Key Points

Question

Was there an association between the US Department of Justice (DOJ) investigation into placement of primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) and changes in the proportion of ICDs not meeting the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services National Coverage Determination (NCD)?

Findings

In this retrospective cohort study of 300 151 primary prevention ICDs conducted from 2007 through 2015 at 1809 US hospitals (including 452 that settled with the DOJ), there were significant decreases in the proportion of primary prevention ICDs not meeting NCD criteria at all hospitals, with larger and more rapid decreases after the announcement of the investigation at hospitals that settled with the DOJ. There were similar decreases observed among non–Medicare beneficiaries.

Meaning

The Department of Justice investigation was associated with significant decreases in implantable cardioverter-defibrillators not meeting National Coverage Determination criteria at all hospitals, including patient populations that were not the focus of the investigation.

Abstract

Importance

The US Department of Justice (DOJ) conducted an investigation into implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) not meeting the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services National Coverage Determination (NCD) criteria.

Objective

To examine changes in the proportion of initial primary prevention ICDs that did not meet NCD criteria following the announcement of the DOJ investigation at hospitals that reached settlements (settlement hospitals) and those that did not (nonsettlement hospitals).

Design, Setting, and Participants

Multicenter, longitudinal, serial cross-sectional analysis of 300 151 initial primary prevention ICDs among Medicare beneficiaries from January 1, 2007, through December 31, 2015, at 1809 US hospitals in the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) ICD Registry, of which 452 hospitals (with 99 591 primary prevention ICDs) reached settlements with the DOJ.

Exposures

The DOJ investigation announcement in 2010.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Proportion of initial primary prevention ICDs not meeting NCD criteria.

Results

In January 2007, the proportion of initial ICDs not meeting NCD criteria was 25.8% (95% CI, 24.7% to 26.8%) at settlement hospitals and 22.8% (95% CI, 22.1% to 23.5%) at nonsettlement hospitals (P < .001). Over the study period, there was a 62.7% (95% CI, 59.2% to 66.1%) relative decrease and 16.1% (95% CI, 14.8% to 17.5%) absolute decrease in the proportion of ICDs not meeting NCD criteria at settlement hospitals compared with a 53.2% (95% CI, 50.4% to 56.0%) relative decrease and 12.1% (95% CI, 11.2% to 13.0%) absolute decrease in proportion at nonsettlement hospitals (P < .001 for both; P for interaction < .001). Trends significantly differed between hospital groups only in the period following the announcement of the DOJ investigation (January 2010-June 2011), with larger and more rapid decreases at settlement hospitals (P for interaction = .01). Over the study period, there was a 32.8% (95% CI, 29.9% to 35.7%) relative decrease and a 1703 ICDs (95% CI, 1520 to 1886) absolute decrease in the volume of primary prevention ICDs implanted at settlement hospitals compared with a 17.4% (95% CI, 14.8% to 20.0%) relative decrease and a 1495 ICDs (95% CI, 1249 to 1741) absolute decrease in volume at nonsettlement hospitals (P < .001 for both; P for interaction < .001), with more modest decreases or slight increases in secondary prevention ICD volume. These patterns were similar when examining ICD utilization among non–Medicare beneficiaries.

Conclusions and Relevance

From 2007 through 2015, the volume of primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and the proportion of devices not meeting the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services National Coverage Determination criteria decreased at all hospitals with substantially larger decreases at hospitals that reached settlements in the US Department of Justice investigation. These patterns extended to implantable cardioverter-defibrillators placed in non–Medicare beneficiaries, which were not the focus of the US Department of Justice investigation.

This cross-sectional analysis uses data from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry to examine changes in the proportion of initial primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillators placed that did not meet the CMS National Coverage Determination following the announcement of the US Department of Justice investigation at hospitals that did and did not reach settlements.

Introduction

Randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) improve the survival of selected patients at increased risk of sudden cardiac death.1,2,3 The pivotal trials for primary prevention (implanted in individuals at increased risk for ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death) ICDs excluded patients who had a recent acute myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization, and both newly diagnosed and advanced heart failure. Moreover, other clinical trials failed to demonstrate a survival benefit with ICDs placed prophylactically among patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery or early after an acute myocardial infarction.4,5,6 In 2005, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) developed a National Coverage Determination (NCD) for ICDs, which incorporated this information and aligned payment for primary prevention ICD implants with the available clinical evidence.7,8,9

In 2010, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) notified hospitals of an investigation into potential overuse of ICDs in violation of the False Claims Act; the existence of the investigation was made public in January 2011. Contemporaneously, a study demonstrated that 22.5% of primary prevention devices were not aligned with NCD criteria.10 By February 2016, the DOJ concluded its investigation, reaching settlements with more than 500 hospitals that exceeded $280 million.11,12,13

The purpose of this study was to examine whether the proportion of initial primary prevention ICDs that did not meet the CMS NCD criteria changed following the announcement of the DOJ investigation and whether trends varied among hospitals that did reach settlements in the investigation (settlement hospitals) and those that did not (nonsettlement hospitals). In addition, changes in the volume of initial secondary prevention ICDs (implanted in individuals with a history of sustained ventricular arrhythmia or cardiac arrest) were assessed as a potential signal of unintended consequences of the DOJ investigation.

Methods

Data Source

Details of the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR)—ICD Registry have been described previously.14,15 In brief, the registry was created to satisfy a reimbursement requirement from CMS for primary prevention ICDs and has more than 1800 participating hospitals. It includes detailed information collected by trained staff using a standardized data collection form.16 Data submissions must meet specified quality standards and randomly identified sites are subject to audits.17 The Human Investigation Committee of the Yale University School of Medicine approved the use of a limited data set from the NCDR for research and granted a waiver of informed consent.

