This observational study estimates trends in US infant and youth mortality rates from 1999 to 2015 by age group and race/ethnicity compared with Canada and England/Wales.

Key Points

Question

How have infant and youth mortality trends changed in the United States between 1999 to 2015 by age, race/ethnicity, and cause of death?

Findings

All-cause mortality rates decreased in most age and racial/ethnic groups, and declines occurred for major causes of death including sudden infant death syndrome in infants and homicide and unintentional injury deaths in youth. In contrast, mortality rates from suffocation and strangulation in bed in infants and suicide and drug poisonings in youth increased over time.

Meaning

Resources should be allocated toward the prevention of suicide and drug poisoning in youth, and safe sleep techniques should be reinforced for infants.

Abstract

Importance

The United States has higher infant and youth mortality rates than other high-income countries, with striking disparities by racial/ethnic group. Understanding changing trends by age and race/ethnicity for leading causes of death is imperative for focused intervention.

Objective

To estimate trends in US infant and youth mortality rates from 1999 to 2015 by age group and race/ethnicity, identify leading causes of death, and compare mortality rates with Canada and England/Wales.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This descriptive study analyzed death certificate data from the US National Center for Health Statistics, Statistics Canada, and the UK Office of National Statistics for all deaths among individuals younger than 25 years. The study took place from January 1, 1999, to December 31, 2015, and analyses started in September 2017.

Exposures

Race/ethnicity.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Average annual percent changes in mortality rates from 1999 to 2015 and absolute rate change between 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015 for each age group, race/ethnicity, and cause of death.

Results

Among individuals from birth to age 24 years, 1 169 537 deaths occurred in the United States, 80 540 in Canada, and 121 183 in England/Wales from 1999 to 2015. In the United States, 64% of deaths occurred in male individuals and 52.6% occurred in white individuals (25.1% deaths occurred in black individuals and 17.9% in Latino individuals). All-cause mortality declined for all age groups (infants younger than 1 year [38.5% of deaths], children aged 1-9 years [10.6%], early adolescents aged 10-14 years [5%], late adolescents aged 15-19 years [17.7%], and young adults aged 20-24 years [28.1%]) in the United States, Canada, and England/Wales from 1999 to 2015. However, rates were highest in the United States. Within the United States, annual declines in all-cause mortality rates occurred among all age groups of black, Latino, and white individuals, except for white individuals aged 20 to 24 years, whose rates remained stable. Mortality rates declined across most major causes of death from 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015, with notable declines observed for sudden infant death syndrome, unintentional injury death, and homicides. Among infants, unintentional suffocation and strangulation in bed increased (difference between 2012-2015 and 1999-2002 range, 6.11-29.03 per 100 000). Further, suicide rates among Latino and white individuals aged 10 to 24 years (range, 0.21-2.63 per 100 000) and black individuals aged 10 to 19 years (range, 0.10-0.45 per 100 000) increased, as did unintentional injury deaths in white young adults (0.79 per 100 000). The rise in unintentional injury deaths is attributed to increases in drug poisonings and was also observed in black and Latino young adults.

Conclusions and Relevance

Mortality rates in the United States have generally declined for infants and youths from 1999 to 2015 owing to reductions in sudden infant death syndrome, unintentional injury death, and homicides. However, US mortality rates remain higher than Canada and England/Wales, with particularly elevated rates among black and American Indian/Alaskan Native youth. Further, there is a concerning increase in suicide and drug poisoning death rates among US adolescents and young adults.

Introduction

Since the 1960s, infant (younger than 1 year) and youth (age 1 to 24 years) mortality rates have declined worldwide.1,2 In the early 20th century, childhood deaths accounted for one-third of all deaths in the United States compared with less than 2% in 2015.3,4 Infant and youth mortality rates in the United States are notably higher than other high-income countries, despite having the highest health expenditures per capita in the world.2,5,6,7 There are also pronounced racial/ethnic disparities within the United States.8,9 In 2015, black infants were 2.3-times more likely to die than white infants.3,10 Similarly, mortality rates among black adolescents and young adults were 50% higher than rates for their white counterparts, primarily owing to higher rates of homicide.3 Recently, mortality rates due to drug poisonings and suicides have increased among adolescents and young adults in the United States,11,12 although it is unclear whether rates have increased equally across races/ethnicities and how these increases have influenced overall trends in mortality rates.

Detailed understanding of mortality trends in infants and youth are essential to understand where progress has been made and to target future public health efforts. Previous studies that have focused on mortality trends among US youth have not comprehensively examined differences by race/ethnicity, age group, and cause of death.13,14 The current study provides a detailed characterization of trends in infant and youth mortality between 1999 to 2015 by age group and race/ethnicity, identifies leading causes of death contributing to these trends, and compares mortality rates with Canada and England/Wales.2,15 Understanding changing trends in infant and youth mortality will provide insight regarding which causes of death and demographic groups should be priorities for interventions.

