Key Points

Question

Is the association of increased lipoprotein(a) and oxidized phospholipid levels with a faster rate of calcific aortic valve stenosis progression a linear or a threshold association?

Findings

In a secondary analysis of the ASTRONOMER trial following up a cohort of 220 patients with mild to moderate aortic stenosis, a significant linear association was found between plasma levels of lipoprotein(a) and oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein B and apolipoprotein(a) and a faster rate of aortic stenosis progression.

Meanings

By documenting the linear association of lipoprotein(a) and its content of oxidized phospholipids with faster progression of calcific aortic stenosis, this study has pathophysiological and clinical implications for these patients.

This secondary analysis of the ASTRONOMER randomized clinical trial assesses whether plasma levels of lipoprotein(a) have a linear or a threshold association with rate of progression among patients with calcific aorta valve stenosis.

Abstract

Importance

Several studies have reported an association of levels of lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]) and the content of oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein B (OxPL-apoB) and apolipoprotein(a) (OxPL-apo[a]) with faster calcific aortic valve stenosis (CAVS) progression. However, whether this association is threshold or linear remains unclear.

Objective

To determine whether the plasma levels of Lp(a), OxPL-apoB, and OxPL-apo(a) have a linear association with a faster rate of CAVS progression.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial tested the association of baseline plasma levels of Lp(a), OxPL-apoB, and OxPL-apo(a) with the rate of CAVS progression. Participants were included from the ASTRONOMER (Effects of Rosuvastatin on Aortic Stenosis Progression) trial, a multicenter study conducted in 23 Canadian sites designed to test the effect of statin therapy (median follow-up, 3.5 years [interquartile range, 2.9-4.5 years]). Patients with mild to moderate CAVS defined by peak aortic jet velocity ranging from 2.5 to 4.0 m/s were recruited; those with peak aortic jet velocity of less than 2.5 m/s or with an indication for statin therapy were excluded. Data were collected from January 1, 2002, through December 31, 2005, and underwent ad hoc analysis from April 1 through September 1, 2018.

Interventions

After the randomization process, patients were followed up by means of echocardiography for 3 to 5 years.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Progression rate of CAVS as assessed by annualized progression of peak aortic jet velocity.

Results

In this cohort of 220 patients (60.0% male; mean [SD] age, 58 [13] years), a linear association was found between plasma levels of Lp(a) (odds ratio [OR] per 10-mg/dL increase, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.03-1.19; P = .006), OxPL-apoB (OR per 1-nM increase, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.01-1.12; P = .02), and OxPL-apo(a) (OR per 10-nM increase, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.27; P = .002) and faster CAVS progression, which is marked in younger patients (OR for Lp[a] level per 10-mg/dL increase, 1.19 [95% CI, 1.07-1.33; P = .002]; OR for OxPL-apoB level per 1-nM increase, 1.06 [95% CI, 1.02-1.17; P = .01]; and OR for OxPL-apo[a] level per 10-nM increase, 1.26 [95% CI, 1.10-1.45; P = .001]) and remained statistically significant after comprehensive multivariable adjustment (β coefficient, ≥ 0.25; SE, ≤ 0.004 [P ≤ .005]; OR, ≥1.10 [P ≤ .007]).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study demonstrates that the association of Lp(a) levels and its content in OxPL with faster CAVS progression is linear, reinforcing the concept that Lp(a) levels should be measured in patients with mild to moderate CAVS to enhance management and risk stratification.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00800800

Introduction

Calcific aortic valve stenosis (CAVS) is the most common valvular heart disease.1 At present, no medical treatment is available for these patients, and the only remaining option is to perform an aortic valve replacement.2 Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the LPA gene have been identified as the only genome-wide significant single-nucleotide polymorphisms to be associated with CAVS.3,4,5 Furthermore, plasma levels of lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]) and its associated content in oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein B (OxPL-apoB) and apolipoprotein(a) (OxPL-apo[a]) are indicative of hemodynamic progression of CAVS and higher risk of aortic valve replacement.6 The role of OxPL in aortic valve disease has recently been corroborated by the comprehensive analysis of a transgenic mouse model, where overexpression of the antibody E06 resulted in reduced aortic valve calcification and reduced peak gradient.7 However, whether this association is threshold or linear remains unclear. Using data from the ASTRONOMER (Effects of Rosuvastatin on Aortic Stenosis Progression) trial, we tested the hypothesis that Lp(a), OxPL-apoB, and OxPL-apo(a) plasma levels were linearly associated with a faster rate of CAVS progression.

