Abstract

Background:

Exposure to the Libby Amphibole (LA) asbestos-like fibers found in Libby, Montana, is associated with inflammatory responses in mice and humans, and an increased risk of developing mesothelioma, asbestosis, pleural disease, and systemic autoimmune disease. Flaxseed-derived secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG) has anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, and antioxidant properties. We have previously identified potent protective properties of SDG against crocidolite asbestos exposure modeled in mice. The current studies aimed to extend those findings by evaluating the immunomodulatory effects of synthetic SDG (LGM2605) on LA-exposed mice.

Methods:

Male and female C57BL/6 mice were given LGM2605 via gavage initiated 3 days prior to and continued for 3 days after a single intraperitoneal dose of LA fibers (200 μg) and evaluated on day 3 for inflammatory cell influx in the peritoneal cavity using flow cytometry.

Results:

LA exposure induced a significant increase (p<0.0001) in spleen weight and peritoneal influx of white blood cells, all of which were reduced with LGM2605 with similar trends among males and females. Levels of peritoneal PMN cells were significantly (p<0.0001) elevated post-LA exposure, and were significantly (p<0.0001) blunted by LGM2605. Importantly, LGM2605 significantly ameliorated the LA-induced mobilization of peritoneal B1a B cells.

Conclusions:

LGM2605 reduced LA-induced acute inflammation and WBC trafficking supporting its possible use in mitigating downstream LA fiber-associated diseases.

Keywords: asbestos, autoimmunity, inflammation, LGM2605, Libby Amphibole, secoisolariciresinol diglucoside

SUMMARY

Following acute exposure to Libby Amphibole (LA) asbestos-like fibers, synthetic secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (LGM2605), a small synthetic molecule, significantly reduced the LA-induced increase in spleen weight and peritoneal inflammation in C57BL/6 male and female mice. Our findings highlight that LGM2605 has immunomodulatory properties and may, thus, likely be a chemopreventive agent for LA-induced diseases.

1. INTRODUCTION

Libby amphibole (LA) asbestos-like fibers were a significant component of vermiculite that was mined for decades outside of Libby, Montana. Vermiculite was widely used throughout the community, leading to exposures not only among the miners and workers in related occupations, but also among residents. The material is a mixture of amphibole fibers for which the majority fall outside of the federally-regulated family of asbestos minerals, but exposure has clearly been linked to asbestos-related diseases, including mesothelioma, pulmonary carcinoma, asbestosis, and pleural disease [1–4]. In addition, LA causes inflammatory and autoimmune outcomes in rodent models [5–7] and humans [8]. Exposures are not limited to Libby, MT, but occur anywhere the vermiculite was shipped and used for home insulation and other products throughout the United States and Canada. In addition, similar asbestiform amphiboles in the soils and dusts in areas of the Southwest U.S. have been shown to have similar effects as LA [9], making the exposures environmental and on-going. The diseases associated with these exposures are generally refractory to treatment. New treatment modalities are needed to slow or arrest the progression of the severe respiratory and autoimmune outcomes of exposure to LA.

LA and crocidolite asbestos fibers both induce significant ROS following macrophage uptake and internalization [10]. We have previously identified the usefulness of LGM2605, synthetic lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (SDG), in preventing asbestos-induced cytotoxicity, inflammation, and oxidative/nitrosative stress [11, 12]. Importantly, we have shown, in a murine model of acute asbestos-induced peritoneal inflammation, a significant reduction in oxidative stress, and amelioration of inflammation and activation of inflammatory pathways by administering a diet rich in the lignan SDG [13]. We have previously evaluated the usefulness of synthetic SDG (LGM2605) in reducing oxidative stress and inflammation in asbestos-exposed, elicited murine peritoneal macrophages as an in vitro model of tissue phagocytic response to the presence of asbestos in the pleural space. LGM2605 reduced ROS generation via direct free radical scavenging and upregulation of the Nrf2/ARE pathway [11], while also inhibiting asbestos-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation [12]. Additionally, we further elucidated Nrf2/ARE induction by LGM2605 in protection from asbestos-induced cellular damage by evaluating LGM2605 in asbestos-exposed macrophages from wild-type (WT) and Nrf2 disrupted (Nrf2−/−) mice. While Nrf2 is upregulated following asbestos exposure and required for NLRP3 signaling, we found that the protective action of LGM2605 against asbestos-induced oxidative cell damage and inflammation occurs via Nrf2-dependent and independent pathways [14].

The current study afforded three opportunities to expand on the current knowledge of the potential of LGM2605 to impact health outcomes of mineral fiber exposure. First, it tested the material on the in vivo outcomes of a type of asbestos-like mineral fiber not yet evaluated in our model. Second, this study evaluated additional steps in the inflammatory/autoimmune processes that may impact health outcomes known to occur with LA exposure. Third, this study measures the efficacy of LGM2605 in male and female mice separately. We had previously developed a model of peritoneal inflammation that is particularly relevant to asbestos exposures due to the ability of the fibers to access the pleural and peritoneal cavities after exposure [15, 16], and which provides a rapid evaluation of acute in vivo events following exposure [13, 17, 18] for which the peritoneal cavity serves as a surrogate for the pleural cavity [15, 16]. The objective, therefore, was to evaluate the effects of LGM2605 on early inflammatory events previously demonstrated for LA in this model. The current study tested the hypothesis that LGM2605 would significantly reduce acute (3-day) LA-induced outcomes in our peritoneal exposure model, providing further evidence of its therapeutic potential.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Mice

All experiments with mice were approved by the Montana State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). The mice used were wild type, male and female C57BL/6 mice (Charles River, Seattle, WA, USA) maintained in the Montana State University Animal Resource Center. These mice were housed under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions with 12-hour light-dark cycle, constant temperature (22°C) and humidity (45%), and ad libitum food and water. Both male (n=40) and female C57BL/6 (n=30) mice were used at approximately 14 weeks of age.

2.2. Mineral Fibers (LA)

Libby amphibole (LA) fibers were provided by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) as a composite sample of asbestos-rich rock samples collected from multiple sites in the W.R. Grace mine outside of Libby, Montana. The LA sample was previously characterized using a suite of methods including transmission electron microscopy (TEM) with selected area electron diffraction (SAED) [19], scanning electron microscopy (SEM) with energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS), x-ray diffraction [20], and wavelength dispersive electron probe microanalysis (EPMA) [21].

