Key Points

Question

Among veterans with kidney failure, is receipt of nephrology care in Medicare vs the Veterans Affairs health care system associated with more frequent initiation of dialysis or higher overall survival?

Findings

In this cohort study of 11 215 older veterans with kidney failure, receipt of nephrology care in Medicare was associated with a 28 percentage point higher frequency of dialysis initiation, and a 5 percentage point higher frequency of death.

Meaning

The Veterans Affairs health care system appears to favor lower intensity treatment of kidney failure without an associated increase in mortality.

Abstract

Importance

The benefits of maintenance dialysis for older adults with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are uncertain. Whether the setting of pre-ESRD nephrology care influences initiation of dialysis and mortality is not known.

Objective

To compare initiation of dialysis and mortality among older veterans with incident kidney failure who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in fee-for-service Medicare vs the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA).

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective cohort study of patients from the US Medicare and VA health care systems evaluated 11 215 veterans aged 67 years or older with incident kidney failure between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2011. Data analysis was performed March 15, 2016, through September 20, 2017.

Exposures

Pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare vs VA health care systems.

Main Outcome and Measures

Dialysis treatment and death within 2 years.

Results

Of the 11 215 patients included in the study, 11 085 (98.8%) were men; mean (SD) age was 79.1 (6.9) years. Within 2 years of incident kidney failure, 7071 (63.0%) of the patients started dialysis and 5280 (47.1%) died. Patients who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare were more likely to undergo dialysis compared with patients who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in VA (82% vs 53%; adjusted risk difference, 28 percentage points; 95% CI, 26-30 percentage points). Differences in dialysis initiation between Medicare and VA were more pronounced among patients aged 80 years or older and patients with dementia or metastatic cancer, and less pronounced among patients with paralysis (P < .05 for interaction). Two-year mortality was higher for patients who received pre-ESRD care in Medicare compared with VA (53% vs 44%; adjusted risk difference, 5 percentage points; 95% CI, 3-7 percentage points). The findings were similar in a propensity-matched analysis.

Conclusions and Relevance

Veterans who receive pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare receive dialysis more often yet are also more likely to die within 2 years compared with those in VA. The VA’s integrated health care system and financing appear to favor lower-intensity treatment for kidney failure in older patients without a concomitant increase in mortality.

This cohort study compares use of dialysis and survival in patients with end-stage renal disease who receive care through Veterans Affairs vs Medicare.

Introduction

The benefits of maintenance dialysis for older adults who develop kidney failure or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the context of another serious illness or multimorbidity are uncertain.1 In such patients, survival with dialysis may be limited, functional outcomes are often poor, and dialysis discontinuation is common.2,3 Guidelines encourage a shared decision-making process that considers patient preferences, prognosis, and expected quality of life with dialysis, but they lack consensus about which patients should forgo dialysis.1,4 Similar to other high-cost intensive procedures, the likelihood of receiving dialysis treatment varies across geographic regions among older Americans, suggesting that factors external to the patient influence dialysis decisions.5 Dialysis treatment appears to be more frequent in the United States compared with other industrialized countries, but dialysis outcomes are generally worse in the United States.6 Still, the appropriate rate of dialysis initiation is unknown, as there are differences in demographic characteristics and cultural values that confound international comparisons.

The presence of multiple delivery systems in the United States for veterans affords the opportunity of a natural experiment. Veterans older than 65 years account for almost 20% of patients starting maintenance dialysis in the United States, with an annual cost of care exceeding $100 000 per patient.7,8 Nearly all older veterans eligible for care in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system are also eligible for Medicare.9 Older veterans can therefore receive pre-ESRD nephrology care in VA or Medicare; these encounters in turn shape decisions about whether to start dialysis. Compared with the Medicare fee-for-service system, the VA has an integrated health care system with no direct financial incentives to initiate dialysis in patients for whom the benefits are expected to be limited.

Prior studies comparing outcomes of veterans who received care in VA vs non-VA settings have been limited to patients who started dialysis.9,10,11 Whether receipt of pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare vs VA is associated with more frequent use of dialysis and/or higher overall survival is unknown. To provide a more complete picture of the role of setting of care on ESRD treatment and outcomes, in the present study we compared initiation of dialysis and mortality among older veterans with incident kidney failure who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare vs VA.