US Department of Justice Investigation

The DOJ investigation began in 2008 with the submission of a whistle-blower complaint against approximately 1300 hospitals under the False Claims Act (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Hospitals were notified of an investigation of ICDs that did not meet NCD criteria starting in early 2010 when the DOJ sent civil investigative demands.13,18 In January 2011, the Heart Rhythm Society notified its members of the active DOJ investigation and released a public statement on the investigation.19 In October 2015, the DOJ announced settlements with 457 hospitals in 43 states for more than $250 million related to ICDs in Medicare beneficiaries that did not meet NCD criteria.11 Additional settlements of more than $23 million were announced in February 2016 with 51 hospitals for a total of 502 unique hospitals.12

Study Cohort and DOJ Settlement Status

Initial primary prevention ICD implantations for ischemic or nonischemic cardiomyopathy among Medicare beneficiaries between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2015, were identified in the NCDR ICD Registry. More recent ICD implants could not be included due to the release of a new version of the ICD Registry data collection form in April 2016. We stratified the population based upon whether the implanting hospital had paid a settlement as part of the DOJ investigation. The 502 hospitals that reached settlements with the DOJ were publicly named and were matched to facilities in the NCDR ICD Registry.11,12 Of these 502 facilities, we were able to match 470 facilities (93.6%) in the ICD Registry.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the proportion of initial primary prevention ICD implantations among Medicare beneficiaries that did not meet CMS NCD criteria at each 6-month interval. ICDs not meeting the NCD criteria were identified using methods and definitions applied in prior analyses.10 Specifically, among Medicare beneficiaries with prior myocardial infarction and ejection fraction less than or equal to 30% or any congestive heart failure and ejection fraction less than or equal to 35%, patients were classified as receiving an ICD that did not meet NCD criteria for the following reasons: the individual (1) had a myocardial infarction within 40 days before ICD implantation; (2) had CABG surgery within 3 months before ICD implantation; (3) had New York Heart Association class IV symptoms without receiving concomitant cardiac resynchronization therapy; or (4) had newly diagnosed heart failure at the time of ICD implantation.7,10 Additional outcomes included the volume of initial primary and secondary prevention ICDs over time and the proportion of initial primary prevention ICDs not meeting the CMS NCD criteria among non–Medicare beneficiaries.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed either at the patient level or the hospital level. For patient-level analyses, all primary prevention ICD implantations were included. Records lacking documentation of the data elements required to determine whether the ICD met the CMS NCD criteria as well as those from hospitals that did not meet the NCDR data quality standards were excluded from the analysis.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between settlement hospitals and nonsettlement hospitals. The proportion of ICDs that did not meet CMS NCD criteria were calculated for each 6-month interval and compared over time, stratified by hospital settlement group.

To examine associations with the DOJ investigation, we used an interrupted time series to investigate changes in the proportion of ICDs not meeting the NCD criteria. This nonexperimental design is often used to estimate the associations with a policy intervention or other natural experiment provided there are at least 4 data points both before and after the event of interest.20,21 The interrupted time series model was fit using a linear probability autoregressive model. We calculated estimates of the proportion of ICDs not meeting CMS NCD criteria during each month accounting for seasonal autocorrelation stratified by DOJ settlement status. Based on the timing of hospital notification of the DOJ investigation, the model was designed to evaluate 3 periods: before the DOJ investigation announcement (January 2007-December 2009); DOJ investigation announcement (January 2010-June 2011); and after the DOJ investigation announcement (July 2011-December 2015). Hospitals were notified of the DOJ investigation as early as January 2010 with public announcement of the investigation by the Heart Rhythm Society in January 2011. The announcement period, January 2010 through June 2011, comprises the period when the investigation would have first impacted ICD utilization and patient selection. We compared the slope of the proportion of ICDs not meeting the CMS NCD criteria during these 3 periods stratified by DOJ settlement status, annualizing rates of change.

For hospital-level analyses, we required hospitals to have participated in the NCDR ICD Registry over the entire study period, and to have performed at least 10 primary prevention ICD implants in each year.10 Baseline hospital characteristics were compared with standardized differences. The proportion of ICDs that did not meet the CMS NCD was determined by aggregating all primary prevention ICDs among Medicare beneficiaries in the calendar year to calculate a hospital-specific estimate, again stratifying by the hospital’s settlement status, and displayed using box plots. Top and bottom performing hospitals were defined as facilities in the first and fourth quartile of performance. The volume of initial primary and secondary prevention ICDs was examined over time, stratifying by DOJ settlement status. The patient-level and hospital-level analyses were repeated among non–Medicare beneficiaries to determine whether the DOJ investigation affected the broader population of patients undergoing ICD implantation.

As a negative control to assess how secular changes might have affected associations of the DOJ investigation with practice patterns, we examined the volume of ICD generator changes for the end of battery life and device upgrades (single-chamber to dual-chamber ICD or ICD to cardiac resynchronization therapy device) over the study period. For this analysis, we included implants in Medicare beneficiaries performed at hospitals continuously participating in the ICD Registry and performing at least 1 such case in each year. These implants were performed for well-defined populations and clinical indications that were independent of the NCD and therefore would provide additional insight into whether the observed changes among primary prevention ICDs were consistent with secular trends in procedural utilization or represented direct associations with the DOJ investigation.

All analyses were conducted using SAS software (SAS Institute), version 9.4. All tests for statistical significance were 2-tailed and evaluated with a P value less than .05 for significance.