Methods

Patient Population

The design and main results of the ASTRONOMER trial have been previously reported.8 The ASTRONOMER trial included adults (age range, 18-82 years) with mild to moderate aortic stenosis at baseline (peak aortic jet velocity [Vpeak], 2.5-4.0 m/s) recruited in 23 Canadian sites from January 1, 2002, through December 31, 2005. Exclusion criteria were severe or symptomatic AS, severe aortic regurgitation, significant mitral valve disease (ie, mitral stenosis or regurgitation), symptomatic coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, diabetes, or the need for treatment to lower low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels. Patients were randomized to rosuvastatin calcium, 40 mg, vs placebo. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at all participating centers, and patients gave written informed consent.

Clinical, Laboratory, and Doppler Echocardiographic Data

Clinical, laboratory, and Doppler echocardiographic data for the ASTRONOMER trial have been described previously (eMethods in the Supplement).6,9 Briefly, clinical data included age, sex, anthropometric data, and comorbidities. In a fasting sample of plasma collected at baseline and stored at −80°C, levels of OxPL-apoB, OxPL-apo(a), and Lp(a) were subsequently measured in a subset of 220 patients from the ASTRONOMER trial in an ad hoc secondary analysis. The main Doppler echocardiographic index used to assess CAVS severity was Vpeak.

Study Outcome

The outcome variable was the progression rate of valve stenosis measured as annualized changes in Vpeak. To account for different follow-up lengths, annualized changes in Vpeak were calculated by dividing the difference between last follow-up and baseline values by the length of follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from April 1 through September 1, 2018. Continuous data were expressed as mean (SD). One-way analysis of variance, followed by a post hoc Tukey test, was used to compare the progression rate of CAVS across patient groups with increasing plasma levels of Lp(a), including the reference group (as previously published6) with Lp(a) levels of less than 60 mg/dL (n = 149) vs the group with Lp(a) levels of 60 to 100 mg/dL (group 1 [n = 43]) and the group with Lp(a) levels of greater than 100 mg/dL (group 2 [n = 28]) (to approximate Lp[a] levels to nanomoles per liter, multiply by 2.5). The cutoff values used to determine groups for OxPL-apoB and OxPL-apo(a) levels were defined to have the same number of patients in each group (ie, 149 in the reference group, 43 in group 1, and 28 in group 2). Cutoffs then used included 5.8 and 13.0 nM for OxPL-apoB and 36.0 and 72.0 nM for OxPL-apo(a). Univariable and multivariable linear regression analyses were performed to identify the independent indicators of CAVS progression as annualized progression rates of peak aortic jet velocity. Baseline plasma levels of Lp(a), OxPL-apoB, and OxPL-apo(a) were entered in these models in continuous format. As previously described,6 the multivariable model included the following variables: (1) variables with P < .10 in individual analysis (ie, metabolic syndrome, systolic blood pressure, apoB level, creatinine level, baseline aortic valve calcification score, baseline peak aortic jet velocity, and valvuloarterial impedance), (2) traditional cardiovascular risk factors (ie, age, male sex, history of hypertension, corrected low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level [the difference between low-density lipoprotein cholesterol level and Lp[a] mass in milligrams per deciliter multiplied by 0.3], and history of smoking), (3) aortic valve phenotype (bicuspid vs tricuspid), and (4) randomization status (statin vs placebo). Results were reported as standardized β coefficient (standard error [SE]). Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were also performed to identify the risk of rapid progress, defined as an annualized progression rate of Vpeak of at least 0.20 m/s per year as previously described.6 Results were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Levels of Lp(a), OxPL-apoB, and OxPL-apo(a) were not included in the same model owing to their strong correlation (r > 0.85 for all), resulting in a high level of multicollinearity (ie, variance inflation factor >5). Two-tailed P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline clinical, laboratory, and Doppler echocardiographic characteristics of the studied population were previously reported.6 We reported the main characteristics in Table 1. Of the 220 included patients, 132 (60.0%) were men and 88 (40.0%) were women; mean age was 58 (13) years. One hundred twelve participants (50.9%) were randomized to statin therapy. The median level of Lp(a) was 29.8 mg/dL (interquartile range [IQR], 12.1-76.1 mg/dL); median level of OxPL-apoB, 3.47 nM (IQR, 2.26-8.64 nM); and median level of OxPL-apo(a), 15.7 nM (IQR, 4.5-51.7 nM). At baseline, the mean peak aortic jet velocity was 3.2 (0.4) m/s, and 105 (47.7%) had a bicuspid aortic valve. The median follow-up was 3.5 years (IQR, 2.9-4.5 years). There was no difference in clinical and Doppler echocardiographic data, and especially regarding the baseline severity of aortic stenosis, across the 3 groups of Lp(a) plasma levels (Table 1). As expected, the only laboratory markers that reached significance levels were corrected levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (reference group, 123 [26] mg/dL; group 1, 126 [28] mg/dL; and group 2, 139 [31] mg/dL [P = .02]), apoB levels (reference group, 100 [17] mg/dL; group 1, 101 [21] mg/dL; and group 2, 111 [19] mg/dL [P = .02]), and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels (reference group, 56 [16] mg/dL; group 1, 61 [17] mg/dL; and group 2, 62 [20 mg/dL [P = .04]) (to convert cholesterol to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259; apoB to grams per liter, multiply by 0.01). Similar findings were observed across the 3 groups for OxPL-apoB and OxPL-apo(a).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Patients According to Lp(a) Plasma Levels.