Methods

Cohort

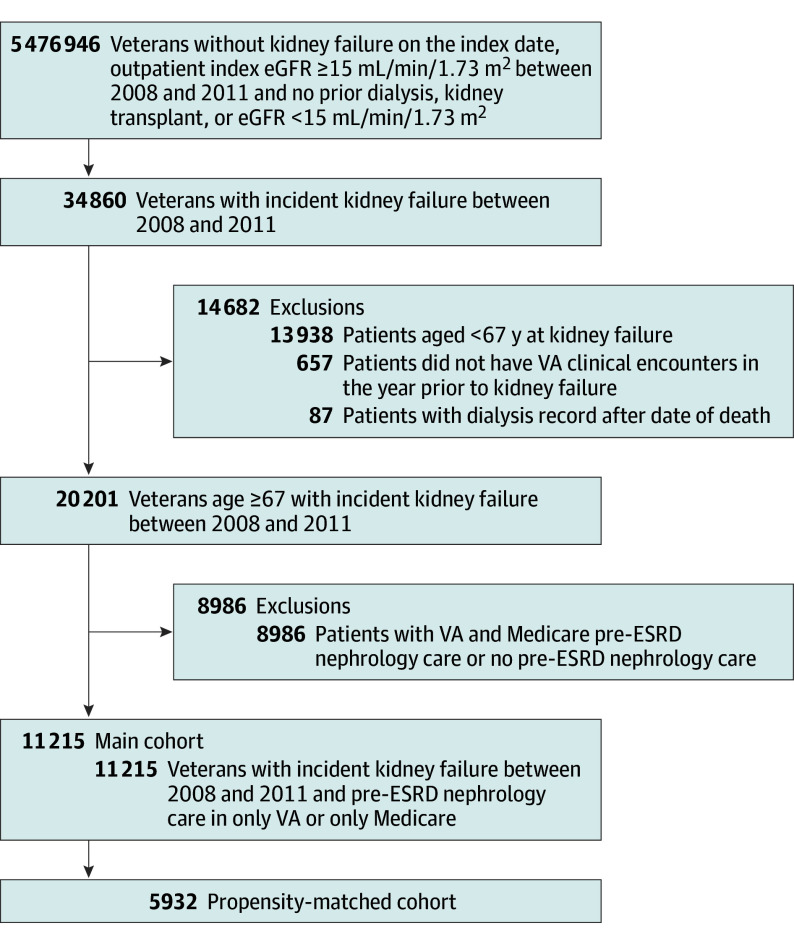

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of US veterans using laboratory and administrative data from the VA, Medicare claims, and the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), a national registry of patients receiving dialysis therapy for ESRD. We used laboratory data from the VA Decision Support System Laboratory Results file to identify all veterans with an outpatient measurement of serum creatinine between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2011. We used the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) from serum creatinine measurements and demographic characteristics.12 Of the 5 476 946 veterans who did not have kidney failure on the index (first) eGFR date (Figure 1), we identified 34 860 individuals who developed incident kidney failure between the index eGFR date and December 31, 2011. Because the term ESRD is sometimes used synonymously with dialysis treatment, we used the term incident kidney failure in the present study, defined as progression to a sustained eGFR less than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 during the follow-up period or initiation of maintenance dialysis, whichever came first, consistent with prior studies on dialysis initiation and the chronic kidney disease classification system.13 To satisfy the former criteria, we required that patients have (1) at least 2 eGFR measures less than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 at least 5 days apart, including 1 outpatient measurement, or (2) 1 outpatient eGFR less than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 and 1 VA or Medicare claim for ESRD within a 12-month period (claim + laboratory ascertainment method). We included the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) claims-based criteria for ESRD (ICD-9 codes 585.5, 585.6, 586.0, 403.01, and 403.91) to capture patients with incident kidney failure who received some care outside of the VA health care system because laboratory measurements outside of the VA were not available in the data set. In a separate validation study (eMethods and eTable 1 in the Supplement), the claims + laboratory ascertainment method had a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 99% for identifying patients with a sustained eGFR less than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 who were not receiving dialysis.

Figure 1. Cohort Flowchart.

Derivation of analytic cohort of veterans with incident kidney failure. eGFR indicates estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; and VA, Veterans Affairs.

We excluded patients younger than 67 years so that we could ascertain pre-ESRD nephrology care in VA and Medicare for 2 years prior to kidney failure, patients with a dialysis record after the date of death, and patients who did not have any VA clinical encounters in the year prior to incident kidney failure. Our primary interest was comparing those exclusively using Medicare or VA for nephrology care; therefore, we excluded 8986 patients who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in both VA and Medicare or in neither health care system, resulting in an analytic cohort of 11 215 patients (Figure 1). The institutional review board at Stanford University and the research and development committee of Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System approved the study with waiver of informed consent.

Exposures

The primary exposure for this study was the setting of pre-ESRD nephrology care over 2 years prior to kidney failure incidence: Medicare or VA. We ascertained outpatient nephrology care using clinic stop codes and clinician codes in VA administrative files and with physician specialty codes in Medicare files.