Results

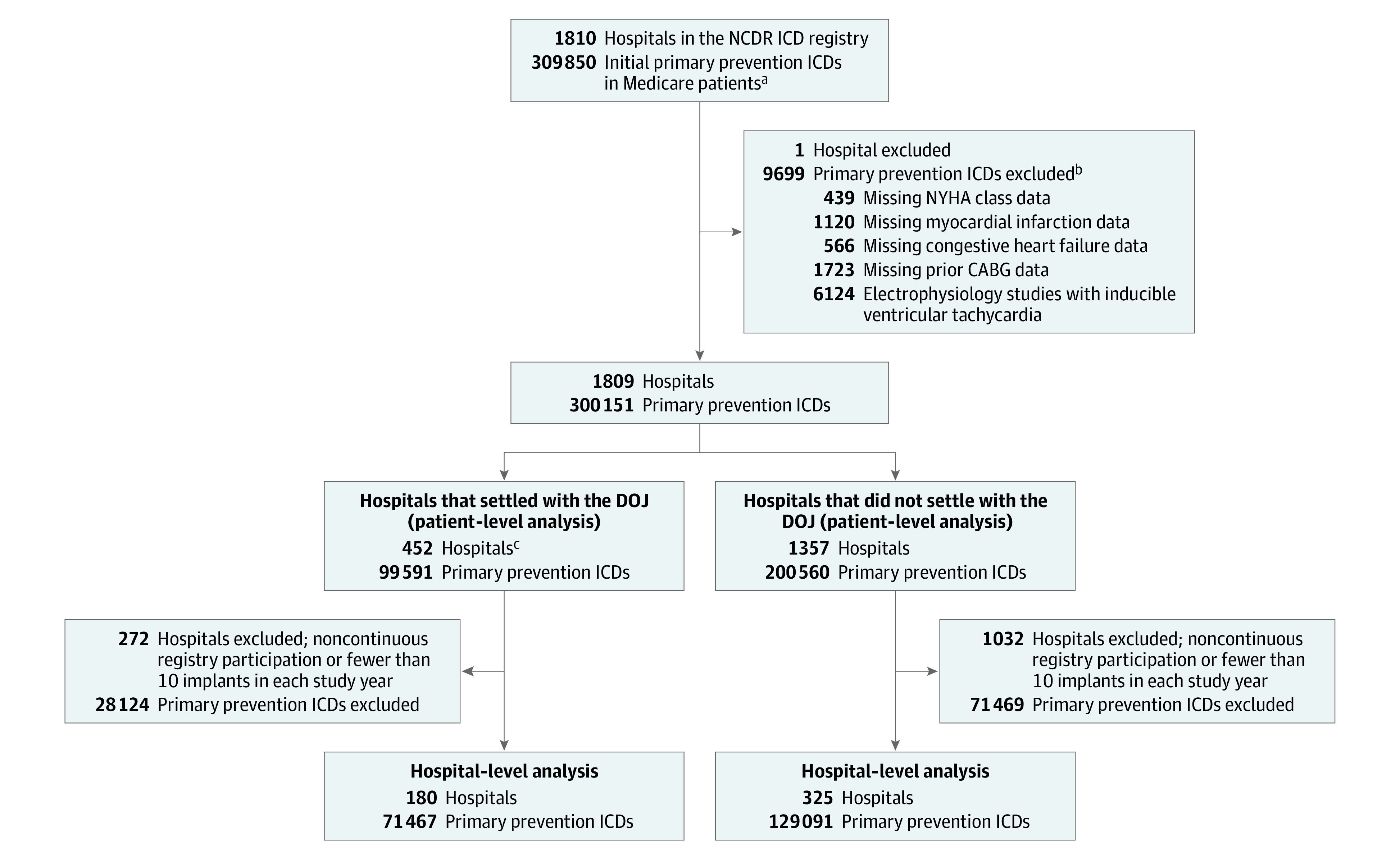

There were a total of 309 850 initial primary prevention ICDs in Medicare beneficiaries across 1810 hospitals between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2015, in the NCDR ICD Registry. A total of 9699 device implants and 1 hospital were excluded from the analysis due to incomplete data, yielding a study cohort of 300 151 primary prevention ICDs at 1809 hospitals (Figure 1). Of the 470 hospitals that had reached settlements with the DOJ and were matched to the NCDR ICD Registry, 2 were confirmed as having closed and 16 did not submit data or their data did not meet NCDR quality standards. Settlement hospitals (n = 452) implanted 99 591 primary prevention ICDs whereas nonsettlement hospitals (n = 1357) implanted 200 560 primary prevention ICDs. Hospital-level analyses included a total of 505 hospitals (180 settlement hospitals and 325 nonsettlement hospitals) and 200 558 ICDs (71 467 at settlement hospitals and 129 091 at nonsettlement hospitals).

Figure 1. Flow of Patients and Hospitals With Initial Primary Prevention ICDs Among Medicare Beneficiaries Through the Study.

CABG indicates coronary artery bypass graft; CHF, congestive heart failure; DOJ, US Department of Justice; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

aFrom January 1, 2007, though December 31, 2015, there were 309 850 initial primary prevention ICDs for Medicare beneficiaries included in the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) ICD Registry database.

bTotal excluded ICDs was less than the sum of causes listed because patient records could have >1 missing data element.

cThese 452 hospitals settled with the DOJ and were included in the study cohort. The DOJ announced settlements with a total of 502 hospitals, of which 470 hospitals (93.6%) were matched to the NCDR ICD Registry. Of these 470 hospitals, 2 hospitals were excluded because they were closed and 16 were excluded because they did not have data submitted to the registry or submitted data that did not meet NCDR quality standards.

Baseline Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients undergoing ICD implantation at settlement hospitals and nonsettlement hospitals are shown in the Table. The mean age was 75.1 years (SD, 6.3), 71.5% were men, 41.8% had diabetes, 54.4% had a prior myocardial infarction, and the mean ejection fraction was 25.0% (SD, 6.2%). The majority of patients received CRT defibrillator devices (53.0%) with 28.9% receiving dual-chamber ICDs and 18.2% receiving single-chamber ICDs. There were no clinically meaningful differences between patients receiving ICDs at settlement hospitals compared with nonsettlement hospitals. Additional hospital characteristics are provided in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Settlement hospitals were larger, private facilities with higher procedural volumes, and were more likely located in the South and West geographic regions.

