Abstract

This study uses 2011-2014 ACS NSQIP data to compare perioperative outcomes for early vs delayed cholecystectomy treatment among 1937 adult patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis.

Gallstones are the most common cause of acute pancreatitis in the United States.1,2,3,4,5 The timing of cholecystectomy among patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis (GSP) remains controversial.1,2,3,4,5,6 Many institutions delay laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) for mild GSP until normalization of laboratory values and resolution of abdominal pain, fearing early surgery may increase complications.1,3,4,5

Recent studies have shown that early LC (within 48 hours of hospital admission) results in a shorter length of stay (LOS); however, those studies were not statistically powered to detect differences in morbidity.4,5 We hypothesized that compared with delayed LC, early LC among patients with mild GSP would be associated with decreased LOS and with no difference in adverse outcomes.

Methods

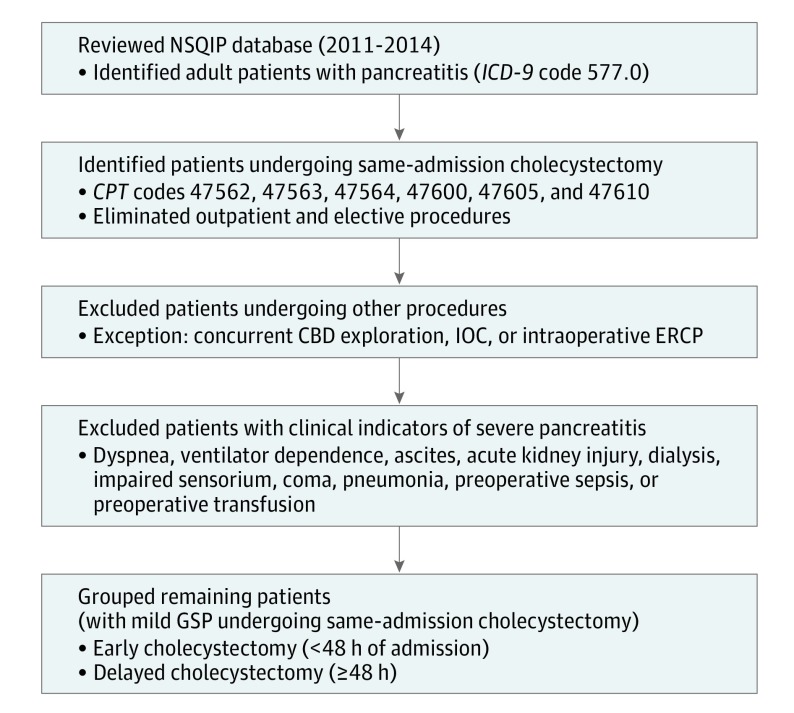

Adult patients with acute pancreatitis undergoing same-admission cholecystectomy were identified through review of the 2011 to 2014 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) database. Patients with additional nonbiliary procedures and severe pancreatitis, defined as preoperative evidence of end-organ dysfunction, were excluded. The remaining patients were then separated into early (<48 hours of hospital admission) vs delayed (≥48 hours of hospital admission) LC groups (Figure). The Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA approved this study and waived the need for informed patient consent.

Figure. Flow of Included Patients.

CBD indicates common bile duct; CPT, Current Procedural Terminology; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; GSP, gallstone pancreatitis; ICD-9, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; IOC, intraoperative cholangiography; and NSQIP, National Surgical Quality Improvement Program.

Primary outcome measures were morbidity (presence of any NSQIP-defined postoperative complication) and mortality. Secondary outcomes included LOS, operative time, reoperation, concurrent biliary interventions (including common bile duct exploration, intraoperative cholangiogram, or intraoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography), and 30-day readmissions.

The t test was used to compare continuous data, and Pearson χ2 and Fisher exact tests were used to compare categorical data. Any variable with P < .10 following bivariate analysis was included in a multivariate regression analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS, version 24.0 (IBM Corp), and 2-sided P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

We identified 1937 patients for inclusion in the study, of whom 824 (42.5%) underwent early LC. A comparison of patient demographics is given in the Table.

Table. Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics and Perioperative Outcomes.

| Characteristic or Outcome | Patients, No. (%) | OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early LC (n = 824) | Delayed LC (n = 1113) | |||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 50.1 (18.3) | 53.6 (18.8) | NA | <.001 |

| Female | 580 (70.4) | 664 (59.7) | NA | <.001 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 139 (17.6) | 194 (18.8) | NA | .51 |

| ASA class III/IV | 253 (30.7) | 513 (46.2) | NA | <.001 |

| Current smoker | 123 (14.9) | 189 (17.0) | NA | .22 |

| Diabetes | 91 (11.0) | 191 (17.2) | NA | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 287 (34.8) | 491 (44.1) | NA | <.001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2 (0.2) | 7 (0.6) | NA | .32 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 18 (2.2) | 31 (2.8) | NA | .41 |

| Steroid use for chronic condition | 12 (1.5) | 19 (1.7) | NA | .67 |

| Metastatic cancer | 3 (0.4) | 4 (0.4) | NA | .99 |

| Weight loss | 5 (0.6) | 19 (1.7) | NA | .03 |

| Bleeding disorder | 38 (4.6) | 55 (4.9) | NA | .74 |

| Preoperative open wound | 5 (0.6) | 7 (0.6) | NA | .96 |

| Preoperative total bilirubin mean (SD) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.1 (1.0) | NA | .11 |

| Perioperative Outcome | ||||

| Mortality | 2 (0.2) | 5 (0.4) | 0.54 (0.10-2.79) | .71 |

| Morbidity | 24 (2.9) | 60 (5.4) | 0.53 (0.33-0.85) | .008 |

| Laparoscopic procedure completion | 790 (95.9) | 1043 (93.7) | 1.56 (1.03-2.37) | .037 |

