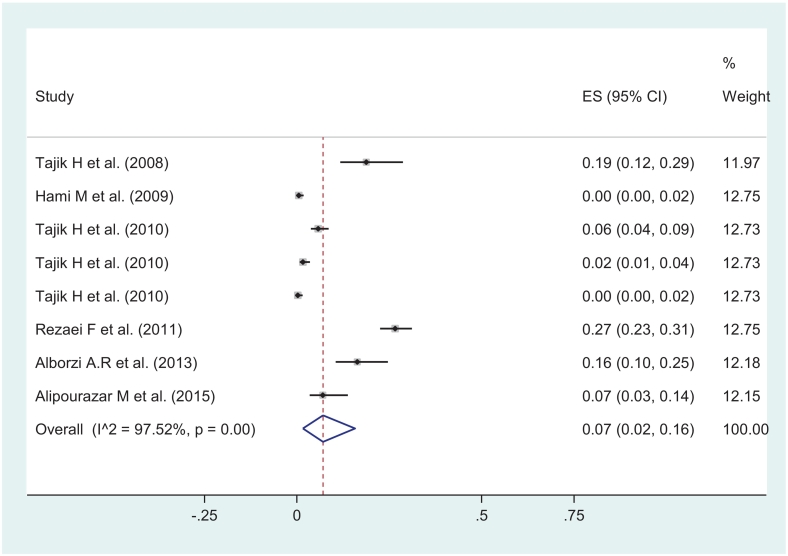

In the same way, random effect model showed the prevalence of L. serrata in cattle 12.0 (95%CI: 7.0–18.0, I2 = 98.05 % , P < 0.001) which was significantly higher than zero (ES = 0: z = 11.23 P < 0.001) (Fig. 4). The pooled prevalence of L. serrata in buffaloes was estimated 7.0% (95%CI: 2.0–16.0, I2 = 97.52 % , P < 0.001) and was significantly higher than zero (ES = 0: z = 3.41 P < 0.001) (Fig. 5). By same model, the pooled prevalence of L. serrata in camels was estimated 11.0% (95%CI: 6.0–16.0%, I2 = 96.26 % , P < 0.001) being significantly higher than zero (ES = 0: z = 3.41 P < 0.001) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 4.

Schematic graph showing proportion meta-analysis plot of Linguatula serrata in cattle in Iran (random-effects).

Fig. 5.

Schematic graph showing proportion meta-analysis plot of Linguatula serrata in buffaloes in Iran (random-effects).

Fig. 6.

Schematic graph showing proportion meta-analysis plot of Linguatula serrata in camels in Iran (random-effects).

The forest plot diagram of this review is shown in Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6. The highest infection rate was in goats (25%) and then in sheep (15%), cattle (12%), camels (11%) and the lowest infection rate was in buffaloes (7%), respectively. Most of the studies about goats belonged to Tehran Province [53.0(46.0–60.0)] and West Azerbaijan had the highest number of studies conducted on sheep [27.0(5.0–57.0)], cattle [21.0(1.0–58.0)], and buffaloes [8.0(1.0–21.0)], respectively. In addition, Kerman Province had the most records in camels [11.0(2.0–27.0)] (Table 2).

The subgroup analysis showed that the infection rate in male animals was significantly more than females (p = 0.00) except for the sheep (Table 3). Moreover, as data analysis showed, the highest prevalence of 56% was seen in mediastinal lymph nodes in goats while the maximum prevalence of 23% of mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) was seen in sheep and the lowest prevalence was about 0.01% in the liver of cattle (Table 3). There was a publication bias according the Egger's test which revealed the significant bias in the studies related to buffaloes (p = 0.009) (Table 4). This result might be due to the fewer publications about buffaloes (8 studies).

Table 3.

