Key Points

Question

What is the accuracy of complete blood count parameters at routinely used thresholds in identifying young febrile infants with bacteremia or bacterial meningitis in the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era?

Findings

In this cohort of 4313 febrile infants aged 0 to 60 days, 97 (2.2%) had bacteremia or bacterial meningitis. Sensitivities were low for white blood cell counts less than 5000/µL (sensitivity, 10%; specificity, 91%), white blood cell count ≥15 000/µL (sensitivity, 27%; specificity, 87%), and absolute neutrophil count ≥10 000/µL (sensitivity, 18%; specificity, 96%).

Meaning

No complete blood cell count parameter at routinely used thresholds in isolation identified infants with bacteremia or bacterial meningitis with sufficient accuracy to substantially assist clinical decision making.

Abstract

Importance

Clinicians often risk stratify young febrile infants for invasive bacterial infections (IBIs), defined as bacteremia and/or bacterial meningitis, using complete blood cell count parameters.

Objective

To estimate the accuracy of individual complete blood cell count parameters to identify febrile infants with IBIs.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Planned secondary analysis of a prospective observational cohort study comprising 26 emergency departments in the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network from 2008 to 2013. We included febrile (≥38°C), previously healthy, full-term infants younger than 60 days for whom blood cultures were obtained. All infants had either cerebrospinal fluid cultures or 7-day follow-up.

Main Outcomes and Measures

We tested the accuracy of the white blood cell count, absolute neutrophil count, and platelet count at commonly used thresholds for IBIs. We determined optimal thresholds using receiver operating characteristic curves.

Results

Of 4313 enrolled infants, 1340 (31%; 95% CI, 30% to 32%) were aged 0 to 28 days, 2412 were boys (56%), and 2471 were white (57%). Ninety-seven (2.2%; 95% CI, 1.8% to 2.7%) had IBIs. Sensitivities were low for common complete blood cell count parameter thresholds: white blood cell count less than 5000/µL, 10% (95% CI, 4% to 16%) (to convert to 109 per liter, multiply by 0.001); white blood cell count ≥15 000/µL, 27% (95% CI, 18% to 36%); absolute neutrophil count ≥10 000/µL, 18% (95% CI, 10% to 25%) (to convert to × 109 per liter, multiply by 0.001); and platelets <100 × 103/µL, 7% (95% CI, 2% to 12%) (to convert to × 109 per liter, multiply by 1). Optimal thresholds for white blood cell count (11 600/µL), absolute neutrophil count (4100/µL), and platelet count (362 × 103/µL) were identified in models that had areas under the receiver operating characteristic curves of 0.57 (95% CI, 0.50-0.63), 0.70 (95% CI, 0.64-0.76), and 0.61 (95% CI, 0.55-0.67), respectively.

Conclusions and Relevance

No complete blood cell count parameter at commonly used or optimal thresholds identified febrile infants 60 days or younger with IBIs with high accuracy. Better diagnostic tools are needed to risk stratify young febrile infants for IBIs.

This cohort study estimates the accuracy of individual complete blood cell count parameters to identify febrile infants with invasive bacterial infections.

Introduction

Febrile infants 60 days and younger are routinely evaluated in emergency departments (ED) for serious bacterial infections including urinary tract infections (UTIs), bacteremia, and bacterial meningitis.1 Urinary tract infections are common bacterial infections2,3 and the urinalysis is a highly sensitive, noninvasive, readily available, rapid turnaround test to facilitate diagnosis.4,5 Although novel serum biomarkers are being evaluated to aid the clinician to reliably detect the presence of invasive bacterial infections (IBIs, defined by bacteremia or bacterial meningitis),6,7,8,9 the lack of reliable physical examination findings and nonspecific symptoms add to the diagnostic uncertainty for IBI.3

Several algorithms and guidelines have been used to help risk stratify young febrile infants for IBIs.10,11,12 These algorithms were developed prior to the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, although this vaccine predominantly affects older infants. In addition, screening of pregnant women for group B streptococcus and provision of intrapartum antibiotic chemoprophylaxis has led to IBI becoming less common in the well-appearing febrile young infant,13,14 making risk stratification even more challenging. While there is substantial variation in the laboratory evaluation of young febrile infants,15,16 the most commonly obtained test is the complete blood cell count (CBC). Smaller studies have demonstrated suboptimal performance characteristics of CBC parameters including the peripheral white blood cell (WBC) count and absolute neutrophil count (ANC) for IBI.17,18,19,20,21,22 However, this needs further validation in larger prospective cohorts of young febrile infants. Serum inflammatory markers, such as procalcitonin and C-reactive protein, can more accurately predict which young infants have IBIs.6,7,19 However, these newer biomarkers are still being validated and are not readily available in all EDs.23,24,25,26 Therefore, the ease and tradition of obtaining CBCs has led clinicians to continue to use CBC parameters in algorithms to help risk stratify young febrile infants.

