Key Points

Question

Are comorbidities or epilepsy types associated with the selection of antiepileptic drugs in women with epilepsy of childbearing age?

Findings

In a cohort study of 46 767 women of childbearing age with epilepsy, valproate sodium and phenytoin sodium were more commonly used for generalized epilepsy; oxcarbazepine was more often used for focal epilepsy. Valproate and topiramate were more likely prescribed in women with comorbid headache or migraine; valproate was more likely prescribed in women with comorbid psychiatric comorbidities.

Meaning

Many women appear to receive valproate, topiramate, and phenytoin despite known teratogenicity risks; to improve current practice, teratogenicity risk awareness should be increased among women of childbearing age with epilepsy and other medical conditions, and among physicians.

Abstract

Importance

Limited population-based data are available on antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment patterns in women of childbearing age with epilepsy; the current population risk is not clear.

Objectives

To examine the AED treatment patterns and identify differences in use of valproate sodium and topiramate by comorbidities among women of childbearing age with epilepsy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A retrospective cohort study used a nationwide commercial database and supplemental Medicare as well as Medicaid insurance claims data to identify 46 767 women with epilepsy aged 15 to 44 years. The eligible study cohort was enrolled between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013. Data analysis was conducted from January 1, 2017, to February 22, 2018.

Exposures

Cases required an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification–coded epilepsy diagnosis with continuous medical and pharmacy enrollment. Incident cases required a baseline of 2 or more years without an epilepsy diagnosis or AED prescription before the index date. For both incident and prevalent cases, focal and generalized epilepsy cohorts were matched by age, payer type, and enrollment period and then compared.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Antiepileptic drug treatment pattern according to seizure type and comorbidities.

Results

Of the 46 767 patients identified, there were 8003 incident cases (mean [SD] age, 27.3 [9.4] years) and 38 764 prevalent cases (mean [SD] age, 29.7 [9.0] years). Among 3219 women in the incident epilepsy group who received AEDs for 90 days or more, 3173 (98.6%) received monotherapy as first-line treatment; among 28 239 treated prevalent cases, 18 987 (67.2%) received monotherapy. In 3544 (44.3%) incident cases and 9480 (24.5%) prevalent cases, AED treatment was not documented during 180 days or more of follow-up after diagnosis. Valproate (incident: 35 [5.81%]; prevalent: 514 [13.1%]) and phenytoin (incident: 33 [5.48%]; prevalent: 178 [4.53%]) were more commonly used for generalized epilepsy and oxcarbazepine (incident: 53 [8.03%]; prevalent: 386 [9.89%]) was more often used for focal epilepsy. Levetiracetam (incident: focal, 267 [40.5%]; generalized, 271 [45.0%]; prevalent: focal, 794 [20.3%]; generalized, 871 [22.2%]), lamotrigine (incident: focal, 123 [18.6%]; generalized, 106 [17.6%]; prevalent: focal, 968 [24.8%]; generalized, 871 [22.2%]), and topiramate (incident: focal, 102 [15.5%]; generalized, 64 [10.6%]; prevalent: focal, 499 [12.8%]; generalized, 470 [12.0%]) were leading AEDs prescribed for both focal and generalized epilepsy. Valproate was more commonly prescribed for women with comorbid headache or migraine (incident: 53 of 1251 [4.2%]; prevalent: 839 of 8046 [10.4%]), mood disorder (incident: 63 of 860 [7.3%]; prevalent: 1110 of 6995 [15.9%]), and anxiety and dissociative disorders (incident: 57 of 881 [6.5%]; prevalent: 798 of 5912 [13.5%]). Topiramate was more likely prescribed for those with comorbid headache or migraine (incident: 335 of 1251 [26.8%]; prevalent: 2322 of 8046 [28.9%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

Many women appear to be treated with valproate and topiramate despite known teratogenicity risks. Comorbidities may affect selecting certain AEDs despite their teratogenicity risks.

This cohort study examines the use of antiepileptic drugs and differences between valproate and topiramate prescribing in women of childbearing age with epilepsy.

Introduction

Children exposed to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) during the fetal period have an increased risk of congenital malformations.1,2 Congenital malformations associated with fetal AED exposure are classified as anatomic teratogenicity, whereas cognitive or behavioral deficits are classified as behavioral teratogenicity.3 Anatomic teratogenicity includes cardiac malformations; orofacial clefts; and skeletal, urologic, and neural tube defects. Teratogenicity risk is higher with the use of valproate sodium, phenobarbital sodium, phenytoin sodium, carbamazepine, and topiramate monotherapy as well as AED polytherapy.3,4

Among these AEDs, topiramate use in early pregnancy was reported in 2008 to be associated with a higher risk of cleft palate,5,6 with a greater risk at increased doses (>100 mg/d) confirmed in 2018.7 Fetal exposure to topiramate has also been associated with small-for-gestational-age newborns.8 Valproate appears to be associated with behavioral teratogenicity, such as impaired cognitive function and autism spectrum disorder,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 as well as anatomic teratogenicity.18,19 An increased risk of impaired cognitive function from fetal exposure to valproate was first reported by the Neurodevelopmental Effects of Antiepileptic Drugs (NEAD) study in 2009.17 In 2013, the US Food and Drug Administration13 changed valproate’s pregnancy category for migraine from D (the potential benefit of the drug in pregnant women may be acceptable despite its potential risks) to X (the risk of use in pregnant women clearly outweighs any possible benefit of the drug based on the evidence).17 Although valproate remains in pregnancy category D for treating epilepsy and bipolar disorder, use of valproate products is recommended only if other medications are ineffective or not tolerated.20 Valproate prescribing is currently banned for women who are not part of a pregnancy prevention program in the United Kingdom.21