Pooled prevalence (95%CI) of Linguatula serrata according sex and involved organ.

| Goat | Sheep | Cattle | Buffalo | Camel | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 27.0(15.0–40.0) | 12.0(4.0–20.0) | 18.0(12.0–25.0) | NES | 16.0(8.0–24.00) |

| Female | 23.0(16.0–31.0) | 20.0(7.0–33.0) | 12.0(8.0–16.0) | 13.0(5.0–22.0) | 15.0(8.0–22) | |

| p-Value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | – | 0.091 | |

| Involved organ | Mesenteric lymph nod | 15.0(8.0–24.0) | 23.0(14.0–34.0) | 20.0(13.0–28.0) | 16.0(6.0–30.0) | 16.0(13.0–19.0) |

| Liver | 22.0(7.0–43.0) | 7.0(0.0–25.0) | 0.01(0.00–1.0) | NES | 3.0(1.0–5.0) | |

| Mediastinal lymph nodes | 52.0(48.0–56.0) | 6.0(3.0–11.0) | NES | NES | 2.0(1.0–3.0) | |

| Lung | 52.0(35.0–68.0) | NES | 4.0(1.0–7.0) | 1.0(0.0–2.0) | NES | |

| Mesenteric and Media | 17.0(15.0–19.0) | 16.0(14.0–18.0) | NES | NES | NES | |

| Spleen | NES | NES | NES | NES | NES | |

| Lymph nodes (LN) | NES | NES | NES | NES | NES | |

NES=No enough sample.

Table 4.

The results of Egger's test to assess publication bias among studies.

| Animals | Coef | Std. Err. | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Goat | 1.97 | 1.91 | 1.03 | 0.32 |

| Sheep | 2.03 | 1.19 | 1.70 | 0.11 |

| Cattle | 0.06 | 1.44 | 0.03 | 0.83 |

| Buffalo | 6.10 | 1.59 | 3.83 | 0.009 |

| Camel | 1.38 | 2.04 | 0.68 | 0.51 |

In addition, distribution of L. serrata in 13 provinces of Iran is shown in (Table 1). The highest infection rate of L. serrata in herbivores was recorded in West Azerbaijan Province (68%), then Kerman (64.61%), followed by Tehran (64%), East Azerbaijan (60%), Isfahan (54.35%), and Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmar (52.51%); meanwhile, the lowest rate belonged to Khuzestan (0.23%) with a significant difference among them (Table 1).

4. Discussion

Several studies have been carried out to determine the prevalence of L. serrata among herbivores in Iran, but there is no documented exact estimation about this subject.

As the parasite involves the ruminants, the rate of infection is high in regions with farming animal activities. The highest infection rate was reported in goats and in all provinces; Mazandaran with 69.15% infection rate had the highest rate in Iran. This may be related to the climatic condition and humidity, different forage habitats of goats, or more exposure to dogs (Hajipour and Tavassoli, 2019). Overall, Tabriz in East Azerbaijan (68%) and Urmia in West Azerbaijan (60%) had the highest prevalence rates of infection. The reason for high prevalence of infection in these regions may be related to the climatic parameters and high humidity which create optimum condition for parasite eggs survival in the environment. Also, infection with L. serrata seems to be higher in mediastinal and mesenteric regions because the mesenteric lymph nodes, located in the way of portal circulation formerly than other organs. In a study carried out by NourollahiFard in 2010, they examined mesenteric and mediastinal lymph nodes of 450 cattle at different sexes and age groups. In this study, they found that 16.22% of mesenteric lymph nodes were infected with this parasite and the infection rate was increased with age as the higher prevalence of infection was observed in animals aged above four years. Also, the prevalence of L. serrata nymphs in different seasons differed significantly (p < 0.05) and the infection rate was higher in autumn season which may be due to humidity or climatic variations (NourollahiFard et al., 2010a). Rezaei et al. (2011) studied the prevalence of L. serrata infection among dogs (definitive host) and domestic ruminants (intermediate host) in the northwestern parts of Iran. They examined upper respiratory tract of 97 dogs (45 females and 52 males) and the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) of 396 goats (203 females and 193 males), 406 buffaloes (166 females and 240 males), 421 cattle (209 females and 212 males), and 438 sheep (223 females and 215 males) for L. serrata infection. They categorized the animals into four age groups, including younger than six months, six to 24 months, two to four years, and older than four years old. Their results showed that 27.83% of dogs were infected with L. serrata. The infection rate for goats, buffaloes, cattle and sheep was 50.75%, 26.6%, 36.62% and 42.69%, respectively.

