Key Points

Question

What is the bleeding profile of clopidogrel plus aspirin vs aspirin alone when used to prevent strokes in patients with acute transient ischemic attack or minor ischemic stroke?

Findings

In this secondary analysis of a multinational randomized clinical trial of 4881 patients who received clopidogrel plus aspirin vs placebo plus aspirin, the risk of major hemorrhage was low and most were extracranial and treatable. Intracranial hemorrhages were rare.

Meaning

Short-term treatment with clopidogrel plus aspirin after acute transient ischemic attack or minor ischemic stroke has a low major hemorrhage complication rate and reduces the risk of ischemic stroke.

Abstract

Importance

Results show the short-term risk of hemorrhage in treating patients with acute transient ischemic attack (TIA) or minor acute ischemic stroke (AIS) with clopidogrel plus aspirin or aspirin alone.

Objective

To characterize the frequency and kinds of major hemorrhages in the Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke (POINT) trial.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This secondary analysis of the POINT randomized, double-blind clinical trial conducted in 10 countries in North America, Europe, and Australasia included patients with high-risk TIA or minor AIS who were randomized within 12 hours of symptom onset and followed up for 90 days. The total enrollment, which occurred from May 28, 2010, through December 17, 2017, was 4881 and constituted the intention-to-treat group; 4819 (98.7%) were included in the as-treated analysis group. The primary safety analyses were as-treated, classifying patients based on study drug actually received. Intention-to-treat analyses were performed as secondary analyses. Data were analyzed in April 2018.

Interventions

Patients were assigned to receive clopidogrel (600 mg loading dose on day 1 followed by 75 mg daily for days 2-90) or placebo; all patients also received open-label aspirin, 50 to 325 mg/d.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary safety outcome was all major hemorrhages. Other safety outcomes included minor hemorrhages.

Results

A total of 269 sites worldwide randomized 4881 patients (median age, 65.0 years [interquartile range, 55-74 years]; 2195 women [45.0%]); the primary results have been published previously. In the as-treated analyses, major hemorrhage occurred in 21 patients (0.9%) receiving clopidogrel plus aspirin and 6 (0.2%) in the aspirin alone group (hazard ratio, 3.57; 95% CI, 1.44-8.85; P = .003; number needed to harm, 159). There were 4 fatal hemorrhages (0.1%; 3 in the clopidogrel plus aspirin group and 1 in the aspirin alone group); 3 of the 4 were intracranial. There were 7 intracranial hemorrhages (0.1%); 5 were in the clopidogrel plus aspirin group and 2 in the aspirin plus placebo group. The most common location of major hemorrhages was in the gastrointestinal tract.

Conclusions and Relevance

The risk for major hemorrhages in patients receiving either clopidogrel plus aspirin or aspirin alone after TIA or minor AIS was low. Nevertheless, treatment with clopidogrel plus aspirin increased the risk of major hemorrhages over aspirin alone from 0.2% to 0.9%.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT00991029

This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial examines the short-term risk of hemorrhage in treating patients in North America, Europe, and Australasia with acute transient ischemic attack or minor acute ischemic stroke with clopidogrel plus aspirin or aspirin alone.

Introduction

The risk of ischemic stroke and other major vascular events shortly after a minor acute ischemic stroke (AIS) or transient ischemic attack (TIA) is high, with stroke rates ranging from 3% to 15% in the 90 days afterwards1,2 and about 4% to 6% yearly thereafter.3 Aspirin reduces the risk of recurrent ischemia by approximately 20% and is commonly initiated short-term.4,5,6,7,8 Clopidogrel inhibits platelet aggregation through the P2Y12 pathway and is frequently used, especially in patients with recurrent atherothrombotic events who are taking aspirin. Also, clopidogrel has been shown to be synergistic with aspirin in trials of patients with acute coronary syndromes. The Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients with Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events (CHANCE) trial found a 32% reduction in risk of stroke in Chinese patients treated within 24 hours of minor ischemic stroke or TIA with the combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin compared with aspirin alone.9 Consequently, some clinicians use the combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin for secondary stroke prevention, especially immediately after a minor AIS or TIA. The Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and minor ischemic stroke (POINT) trial was conducted to evaluate a regimen of clopidogrel plus aspirin in an international population of patients with minor AIS or TIA who were randomized within 12 hours of symptom onset.10 The trial was based on the expectation that these patients would be high risk for ischemic stroke, but low risk for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) because of having limited or no brain infarction. The primary results of POINT showed a 25% reduction with clopidogrel plus aspirin in the composite outcome of ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction (MI), or ischemic vascular death and a 26% reduction in stroke (ischemic and hemorrhagic).11

Major bleeding, especially intracranial hemorrhage (ICrH) and other fatal events, is the most worrisome adverse event in patients taking antithrombotic drugs. Even low doses of aspirin are associated with a risk of hemorrhagic events, including gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhages.12 Furthermore, there may be a heightened risk of ICH among patients with a history of stroke treated with potent antiplatelet therapy.13,14,15 In POINT, the clinically significant decrease in stroke with clopidogrel plus aspirin treatment was partially offset by the 3.57-fold increase (as-treated) in major hemorrhages.11 The aims of this prespecified analysis are to describe the bleeding profiles of therapy with clopidogrel plus aspirin and aspirin alone in this population of patients with TIA and AIS, characterize the major hemorrhages, and identify factors that predict major hemorrhages that may be amenable to prevention.

