This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial investigates whether rivaroxaban is associated with a reduction in recurrent stroke among patients with embolic stroke of undetermined source who have an increased risk of atrial fibrillation.

Key Points

Question

Are patients with embolic stroke of undetermined source more likely to benefit from rivaroxaban compared with aspirin if they are at a greater risk of having atrial fibrillation?

Findings

This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial examined 7112 patients who were stratified by clinical predictors of atrial fibrillation, left atrial diameter, and frequency of premature atrial contractions. In the predefined subgroup of patients with a left atrial diameter of more than 4.6 cm, there was a significant reduction in recurrent stroke among patients who had been treated with rivaroxaban.

Meaning

Rivaroxaban appears to modestly reduce recurrent stroke in a small subgroup of patients with embolic stroke of undetermined source and moderate to severe left atrial enlargement.

Abstract

Importance

The NAVIGATE ESUS randomized clinical trial found that 15 mg of rivaroxaban per day does not reduce stroke compared with aspirin in patients with embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS); however, it substantially reduces stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF).

Objective

To analyze whether rivaroxaban is associated with a reduction of recurrent stroke among patients with ESUS who have an increased risk of AF.

Design, Setting, and Participants

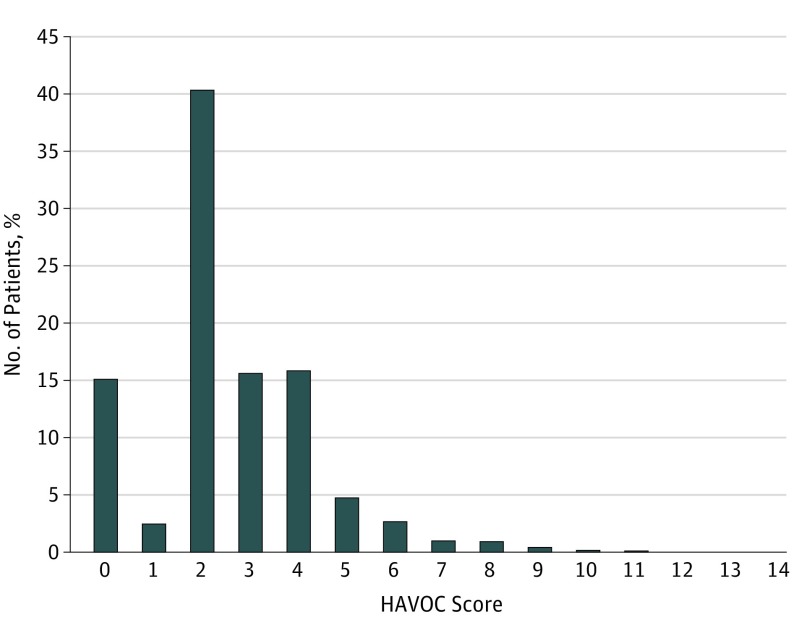

Participants were stratified by predictors of AF, including left atrial diameter, frequency of premature atrial contractions, and HAVOC score, a validated scheme using clinical features. Treatment interactions with these predictors were assessed. Participants were enrolled between December 2014 and September 2017, and analysis began March 2018.

Intervention

Rivaroxaban treatment vs aspirin.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Risk of ischemic stroke.

Results

Among 7112 patients with a mean (SD) age of 67 (9.8) years, the mean (SD) HAVOC score was 2.6 (1.8), the mean (SD) left atrial diameter was 3.8 (1.4) cm (n = 4022), and the median (interquartile range) daily frequency of premature atrial contractions was 48 (13-222). Detection of AF during follow-up increased for each tertile of HAVOC score: 2.3% (score, 0-2), 3.0% (score, 3), and 5.8% (score, >3); however, neither tertiles of the HAVOC score nor premature atrial contractions frequency impacted the association of rivaroxaban with recurrent ischemic stroke (P for interaction = .67 and .96, respectively). Atrial fibrillation annual incidence increased for each tertile of left atrial diameter (2.0%, 3.6%, and 5.2%) and for each tertile of premature atrial contractions frequency (1.3%, 2.9%, and 7.0%). Among the predefined subgroup of patients with a left atrial diameter of more than 4.6 cm (9% of overall population), the risk of ischemic stroke was lower among the rivaroxaban group (1.7% per year) compared with the aspirin group (6.5% per year) (hazard ratio, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.07-0.94; P for interaction = .02).

Conclusions and Relevance

The HAVOC score, left atrial diameter, and premature atrial contraction frequency predicted subsequent clinical AF. Rivaroxaban was associated with a reduced risk of recurrent stroke among patients with ESUS and moderate or severe left atrial enlargement; however, this needs to be independently confirmed before influencing clinical practice.

Introduction

Embolic strokes of undetermined source (ESUS) represent about 20% of all ischemic strokes and have a recurrence rate of 3% to 6% per year.1 Studies using long-term, continuous cardiac monitoring in patients with cryptogenic stroke, an older categorization that includes patients with ESUS, suggest that atrial fibrillation (AF) can be detected in approximately 30% of individuals within 3 years.2,3 Because oral anticoagulation is highly effective at preventing AF-related stroke,4,5 it is plausible that empirical anticoagulation could reduce stroke recurrence after ESUS.1 However, the New Approach Rivaroxaban Inhibition of Factor Xa in a Global Trial versus ASA to Prevent Embolism in Embolic Stroke of Undetermined Source (NAVIGATE ESUS) randomized clinical trial6 reported no reduction in stroke by 15 mg of rivaroxaban per day in patients who have had an ESUS compared with aspirin. We hypothesized that rivaroxaban may be more effective than aspirin in a subset of patients with ESUS most likely to have undiagnosed AF or markers of an abnormal left atrial substrate.