The results revealed that there was a significant correlation between prevalence rate with age and sex in all animals (P ≤ 0.05). The highest prevalence rate was found in goats (P ≤ 0.05) (Rezaei et al., 2011). In a study carried out in Urmia in 2006 by Tajik et al., the rate of 44% infection with L. serrata was reported in MLNs of examined cattle while in 2009, Yakhchali and Tehrani, 2011 reported the prevalence rate of 57% in MLNs of cattle in the same city (Tajik et al., 2006; Yakhchali and Tehrani, 2011). Furthermore, Mirzai et al. reported the prevalence rate of 17.25% infection in MLNs of cattle in Tabriz and the prevalence rate of 16.8% was reported in Ahvaz in 2013 by Alborzi et al. (Mirzaei et al., 2012; Alborzi et al., 2013). Only 8 studies are available about buffaloes' linguatulosis in Iran and the highest prevalence of 26.6% was reported from MLNs by Rezaei et al. (2011) in Urmia and the rate of 18.75% by Tajik et al. (Tajik et al., 2008; Sinclair, 1954). Sheep were the most studied herbivores in Iran and the highest rate of infection with L. serrata (52.5%) was reported in 2007 by Tavassoli et al. in Urmia (Tavassoli et al., 2007b) followed with 42.69% reported by Rezaei et al. in 2011 in the same region (Rezaei et al., 2011). The high prevalence of linguatulosis in dogs and domestic ruminants revealed that there is a high risk of this infection as an endemic disease in the northwestern region of Iran. Also, the study with serological method carried out by Yektaseresht et al. in 2017 in Fars Province revealed the seropositivity of 46.66% in sheep (Yektaseresht et al., 2017). Since this province is one of the most important foci of animal husbandry, preventive measurements and control of infection with L. serrata should be seriously considered in this province.

Prevalence studies of L. serrata from different regions in domestic animals have shown that the infection has a global distribution. The reports indicating the prevalence of 43% in Beirut (Khalil and Schacher, 1965), 72% in certain areas of Britain (Sinclair, 1954), 50.7% in Bangladesh cattle (Islam et al., 2018), 13.8% in Talca, Chile (Parraguez et al., 2017), 14.47% in Iraqi cattle (A1-Sadi and Ridha, 1994), and 25% in Egyptian camels (Khalil, 1973). These data show the wide range of infection among animals in the world.PF.

In a study carried out in 2017 in Australia by Shamsi et al., the researchers chose a number of definitive hosts for infection, including red foxes, feral cats, wild dogs, and intermediate hosts including cattle, sheep, feral pigs, rabbits, goats, and a European hare from the hilltops of south-eastern Australia for detecting L. serrata among them. Their results showed that totally 14.5% of red foxes (n = 55), 67.6% of wild dogs (n = 37), and 4.3% of cattle (n = 164) were infected. They concluded that common occurrence of the parasite in wild dogs, and less frequently in foxes, suggests that these wild canids can act as a potential reservoir for infection of livestock, wildlife, domestic dogs, and possibly humans. The high rate of linguatulosis in wild dogs and foxes in south-eastern Australia suggests that this parasite is more common than what it was previously estimated. Among all potential intermediate hosts in the area, only 4.3% of cattle were infected with parasites' nymphs which suggest that the search for the host(s) acting as the main intermediate host in the region should be continued (Shamsi et al., 2017). There is a correlation between animal husbandry and canine linguatulosis. Eating the raw offal, especially liver of farm animals, is the main source of canine infection. In the mentioned study, stray dogs were more infected than owned dogs which can be justified with better veterinary cares and feeding in the second group (Oluwasina et al., 2014).

Reports from Asian countries, and especially the Middle East region and Iran confirm that linguatulosis poses veterinary and public health importance. In addition, in the Middle East, Halzoun also occurs after consuming uncooked sheep/goats in some religious feasts. Also, a new intermediate host named crested porcupines (Hystrix indica) which consumes meat and viscera has been reported from southwest of Iran (Rajabloo et al., 2014). Several human nasopharyngeal involvement cases have been reported from Iran following the consumption of barbecued liver (Tabibian et al., 2012; Maleky, 2001; Siavashi et al., 2002; Mohammadi et al., 2008). It is believed that some unhealthy mindsets, such as the belief that eating raw liver is nutritionally more efficient, play an important role in human linguatulosis in Iran. In this regard, Montazeri et al. reported two cases of linguatulosis in the nose and mouth of a 28 year old woman and her 11 year old daughter who had a history of eating the raw gut of sheep and complained of coughing, headache, oral and nasal discharge (Montazeri et al., 1997). In addition, Sadjjadi et al. reported a case of pharyngeal linguatulosis in a 35 year old woman in Shiraz (Sadjjadi et al., 1998).