There is evidence that AED treatment patterns have changed, as valproate use has decreased and been replaced by lamotrigine and levetiracetam in women of childbearing age and during pregnancy.22,23,24 Low doses of lamotrigine, levetiracetam, and oxcarbazepine as monotherapy have been reported to be associated with the least risk of major malformations in the offspring,4,19,25,26 although the neurodevelopmental effect of oxcarbazepine is not fully understood. Lamotrigine and levetiracetam are recommended for women with epilepsy of childbearing age.27 Most data on the use of AEDs in women of childbearing age have been obtained from registries.19,24,25 These registry data might not be fully representative of the general population.

There are few population-based studies on the treatment patterns for AEDs in women of childbearing age with epilepsy.23,28,29,30 Our study aimed to examine AED treatment patterns during 180 or more days of follow-up after the index date and identify differences in use of valproate and topiramate by comorbidities among women of childbearing age with epilepsy.

Methods

Study Design and Data Sources

We conducted a retrospective cohort study in women of childbearing age (15-44 years) enrolled between January 1, 2009, and December 31, 2013, in the Truven Health MarketScan commercial and supplemental Medicare (CCMC) and Medicaid insurance claims databases, which consist of data from across the United States. The pooled databases contain over 100 million covered lives per year. The CCMC database comprises privately insured individuals in all 50 states and Washington, DC, under a variety of commercial insurance plans. The Medicaid database comprises individuals from 13 geographically dispersed states. The combined CCMC and Medicaid databases are designed to broadly represent health care practice in the insured population of the United States. These recent data contrast with earlier data describing AED prescribing practices in women of childbearing age, such as those used in the NEAD study,16,22 which were derived from a smaller multicenter study population from the United States and United Kingdom.

The databases capture information on inpatient, outpatient, and emergency medical care, and pharmacy claims. The information includes date and place of service, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis, and dispensed medications, as well as information on age, sex, health insurance payer type, and monthly enrollment status. These files are linkable by encrypted patient identification numbers.

All data are compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The Emory University Institutional Review Board determined the study was exempt.

Inclusion Criteria and Case Identification

Epilepsy cases were defined consistent with guidelines of the International League Against Epilepsy Epidemiology Commission31 and a computer algorithm developed for detecting epilepsy cases.32 Using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes and AED claims, we identified a case of epilepsy if it met any of the following criteria: (1) an occurrence of 2 or more ICD-9-CM codes 345.xx among separate medical encounters on separate dates, (2) an occurrence of 1 or more ICD-9-CM codes 345.xx and 1 or more ICD-9-CM codes 780.39 among separate medical encounters on separate dates, (3) an occurrence of 1 ICD-9-CM code 345.xx and 1 or more codes for AED prescription, and (4) an occurrence of 2 or more ICD-9-CM codes 780.39 among separate medical encounters on separate dates and 1 or more codes for AED prescription.33 For definitions requiring 2 or more ICD-9-CM codes, the first code occurrence defined the index date. Incident cases had an index date between January 1, 2011, and June 30, 2013, and a prior baseline of 2 or more years without an epilepsy diagnosis or AED prescription. Prevalent cases had an index date between January 1, 2010, and June 30, 2013, and a prior 1-year baseline with an epilepsy diagnosis. Incident cases and prevalent cases were mutually exclusive.

Focal epilepsy was defined using ICD-9-CM codes 345.4x, 345.5x, or 345.7 × and generalized epilepsy was defined using ICD-9-CM codes 345.0x, 345.1x, or 345.2 at index date. Undefined epilepsy comprised nonspecific codes (345.3x, 345.6x, 345.8x, 345.9x, and 780.39) or inconsistent cases (with both focal and generalized codes). The focal and generalized epilepsy cohorts were matched by age, payer type, and enrollment period. Antiepileptic drug treatment patterns during the follow-up period were examined. Follow-up started at the index date and continued to the end of the study period or end of enrollment. The minimum follow-up duration was 180 days.

The AED treatment lines were assessed from time of diagnosis to the end of the follow-up period for each incident patient. Treatment was classified as monotherapy and polytherapy. A treatment line was defined by the addition or substitution of an AED. Classification as monotherapy or polytherapy in incident cases was based on the first (initial) line of treatment. Thus, patients who began monotherapy and were later treated concurrently with more than 1 AED were still listed in the monotherapy category. Monotherapy was defined as the presence of a pharmacy claim for 1 AED for at least 90 days without a prescription of another AED. Polytherapy was defined as the presence of pharmacy claims for 2 or more AEDS prescribed concurrently for at least 90 days. Patients with an AED prescription of less than 90 days were not classified as receiving either monotherapy or polytherapy.