Given the changing epidemiology of IBIs, we conducted a prospective study in which we enrolled a large, geographically diverse cohort of febrile infants and conducted a planned subanalysis to determine the performance of the CBC to identify febrile infants 60 days and younger with IBIs.

Methods

Study Design, Setting, and Population

This was a planned secondary analysis of a prospectively enrolled cohort of young febrile infants evaluated in 26 EDs in the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network between 2008 and 2013. In the parent study, we evaluated the association of host gene expression patterns with bacterial infections.26 Infants aged 60 days or younger were enrolled if they had documented temperatures of 38°C or higher and blood cultures were obtained. In addition to blood cultures, all infants had either cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) cultures obtained or telephone follow-up within 7 days of the ED visit to ascertain whether any patient had missed or developed bacterial meningitis. We excluded infants who were critically ill (eg, requiring emergent interventions such as intubation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or use of vasoactive medication), premature (completed gestational age <37 weeks), received antibiotics in the 4 days preceding the ED visit, or had major congenital malformations or comorbid medical conditions (eg, inborn errors of metabolism, congenital heart disease, chronic lung disease, immunosuppression or immunodeficiencies, or indwelling catheters or shunts). We also excluded previously enrolled infants and infants for whom the presence of bacteremia or meningitis was unknown. In addition, for this subanalysis, we excluded children whose CBC components were missing as well as febrile infants with urinary tract infections without IBIs. However, infants with urinary tract infections who also had either bacteremia and/or bacterial meningitis were included. Institutional review board approval was obtained at each site, and written consent was obtained from the guardian of each enrolled patient.

Study Definitions

We defined bacteremia and bacterial meningitis as growth of a single pathogen in blood and CSF cultures, respectively. Organisms classified a priori as contaminants included Bacillus non-cereus/non-anthracis, diphtheroids, Lactobacillus, Micrococcus, coagulase-negative staphylococci, and viridans group streptococci.

We defined leukocytosis as a WBC count 15 000 cells/µL or greater and leukopenia as a WBC count less than 5000 cells/µL (to convert to × 109 per liter, multiply by 0.001). Neutrophilia was defined as an ANC greater than 10 000 cells/µL (to convert to × 109 per liter, multiply by 0.001). These thresholds were chosen a priori because these are the thresholds used by several existing algorithms to risk stratify young febrile infants.10,11,12,27 Thrombocytosis was defined as a platelet count 450 × 103 cells/µL or greater (to convert to × 109 per liter, multiply by 1). Thrombocytopenia was evaluated at 2 different platelet count thresholds: less than 100 × 103 cells/µL and less than 150 × 103 cells/µL.28 Band counts were not routinely available and therefore were not analyzed.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures were the test characteristics of the WBC count, ANC, and platelet count to identify infants with IBIs.

Statistical Analyses

We summarized categorical variables with counts and percentages and continuous measures with medians, interquartile ranges (IQRs), means, and standard deviations. For each CBC parameter analyzed, we reported sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for the commonly used thresholds. We also analyzed likelihood ratios with 95% confidence intervals. We constructed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and determined an optimal cutoff value for each CBC parameter through minimizing the sensitivity, specificity coordinate pair from the point (1,1), also known as the Euclidean method.29,30 We calculated areas under the ROC curves (AUC), and based on prior work, we defined AUCs of less than 0.7 as having poor discriminatory value; AUCs of 0.7 to 0.8 as minimally accurate; AUCs of 0.8 to 0.9 as having good accuracy; and AUCs of greater than 0.9 as having excellent accuracy.17 We used SAS, version 9.4 software (SAS Institute) for analyses. P values less than .05 were considered significant, and all tests were 2-sided.

Results

Study Population

Of the 4795 infants included in the main study, 4313 (90.7%) met inclusion criteria for this analysis (eFigure in the Supplement). Lumbar punctures were attempted in 3384 infants (78.5%) and were successful in 3324 (98.2%). The demographic characteristics of the study population are described in Table 1. The median age was 38 days (IQR, 25-48 days).