Outcome

The primary outcomes for this study were treatment with maintenance dialysis and mortality within 2 years of incident kidney failure. We identified patients who received maintenance dialysis through the USRDS or by the presence of at least 2 ICD-9 codes (3995, 5498, V56, V56.8, and V45.1) or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) dialysis codes (90935, 90937, 90945, and 90947). To exclude dialysis that is performed for acute kidney injury, we required that patients have at least 1 outpatient dialysis code, with at least 30 days between the first and last code, consistent with prior studies.14 Patients were followed up from the incident date of kidney failure through December 31, 2013, to ascertain the primary outcomes so that all patients had at least 2 years of follow-up.

Covariates

We used VA administrative data, Medicare files, and the USRDS to record age, sex, race, marital status, and VA co-pay. We used patient zip code to estimate driving distance to the closest VA medical center with nephrology subspecialty care and median income from census data. We ascertained comorbid conditions from the VA medical SAS-format data sets and Medicare claims using ICD-9 and CPT codes and calculated the Charlson Comorbidity Index value using the Deyo modification.15 We calculated the rate of eGFR decline prior to incident kidney failure based on the change in eGFR from the index date to the date of kidney failure and categorized this as less than 5, 5 to 10, and more than 10 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year. For patients whose qualifying kidney failure event was dialysis initiation, we used the eGFR recorded on the USRDS Medical Evidence Form to determine the change in eGFR from the index date to kidney failure, and when this was missing, the closest VA eGFR within 90 days prior to dialysis initiation.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as percentages. We used modified Poisson regression to determine the association, expressed as a relative risk, along with 95% CIs, between the site of pre-ESRD nephrology care and each outcome: dialysis treatment and death within 2 years of kidney failure incidence.16,17 We computed risk differences through marginal standardization using the margins command in Stata, version 13.1 (StataCorp).18

We constructed models to determine the association between site of care and each outcome adjusting for patient sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, race, marital status, zip code, median income, and urban residence), clinical characteristics (comorbid conditions and rate of eGFR decline), access to VA health care (driving distance to VA, VA co-pay) and calendar year. Of 11 215 patients, 1142 (10.2%) were missing 1 or more covariates. To address missing covariates, we used multiple imputation techniques based on the joint modeling approach used in SAS’s PROC MI and summarized findings across models for each imputed data set using Rubin’s rules. We evaluated whether the association between site of care and dialysis treatment was modified by age (<80 or ≥80 years), race, Charlson Comorbidity Index score (<4 and ≥4), and selected serious comorbid conditions (dementia, metastatic cancer, and paralysis), using stratified models and interaction terms. We also performed sensitivity analyses restricted to patients with 2 or more pre-ESRD nephrology visits and, separately, patients who progressed to a sustained eGFR less than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2. In addition, we applied a more stringent criterion for the eGFR component of incident kidney failure, requiring 2 eGFR measurements less than 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 at least 90 days apart.

Propensity-Matched Analyses

Because patients who use Medicare for subspecialty care differ from those who use the VA in several important characteristics that could confound the association between setting of care and outcome, we also conducted a propensity score–matched analysis. To estimate propensity scores, we used logistic regression to model the likelihood of receiving pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare vs VA using the patient characteristics listed in Table 1. We matched patients who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare to patients who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in VA in a 1:1 ratio, using a caliper distance of less than 0.2.19 We matched 87% of patients with nonmissing data who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare to VA patients, resulting in an analytic cohort of 5932 patients. We assessed match quality with standardized differences. Because the propensity-matched groups were well balanced on measured characteristics (standardized differences <10%), the analyses were not further adjusted.

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients Receiving Pre-ESRD Nephrology Care in VA vs Medicare, Before and After Propensity-Score Matching.

| Patient Characteristics | Before Matching | After Matching | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicare (n = 3974) | VA (n = 7241) | Standardized Difference | Medicare (n = 2966) | VA (n = 2966) | Standardized Difference | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 80 (6) | 78 (5) | 24.2 | 80 (6) | 80 (7) | 2.2 |

| Male, No. (%) | 3943 (99.2) | 7142 (98.6) | 5.7 | 2941 (99.2) | 2935 (99.0) | 2.2 |

| Race, No. (%) | ||||||

| White | 3402 (85.6) | 4872 (67.3) | 47.2 | 2490 (84.0) | 2490 (84.0) | 2.6 |

| Black | 295 (7.4) | 1653 (22.8) | 259 (8.7) | 259 (8.7) | ||

| Other | 245 (6.2) | 646 (8.9) | 188 (6.3) | 188 (6.3) | ||

| Missing | 32 (0.8) | 70 (1.0) | 29 (1.0) | 29 (1.0) | ||

| Married, No. (%) | 2996 (75.4) | 4025 (55.6) | 42.6 | 2166 (73.0) | 2144 (72.3) | 1.7 |

| Driving distance to closest VA, mean (SD), miles | 63 (50) | 38 (39) | 55.9 | 56 (44) | 53 (47) | 7.2 |