A strategy of empirical anticoagulation after a diagnosis of ESUS is attractive as it does not require time-consuming and costly cardiac monitoring. It also allows immediate initiation of therapy, which not only improves compliance, but given the period of many months required to detect most AF with cardiac monitoring, it allows delivery of therapy before stroke recurrence. Clinical characteristics,7 findings on Holter monitoring,8 and echocardiographic parameters9 all effectively identify patients at increased risk of having AF detected in the poststroke setting.7,8,9 The HAVOC score was derived using 7 common clinical patient characteristics and separated patients who previously had a stroke into 3 risk groups for future AF detection, with rates of 2.6%, 11.1%, and 20.3%.7 Although globally Holter monitoring is not consistently used after ESUS,10 an increasing burden of premature atrial contractions (PACs) can predict a 4-fold increase in the rate of subsequent AF detection8 and increased risk of ischemic stroke.11 Echocardiography is also commonly performed after ESUS, and enlarged left atrial diameter and volume have been associated with AF detection rates as high as 50% and increased stroke risk.12,13 Thus, simple, commonly available data can identify patients who have had ESUS and are at greater risk of having AF and stroke. This current secondary analysis from the NAVIGATE ESUS randomized clinical trial sought to determine if such patients were more likely to benefit from empirical treatment with rivaroxaban compared with aspirin.

Methods

The methods of the NAVIGATE ESUS trial and the baseline characteristics of its participants have been published.6 The trial enrolled 7213 patients between December 2014 and September 2017 who experienced a recent ischemic stroke and satisfied the criteria for ESUS, specifically, a nonlacunar stroke on brain imaging, open arteries (ie, <50% stenosis) proximal to the infarct, and no major-risk cardioembolic source.1 In addition to brain computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, patients required imaging of intracranial and extracranial cerebral arteries, precordial echocardiography, an electrocardiogram, and at least 24 hours of inpatient or ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring. Patients were randomly assigned, in a blinded fashion, to receive rivaroxaban (15 mg daily) or aspirin (100 mg daily). During initial investigations, 101 participants had episodes of AF or flutter of less than 6 minutes’ duration detected during cardiac monitoring and were excluded from this analysis (eFigure in Supplement 1). Median follow-up was 11 months. The trial protocol is available in Supplement 2 and was approved by supervising research ethics boards. All participating patients provided written, informed consent. Analysis began March 2018.

For this analysis, the HAVOC score was calculated using clinical patient characteristics and validated weights: 4 points for a history of congestive heart failure, 2 points for a history of coronary artery disease, 2 points for age 75 years or older, 2 points for a history of hypertension, and 2 points for documented history of cardiac valvular disease. Patients with obesity and a history of peripheral vascular disease received a single point for each. Data were also presented for the recently published AS5F score,14 which is calculated as: (age at baseline × 0.76) + 9 (+ 12 points, if baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score >5). Results of clinical precordial echocardiography and Holter monitoring were captured but not centrally reviewed, including left atrial diameter, left atrial volume (when available), and PAC frequency per 24 hours. Holter monitoring had to be at least 20 hours in duration to capture data regarding PAC frequency. Premature atrial contraction frequency was not estimated for patients who underwent inpatient cardiac monitoring or noncontinuous ambulatory monitoring, as there is no reliable methodology, to our knowledge. Although all patients underwent precordial echocardiography, left atrial measurements were frequently not available. Left atrial diameter was available for most patients and was therefore used as the primary measure of left atrial size. Although left atrial volume has superior ability to predict incident AF,15 it was not reported for a large number of patients.

At each study visit, investigators were asked to report if the patient had a new diagnosis of AF. No routine cardiac rhythm monitoring (eg, 12-lead electrocardiography or ambulatory monitoring) was mandated during follow-up.

A blinded committee of experts reviewed all potentially embolic events. The primary outcome for all analyses is ischemic stroke, which included 2% of undefined strokes without neuroimaging or autopsy. Systemic emboli were not included as there were only a small number (n = 4), and the agreement among adjudicators for these events was lower than with ischemic stroke. A sensitivity analysis examined the outcome of recurrent embolic stroke.

The HAVOC score was used as the primary method to measure AF risk in this population as it was available for virtually all patients in the NAVIGATE ESUS trial, whereas echocardiographic (left atrial diameter) and Holter data (PAC frequency) were available only for a subset. To minimize bias and owing to the small number of patients with a HAVOC score above 4, the cohort was divided by tertiles of the HAVOC score and baseline clinical, Holter monitoring, and echocardiographic characteristics compared between randomized treatment groups. The process was then repeated for patients in each tertile of left atrial diameter and PAC frequency per 24 hours. Left atrial diameter was used instead of volume because it was available for a much larger proportion of patients. An analysis examining outcomes in patients with a left atrial diameter of more than 4.6 cm was prespecified based on consensus statements and on studies showing an association between moderate or severe left atrial enlargement and stroke.16,17

Hazard ratios were calculated for each tertile of the HAVOC score, PAC frequency, and left atrial diameter to determine the association of treatment with rivaroxaban compared with aspirin. The rate of ischemic or undefined stroke was reported for each treatment arm for each tertile. The association of the HAVOC score, PAC frequency, and left atrial diameter on the association of randomized treatment was determined using an interaction P value, comparing the hazard ratios for each tertile. A 2-sided P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

This analysis included 7112 patients, with a mean (SD) HAVOC score of 2.6 (1.8) and a median (interquartile range) CHA2DS2-VASc score of 4 (3-5). Median (interquartile range) daily PAC frequency was 48 (13-222) among 2269 patients (31.9%) with at least 20 hours of continuous Holter monitoring, and the mean (SD) left atrial diameter was 3.8 (1.4) cm among 4022 patients (56.6%) with quantitative left atrial echocardiographic data. The first tertile of HAVOC score included 4130 patients (58.1%) with a score of 0 to 2; the second tertile had 1115 patients (15.7%) with a score of 3; and the third tertile had 1867 patients (26.3%) with a score of more than 3 (Table 1). Patients with a higher HAVOC score had more cardiovascular conditions, a higher CHA2DS2-VASc score, larger left atrial volume and diameter, more left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction, and greater stroke severity as measured by the modified Rankin score (Table 1). There were also significantly more PACs per 24 hours observed with increasing HAVOC tertile (Table 1).