Table 1. Demographics of the 4313 Infants in the Study Population.

| Variable Subgroup | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 2412 (56) |

| Female | 1901 (44) |

| Age, d | |

| 0-28 | 1340 (31) |

| 28-60 | 2973 (69) |

| Race | |

| White | 2473 (57) |

| Black | 1077 (25) |

| Other | 481 (11) |

| Unknown | 282 (7) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 2995 (69) |

| Hispanic | 1235 (29) |

| Unknown | 83 (2) |

| Disposition | |

| Admitted | 3171 (74) |

| Discharged | 1137 (26) |

| Othera | 5 (0) |

Includes 4 infants transferred to another facility and 1 who died (the latter infant’s blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid cultures were negative).

Invasive Bacterial Infections

Ninety-seven infants (2.2%; 95% CI, 1.8% to 2.7%) had IBIs; 73 of 4313 (1.7%; 95% CI, 1.4% to 2.1%) with isolated bacteremia and 24 (0.6%; 95% CI, 0.4% to 0.8%) with bacterial meningitis. Of the 24 infants with meningitis, 11 also had documented bacteremia. Invasive bacterial infections were identified in 57 of 1340 infants 28 days and younger (4.3%; 95% CI, 3.2% to 5.3%) and in 40 of 2973 infants aged 29 to 60 days (1.4%; 95% CI, 1.0% to 1.8%). Pathogens isolated are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Pathogens Causing Invasive Bacterial Infections in Infants Aged 0 to 60 Days.

| Pathogen | No. (%)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteremia Without Bacterial Meningitis (n = 73) |

Bacterial Meningitis Without Bacteremia (n = 13) |

Bacteremia and Bacterial Meningitis (n = 11) |

|

| Escherichia coli | 32 (43.8) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (9.1) |

| Group B streptococcus | 14 (19.2) | 3 (23.1) | 6 (54.6) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 11 (15.1) | 1 (7.7) | 0 |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 4 (5.5) | 0 | 1 (9.1) |

| Enterococcus species | 2 (2.7) | 3 (23.1) | 0 |

| Moraxella species | 2 (2.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Listeria monocytogenes | 1 (1.4) | 2 (15.4) | 0 |

| Neisseria meningitidis | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 1 (9.1) |

| Klebsiella species | 1 (1.4) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (9.1) |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 0 | 0 | 1 (9.1) |

| Other Gram-negative rodsb | 5 (6.8) | 0 | 0 |

Percentages reflect within-column percentages.

Includes 1 isolate each of Citrobacter freundii, Flavobacterium species, Pseudomonas species, Salmonella species (serogroup D), and a nonspeciated lactose-fermenting Gram-negative rod.