Methods

POINT was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial; the design and results have been published previously.10,11 Enrolled patients were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive clopidogrel plus aspirin or aspirin plus placebo. The clopidogrel plus aspirin group received a 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel, followed by 75 mg daily from day 2 to day 90. The aspirin group received a placebo load and maintenance that matched the clopidogrel tablets. Both groups also received open-label aspirin, 50 to 325 mg per day, with the dose determined by the treating physician. Each patient was followed up for a mean (SD) of 90 (14) days from randomization. Race and ethnicity were determined by self-report using fixed-category responses and included to determine representativeness of the sample. The trial was approved by institutional review boards and ethics committees according to local and national regulatory requirements and the secondary analysis was prespecified; all patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

An independent adjudication committee that was masked to treatment assignment, adjudicated all major and minor hemorrhagic events. The major hemorrhagic events are the primary focus of this analysis. The definition of major bleeding was adapted from the study protocol and the International Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis16 and Prevention Regimen for Effectively Avoiding Second Strokes trial17 definitions (eTable 1 in the Supplement). Major bleeds were those that resulted in nontraumatic, symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage, intraocular bleeding causing loss of vision, the need for transfusion of 2 or more units of red blood cells or an equivalent amount of whole blood, the need for hospitalization or a prolongation of an existing hospitalization, or death. These may include hemorrhagic events that are associated with surgical procedures. Asymptomatic hemorrhagic transformations of brain infarcts and asymptomatic cerebral microbleeds less than 10 mm evident only on gradient-echo magnetic resonance imaging were excluded from the definition of major hemorrhage, as has been the convention in recent large stroke trials.2,8,9,17,18,19,20 The definitions used by POINT better discriminate important events in the acute stroke population.

Minor bleeds were those that resulted in the interruption or discontinuation of the study drug but were not classifiable as major hemorrhagic events; these included hemorrhagic events associated with surgical procedures but not those associated with accidental trauma. Intracranial hemorrhages are all symptomatic hemorrhages inside the head. All ICrHs were categorized as major hemorrhages and are further classified as: (1) symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhages, (2) symptomatic hemorrhagic transformations of cerebral infarcts, and (3) other symptomatic intracranial hemorrhages. All ICrHs except subdural hemorrhages were considered hemorrhagic strokes.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Hemorrhages were examined in the as-treated and ITT study populations using adjudicated outcomes. The ITT population was defined under the ITT principle and included all randomized patients. The as-treated population was defined as all randomized patients who received the study drug (clopidogrel or matching placebo) and were analyzed according to the treatment taken. All patients were assigned to take aspirin but detailed compliance information was not collected. Patients who permanently discontinued using the study drug were censored the day after the permanent discontinuation. The as-treated analyses were chosen as primary for this subgroup analysis because of the high study drug discontinuation rate and because they represent the worst-case scenario for safety of the 2 treatments. The results of the ITT analyses are included for comparison and completeness (eTables 2-4 in the Supplement).

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize demographic and clinical variables. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact test (the latter when expected cell counts were <5). Medians were reported with interquartile ranges (IQRs) and were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Means were reported with standard deviations and were compared using a 2-sample t test. Because these are exploratory analyses to better understand the safety profile, a significance level of less than .05 was used for these comparisons.

A Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals for major and minor hemorrhagic outcomes. Proportions were shown for the major hemorrhage subtypes, but the HR and CIs were not shown because of the small number of events. Because event rates were low, major and minor hemorrhages were combined to explore whether clinical characteristics at baseline were associated with hemorrhages using Cox proportional hazards models with covariate baseline clinical subgroups with treatment in the models. These analyses are interpreted as highly exploratory; therefore, P values of .05 were used to assess statistical significance without adjusting for multiple comparisons.