| Variable | Lp(a) Level, mg/dL | P Valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 220) | <60 (n = 149) | 60-100 (n = 43) | >100 (n = 28) | ||

| Clinical | |||||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 58 (13) | 57 (14) | 59 (12) | 59 (11) | .53 |

| Male, No. (%) | 132 (60.0) | 91 (61.1) | 26 (60.5) | 15 (54.6) | .76 |

| Body surface area, mean (SD), m2 | 1.91 (0.21) | 1.91 (0.21) | 1.91 (0.21) | 1.88 (0.23) | .68 |

| Metabolic syndrome, No. (%) | 59 (26.8) | 44 (29.5) | 12 (27.9) | 3 (10.7) | .14 |

| History of hypertension, No. (%) | 70 (31.8) | 44 (29.5) | 15 (34.9) | 11 (39.3) | .53 |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | |||||

| Systolic | 127 (17) | 128 (18) | 127 (14) | 121 (15) | .17 |

| Diastolic | 75 (10) | 76 (10) | 74 (10) | 73 (11) | .24 |

| History of smoking, No. (%) | 101 (45.9) | 75 (50.3) | 21 (48.8) | 12 (42.9) | .77 |

| Laboratory data | |||||

| LDL-C level, mean (SD), mg/dL | 126 (27) | 123 (26) | 126 (28) | 139 (31)b | .02 |

| Corrected LDL-C level, mean (SD), mg/dLc | 116 (27) | 120 (26) | 107 (28)b | 106 (28)b | .002 |

| ApoB level, mean (SD), mg/dL | 102 (19) | 100 (17) | 101 (21) | 111 (19)b | .02 |

| HDL-C level, mean (SD), mg/dL | 57 (16 | 56 (16) | 61 (17) | 62 (20) | .04 |

| Triglyceride level, mean (SD), mg/dL | 120 (60) | 122 (61) | 123 (64) | 102 (47) | .28 |

| Fasting glucose level, mean (SD), mg/dL | 95 (11) | 95 (12) | 94 (9) | 93 (9) | .52 |

| Creatinine level, mean (SD), mg/dL | 0.91 (0.19) | 0.92 (0.18) | 0.89 (0.21) | 0.88 (0.19) | .53 |