Accuracy of CBC Parameters in Identifying Infants With IBIs

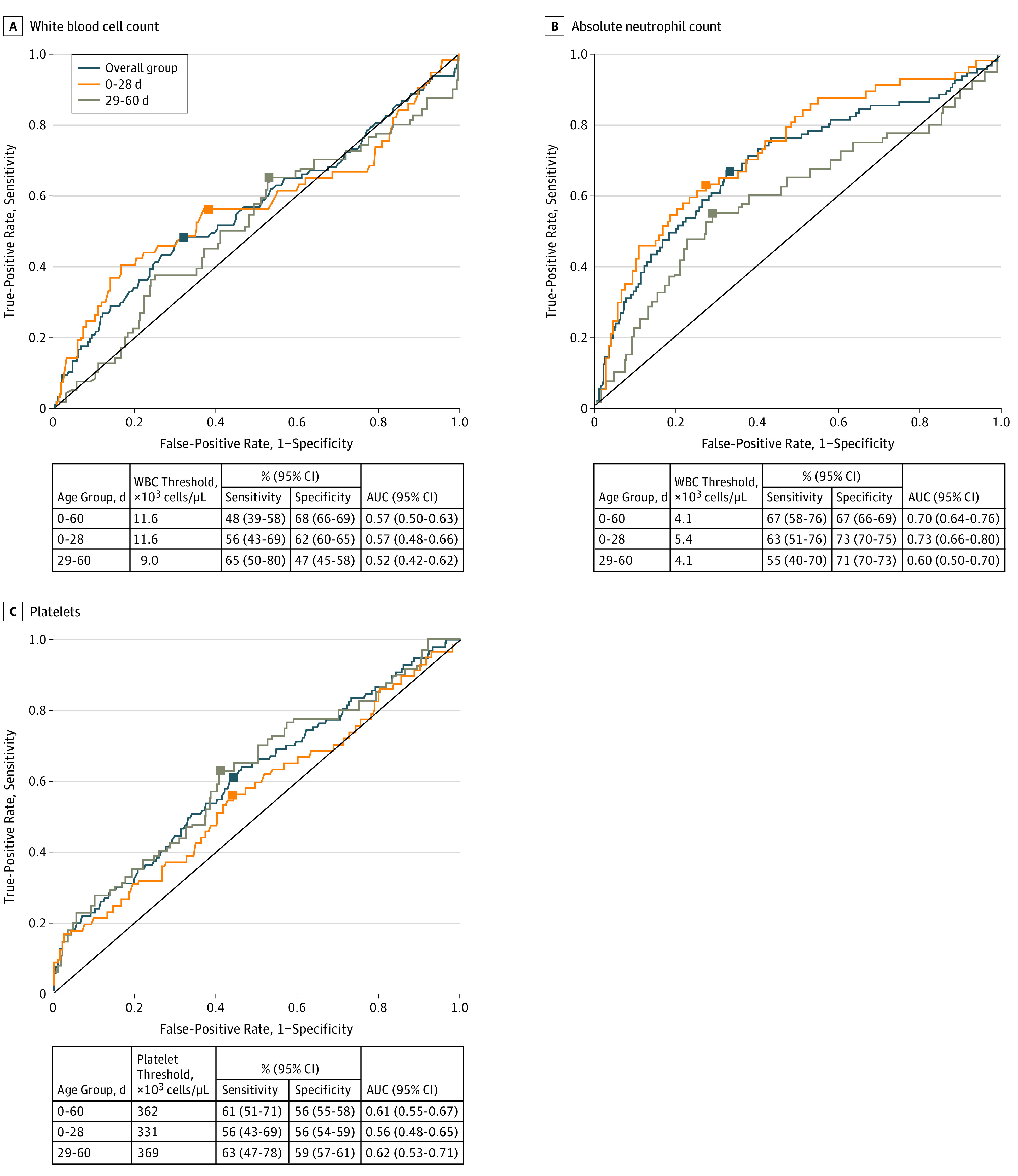

No CBC parameters reliably distinguished between infants with and without IBIs (Table 3). While children with IBIs did have higher WBC counts, ANCs, and lower platelet counts, there was not a threshold for these parameters at which IBI could be reliably predicted (Figure). The test characteristics of CBC parameters at various commonly used thresholds and optimal thresholds are presented in Table 4. Even at the optimal ANC threshold of 4100 cells/µL, one-third of infants with IBIs would have been missed. All CBC parameters had low sensitivity and high negative predictive values at commonly used thresholds. Low positive predictive values were in part owing to the low prevalence of IBIs. Using widely accepted normal ranges for WBC counts (5000 to 14 900 cells/µL) or an ANC of less than 10 × 103 cells/µL would have missed 61 (63%) and 80 (82%) of infants with IBIs, respectively.

Table 3. Comparision of Complete Blood Cell Count Parameters Between Infants With and Without Invasive Bacterial Infections.

| Parameter | Median (IQR) | P Valueb | Mean (SD) | Difference Between the Means (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants With IBI (n = 97) |

Infants Without IBI (n = 4216)a |

Infants With IBI (n = 97) | Infants Without IBI (n = 4216) |

|||

| WBC, cells/µL | 10 700 (700-15 400) | 9600 (7100-12 600) | .03 | 11 600 (5600) | 10 200 (4400) | 1.3 (0.2-2.4) |

| ANC, cells/µL | 5400 (3500-8700) | 3100 (2000-4800) | <.001 | 6200 (3900) | 3800 (2800) | 2.4 (1.6-3.2) |

| Platelet count, ×103 cells/µL | 331 (249-426) | 383 (304-467) | <.001 | 334.4 (138.4) | 393.0 (129.0) | −58.5 (−86.7 to −30.4) |

Abbreviations: ANC, absolute neutrophil count; IQR, interquartile range; WBC, white blood cell count.

SI conversion factor: To convert ANC and WBC count to × 109 per liter, multiply by 0.001; to convert platelet count to × 109 per liter, multiply by 1.

For the 4216 infants without IBI, WBCs were available for 4216 (100%), ANC for 4193 (99.5%), and platelet counts for 4189 (99.4%).

P value for Wilcoxon rank sum test.

Figure. Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves and Optimal Complete Blood Cell Count Parameter Thresholds.

Total white blood cell count (A), absolute neutrophil count (B), and platelet count (C) for identifying young febrile infants aged 0 to 28 days and 29 to 60 days with invasive bacterial infections. Black squares represent the optimal cutoffs; counts are in × 103 cells/µL. To convert absolute neutrophil count and white blood cell count to × 109 per liter, multiply by 0.001; to convert platelet count to × 109 per liter, multiply by 1.