Methods

Institutional review board approval and patient consent were not needed because publicly available data were used. Mortality and population data from the United States were obtained from death certificates from the US National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the US Census Bureau, respectively. Mortality and population data from Canada and England/Wales were obtained from Statistics Canada and the UK Office for National Statistics, respectively.16,17 Canada and England/Wales were selected owing to basic similarities with the United States, including advanced economies, modern health care systems, and primarily white populations that are progressively becoming more diverse via immigration. Causes of death were coded with the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, and categorized with Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results death recode variables for individuals aged 1 to 24 years and with the US National Center for Health Statistics 130 Selected Causes of Infant Death. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results recodes individual International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems codes into groups for consistent analysis over time (https://seer.cancer.gov/codrecode/index.html). Race/ethnicity of each decedent was also ascertained from death certificates and classified as Asian and Pacific Islander (API), American Indian/Alaskan Native (AI/AN), non-Hispanic black or African American (black), Hispanic or Latino (Latino), and non-Hispanic white (white). Analyses for AI/AN were restricted to counties in Contract Health Services Delivery Areas to increase the sensitivity of AI/AN classification on death certificates.18

All-cause mortality rates were estimated by age group (<1, 1-4, 5-9, 10-14, 15-19, and 20-24 years) for the United States, Canada, and England/Wales from 1999 to 2015. Mortality rates for each age group in the United States were further stratified by race/ethnicity. Individuals aged 1 to 4 years and 5 to 9 years had similar leading causes of death and trends and were therefore collapsed for the US analyses to increase sample size and age-standardized in 5-year age groups to the 2000 US population.

We used the Joinpoint Regression Program (version 4.5.0., SEER*Stat) to estimate the average annual percent changes (AAPCs) in all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates from 1999 to 2015. Average annual percent changes were estimated by age group in the United States, Canada, and England/Wales and by race/ethnicity and cause of death in the United States.

To identify specific causes of death driving changes in age-specific mortality rates, we estimated the absolute difference in all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates between 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015 for the 5 leading causes of death by age and race/ethnicity for black, Latino, and white individuals. Individuals in the API and AI/AN groups were excluded from cause-specific analyses owing to sparsity of data. We further stratified causes of death observed to be increasing into more specific subgroups (eTable 1 in Supplement 1).

For total mortality and causes of death in which mortality rates increased over time, excess deaths were estimated by subtracting the observed number of deaths from the number of deaths expected if rates remained constant. The expected number of deaths were calculated by applying 1999 to 2002 age-specific mortality rates to the 2015 population. This approach conservatively estimates the number of excess deaths, as ideally rates would decline, not remain stable, over time.

Results

All-Cause Mortality Rates in the United States, Canada, and England/Wales

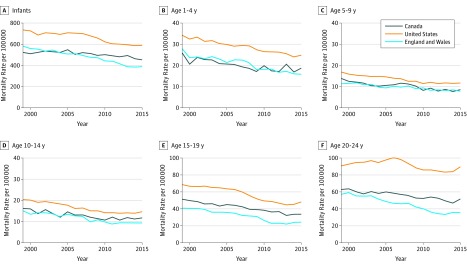

In the United States, Canada, and England/Wales, mortality rates decreased in all age groups from 1999 to 2015 (AAPCs, −0.82% per year to −4.01% per year; all P < .05) (Figure 1). However, the United States had higher mortality rates compared with Canada and England/Wales for all age groups across the time period. Differences between mortality rates in the United States and Canada narrowed over time for all age groups except individuals aged 5 to 9 years and 20 to 24 years, for whom rates diverged (Figure 1). In contrast, differences between mortality rates in the United States and England/Wales widened for all age groups over time owing to rates declining more rapidly in England/Wales than the United States. For example, mortality rates among young adults in England/Wales declined by 3.69% per year (95% CI, −4.2 to −3.2) but only by 0.82% per year (95% CI, −1.3 to −0.3) in the United States (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). The greatest disparity observed was in 2015 for individuals aged 20 to 24 years, where the mortality rate was 2.5-times higher in the United States than in England/Wales (89.5 vs 35.5 per 100 000) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. All-Cause Mortality Rates Between 1999 to 2015 for the United States, Canada, and England/Wales by Age Group.

US All-Cause Mortality Rate by Race/Ethnicity

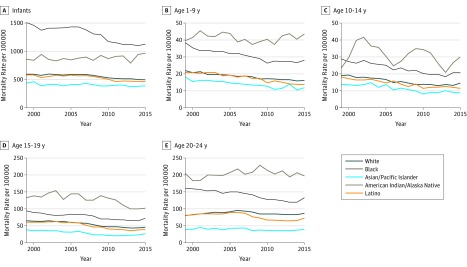

In the United States, black infants had the highest all-cause mortality rate (1128/100 000) compared with all other races/ethnicities (AI/AN, 968/100 000; white, 498/100 000; Latino, 466/100 000; API, 390/100 000) (Figure 2). In all other age groups, AI/ANs had the highest mortality rates, and APIs had the lowest. Of note, only APIs had mortality rates that were lower than Canada and comparable with England/Wales in 2015 (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Mortality rates in all other US races/ethnicities were notably higher (eTable 3 in Supplement 1).