In a study carried out in Kerman by Yazdani et al., a 32-year-old woman with history of eating raw liver and complaining of upper respiratory symptoms was reported (Yazdani et al., 2014). Maleky et al. in Tehran reported a 25 year old woman with throat pentastomiasis (Maleky, 2001). Also, two cases of Halzoun syndrome were reported in 2012 from Isfahan by Tabibian et al. They reported an Afghan mother and daughter (aged 34 and 23) in Isfahan with history of eating raw goat liver (Hamid et al., 2012). Siavoshi et al. reported three cases of Halzoun syndrome including a man and two women with history of consuming raw liver (Siavoshi et al., 2002). The latest report of pharyngeal linguatulosis was released by Jahanbakhsh et al. in Kermanshah about a 34 year old man with history of consuming raw goat liver (Janbakhsh et al., 2015).

In Turkey, human infestation with L. serrata has also been reported. Yilmaz et al. reported a 26 year old woman in Van Province complaining of coughing Yilmaz et al. (2011). Also, a pentastomiasis case in a 70 year old native farmer from Keningau, Sabah, East Malaysia was reported in 2011 with a one-month history of upper abdominal discomfort, weight loss, anorexia, jaundice, and dark urine. After using the Whipple procedure and doing some histopathological examinations, the parasite was diagnosed as a nymph stage of Armillifer moniliformis (Latif et al., 2011). Overall, these results show that special attention should be paid to the public health and animal care in order to prevent the infection in Asian and African countries.

In conclusion, the high prevalence of L. serrata infection in the Iranian livestock (mainly ovine linguatulosis) shows the endemic status of linguatulosis in Iran and will pose a risk for the inhabitants. In developing countries, the main reason of getting infected among individuals with low economical income is consuming offal (and especially raw offal) such as tongue, brain, liver, kidney, intestine, and heart. Therefore, an exact inspection of visceral organs and particularly lymph nodes is needed in the slaughter houses to prevent human linguatulosis. Accordingly, people should be aware of the disadvantages and risks of eating raw / undercooked liver or other internal organs of herbivores. Meanwhile, physicians should also be aware of the illness and consider L. serrata infestation in patients with complains of upper respiratory tract symptoms in endemic areas. Altogether, our data provide some valuable information regarding the epidemiology of linguatulosis in domestic ruminants in Iran which will likely be very favorable for management and control programs of this disease. Therefore, feeding dogs with the offal of infected animals should be prevented in order to control the infection in ruminants.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

We greatly appreciate Vice Chancellors for Research and Technology of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences for funding this study (project number: 1615).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Appendix A. Article information sheet

References

- A1-Sadi H.I., Ridha A.M. Comparative pathology of the spleen and lymph nodes of apparently normal cattle, sheep and goats at the time of normal slaughter. Small Rumin. Res. 1994;14:167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Akhondzadeh Basti A., Hajimohammadi B. University of Tehran Press; 2011. Principles of Meat and Abattoir Hygiene. [Google Scholar]

- Alborzi A., Darakhshandeh T. A survey of infection of Linguatula serrata nymphs in slaughtered sheep at Yasuj abattoir. J Vet Iran. 2008;4(1):103–109. [Google Scholar]

- Alborzi A., HaddadMolayan P., Akbari M. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in mesenteric lymph nodes of cattle and buffaloes slaughtered in Ahvaz Abattoir, Iran. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2013;8(2):327–332. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alipourazar M., Garedaghi Y. Hashemzadefarhang H. Prevalence of cattle and buffalo lung-worm infestation in Tabriz city, Iran. Biol Forum. 2015;7(1):195–198. [Google Scholar]

- Attia M.M., Mahdy O.A., Saleh N.M.K. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata (order: Pentastomida) nymphs parasitizing camels and goats with experimental infestation of dogs in Egypt. Int J Adv Res Biol Sci. 2017;4(8):197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Azizi H., Nourani H., Moradi A. Infestation and pathological lesions of some lymph nodes induced by Linguatula serrata nymphs in sheep slaughtered in Sharekord area (southwest Iran) AianPac J Trop Biomed. 2015;5(7):566–570. [Google Scholar]