Table. Characteristics of Medicare Beneficiaries by Hospital Settlement Status With the US Department of Justice (DOJ).

| Patient Characteristics | Total Samplea | Hospital Settlement Status With the DOJ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Settled | Did Not Settle | ||||

| No. of ICD procedures (%) | 300 151 (100.0) | 99 591 (33.2) | 200 560 (66.8) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 75.1 (6.3) | 75.2 (6.4) | 75.1 (6.3) | ||

| Women | 85 632 (28.5) | 28 624 (28.7) | 57 008 (28.4) | ||

| Insurance | |||||

| Medicare only | 100 589 (33.5) | 33 318 (33.5) | 67 271 (33.5) | ||

| Medicare and private | 165 034 (55.0) | 54 597 (54.8) | 110 437 (55.1) | ||

| Medicare and other | 34 528 (11.5) | 11 676 (11.7) | 22 852 (11.4) | ||

| Prior history | |||||

| Prior myocardial infarction | |||||

| No | 133 863 (44.6) | 44 216 (44.4) | 89 647 (44.7) | ||

| Yes ≤40 d of ICD implant | 11 357 (3.8) | 4107 (4.1) | 7250 (3.6) | ||

| Yes >40 d since ICD implant | 154 931 (51.6) | 51 268 (51.5) | 103 663 (51.7) | ||

| Atrial fibrillation and flutter | 121 655 (40.6) | 40 664 (40.9) | 80 991 (40.4) | ||

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 113 492 (37.8) | 38 308 (38.5) | 75 184 (37.5) | ||

| Cerebrovascular accident | 52 637 (17.6) | 17 235 (17.3) | 35 402 (17.7) | ||

| Diabetes | 125 267 (41.8) | 41 550 (41.8) | 83 717 (41.8) | ||

| Hypertension | 252 027 (84.0) | 84 058 (84.5) | 167 969 (83.8) | ||

| End-stage renal disease | 9388 (3.1) | 3337 (3.4) | 6051 (3.0) | ||

| Heart failure | 286 351 (95.4) | 95 069 (95.5) | 191 282 (95.4) | ||

| Heart failure duration | |||||

| <3 mo | 31 673 (11.1) | 10 988 (11.6) | 20 685 (10.8) | ||

| 3 to 9 mo | 55 340 (19.3) | 18 857 (19.8) | 36 483 (19.1) | ||

| >9 mo | 199 338 (69.6) | 65 224 (68.6) | 134 114 (70.1) | ||

| LVEF, mean (SD), % | 25.0 (6.2) | 25.0 (6.3) | 25.0 (6.2) | ||

| New York Heart Association classb | |||||

| I | 11 413 (3.8) | 3514 (3.5) | 7899 (3.9) | ||

| II | 94 774 (31.6) | 29 607 (29.7) | 65 167 (32.5) | ||

| III | 182 891 (60.9) | 62 543 (62.8) | 120 348 (60.0) | ||

| IV | 11 073 (3.7) | 3927 (3.9) | 7146 (3.6) | ||

| QRS duration, mean (SD), ms | 132 (32.6) | 132 (32.6) | 132 (32.7) | ||

| ICD type | |||||

| Single | 54 566 (18.2) | 15 996 (16.1) | 38 570 (19.2) | ||

| Dual | 86 660 (28.9) | 28 742 (28.9) | 57 918 (28.9) | ||

| CRT-D | 158 925 (53.0) | 54 853 (55.1) | 104 072 (51.9) | ||

Abbreviations: CRT-D, cardiac resynchronization therapy implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

Total sample includes all Medicare beneficiaries who received primary prevention ICDs between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2015, with complete data in the NCDR registry.

Class I indicates no limitation or physical activity; class II, slight limitation of physical activity; class III, marked limitation of physical activity; and class IV, unable to carry on any physical activity without discomfort.

ICDs That Did Not Meet NCD Criteria Among Medicare Beneficiaries

The proportion of ICDs that did not meet the CMS NCD criteria at the patient level is displayed in 6-month intervals in Figure 2. In the first half of 2007, 25.8% (95% CI, 24.7% to 26.8%) of ICD implants at hospitals that reached settlements with the DOJ and 22.8% (95% CI, 22.1% to 23.5%) of ICDs at nonsettlement hospitals did not meet the NCD criteria (P < .001). Over the study period, there was a statistically significant 62.7% (95% CI, 59.2% to 66.1%) relative decrease and 16.1% (95% CI, 14.8% to 17.5%) absolute decrease in ICDs not meeting the NCD criteria at settlement hospitals and a 53.2% (95% CI, 50.4% to 56.0%) relative decrease and a 12.1% (95% CI, 11.2% to 13.0%) absolute decrease at nonsettlement hospitals (P < .001 for both; P for interaction < .001).