Table 4. Test Characteristics of CBC Parameters for Identifying Infants With Invasive Bacterial Infections.

| Parameter | Threshold | % (95% CI) | LR+ (95% CI) | LR− (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Specificity | PV+ | PV− | ||||

| WBC, ×103 cells/µL | <5 | 10 (4-16) | 91 (90-92) | 3 (1-4) | 98 (97-98) | 1.1 (0.6-2.1) | 1 (0.9-1.1) |

| ≥10 | 57 (47-67) | 53 (52-55) | 3 (2-3) | 98 (98-99) | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | |

| ≥15 | 27 (18-36) | 87 (86-88) | 5 (3-6) | 98 (98-99) | 2.1 (1.5-2.9) | 0.8 (0.7-1.0) | |

| ≥20 | 9 (4-15) | 97 (97-98) | 7 (3-12) | 98 (97-98) | 3.5 (1.8-6.7) | 0.9 (0.9-1.0) | |

| <5 or ≥15 | 37 (27-47) | 78 (77-79) | 4 (3-5) | 98 (98-99) | 1.7 (1.3-2.2) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | |

| ≥11.6a | 48 (39-58) | 68 (66-69) | 3 (2-4) | 98 (98-99) | 1.5 (1.2-1.9) | 0.8 (0.6-0.9) | |

| ANC, ×103 cells/µL | ≥10 | 18 (10-25) | 96 (96-97) | 9 (5-14) | 98 (98-98) | 4.5 (2.9-7.2) | 0.9 (0.8-0.9) |

| ≥4.1a | 67 (58-76) | 67 (66-69) | 4 (3-5) | 99 (99-99) | 2.0 (1.8-2.4) | 0.5 (0.4-0.7) | |

| Platelets, ×103 cells/µL | <100 | 7 (2-12) | 100 (99-100) | 26 (9-42) | 98 (97-98) | 15.1 (6.6-34.9) | 0.9 (0.9-1) |

| <150 | 9 (4-15) | 99 (99-99) | 16 (6-25) | 98 (97-98) | 7.9 (4.0-15.7) | 0.9 (0.9-1) | |

| <150 or ≥450 | 31 (22-40) | 69 (68-71) | 2 (1-3) | 98 (97-98) | 1.0 (0.8-1.4) | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | |

| ≥450 | 22 (13-30) | 71 (69-72) | 2 (1-2) | 97 (97-98) | 0.7 (0.5-1.1) | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | |

| ≤362a | 61 (51-71) | 56 (55-58) | 3 (2-4) | 98 (98-99) | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | |

Abbreviations: ANC, absolute neutrophil count; CBC, complete blood cell count; LR, likelihood ratio; PV, predictive value; WBC, white blood cell count.

SI conversion factor: To convert absolute neutrophil to × 109 per liter, multiply by 0.001; to convert platelet count to × 109 per liter, multiply by 1; to convert white blood cell count to × 109 per liter, multiply by 0.001.

Represents optimal threshold value.

We constructed ROC curves for each individual laboratory predictor variable for infants aged 0 to 28 days and infants aged 29 to 60 days separately (Figure). Complete blood cell count test characteristics were not improved when only infants older than 28 days were considered. No single CBC parameter at any threshold had both good sensitivity and good specificity. The WBC count, ANC, and platelet count each had poor discriminatory value.

Discussion

Our analysis of a large, prospectively enrolled, geographically diverse cohort of febrile infants 60 days and younger likely represents the epidemiology of the bacterial pathogens responsible for bacteremia and bacterial meningitis. Of greater importance, our findings demonstrate that individual parameters of the CBC have poor discriminatory ability in identifying which young febrile infants have IBIs.

A minority of infants with IBIs had abnormal WBC counts. This finding is consistent with other studies evaluating young febrile infants, where peripheral leukocytosis was seen in fewer than one-half of infants with bacteremia and in a minority of infants with bacterial meningitis.31,32 We also evaluated the ability of the platelet count to identify infants with IBIs because platelets are an acute-phase reactant, and few data exist on the accuracy of platelet counts in risk stratifying young infants for IBIs.33 However, neither thrombocytosis nor thrombocytopenia, as can be seen with overwhelming infections, were sufficiently accurate. While we would expect the positive predictive value to decline and the negative predictive value to increase as the prevalence of bacteremia and bacterial meningitis decline, sensitivity and specificity of the CBC parameters should not be influenced by declining prevalence rates. One possible explanation for the CBC’s poor performance is the change of pathogens causing bacterial meningitis and bacteremia in young infants. In the pre–pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era, leukocytosis was commonly seen in older infants with Haemophilus and pneumococcal bacteremia.34,35 However, pathogens more commonly identified in the modern era may produce less of an inflammatory response by the host. A 2015 retrospective study of episodes of bacteremia in previously healthy febrile infants 90 days and younger receiving care in 17 children’s hospitals found that Escherichia coli, group B streptococcus, and Staphylococcus aureus were among the most common bacteria isolated,36 and that E coli and group B streptococcus accounted for almost two-thirds of bacterial meningitis cases in infants aged 0 to 90 days.37 E coli bacteremia is less likely to be associated with peripheral leukocytosis than pneumococcal bacteremia in infants and toddlers,38,39,40 and 1 study of infants with late-onset group B streptococcus bacteremia found that only 45% had abnormal WBC counts.40,41