| Missing, No. (%) | 8 (0.2) | 10 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Copayment for VA services, No. (%) | 3429 (86.3) | 5878 (81.2) | 15.2 | 2532 (85.4) | 2518 (84.9) | 2.4 |

| Urban residence, No. (%) | 3117 (78.4) | 6016 (83.1) | −11.8 | 2414 (81.4) | 2400 (80.9) | 1.2 |

| Zip code median income, mean (SD) ($, in thousands) | 52 (19) | 49 (18) | 17.7 | 52 (18) | 52 (19) | −0.1 |

| Missing, No. (%) | 48 (1.2) | 147 (2.0) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Comorbidity, No. (%) | ||||||

| Diabetes | 2503 (63.0) | 4712 (65.1) | −4.4 | 1878 (63.3) | 1860 (62.7) | 1.3 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 2824 (71.1) | 3705 (51.2) | 41.7 | 2005 (67.6) | 1957 (66.0) | 3.4 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2601 (65.5) | 3673 (50.7) | 30.2 | 1821 (61.4) | 1770 (59.7) | 3.5 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1560 (39.3) | 2775 (38.3) | 1.9 | 1146 (38.6) | 1133 (38.2) | 0.9 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1030 (25.9) | 2051 (28.3) | −5.4 | 782 (26.4) | 794 (26.8) | −0.9 |

| Paralysis | 75 (1.9) | 197 (2.7) | 5.6 | 54 (1.8) | 68 (2.3) | −3.3 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1873 (47.1) | 2974 (41.1) | 12.2 | 1329 (44.8) | 1316 (44.4) | 0.9 |

| Chronic liver disease | 248 (6.2) | 494 (6.8) | −2.4 | 176 (5.9) | 162 (5.5) | 2.0 |

| Connective tissue disease | 176 (4.4) | 218 (3.0) | 7.5 | 122 (4.1) | 115 (3.9) | 1.2 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 239 (6.0) | 355 (4.9) | 4.9 | 176 (5.9) | 177 (6.0) | −0.1 |

| Cancer other than skin | 1171 (29.5) | 2214 (30.6) | −2.5 | 873 (29.4) | 858 (28.9) | 1.1 |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 104 (2.6) | 224 (3.1) | 2.9 | 82 (2.8) | 76 (2.6) | 1.3 |

| Dementia | 335 (8.4) | 699 (9.7) | −4.3 | 252 (8.5) | 257 (8.7) | −0.6 |

| Depression | 630 (15.9) | 1313 (18.1) | −6.1 | 473 (15.9) | 468 (15.8) | 0.5 |

| PTSD | 109 (2.7) | 336 (4.6) | −10.1 | 92 (3.1) | 94 (3.2) | −0.4 |

| Year of incident kidney failure, No. (%) | ||||||

| 2010-2011 | 2382 (59.9) | 3634 (50.2) | 19.7 | 1727 (58.2) | 1671 (56.3) | 3.8 |

| 2008-2009 | 1592 (41.1) | 3607 (49.8) | 1239 (41.8) | 1295 (43.7) | ||

| Index eGFR, mean (SD), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 29 (13) | 31 (14) | −14.7 | 29 (13) | 29 (12) | −1.0 |

| eGFR at incident kidney failure, mean (SD), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 14 (6) | 13 (4) | 13.9 | 13 (5) | 13 (4) | 0.9 |

| Missing, No. (%) | 514 (12.9) | 156 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | ||

| Rate of eGFR decline prior to ESRD, % | ||||||

| <5 mL/min/1.73 m2/y | 959 (24.1) | 1422 (19.6) | 23.1 | 771 (26.0) | 739 (24.9) | 4.6 |

| 5 to <10 mL/min/1.73 m2/y | 1113 (28.0) | 2062 (28.5) | 960 (32.4) | 925 (31.2) | ||

| ≥10 mL/min/1.73 m2/y | 1388 (34.9) | 3601 (49.7) | 1235 (41.6) | 1302 (43.9) | ||

| Missing | 514 (12.9) | 156 (2.2) | 0 | 0 | ||

| No. of pre-ESRD nephrologist visits, No. (%) | ||||||

| 1 | 580 (14.6) | 1127 (15.6) | 2.7 | 431 (14.5) | 439 (14.8) | 7.6 |

| ≥2 | 3394 (85.4) | 6114 (84.4) | 2535 (85.5) | 2527 (85.2) | ||

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; VA, Veterans Affairs.

Misclassification of Kidney Failure

Although the ascertainment of dialysis treatment using USRDS and dialysis claims has higher than 98% accuracy,20 the claims + laboratory method to ascertain incident kidney failure cases does not capture 23% of patients with incident kidney failure who are not treated with dialysis (eTable 1 in the Supplement). To assess the potential effect of differential misclassification, we recalculated the frequency of dialysis treatment assuming 23% of Medicare patients who were not treated with dialysis were misclassified as nonincident kidney failure cases (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Analyses were conducted from March 15, 2016, through September 20, 2017, using SAS Enterprise Guide, version 7.1 (SAS Institute) and Stata, version 13.1 (StataCorp LP) for data analysis. Findings were significant at P <.05.