Comorbidities Identification

Comorbidities were identified using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes occurring on or after the index dates for epilepsy. The comorbidities included mood disorder (293.83, 296.xx, 311), anxiety and dissociative disorders (293.84, 300.xx, 308.xx), and headache and migraine (784.0, 307.81, 339.xx, 346.xx).

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported as means (SDs), median and quartiles or range for continuous variables, and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. To compare 2 groups, χ2 tests were used. Significance level was set at α = .05 with a 2-tailed test. Data analysis was conducted from January 1, 2017, to February 22, 2018, using SAS, version 9.3, software (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Patient Characteristics

A total of 46 767 women with epilepsy of childbearing age (15-44 years) were identified. The women were distributed grouped according to these intervals of follow-up: 180 to 364 days (14 217 [30.5%]), 365 to 729 days (19 876 [42.5%]), and 730 days or longer (12 674 [27.1%]).

Incident Cases

We identified 8003 incident cases (Table 1). The mean (SD) age was 27.3 (9.4) years and 6038 women (75.4%) were enrolled for CCMC benefits. Epilepsy diagnosis was classified as focal (1587 [19.8%]), generalized (2033 [25.4%]), and undefined (4383 [54.8%]). The most common comorbidity was headache or migraine (2163 [27.0%]). The common psychiatric comorbidities included anxiety and dissociative disorder (1570 [19.6%]) and mood disorders (1472 [18.4%]).

Table 1. Age and Payer Type Among Women With Incident and Prevalent Epilepsy.

| Variable | No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incident Epilepsy | Prevalent Epilepsy | |||||

| Overall (n = 8003) | Focal (n = 1587) | Generalized (n = 2033) | Overall (n = 38 764) | Focal (n = 8081) | Generalized (n = 9128) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 27.3 (9.4) | 27.8 (9.7) | 26.7 (9.4) | 29.7 (9.0) | 29.8 (9.2) | 28.8 (9.0) |

| 15-19 | 2440 (30.5) | 479 (30.2) | 676 (33.3) | 7268 (18.7) | 1568 (19.4) | 1957 (21.4) |

| 20-24 | 1400 (17.5) | 257 (16.2) | 359 (17.7) | 6260 (16.1) | 1273 (15.8) | 1564 (17.1) |

| 25-34 | 1844 (23.0) | 358 (22.6) | 448 (22.0) | 11 394 (29.4) | 2240 (27.7) | 2678 (29.3) |

| 35-44 | 2319 (29.0) | 493 (31.1) | 550 (27.1) | 13 842 (35.7) | 3000 (37.1) | 2929 (32.1) |

| Payer type, No. (%) | ||||||

| Commercial/Medicare | 6038 (75.4) | 1306 (82.3) | 1568 (77.1) | 25 038 (64.6) | 5995 (74.2) | 6033 (66.1) |

| Medicaid | 1965 (24.6) | 281 (17.7) | 465 (22.9) | 13 726 (35.4) | 2086 (25.8) | 3095 (33.9) |

| Treatment, No. | 881c | 806c | 6052d | 5818d | ||

| No AED | 3544 (44.3) | NA | NA | 9480 (24.5) | NA | NA |

| AEDa | 3219 (40.2) | 666 (75.6) | 604 (74.9) | 28,239 (72.8) | 5846 (96.6) | 5623 |

| Monotherapy | 3173 (98.6) | 660 (99.1) | 602 (99.7) | 18 987 (67.2) | 3904 (66.8) | 3932 (69.9) |

| Polytherapy | 46 (1.4) | 6 (0.9) | 2 (0.3) | 9252 (32.8) | 1942 (33.2) | 1691 (30.1) |

| Not classifiedb | 1240 (15.5) | 215 (24.4) | 202 (25.1) | 1045 (2.7) | 206 (3.4) | (3.4) |

Abbreviations: AED, antiepileptic drug; NA, not applicable.

An AED prescription of 90 days and more.

An AED prescription of less than 90 days; under the table.

Matched in incident cases. Incident cases reflect first-line treatment.

Matched prevalent cases.

Prevalent Cases

A total of 38 764 prevalent cases were identified (Table 1). The mean age was 29.7 (9.0) years and 25 038 women (64.6%) were enrolled for CCMC benefits. Epilepsy diagnosis was classified as focal (8081 [20.8%]), generalized (9128 [23.5%]), and undefined (21 555 [55.6%]). The most common comorbidity was headache or migraine (12 180 [31.4%]). The common psychiatric comorbidities included mood disorders (10 316 [26.6%]) and anxiety and dissociative disorder (9063 [23.4%]).