Endotoxin testing of the fiber suspensions was performed using the PyroGene® Recombinant Factor C Endotoxin Detection System (Cambrex Bioscience, Walkersville, MD, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Tested samples included the sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), suspended LA (1.0 and 0.1 mg/ml) in sterile PBS, plus E. coli O111.B4 (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-spiked samples, all against a standard curve provided with the kit. Briefly, all prepared samples and standards were placed in a 96-well plate at 100 μl/well, and incubated for 10 min at 37°C. Detection working reagent was prepared and then added to all wells, and the plate was read immediately on a fluorescence plate reader (Fluorskan Ascent FL, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) at 380 excitation/440 emission. The plate was incubated for an hour at 37°C, then read again with the same settings using the Ascent Software, to allow calculation of the change in fluorescence (ΔRFU), which was then plotted against the standard curve. Endotoxin was not detected in any of the LA samples, with a detection limit of 0.01 EU/ml.

2.3. LGM2605 Treatment and LA Exposure

LGM2605 was prepared by as previously described [22]. Briefly, LGM2605 was synthesized from vanillin via secoisolariciresinol and a glucosyl donor (perbenzoyl-protected trichloroacetimidate under the influence of TMSOTf) through a concise route that involved chromatographic separation of diastereomeric diglucoside derivatives. Lyophylized samples of LGM2605 at 100 mg/vial were reconstituted with sterile water to produce the stock solution of 50 mg/ml. Oral gavages were performed daily using sterile angled gavage needles and administering 100 mg/kg mouse weight. Mice were weighed every day gavage was given, starting 3 days prior to LA exposure and continuing for 3 days after exposure. The dose of LGM2605 (100 mg/kg) has been tested using multiple routes of administration, such as intraperitoneal injection and oral gavage, and has been shown to significantly reduce inflammation and oxidative stress in murine models of septic cardiomyopathy [23] and neuroinflammation [24].

LA fibers were prepared as previously described [19]. Briefly, fibers were prepared as 1 mg/ml suspensions in sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4), and sonicated (Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT, USA) for five minutes prior to use to minimize aggregation of the fibers. LA fibers were not elutriated. The mice were exposed to LA by intraperitoneal injection using a 25-gauge needle with 200 μl, thus giving 200 μg per mouse in a single bolus.

Treatment groups were as follows:

No Treatment (CTL): Received saline gavage on the same days as LGM2605-treated animals, and received 200 μl of sterile saline via intraperitoneal injection on the same days as LA-treated animals.

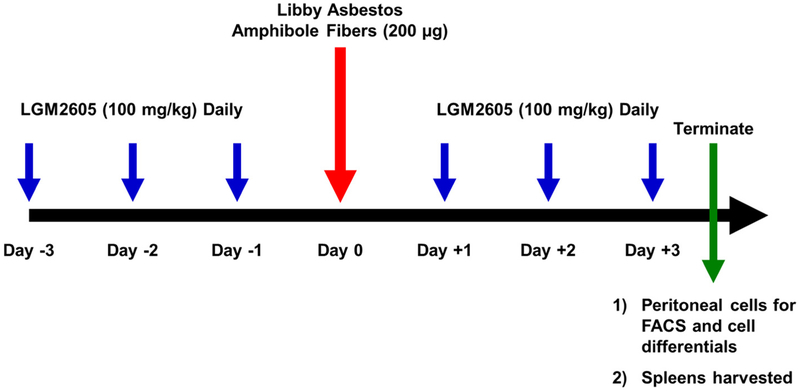

LGM2605-only (LGM2605): Received LGM2605 treatments by gavage as indicated in Figure 1, and received 200 μl of sterile saline via intraperitoneal injection on the same days as LA-treated animals.

LA-only (LA): Received saline gavage in place of LGM2605 treatments, and received LA in 200 μl of sterile saline via intraperitoneal injection as indicated in Figure 1.

Both LA and LGM2605 (LA + LGM2605): Received LGM2605 treatments by gavage and LA in sterile saline by intraperitoneal injection as indicated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Experimental Plan of LA Exposure and LGM2605 Treatment.

100 mg/kg LGM2605 (synthetic SDG) or vehicle (saline) was administered via gavage to male and female C57BL/6 (14 weeks old) mice starting 3 days prior to exposure to 200 μg LA via intraperitoneal injection and continued 3 days post-LA treatment (CTL, n=17; LGM2605, n=18; LA, n=17; and LA + LGM2605, n=18). Mice were evaluated at 3 days post-LA exposure for evidence of acute peritoneal inflammation (spleen weights, white blood cell levels, and differential white blood cell influx).

2.4. Tissues Harvested

After animal euthanasia, blood was collected by cardiac puncture into heparinized tubes (Sarstedt, Newton, NC, USA), and then centrifuged to collect plasma. Plasma was stored at −20°C until use. Peritoneal lavage (PL) was performed by first injecting five ml of sterile PBS with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) into the intact peritoneal cavity, gently agitating the peritoneal cavity, and then aspirating four ml using an 18-gauge needle. This peritoneal lavage fluid (PLF) was centrifuged, and the cells were prepared for flow cytometry (below). Spleens were also harvested. The spleens were first weighed, and then minced and prepared as single cell suspensions as previously described [25], including a brief wash in Red Blood Cell Lysis solution (eBioscience/ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to select for white blood cells. The splenocytes were counted using a Cellometer Auto T4 (Nexcelom Bioscience, Lawrence, MA, USA). Viability was shown to be greater than 90% in all cell types by Trypan blue staining.

2.5. Flow Cytometry on Peritoneal Cells

One million peritoneal cells from each sample were placed in separate tubes containing 100 μl PBS with 3% Bovine Serum Albumin as blocking agent. Sets of cells to delineate cell subsets were stained with BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA) antibodies as follows:

T cells: CD3 (FITC), Helper T cells: CD3pos(FITC), CD4pos(PE)

B cells: CD19 (PE) orlgM (PerCP Cy5.5)

B1a B cells: IgMpos (PerCP Cy5.5), CD5pos (APC), CD23neg (PE)

B suppressor cells: CD19pos (PE), CD5pos (APC), CD1dpos (FITC), CD11bpos (PerCP Cy5.5)

Polymorphonuclear cells (PMN): Ly-6G (APC)

Alpha-4 integrin: The intensity of this marker on peritoneal B1a cells indicates their readiness to traffic. Therefore, these data are expressed as median fluorescence intensity.