Results

Cohort Characteristics

Of the 11 215 patients included in the study, 11 085 (98.8%) were men; mean (SD) age was 79.1 (6.9) years. Patient characteristics according to the site of pre-ESRD nephrology care are presented in Table 1. Compared with patients who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in VA, patients who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare were older and more likely to be male, white, and married. On average, they lived farther from a VA medical center, were more likely to have a copayment for VA services, and to reside in rural areas and areas with a higher median income. They were also more likely to have missing eGFR values at follow-up. After propensity-score matching, the cohort was well balanced on measured characteristics, indicated by standardized differences less than 10%.

Dialysis Treatment in Medicare vs VA

Within 2 years of incident kidney failure, 7071 patients (63.0%) started dialysis. The unadjusted frequency of dialysis treatment was 81.9% among patients who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare, compared with 52.7% among patients who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in VA (adjusted risk difference, 28 percentage points; 95% CI, 26-30 percentage points) (Table 2). In propensity-matched analyses, the results were similar (Table 2). Large differences in the frequency of dialysis treatment between Medicare and VA persisted in analyses restricted to patients with at least 2 pre-ESRD nephrology visits (adjusted risk difference, 27 percentage points; 95% CI, 23-30 percentage points) (eTable 3 in the Supplement) and in analyses restricted to patients with a sustained eGFR of 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 or lower (adjusted risk difference, 12 percentage points; 95% CI, 10-15 percentage points) (eTable 3 in the Supplement). Similarly, when we required a 90-day duration for the low eGFR component of the incident kidney failure, the adjusted risk difference in dialysis initiation between Medicare and VA was 26 percentage points (95% CI, 24-28 percentage points). Among patients who started dialysis, 163 (5.0%) of those who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare started peritoneal dialysis vs hemodialysis, compared with 108 (2.8%) of patients who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in VA (P < .01).

Table 2. Dialysis Treatment Within 2 Years of Incident Kidney Failure Among Patients Receiving Pre-ESRD Nephrology Care in Medicare vs VA.

| Cohort | No. (%) Treated With Dialysis | Risk Difference (95% CI) | Relative Risk (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main (N = 11 215)a | |||

| VA (n = 7241) | 3818 (52.7) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Medicare (n = 3974) | 3253 (81.9) | 28 (26-30) | 1.53 (1.48-1.57) |

| Propensity-matched (n = 5932)b | |||

| VA (n = 2966) | 1509 (50.9) | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Medicare (n = 2966) | 2349 (79.2) | 28 (26-31) | 1.56 (1.50-1.62) |

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; VA, Veterans Affairs.

Models adjusted for age, sex, race, marital status, zip code median income, urban residence, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, cerebrovascular disease, paralysis, chronic pulmonary disease, chronic liver disease, connective tissue disease, peptic ulcer disease, cancer other than skin, metastatic solid tumor, dementia, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, rate of eGFR decline, driving distance, VA co-pay, and year.

Based on a propensity score model that included all variables listed in Table 1. Unadjusted analysis after matching.

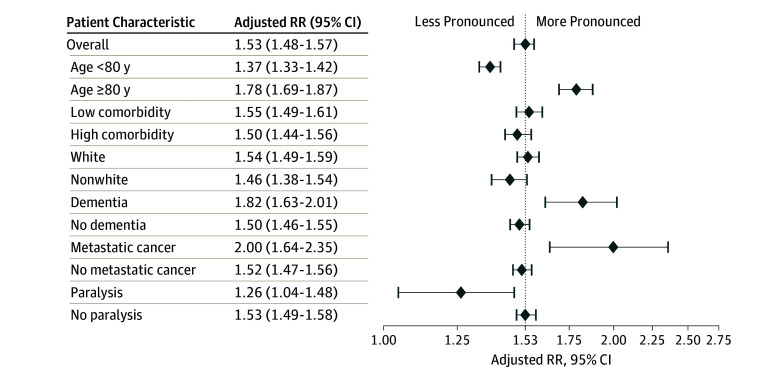

Differences in the frequency of dialysis treatment between Medicare and VA were larger among patients aged 80 years or older and among patients with dementia or metastatic cancer, and less pronounced among patients with paralysis, (all P < .05 for interaction) (Figure 2). There was no evidence of effect modification by race or Charlson Comorbidity Index score.

Figure 2. Relative Risk of Dialysis Treatment Within 2 Years of Incident Kidney Failure Among Patients Receiving Pre–End Stage Renal Disease Nephrology Care Through Medicare vs Veterans Affairs.