Table 1. Baseline Clinical, Holter, and Echocardiographic Characteristics by HAVOC Score Tertile.

| Characteristic | HAVOC Score Group No. (%) | P Valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (N = 7112) | ≤2 (n = 4130) | 2 to 3 (n = 1115) | >3 (n = 1867) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 66.9 (9.8) | 63.9 (8.1) | 62.8 (7.8) | 76.0 (8.5) | <.001 |

| Male | 4378 (62) | 2762 (67) | 653 (59) | 963 (52) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 5500 (77) | 2607 (63) | 1080 (97) | 1813 (97) | <.001 |

| Heart failure | 230 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 230 (12) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 1777 (25) | 869 (21) | 393 (35) | 515 (28) | <.001 |

| Coronary disease | 459 (6) | 18 (0) | 7 (1) | 434 (23) | <.001 |

| Peripheral artery disease | 122 (2) | 13 (0) | 50 (4) | 59 (3) | <.001 |

| Pacemaker/ICD | 37 (1) | 10 (0) | 0 (0) | 27 (1) | <.001 |

| Renal disease | 227 (3) | 91 (2) | 20 (2) | 116 (6) | <.001 |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 166.9 (9.9) | 168.1 (9.5) | 167.4 (10.7) | 163.9 (9.9) | <.001 |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 76.1 (16.5) | 72.2 (13.0) | 94.8 (16.5) | 73.8 (16.0) | <.001 |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 27.2 (5.0) | 25.4 (3.4) | 33.8 (4.8) | 27.3 (4.9) | <.001 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 4.0 (3.0-4.0) | 4.0 (4.0-5.0) | 6.0 (5.0-6.0) | <.001 |

| HAVOC score, mean (SD) | 2.6 (1.8) | 1.4 (0.9) | 3.0 (0.0) | 4.8 (1.4) | <.001 |

| Proportion with middle cerebral artery stroke | 4504 (63) | 2630 (64) | 685 (61) | 1189 (64) | .36 |

| Baseline Rankin score, mean (SD) | 1.2 (1.0) | 1.1 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.0) | 1.3 (1.0) | <.001 |

| Baseline NIHSS score, mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.9) | 1.4 (1.9) | 1.5 (2.1) | 1.4 (1.8) | .82 |

| Asprin use prior to randomization | 5421 (76) | 3201 (78) | 889 (80) | 1331 (71) | <.001 |

| Statin use prior to randomization | 4364 (61) | 2529 (61) | 690 (62) | 1145 (61) | .92 |

| ACE/ARB use prior to randomization | 3135 (44) | 1450 (35) | 660 (59) | 1025 (55) | <.001 |

| LA volume, mean (SD), mL | 46.2 (24.8) | 43.5 (22.3) | 47.0 (24.7) | 51.2 (28.6) | <.001 |

| LA diameter, mean (SD), cm | 3.8 (1.4) | 3.7 (1.4) | 3.9 (1.0) | 3.9 (1.4) | <.001 |

| LVEF, mean (SD), % | 62.2 (8.1) | 63.1 (7.3) | 62.0 (7.6) | 60.3 (9.8) | <.001 |

| Global assessment of LV function | |||||

| Normal | 6322 (93) | 3790 (96) | 1004 (94) | 1528 (87) | NA |

| Mildly impaired | 384 (6) | 153 (4) | 61 (6) | 170 (10) | NA |

| Moderate-severe impaired | 89 (1) | 18 (0) | 6 (1) | 65 (4) | <.001 |

| LV hypertrophy reported | 1884 (27) | 840 (20) | 390 (35) | 654 (35) | <.001 |

| Diastolic dysfunction reported | 2148 (30) | 1124 (27) | 366 (33) | 658 (35) | <.001 |

| Total No. of atrial premature beats per 24 h, median (interquartile range)b | 48.0 (13.0-222.0) | 34.0 (10.0-136.0) | 34.5 (11.0-126.0) | 123.5 (28.0-548.0) | <.001 |

| Duration of cardiac rhythm monitoring, mean (SD), h | 81.7 (176.1) | 76.1 (152.4) | 102.6 (213.8) | 81.6 (197.9) | <.001 |

| Proportion of patients with >2 wk of monitoring | 431 (6) | 225 (5) | 97 (9) | 109 (6) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin-receptor blocker; BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); ICD, implantable cardioverter defibrillator; IQR, interquartile range; LA, left atrial; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left-ventricular ejection fraction; NA, not applicable; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; PAC, premature atrial contraction.

Continuous variables: P value from analysis of variance/Kruskal-Wallis reported; categorical variables: P value from χ2/Fisher exact test reported.

Information available only if Holter electrocardiogram performed as a measure for cardiac rhythm monitoring.

Incidence of Subsequent, Clinically Detected AF, and Use of Open-Label Anticoagulation

A total of 5245 patients (74%) had a HAVOC score of 3 or less (Figure 1). Patients with a HAVOC score of more than 3 (ie, the third tertile) had approximately twice the likelihood of future AF detection (96 [5.8%]; 95% CI, 4.9-7.0) than patients in the first (34 [2.3%]; 95% CI, 1.9-2.8) or second tertile (109 [3.0%]; 95% CI, 2.2-4.2) (P = .90). For tertiles of PAC frequency per 24 hours, the risk was 5- to 6-times higher in the third tertile (10 [7.0%]) compared with the first (22 [1.3%]) or the second (52 [2.9%]) (P = .03). For left atrial diameter, there was also a doubling in risk when comparing patients in the first tertile (24 [1.8%]) with the third (58 [4.9%]) (P = .14).