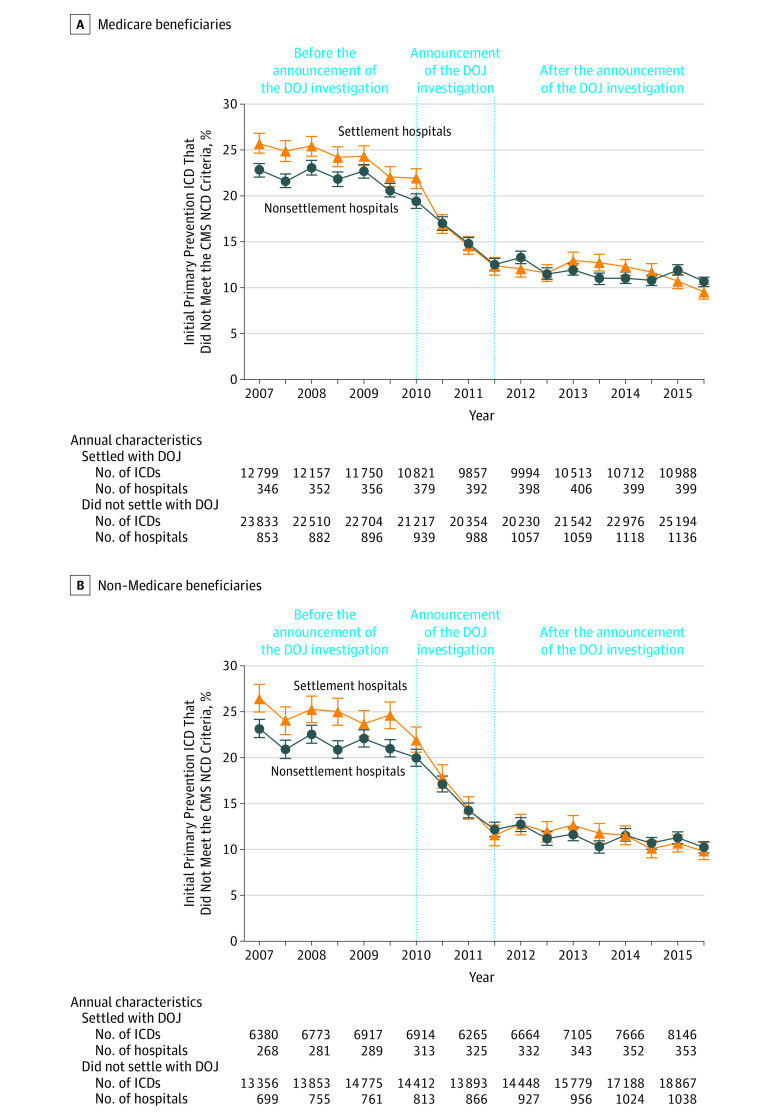

Figure 2. Proportion of Initial Primary Prevention ICDs That Did Not Meet CMS NCD Criteria in Medicare Beneficiaries and Non–Medicare Beneficiaries by Hospital DOJ Settlement Status at the Patient Level, Interrupted Time Series Analysis.

CMS indicates Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; DOJ, US Department of Justice; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; NCD, National Coverage Determination. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. The interrupted time series analysis was fit using a linear probability autoregressive model. Estimates were calculated of the proportion of ICDs not meeting CMS NCD criteria during each month while accounting for seasonal autocorrelation and stratifying by hospital DOJ settlement status (settlement hospitals or nonsettlement hospitals). The model was designed to evaluate the 3 periods: before the DOJ investigation announcement (January 2007-December 2009); the DOJ investigation announcement (January 2010-June 2011); and after the DOJ investigation announcement (July 2011-December 2015). Hospitals were notified of the DOJ investigation as early as January 2010 with public announcement of the investigation by the Heart Rhythm Society in January 2011. The announcement period, January 2010 through June 2011, comprises the period when the investigation would have first impacted ICD utilization and patient selection. We compared the slope of the percentage of ICD implantations outside the CMS NCD during these periods for hospitals that did and did not settle and annualized the rates of change. A, The annualized rates of change for each period: before the DOJ announcement, −1.1% (95% CI, −1.7% to −0.5%) for settlement hospitals vs −0.4% (95% CI −1.0% to 0.2%) for nonsettlement hospitals (P for interaction = .10); the DOJ announcement period, −7.4% (95% CI, −8.9% to −5.9%) for settlement hospitals vs −4.7% (95% CI, −6.2% to −3.2%) for nonsettlement hospitals (P for interaction = .01); after the DOJ announcement, −0.5% (95% CI, −0.9% to −0.2%) for settlement hospitals vs −0.4% (95% CI, −0.8% to −0.1%) for nonsettlement hospitals (P for interaction = .71).

These overall changes are attributable to 3 distinct trends illustrated in the interrupted time series analysis (Figure 2A). From January 2007 through December 2009, the period before the announcement of the DOJ investigation, the proportion of primary prevention ICDs not meeting NCD criteria was relatively stable and the rate of decline was modest and similar among hospital settlement groups (annualized change: −1.1% [95% CI, −1.7% to −0.5%] among settlement hospitals vs −0.4% [−1.0% to 0.2%] among nonsettlement hospitals; P for interaction = .10). From January 2010 through July 2011, there were significant decreases in the proportion of ICDs not meeting the NCD criteria among both hospital settlement groups. However, the rate of decline was significantly larger and more rapid at settlement hospitals compared with nonsettlement hospitals (annualized change: −7.4% [−8.9% to −5.9%] among settlement hospitals vs −4.7% [−6.2% to −3.2%] among nonsettlement hospitals; P for interaction = .01). From July 2011 through December 2015, the proportion of ICDs not meeting the NCD criteria were similar and stable in both hospital settlement groups with an annual change of −0.5% (95% CI, −0.9% to −0.2%) for settlement hospitals and −0.4% (95% CI, −0.8% to −0.1%) for nonsettlement hospitals (P for interaction = .71).

Trends in the proportion of ICDs not meeting the NCD criteria at the hospital level were similar to patient-level trends (eFigure 2 in the Supplement). Although there were significant decreases in ICDs not meeting the NCD criteria, there was persistent variation in performance in 2015 with top-performing facilities having less than 3.8% of ICDs not meeting the NCD criteria whereas lower-performing hospitals had more than 14.3% of ICDs not meeting the NCD criteria.

ICDs That Did Not Meet NCD Criteria Among Non–Medicare Beneficiaries

Trends in the proportion of primary prevention ICDs not meeting the NCD criteria among non–Medicare beneficiaries stratified by hospital settlement group were similar to those among Medicare beneficiaries (Figure 2B) with significant reductions at both groups of hospitals. There was a 62.9% (95% CI, 58.8% to 67.0%) relative and 16.6% (95% CI, 14.9% to 18.4%) absolute reduction at settlement hospitals and 55.8% (95% CI, 52.6% to 59.1%) relative and 12.9% (95% CI, 11.8% to 14.1%) absolute reduction at nonsettlement hospitals in the proportion of ICDs not meeting the NCD criteria among non–Medicare beneficiaries (P < .001 for both; P for interaction < .001).