Measured in main analytic cohort (N = 11 215) of patients receiving care through Veterans Affairs vs Medicare. The dotted line indicates overall effect of higher dialysis use in Medicare. RR indicates relative risk.

Analyses that assumed differential misclassification of Medicare patients not treated with dialysis as non–kidney failure cases did not substantially change the results. Assuming a misclassification rate of 23% among Medicare patients, the unadjusted frequency of dialysis treatment would drop from 81.9% to 77.3% in this group (eTable 2 in the Supplement). For the frequency of dialysis treatment in Medicare to be similar to that of VA, the kidney failure misclassification rate would need to be 75% among Medicare patients.

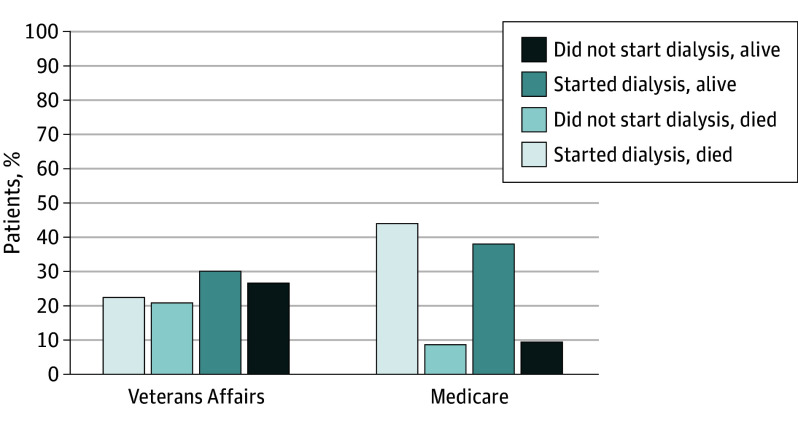

Mortality in Medicare vs VA

Within 2 years of kidney failure, 5280 patients (47.1%) died. Among patients who started dialysis, the mortality rate was 54.3% among patients who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare vs 43.3% among those who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in VA. Among all patients with kidney failure, the mortality rate was 53.2% among patients who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare vs 43.8% among those who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in VA. These differences were attenuated but remained significant after adjustment (adjusted risk difference, 5 percentage points; 95% CI, 3-7 percentage points) (Figure 3). The results were similar in the propensity-matched cohort (adjusted risk difference, 8 percentage points; 95% CI, 5-11 percentage points).

Figure 3. Frequency of Death Within 2 Years of Incident Kidney Failure Among Patients Receiving Pre–End Stage Renal Disease Nephrology Care Through Medicare vs Veterans Affairs.

Measured in main analytic cohort (N = 11 215) of patients receiving care through Veterans Affairs vs Medicare.

Discussion

In a national, contemporary cohort of older veterans with incident kidney failure, patients who received pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare had a markedly higher frequency of dialysis initiation compared with patients who received nephrology care in VA. The difference in initiation of dialysis between Medicare and VA remained robust in subgroup analyses and could not be explained by observed patient characteristics or less frequent pre-ESRD nephrology care in Medicare. Despite more frequent initiation of dialysis, patients who received care in Medicare were not more likely to survive compared with patients who received care in VA.

The results extend a prior study that demonstrated that veterans treated outside of the VA started dialysis earlier in the course of their disease than those treated within the VA.11,21 In the present study, early initiation of dialysis accounted for some, but not all, of the differences in dialysis treatment between VA and Medicare. Our findings are broadly consistent with comparisons of use and quality of care in VA vs Medicare for other serious illnesses. Studies that assessed recommended processes of care have mostly demonstrated that VA groups performed better than non-VA comparison groups.22,23 Studies that assessed risk-adjusted mortality generally found similar rates for VA and non-VA settings.24

Our study may illustrate how differences in the structure and delivery of care can result in marked variation in use of a high-cost treatment with limited or uncertain benefits. These lessons may be applicable to other interventions used in frail, older adults, such as implantable cardiac defibrillators and inferior vena cava filters. Veterans Affairs has an integrated health care system consisting of tertiary care centers, community clinics, and long-term care facilities, all linked by an electronic medical record. Integration of medical records can facilitate care delivery for patients with complex comorbidities who receive multiple health care services, including documentation of patient preferences and goals. The VA’s nephrology workforce comprises salaried physicians who do not have direct financial incentives to use dialysis. In addition, VA has prioritized support for palliative care at an organizational level by funding interdisciplinary palliative care teams in every VA medical center.25 In contrast, in the Medicare fee-for-service system, physicians receive higher reimbursement for dialysis care than for care of patients without dialysis, and they may have ownership or other financial interests in dialysis facilities.26 Because there is no organized infrastructure to deliver supportive care services in the outpatient setting, starting dialysis can simply be the easiest way to address a patient’s complex care needs. Apart from these factors, we could not rule out the possibility that patient preferences for dialysis determine the setting for pre-ESRD care. Prior studies have shown that patient preferences for aggressive care do not vary widely by geography, which was correlated with the site of care.27 Other unmeasured differences between the 2 systems could also potentially explain the findings, but we adjusted for a broad range of sociodemographic and clinical variables known to be associated with our outcomes. Fee-for-service practitioners are more incentivized to completely code comorbidities than are those in VA; such differential coding practices would bias our findings to the null.