| Lp(a) level, median (IQR) | 29.8 (12.1-76.1) | 18.5 (8.9-30.0) | 78.7 (71.2-88.5) | 106 (102-119) | NA |

| Doppler echocardiographic data | |||||

| Bicuspid aortic valve, No. (%) | 105 (47.7) | 69 (46.3) | 19 (44.2) | 17 (60.7) | .33 |

| Aortic valve calcification score, mean (SD) | 1.7 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.7) | 1.8 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.5) | .17 |

| Peak aortic jet velocity, mean (SD), m/s | 3.2 (0.4) | 3.2 (0.4) | 3.1 (0.4) | 3.1 (0.4) | .13 |

| Transvalvular gradient, mean (SD), mm Hg | 22 (7) | 23 (7) | 22 (7) | 21 (7) | .28 |

| Indexed aortic valve area, mean (SD), cm2/m2 | 0.70 (0.20) | 0.71 (0.2)1 | 0.68 (0.17) | 0.70 (0.20) | .84 |

| Valvuloarterial impedance, mean (SD), mm Hg/ml.m2.04 | 4.9 (1.5) | 4.9 (1.6) | 4.9 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.2) | .99 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, mean (SD), % | 66 (6) | 65 (6) | 67 (8) | 67 (7) | .25 |

Abbreviations: ApoB, apolipoprotein B; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IQR, interquartile range; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); NA, not applicable.

Calculated from analysis of variance.

Indicates P < .05, Tukey post hoc test, compared with the reference group (Lp[a] level <60 mg/dL).

Corrected for the cholesterol content in Lp(a) using the following formula: corrected LDL-C Level = [LDL-C Level – Lp(a) Mass (in mg/dL)] × 0.3.6

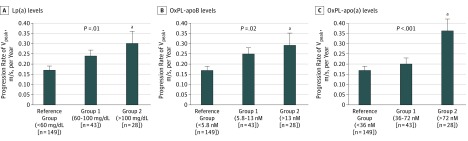

Patients with increasing Lp(a), OxPL-apoB, or OxPL-apo(a) levels showed a stepwise increase in the rate of CAVS progression (Figure) from a mean (standard error of the mean) of 0.17 (0.02) m/s per year in the reference group for all 3 measures to 0.26 (0.03) m/s per year for Lp(a) level, 0.25 (0.03) m/s per year for OxPL-apoB level, and 0.20 (0.03) m/s per year for OxPL-apo(a) level in group 1. Compared with the reference group, patients in the group 2 had a significantly faster CAVS progression for increasing levels of Lp(a) (0.30 [0.06] m/s per year [P = .02, Tukey post hoc test), OxPL-apoB (0.29 [0.06] m/s per year [P = .04, Tukey post hoc test), and OxPL-apo(a) (0.36 [0.06] m/s per year [P < .001, Tukey post hoc test).

Figure. Rate of Calcific Aortic Valve Stenosis Progression by Increasing Plasma Levels of Lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]) and Its Oxidized Phospholipids.

Annualized progression rate of peak aortic jet velocity (Vpeak; calculated by dividing the difference between last follow-up and baseline values by the length of follow-up) was compared according to increasing levels of Lp(a) and its associated content in oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein B-100 (OxPL-apoB) and apolipoprotein(a) (OxPL-apo[a]). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). P values for between-group comparison are calculated using analysis of variance.

aP < .05 vs reference group, Tukey post hoc test.

Plasma levels of Lp(a) (β coefficient, 0.18; SE, 0.001; P = .006), OxPL-apoB (β coefficient, 0.21; SE, 0.003; P = .002), and OxPL-apo(a) (β coefficient, 0.20; SE, 0.001; P = .003) were significantly associated with faster CAVS progression rate (Table 2). After comprehensive multivariable adjustment, plasma levels of Lp(a) (β coefficient, 0.26; SE, 0.004; P = .003), OxPL-apoB (β coefficient, 0.28; SE, 0.003; P = .001), and OxPL-apo(a) (β coefficient, 0.25; SE, 0.001; P = .005) were independently associated with CAVS progression rate (Table 2). The use of logarithm transformation of Lp(a), OxPL-apoB, or OxPL-apo(a) levels instead of their absolute values provided consistent results (eTable in the Supplement).