Results

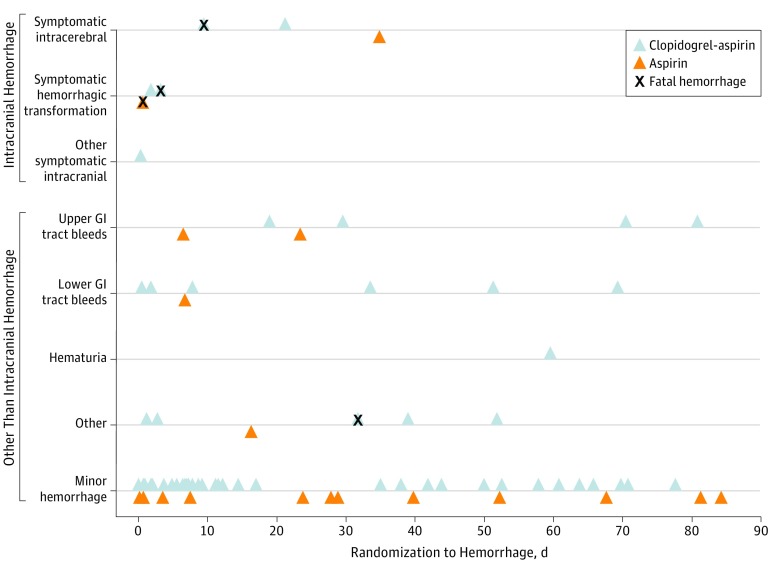

The baseline characteristics of the 4819 patients in the as-treated analysis by major hemorrhage status are shown in Table 1. A total of 33 patients (0.7%) in POINT had at least 1 major hemorrhage. Three patients (0.06%) experienced 2 major hemorrhages; 2 were in the upper GI tract and 1 was in the lower GI tract. Twenty-seven of the 33 patients with major hemorrhages (81.8%) were taking the study drug at the time of their bleed and are the subject of this as-treated analysis. The distribution of the hemorrhages over time and by location is shown in Figure 1. No patient had multiple hemorrhages while taking the study drug. Major hemorrhages occurred in 21 patients (0.9%) taking clopidogrel plus aspirin and in 6 patients (0.2%) taking aspirin alone (HR, 3.57; 95% CI, 1.44–8.85; P ≤ .003) (Table 2). In both treatment groups, the most common locations for major hemorrhages were GI tract and intracranial. eTable 5 in the Supplement shows similar results in the ITT population. Details regarding the 51 minor hemorrhages are shown in eTable 4 in the Supplement. Also, the eFigure in the Supplement shows the Kaplan-Meier curves for the risk of major and minor bleeding in the clopidogrel plus aspirin and aspirin groups. The predominant dose of aspirin was 100 mg or less, which was administered in 3578 patients (76%) in both groups.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics for the As-Treated Study Population by Major Hemorrhage Status.

| Characteristica | No. | Major Hemorrhage (n = 27) | No. | No Major Hemorrhage (n = 4792) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR), y | 27 | 74.0 (60.0-84.0) | 4792 | 65.0 (55.0-74.0) | .004 |

| Female sex, No. (%) | 27 | 15 (55.6) | 4792 | 2151 (44.9) | .27 |

| Race, No. (%) | |||||

| White | 26 | 19 (73.1) | 4655 | 3489 (75.0) | .47 |

| Black | 5 (19.2) | 953 (20.5) | |||

| Asian | 1 (3.9) | 142 (3.1) | |||

| Other | 1 (3.9) | 26 (0.6) | |||

| Ethnicity, No. (%) | |||||

| US, non-Hispanic | 26 | 24 (92.3) | 4564 | 4280 (93.8) | .68 |

| US, Hispanic | 2 (7.7) | 284 (6.2) | |||

| Region, No. (%) | |||||

| United States | 27 | 23 (85.2) | 4792 | 3965 (82.7) | >.99 |

| Outside United States | 4 (14.8) | 827 (17.3) | |||

| Blood pressure, median (IQR), mm Hg | |||||

| Systolic | 27 | 163.0 (142.0-181.0) | 4788 | 159.0 (143.0-180.0) | .56 |

| Diastolic | 27 | 85.0 (68.0-98.0) | 4788 | 87.0 (77.0-98.0) | .20 |

| Medical history, No. (%) | |||||

| Congestive heart failure | 27 | 0 (0.0) | 4785 | 122 (2.6) | >.99 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 27 | 1 (3.7) | 4778 | 47 (1.0) | .24 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 27 | 3 (11.1) | 4780 | 487 (10.2) | .75 |

| Hypertension | 26 | 22 (84.6) | 4772 | 3305 (69.3) | .13 |

| Diabetes | 27 | 8 (29.6) | 4845 | 1332 (27.5) | .80 |

| Current tobacco smoker, No. (%) | 27 | 6 (22.2) | 4789 | 987 (20.6) | .84 |

| Taking aspirin at presentation, No. (%) | 27 | 15 (55.6) | 4792 | 2761 (57.6) | .83 |