Monotherapy vs Polytherapy

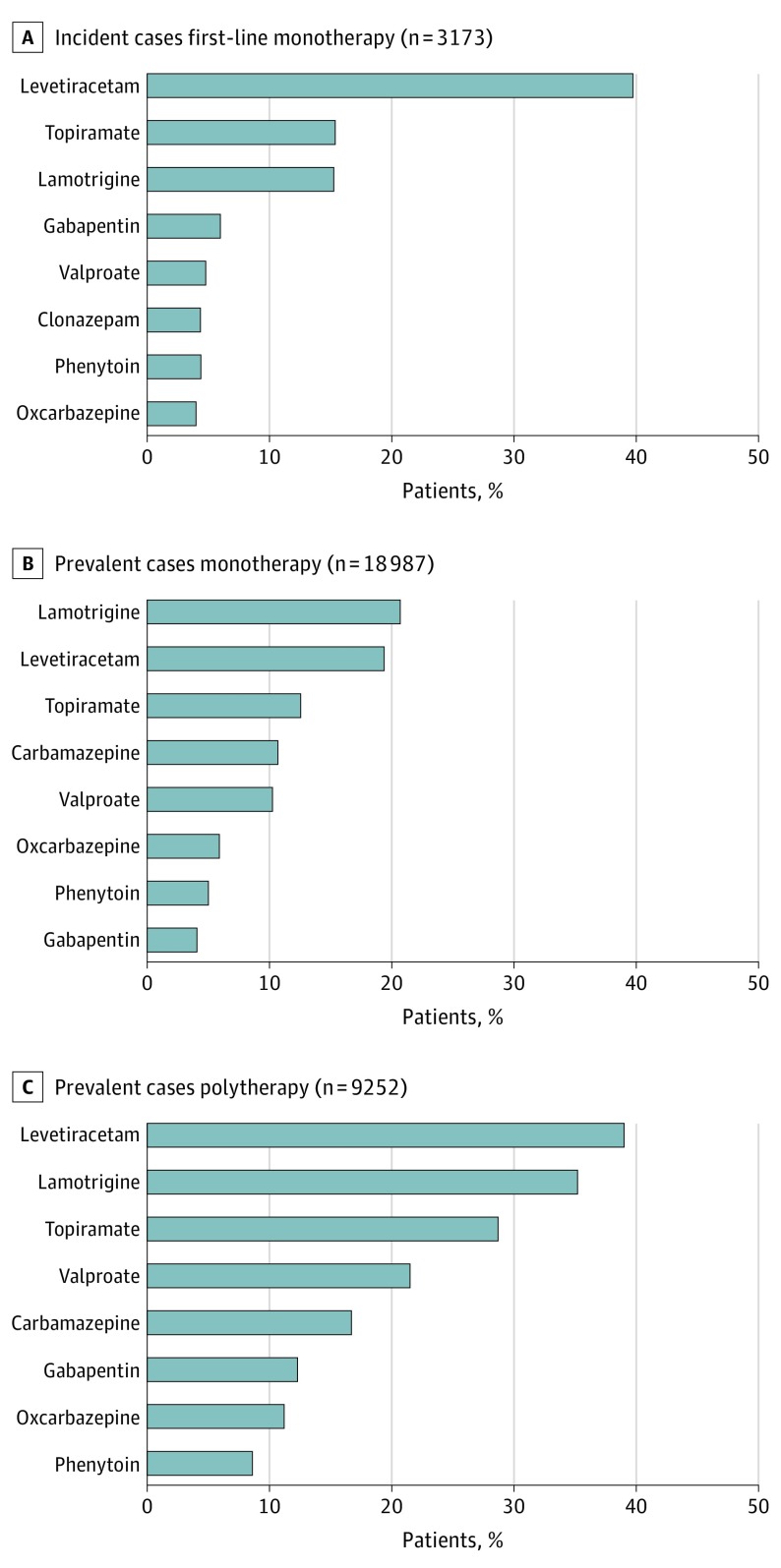

The overall number of AED treatment lines for incident cases were 0 (3544 [44.3%]), 1 (4459 [55.7%]), 2 (1107 [24.8%]), 3 (794 [9.9%]), and 4 or more (264 [3.3%]). Of the 3219 incident patients receiving AED treatment for 90 days or more, 3173 (98.6%) received monotherapy and 46 (1.4%) received polytherapy as first-line treatment (Table 1). Among incident cases receiving monotherapy, the most commonly prescribed AEDs as first-line treatment were levetiracetam (1259 [39.7%]), topiramate (489 [15.4%]), and lamotrigine (485 [15.3%]) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Antiepileptic Drug Treatment Among Incident and Prevalent Cases.

For 28 239 women in the prevalent group receiving AED treatment for 90 or more days, 18 987 (67.2%) were treated with monotherapy and 9252 (32.8%) received polytherapy (Table 1). Among patients with prevalent epilepsy receiving monotherapy, the most frequently prescribed AEDs were lamotrigine (3931 [20.7%]), levetiracetam (3684 [19.4%]), topiramate (2383 [12.6%]), carbamazepine (2026 [10.7%]), and valproate (1945 [10.2%]) (Figure 1B). Among patients in the prevalent group receiving polytherapy, the leading AEDs were levetiracetam (3608 [39.0%]), lamotrigine (3257 [35.2%]), topiramate (2655 [28.7%]), and valproate (1989 [21.5%]) (Figure 1C).

Valproate was prescribed as first-line treatment (204 [4.6%]) for incident cases as well as monotherapy (1945 [10.2%]) and polytherapy (1988 [21.5%]) for prevalent cases (Table 2). Topiramate was prescribed as first-line treatment (663 [14.9%]) for incident cases as well as monotherapy (2383 [12.6%]) and polytherapy (2656 [28.7%]) for prevalent cases (Table 3).