Cells were stained for 30 min at 4°C, and then washed with 1 ml ice cold PBS, twice. Staining was analyzed on a FACS Calibur flow cytometer using Cell Quest software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Isotype control antibodies (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) determined background staining, and less than 1% of these controls was allowed in the M1 gate for percent positive. Monocytes and lymphocytes were identified based on forward and side scatter, and then the major subsets within the lymphocyte gate were identified based on the antibodies listed above. For cell subsets, data are expressed as the frequency of cells staining positive for all markers that delineate that cell subset, as described above. Tight polygonal regions were used (instead of quadrants) to identify the ultimate subpopulations.

2.6. Statistical Analysis of the Data

The same experiment, as outlined in Figure 1, was performed 3 times with similar results. Two experiments were performed using female mice and one experiment was performed using male mice. The results show data from matching experiments of males and females. The ages and strain of the mice were the same. Results for spleen weight, total WBC counts, and cell differentials are reported as mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). All data for male and female C57BL/6 mice were first analyzed as a complete cohort (CTL, n=17; LGM2605-only, n=17; LA-only, n= 18; LA + LGM2605, n=18) using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by post-tests (Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests) analyzing significant differences among treatment groups (CTL, LGM2605-only, LA-only, and LA + LGM2605). Data were then analyzed stratified by sex (male C57BL/6 mice: CTL, n=10; LGM2605-only, n=10; LA-only, n= 10; LA+ LGM2605, n=10; or female C57BL/6 mice: CTL, n=7; LGM2605-only, n=7; LA-only, n= 8; LA + LGM2605, n=8) using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test for the main effects of sex and treatment followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons tests using GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA, www.graphpad.com. Statistically significant differences were determined at p-value of 0.05. # shown in figures indicates significant differences between unexposed (CTL) and LA-exposed (LA) groups (# = p<0.05, ## = p<0.01, ### = p<0.005 and #### = p<0.001). Asterisks shown in figures indicate significant differences between LA-exposed mice (LA) and LA-exposed mice treated with LGM2605 (LA + LGM2605) (* = p<0.05, ** = p<0.01, *** = p<0.001 and **** = p<0.0001).

3. RESULTS

In this study we demonstrated an acute inflammatory response at 3 days following exposure to 200 μg of LA fibers and evaluated the treatment effects of synthetic secoisolariciresinol diglucoside, LGM2605, on select inflammatory outcomes of LA (Figure 1).

3.1. LA-Induced Increase in Spleen Weights is Reduced by LGM2605 Treatment

Exposure to LA administered via intraperitoneal injection led to a significant increase (p<0.0001) in murine spleen weights, especially when corrected for overall mouse weight (Figure 2A). However, no significant increase (p=0.1202) in spleen weights was observed among mice exposed to LA and treated with LGM2605. Spleen weights were not significantly altered among mice treated with LGM2605-only. Spleen weights are presented as the percent of mouse body weight because the female mice were significantly smaller than the male mice.

Figure 2: LGM2605 Ameliorates the LA-Induced Increase in Spleen Weights at 3 Days Post Exposure.

Mice were treated with 100 mg/kg LGM2605 or vehicle and exposed to 200 μg LA. Spleens were harvested and weighed at 3 days post-LA exposure. Spleen weight was adjusted for mouse body weight (A). Data are also presented stratified by sex (B). All data are presented as the mean ± the standard error of the mean. # indicates a statistically significant difference (#### p< 0.0001) from CTL and asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from LA (*** p<0.001 and **** p<0.0001).

The increase in spleen weights following LA fiber exposure and the reduction associated with LGM2605 treatment was observed for both male and female C57BL/6 mice (Figure 2B). LGM2605 significantly reduced (p<0.0001) the LA-induced increase in spleen weights by 17.79% and 28.65% for male and female mice, respectively. Overall, female C67B1/6 mice displayed significantly elevated (p<0.0001) body weight-adjusted spleen weights as compared to male mice, but the pattern of LA effect and LGM2605 treatment effect was similar for both sexes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Spleen Data Summary: Mouse Weights, Spleen Weights

| Treatment Group | Females | Males | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Weight, g (SD) | Control | 19.3 (1.5) | 26.7 (1.4) | Males are significantly (p<0,05) larger |

| LGM2605 | 19.7 (1.1) | 27.6 (1.3) | ||

| LA | 18.0 (1.2) | 27.1 (1.8) | ||

| Both | 18.3 (2.4) | 26.8 (1.1) | ||

| Spleen Weight mg (SD) | Control | 92.0 (12.8) | 77.7 (8.3) | Males have larger (p<0.05) spleens |

| LGM2605 | 76.1 (14.0) | 77.2 (9.3) | ||

| LA | 122.6 (11.3) | 131.1 (10.2) | ||

| Both | 89.7 (21.7) | 105.7 (16.6) | ||

| Spleen/Body Weight (SD) | Control | 0.476 (0.068) | 0.291 (0.019) | Females have larger spleens than males per body weight |

| LGM2605 | 0.386 (0.067) | 0.279 (0.022) | ||

| LA | 0.684 (0.064) | 0.484 (0.012) | ||

| Both | 0.488 (0.088) | 0.398 (0.064) |

SD = Standard Deviation

3.2. LGM2605 Treatment Blunts Peritoneal Inflammatory Cell Influx Following LA Exposure

Following intraperitoneal exposure to 200 μg of LA fibers, white blood cell influx was significantly increased (p<0.0001) as compared to unexposed mice (Figure 3A). While mildly elevated, no significant increase (p=0.1232) in peritoneal white blood cell influx was observed among mice exposed to LA and treated with LGM2605. Compared to LA-exposed mice, mice treated with LGM2605 during LA exposure had a 44.42% reduction in LA-induced peritoneal white blood cell influx (p=0.0027). Peritoneal white blood cells were not significantly altered among mice treated with LGM2605-only.

Figure 3: LGM2605 Reduces Peritoneal WBC Levels at 3 Days Post LA-Exposure.

Mice were treated with 100 mg/kg LGM2605 or vehicle and exposed to 200 μg LA. PLF was harvested at 3 days post-LA exposure and evaluated for total WBCs (A). Data are also presented stratified by sex (B). All data are presented as the mean ± the standard error of the mean. # indicates a statistically significant difference (#### p< 0.0001) from CTL and asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from LA (** p<0.01 and **** p<0.0001).