| Taking clopidogrel at presentation, No. (%) | 27 | 1 (3.7) | 4791 | 87 (1.8) | .40 |

| Prior use of PPIs, No. (%) | 27 | 10(37.0) | 4792 | 610 (12.7) | .001 |

| Time to randomization, mean (SD), h | 27 | 7.7 (3.2) | 4792 | 7.3 (2.9) | .50 |

| Time to randomization, No. (%), h | |||||

| <6 | 27 | 8 (29.6) | 4792 | 1520 (31.7) | .82 |

| >6 | 19 (70.4) | 3272 (68.3) | |||

| Qualifying event, No. (%) | |||||

| TIA | 27 | 15 (55.6) | 4792 | 2066 (43.1) | .20 |

| Ischemic stroke | 12 (44.4) | 2726 (56.9) | |||

| Qualifying TIA baseline ABCD2 score, median (IQR) | 15 | 5.0 (5.0-6.0) | 2062 | 5.0 (4.0-6.0) | .24 |

| Qualifying ischemic stroke baseline NIHSS score, median (IQR) | 12 | 2.0 (1.0-2.5) | 2703 | 2.0 (1.0-2.0) | .79 |

Abbreviations: ABCD2, age/blood pressure/clinical features/duration of symptoms/diabetes; IQR, interquartile range; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; PPI, proton pump inhibitors; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Differences in baseline characteristics between treatment groups were not significant with exception of age (P = .004) and prior use of PPIs (P = .001). Race was missing/unknown for 138 participants; ethnicity was missing/unknown for 229 participants. The ABCD2 score was given only for TIA group (n = 2081 with 4 missing). The NIHSS score was given only for ischemic stroke group (n = 2738 with 23 missing).

Figure 1. Timing of Major and Minor Hemorrhages in the As-Treated Study Population.

GI indicates gastrointestinal.

Table 2. Major and Minor Hemorrhages in the As-Treated Study Population.

| Outcome | Patients With Event, No. (%) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clopidogrel Plus Aspirin (n = 2398) | Aspirin (n = 2421) | |||

| Fatal major hemorrhagea | 3 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | NA | NA |

| Major hemorrhage | 21 (0.9) | 6 (0.2) | 3.57 (1.44-8.85) | .003 |

| Intracranial hemorrhage | 5 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | NA | NA |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 5 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | ||

| Symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | ||

| Symptomatic hemorrhagic transformation of cerebral infarcts | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.0) | ||

| Other symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (subarachnoid) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Other than intracranial hemorrhage | 16 (0.7) | 4 (0.2) | NA | NA |

| Upper GI hemorrhage | 4 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | ||

| Lower GI hemorrhage | 6 (0.3) | 1 (0.0) | ||

| Hematuria | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Otherb | 5 (0.2) | 1 (0.0) | ||

| Minor hemorrhage | 38 (1.6) | 13 (0.5) | 2.98 (1.59-5.60) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: GI, gastrointestinal; NA, not applicable.

The 4 fatal major hemorrhages consist of 1 symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, 2 symptomatic hemorrhagic transformations, and 1 groin hemorrhage with cardiac arrest.

Other consists of 1 uterine fibroid, 1 vitreous hemorrhage, 1 implant of a loop recorder, 1 gallbladder hematoma, and 1 groin hemorrhage with cardiac arrest. One patient had a traumatic arm hemorrhage due to a fall adjudicated as a major hemorrhage; according to the protocol, this should not have qualified as a major hemorrhage because it was due to accidental trauma.

The baseline characteristics of the 4819 patients in the as-treated analysis were similar across the 2 treatment groups except for age. The median age of patients with major hemorrhages was 9 years older than those without major hemorrhages. Baseline characteristics were similar when compared across treatment groups for the 27 patients with a major hemorrhage (Table 2). The 4881 randomized patients included in the ITT analyses and their baseline characteristics were similar to the primary as-treated population (eTables 2 and 6 in the Supplement).

There were 10 GI hemorrhages (0.4%) with clopidogrel plus aspirin and 3 (0.1%) with aspirin (Table 2). Of the 13 GI hemorrhages, 6 were in the upper GI tract and 7 were in the lower GI tract. The only patient with major GI bleeding that required surgery was one who was discovered to have a benign small bowel stromal tumor with active bleeding that was excised. Intracranial hemorrhages occurred in 5 patients (0.2%) receiving clopidogrel plus aspirin and in 2 patients (0.1%) receiving aspirin. All of these were hemorrhagic strokes. There were no subdural hemorrhages. There were 4 fatal hemorrhages (3 [0.1%] using clopidogrel plus aspirin and 1 [0.1%] using aspirin), 1 symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, 2 symptomatic hemorrhagic transformations, and 1 groin hemorrhage with cardiac arrest. The groin hemorrhage occurred following a mechanical thrombectomy for an AIS.