Volume of Primary and Secondary Prevention ICDs in Medicare and Non–Medicare Beneficiaries

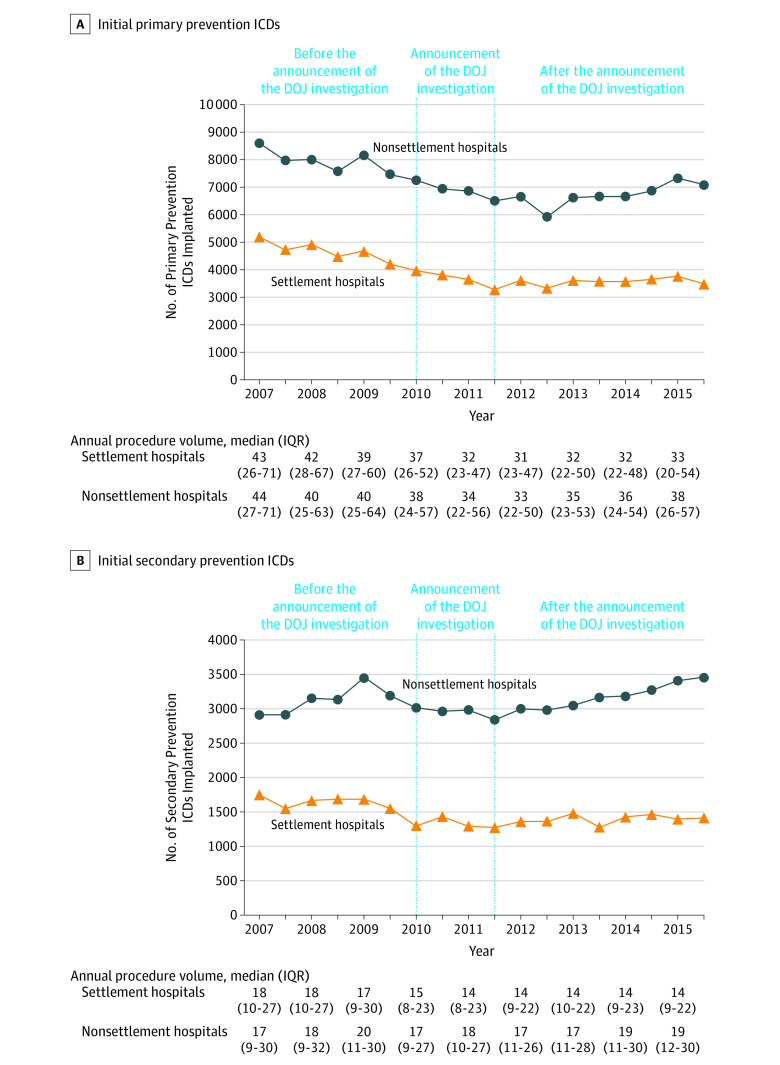

Trends in the volume of primary prevention ICDs for each 6-month interval is shown in Figure 3A. Overall, there were significant reductions in procedural volume across all hospitals with larger reductions at settlement hospitals. There was a 32.8% (95% CI, 29.9% to 35.7%) relative and 1703 (95% CI, 1520 to 1886) absolute reduction in primary prevention ICD implants at settlement hospitals compared with a 17.4% (95% CI, 14.8% to 20.0%) relative and 1495 (95% CI, 1249 to 1741) absolute decrease in primary prevention ICDs at nonsettlement hospitals (P < .001 for both; P for interaction < .001). The decrease in initial primary prevention ICD volume began before hospitals were made aware of the DOJ investigation and continued through June 2011 with relatively stable volume through the remainder of the study period. The volume of initial secondary prevention ICDs is shown in Figure 3B with a 19.1% (95% CI, 13.4% to 24.8%) relative and 334 (95% CI, 224 to 444) absolute decrease in secondary prevention ICDs at settlement hospitals and a 19.1% (95% CI, 13.2% to 25.0%) relative and 555 (95% CI, 399 to 711) absolute increase in secondary prevention ICDs at nonsettlement hospitals (Figure 3B). Among settlement hospitals, the decreases in secondary prevention ICDs began prior to the announcement of the investigation in 2010. Trends in the volume of primary prevention ICDs for non–Medicare beneficiaries are also similar to those for Medicare beneficiaries (eFigure 3 in the Supplement).

Figure 3. Volume of Primary and Secondary Prevention ICDs in Medicare Beneficiaries by Hospital DOJ Settlement Status at the Hospital Level.

DOJ indicates US Department of Justice; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; IQR, interquartile range. Volume of initial primary and secondary prevention ICDs at the hospital level in Medicare beneficiaries from January 1, 2007, through December 31, 2015, in 6-mo intervals at 180 hospitals that settled with the DOJ (settlement hospitals) and 325 hospitals that did not settle (nonsettlement hospitals). The model was designed to evaluate the 3 periods: before the DOJ investigation announcement (January 2007-December 2009); the DOJ investigation announcement (January 2010-June 2011); and after the DOJ investigation announcement (July 2011-December 2015). Hospitals were notified of the DOJ investigation as early as January 2010 with public announcement of the investigation by the Heart Rhythm Society in January 2011. The announcement period, January 2010 through June 2011, comprises the period when the investigation would have first impacted ICD utilization and patient selection. A, There was a −32.8% (95% CI, −35.7% to −29.9%) relative change and −1703 (95% CI, −1886 to −1520) absolute change in the volume of initial primary prevention ICDs at settlement hospitals compared with a −17.4% (95% CI, −20.0% to −14.8% ) relative change and −1495 (95% CI, −1741 to −1249) absolute change in volume at nonsettlement hospitals. B, There was a −19.1% (95% CI, −24.8% to −13.4%) relative change and −344 (95% CI, −444 to −244) absolute change in the volume of initial secondary prevention ICDs at settlement hospitals compared with a 19.1% (95% CI, 13.2% to 25.0%) relative change and 555 (95% CI, 399 to 711) absolute change in volume at nonsettlement hospitals.