Counter to conventional wisdom, more frequent initiation of dialysis in Medicare did not translate into improved overall survival. If sicker patients were preferentially receiving care in Medicare, one might expect lower frequency of dialysis initiation in Medicare. In fact, more frequent dialysis initiation among Medicare vs VA patients was even more pronounced among subgroups that are less likely to realize a survival benefit from dialysis: patients aged 80 years or older, patients with dementia, and patients with metastatic cancer.28 Provision of dialysis in an older, frail patient is frequently viewed as a trade-off between quantity and quality of life, and in this context its use is commonly not considered overuse unless it is inconsistent with patient preferences.29 While in some instances patient preferences reflect deeply held values, in others they reflect lack of information about the potential harms of dialysis or alternative treatment options.30,31 Collectively, these results emphasize the importance of a more balanced presentation of risks along with benefits during dialysis decision making.

Capitated payment systems, such as in the VA, are vulnerable to criticism that they may restrict access to potentially beneficial services. Yet as our study and others demonstrate, recent policy changes intended to expand access to non-VA care may have unintended consequences if care is not coordinated across health care systems.32,33 Future studies should evaluate whether increasing subspecialty care services in VA community-based outpatient clinics or expanded use of telehealth for subspecialty care improves care quality and outcomes compared with non-VA care.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths, including the large national sample of veterans and the use of analytical methods to account for confounding by indication. There are also several limitations. Our estimates of the difference in initiation of dialysis treatment between Medicare and VA lacked precision due to uncertainty in the number of incident kidney failure cases without dialysis in Medicare. Nevertheless, we demonstrate that the differences that we observed are unlikely to be explained by ascertainment bias alone. We were unable to determine patient preferences for dialysis and the extent to which preferences influenced the setting of pre-ESRD care. Similarly, we could not evaluate patient satisfaction with care. The results may not be generalizable to younger veterans or nonveterans. Finally, because this was an observational study, the results are susceptible to confounding. One way in which we mitigate this issue is through an analysis that incorporates propensity scores in the design, which yielded qualitatively similar results. Even so, the possibility of unmeasured confounding remains, as we could not measure other determinants of access to care, such as the availability of transportation and waiting time.

Conclusions

Dialysis appears to be the default treatment option for the majority of older veterans who receive pre-ESRD care in Medicare, but this pattern of care was not associated with better overall survival. Additional studies may help to determine the specific processes of care associated with these findings and whether they can be replicated among the rapidly growing number of integrated delivery systems outside of the VA.

eMethods. Expanded Methodology

eTable 1. Prevalence, Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV) and Negative Predictive Value (NPV) of Medicare and/or VA Diagnosis Claims Alone or in Combination With a Single eGFR Measurement <15 ml/min/1.73m2, for Identifying Patients With a Sustained eGFR<15 ml/min/1.73m2

eTable 2. Percentage of Incident Kidney Failure Patients Treated With Dialysis, Assuming Differential Misclassification Among Patients Who Received pre-ESRD Nephrology Care in Medicare or in Neither Health Care System

eTable 3. Dialysis Treatment Within Two Years of Incident Kidney Failure in VA Versus Medicare, Among Patient Subgroups

eTable 4. Dialysis Treatment Within Two Years Of Incident Kidney Failure Among Patients Receiving pre-ESRD Nephrology Care in VA, Medicare, Dual-Users, and Those Who Received Nephrology Care in Neither Health Care System