Of the 27 patients with a major hemorrhage, 21 (77.8%) stopped taking the study drug as a result of the event (16 who were taking clopidogrel plus aspirin and 5 taking aspirin alone) and 6 (22.2%) did not (5 who were taking clopidogrel plus aspirin and 1 taking aspirin alone). No patient had a second hemorrhage while taking clopidogrel or placebo. Of the 51 patients with a minor hemorrhage, 37 (72.5%) stopped taking the study drug as a result of the event (28 who were taking clopidogrel plus aspirin and 9 taking aspirin alone) and 14 (27.5%) did not (10 who were taking clopidogrel plus aspirin and 4 taking aspirin alone). The ITT analyses showed consistent findings in terms of size and direction of differences between treatment arms (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

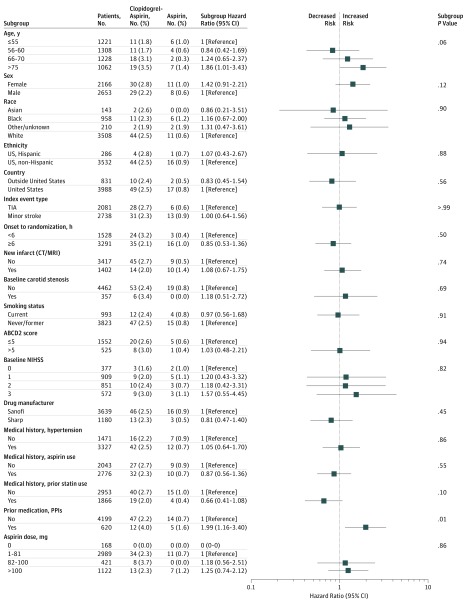

An exploratory analysis of covariate subgroups identified that using proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) within 30 days before randomization was associated with major and minor hemorrhage after adjusting for the treatment group (Figure 2; Table 3). Although the power was limited because of the small number of events and these results should be interpreted with that in mind, a Cox proportional hazards model that included treatment and prior use of PPIs indicated a difference in the rate of major and minor hemorrhages among those with prior PPI use and those without (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.16-3.40; P = .01). To further explore this finding, we fit the Cox model for major hemorrhage only and the association persisted (adjusted hazard ratio, 4.22; 95% CI, 1.93-9.21; P < .001). Overall, 10 patients (1.6%) with prior PPI use had a major hemorrhage as compared with 17 patients (0.4%) without prior PPI use (P = .001). Although the difference was not statistically significant, 6 of the 10 major hemorrhages (60.0%) that occurred in patients with prior PPI use were GI bleeds, whereas 7 of the 17 major hemorrhages (41.2%) in patients without prior use of PPIs were GI bleeds.

Figure 2. Patients With Major or Minor Hemorrhage by Subgroup in the As-Treated Study Population.

ABCD2 indicates age/blood pressure/clinical features/duration of symptoms/diabetes; CT/MRI, computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Table 3. Number of Patients With Major Hemorrhage by Subgroup in the As-Treated Study Population.

| Subgroup | Patients, No. (%) | Patients With Event, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clopidogrel Plus Aspirin | Aspirin | ||

| ABCD2 score | |||

| ≤5 | 1552 (32) | 7 (0.9) | 3 (0.4) |

| >5 | 525 (11) | 4 (1.5) | 1 (0.4) |

| Age, y | |||

| <55 | 1221 (25) | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.5) |

| 56-65 | 1308 (27) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) |

| 66-75 | 1228 (25) | 6 (1.0) | 0 (0) |

| >75 | 1062 (22) | 10 (1.8) | 3 (0.6) |

| Predominant daily aspirin dose, mga | |||

| 0 | 168 (3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0) |

| 1-81 | 2989 (62) | 15 (1.0) | 3 (0.2) |

| 82-100 | 421 (9) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) |

| >100 | 1122 (23) | 4 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) |

| Baseline carotid stenosis | |||

| No | 4462 (93) | 19 (0.9) | 6 (0.3) |

| Yes | 357 (7) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Baseline NIHSS score | |||

| 0 | 377 (8) | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| 1 | 909 (19) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) |

| 2 | 851 (18) | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) |

| 3 | 572 (12) | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0) |

| Country | |||

| Outside United States | 831 (17) | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) |

| United States | 3988 (83) | 18 (0.9) | 5 (0.2) |

| Drug manufacturer | |||

| Sanofi | 3639 (76) | 16 (0.9) | 4 (0.2) |

| Sharp | 1180 (24) | 5 (0.9) | 2 (0.3) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| US, Hispanic | 286 (6) | 2 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| US, non-Hispanic | 3532 (73) | 15 (0.9) | 5 (0.3) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2653 (45) | 10 (0.8) | 2 (0.1) |