- Bamorovat M., BorhaniZarandi M., Mostafavi M. The prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in mesenteric and mediastinal lymph nodes in one-humped camels (Camelus dromedaries) slaughtered in Rafsanjan slaughterhouse, Iran. J. Parasit. Dis. 2014;38(4):374–377. doi: 10.1007/s12639-013-0258-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokaie S., Khanjari A., Nemati G. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata in mesenteric lymph nodes of slaughtered cattle in two slaughterhouses in Tehran. J Zoon Dis. 2014;2(1):43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bokaie S., Khanjari A., Rabiee M.H., Hajmohammadi B., Shirali S., Nemati G. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in slaughtered sheep from Tehran province, Iran. Bulg J Vet Med. 2018 [Google Scholar]

- Dehkordi Z.S., Pajohi-Alamoti M.R., Azami S., Bahonar A.R. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata in lymph nodes of small ruminants: case from Iran. Comp Clin Path. 2014;23(3):785–788. [Google Scholar]

- Farjanikish G., Shokrani H. Prevalence and morphopathological characteristics of linguatulosis in one-humped camel (Camelus dromedarius) in Yazd, Iran. Parasitol. Res. 2016;115(8):3163–3167. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-5074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farshchi S., Alikhani M.Y., Sharifi Choresh K., Khaledi A., Hoseini Farrash B.R., Sharifi Choresh K. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in goats slaughtered in Mashhad slaughterhouse, Iran. Avicenna J Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;5(3):52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Garedaghi Y. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymph in goat in Tabriz, north-west of Iran. Vet Res Forum. 2011;2:129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Gharekhani J., Esmaeilnejad B., Brahmat R., Sohrabei A. Prevalence of Linguatula serrate infection in domestic ruminants in west part of Iran: risk factors and public health implications. J Vet Med Istanbul Univ. 2017;43(1):28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Haddadzadeh H.R., Athari S.S., Abedini R. One-humped camel (Camelus dromedaries) infestation with Linguatula serrata in Tabriz, Iran. Iran J ArthropodBorne Dis. 2010;4(1):54–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajipour N., Tavassoli M. Prevalence and associated risk factors of Linguatula serrata infection in definitive and intermediate hosts in Iran and other countries: a systematic review. Vet Parasitol Region Stud Report. 2019;16:100288. doi: 10.1016/j.vprsr.2019.100288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hami M., Naddaf S.R., Mobedi I. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata infection in domestic bovids slaughtered in Tabriz Abattoir, Iran. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2009;4(3):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Hamid T., Hossein Y.D., Bahadoran-Bagh-Badorani Mehran F.S., Masood E.H. A case report of Linguatula serrata infestation from rural area of Isfahan city. Iran. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2012;42:1–3. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.100142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HasanzadehKhanbaghi A., RanjbarBahadori S., Hoghoghi Rad N. Occurrence of linguatulosis in small ruminants slaughtered in Shahryar slaughterhouse. J. Comp. Pathol. 2014;10(4):1059–1064. [Google Scholar]

- Hashemnia M., Rezaei F., Sayadpour M., Shahbazi Y. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs and pathological lesions of infected mesenteric lymph nodes among ruminants in Kermanshah, Western Iran. Bulgarian J Vet Med. 2018;21(1):94–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix C.M. Mosby Inc; 1998. Diagnostic Veterinary Parasitology; pp. 228–233. [Google Scholar]