Figure 2. All-Cause Mortality Rates Between 1999 and 2015 in the United States by Age Group and Race/Ethnicity .

From 1999 to 2015, API, black, and Latino individuals had significant annual declines in all-cause mortality rates in every age group (AAPCs, −1.84% per year to −3.81% per year; all P < .05) (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). In contrast, all-cause mortality rates among AI/ANs were stable across all age groups, except individuals aged 15 to 19 years, in which significant annual declines occurred (AAPC, −1.93%; 95% CI, −2.9 to −1.0). Among white individuals, there were significant annual declines for all age groups (AAPCs, −1.21% per year to −2.84% per year; all P < .05) except individuals aged 20 to 24 years, whose rates remained stable. Absolute declines in all-cause mortality among all races/ethnicities resulted in an estimated 12 000 fewer deaths in infants and youth in 2015, compared with what was expected based on the rates from 1999 to 2002 (eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

Cause-Specific Mortality Rates by Age Group and Race/Ethnicity

Infants (Age <1 Year)

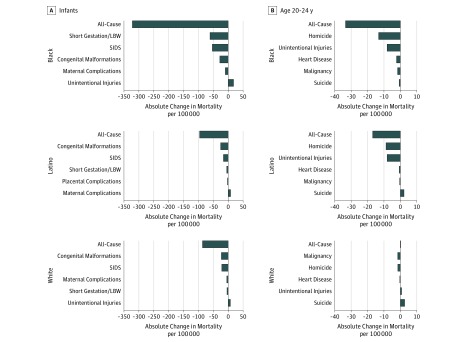

Figure 3 and eTables 4 and 5 in Supplement 1 show the absolute changes in mortality rates for black, Latino, and white infants between 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015 for the 5 leading causes of death. Absolute mortality rates declined among black (−318.70/100 000), Latino (−92.28/100 000), and white (−83.75/100 000) infants, largely driven by declines in sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) (range, −49.94 to −13.10 per 100 000) and congenital malformations (range, −25.31 to −19.73 per 100 000) among all 3 races/ethnicities, and short gestation/low birth weight among black individuals (−58.25/100 000). Black, Latino, and white infants also had notable declines in nonleading causes of death (eFigure 1 in Supplement 1). In contrast, there were increases in unintentional injury deaths among black (18.3/100 000) and white (7.60/100 000) infants and in deaths due to maternal complications of pregnancy among Latino infants (8.99/100 000) (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. Absolute Rate Change Between 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015 for Leading Causes of Death for White, Black, and Latino Individuals .

LBW indicates low birth weight; SIDS, sudden infant death syndrome.

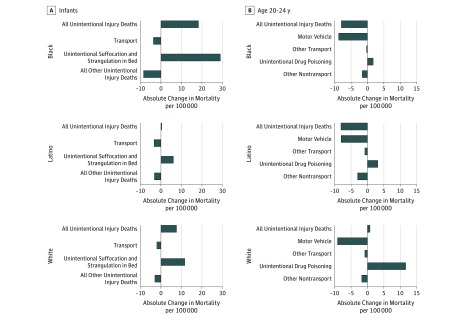

We investigated specific causes of death driving the increase in unintentional injury deaths among infants. Mortality rates due to unintentional transport injuries decreased for all races/ethnicities between 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015 (black, −3.30/100 000; Latino, −3.04/100 000; white, −1.68/100 000) (Figure 4A and eTable 6 in Supplement 1). However, mortality rates due to unintentional suffocation and strangulation in bed increased in all races/ethnicities (black, 29.03/100 000; Latino, 6.11/100 000; white, 11.63/100 000), resulting in approximately 560 additional deaths in 2015 compared with what was expected based on rates from 1999 to 2002.

Figure 4. Absolute Rate Change Between 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015 for Causes of Unintentional Injury Mortality for White, Black, and Latino Individuals.

Children (Age 1-9 Years)

For children, mortality rates decreased in all races/ethnicities for all leading causes of death between 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015 (eFigure 2A and eTables 4 and 7 in Supplement 1). The largest absolute decline was for unintentional injury deaths (−4.66 to −2.61 per 100 000). Declines were also observed for congenital malformations, heart disease, homicide, and malignancies.

Early Adolescents (Age 10-14 Years)

All-cause mortality rates declined between 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015 among individuals aged 10 to 14 years for all races/ethnicities largely due to declines in unintentional injury death rates (black, −4.30/100 000; Latino, −2.59/100 000; white, −3.92/100 000) (eFigure 2B and eTables 4 and 7 in Supplement 1). Mortality due to chronic lower respiratory disease, congenital malformations, heart disease, homicide, and malignancies also declined. However, suicide mortality rates increased slightly in all 3 groups (black, 0.45/100 000; Latino, 0.21/100 000; white, 0.80/100 000).