Figure 1. Distribution of HAVOC Scores Within the Study Population.

Of 239 patients diagnosed clinically with AF during the trial follow-up period post-ESUS, 228 (95%) started using open-label anticoagulation. Of these, 8 patients (4%) experienced a recurrent ischemic stroke a mean (SD) time of 58 (49) days after their reported AF. Among 11 patients (5%) who did not start using an open-label oral anticoagulant, 2 experienced a recurrent ischemic stroke a mean (SD) of 2 (1) days after their first reported AF.

Risk of Ischemic Stroke and Association of Rivaroxaban vs Aspirin by HAVOC Tertiles, Atrial Diameter, and Premature Atrial Contraction Frequency

There was no significant difference in the risk of ischemic or undetermined stroke between patients from the 3 tertiles of HAVOC score in either treatment arm (Table 2). While the hazard ratio (HR) for treatment with rivaroxaban in the top tertile was less than unity (ie, less than 1.0) (HR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.59-1.35), it was not statistically significant within this tertile, nor was the P value for interaction between randomized treatment and HAVOC tertile (Table 2). Similarly, there was no increase in stroke risk with increasing PAC frequency, nor was there any increase in the efficacy of rivaroxaban vs aspirin in the top tertile (Table 2).

Table 2. Rate of Ischemic Stroke and Association of Rivaroxaban vs Aspirin by Tertiles of HAVOC Score, Frequency of Premature Atrial Contractions, and Left Atrial Diameter.

| Subgroup | AF Reported, No. (%) | Rivaroxaban Group (n = 3563) | Aspirin Group (n = 3549) | Rivaroxaban vs Aspirin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized, No. | No. of Events (Events Ratea) | Randomized, No. | No. of Events (Events Ratea) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)b | P Value for Interactionb | P Value for Trend | ||

| Overallc | 239 (3.4) | 3563 | 158 (4.8) | 3549 | 153 (4.6) | 1.03 (0.83-1.29) | .78 | NA |

| HAVOC score | ||||||||

| 0-4 | 199 (3.1) | 3218 | 141 (4.7) | 3158 | 129 (4.4) | 1.07 (0.84-1.36) | .68 | .41 |

| 5-9 | 40 (5.6) | 332 | 16 (5.4) | 376 | 22 (6.1) | 0.86 (0.45-1.64) | ||

| 10-14 | 0 (0.0) | 13 | 1 (7.0) | 15 | 2 (17.0) | 0.23 (0.02-2.92) | ||

| HAVOC score | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-2 | 96 (2.3) | 2103 | 98 (5.1) | 2027 | 87 (4.7) | 1.08 (0.81-1.45) | .67 | .45 |

| Tertile 2: 3 | 34 (3.0) | 553 | 18 (3.4) | 562 | 15 (2.9) | 1.20 (0.61-2.39) | ||

| Tertile 3: >3 | 109 (5.8) | 907 | 42 (5.0) | 960 | 51 (5.5) | 0.89 (0.59-1.35) | ||

| Atrial premature beats per 24 hd | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-20 | 10 (1.3) | 365 | 22 (6.8) | 404 | 17 (4.5) | 1.47 (0.78-2.77) | .96 | .77 |

| Tertile 2: 21-123 | 22 (2.9) | 384 | 21 (5.8) | 368 | 14 (4.2) | 1.40 (0.71-2.76) | ||

| Tertile 3: >123 | 52 (7.0) | 347 | 22 (6.7) | 401 | 20 (5.1) | 1.31 (0.72-2.41) | ||

| Atrial premature beats per 24 hd | ||||||||

| ≤720 | 60 (3.1) | 964 | 56 (6.3) | 1003 | 40 (4.3) | 1.47 (0.98-2.20) | .53 | NA |

| >720 | 24 (7.9) | 132 | 9 (7.4) | 170 | 11 (6.7) | 1.07 (0.45-2.59) | ||

| Longest episode of SVT, mind | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-1 | 1 (1.7) | 33 | 0 (0.0) | 27 | 0 (0.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| Tertile 2: 2-5 | 2 (10.5) | 12 | 0 (0.0) | 7 | 0 (0.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| Tertile 3: >5 | 2 (5.9) | 12 | 0 (0.0) | 22 | 3 (14.4) | NA | NA | NA |

| No. of episodes of SVT per 24 hd | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-2 | 9 (2.1) | 196 | 12 (6.9) | 225 | 6 (3.0) | 2.32 (0.87-6.20) | .23 | .19 |

| Tertile 2: 3-10 | 11 (4.1) | 140 | 6 (4.3) | 131 | 7 (6.4) | 0.66 (0.22-1.98) | ||

| Tertile 3: >10 | 16 (4.9) | 162 | 8 (4.7) | 165 | 8 (5.2) | 0.96 (0.36-2.56) | ||

| LA diameter, cm | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-3.4 | 24 (1.8) | 683 | 43 (7.0) | 680 | 22 (3.5) | 1.97 (1.18-3.29) | .02 | .03 |

| Tertile 2: 3.5-4 | 50 (3.4) | 725 | 26 (3.9) | 758 | 38 (5.2) | 0.74 (0.45-1.21) | ||

| Tertile 3: >4 | 58 (4.9) | 587 | 25 (4.5) | 589 | 28 (5.0) | 0.90 (0.52-1.54) | ||

| LA diameter, cm | ||||||||

| ≤4.6 | 109 (3.0) | 1808 | 91 (5.5) | 1853 | 77 (4.4) | 1.23 (0.91-1.67) | .02 | NA |

| >4.6 | 23 (6.4) | 187 | 3 (1.7) | 174 | 11 (6.5) | 0.26 (0.07-0.94) | ||

| Combined atrial myopathy risk factorse | ||||||||

| No risk factor | 166 (2.9) | 2921 | 131 (4.9) | 2883 | 121 (4.6) | 1.07 (0.83-1.37) | .54 | NA |