We observed LA-induced peritoneal influx of inflammatory white blood cells was markedly (p<0.0001) higher among male C57BL/6 mice as compared to female C57BL/6 mice (Figure 3B). While white blood cell influx was significantly greater among male mice (Table 2), LGM2605 treatment led to comparable reductions for both male and female mice; LGM2605 significantly reduced (p<0.0001) the LA-induced increase in peritoneal white blood cells by 44.41% and 44.53% for male and female mice, respectively.

Table 2.

| Treatment Group | Females | Males | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total White Blood Cells (WBC) × 106 (SD) | Control | 2.03 (0.56) | 5.87 (0.65)a | Same pattern of partial protection both M and F |

| LGM2605 | 2.22 (0.69) | 5.97 (1.01)a | ||

| LA | 6.29 (1.41) | 22.46 (4.61)a | ||

| Both | 3.49 (1.10) | 12.49 (3.77)a | ||

| Lymphocytes Percent of Total WBC (SD) | Control | 22.3 (3.10) | 47.2 (5.68)a | Same pattern of partial protection both M and F |

| LGM2605 | 21.3 (1.50) | 44.8 (8.90)a | ||

| LA | 8.3 (4.21) | 11.7 (5.82) | ||

| Both | 10.6 (7.15) | 20.0 (3.16)a | ||

| Polymorphonuclear Neutrophils (Ly6G+) Percent of Total WBC (SD) | Control | 12.2 (2.00) | 1.1 (1.89)a | Same pattern of partial protection both M and F |

| LGM2605 | 8.3 (1.34) | 1.1 (0.80)a | ||

| LA | 32.9 (4.13) | 12.2 (2.39)a | ||

| Both | 20.6 (7.34) | 7.7 (1.81)a |

SD = Standard Deviation

= Comparing males to females in same treatment group, p < 0.05

3.3. LGM2605 Treatment Reduces Peritoneal PMN Levels Following LA Exposure

Exposure to LA fibers led to a significant influx (p<0.0001) of PMN cells, determined by the percentage of Ly6G-positive granulocytes (Figure 4A). Treatment with LGM2605-only did not alter the percentage of peritoneal PMN cells as compared to untreated mice. The observed increase in the percentage of PMN cells following LA exposure was significantly decreased (p<0.05) among mice treated with 100 mg/kg LGM2605 daily.

Figure 4: LGM2605 Inhibits Peritoneal PMN Cell Influx at 3 Days Post-LA Exposure.

Mice were treated with 100 mg/kg LGM2605 or vehicle and exposed to 200 μg LA. PLF was harvested at 3 days post-LA exposure and evaluated for PMN cell influx by determining the percentage of Ly6G-positive granulocytes (A). Data are also presented stratified by sex (B). All data are presented as the mean ± the standard error of the mean. # indicates a statistically significant difference (#### p<0.0001) from CTL and asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from LA (**** p<0.0001).

Compared to male C57BL/6 mice, female mice exposed to LA had significantly higher (p<0.0001) levels of peritoneal PMN cells (Table 2). However, the influx of peritoneal PMN cells observed with LA exposure and the reduction associated with LGM2605 treatment was observed for both male and female mice (Figure 4B). LGM2605 significantly reduced (p<0.0001) the LA-induced increase in PMN influx by 37.09% and 37.46% for male and female mice, respectively.

3.4. LGM2605 Treatment Alters Peritoneal WBC Subsets Following LA Exposure

The lymphocyte and macrophage composition of peritoneal WBCs was significantly altered at 3 days following LA exposure (Figure 5). Specifically, exposure to LA led to a significant decrease (p<0.0001) in the percentage of lymphocytes in the peritoneal lavage fluid (Figure 5A). Overall, LGM2605 treatment did not have a significant effect (p=0.3607) in raising the observed LA-induced decrease in peritoneal lymphocytes to baseline levels. While no significant differences in the effects of LA exposure and LGM2605 treatment were observed among female C57BL/6 mice specifically, LGM2605 treatment among male C57BL/6 mice partially protected (p=0.0220) against the LA-induced decrease in peritoneal lymphocytes (Figure 5B).

Figure 5: LGM2605 Alters Peritoneal Lymphocytes Following LA Exposure.

Mice were treated with 100 mg/kg LGM2605 or vehicle and exposed to 200 μg LA. PLF was harvested at 3 days post-LA exposure and evaluated for total lymphocytes (A). Data are also presented stratified by sex for total lymphocytes (B). All data are presented as the mean ± the standard error of the mean. # indicates a statistically significant difference (#### p< 0.0001) from CTL and asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from LA (* p<0.05).

Exposure to LA led to a significant increase (p=0.0080) in the percentage of macrophages in the peritoneal lavage fluid (Figure 6A). Peritoneal macrophages were not significantly altered among mice treated with LGM2605-only. No significant increase (p=0.9515) in peritoneal macrophage influx was observed among mice exposed to LA and treated with LGM2605 at 100 mg/kg. Compared to LA-exposed mice, mice treated with LGM2605 during LA exposure had a 20.16% reduction in LA-induced peritoneal macrophage influx. As opposed to the observed increase in peritoneal macrophages post-LA exposure among male mice, exposure to LA did not lead to a significant increase in the percentage of peritoneal macrophages among female mice (Figure 6B). Importantly, treatment with LGM2605 led to a significant decrease (p=0.0004) in the percentage of peritoneal macrophages among male C57BL/6 mice exposed to LA, which was not significantly different from unexposed, control male mice (Figure 6B).

Figure 6: LGM2605 Alters Peritoneal Macrophages Following LA Exposure.

Mice were treated with 100 mg/kg LGM2605 or vehicle and exposed to 200 μg LA. PLF was harvested at 3 days post-LA exposure and evaluated for total macrophages (A). Data are also presented stratified by sex for total macrophages (B). All data are presented as the mean ± the standard error of the mean. # indicates a statistically significant difference (## p< 0.01 and ### p< 0.001) from CTL and asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from LA (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, and *** p<0.001).

3.5. LGM2605 Treatment Does Not Alter Peritoneal B Cells, T Cells, and T Helper Cells Following LA Exposure

T and B cells are normal residents of the peritoneal cavity, including T helper cell and B1 B cell subsets [26]. Early changes in lymphocyte populations in the peritoneal cavity at this early time point would indicate inflammatory trafficking between the peritoneum, omentum and spleen [18, 26]. Overall, total peritoneal B cells and T cells were not significantly altered by LA exposure (Figures 7A and 7B), and there was no effect of the LGM2605 alone or in combination with LA. The wide distribution of data points for the B cells is due to differences between males and females, where females had a higher overall frequency of B cells than males. However, there were no significant effects of the drug in either sex. Peritoneal T helper cells were significantly decreased (p=0.0438) following LA exposure (Figure 7C), and this decrease was not apparent among mice exposed to both LA asbestos and treated with LGM2605. Treatment with LGM2605-only did not significantly alter levels of peritoneal B cells, T cells, and T helper cells.