Late Adolescents (Age 15-19 Years)

Declines between 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015 in all-cause mortality rates occurred among black, Latino, and white individuals aged 15 to 19 years, largely driven by declines in unintentional injury mortality (range, −16.8 to −9.1 per 100 000) in all races/ethnicities and homicide mortality rates (range, −7.5 to −5.1 per 100 000) for black and Latino individuals (eFigure 2B and eTables 4 and 7 in Supplement 1). Declines were also observed in heart disease and malignancy mortality rates. As with early adolescents, suicide mortality rates increased slightly among late adolescents (black, 0.10/100 000; Latinos, 0.39/100 000; white, 1.86/100 000).

Young Adults (Age 20-24 Years)

While all-cause mortality rates declined substantially among black and Latino young adults between 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015 (range: −33.17 to −16.62 per 100 000), rates among white young adults increased slightly (0.21/100 000) (Figure 3B and eTable 4 in Supplement 1). Declines among black and Latino individuals were largely due to decreases in unintentional injury death and homicide rates. Heart disease and malignancy mortality rates decreased across races/ethnicities. Whereas suicide rates among black young adults decreased (−0.36/100 000), rates among white (2.63/100 000) and Latino (2.18/100 000) individuals increased. Unintentional injury death rates also increased among white individuals (0.79/100 000).

Among the major causes of unintentional injury deaths in young adults, deaths due to motor vehicle, other transport, and other nontransport injuries decreased notably across all races/ethnicities, resulting in net decreases in unintentional injury mortality rates in black and Latino individuals (Figure 4B and eTable 8 in Supplement 1) between 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015. However, deaths due to unintentional drug poisonings increased in white (11.70/100 000), black (1.76/100 000), and Latino (3.18/100 000) young adults, resulting in an overall increase in these death rates for white individuals. Rising rates of deaths due to unintentional drug poisonings resulted in an estimated 2100 additional deaths in 2015 over what would have been expected had rates remained stable.

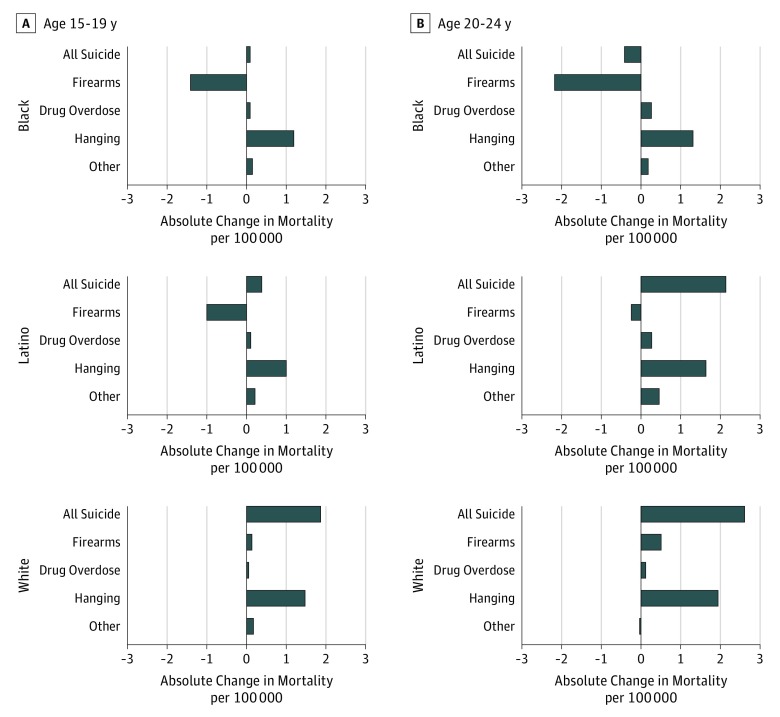

Causes of Suicide

We examined changes in the causes of suicide between 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015 among individuals aged 15 to 19 years and 20 to 24 years (Figure 5 and eTable 9 in Supplement 1). Suicide rates by firearms increased slightly in white individuals aged 15 to 24 years (range, 0.14-0.51 per 100 000) but decreased for black and Latino individuals aged 15 to 24 years. Suicide rates from hanging (range, 1.00-1.95 per 100 000) and drug poisoning (range, 0.06-0.27 per 100 000) increased in all 3 races/ethnicities, with the greatest increases in intentional drug poisoning observed in black and Latino young adults. Rising suicide rates resulted in approximately 1400 additional deaths in 2015 compared with what would have been expected if rates remained stable.

Figure 5. Absolute Rate Change Between 1999 to 2002 and 2012 to 2015 for Means of Suicide in White, Black, and Latino Individuals .