| ≥1 Risk factors | 73 (5.6) | 642 | 27 (4.4) | 666 | 32 (4.9) | 0.89 (0.53-1.48) | ||

| Age, y | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-62 | 32 (1.3) | 1190 | 50 (4.7) | 1186 | 41 (3.7) | 1.24 (0.82-1.87) | .52 | .25 |

| Tertile 2: 63-71 | 78 (3.3) | 1214 | 52 (4.6) | 1178 | 48 (4.5) | 1.03 (0.70-1.53) | ||

| Tertile 3: >71 | 129 (5.5) | 1159 | 56 (5.1) | 1185 | 64 (5.7) | 0.90 (0.63-1.29) | ||

| AF5F scoref | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-56.88 | 38 (1.5) | 1256 | 52 (4.6) | 1233 | 41 (3.6) | 1.27 (0.84-1.91) | .47 | .23 |

| Tertile 2: 56.89-63.72 | 81 (3.4) | 1190 | 51 (4.6) | 1173 | 50 (4.6) | 0.99 (0.67-1.46) | ||

| Tertile 3: >63.72 | 120 (5.3) | 1117 | 55 (5.2) | 1143 | 62 (5.8) | 0.90 (0.63-1.30) | ||

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; LA, left atrial; NA, not applicable; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia.

Event rates reported in 100 person-years.

Hazard ratio, 95% CI, and P for interaction not reported if hazard ratio is ≥10 or cannot be computed.

Randomized participants in NAVIGATE ESUS without AF/flutter reported at baseline.

Information available only if Holter electrocardiogram performed as a measure for cardiac rhythm monitoring.

One point: HAVOC score, >7; 1 point: >720 premature atrial contractions per 24 hours; 1 point: LA diameter, >41 mm.

AF5F score: (age at baseline × 0.76) + 9 (+ 12 points, if baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score >5).

For the tertiles of left atrial diameter, there was a significant interaction comparing the association of rivaroxaban vs aspirin, which demonstrated a nominal reduction in ischemic stroke in the second and third tertiles, while there was an increase in ischemic stroke in the first, none of which were statistically significant within each tertile (Table 2). This significant P value for interaction is driven by a very high rate of stroke in the first tertile of rivaroxaban-treated patients (43 [7.0%]) and a low rate among aspirin-treated patients in the same tertile (22 [3.5%]).

Considering the 361 patients (9.0%) with a left atrial diameter above the normal range (ie, >4.6 cm), there was a significant benefit of rivaroxaban for the prevention of ischemic stroke compared with aspirin (HR, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.07-0.94) that was not observed in patients with smaller left atrial diameter (HR, 1.23; 95% CI, 0.91-1.67; P for interaction = .02) (Figure 2). This was driven by a much smaller rate of ischemic stroke among patients with a left atrial diameter more than 4.6 cm who were treated with rivaroxaban (1.7% per year) compared with those receiving aspirin (6.5% per year). Rivaroxaban-treated and aspirin-treated patients with a left atrial diameter of 4.6 cm or less had a higher stroke rate: 5.5% per year and 4.4% per year, respectively. Patients with a left atrial diameter more than 4.6 cm more often had AF diagnosed during follow-up (6.8% per year) than those with smaller atrial diameter (3.2% per year) (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.37-3.36; P < .001).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Curves for Time to First Ischemic Stroke .

Patients with left ventricular diameter more than 4.6 cm (A) and 4.6 cm or less (B).

In an additional exploratory analysis among 303 patients with a PAC frequency of more than 720 per 24 hours, the frequency of recurrent ischemic stroke was 7.4% per year among rivaroxaban-assigned patients and 6.7% per year among aspirin-assigned patients (HR, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.45-2.59; P = .87).

Sensitivity Analysis Using Outcome of Recurrent Embolic Stroke

The analyses of the association of HAVOC score, PAC frequency, and left atrial diameter were repeated using the outcome of embolic stroke (determined by blinded adjudication of strokes by committee) as this subgroup of ischemic strokes is believed to be most causally linked with AF. Results using this outcome (Table 3) were similar to the main results using the outcome of ischemic and undetermined stroke (Table 2).

Table 3. Sensitivity Analysis Evaluating Rivaroxaban Compared With Aspirin Using Outcome of Recurrent Embolic Stroke.

| Subgroup | AF Reported, No. (%) | Rivaroxaban Group (n = 3563) | Aspirin Group (n = 3549) | Rivaroxaban vs Aspirin | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized, No. | No. of Events (Events Ratea) | Randomized, No. | No. of Events (Events Ratea) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI)b | P Value for Interactionb | P Value for Trend | ||

| Overallc | 239 (3.4) | 3563 | 94 (2.8) | 3549 | 102 (3.1) | 0.92 (0.69-1.22) | .55 | NA |

| HAVOC score | ||||||||

| 0-4 | 199 (3.1) | 3218 | 82 (2.7) | 3158 | 87 (2.9) | 0.92 (0.68-1.25) | NA | NA |

| 5-9 | 40 (5.6) | 332 | 11 (3.6) | 376 | 15 (4.1) | 0.87 (0.40-1.89) | NA | NA |

| 10-14 | 0 (0.0) | 13 | 1 (7.0) | 15 | 0 (0.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| HAVOC score | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-2 | 96 (2.3) | 2103 | 53 (2.7) | 2027 | 54 (2.9) | 0.94 (0.64-1.37) | NA | NA |

| Tertile 2: 3 | 34 (3.0) | 553 | 14 (2.7) | 562 | 12 (2.3) | 1.17 (0.54-2.53) | NA | NA |

| Tertile 3: >3 | 109 (5.8) | 907 | 27 (3.1) | 960 | 36 (3.9) | 0.81 (0.49-1.34) | .72 | .67 |