| Female | 2166 (55) | 11 (1.0) | 4 (0.4) |

| Index event type | |||

| Minor stroke | 2738 (57) | 10 (0.7) | 2 (0.1) |

| TIA | 2081 (43) | 11 (1.1) | 4 (0.4) |

| Medical history | |||

| Hypertension | |||

| No | 1471 (31) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| Yes | 3327 (69) | 18 (1.1) | 4 (0.2) |

| Prior aspirin use | |||

| No | 2043 (42) | 9 (0.9) | 3 (0.3) |

| Yes | 2776 (58) | 12 (0.9) | 3 (0.2) |

| Prior statin use | |||

| No | 2953 (61) | 11 (0.8) | 3 (0.2) |

| Yes | 1866 (39) | 10 (1.1) | 3 (0.3) |

| New infarct (CT/MRI) | |||

| No | 3417 (71) | 14 (0.8) | 3 (0.2) |

| Yes | 1402 (29) | 7 (1.0) | 3 (0.4) |

| Onset to randomization, h | |||

| <6 | 1528 (32) | 8 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| ≥6 | 3291 (68) | 13 (0.8) | 6 (0.4) |

| Prior medication: PPIs | |||

| No | 4199 (87) | 14 (0.7) | 3 (0.1) |

| Yes | 620 (13) | 7 (2.3) | 3 (0.9) |

| Race | |||

| Asian | 143 (3) | 1 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Black | 958 (20) | 3 (0.6) | 2 (0.4) |

| Other/unknown | 210 (4) | 1 (1.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| White | 3508 (73) | 16 (0.9) | 3 (0.2) |

| Smoking status | |||

| Current | 993 (21) | 5 (1.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Never/former | 3823 (79) | 16 (0.8) | 5 (0.3) |

Abbreviations: ABCD2, age/blood pressure/clinical features/duration of symptoms/diabetes; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; TIA, transient ischemic attack; CT/MRI, computed tomography/magnetic resonance imaging; PPI, proton pump inhibitor.

Predominant daily aspirin dose missing/unknown for 119 patients.

Discussion

Patients who experience TIA or minor AIS are at substantial risk for developing a new ischemic stroke, especially in the early days and weeks after the event, even when treated with aspirin, the current standard of care. The POINT trial was designed to test the efficacy and safety of dual antiplatelet vs monoantiplatelet therapy in patients with high-risk TIA or minor AIS. More effective antiplatelet therapy could significantly reduce the overall burden of TIA/ischemic stroke if initiated soon after symptom onset, provided that such a benefit is not offset by an increase in bleeding risk. At the same time, patients with cerebral ischemic disease might be at higher risk for intracerebral hemorrhage on dual antiplatelet treatment, as suggested by results for patients with previous stroke in long-term antiplatelet studies for various indications.

In contrast, in the CHANCE trial9 that investigated patients with high-risk TIA (age/blood pressure/clinical features/duration of symptoms/diabetes ≥4) or AIS (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score ≤3), there was no increase of major bleeds during treatment with clopidogrel and aspirin (clopidogrel at an initial dose of 300 mg followed by 75 mg per day for 90 days, plus aspirin at a dose of 75 mg per day for first 21 days) vs placebo plus aspirin (75 mg per day for 90 days). Consequently, it is notable that all patients in CHANCE were receiving monotherapy (clopidogrel or aspirin) after the first 21 days, whereas in POINT half of the patients continued receiving dual therapy and the other half continued receiving monotherapy (aspirin plus placebo). Also, it is notable that clopidogrel requires conversion to an active metabolite by hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes to exert an antiplatelet effect. Polymorphisms of the CYP2C19 gene, especially certain CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles, have been identified as strong predictors of clopidogrel nonresponsiveness. In the CHANCE trial, 58.8% of the patients were carriers of loss-of-function alleles (*2, *3); using clopidogrel plus aspirin compared with aspirin alone reduced the risk of a new stroke only in the subgroup of patients who were not carriers of the loss-of-function alleles.21

The loading dose of clopidogrel in POINT was 600 mg. The purpose of a loading dose of clopidogrel is to achieve platelet P2Y12 receptor inhibition as promptly as possible and it has been shown that escalating the loading dose from 150 mg to 300 mg to 600 mg, and even 900 mg or 1200 mg, in patients with acute coronary syndrome shortens the time to maximal inhibition without increasing bleeding.22