Discussion

From 1999 to 2015, there were substantial declines in all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates in US infants and youth in most age and racial/ethnic groups. By 2015, the United States surpassed Healthy People 2020 goals for a 10% reduction in infant and youth mortality in almost all age groups. Declines are largely attributed to reductions in SIDS and congenital malformations in infants and homicide and unintentional injuries in youth, resulting in approximately 12 000 total averted deaths in 2015, compared with what would have been expected if mortality rates remained stable. Unfortunately, mortality rates remain substantially higher than those in Canada and England/Wales and racial disparities are pronounced. Further, increasing mortality rates were observed for unintentional suffocation and strangulation in bed among infants, and suicide and drug poisonings in adolescents and young adults, resulting in approximately 4000 additional deaths in 2015.

Previous studies observed higher youth mortality rates in Canada and England/Wales than other high-income countries.15 Although mortality rates in US children have improved markedly, they remain even higher and are improving more slowly than in Canada and England/Wales. Further, long-standing racial/ethnic disparities in the United States persist.8,9,19,20 Black individuals had the largest absolute declines in mortality rates in each age group examined; however, in 2015, mortality rates were still higher among black than white individuals across age groups, even among young adults where no improvements were observed among white individuals. These disparities are a result of long-standing social and economic inequality, which influences access of care, quality of care, and attitudes of patients and clinicians.21 The highest mortality rates were consistently observed among AI/ANs, except among infants. Previous studies have attributed elevated mortality rates in AI/ANs to unintentional injury, alcohol and substance use, homicide, and suicide.22,23,24 Additionally, AI/AN communities often have high levels of poverty, unemployment, and limited access to quality education and health care.22,25,26,27

The United States ranks among the lowest of all high-income countries for infant health.2,6,28 The preterm birth rate in the United States is particularly high, and prematurity is a major cause of infant mortality.29,30 The high infant mortality rate in the United States reflects poor maternal health, high adolescent birth rates, and limited access to prenatal care for the socially disadvantaged.31,32 The largest absolute disparities internationally and within the United States were observed for infant mortality. Although the infant mortality rate declined by 20% from 1999 to 2015 (7.36 to 5.90 per 1000), achieving the Healthy People 2020 goal of less than 6 deaths per 1000 infants, 2015 infant mortality rates remained exceptionally high and far from this goal for black individuals (11/1000) and AI/ANs (9.7/1000). There have been substantial declines in low-birth-weight deaths among black infants and congenital malformation and SIDS deaths among all infants, which have been attributed to the 1994 Back-to-Sleep campaign recommending babies lay supine when sleeping.33 Interestingly, our study, as well as others, identified an increase in unintentional suffocation and strangulation in bed in infants across all 3 race/ethnicites.34 This increase may be driven by reclassification of SIDS-related deaths due to improvements in death scene investigation protocol allowing for more accurate cause of death coding.33,35,36,37,38 The number of infant deaths from SIDS remains high, and safe sleep techniques should be reinforced for all infants. We also note that deaths rates due to maternal complications of pregnancy in Latino infants have increased, which warrants further investigation.

Mortality rates among children of all 3 races/ethnicities declined, with the largest declines observed for unintentional injury deaths, attributed to fewer motor vehicle injuries and drownings in previous studies.39,40 Reductions in mortality due to congenital malformations, heart disease, homicide, and cancer also contributed to overall declines.

Among adolescents and young adults in the United States, reductions in unintentional injury and homicide mortality rates contributed substantially to the overall decline in all-cause mortality rates. However, youth mortality rates are higher in the United States than other high-income countries primarily due to higher rates of injury-related deaths, including motor vehicle–related and firearm-related deaths,2,41 which have been increasing in adolescents since 2013.42 Between 2001 and 2012, the firearm-homicide rate among individuals aged 15 to 29 years was 82-times higher in the United States than 19 other high-income countries and increased by about 25% between 2012 to 2014.2,42 Within the United States, black teenagers have even higher homicide and firearm mortality rates than their white and Latino counterparts.8,43,44,45

Of concern, we found a rise in suicide rates among adolescents and young adults across all races/ethnicities, resulting in more than 1700 additional deaths in 2015 compared with what was expected based on rates from 1999 to 2002. Suicides in adolescents have been observed to be increasing since 2007.42 These data do not include nonfatal suicide attempts, which increased almost 19% annually between 2001 to 2015 in individuals aged 10 to 24 years.46 The firearm-suicide rate in the United States is 8-times higher than other high-income countries.41,47 Although previous work has reported decreasing trends in youth suicide by firearms, we have shown that rates actually increased among white youth.48,49,50,51,52 Consistent with prior studies, we found that suicide by hanging and drug poisoning increased in all 3 races/ethnicities and age groups.49,50,52 The American Academy of Pediatrics published guidelines to assist physicians with identifying and treating depression in youth.53,54 Our data show the importance of these recommendations.