| Atrial premature beats per 24 hd | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-20 | 10 (1.3) | 365 | 10 (3.0) | 404 | 13 (3.4) | 0.86 (0.38-1.96) | NA | NA |

| Tertile 2: 21-123 | 22 (2.9) | 384 | 10 (2.7) | 368 | 6 (1.8) | 1.59 (0.58-4.37) | NA | NA |

| Tertile 3: >123 | 52 (7.0) | 347 | 12 (3.6) | 401 | 14 (3.5) | 1.02 (0.47-2.20) | .68 | .81 |

| Atrial premature beats per 24 hd | ||||||||

| ≤720 | 60 (3.1) | 964 | 25 (2.7) | 1003 | 27 (2.9) | 0.96 (0.56-1.66) | NA | NA |

| >720 | 24 (7.9) | 132 | 7 (5.7) | 170 | 6 (3.5) | 1.56 (0.52-4.63) | .44 | NA |

| Longest episode of SVT, in minutesd | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-1 | 1 (1.7) | 33 | 0 (0.0) | 27 | 0 (0.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| Tertile 2: 2-5 | 2 (10.5) | 12 | 0 (0.0) | 7 | 0 (0.0) | NA | NA | NA |

| Tertile 3: >5 | 2 (5.9) | 12 | 0 (0.0) | 22 | 3 (14.4) | NA | NA | NA |

| No. of episodes of SVT per 24 hd | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-2 | 9 (2.1) | 196 | 5 (2.8) | 225 | 3 (1.5) | 1.93 (0.46-8.06) | NA | NA |

| Tertile 2: 3-10 | 11 (4.1) | 140 | 3 (2.1) | 131 | 6 (5.4) | 0.38 (0.09-1.52) | NA | NA |

| Tertile 3: >10 | 16 (4.9) | 162 | 6 (3.5) | 165 | 6 (3.8) | 0.95 (0.31-2.94) | .31 | .54 |

| LA diameter, cm | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-3.4 | 24 (1.8) | 683 | 21 (3.3) | 680 | 15 (2.4) | 1.39 (0.72-2.70) | NA | NA |

| Tertile 2: 3.5-4 | 50 (3.4) | 725 | 13 (1.9) | 758 | 30 (4.1) | 0.47 (0.24-0.90) | NA | NA |

| Tertile 3: >4 | 58 (4.9) | 587 | 17 (3.0) | 589 | 17 (3.0) | 1.00 (0.51-1.96) | .06 | .48 |

| LA diameter, cm | ||||||||

| ≤4.6 | 109 (3.0) | 1808 | 48 (2.8) | 1853 | 57 (3.3) | 0.87 (0.59-1.28) | NA | NA |

| >4.6 | 23 (6.4) | 187 | 3 (1.7) | 174 | 5 (2.9) | 0.58 (0.14-2.41) | .60 | NA |

| Combined atrial myopathy risk factorse | ||||||||

| No risk factor | 166 (2.9) | 2921 | 76 (2.8) | 2883 | 81 (3.0) | 0.92 (0.67-1.26) | NA | NA |

| ≥1 Risk factors | 73 (5.6) | 642 | 18 (2.9) | 666 | 21 (3.2) | 0.90 (0.48-1.69) | .96 | NA |

| Age, y | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-62 | 32 (1.3) | 1190 | 29 (2.7) | 1186 | 25 (2.3) | 1.17 (0.68-1.99) | NA | NA |

| Tertile 2: 63-71 | 78 (3.3) | 1214 | 27 (2.4) | 1178 | 35 (3.2) | 0.73 (0.44-1.21) | NA | NA |

| Tertile 3: >71 | 129 (5.5) | 1159 | 38 (3.4) | 1185 | 42 (3.7) | 0.93 (0.60-1.44) | .45 | .59 |

| AF5F scoref | ||||||||

| Tertile 1: 0-56.88 | 38 (1.5) | 1256 | 29 (2.5) | 1233 | 25 (2.2) | 1.15 (0.67-1.96) | NA | NA |

| Tertile 2: 56.89-63.72 | 81 (3.4) | 1190 | 28 (2.5) | 1173 | 36 (3.3) | 0.75 (0.46-1.23) | NA | NA |

| Tertile 3: >63.72 | 120 (5.3) | 1117 | 37 (3.5) | 1143 | 41 (3.8) | 0.92 (0.59-1.43) | .52 | 60 |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; LA, left atrial; NA, not applicable; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia.

Event rates reported in 100 person-years.

Hazard ratio, 95% CI, and P for interaction not reported if hazard ratio is ≥10 or cannot be computed.

Randomized participants in NAVIGATE ESUS without AF/Flutter reported at baseline.

Information available only if Holter electrocardiogram performed as a measure for cardiac rhythm monitoring.

One point: HAVOC score, >7; 1 point: >720 premature atrial contractions per 24 hours; 1 point: LA diameter, >41 mm.

AF5F score: (age at baseline × 0.76) + 9 (+ 12 points, if baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score >5).

Discussion

This analysis included a large number of carefully characterized individuals with a recent ESUS and found no benefit of rivaroxaban compared with aspirin among patients who had a greater likelihood of developing AF based on their HAVOC score. However, there were only about 10% of patients with ESUS in this trial who had even a moderate predicted risk of AF (ie, a HAVOC score of ≥5),7 and detection of AF during follow-up was not done systematically by required cardiac rhythm monitoring during the follow-up duration of the trial. Among the approximately 10% of individuals with at least moderate left atrial enlargement (diameter >4.6 cm),16 there was a 74% reduction in ischemic stroke among patients treated with rivaroxaban that was not seen in patients with smaller left atrial diameter and similar in magnitude to the reduction in stroke due to clinical AF seen with oral anticoagulant medications.4 Thus, using routine transthoracic echocardiography, it is possible to identify a small subset of patients with ESUS without known AF who might benefit from treatment with rivaroxaban.