Figure 7: LGM2605 Treatment Does Not Alter Peritoneal B Cells, T Cells, and T Helper Cells Following LA Exposure.

Mice were treated with 100 mg/kg LGM2605 or vehicle and exposed to 200 μg LA. PLF was harvested at 3 days post-LA exposure and evaluated for total B cells (A), T cells (B), and T helper cells (C). All data are presented as the mean ± the standard error of the mean. # indicates a statistically significant difference (# p< 0.05) from CTL.

3.6. LA Fiber Exposure Decreases Levels of Peritoneal B1a Cells and B Suppressor Cells

Levels of peritoneal B1a B cells were significantly (p<0.0001) decreased among mice exposed to LA fibers (Figures 8A, 8C, and 8E). Treatment with LGM2605 partially (nonsignificantly) recovered the number of peritoneal B1a B cells seen in mice treated with LA (Figure 8A). These effects were similar for both male and female mice, although recovery of B1a B cell numbers by LGM2605 was significant (p=0.0192) for female mice (Figure 8B). We feel that the observed differences in cell populations in the peritoneal cavity are not due to technical issues of recovery due to strict adherence to peritoneal wash protocols, and because of the statistical consistency within each treatment group.

Figure 8: LA Exposure Decreases Levels of Peritoneal B1a B Cells and B Suppressor Cells.

Mice were treated with 100 mg/kg LGM2605 or vehicle and exposed to 200 μg LA. PLF was harvested at 3 days post-LA exposure and evaluated for total B1a B cells (A), alpha-4 integrin levels (C), and total B suppressor cells (E). Data are also presented stratified by sex for total B1a B cells (B), alpha-4 integrin levels (D), and total B suppressor cells (F). All data are presented as the mean ± the standard error of the mean. # indicates a statistically significant difference (#### p< 0.0001) from CTL and asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from LA (* p<0.05, ** p<0.01, and *** p<0.001).

Importantly, levels of alpha-4 integrin expression on B1a B cells, an indicator for trafficking of B1a B cells [18], was significantly recovered among mice exposed to LA, plus treated with LGM2605 (Figure 8C). This pattern was evident when mice were stratified by sex, though the recovery of alpha-4 integrin expression was significant (p=0.0026) for female mice only (Figure 8D).

The observed decrease in peritoneal B suppressor cells following LA exposure was partially ameliorated by LGM2605 treatment, although not statistically significantly different (p=0.0854) (Figure 8E). Overall, levels of B1a B cells, alpha-4 integrin on B1a B cells, and B suppressor cells were not significantly altered by LGM2605 treatment-only. When stratified by sex, no significant differences in the levels of peritoneal B1a cells (p=0.0795), alpha-4 integrin expression (p=0.9271), and B suppressor cells (p=0.1464) were observed between male and female C57BL/6 mice.

In summary, LGM2605 led to at least partial recovery of the LA-induced reduction in peritoneal B1a B cells, alpha-4 integrin expression on B1a B cells, and peritoneal B suppressor cells.

4. DISCUSSION

Asbestos has several well-documented health effects leading to neoplastic, fibrotic and immune outcomes, which appear to be largely rooted in early inflammatory responses to the fibers. While the long-term outcomes are severe and refractory to treatment, it is possible that treatments could ameliorate disease by modulating steps within the early inflammatory cascade. Here, we evaluated the potential for LGM2605 to block known early inflammatory in vivo effects of intraperitoneal exposure to LA. Because asbestos fibers are known to access the pleural and peritoneal cavities after exposure [15, 16], and because collection of pleural cavity cells presents unique challenges and very few cells, we developed a peritoneal exposure model that provides rapid evaluation of in vivo events following exposure [13, 17, 18]. The peritoneal cavity has been used as a surrogate for the pleural cavity for asbestos exposure studies [15, 16]. Additionally, we examined sex-specific responses to LGM2605 treatment, given alone or in combination with LA exposure. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine such responses to LGM2605.

LGM2605, synthetic SDG, is a potent antioxidant and free radical scavenger with antiinflammatory properties. We have previously identified several key pathways through which LGM2605 is able to reduce tissue damage and inflammation [12, 13]. Acute exposure to LA in the peritoneal cavity induced inflammation, characterized by an increase in spleen weights, peritoneal WBC accumulation, and an alteration in WBC subsets within the peritoneal cavity (the site of fiber accumulation). LGM2605 significantly ameliorated peritoneal inflammation and WBC influx, specifically PMN and macrophages (especially in male mice), and partially protected against LA-induced B1a B cell trafficking. We have previously reported similar findings among Nf2+/mut mice placed on an SDG-rich diet 7 days prior to 400μg crocidolite asbestos exposure [13]. Given these outcomes, LGM2605 may be capable of reducing early inflammatory events induced by mineral fiber exposure, which are thought to contribute to the progression of several asbestos-related diseases [6, 27–29].

Increased spleen weights can indicate immune system activation and cell influx, particularly when these increases are relative to body weight, and splenomegaly is a well-documented component of chronic inflammation and rheumatic diseases in humans [30, 31]. At this early time point, activation of the adaptive immune system, with changes in major lymphocyte subsets, is unlikely, and our data support that, with no overt changes in frequency of T or B cells in the peritoneal cavity. However, we did note a relative increase in spleen weight (measured as a percentage of body weight) following exposure to LA fibers, likely due to the influx of WBCs detected in the LA-exposed mice [18]. This increase in spleen weight was reduced by LGM2605 treatment. Interestingly, the average spleen weight was elevated in female mice compared to male mice following LA treatment, though the relative effect of LGM2605 treatment reduced spleen weights to a similar degree within each sex, suggesting little sex-specific immune effects of the drug. We base our conclusions regarding cell arrival in the peritoneal cavity on published knowledge about inflammatory trafficking, in which neutrophils arrive by cytokinesis from bone marrow and lymphocytes arrive via lymphatics, often via the omentum. From a previous tracking study, we know that B1a B cells traffic from the peritoneal cavity to the spleen [18], but there are likely other sites to which they traffic, again including the omentum.