- Islam R, Anisuz Zaman, Hossain Md S, Alam Z, Islam A, Noor Ali Khan Abu H et al. Linguatula serrata, a food-borne zoonotic parasite, in livestock in Bangladesh: some pathologic and epidemiologic aspects. Vet Parasitol Region Stud Report 2018; 13: 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Janbakhsh A., Hamzavi Y., Babaei P. The first case of human infestation with Linguatula serrata in Kermanshah Province. J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci. 2015;19:58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil G.M. Linguatula serrata from mongrel dogs in El-Dakhla Oasis (Egypt) J. Parasitol. 1973;59:288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil G.M., Schacher J.F. Linguatula serrata infection in relation to Halzoun and the marrara syndrome. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1965;14:736–746. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1965.14.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehsler M, Walocchnik J, Georgopoulos M, Pruente et al. Linguatula serrata tongue worm in human eye, Astria Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011;17(5):870–872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Latif B., Omar E., Heo C.C., Othman N., Tappe D. Human pentastomiasis caused by Armillifer moniliformis in Malaysian Borneo. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2011;85:878–881. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.11-0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleky F. A case report of Linguatula serrata in human throat from Tehran, Central Iran. Indian J. Med. Sci. 2001;55:439–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maleky F.A. Case report of Linguatula serrata in human throat from Tehran, central Iran. Indian J. Med. Sci. 2001;55(8):439–441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshgi B., Asgarian O. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata infestation in stray dogs of Shahrekord, Iran. J. Vet. Med. 2003;50(9):466–467. doi: 10.1046/j.0931-1793.2003.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei M., Asgarinezad H., Rezaeisaghinsara H. A survey of Linguatula serrata infection in sheep in Tabriz abattoir, East Azarbaijan Province. J. Vet. Med. 2011;3(1):69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei M., Azimi E., Sami M. Infection rate of Linguatula serrata nymphs in cattle slaughtered in Tabriz abattoir, Iran. Exp Anim Biol. 2012;1(1):47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mirzaei M., Rezaei H., Ashrafihelan J., Nematollahi A. The prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in one-humped camel (Camelus dromedarius) in northwest of Iran. Sci Parasitol. 2013;14(1):47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadi G.A., Mobedi I., Ariaiepour M. A case report of nasopharyngeal linguatuliasis in Tehran, Iran and characterization of the isolated Linguatula serrata. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2008;3:53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Montazeri A., Gamali R., Kazemi A. A case report of Halzoun syndrome. TUMJ. 1997;55:20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Nematollahi A., Karimi H., Niyazpour F. The survey of infection rate and histopathological lesions due to nymph of Linguatula serrata on slaughtered farm animal in East Azarbaijan slaughter houses during different seasons of year. J Fac Vet Med Univ Tehran. 2005;60(2):161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Nematollahi A., Rezaei H., AshrafiHelan J., Moghaddam N. Occurrence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in cattle slaughtered in Tabriz, Iran. J. Parasit. Dis. 2015;39(2):140–143. doi: 10.1007/s12639-013-0301-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NourollahiFard S.R., Kheirandish R., NorouziAsl E., Fathi S. The prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in mesenteric lymph nodes in cattle. Am. J. Anim. Vet. Sci. 2010;5(2):155–158. [Google Scholar]

- NourollahiFard S.R., Kheirandish R., NorouziAsl E., Fathi S. The prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in goats slaughtered in Kerman slaughterhouse, Kerman, Iran. Vet. Parasitol. 2010;171(1–2):176–178. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NourollahiFard S.R., Kheirandish R., NorouziAsl E., Fathi S. Mesenteric and mediastinal lymph node infection with Linguatula serrata nymphs in sheep slaughtered in Kerman slaughterhouse, southeast Iran. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2011;43(1):1–3. doi: 10.1007/s11250-010-9670-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NourollahiFard S.R., Ghalekhani N., Kheirandish R. The prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in camels slaughtered in Mashhad slaughterhouse, northeast, Iran. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2012;2(11):885–888. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(12)60247-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluwasina O.S., Thank God O.E., Augustine O.O., Gimba F.I. Linguatula serrata (Porocephalida: Linguatulidae) infection among client-owned dogs in Jalingo, North Eastern Nigeria: prevalence and public health implications. J Parasitol Res. 2014;2014:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2014/916120. (916120) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oryan A., Sadjjadi S., Mehrabani D., Rezaei M. The status of Linguatula serrata infection of stray dogs in Shiraz, Iran. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2008;17:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Oryan A., Khordadmehr M., Ranjbar V.R. Prevalence, biology, pathology, and public health importance of linguatulosis of camel in Iran. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2011;43(6):1225–1231. doi: 10.1007/s11250-011-9830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parraguez M., Muñoz P., Chaigneau F., Garrido C. Prevalence of bovine hepatic linguatuliasis in a slaughterhouse in Talca, Chile. RIVEP. 2017;28:169–177. [Google Scholar]

- Pirali Kheirabadi K., Fallah A., Abolghasemi A. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in slaughtered goats in Isfahan Province. Iran. J Vet Med. 2014;8(2):79–83. [Google Scholar]

- PiraliKheirabadi K., Fallah A., Azizi H.R. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in slaughtered sheeps in Isfahan province, southwest of Iran. J. Parasit. Dis. 2015;39(3):518–521. doi: 10.1007/s12639-013-0388-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prathap K, K Prathap K, Bolton J M. Pentastomiasis: a common finding at autopsy among Malaysian aborigines. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1969; 18(1):20–7. [PubMed]