Approximately 90% of patients in NAVIGATE ESUS had a HAVOC score of 4 or less, placing them at low predicted risk of AF.7 Similarly, few patients had more than 720 PACs per 24 hours or an atrial diameter above the upper reference limit.8,18 Thus, this analysis did not identify a sizeable subgroup of patients with ESUS with a very high likelihood of AF. Rather, it excluded a large group of individuals at very low risk of having AF, which should have enriched the remaining population to be more likely to benefit from empirical rivaroxaban therapy. The lack of observed benefit from rivaroxaban among patients with higher HAVOC score or PAC frequency may simply be the result of low statistical power for such a subgroup analysis. However, there was a significant interaction P value separating patients according to tertiles of atrial diameter, which was even more pronounced in the predefined subgroup of individuals with a left atrial diameter of more than 4.6 cm. Although this could simply represent the play of chance, it is likely that ability of left atrial diameter to predict an increased likelihood of benefit from rivaroxaban is the result of the reproducibility of this measurement and its strong association with stroke risk.16 It should also be noted that patients with the smallest tertile of left atrial size (≤3.4 cm) appeared to derive benefit if they were assigned to aspirin. This might suggest a benefit of antiplatelet therapy in this subgroup of patients with ESUS, perhaps due to different predominant mechanisms of stroke.19 The evolving construct of atrial myopathy postulates that a subset of embolic strokes may arise from embolism because of a dysfunctional or dilated left atrium, with or without detectable AF.20,21,22 Left atrial enlargement results from progressive remodeling due to aging, stretch from pressure and volume overload, inflammation, and oxidative stress and is associated with AF, contractile dysfunction, and an arrhythmogenic and thrombogenic substrate.20,23 We speculate that strokes occurring in individuals with significant left atrial enlargement may be more likely to arise on the basis of left atrial embolism (rather than other mechanisms) compared with individuals without left atrial enlargement and may, therefore, be more likely to be prevented by anticoagulant therapy compared with antiplatelet therapy. If our observation that anticoagulation reduces recurrent stroke in patients with atrial enlargement is confirmed in future studies, such as the ARCADIA trial (NCT03192215), left atrial enlargement may become a new treatment target for anticoagulation in secondary stroke prevention.

The lack of consistent benefit of rivaroxaban in patients at greater risk of AF may be explained by the fact that most patients in whom AF was detected received open-label oral anticoagulant before they experienced a recurrent stroke. It is possible that in the context of a clinical stroke trial, clinicians and study teams were particularly vigilant for the development of AF, treating aggressively to minimize any recurrent strokes due to previously unrecognized AF. This is particularly likely since sustained, clinically detected AF appears to convey most of the oral anticoagulant–preventable stroke risk, rather than short-lasting subclinical AF, which is more commonly identified with continuous monitoring of patients after stroke.2,3,9

Part of the anticipated benefit of using oral anticoagulant after ESUS was predicated on a 15% to 30% prevalence of unrecognized AF in this population2,3,24 and a large reduction in stroke in patients with AF.4,5 However, more than 70% of the AF detected with long-term continuous monitoring is isolated subclinical AF, which is asymptomatic, and lasting only minutes to hours intermittently over the course of many months of monitoring.2,9,25 Only 15% to 30% of patients with subclinical AF in long-term monitoring studies had AF that was clinically detected using surface electrocardiographic methods, like most of the patients this current study.2,3,25 There is growing evidence that subclinical AF is associated with a lower risk of stroke than clinically detected AF, particularly if episodes last only minutes or hours.25,26,27 In patients with subclinical AF, stroke may be due to mechanisms that may be less preventable with oral anticoagulant; such as lacunar infarction or carotid atherosclerosis.28 In patients with pacemakers and implantable defibrillators who have isolated subclinical AF, it is unclear if anticoagulation therapy should be prescribed,29 and 2 large randomized clinical trials are ongoing to determine the benefit of anticoagulation therapy for subclinical AF.30,31 If anticoagulation does not effectively prevent stroke in patients with subclinical AF, and most patients who developed clinical AF in the NAVIGATE ESUS trial received anticoagulation promptly on diagnosis, then it is not surprising that no clear benefit was seen in this analysis of patients who are at greater risk of developing AF.

Limitations

The relatively low frequency of AF detected during clinical follow-up (3% after 11.5 months) likely underestimated the true frequency if systematic assessment with long-term cardiac monitoring had been carried out. The average follow-up was only 11 months, which may have been too short for development of AF or observation of a treatment effect. Further, exploratory analyses of treatment interactions in subgroups when the overall trial results are negative must be considered as hypothesis generating and generally unsuitable for patient management.

Left atrial volume would have been a better marker of left atrial size; however, this was not reported for a large number of individuals who underwent echocardiography. Left atrial diameter was therefore used for our analyses as it was available in most cases and is generally accurately measured. Electrocardiographic measures like P terminal force were similarly not available for analysis.

Conclusions

Clinical, Holter monitor, and echocardiographic variables can identify patients with ESUS who are at greater risk of having AF; however, patients with ESUS enrolled in this trial had only a low risk of developing clinically detected AF. Neither the HAVOC score nor the frequency of PACs identified patients with ESUS more likely to benefit from rivaroxaban therapy over aspirin for reducing recurrent stroke. However, patients with left atrial enlargement, particularly the nearly 10% of patients with ESUS and a left atrial diameter greater than 4.6 cm, appear to benefit substantially from rivaroxaban therapy for secondary stroke prevention. This result from exploratory analyses on a negative overall trial must be independently reproduced before influencing clinical management.

CONSORT Diagram

Trial protocol.