Gastrointestinal hemorrhages accounted for the largest proportion of excess risk in the clopidogrel plus aspirin group. Upper GI tract hemorrhages are of special interest because they may be amenable to preventive gastroprotective treatment with H2-receptor antagonists. Although PPIs could also be used, there is evidence suggesting that they interfere with clopidogrel metabolism. Clopidogrel is a thienopyridine and prodrug that requires conversion to active forms with cytochrome P450 isoenzymes. Proton pump inhibitors are competitive inhibitors of the cytochrome P450 pathway. Pharmacodynamic data suggest a significant interaction between PPIs and thienopyridines23 that predisposes to major adverse cardiovascular events, including stroke. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that the coprescription of PPIs and thienopyridines increases the risk of incident ischemic strokes and the composite of stroke/myocardial infarction/cardiovascular death.24,25

Using PPIs was discouraged in POINT but not prohibited; pantoprazole was recommended as the preferred PPI for patients judged to require treatment with a PPI based on the limited data available at that time that it had less interaction with clopidogrel metabolism than other PPIs. New evidence supports this choice.26,27 During the trial, 620 patients (13%) took PPIs in the month before enrollment and as the results showed, prior PPI use was associated with a higher proportion of patients with major hemorrhage, of which most were GI bleeds. Some of these patients may have been at risk for GI hemorrhage at the time of enrollment; however, nearly half the major hemorrhagic events (4 of 10) in those with prior PPI use were not GI bleeds. Nevertheless, it is possible that discontinuing PPIs at the time of enrollment could have contributed to upper GI tract bleeds.

In a systematic review of prediction models for intracranial hemorrhage or major bleeding in patients receiving antiplatelet therapy, the investigators concluded that the predictive performance for patients with cerebral ischemia was poor.28 Consequently, we explored the covariate subgroups to identify potential predictors of major and minor hemorrhage in POINT. We found older age to be significantly associated with major hemorrhage, which agrees with the finding that older age is potently associated with major hemorrhage. In a recent publication, the S2TOP-BLEED score to predict an individualized risk of major bleeding after a TIA or ischemic stroke identified age as the strongest predictor of major bleeding.28

We observed an association between prior use of PPIs and major and minor hemorrhage. This may be due to an increased risk of GI hemorrhage in those with a prior indication for a PPI. However, the average age of patients who used a PPI was 4 years older than those who did not, so confounding by age also may have contributed to the association. While we found PPI use to be suggestive of a higher risk of major hemorrhage, the number of major bleeds was small, so our ability to identify factors associated with major or even major and minor bleeding combined to discern a specific bleeding profile was limited.

Occasionally antithrombotic treatment may uncover occult malignancies, especially GI or genitourinary, early in their progress. No malignancies were uncovered in POINT, although 1 small GI stromal tumor, benign but actively bleeding, was found in the small intestine.

The number of patients with minor bleeds was higher for clopidogrel plus aspirin (38 [1.6%]) than for aspirin alone (13 [0.5%]). Of the 51 patients with a minor bleed, 45 (88.2%) permanently stopped taking the study drug, 6 (11.8%) did not. Despite many bleeds being minor, they are important to patients and may result in reduced adherence to antiplatelet treatment. Almost all patients with a major bleed (26 of 27 [96.3%]) permanently stopped using the study drug.

Limitations

Although data for 4819 patients were included in the as-treated analysis, the number of major bleeds to assess bleed risk factors was small. This is partially explained by the limited 3-month follow-up period. However, the fact that there were few major bleeds is reassuring in a population with acute cerebral ischemia and a high risk of evolving ischemic injury.

Conclusions

The risk for major bleeding in patients receiving clopidogrel plus aspirin vs placebo plus aspirin after TIA or AIS in the POINT trial was low. Our findings suggest that for every 1000 patients treated, adding clopidogrel might prevent about 15 major ischemic events, mostly strokes, and cause 5 more major hemorrhages, mostly GI. There were only 5 fatal hemorrhages in the trial, 4 in the as-treated analysis, and 7 ICrHs. Most major hemorrhages were extracranial, treatable, and nonfatal. Nevertheless, treatment with clopidogrel plus aspirin increased the risk of major hemorrhages over placebo plus aspirin from 0.2% to 0.9%. This risk must be balanced against the observed efficacy benefit of dual antiplatelet treatment.

eTable 1. POINT, ISTH and PRoFESS Hemorrhage Classifications

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics for ITT Study Population by Major Hemorrhage Status

eTable 3. Major and Minor Hemorrhages for ITT Study Population

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Major Hemorrhages in the ITT Study Population by Treatment Group

eTable 5. Bleeding Details for Minor Hemorrhages for the As-Treated Study Population

eTable 6. Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Major Hemorrhages in the As-Treated Study Population by Treatment Group

eFigure. Kaplan Meier Curve of Major and Minor Hemorrhage in the As Treated Study Population