- Radfar M.H., Fathi S., AsgaryNezhad H., NorouziAsl E. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in one-humped camel (Camelus dromedaries) in southeast of Iran. Sci Parasitol. 2010;11(4):199–202. [Google Scholar]

- Rajabloo M., Youssefi M.R., Majidi Rad M. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in one-humped camel (Camelus dromedarus) in Tehran, Iran. Glob Vet. 2011;6(5):438–440. [Google Scholar]

- Rajabloo M., Razavi S.M., Shayegh H., MootabiAlavi A. Nymphal linguatulosis in Indian crested porcupines (Hystrix indica) in southwest of Iran. J. Arthropod. Borne Dis. 2014;9(1):131–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasouli S., Hajimohammadi B., Athari S. Study of the infestation rate of the kidney and spleen of domestic ruminants by Linguatula serrata nymphs in Urmia slaughterhouse. Vet J Islamic Azad Univ Tabriz Branch. 2009;2(4):295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran R., Lakshmanan B., Ravishankar C., Subramanian H. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata in domestic ruminants in South India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2008;39(5):808–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razavi S.M., Shekarforoush S.S., Izadi M. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in goats in Shiraz, Iran. Small Rumin. Res. 2004;54:213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Farid Rezaei1, Mousa Tavassoli1*, Moosa Javdani. Prevalence and morphological characterizations of Linguatula serrata nymphs in camels in Isfahan Province, Iran. Vet Res Forum 2012; 3 (1) 61–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rezaei F., Tavassoli M., Mahmoudian A. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata infection among dogs (definitive host) and domestic ruminants (intermediate host) in the North West of Iran. Vet Med. 2011;56(11):561–567. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei H., Ashrafihelan J., Nematollahi A., Mostafavi E. The prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in goats slaughtered in Tabriz, Iran. J. Parasit. Dis. 2012;36(2):200–202. doi: 10.1007/s12639-012-0104-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan Edward T., Durand Marlene. Tropical Infectious Diseases. Third edition. 2011. Ectoparasites, Pentastomiasis – Chapter 124. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghi Dehkordi Z., Pajohi-Alamoti M.R., Azami S., Bahonar A.R. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata in lymph nodes of small ruminants: case from Iran. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2014;23(3):785–788. [Google Scholar]

- Sadjjadi S.M., Ardehali A., Shojaei A. Case report of Linguatula serrata in human pharynx from Shiraz, southern Iran. Med J Islam Repub Iran (MJIRI) 1998;12(2):193–194. [Google Scholar]

- Saiyari M., Mohammadian B., Sharma R.N. Linguatula serrata (Frolich 1789) nymphs in lungs of goats in Iran. Trop AnimHealthProd. 1996;28:312–314. doi: 10.1007/BF02240825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakerian A., Shekarforoush S.S., Ghafari Rad H. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymph in one-humped camel (Camelus dromedarius) in Najaf-Abad, Iran. Res. Vet. Sci. 2008;84:243–245. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamsi S., Mc Spadden K., Baker S., Jenkins D.J. Occurrence of tongue worm, Linguatula serrata (Pentastomida: Linguatulidae) in wild canids and livestock in south-eastern Australia. Int J Parasitol: Parasites and Wild Life. 2017;6:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ijppaw.2017.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekarforoush S.S., ArzaniShahni P. The study of prevalence rate of Linguatula serrata nymph in liver of sheep, goat and cattle in Shahrekord. Iran J Vet Res. 2001;2(1):57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Shekarforoush S.S., Razavi S.M., Izadi M. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in sheep in Shiraz, Iran. Small Rumin. Res. 2004;52:99–101. [Google Scholar]

- Siavashi M.R., Assmar M., Vatankhah A. Nasopharyngeal pentastomiasis (Halzoun): report of 3 cases. Iran J Med Sci. 2002;27:191–192. [Google Scholar]

- Siavoshi M., Asmar M., Vatankhah A. Nasopharyngeal pentastomiasis (Halzoun): report of 3 cases. IJMS. 2002;27:191–192. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair K.B. The incidence and life cycle of Linguatula serrate (Frolich 1789) in Great Britain. J. Comp. Pathol. 1954;64:371–383. doi: 10.1016/s0368-1742(54)80038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulsby E.J.L. vol 6. Lea and Febiger; Philadelphia: 1982. Helminths, Arthropods and Protozoa of Domesticated Animals; pp. 496–499. [Google Scholar]