PMN and macrophage cells produce many proinflammatory and fibrotic cytokines and are mediators of oxidative stress. Upon infection or injury, these cells migrate to sites of inflammation and have been implicated in the pathogenesis of a variety of asbestos-related diseases, including mesothelioma, lung fibrosis, and autoimmunity [1–4, 8]. In this study, LGM2605 treatment blocked LA-induced recruitment of both PMN and macrophages to the peritoneal cavity. Interestingly, when examining sex-specific differences, we noted very similar patterns of the LGM2605 treatment among male and female mice, even though macrophage increases were not significant in LA exposed females (Figure 6B). However, treatment with LGM2605 still significantly reduced peritoneal macrophages in female mice exposed to LA+LGM2605 compared to fiber treatment alone, suggesting that LGM2605 is able to reduce macrophage recruitment to the site of fiber deposition.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine sex-specific responses to LA or LA+LGM2605. Some previous studies have examined human population-level data comparing types of fiber exposures or disease prevalence; while exposure type differs between sexes (mostly male occupational exposures compared to mixed female and male environmental exposures) the world-wide asbestos-associated disease incidence, progression, and life-expectancy vary little between exposed males and females [32, 33]. Our previous work utilized mostly female mice, though disease patterns are consistent between LA-exposed males and females [9]. Based on population-level data, we did not expect, and did not observe, drastic differences between female and male mice in this study. In general, immune responses to LA followed similar patterns for male and female mice, though the absolute values differed, suggesting similar responses to fibers. Because the male and female mice of this study were separate experiments, differences in the magnitude and absolute values are expected. What is important in these results are the response patterns showing the effects of LGM2605 occurring in both males and females. While additional studies are needed to determine the extent and timing of this observed response, these data do suggest that future studies should be designed with potential gender differences in mind.

The exact mechanism of LGM2605-reduced PMN and macrophage recruitment was not examined within this study, but it may be related the ability of drug to reduce local ROS/RNS and to block inflammasome activation, mechanisms previously described [11, 12]. Specifically, asbestos exposure was shown to cause oxidative stress in exposed macrophages, stress that was alleviated with LGM2605 treatment [11]. Reduction of local free radicals would reduce local tissue damage, which may then reduce inflammatory responses and immune cell recruitment. Additionally, LGM2605 was also shown to block the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages [12]. Inflammasome activation results in release of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1-beta and IL-18, which then contribute to innate cell recruitment and activation. Therefore, LGM2605 treatment may reduce innate immune cell influx by limiting early inflammatory events at the site of tissue injury by asbestos and asbestos-like fiber deposition, which may in turn have significant protective properties against development of LA-induced diseases.

As expected, we did not observe any significant changes in lymphocyte subset frequencies in the peritoneal cavity following LA exposure. We did note a slight decrease in T-helper cell percentages following LA exposure, a decrease that was ameliorated by LGM2605 treatment, but this change was less dramatic than those observed for innate immune cells. These data likely reflect the timing of the study more than responses to LA or LGM2605; 3 days is not long enough to see major changes in adaptive immune responses other than trafficking. However, it would be of interest to examine the effects of LGM2605 on adaptive immune cell response to LA and on long-term disease pathology in future studies.

While overall B cell levels were not significantly altered by LA exposure, we did see significant differences in both B suppressor and B1a cell subsets following fiber instillation and LGM2605 treatment. B suppressor cells, also known as B regulatory cells, were significantly decreased following LA exposures, consistent with previous studies [18]. These cells reduce proinflammatory cytokine production and suppress activation of CD4+ T cells and macrophages [34]. It is possible that LA-induced reduction of B suppressor cells contributes to an inflammatory environment, which then promotes progression of LA-associated pathologies, including fibrosis and autoimmunity. Treatment with LGM2605 did partially prevent LA-induced B suppressor reductions (in both male and female animals), suggesting that this drug may help to alleviate immune activity associated with mineral fiber exposures.

In both mice and humans, B1a B cells are a subset of B cells that have been implicated in autoimmunity due to their reactivity to self-antigen and their expanded numbers in autoimmune mice and humans [35–40]. B1a B cells are long-lived, self-renewing lymphocytes found primarily in the peritoneal and pleural cavities, and are major producers of IgM ‘natural autoantibodies’. Evidence of a role in autoimmunity includes studies validating that their elimination results in amelioration of disease in mouse models of lupus and diabetes [41, 42]. Upon activation, B1a cells traffic to sites of inflammation, the omentum, or the spleen where they can produce large amounts of autoantibodies. Therefore, treatments that reduce trafficking of B1a B cells may also have profound impacts on health outcomes.

Alpha-4 integrin controls B cell retention in the peritoneum [43, 44], with a decrease in expression on B1a B cells indicating that these cells are detaching from the peritoneal cavity and becoming more motile. We have previously shown that exposure to LA causes activation of peritoneal B1a B cells with a loss of alpha-4 integrin expression and trafficking to the spleen [18]. The current study demonstrated that LA exposure led to decreased alpha-4 integrin as expected. Additionally, the levels of B1a B cells measured in the peritoneal cavity 3 days post-LA exposure were significantly decreased compared to controls. Taken together, these data suggest that LA triggered B1a B cells trafficking, which is consistent with previous data [18]. Treatment with LGM2605+LA resulted a significant rescue of alpha-4 integrin expression, suggesting an ability of LGM2605 to inhibit B1a B cell trafficking. Although B1a B cell levels were still reduced within the peritoneal cavity with LGM2605+LA compared to control, they remained higher than LA-alone. Even though LGM2605 treatment did not fully retain B1a B cells in the peritoneum, it did seem to impact readiness to traffic by maintaining alpha-4 integrin expression on the B1a B cells. This suggests that the LGM2605 caused a change in the timing of events, with possibly a rapid recovery of alpha-4 integrin expression that did not completely prevent trafficking. Since B1a B cells may play a role in autoantibody production, antigen presentation, and modulation of immune responses, these results suggest that LGM2605 may have health protective properties against long-term autoimmune outcomes of LA exposure. Further studies are needed to test this hypothesis, though this would be a significant advancement for diseases that currently have little effective treatment options and no preventative strategies.

5. CONCLUSION

In summary, treatment with LGM2605 led to significant reductions in the effects of LA exposure. Specifically, LGM2605 has a significant protective (anti-inflammatory) effect on LA-induced peritoneal inflammatory cell population changes in both male and female C57BL/6 mice.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Libby Amphibole (LA)-induced diseases are linked to early inflammatory events.

We demonstrate that LGM2605 significantly reduces LA-induced splenomegaly.