The US opioid epidemic is responsible for reducing life expectancy and increasing premature mortality in white adults.55 Increases in drug-related deaths have been observed in adults across all races/ethnicites.56 In 2010, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that for each prescription-related opioid death in the United States, there were 108 individuals who abused or were dependent on opioids and 733 nonmedical users of opioids.57,58 Hospitalizations due to nonfatal drug poisonings increased by 65% between 1999 to 2006.59 In 2014, approximately 53 000 hospitalizations and 92 000 emergency department visits occurred for unintentional, opioid-related poisonings alone.60 Young adults had the highest rate of emergency department visits for prescription opioid poisoning.57,61 We found increases in drug poisoning death rates among black, Latino, and white individuals aged 20 to 24 years. Rising rates of drug poisoning deaths resulted in approximately 2100 unintentional deaths in 2015.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of our study is the comprehensive analysis of infant and youth mortality rates by age, race/ethnicity, and cause of death using data from all deaths in the United States from 1999 to 2015 and comparison with 2 other high-income countries. Limitations include misclassification of the intent of drug poisoning deaths (eg, suicide, unintentional, undetermined intent)62 due to associated stigma, which may underestimate the cause-specific mortality rates and racial/ethnic misclassification on death ceritificates.63 In our data, 5% of all drug poisonings in individuals aged 10 to 24 years had an undetermined intent. To increase the sensitivity of AI/AN ascertainment, we only used counties with health service delivery contracts.18 Further, racial misclassification may have improved over time, which may have led to an underestimation of mortality declines in some groups. Finally, the expected number of deaths were calculated by applying age-specific mortality rates from 1999 to 2002 to the 2015 population; this approach conservatively estimates the number of excess deaths, as ideally rates of all causes of death would decline and not remain stable over the assessed time period.

Conclusions

Despite spending the highest percentage of gross domestic product on health care globally,7 the United States ranks poorly in infant and youth mortality rates. Substantial progress has been made, with reductions in almost all leading causes of death, including unintentional injury, homicide, and malignancies. By 2015, the United States reduced mortality rates below Healthy People 2020 goals in every age group except for young adults. However, striking racial disparities still exist, with black individuals and AI/ANs still far from reaching target goals in certain age groups, with particularly large disparities observed for infant mortality. Furthermore, improvements in mortality rates among young white adults in the United States have stagnated owing to increases in unintentional drug poisonings and suicide. Suicide and drug poisoning rates have also risen for black and Latino youth, highlighting the urgent need for policies and interventions that aim to prevent these deaths.

eTable 1. ICD-10 Codes for Specific Causes of Death

eTable 2. Average Annual Percent Changes in mortality rates for the U.S., Canada and England/Wales, 1999-2015

eTable 3. Average annual percent change for all-cause mortality by age and race/ethnicity in the U.S.

eTable 4. Absolute Change in All-Cause Mortality between 1999-2002 & 2012-2015

eTable 5. Absolute Change for Leading Causes of Infant Mortality between 1999-2002 & 2012-2015

eTable 6. Absolute Change for Specific Causes of Unintentional Injury Mortality in Infants between 1999-2002 and 2012-2015

eTable 7. Absolute Change for Leading Causes of Youth Mortality between 1999-2002 & 2012-2015

eTable 8. Absolute Change for Specific Causes of Unintentional Injury Deaths in 20-24-year-olds between 1999-2002 and 2012-2015

eTable 9. Absolute Change for Means of Suicide between 1999-2002 and 2012-2015

eFigure 1. Non-Leading Causes of Death for White, Black and Latino Infants

eFigure 2. Absolute rate change between 1999-2002 and 2012-2015 for leading causes of death for White, Black and Latino A) 1-9-year-olds and B) 10-14-year-olds, and C)15-19-year-olds. All rates are expressed per 100,000

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Viner RM, Coffey C, Mathers C, et al. 50-Year mortality trends in children and young people: a study of 50 low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries. Lancet. 2011;377(9772):-. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60106-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thakrar AP, Forrest AD, Maltenfort MG, Forrest CB. Child mortality in the US and 19 OECD comparator nations: a 50-year time-trend analysis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(1):140-149. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Curtin SC, Arias E. Deaths: Final Data for 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2017;66(6):1-75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC on Infectious Diseases in the United States 1900-99. Popul Dev Rev. 1999;25(3):635-640. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.1999.00635.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pritchard C, Williams R. Poverty and child (0-14 years) mortality in the USA and other Western countries as an indicator of “how well a country meets the needs of its children” (UNICEF). Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2011;23(3):251-255. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2011.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacDorman MF, Matthews TJ, Mohangoo AD, Zeitlin J. International comparisons of infant mortality and related factors: United States and Europe, 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2014;63(5):1-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Statistics National Center for Health Statistics Health Expenditures. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm. Accessed April 27, 2018.