Table 2. Use of Valproate Sodium Among AED-Treated Incident and Prevalent Patients With Comorbidities.

| Variable | All, No. (%) | Headache and Migraine, No. (%) | P Value | Mood Disorder, No. (%) | P Value | Anxiety and Dissociative Disorder, No. (%) | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With | Without | With | Without | With | Without | |||||

| Incident cases | ||||||||||

| Overall | 4459 | 1251 (28.1) | 3208 (71.9) | 860 (19.3) | 3599 (80.7) | 881 (19.8) | 3578 (80.2) | |||

| First-line treatment with valproate | 204 (4.6) | 53 (26.0) | 151 (74.0) | .55 | 63 (30.9) | 141 (69.1) | <.001 | 57 (27.9) | 147 (72.1) | .004 |

| First-line treatment without valproate | 4255 (95.4) | 1198 (28.2) | 3057 (71.8) | 797 (18.7) | 3458 (81.3) | 824 (19.4) | 3431 (80.6) | |||

| Prevalent cases | ||||||||||

| Monotherapy overall | 18 987 | 5342 (28.1) | 13 645 (71.9) | 4413 (23.2) | 14 574 (76.8) | 3774 (19.9) | 15 213 (80.1) | |||

| Monotherapy with valproate | 1945 (10.2) | 416 (21.4) | 1529 (78.6) | <.001 | 575 (29.6) | 1370 (70.4) | <.001 | 379 (19.5) | 1566 (80.5) | .67 |

| Monotherapy without valproate | 17 042 (89.8) | 4926 (28.9) | 12 116 (71.1) | 3838 (22.5) | 13 204 (77.5) | 3395 (19.9) | 13 647 (80.1) | |||

| Prevalent cases | ||||||||||

| Polytherapy overall | 9252 | 2704 (29.2) | 6548 (70.8) | 2582 (27.9) | 6670 (72.1) | 2138 (23.1) | 7114 (76.9) | |||

| Polytherapy with valproate | 1988 (21.5) | 423 (21.3) | 1565 (78.7) | <.001 | 535 (26.9) | 1453 (73.1) | .28 | 419 (21.1) | 1569 (78.9) | .02 |

| Polytherapy without valproate | 7264 (78.5) | 2281 (31.4) | 4983 (68.6) | 2047 (28.2) | 5217 (71.8) | 1719 (23.7) | 5545 (76.3) | |||

Abbreviation: AED, antiepileptic drug.

Table 3. Use of Topiramate Among AED-Treated Patients With Comorbidities.

| Variable | All, No. (%) | Headache or Migraine, No. (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | |||

| Incident cases | ||||

| Overall | 4459 | 1251 (28.1) | 3208 (71.9) | <.001 |

| First-line treatment with topiramate | 663 (14.9) | 335 (50.5) | 328 (49.5) | |

| First-line treatment without topiramate | 3796 (85.1) | 916 (24.1) | 2880 (75.9) | |

| Prevalent cases | ||||

| Monotherapy overall | 18 987 | 5342 (28.1) | 13 645 (71.9) | <.001 |

| Monotherapy with topiramate | 2383 (12.6) | 1275 (53.5) | 1108 (46.5) | |

| Monotherapy without topiramate | 16 604 (87.4) | 4067 (24.5) | 12 537 (75.5) | |

| Prevalent cases | ||||

| Polytherapy overall | 9252 | 2704 (29.2) | 6548 (70.8) | <.001 |

| Polytherapy with topiramate | 2656 (28.7) | 1047 (39.4) | 1609 (60.6) | |

| Polytherapy without topiramate | 6596 (71.3) | 1657 (25.1) | 4939 (74.9) | |

Abbreviation: AED, antiepileptic drug.

Focal vs Generalized Epilepsy

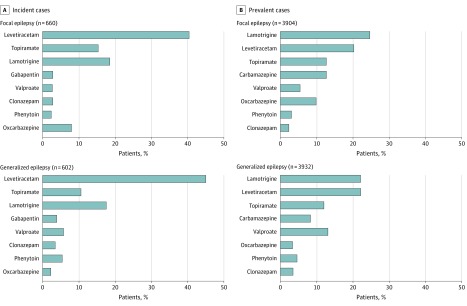

For the matched focal and generalized epilepsy cohorts, in both incident and prevalent cases, levetiracetam, lamotrigine, and topiramate were most often prescribed as monotherapy. Valproate (incident: 35 [5.81%]; prevalent: 514 [13.1%]) and phenytoin (incident: 33 [5.48%]; prevalent: 178 [4.53%]) were more commonly used for generalized epilepsy and oxcarbazepine (incident: 53 [8.03%]; prevalent: 386 [9.89%]) was more often used for focal epilepsy (all P < .05). Levetiracetam (incident: focal, 267 [40.5%]; generalized, 271 [45.0%]; prevalent: focal, 794 [20.3%]; generalized, 871 [22.2%]), lamotrigine (incident: focal, 123 [18.6%]; generalized, 106 [17.6%]; prevalent: focal, 968 [24.8%]; generalized, 871 [22.2%]), and topiramate (incident: focal, 102 [15.5%]; generalized, 64 [10.6%]; prevalent: focal, 499 [12.8%]; generalized, 470 [12.0%]) were leading AEDs prescribed for both focal and generalized epilepsy (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Antiepileptic Drug Treatment According to Seizure Type.