LGM2605 reduces LA-induced peritoneal influx of white blood cells (WBCs).

LGM2605 specifically reduces WBC subtypes associated with autoimmune responses.

LGM2605’s immunomodulatory properties may be linked to potential chemoprevention.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND FUNDING

This work was funded in part by: NIH-R01 CA133470 (MCS), NIH-1R21CA178654-01 (MCS), NIH-1R21NS087406-01 (MCS), NIH-R03 CA180548 (MCS), 1P42ES023720-01 (MCS) and by pilot project support from 1P30 ES013508-02 awarded to MCS (its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS, NIH).

ABBREVIATIONS

- CTL

control

- ED

enterodiol

- EDS

energy dispersive spectroscopy

- EL

enterolactone

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays

- EPA

United States Environmental Protection Agency

- EPMA

electron probe microanalysis

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- LA

Libby Amphibole

- LC/MS/MS

liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry

- LGM2605

synthetic secoisolariciresinol diglucoside

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PLF

peritoneal lavage fluid

- PMN

polymorphonuclear cell

- RFU

relative fluorescence unit

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- SAED

selected area electron diffraction

- SDG

secoisolariciresinol diglucoside

- SEM

scanning electron microscopy

- SPF

specific pathogen free

- TEM

transmission electron microscopy

- WBC

white blood cell

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Melpo Christofidou-Solomidou (MCS) reports grants from the NIH and NASA during the conduct of the study. In addition, MCS has patents No. PCT/US2015/033501, No. PCT/US2016/049780, No. PCT/US17/35960, No. PCT/US2014/041636, and No. PCT/US15/22501 pending and has a founders equity position in LignaMed, LLC. MCS, RAP, KP, and SMA report grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) during the conduct of the study. KMS, DEK, and JCP have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- [1].Larson TC, Lewin M, Gottschall EB, Antao VC, Kapil V, Rose CS, Associations between radiographic findings and spirometry in a community exposed to Libby amphibole, Occup Environ Med, 69 (2012) 361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Miller A, Szeinuk J, Noonan CW, Henschke CI, Pfau J, Black B, Yankelevitz DF, Liang M, Liu Y, Yip R, McNew T, Linker L, Flores R, Libby Amphibole Disease: Pulmonary Function and CT Abnormalities in Vermiculite Miners, J Occup Environ Med, 60 (2018) 167–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Whitehouse AC, Black CB, Heppe MS, Ruckdeschel J, Levin SM, Environmental exposure to Libby Asbestos and mesotheliomas, Am J Ind Med, 51 (2008) 877–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Szeinuk J, Noonan CW, Henschke CI, Pfau J, Black B, Miller A, Yankelevitz DF, Liang M, Liu Y, Yip R, Linker L, McNew T, Flores RM, Pulmonary abnormalities as a result of exposure to Libby amphibole during childhood and adolescence-The Pre-Adult Latency Study (PALS), Am J Ind Med, 60 (2017) 20–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ferro A, Zebedeo CN, Davis C, Ng KW, Pfau JC, Amphibole, but not chrysotile, asbestos induces anti-nuclear autoantibodies and IL-17 in C57BL/6 mice, Journal of immunotoxicology, 11 (2013) 283–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kodavanti UP, Andrews D, Schladweiler MC, Gavett SH, Dodd DE, Cyphert JM, Early and delayed effects of naturally occurring asbestos on serum biomarkers of inflammation and metabolism, J Toxicol Environ Health A, 77 (2014) 1024–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pfau JC, Sentissi JJ, Li S, Calderon-Garciduenas L, Brown JM, Blake DJ, Asbestosinduced autoimmunity in C57BL/6 mice, Journal of immunotoxicology, 5 (2008) 129–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Diegel R, Black B, Pfau JC, McNew T, Noonan C, Flores R, Case series: rheumatological manifestations attributed to exposure to Libby Asbestiform Amphiboles, J Toxicol Environ Health A, 81 (2018) 734–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pfau JC, Buck B, Metcalf RV, Kaupish Z, Stair C, Rodriguez M, Keil DE, Comparative health effects in mice of Libby amphibole asbestos and a fibrous amphibole from Arizona, Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 334 (2017) 24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Blake DJ, Bolin CM, Cox DP, Cardozo-Pelaez F, Pfau JC, Internalization of Libby amphibole asbestos and induction of oxidative stress in murine macrophages, Toxicol Sci, 99 (2007) 277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pietrofesa RA, Velalopoulou A, Albelda SM, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Asbestos Induces Oxidative Stress and Activation of Nrf2 Signaling in Murine Macrophages: Chemopreventive Role of the Synthetic Lignan Secoisolariciresinol Diglucoside (LGM2605), Int J Mol Sci, 17 (2016) 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Pietrofesa RA, Woodruff P, Hwang WT, Patel P, Chatterjee S, Albelda SM, Christofidou-Solomidou M, The Synthetic Lignan Secoisolariciresinol Diglucoside Prevents Asbestos-Induced NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation in Murine Macrophages, Oxid Med Cell Longev, 2017 (2017) 7395238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Pietrofesa RA, Velalopoulou A, Arguiri E, Menges CW, Testa JR, Hwang WT, Albelda SM, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Flaxseed lignans enriched in secoisolariciresinol diglucoside prevent acute asbestos-induced peritoneal inflammation in mice, Carcinogenesis, 37 (2016) 177–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pietrofesa RA, Chatterjee S, Park K, Arguiri E, Albelda SM, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Synthetic Lignan Secoisolariciresinol Diglucoside (LGM2605) Reduces Asbestos-Induced Cytotoxicity in an Nrf2-Dependent and -Independent Manner, Antioxidants (Basel), 7 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Branchaud RM, Garant LJ, Kane AB, Pathogenesis of mesothelial reactions to asbestos fibers. Monocyte recruitment and macrophage activation, Pathobiology : journal of immunopathology, molecular and cellular biology, 61 (1993) 154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Moalli PA, MacDonald JL, Goodglick LA, Kane AB, Acute injury and regeneration of the mesothelium in response to asbestos fibers, The American journal of pathology, 128 (1987) 426–445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gilmer J, Serve K, Davis C, Anthony M, Hanson R, Harding T, Pfau JC, Libby Amphibole Induced Mesothelial Cell Autoantibodies Promote Collagen Deposition in Mice, American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology, 310 (2016) L1071–L1077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pfau JC, Hurley K, Peterson C, Coker L, Fowers C, Marcum R, Activation and trafficking of peritoneal B1a B-cells in response to amphibole asbestos, Journal of immunotoxicology, 11 (2014) 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Duncan KE, Cook PM, Gavett SH, Dailey LA, Mahoney RK, Ghio AJ, Roggli VL, Devlin RB, In vitro determinants of asbestos fiber toxicity: effect on the relative toxicity of Libby amphibole in primary human airway epithelial cells, Particle and fibre toxicology, 11 (2014) 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lowers HA, Wilson SA, Hoefen TM, Benzel WM, Meeker GP, Preparation and characterization of “Libby amphibole” toxicological testing material, [http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1012/report/OF12-1012.pdf] (2012).