| Additional biliary interventions | 419 (50.8) | 422 (37.9) | 1.69 (1.41-2.03) | <.001 |

| Total LOS, mean (SD), d | 3.3 (3.7) | 7.1 (5.4) | NA | <.001 |

| Time to operation, mean (SD), d | 1.5 (0.6) | 4.6 (2.7) | NA | <.001 |

| Operative time, mean (SD), min | 70.1 (39.8) | 78 (43.2) | NA | <.001 |

| Reoperation | 6 (0.7) | 22 (2.0) | 0.37 (0.15-0.91) | .02 |

| Readmission | 38 (4.8) | 69 (6.4) | 0.74 (0.49-1.11) | .15 |

| CVA or stroke | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1.35 (0.08-21.63) | >.99 |

| Cardiac arrest | 0 | 1 (0.1) | NA | >.99 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 3 (0.3) | NA | .27 |

| Reintubation | 2 (0.2) | 6 (0.5) | 0.45 (0.09-2.23) | .48 |

| Ventilator use >48 h | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.3) | 4.50 (0.05-4.33) | .64 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 2 (0.2) | NA | .51 |

| DVT or thrombophlebitis | 0 | 3 (0.3) | NA | .27 |

| Postoperative sepsis | 6 (0.7) | 7 (0.6) | 1.16 (0.39-3.46) | .79 |

| Septic shock | 1 (0.1) | 6 (0.5) | 0.22 (0.03-1.87) | .25 |

| Acute renal failure | 0 | 3 (0.3) | NA | .27 |

| Progressive renal insufficiency | 0 | 1 (0.1) | NA | >.99 |

| Urinary tract infection | 7 (0.8) | 10 (0.9) | 0.95 (0.36-2.49) | .91 |

| Pneumonia | 6 (0.7) | 8 (0.7) | 1.01 (0.35-2.93) | .98 |

| Superficial SSI | 4 (0.5) | 9 (0.8) | 0.60 (0.18-1.95) | .39 |

| Deep incisional SSI | 0 | 2 (0.2) | NA | .51 |

| Organ space SSI | 3 (0.4) | 18 (1.6) | 0.22 (0.07-0.76) | .008 |

| Transfusion | 8 (1.0) | 27 (2.4) | 0.39 (0.18-0.87) | .02 |

Abbreviations: ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; LC, laparoscopic cholecystectomy; LOS, length of stay; NA, not applicable; OR, odds ratio; SSI, surgical site infection.

The results of bivariate analyses indicated no statistically significant difference in mortality between the early and delayed LC groups (odds ratio [OR], 0.54; 95% CI, 0.10-2.79; P = .71); however, morbidity was lower for the early group (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.33-0.85; P = .008). The early group had more laparoscopically completed procedures (OR, 1.56; 95% CI, 1.03-2.37; P = .04) and concurrent biliary interventions (OR, 1.69; 95% CI, 1.41-2.03; P < .001) in addition to a shorter mean (SD) operative time (70.1 [39.8] vs 78 [43.2] minutes; P < .001), a shorter mean (SD) total LOS (3.3 [3.7] vs 7.1 [5.4] days; P < .001), and fewer reoperations (OR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.15-0.91; P = .02). By contrast, 30-day readmissions were not different for early and delayed LC (OR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.49-1.11; P = .15) (Table).

The multivariate regression analysis results showed that early LC was independently associated with reduced LOS (β, −3.44 days; P < .001) and operative time (β, −8.48 minutes; P < .001) but was not independently associated with morbidity (OR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.40-1.13; P = .13) or reoperation (OR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.18-1.15; P = .09).

Discussion

Using the large, multicenter NSQIP database, our study found that early LC was associated with decreased LOS and operative time, with no significant increase in morbidity, mortality, or reoperation compared with delayed LC.

Prior studies have supported early LC for treatment of mild GSP based on decreased LOS, including a single-institution observational study4 (decreased LOS from 7 days to 4 days, P < .001) and a randomized prospective study5 (decreased LOS from 4 days to 3 days, P = .002).4,5,6 These prior studies were criticized, however, for being underpowered to detect differences in clinical outcomes. The LOS in our study was 4 days fewer in the early LC group than in the delayed LC group, and we observed no increased morbidity or mortality in the early LC group compared with the delayed LC group.

The limitations of the present study included the retrospective study design, with limited data available in the NSQIP database, and the inability to calculate a Ranson score. Thus, severe pancreatitis was inferred based on evidence of organ dysfunction. Despite these limitations, the results of this study add further support to the notion that early LC (<48 hours) among patients with mild GSP appears safe and therefore may be the preferred approach, with the understanding that early LC may be associated with more concurrent intraoperative biliary interventions.

References

- 1.Ranson JH. The timing of biliary surgery in acute pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1979;189(5):654-663. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197905000-00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ito K, Ito H, Whang EE. Timing of cholecystectomy for biliary pancreatitis: do the data support current guidelines? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(12):2164-2170. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0603-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor E, Wong C. The optimal timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in mild gallstone pancreatitis. Am Surg. 2004;70(11):971-975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosing DK, de Virgilio C, Yaghoubian A, et al. Early cholecystectomy for mild to moderate gallstone pancreatitis shortens hospital stay. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(6):762-766. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.06.291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aboulian A, Chan T, Yaghoubian A, et al. Early cholecystectomy safely decreases hospital stay in patients with mild gallstone pancreatitis: a randomized prospective study. Ann Surg. 2010;251(4):615-619. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c38f1f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson CT, de Moya MA. Cholecystectomy for acute gallstone pancreatitis: early vs delayed approach. Scand J Surg. 2010;99(2):81-85. doi: 10.1177/145749691009900207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]