Comorbidity and Valproate

Valproate was more likely prescribed for women in the prevalent case group with comorbid headache or migraine as both monotherapy (416 [7.8%]; P < .001) and polytherapy (423 [15.6%]; P < .001). Valproate was more often prescribed as monotherapy for patients in both the incident (53 [7.3%]; P < .001) and prevalent (575 [13.0%]; P < .001) groups with comorbid mood disorder. Women with comorbid anxiety and/or dissociative disorders used valproate more frequently as first-line monotherapy in incident cases (57 [6.5%]; P = .004) and as polytherapy in prevalent cases (419 [19.6]; P = .02) (Table 2).

Headache and Topiramate

Topiramate was more often prescribed for patients in the incident group with comorbid headache or migraine (335 [26.8%]; P < .001). Women in the prevalent group with comorbid headache or migraine more likely received topiramate as monotherapy (1275 [23.9%]; P < .001) and polytherapy (1047 [38.7%]; P < .001) (Table 3).

Discussion

This population-based, observational, longitudinal cohort study using a nationally representative claims database provides insight into the current state of AED treatment and population risk for women with epilepsy of childbearing age. We found that most women of childbearing age with a new epilepsy diagnosis received monotherapy as first-line treatment, which is compatible with the guideline for first-line monotherapy.34 Regardless of seizure types, the most commonly prescribed AEDs were levetiracetam, lamotrigine, and topiramate for both incident and prevalent cases. These findings are in agreement with recent evidence that AED prescribing patterns have changed: valproate use has decreased and lamotrigine and levetiracetam use has increased for women of childbearing age, including during pregnancy.22,23

Given earlier reports of anatomic and behavioral teratogenicity associated with valproate, as well as recommendations in 2009 for pregnant women to avoid its use where possible,18 low rates of valproate use among women of reproductive age during most of the interval of our study might be expected. Although the magnitude of risk and range of adverse reproductive outcomes associated with topiramate use appear substantially less than those associated with valproate, some reduction in the use of topiramate in this population might be expected after evidence emerged in 2008 of its association with cleft palate.5 However, we found that a noticeable proportion of women in our population were treated with valproate and topiramate. Valproate was prescribed even for incident cases with focal epilepsy as the first-line monotherapy, and also more frequently for prevalent cases as either monotherapy or polytherapy regardless of seizure type. Topiramate was 1 of the top 3 AEDs in both incident and prevalent cases regardless of seizure types. To explore the reasons why valproate and topiramate are prescribed for women with epilepsy of childbearing age, we examined the difference in the use of these AEDs by the common comorbidities of psychiatric disorders and headache or migraine. Many AEDs are indicated for other conditions, such as neuropathic pain syndromes, migraine, and psychiatric disorder including anxiety, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder.29,35,36,37,38 Valproate has been used for nonepileptic indications, such as psychiatric disorders and headache or migraine. Topiramate is also indicated for migraine prophylaxis. We found that valproate was more frequently prescribed for those with comorbid mood or anxiety and dissociative disorder, and topiramate was more likely prescribed for women with comorbid headache or migraine compared with those without comorbidities.

Comorbidities could affect the selection of AEDs despite their teratogenicity risks.37 This finding is similar to an earlier study in that valproate prescriptions have declined for epilepsy but not for other conditions in women of childbearing age.23 To improve current practice, knowledge of the teratogenicity of certain AEDs should be disseminated to health care professionals and patients. Additional education is needed to increase the awareness of the teratogenicity risks and women should participate in AED selection based on comprehensive information.39,40 The efficacy of the medical and patient information program can be assessed by monitoring AED prescription patterns in a population-based cohort.

Limitations

This study has limitations. First, there are intrinsic shortfalls of claims data, such as the potential for misclassification of cases because of coding errors or incorrect diagnoses. To improve diagnostic accuracy using these data, we considered both the number of occurrences of ICD-9-CM diagnostic code entries and their conjunction with dispensed AED national drug code data for case identification.31,41,42 However, our criteria probably include women who had nonepileptic events, such as psychogenic seizures, but received an AED prescription. Second, in this cohort, a significant proportion of incident cases were found not to have any AED treatment documentation. Further research is warranted to explain this finding. Third, we compared the use of certain AEDs between women with and without comorbidities using χ2 tests. We suspect that many patients have multiple comorbidities. To evaluate the association of each comorbid condition with use of the drugs, a regression analysis may be best to avoid potential confounding effects.