- 8.Oberg C, Colianni S, King-Schultz L. Child health disparities in the 21st century. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2016;46(9):291-312. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2016.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Eke PI, Giles WH. Vital signs: racial disparities in age-specific mortality among blacks or African Americans: United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(17):444-456. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riddell CA, Harper S, Kaufman JS. Trends in differences in US mortality rates between black and white infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(9):911-913. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1365 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtin SC, Tejada-Vera B, Warmer M. Drug overdose deaths among adolescents aged 15-19 in the United States: 1999-2015. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(282):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2016;(241):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh GK, Yu SM. US childhood mortality, 1950 through 1993: trends and socioeconomic diffferentials. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(4):505-512. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.86.4.505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh GK, Azuine RE, Siahpush M, Kogan MD. All-cause and cause-specific mortality among US youth: socioeconomic and rural-urban disparities and international patterns. J Urban Health. 2013;90(3):388-405. doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9744-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viner RM, Hargreaves DS, Coffey C, Patton GC, Wolfe I. Deaths in young people aged 0-24 years in the UK compared with the EU15+ countries, 1970-2008: analysis of the WHO Mortality Database. Lancet. 2014;384(9946):880-892. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60485-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deaths Registered in England and Wales Office for National Statistics. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsregistrationsummarytables/2016.

- 17.Deaths and mortality rates, by age group and sex, Canada, provinces and territories. Statistics Canada. http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a47. Accessed April 4, 2018.

- 18.Jim MA, Arias E, Seneca DS, et al. Racial misclassification of American Indians and Alaska Natives by Indian Health Service contract health service delivery area. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 3):S295-S302. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Howell E, Decker S, Hogan S, Yemane A, Foster J. Declining child mortality and continuing racial disparities in the era of the Medicaid and SCHIP insurance coverage expansions. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2500-2506. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hauck FR, Tanabe KO, Moon RY. Racial and ethnic disparities in infant mortality. Semin Perinatol. 2011;35(4):209-220. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holck P, Day GE, Provost E. Mortality trends among Alaska Native people: successes and challenges. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2013;72(1):21185. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutman S, Park A, Castor M, Taualii M, Forquera R. Urban American Indian and Alaska Native youth: youth risk behavior survey 1997-2003. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12(suppl 1):76-81. doi: 10.1007/s10995-008-0351-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Committee on Native American Child Health and Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. American Academy of Pediatrics The prevention of unintentional injury among American Indian and Alaska Native children: a subject review. Pediatrics. 1999;104(6):1397-1399. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.6.1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warne D, Frizzell LB. American Indian health policy: historical trends and contemporary issues. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(suppl 3):S263-S267. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kunitz SJ, Veazie M, Henderson JA. Historical trends and regional differences in all-cause and amenable mortality among American Indians and Alaska Natives since 1950. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S3)(suppl 3):S268-S277. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Espey DK, Jim MA, Cobb N, et al. Leading causes of death and all-cause mortality in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3)(suppl 3):S303-S311. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adamson P. Child Well-Being in Rich Countries, a Comparative Overview. Florence, Italy: UNICEF Office of Research; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matthews TJ, MacDorman MF, Thoma ME. Infant mortality statistics from the 2013 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(9):1-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacob JA. US infant mortality rate declines but still exceeds other developed countries. JAMA. 2016;315(5):451-452. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sedgh G, Finer LB, Bankole A, Eilers MA, Singh S. Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: levels and recent trends. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56(2):223-230. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.GBD 2015 Maternal Mortality Collaborators Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1775-1812. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31470-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome The changing concept of sudden infant death syndrome: diagnostic coding shifts, controversies regarding the sleeping environment, and new variables to consider in reducing risk. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1245-1255. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao Y, Schwebel DC, Hu G. Infant mortality due to unintentional suffocation among infants younger than 1 year in the United States, 1999-2015. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172(4):388-390. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.4887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Tomashek KM, Anderson RN, Wingo J. Recent national trends in sudden, unexpected infant deaths: more evidence supporting a change in classification or reporting. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(8):762-769. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malloy MH, MacDorman M. Changes in the classification of sudden unexpected infant deaths: United States, 1992-2001. Pediatrics. 2005;115(5):1247-1253. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carlberg MM, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Goodman M. Maternal and infant characteristics associated with accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed in US infants. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(8):1594-1601. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0855-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Kimball M, Tomashek KM, Anderson RN, Blanding S. US infant mortality trends attributable to accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed from 1984 through 2004: are rates increasing? Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):533-539. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mannix R, Fleegler E, Meehan WP III, et al. Booster seat laws and fatalities in children 4 to 7 years of age. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):996-1002. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bowman SM, Aitken ME, Robbins JM, Baker SP. Trends in US pediatric drowning hospitalizations, 1993-2008. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):275-281. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richardson EG, Hemenway D. Homicide, suicide, and unintentional firearm fatality: comparing the United States with other high-income countries, 2003. J Trauma. 2011;70(1):238-243. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181dbaddf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curtin SC, Heron M, Miniño AM, Warner M. Recent increases in injury mortality among children and adolescents aged 10-19 years in the United States: 1999-2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(4):1-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bernard SJ, Paulozzi LJ, Wallace DL; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Fatal injuries among children by race and ethnicity: United States, 1999-2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2007;56(5):1-16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Logan JE, Smith SG, Stevens MR; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Homicides: United States, 1999-2007. MMWR Suppl. 2011;60(1):67-70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miniño A. Mortality among teenagers aged 12-19 years: United States, 1999-2006. NCHS Data Brief. 2010;(37):1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mercado MC, Holland K, Leemis RW, Stone DM, Wang J. Trends in emergency department visits for nonfatal self-inflicted injuries among youth aged 10 to 24 years in the United States, 2001-2015. JAMA. 2017;318(19):1931-1933. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grinshteyn E, Hemenway D. Violent death rates: the US compared with other high-income OECD countries, 2010. Am J Med. 2016;129(3):266-273. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bridge JA, Asti L, Horowitz LM, et al. Suicide trends among elementary school-aged children in the United States from 1993 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(7):673-677. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bridge JA, Greenhouse JB, Sheftall AH, Fabio A, Campo JV, Kelleher KJ. Changes in suicide rates by hanging and/or suffocation and firearms among young persons aged 10-24 years in the United States: 1992-2006. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(5):503-505. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sullivan EM, Annest JL, Simon TR, Luo F, Dahlberg LL; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Suicide trends among persons aged 10-24 years: United States, 1994-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(8):201-205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baker SP, Hu G, Wilcox HC, Baker TD. Increase in suicide by hanging/suffocation in the U.S., 2000-2010. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(2):146-149. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skinner R, McFaull S. Suicide among children and adolescents in Canada: trends and sex differences, 1980-2008. CMAJ. 2012;184(9):1029-1034. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.111867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zuckerbrot RA, Cheung A, Jensen PS, Stein REK, Laraque D; GLAD-PC STEERING GROUP . Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): part I: practice preparation, identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20174081. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Laraque D, Stein REK; GLAD-PC STEERING GROUP . Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): part II: treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20174082. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shiels MS, Chernyavskiy P, Anderson WF, et al. Trends in premature mortality in the USA by sex, race, and ethnicity from 1999 to 2014: an analysis of death certificate data. Lancet. 2017;389(10073):1043-1054. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30187-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shiels MS, Freedman ND, Thomas D, Berrington de Gonzalez A. Trends in U.S. drug overdose deaths in non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white persons, 2000-2015. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(6):453-455. doi: 10.7326/M17-1812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Prescription drug abuse and overdose: public health perspective. Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing. http://www.supportprop.org/resources/prescription-drug-abuse-and-overdose-public-health-perspective/. Accessed August 23, 2018.