eAppendix. POINT Investigators

References

- 1.Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, Sidney S. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. JAMA. 2000;284(22):2901-2906. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston SC, Amarenco P, Albers GW, et al. ; SOCRATES Steering Committee and Investigators . Ticagrelor versus aspirin in acute stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(1):35-43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. ; Writing Group Members; American Heart Association Statistics Committee; Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133(4):e38-e360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease . Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2160-2236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324(7329):71-86. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CAST (Chinese Acute Stroke Trial) Collaborative Group CAST: randomised placebo-controlled trial of early aspirin use in 20,000 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Lancet. 1997;349(9066):1641-1649. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04010-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. ; American Heart Association Stroke Council . 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2018;49(3):e46-e110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Stroke Trial Collaborative Group The International Stroke Trial (IST): a randomised trial of aspirin, subcutaneous heparin, both, or neither among 19435 patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Lancet. 1997;349(9065):1569-1581. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)04011-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. ; CHANCE Investigators . Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):11-19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. Platelet-oriented inhibition in new TIA and minor ischemic stroke (POINT) trial: rationale and design. Int J Stroke. 2013;8(6):479-483. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. ; Clinical Research Collaboration, Neurological Emergencies Treatment Trials Network, and the POINT Investigators . Clopidogrel and aspirin in acute ischemic stroke and high-risk TIA. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(3):215-225. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serebruany VL, Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, et al. Analysis of risk of bleeding complications after different doses of aspirin in 192,036 patients enrolled in 31 randomized controlled trials. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95(10):1218-1222. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.01.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. ; MATCH investigators . Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9431):331-337. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16721-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiviott SD, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. ; TRITON-TIMI 38 Investigators . Prasugrel versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20):2001-2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrow DA, Braunwald E, Bonaca MP, et al. ; TRA 2P–TIMI 50 Steering Committee and Investigators . Vorapaxar in the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(15):1404-1413. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schulman S, Kearon C; Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis . Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(4):692-694. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacco RL, Diener HC, Yusuf S, et al. ; PRoFESS Study Group . Aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole versus clopidogrel for recurrent stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(12):1238-1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, et al. Management of atherothrombosis with clopidogrel in high-risk patients with recent transient ischaemic attack or ischaemic stroke (MATCH): study design and baseline data. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;17(2-3):253-261. doi: 10.1159/000076962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, Eliasziw M, Demchuk AM, Buchan AM; FASTER Investigators . Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(11):961-969. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70250-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Easton JD, Aunes M, Albers GW, et al. ; SOCRATES Steering Committee and Investigators . Risk for major bleeding in patients receiving ticagrelor compared with aspirin after transient ischemic attack or acute ischemic stroke in the SOCRATES study (Acute Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack Treated With Aspirin or Ticagrelor and Patient Outcomes). Circulation. 2017;136(10):907-916. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.028566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Zhao X, Lin J, et al. ; CHANCE investigators . Association between CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele status and efficacy of clopidogrel for risk reduction among patients with minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. JAMA. 2016;316(1):70-78. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams DO, Abbott JD. What to do with patients receiving long-term clopidogrel: reload or relax? Circulation. 2008;118(12):1219-1222. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.804229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ho PM, Maddox TM, Wang L, et al. Risk of adverse outcomes associated with concomitant use of clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors following acute coronary syndrome. JAMA. 2009;301(9):937-944. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malhotra K, Katsanos AH, Bilal M, Ishfaq MF, Goyal N, Tsivgoulis G. Cerebrovascular outcomes with proton pump inhibitors and thienopyridines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2018;49(2):312-318. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.019166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malhotra K, Katsanos AH, Tsivgoulis G. Response by Malhotra et al to the letters regarding article, “Cerebrovascular Outcomes With Proton Pump Inhibitors and Thienopyridines: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis”. Stroke. 2018;49(4):e171-e172. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drug interaction: clopidogrel and PPIs. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2017;59(1515):39-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wedemeyer RS, Blume H. Pharmacokinetic drug interaction profiles of proton pump inhibitors: an update. Drug Saf. 2014;37(4):201-211. doi: 10.1007/s40264-014-0144-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hilkens NA, Algra A, Greving JP. Prediction models for intracranial hemorrhage or major bleeding in patients on antiplatelet therapy: a systematic review and external validation study. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(1):167-174. doi: 10.1111/jth.13196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. POINT, ISTH and PRoFESS Hemorrhage Classifications

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics for ITT Study Population by Major Hemorrhage Status

eTable 3. Major and Minor Hemorrhages for ITT Study Population

eTable 4. Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Major Hemorrhages in the ITT Study Population by Treatment Group

eTable 5. Bleeding Details for Minor Hemorrhages for the As-Treated Study Population

eTable 6. Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Major Hemorrhages in the As-Treated Study Population by Treatment Group

eFigure. Kaplan Meier Curve of Major and Minor Hemorrhage in the As Treated Study Population

eAppendix. POINT Investigators