Fourth, some of the women who were treated with valproate may not have been at risk for pregnancy because they were using reliable birth control methods, including oral contraceptives; were not planning a pregnancy; or were biologically incapable of becoming pregnant. Nevertheless, a previous study reported that more than half of pregnancies in women with epilepsy were unintended.43 The Epilepsy Birth Control Registry web-based survey found that only 69.7% of women with epilepsy at risk of unintended pregnancy were using contraception methods.44 Fifth, we did not investigate the use of folic acid. Folic acid deficiency during early pregnancy is associated with the risks of major congenital malformations, such as neural tube defect, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends folic acid supplementation during pregnancy.45 However, only 40% of women of childbearing age reported taking a folic acid supplement46 and 47.6% of the women with epilepsy at risk of unintended pregnancy reported taking folic acid supplement.47 Sixth, the study covered the period from 2009 to 2013 and therefore we were not able to measure the association between the change in the US Food and Drug Administration labeling for valproate and the prescription patterns for valproate in this patient population. Seventh, we were unable to identify which physicians were prescribing valproate to incident patients or whether there were regional prescribing differences.

Conclusions

This population-based longitudinal cohort study suggests that a noticeable proportion of women were treated with valproate and topiramate despite known teratogenicity risks. Comorbidities may be likely to affect selecting certain AEDs despite their teratogenicity risks. This finding suggests that physicians and women of childbearing age with epilepsy should be aware of and sensitive to teratogenicity risks of certain AEDs. In addition, efforts to raise awareness of current American Academy of Neurology quality measures on the counseling of teratogenicity risk may assist in ensuring that the risk-benefit profiles of treatments are evaluated by both clinicians and patients.48 Treatment patterns for women of childbearing age with epilepsy should continue to be monitored through population-based studies.

References

- 1.Tomson T, Battino D. Teratogenic effects of antiepileptic drugs. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(9):803-813. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70103-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arpino C, Brescianini S, Robert E, et al. Teratogenic effects of antiepileptic drugs: use of an International Database on Malformations and Drug Exposure (MADRE). Epilepsia. 2000;41(11):1436-1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.2000.tb00119.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meador KJ, Loring DW. Developmental effects of antiepileptic drugs and the need for improved regulations. Neurology. 2016;86(3):297-306. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al. ; EURAP Study Group . Comparative risk of major congenital malformations with eight different antiepileptic drugs: a prospective cohort study of the EURAP registry. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(6):530-538. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30107-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunt S, Russell A, Smithson WH, et al. ; UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register . Topiramate in pregnancy: preliminary experience from the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register. Neurology. 2008;71(4):272-276. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000318293.28278.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Margulis AV, Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, et al. ; National Birth Defects Prevention Study . Use of topiramate in pregnancy and risk of oral clefts. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(5):405.e1-405.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernandez-Diaz S, Huybrechts KF, Desai RJ, et al. Topiramate use early in pregnancy and the risk of oral clefts: a pregnancy cohort study. Neurology. 2018;90(4):e342-e351. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernández-Díaz S, Mittendorf R, Smith CR, Hauser WA, Yerby M, Holmes LB; North American Antiepileptic Drug Pregnancy Registry . Association between topiramate and zonisamide use during pregnancy and low birth weight. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(1):21-28. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen J, Grønborg TK, Sørensen MJ, et al. Prenatal valproate exposure and risk of autism spectrum disorders and childhood autism. JAMA. 2013;309(16):1696-1703. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inoyama K, Meador KJ. Cognitive outcomes of prenatal antiepileptic drug exposure. Epilepsy Res. 2015;114:89-97. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker GA, Bromley RL, Briggs M, et al. ; Liverpool and Manchester Neurodevelopment Group . IQ at 6 years after in utero exposure to antiepileptic drugs: a controlled cohort study. Neurology. 2015;84(4):382-390. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bromley RL, Leeman BA, Baker GA, Meador KJ. Cognitive and neurodevelopmental effects of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22(1):9-16. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. ; NEAD Study Group . Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure and cognitive outcomes at age 6 years (NEAD study): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(3):244-252. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70323-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. ; NEAD Study Group . Effects of fetal antiepileptic drug exposure: outcomes at age 4.5 years. Neurology. 2012;78(16):1207-1214. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318250d824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. ; NEAD Study Group . Foetal antiepileptic drug exposure and verbal versus non-verbal abilities at three years of age. Brain. 2011;134(pt 2):396-404. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen MJ, Meador KJ, Browning N, et al. Fetal antiepileptic drug exposure: motor, adaptive, and emotional/behavioral functioning at age 3 years. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;22(2):240-246. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meador KJ, Baker GA, Browning N, et al. ; NEAD Study Group . Cognitive function at 3 years of age after fetal exposure to antiepileptic drugs. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(16):1597-1605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harden CL, Meador KJ, Pennell PB, et al. ; American Academy of Neurology; American Epilepsy Society . Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy—focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): teratogenesis and perinatal outcomes: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009;73(2):133-141. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a6b312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al. ; EURAP Study Group . Dose-dependent teratogenicity of valproate in mono- and polytherapy: an observational study. Neurology. 2015;85(10):866-872. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.US Food and Drug Administration FDA drug safety communication: valproate anti-seizure products contraindicated for migraine prevention in pregnant women due to decreased IQ scores in exposed children. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm350684.htm. Updated February 26, 2016. Accessed October 15, 2018.

- 21.Gov.UK Valproate use by women and girls. 2018; https://www.gov.uk/guidance/valproate-use-by-women-and-girls#toolkit. Updated December 18, 2018. Accessed October 15, 2018.