Another possible explanation for why CBC parameters poorly identified infants with IBIs is that infants in our cohort may have presented earlier in the natural histories of their infections than in previous studies. In 2001, investigators42 compared parental perceptions of childhood fever with a previous study conducted in 198043 and found that in the more contemporary era, parents were more apt to check their children’s temperatures more often, worry more about seizures as a complication of pyrexia, have bloodwork performed on their children during febrile illnesses, and seek care in an ED. These concerns regarding fever may well translate into seeking care earlier in the course of an infant’s illness. One 2016 study2 found that no single CBC or inflammatory parameter or combination of parameters had optimal sensitivity for identifying infants with IBIs who had pyrexia of short durations.2 Additionally, in this study, CBCs were evaluated at one point, and the parameters may have been more accurate had CBCs been obtained later into an infant’s illness.

Complete blood cell count parameters also had suboptimal specificity for identifying infants with IBIs in our cohort. While most febrile neonates are hospitalized and administered empirical parenteral antibiotics while awaiting culture results, accurate identification of low-risk infants in the second month of life would enable reduction in resource use, costs to families, and unnecessary antibiotic exposure. However, given the low incidence of IBIs, most abnormal CBC results will not be associated with the presence of IBI. Our data add to previous literature on the poor accuracy of CBCs in identifying young febrile infants with IBIs17,18,19,20,21,22 and questions how CBC parameters, particularly the ANC, may be integrated into newer guidelines. Rather than using CBC parameters in isolation, an approach that combines certain CBC parameters (ie, the ANC) with other laboratory tests, such as the urinalysis, procalcitonin, and/or C-reactive protein (when available), may help risk stratify these febrile infants more effectively.2

Recognition that CBC parameters in isolation have poor ability to discriminate young febrile infants with and without IBIs has important implications for ED practice. Some hospital algorithms recommend only sending blood cultures in febrile infants if the WBC or ANC parameters are abnormal. The rationale is to decrease the frequency of blood culture contamination, which has historically been noted in 2% to 11% of blood cultures obtained from children in the ED.44,45,46 However, this practice would also miss most young febrile infants with IBIs. Two studies15,16 have described practice variation in terms of cultures obtained in young febrile infants, finding that even among 0- to 28-day-old neonates, fewer than two-thirds to three-quarters have blood, urine, and CSF cultures obtained.15,16 Another belief is that most infants with bacterial meningitis will have concomitant bacteremia and will thus have positive blood cultures even if CSF is not obtained at the time of the initial visit. While this was true for Haemophilus influenzae, data from the early 2000s indicate that bacteremia is only documented in 46% to 60% of infants with bacterial meningitis,47,48 consistent with our findings in this study.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. Data were collected from a convenience sample of febrile infants evaluated in the EDs of large academic children’s hospitals, and the results may thus not be generalizable to community EDs. However, the frequency of bacteremia and meningitis were similar to that described in previously published studies,31,32,39,40,48,49 and we do not have a biological hypothesis why the accuracy of the CBC would be different in different settings. Critically ill-appearing infants were not enrolled in this study, possibly leading to spectrum bias. However, most risk-stratification tools aim to identify infants at low risk for IBI, not those at high risk, and critical appearance is more important than any laboratory value for identifying those at high risk. There are some data on the utility of band counts in predicting bacteremia in this age group,50 but we were unable to assess the utility of relative or absolute bandemia for identifying those with IBIs given variation in band count availability across study EDs. Bacterial cultures were considered the reference standard for analyses, despite recognition that falsely negative cultures51 can occur owing to sporadic bacteremia or if low blood volumes are inoculated into blood culture bottles. One 2017 study found that for each additional 1 mL of blood culture volume collected, microbial yield increased by 0.5% in children with pneumonia.52

Conclusions

Complete blood cell count parameters had poor accuracy in distinguishing febrile infants 60 days and younger with and without invasive bacterial infections in the postpneumococcal conjugate vaccine era, although the ANC had the highest sensitivity. Physicians who use CBC thresholds in an attempt to risk stratify febrile young infants may be falsely reassured by normal CBC parameters. When used in isolation, either at commonly used thresholds or at the optimal thresholds identified here, CBC parameters have at best modest discriminatory ability. In an era where better screening tests exist to identify infants with IBIs, we need to question our continual reliance on a test whose greatest strength may simply be in its ready availability in clinical practice.

eFigure. Flow Diagram of Enrollment.