The volume of ICD generator changes for the end of battery life or ICD device upgrades for Medicare beneficiaries for each 6-month period at continuously participating hospitals stratified by hospital settlement group is shown in eFigure 4 in the Supplement. In contrast to volume trends observed for primary prevention ICDs, the volume of these implants increased steadily in the period prior to the announcement of the DOJ investigation and remained relatively stable in the periods following the announcement. Moreover, the volume trends for ICD generator changes and device upgrades did not vary between hospital settlement groups.

Discussion

This national study of initial primary prevention ICDs from January 2007 through December 2015 demonstrates that the proportion of implants not meeting the CMS NCD criteria decreased at all hospitals following the announcement of the DOJ investigation, with larger and more rapid reductions at settlement hospitals, and the reduction also extended to non–Medicare beneficiaries, which were not the subject of the DOJ investigation. Over the study period, there were significant reductions in the volume of primary prevention ICDs with comparatively larger reductions at settlement hospitals. In contrast, the total volume of secondary prevention devices was relatively stable over the study period with the observed reductions in procedural volume at settlement hospitals offset by increases among nonsettlement hospitals.

The study interval spans a dynamic period for ICD utilization including evolving evidence and the DOJ investigation. Although concerns about potential overuse of ICDs were raised immediately following the release of the NCD criteria,10,22,23,24,25 this analysis demonstrates that the proportion of primary prevention ICDs not meeting the NCD criteria modestly decreased from January 2007 through December 2009. This trend was accompanied by reductions in primary prevention ICD implant volume prior to the announcement of the DOJ investigation and may reflect wider adoption of the NCD criteria and clinical practice guidelines, changes in the profile of patients at risk for sudden death, hospital participation in the ICD Registry, and other quality improvement initiatives. Following the announcement of the DOJ investigation, the reductions in the proportion of ICDs not meeting the NCD criteria were larger and more rapid, and extended to nonsettlement hospitals and to ICDs among non–Medicare beneficiaries potentially reflecting broad awareness of the investigation.

Despite substantial decreases in the proportion of primary prevention ICDs not meeting NCD criteria, there was persistent variation in performance at the hospital level with more than 14% of primary prevention ICDs not meeting NCD criteria at the worst-performing hospitals. Although this variation may represent opportunity for improvement, it may also reflect a gap between the NCD criteria and clinical practice. Current guidelines clarify that “the ultimate judgment about care of a particular patient must be made by the healthcare provider and patient in light of all the circumstances presented by that patient. As a result, situations may arise in which deviations from these guidelines may be appropriate.”8 To that point, the DOJ acknowledged that there are legitimate clinical indications for placing an ICD that does not meet current NCD guidelines in their lawsuit resolution model given to hospitals to evaluate liability. Furthermore, CMS has updated the NCD criteria on ICDs to reflect new clinical studies and practice guidelines.18,26,27,28,29 The need for concordance between the NCD criteria, practice guidelines, and appropriate use criteria has been the subject of ongoing discussions and warrants additional study.30

Understanding potential unintended consequences of the DOJ investigation remains an important area for further study. The analyses of secondary prevention ICDs do not suggest that access to necessary procedures was negatively affected by the investigation and observed changes in secondary prevention ICD volume preceded the announcement. These analyses offer some reassurance, but further research into hospital responses to the investigation could offer additional insights about possible unintended consequences.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, this analysis may not reflect all cases among non–Medicare beneficiaries as hospitals are only required to submit data on Medicare beneficiaries for reimbursement. Nonetheless, 80% of participating hospitals report all types of ICD implantations performed for any payer.10,31 Second, although hospitals were stratified by inclusion in DOJ settlements, there is no public listing identifying all hospitals that were officially investigated by the DOJ. The initial whistle-blower complaint included many more hospitals than the final list of facilities who ultimately reached settlements. As such, the group of hospitals that did not settle likely includes facilities that were investigated. Third, interrupted time series analysis attributes observed changes to the single factor of interest regardless of other simultaneous changes. Many factors likely influenced practice patterns over the study period, and we cannot be certain that the observed trends are a direct result of the DOJ investigation. Fourth, because we only have information about patients that actually received ICDs, we are unable to fully assess whether the DOJ investigation was associated with any barriers to the placement of clinically indicated ICDs.

Conclusions

From 2007 through 2015, the volume of primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and the proportion of devices not meeting the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services National Coverage Determination criteria decreased at all hospitals with substantially larger decreases at hospitals that reached settlements in the US Department of Justice investigation. These patterns extended to implantable cardioverter-defibrillators placed in non–Medicare beneficiaries, which were not the focus of the US Department of Justice investigation.

eTable. Hospital Characteristics Stratified by DOJ Settlement Status

eFigure 1. Timeline of Major Events in Development of CMS NCD for Primary Prevention ICDs and the DOJ Investigation

eFigure 2. Proportions of Initial Primary Prevention ICDs Implanted Outside the CMS NCD Guidelines in Medicare Beneficiaries at Six-Month Intervals, Stratified by DOJ Settlement Status at the Hospital Level

eFigure 3. Volume of Initial Primary Prevention ICDs Implanted in Non-Medicare Beneficiaries at Six-Month Intervals, Stratified by DOJ Settlement Status at the Hospital Level

eFigure 4. Volume of ICD Generator Changes or Device Upgrades in Medicare Beneficiaries at Six-Month Intervals, Stratified by DOJ Settlement Status at the Hospital Level

References

- 1.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, et al. ; Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial (SCD-HeFT) Investigators . Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(3):225-237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, et al. ; Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II Investigators . Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(12):877-883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadish A, Dyer A, Daubert JP, et al. ; Defibrillators in Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation (DEFINITE) Investigators . Prophylactic defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(21):2151-2158. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bigger JTJ Jr; Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) Patch Trial Investigators . Prophylactic use of implanted cardiac defibrillators in patients at high risk for ventricular arrhythmias after coronary-artery bypass graft surgery. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(22):1569-1575. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711273372201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hohnloser SH, Kuck KH, Dorian P, et al. ; DINAMIT Investigators . Prophylactic use of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(24):2481-2488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steinbeck G, Andresen D, Seidl K, et al. ; IRIS Investigators . Defibrillator implantation early after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(15):1427-1436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . National Coverage Determination (NCD) for implantable automatic defibrillators (20.4). https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/ncd-details.aspx?NCDId=110&ver=3. Published January 27, 2005. Accessed August 2, 2017.