- [21].Meeker GP, Bern AM, Brownfield IK, Lowers HA, Sutley SJ, Hoefen TM, Vance JS, The Composition and Morphology of Amphiboles from the Rainy Creek Complex, Near Libby, Montana, American Mineralogist, 88 (2003) 1955–1969. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Mishra OP, Simmons N, Tyagi S, Pietrofesa R, Shuvaev VV, Valiulin RA, Heretsch P, Nicolaou KC, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Synthesis and antioxidant evaluation of (S,S)- and (R,R)-secoisolariciresinol diglucosides (SDGs), Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 23 (2013) 5325–5328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kokkinaki D, Hoffman M, Kalliora C, Kyriazis ID, Maning J, Lucchese AM, Shanmughapriya S, Tomar D, Park JY, Wang H, Yang XF, Madesh M, Lymperopoulos A, Koch WJ, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Drosatos K, Chemically synthesized Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside (LGM2605) improves mitochondrial function in cardiac myocytes and alleviates septic cardiomyopathy, J Mol Cell Cardiol, 127 (2019) 232–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rom S, Zuluaga-Ramirez V, Reichenbach NL, Erickson MA, Winfield M, Gajghate S, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Jordan-Sciutto KL, Persidsky Y, Secoisolariciresinol diglucoside is a blood-brain barrier protective and anti-inflammatory agent: implications for neuroinflammation, J Neuroinflammation, 15 (2018) 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ferro A, Zebedeo CN, Davis C, Ng KW, Pfau JC, Amphibole, but not chrysotile, asbestos induces anti-nuclear autoantibodies and IL-17 in C57BL/6 mice, Journal of immunotoxicology, 11 (2014) 283–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Meza-Perez S, Randall TD, Immunological Functions of the Omentum, Trends Immunol, 38 (2017) 526–536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Padilla-Carlin DJ, Schladweiler MC, Shannahan JH, Kodavanti UP, Nyska A, Burgoon LD, Gavett SH, Pulmonary inflammatory and fibrotic responses in Fischer 344 rats afterintratracheal instillation exposure to Libby amphibole, J Toxicol Environ Health A, 74 (2011) 1111–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Cyphert JM, Carlin DJ, Nyska A, Schladweiler MC, Ledbetter AD, Shannahan JH, Kodavanti UP, Gavett SH, Comparative long-term toxicity of Libby amphibole and amosite asbestos in rats after single or multiple intratracheal exposures, J Toxicol Environ Health A, 78 (2015) 151–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gavett SH, Parkinson CU, Willson GA, Wood CE, Jarabek AM, Roberts KC, Kodavanti UP, Dodd DE, Persistent effects of Libby amphibole and amosite asbestos following subchronic inhalation in rats, Particle and fibre toxicology, 13 (2016) 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Fishman D, Isenberg DA, Splenic involvement in rheumatic diseases, Semin Arthritis Rheum, 27 (1997) 141–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Han J, Li N, Wang J, Zhou J, Zhang J, Life-threatening spontaneous splenic rupture with systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and literature review, Clin Rheumatol, 31 (2012) 1019–1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hyland RA, Ware S, Johnson AR, Yates DH, Incidence trends and gender differences in malignant mesothelioma in New South Wales, Australia, Scand J Work Environ Health, 33 (2007) 286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Burdorf A, Jarvholm B, Siesling S, Asbestos exposure and differences in occurrence of peritoneal mesothelioma between men and women across countries, Occup Environ Med, 64 (2007) 839–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Tedder TF, B10 cells: a functionally defined regulatory B cell subset, J Immunol, 194 (2015) 1395–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Mohan C, Morel L, Yang P, Wakeland EK, Accumulation of splenic B1a cells with potent antigen-presenting capability in NZM2410 lupus-prone mice, Arthritis Rheum, 41 (1998) 1652–1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Potula HH, Xu Z, Zeumer L, Sang A, Croker BP, Morel L, Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor Cdkn2c deficiency promotes B1a cell expansion and autoimmunity in a mouse model of lupus, J Immunol, 189 (2012) 2931–2940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Deng J, Wang X, Chen Q, Sun X, Xiao F, Ko KH, Zhang M, Lu L, B1a cells play a pathogenic role in the development of autoimmune arthritis, Oncotarget, 7 (2016) 19299–19311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Duan B, Morel L, Role of B-1a cells in autoimmunity, Autoimmun Rev, 5 (2006) 403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Miles K, Simpson J, Brown S, Cowan G, Gray D, Gray M, Immune Tolerance to Apoptotic Self Is Mediated Primarily by Regulatory B1a Cells, Frontiers in immunology, 8 (2017) 1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Xu Z, Duan B, Croker BP, Wakeland EK, Morel L, Genetic dissection of the murine lupus susceptibility locus Sle2: contributions to increased peritoneal B-1a cells and lupus nephritis map to different loci, J Immunol, 175 (2005) 936–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Murakami M, Yoshioka H, Shirai T, Tsubata T, Honjo T, Prevention of autoimmune symptoms in autoimmune-prone mice by elimination of B-1 cells, Int Immunol, 7 (1995) 877–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kendall PL, Woodward EJ, Hulbert C, Thomas JW, Peritoneal B cells govern the outcome of diabetes in non-obese diabetic mice, Eur J Immunol, 34 (2004) 2387–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ha SA, Tsuji M, Suzuki K, Meek B, Yasuda N, Kaisho T, Fagarasan S, Regulation of B1 cell migration by signals through Toll-like receptors, J Exp Med, 203 (2006) 2541–2550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Berberich S, Dahne S, Schippers A, Peters T, Muller W, Kremmer E, Forster R, Pabst O, Differential molecular and anatomical basis for B cell migration into the peritoneal cavity and omental milky spots, J Immunol, 180 (2008) 2196–2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]