References

- 1.Gorelick MH, Alpern ER, Alessandrini EA. A system for grouping presenting complaints: the pediatric emergency reason for visit clusters. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(8):723-731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gomez B, Mintegi S, Bressan S, Da Dalt L, Gervaix A, Lacroix L; European Group for Validation of the Step-by-Step Approach . Validation of the “Step-by-Step” approach in the management of young febrile infants. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20154381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnadower D, Kuppermann N, Macias CG, et al. ; American Academy of Pediatrics Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee . Febrile infants with urinary tract infections at very low risk for adverse events and bacteremia. Pediatrics. 2010;126(6):1074-1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah AP, Cobb BT, Lower DR, et al. Enhanced versus automated urinalysis for screening of urinary tract infections in children in the emergency department. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(3):272-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schroeder AR, Chang PW, Shen MW, Biondi EA, Greenhow TL. Diagnostic accuracy of the urinalysis for urinary tract infection in infants <3 months of age. Pediatrics. 2015;135(6):965-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahajan P, Grzybowski M, Chen X, et al. Procalcitonin as a marker of serious bacterial infections in febrile children younger than 3 years old. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21(2):171-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milcent K, Faesch S, Gras-Le Guen C, et al. Use of procalcitonin assays to predict serious bacterial infection in young febrile infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):62-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivaska L, Niemelä J, Leino P, Mertsola J, Peltola V. Accuracy and feasibility of point-of-care white blood cell count and C-reactive protein measurements at the pediatric emergency department. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nijman RG, Moll HA, Smit FJ, et al. C-reactive protein, procalcitonin and the lab-score for detecting serious bacterial infections in febrile children at the emergency department: a prospective observational study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(11):e273-e279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dagan R, Powell KR, Hall CB, Menegus MA. Identification of infants unlikely to have serious bacterial infection although hospitalized for suspected sepsis. J Pediatr. 1985;107(6):855-860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachur RG, Harper MB. Predictive model for serious bacterial infections among infants younger than 3 months of age. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):311-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker MD, Bell LM, Avner JR. Outpatient management without antibiotics of fever in selected infants. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(20):1437-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lukacs SL, Schrag SJ. Clinical sepsis in neonates and young infants, United States, 1988-2006. J Pediatr. 2012;160(6):960-5.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrag SJ, Farley MM, Petit S, et al. Epidemiology of invasive early-onset neonatal sepsis, 2005-2014. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6):e20162013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aronson PL, Thurm C, Alpern ER, et al. ; Febrile Young Infant Research Collaborative . Variation in care of the febrile young infant <90 days in US pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):667-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain S, Cheng J, Alpern ER, et al. Management of febrile neonates in US pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2014;133(2):187-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonsu BK, Chb M, Harper MB. Identifying febrile young infants with bacteremia: is the peripheral white blood cell count an accurate screen? Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(2):216-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De S, Williams GJ, Hayen A, et al. Value of white cell count in predicting serious bacterial infection in febrile children under 5 years of age. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(6):493-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yo C-H, Hsieh P-S, Lee S-H, et al. Comparison of the test characteristics of procalcitonin to C-reactive protein and leukocytosis for the detection of serious bacterial infections in children presenting with fever without source: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(5):591-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seigel TA, Cocchi MN, Salciccioli J, et al. Inadequacy of temperature and white blood cell count in predicting bacteremia in patients with suspected infection. J Emerg Med. 2012;42(3):254-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bleeker SE, Derksen-Lubsen G, Grobbee DE, Donders ART, Moons KGM, Moll HA. Validating and updating a prediction rule for serious bacterial infection in patients with fever without source. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96(1):100-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van den Bruel A, Thompson MJ, Haj-Hassan T, et al. Diagnostic value of laboratory tests in identifying serious infections in febrile children: systematic review. BMJ. 2011;342:d3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Connelly MA, Shimizu C, Winegar DA, et al. Differences in GlycA and lipoprotein particle parameters may help distinguish acute kawasaki disease from other febrile illnesses in children. BMC Pediatr. 2016;16(1):151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim BK, Yim HE, Yoo KH. Plasma neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: a marker of acute pyelonephritis in children. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32(3):477-484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Herberg JA, Kaforou M, Wright VJ, et al. ; IRIS Consortium . Diagnostic accuracy of a 2-transcript host RNA signature for discriminating bacterial vs viral infection in febrile children. JAMA. 2016;316(8):835-845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahajan P, Kuppermann N, Mejias A, et al. ; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) . Association of RNA biosignatures with bacterial infections in febrile infants aged 60 days or younger. JAMA. 2016;316(8):846-857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonsu BK, Harper MB. A low peripheral blood white blood cell count in infants younger than 90 days increases the odds of acute bacterial meningitis relative to bacteremia. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(12):1297-1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiedmeier SE, Henry E, Sola-Visner MC, Christensen RD. Platelet reference ranges for neonates, defined using data from over 47,000 patients in a multihospital healthcare system. J Perinatol. 2009;29(2):130-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Metz CE. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Semin Nucl Med. 1978;8(4):283-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vermont J, Bosson JL, François P, Robert C, Rueff A, Demongeot J. Strategies for graphical threshold determination. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 1991;35(2):141-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenhow TL, Hung YY, Herz AM, Losada E, Pantell RH. The changing epidemiology of serious bacterial infections in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33(6):595-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenhow TL, Hung YY, Herz AM. Changing epidemiology of bacteremia in infants aged 1 week to 3 months. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):e590-e596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nosrati A, Ben Tov A, Reif S. Diagnostic markers of serious bacterial infections in febrile infants younger than 90 days old. Pediatr Int. 2014;56(1):47-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGowan JE Jr, Bratton L, Klein JO, Finland M. Bacteremia in febrile children seen in a “walk-in” pediatric clinic. N Engl J Med. 1973;288(25):1309-1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuppermann N, Fleisher GR, Jaffe DM. Predictors of occult pneumococcal bacteremia in young febrile children. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31(6):679-687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mischler M, Ryan MS, Leyenaar JK, et al. Epidemiology of bacteremia in previously healthy febrile infants: a follow-up study. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(6):293-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ouchenir L, Renaud C, Khan S, et al. The epidemiology, management, and outcomes of bacterial meningitis in infants. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1):e20170476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pereira C, Dias A, Oliveira H, Rodrigues F. Escherichia coli bacteraemia in a pediatric emergency service (1995-2010) [in Portuguese]. Acta Med Port. 2011;24(suppl 2):207-212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herz AM, Greenhow TL, Alcantara J, et al. Changing epidemiology of outpatient bacteremia in 3- to 36-month-old children after the introduction of the heptavalent-conjugated pneumococcal vaccine. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(4):293-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuppermann N. Occult bacteremia in young febrile children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999;46(6):1073-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peña BM, Harper MB, Fleisher GR. Occult bacteremia with group B streptococci in an outpatient setting. Pediatrics. 1998;102(1, pt 1):67-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crocetti M, Moghbeli N, Serwint J. Fever phobia revisited: have parental misconceptions about fever changed in 20 years? Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1241-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmitt BD. Fever phobia: misconceptions of parents about fevers. Am J Dis Child. 1980;134(2):176-181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hall KK, Lyman JA. Updated review of blood culture contamination. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(4):788-802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weddle G, Jackson MA, Selvarangan R. Reducing blood culture contamination in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2011;27(3):179-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gander RM, Byrd L, DeCrescenzo M, Hirany S, Bowen M, Baughman J. Impact of blood cultures drawn by phlebotomy on contamination rates and health care costs in a hospital emergency department. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(4):1021-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Garges HP, Moody MA, Cotten CM, et al. Neonatal meningitis: what is the correlation among cerebrospinal fluid cultures, blood cultures, and cerebrospinal fluid parameters? Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):1094-1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nigrovic LE, Kuppermann N, Malley R; Bacterial Meningitis Study Group of the Pediatric Emergency Medicine Collaborative Research Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics . Children with bacterial meningitis presenting to the emergency department during the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(6):522-528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stoll ML, Rubin LG. Incidence of occult bacteremia among highly febrile young children in the era of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine: a study from a Children’s Hospital Emergency Department and Urgent Care Center. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(7):671-675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuppermann N, Walton EA. Immature neutrophils in the blood smears of young febrile children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(3):261-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Connell TG, Rele M, Cowley D, Buttery JP, Curtis N. How reliable is a negative blood culture result? volume of blood submitted for culture in routine practice in a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2007;119(5):891-896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Driscoll AJ, Deloria Knoll M, Hammitt LL, et al. ; PERCH Study Group . The effect of antibiotic exposure and specimen volume on the detection of bacterial pathogens in children with pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl 3):S368-S377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Flow Diagram of Enrollment.