References

- 1.Williams AW, Dwyer AC, Eddy AA, et al. ; American Society of Nephrology Quality, and Patient Safety Task Force . Critical and honest conversations: the evidence behind the “Choosing Wisely” campaign recommendations by the American Society of Nephrology. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(10):1664-1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1539-1547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carson RC, Juszczak M, Davenport A, Burns A. Is maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(10):1611-1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moss AH. Revised dialysis clinical practice guideline promotes more informed decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(12):2380-2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Hare AM, Rodriguez RA, Hailpern SM, Larson EB, Kurella Tamura M. Regional variation in health care intensity and treatment practices for end-stage renal disease in older adults. JAMA. 2010;304(2):180-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson BM, Akizawa T, Jager KJ, Kerr PG, Saran R, Pisoni RL. Factors affecting outcomes in patients reaching end-stage kidney disease worldwide: differences in access to renal replacement therapy, modality use, and haemodialysis practices. Lancet. 2016;388(10041):294-306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United States Renal Data System . 2014 USRDS Annual Data Report: An Overview of the Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hynes DM, Stroupe KT, Fischer MJ, et al. ; for ESRD Cost Study Group . Comparing VA and private sector healthcare costs for end-stage renal disease. Med Care. 2012;50(2):161-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer MJ, Stroupe KT, Kaufman JS, et al. Predialysis nephrology care among older veterans using Department of Veterans Affairs or Medicare-covered services. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(2):e57-e66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang V, Maciejewski ML, Patel UD, Stechuchak KM, Hynes DM, Weinberger M. Comparison of outcomes for veterans receiving dialysis care from VA and non-VA providers. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu MK, O’Hare AM, Batten A, et al. Trends in timing of dialysis initiation within versus outside the Department of Veterans Affairs. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(8):1418-1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. ; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) . A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604-612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hemmelgarn BR, James MT, Manns BJ, et al. ; Alberta Kidney Disease Network . Rates of treated and untreated kidney failure in older vs younger adults. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2507-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wald R, Quinn RR, Luo J, et al. ; University of Toronto Acute Kidney Injury Research Group . Chronic dialysis and death among survivors of acute kidney injury requiring dialysis. JAMA. 2009;302(11):1179-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):199-200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muller CJ, MacLehose RF. Estimating predicted probabilities from logistic regression: different methods correspond to different target populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(3):962-970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bergstralh E, Kosanke J. Locally written SAS Macros: Match 1 or more controls to cases using the GREEDY algorithm. 2004. http://www.mayo.edu/research/departments-divisions/department-health-sciences-research/division-biomedical-statistics-informatics/software/locally-written-sas-macros. Accessed May 8, 2017.

- 20.Wong SP, Hebert PL, Laundry RJ, et al. Decisions about renal replacement therapy in patients with advanced kidney disease in the US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2000-2011. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(10):1825-1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper BA, Branley P, Bulfone L, et al. ; IDEAL Study . A randomized, controlled trial of early versus late initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7):609-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, Earle CC, Bozeman SR, McNeil BJ. End-of-life care for older cancer patients in the Veterans Health Administration versus the private sector. Cancer. 2010;116(15):3732-3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keating NL, Landrum MB, Lamont EB, et al. Quality of care for older patients with cancer in the Veterans Health Administration versus the private sector: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(11):727-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trivedi AN, Matula S, Miake-Lye I, Glassman PA, Shekelle P, Asch S. Systematic review: comparison of the quality of medical care in Veterans Affairs and non-Veterans Affairs settings. Med Care. 2011;49(1):76-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs . Hospice and Palliative Care 2011 Annual Report. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bennett WM. Ethical conflicts for physicians treating ESRD patients. Semin Dial. 2004;17(1):1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barnato AE, Herndon MB, Anthony DL, et al. Are regional variations in end-of-life care intensity explained by patient preferences? a study of the US Medicare population. Med Care. 2007;45(5):386-393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussain JA, Mooney A, Russon L. Comparison of survival analysis and palliative care involvement in patients aged over 70 years choosing conservative management or renal replacement therapy in advanced chronic kidney disease. Palliat Med. 2013;27(9):829-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipitz-Snyderman A, Bach PB. Overuse of health care services: when less is more … more or less. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(14):1277-1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):195-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song MK, Lin FC, Gilet CA, Arnold RM, Bridgman JC, Ward SE. Patient perspectives on informed decision-making surrounding dialysis initiation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(11):2815-2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gellad WF, Zhao X, Thorpe CT, Mor MK, Good CB, Fine MJ. Dual use of Department of Veterans Affairs and Medicare benefits and use of test strips in veterans with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(1):26-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thorpe JM, Thorpe CT, Gellad WF, et al. Dual health care system use and high-risk prescribing in patients with dementia: a national cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(3):157-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Expanded Methodology

eTable 1. Prevalence, Sensitivity, Specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV) and Negative Predictive Value (NPV) of Medicare and/or VA Diagnosis Claims Alone or in Combination With a Single eGFR Measurement <15 ml/min/1.73m2, for Identifying Patients With a Sustained eGFR<15 ml/min/1.73m2

eTable 2. Percentage of Incident Kidney Failure Patients Treated With Dialysis, Assuming Differential Misclassification Among Patients Who Received pre-ESRD Nephrology Care in Medicare or in Neither Health Care System

eTable 3. Dialysis Treatment Within Two Years of Incident Kidney Failure in VA Versus Medicare, Among Patient Subgroups

eTable 4. Dialysis Treatment Within Two Years Of Incident Kidney Failure Among Patients Receiving pre-ESRD Nephrology Care in VA, Medicare, Dual-Users, and Those Who Received Nephrology Care in Neither Health Care System