- 8.Tracy CM, Epstein AE, Darbar D, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update of the 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(14):1297-1313. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kusumoto FM, Calkins H, Boehmer J, et al. HRS/ACC/AHA expert consensus statement on the use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in patients who are not included or not well represented in clinical trials. Circulation. 2014;130(1):94-125. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Khatib SM, Hellkamp A, Curtis J, et al. Non-evidence-based ICD implantations in the United States. JAMA. 2011;305(1):43-49. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.US Department of Justice . Nearly 500 hospitals pay United States more than $250 million to resolve false claims act allegations related to implantation of cardiac devices. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/nearly-500-hospitals-pay-united-states-more-250-million-resolve-false-claims-act-allegations. Published October 30, 2015. Accessed May 31, 2018.

- 12.US Department of Justice . Fifty-one hospitals pay United States more than $23 million to resolve false claims act allegations related to implantation of cardiac devices. United States Department of Justice. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/fifty-one-hospitals-pay-united-states-more-23-million-resolve-false-claims-act-allegations. Published February 17, 2016. Accessed August 31, 2017.

- 13.Schencker L. How DOJ got 500-plus hospitals to settle over cardiac implants. http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20160528/MAGAZINE/305289982. Accessed September 1, 2017.

- 14.Kremers MS, Hammill SC, Berul CI, et al. The National ICD Registry Report: version 2.1 including leads and pediatrics for years 2010 and 2011. Heart Rhythm. 2013;10(4):e59-e65. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2013.01.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Masoudi FA, Ponirakis A, de Lemos JA, et al. Trends in US cardiovascular care: 2016 report from 4 ACC National Cardiovascular Data Registries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(11):1427-1450. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of Cardiology . What each registry collects. https://cvquality.acc.org/NCDR-Home/Data-Collection/What-Each-Registry-Collects. Accessed September 4, 2017.

- 17.Messenger JC, Ho KKL, Young CH, et al. ; NCDR Science and Quality Oversight Committee Data Quality Workgroup . The National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) Data Quality Brief: the NCDR Data Quality Program in 2012. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(16):1484-1488. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cornish K, Kahan KB. DOJ implantable cardiac defibrillator investigation. https://www.navigant.com:443/experience/disputes-investigations/doj-icd-10-case-study. Published January 1, 2015. Accessed August 30, 2017.

- 19.Husten L. Heart Rhythm Society advising DOJ in investigation of ICD implants. http://www.cardiobrief.org/2011/01/21/heart-rhythm-society-advising-doj-in-investigation-of-icd-implants/. Published January 21, 2011. Accessed May 31, 2018.

- 20.Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(6)(suppl):S38-S44. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2013.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner AK, Soumerai SB, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27(4):299-309. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00430.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClellan MB, Tunis SR. Medicare coverage of ICDs. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(3):222-224. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tung R, Zimetbaum P, Josephson ME. A critical appraisal of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy for the prevention of sudden cardiac death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(14):1111-1121. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsai V, Goldstein MK, Hsia HH, Wang Y, Curtis J, Heidenreich PA; National Cardiovascular Data Registry . Age differences in primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator use in US individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(9):1589-1595. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03542.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matlock DD, Peterson PN, Heidenreich PA, et al. Regional variation in the use of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for primary prevention: results from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(1):114-121. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.110.958264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carlson J. Feds notify hospitals of liability for wrongly implanted heart devices. http://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20120830/NEWS/308309943. Published August 30, 2012. Accessed September 5, 2017.

- 27.American College of Cardiology . ACC comments on Medicare coverage for ICDs. http://www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2017/06/29/12/43/acc-comments-on-medicare-coverage-for-icds. Accessed November 1, 2017.

- 28.Masoudi FM, Oetgen WJ. The NCDR ICD Registry: a foundation for quality improvement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(13):1673-1674. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen TS, Chin J, Ashby L, Dolan D, Caños D, Hutter J. Proposed decision memo for implantable cardioverter defibrillators (CAG-00157R4). https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-proposed-decision-memo.aspx?NCAId=288. Accessed December 11, 2017.

- 30.Fogel RI, Epstein AE, Mark Estes NA III, et al. The disconnect between the guidelines, the appropriate use criteria, and reimbursement coverage decisions: the ultimate dilemma. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(1):12-14. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.American College of Cardiology . Hospital registries. https://cvquality.acc.org/NCDR-Home/Registries/Hospital-Registries. Accessed August 2, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Hospital Characteristics Stratified by DOJ Settlement Status

eFigure 1. Timeline of Major Events in Development of CMS NCD for Primary Prevention ICDs and the DOJ Investigation

eFigure 2. Proportions of Initial Primary Prevention ICDs Implanted Outside the CMS NCD Guidelines in Medicare Beneficiaries at Six-Month Intervals, Stratified by DOJ Settlement Status at the Hospital Level

eFigure 3. Volume of Initial Primary Prevention ICDs Implanted in Non-Medicare Beneficiaries at Six-Month Intervals, Stratified by DOJ Settlement Status at the Hospital Level

eFigure 4. Volume of ICD Generator Changes or Device Upgrades in Medicare Beneficiaries at Six-Month Intervals, Stratified by DOJ Settlement Status at the Hospital Level