- 22.Meador KJ, Penovich P, Baker GA, et al. ; NEAD Study Group . Antiepileptic drug use in women of childbearing age. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;15(3):339-343. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wen X, Meador KJ, Hartzema A. Antiepileptic drug use by pregnant women enrolled in Florida Medicaid. Neurology. 2015;84(9):944-950. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meador KJ, Pennell PB, May RC, et al. ; MONEAD Investigator Group . Changes in antiepileptic drug-prescribing patterns in pregnant women with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2018;84:10-14. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2018.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, et al. ; EURAP study group . Dose-dependent risk of malformations with antiepileptic drugs: an analysis of data from the EURAP epilepsy and pregnancy registry. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(7):609-617. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70107-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morrow J, Russell A, Guthrie E, et al. Malformation risks of antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy: a prospective study from the UK Epilepsy and Pregnancy Register. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(2):193-198. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.074203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shih JJ, Whitlock JB, Chimato N, Vargas E, Karceski SC, Frank RD. Epilepsy treatment in adults and adolescents: expert opinion, 2016. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;69:186-222. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ackers R, Besag FM, Wade A, Murray ML, Wong IC. Changing trends in antiepileptic drug prescribing in girls of child-bearing potential. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94(6):443-447. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.144386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johannessen Landmark C, Larsson PG, Rytter E, Johannessen SI. Antiepileptic drugs in epilepsy and other disorders–a population-based study of prescriptions. Epilepsy Res. 2009;87(1):31-39. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2009.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Artama M, Braumann J, Raitanen J, et al. Women treated for epilepsy during pregnancy: outcomes from a nationwide population-based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2017;96(7):812-820. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thurman DJ, Beghi E, Begley CE, et al. ; ILAE Commission on Epidemiology . Standards for epidemiologic studies and surveillance of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2011;52(suppl 7):2-26. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03121.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holden EW, Thanh Nguyen H, Grossman E, et al. Estimating prevalence, incidence, and disease-related mortality for patients with epilepsy in managed care organizations. Epilepsia. 2005;46(2):311-319. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.30604.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Helmers SL, Thurman DJ, Durgin TL, Pai AK, Faught E. Descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy in the US population: A different approach. Epilepsia. 2015;56(6):942-948. doi: 10.1111/epi.13001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanner AM, Ashman E, Gloss D, et al. Practice guideline update summary: Efficacy and tolerability of the new antiepileptic drugs I: Treatment of new-onset epilepsy: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2018;91(2):74-81. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baftiu A, Landmark CJ, Rusten IR, Feet SA, Johannessen SI, Larsson PG. Erratum to: Changes in utilisation of antiepileptic drugs in epilepsy and non-epilepsy disorders—a pharmacoepidemiological study and clinical implications. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73(6):791-792. doi: 10.1007/s00228-017-2252-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baftiu A, Johannessen Landmark C, Rusten IR, Feet SA, Johannessen SI, Larsson PG. Changes in utilisation of antiepileptic drugs in epilepsy and non-epilepsy disorders-a pharmacoepidemiological study and clinical implications. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72(10):1245-1254. doi: 10.1007/s00228-016-2092-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaufman KR. Antiepileptic drugs in the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Epilepsy Behav. 2011;21(1):1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adedinsewo DA, Thurman DJ, Luo YH, Williamson RS, Odewole OA, Oakley GP Jr. Valproate prescriptions for nonepilepsy disorders in reproductive-age women. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2013;97(6):403-408. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wise J. Women still not being told about pregnancy risks of valproate. BMJ. 2017;358:j4426. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jędrzejczak J, Bomba-Opoń D, Jakiel G, Kwaśniewska A, Mirowska-Guzel D. Managing epilepsy in women of childbearing age—Polish Society of Epileptology and Polish Gynecological Society Guidelines. Ginekol Pol. 2017;88(5):278-284. doi: 10.5603/GP.a2017.0053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935-1984. Epilepsia. 1993;34(3):453-468. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1993.tb02586.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Rocca WA. Descriptive epidemiology of epilepsy: contributions of population-based studies from Rochester, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71(6):576-586. doi: 10.4065/71.6.576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnson EL, Burke AE, Wang A, Pennell PB. Unintended pregnancy, prenatal care, newborn outcomes, and breastfeeding in women with epilepsy. Neurology. 2018;91(11):e1031-e1039. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herzog AG, Mandle HB, Cahill KE, Fowler KM, Hauser WA, Davis AR. Contraceptive practices of women with epilepsy: Findings of the epilepsy birth control registry. Epilepsia. 2016;57(4):630-637. doi: 10.1111/epi.13320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Recommendations for the use of folic acid to reduce the number of cases of spina bifida and other neural tube defects. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1992;41(RR-14):1-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Use of supplements containing folic acid among women of childbearing age—United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(1):5-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Herzog AG, MacEachern DB, Mandle HB, et al. Folic acid use by women with epilepsy: Findings of the Epilepsy Birth Control Registry. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;72:156-160. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel AD, Baca C, Franklin G, et al. Quality improvement in neurology: Epilepsy Quality Measurement Set 2017 update. Neurology. 2018;91(18):829-836. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]