References

- 1.Hart RG, Diener HC, Coutts SB, et al. ; Cryptogenic Stroke/ESUS International Working Group . Embolic strokes of undetermined source: the case for a new clinical construct. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(4):429-438. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70310-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanna T, Diener HC, Passman RS, et al. ; CRYSTAL AF Investigators . Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(26):2478-2486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gladstone DJ, Spring M, Dorian P, et al. ; EMBRACE Investigators and Coordinators . Atrial fibrillation in patients with cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(26):2467-2477. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta-analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(12):857-867. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9921):955-962. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasner SE, Lavados P, Sharma M, et al. ; NAVIGATE ESUS Steering Committee and Investigators . Characterization of patients with embolic strokes of undetermined source in the NAVIGATE ESUS randomized trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27(6):1673-1682. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.01.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwong C, Ling AY, Crawford MH, Zhao SX, Shah NH. A clinical score for predicting atrial fibrillation in patients with cryptogenic stroke or transient ischemic attack. Cardiology. 2017;138(3):133-140. doi: 10.1159/000476030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gladstone DJ, Dorian P, Spring M, et al. ; EMBRACE Steering Committee and Investigators . Atrial premature beats predict atrial fibrillation in cryptogenic stroke: results from the EMBRACE trial. Stroke. 2015;46(4):936-941. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Healey JS, Alings M, Ha A, et al. ; ASSERT-II Investigators . Subclinical atrial fibrillation in older patients. Circulation. 2017;136(14):1276-1283. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perera KS, Vanassche T, Bosch J, et al. ; ESUS Global Registry Investigators . Global survey of the frequency of atrial fibrillation-associated stroke: embolic stroke of undetermined source global registry. Stroke. 2016;47(9):2197-2202. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsen BS, Kumarathurai P, Falkenberg J, Nielsen OW, Sajadieh A. Excessive atrial ectopy and short atrial runs increase the risk of stroke beyond incident atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(3):232-241. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mounier-Vehier F, Leys D, Rondepierre P, Godefroy O, Pruvo JP. Silent infarcts in patients with ischemic stroke are related to age and size of the left atrium. Stroke. 1993;24(9):1347-1351. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.24.9.1347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Tullio MR, Sacco RL, Sciacca RR, Homma S. Left atrial size and the risk of ischemic stroke in an ethnically mixed population. Stroke. 1999;30(10):2019-2024. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.30.10.2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uphaus T, Weber-Krüger M, Grond M, et al. Development and validation of a score to detect paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after stroke. Neurology. 2019;92(2):e115-e124. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Pellikka PA, et al. 173 silent atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County: a community-based study. Can J Cardiol. 2011;27:s122. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2011.07.121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yaghi S, Moon YP, Mora-McLaughlin C, et al. Left atrial enlargement and stroke recurrence: the Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Stroke. 2015;46(6):1488-1493. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. ; American Society of Echocardiography’s Nomenclature and Standards Committee; Task Force on Chamber Quantification; American College of Cardiology Echocardiography Committee; American Heart Association; European Association of Echocardiography, European Society of Cardiology . Recommendations for chamber quantification. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2006;7(2):79-108. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2005.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binici Z, Intzilakis T, Nielsen OW, Køber L, Sajadieh A. Excessive supraventricular ectopic activity and increased risk of atrial fibrillation and stroke. Circulation. 2010;121(17):1904-1911. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.874982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rothwell PM, Algra A, Chen Z, Diener HC, Norrving B, Mehta Z. Effects of aspirin on risk and severity of early recurrent stroke after transient ischaemic attack and ischaemic stroke: time-course analysis of randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;388(10042):365-375. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30468-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kamel H, Okin PM, Elkind MS, Iadecola C. Atrial fibrillation and mechanisms of stroke: time for a new model. Stroke. 2016;47(3):895-900. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.012004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamel H, Bartz TM, Elkind MSV, et al. Atrial cardiopathy and the risk of ischemic stroke in the CHS (Cardiovascular Health Study). Stroke. 2018;49(4):980-986. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.020059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamel H, Soliman EZ, Heckbert SR, et al. P-wave morphology and the risk of incident ischemic stroke in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Stroke. 2014;45(9):2786-2788. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamel H, O’Neal WT, Okin PM, Loehr LR, Alonso A, Soliman EZ. Electrocardiographic left atrial abnormality and stroke subtype in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Ann Neurol. 2015;78(5):670-678. doi: 10.1002/ana.24482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wachter R, Gröschel K, Gelbrich G, et al. ; Find-AF(randomised) Investigators and Coordinators . Holter-electrocardiogram-monitoring in patients with acute ischaemic stroke (Find-AFRANDOMISED): an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(4):282-290. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30002-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, et al. ; ASSERT Investigators . Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):120-129. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Gelder IC, Healey JS, Crijns HJGM, et al. Duration of device-detected subclinical atrial fibrillation and occurrence of stroke in ASSERT. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(17):1339-1344. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glotzer TV, Daoud EG, Wyse DG, et al. The relationship between daily atrial tachyarrhythmia burden from implantable device diagnostics and stroke risk: the TRENDS study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(5):474-480. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.849638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perera KS, Sharma M, Connolly SJ, et al. Stroke type and severity in patients with subclinical atrial fibrillation: an analysis from the Asymptomatic Atrial Fibrillation and Stroke Evaluation in Pacemaker Patients and the Atrial Fibrillation Reduction Atrial Pacing Trial (ASSERT). Am Heart J. 2018;201:160-163. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2018.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(38):2893-2962. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirchhof P, Blank BF, Calvert M, et al. Probing oral anticoagulation in patients with atrial high rate episodes: Rationale and design of the Non-vitamin K antagonist Oral anticoagulants in patients with Atrial High rate episodes (NOAH-AFNET 6) trial. Am Heart J. 2017;190:12-18. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lopes RD, Alings M, Connolly SJ, et al. Rationale and design of the Apixaban for the Reduction of Thrombo-Embolism in Patients With Device-Detected Sub-Clinical Atrial Fibrillation (ARTESiA) trial. Am Heart J. 2017;189:137-145. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

CONSORT Diagram

Trial protocol.