- Sudan V., Jaiswal A.K., Shanker D. Infection rates of Linguatulaserrata nymphs in mesenteric lymph nodes from water buffaloes in North India. Vet. Parasitol. 2014;205:408–411. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabaripour R., Fakhar M., Alizadeh A. Prevalence and histopathological characteristics of Linguatula serrata infection among slaughtered ruminants in Mazandaran Province, northern Iran. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2017;26(6):1259–1265. [Google Scholar]

- Tabibian H, YousofiDarani H, Bahadoran-Bagh-Badorani M, et al. A case report of Linguatula serrata infestation from rural area of Isfahan city, Iran. Adv Biomed Res 2012; 1: 1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Tajik H., Sabet Jalali F.S. Linguatula serrata prevalence and morphometrical features: an abattoir survey on water buffaloes in Iran. Italy J Anim Sci. 2010;9:348–351. [Google Scholar]

- Tajik H., Tavassoli M., Dalirnaghadeh B., Danehloipour M. Mesenteric lymph nodes infection with Linguatula serrata nymphs in cattle. Iran J Vet Res Uni Shiraz. 2006;7(4):82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Tajik H., Tavassoli M., Javadi S., Baghebani H. The prevalence rate of Linguatula serrata nymphs in Iranian river buffaloes. Asian J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2008;3(3):174–178. [Google Scholar]

- Tavassoli M., Tajik H., Dalirnaghadeh B., Hariri F. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymph and gross changes of infected mesenteric lymph nodes in sheep in Urmia, Iran. Small Rumin. Res. 2007;72:73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Tavassoli M., Tajik H., Dalirnaghadeh B., Lotfi H. Investigation of mesenteric and mediastinal lymph nodes infection with Linguatula serrata in goats in Urmia slaughterhouse. J Vet Iran. 2007;3(3):85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Tavassoli M., Hobbenaghi R., Kargozari A., Rezaeia H. Infection and pathological lesions of lymph nodes induced by Linguatula serrata nymphs in one-humped camels in Iran. J Hellenic Vet Med Soc. 2017;68(4):529–534. [Google Scholar]

- Tavassoli M., Hobbenaghi R., Kargozari A., Rezaei H. Incidence of Linguatula serrata nymphs and pathological lesions of mesenteric lymph nodes in cattle from Urmia, Iran. Bulg J Vet Med. 2018;21(2):206–211. [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm E., Altman D.G., Egger M., Pocock S.J. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;20(335(7624)):806–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakhchali M., Tehrani A.A. Pathological changes in mesenteric lymph nodes infected with L. serrata nymphs in Iranian sheep. Revue Med Vet. 2011;162:396–399. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdani R., Sharifi I., Bamorovat M., Mohammadi M.A. Human linguatulosis caused by Linguatula serrata in the city of Kerman, south-eastern Iran - case report. Iran. J. Parasitol. 2014;9(2):282–285. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yektaseresht A., Asadpour M., Jafari A., Malekpour S.H. Seroprevalence of Linguatula serrata infection among sheep in Fars Province, south of Iran. J Zoon Dis. 2017;2:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz H., Cengiz Z.T., Cicek M., Dulger A.C. A nasopharyngeal human infestation caused by Linguatula serrata nymphs in Van Province: a case report. Turk Parazitol Derg. 2011;35:47–49. doi: 10.5152/tpd.2011.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssefi M.R., Haddadzadeh Moalem S.H. Prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymphs in cattle in Babol slaughterhouse, north of Iran. World J. Zool. 2010;5(3):197–199. [Google Scholar]

- Youssefi M.R., FallahOmrani V., Alizadeh A. The prevalence of Linguatula serrata nymph in mesenteric lymph nodes of domestic ruminants in Iran. World J. Zool. 2012;7(3):171–173. [Google Scholar]

- Youssefi M.R., Tabaripour R., Gerami A., FallahOmrani V. Electrophoretic pattern of Linguatula serrata larva isolated goat mesenteric lymph node. J. Parasit. Dis. 2016;40(2):292–294. doi: 10.1007/s12639-014-0497-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]