- 59.Coben JH, Davis SM, Furbee PM, Sikora RD, Tillotson RD, Bossarte RM. Hospitalizations for poisoning by prescription opioids, sedatives, and tranquilizers. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(5):517-524. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Annual Surveillance Report of Drug-Related Risks and Outcomes: United States, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tadros A, Layman SM, Davis SM, Davidov DM, Cimino S. Emergency visits for prescription opioid poisonings. J Emerg Med. 2015;49(6):871-877. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.06.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hawton K, Saunders KE, O’Connor RC. Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet. 2012;379(9834):2373-2382. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arias E, Heron M, Hakes J; National Center for Health Statistics; US Census Bureau . The validity of race and Hispanic-origin reporting on death certificates in the United States: an update. Vital Health Stat 2. 2016;(172):1-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. ICD-10 Codes for Specific Causes of Death

eTable 2. Average Annual Percent Changes in mortality rates for the U.S., Canada and England/Wales, 1999-2015

eTable 3. Average annual percent change for all-cause mortality by age and race/ethnicity in the U.S.

eTable 4. Absolute Change in All-Cause Mortality between 1999-2002 & 2012-2015

eTable 5. Absolute Change for Leading Causes of Infant Mortality between 1999-2002 & 2012-2015

eTable 6. Absolute Change for Specific Causes of Unintentional Injury Mortality in Infants between 1999-2002 and 2012-2015

eTable 7. Absolute Change for Leading Causes of Youth Mortality between 1999-2002 & 2012-2015

eTable 8. Absolute Change for Specific Causes of Unintentional Injury Deaths in 20-24-year-olds between 1999-2002 and 2012-2015

eTable 9. Absolute Change for Means of Suicide between 1999-2002 and 2012-2015

eFigure 1. Non-Leading Causes of Death for White, Black and Latino Infants

eFigure 2. Absolute rate change between 1999-2002 and 2012-2015 for leading causes of death for White, Black and Latino A) 1-9-year-olds and B) 10-14-year-olds, and C)15-19-year-olds. All rates are expressed per 100,000

Data Sharing Statement