Table 2. Linear Association of Lp(a) and Its Content on Oxidized Phospholipids With Rate of CAVS Progression.

| Association | All Patients (N = 220) | Patients Aged ≤57 y (n = 108) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariable | P Value | Multivariable | P Value | Univariable | P Value | Multivariable | P Value | |

| CAVS Progression Rate, β Coefficient (SE)a | ||||||||

| Lp(a) level | 0.18 (0.001) | .006 | 0.26 (0.004) | .003 | 0.30 (0.001) | .002 | 0.43 (0.001) | .001 |

| OxPL-apoB level | 0.21 (0.003) | .002 | 0.28 (0.003) | .001 | 0.32 (0.004) | .001 | 0.47 (0.004) | <.001 |

| OxPL-apo(a) level | 0.20 (0.001) | .003 | 0.25 (0.001) | .005 | 0.30 (0.001) | .001 | 0.46 (0.001) | <.001 |

| Risk of Rapid CAVS Progression, OR (95% CI)b | ||||||||

| Lp(a) level per 10-mg/dL increase | 1.10 (1.03-1.19) | .006 | 1.14 (1.05-1.24) | .002 | 1.19 (1.07-1.33) | .002 | 1.28 (1.10-1.48) | .001 |

| OxPL-apoB level per 1-nM increase | 1.06 (1.01-1.12) | .02 | 1.10 (1.03-1.16) | .002 | 1.09 (1.02-1.17) | .01 | 1.13 (1.03-1.25) | .007 |

| OxPL-apo(a) level per 10-nM increase | 1.16 (1.05-1.27) | .002 | 1.22 (1.09-1.36) | <.001 | 1.26 (1.10-1.45) | .001 | 1.41 (1.16-1.73) | .001 |

Abbreviations: apo(a), apolipoprotein(a); apoB, apolipoprotein B; CAVS, calcific aortic valve stenosis; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Lp(a), lipoprotein(a); OR, odds ratio; OxPL, oxidized phospholipids.

Defined by the annualized progression of peak aortic jet velocity (Vpeak). Data are expressed as β coefficient (standardized raw-score regression coefficient) and SE from the linear regression analysis of the progression rate of CAVS (ie, annualized Vpeak). The multivariable model for all patients was adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, smoking history, metabolic syndrome, systolic blood pressure, statin use, corrected LDL-C level, apoB level, creatinine level, bicuspid aortic valve phenotype, aortic valve calcification score, baseline peak aortic jet velocity, and valvuloarterial impedance. The multivariable model for patients 57 years or younger was adjusted for the same variables as for all patients, except that age and smoking history were not included.

Defined as annualized Vpeak of greater than 0.20 m/s per year. Odds ratios and 95% CIs are calculated from the logistic regression analysis of the rapid progression rate of CAVS. Each multivariable model includes 1 metabolic variable and is adjusted for confounding variables as previously published.6 The multivariable model for all patients was adjusted for age, sex, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, statin use, corrected LDL-C level, creatinine level, bicuspid aortic valve phenotype, aortic valve calcification score, and baseline peak aortic jet velocity. The multivariable model for patients 57 years or younger was adjusted for the same variables as for all patients, except for age.

In the subset of 108 patients 57 years or younger (ie, median age for the cohort), the association between CAVS progression rate and Lp(a), OxPL-apoB, and OxPL-apo(a) levels in continuous format was also significant in univariable and after comprehensive multivariable adjustment (β coefficient, ≥ 0.43; SE, ≤ 0.004; P ≤ .01 for all) (Table 2 and eTable in the Supplement). When we analyzed the risk of rapid progress, defined as annualized Vpeak of greater than 0.20 m/s per year, there was a significant association for levels of Lp(a) (OR per 10-mg/dL increase, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.03-1.19; P = .006), OxPL-apoB (OR per 1-nM increase, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.01-1.12; P = .02), and OxPL-apo(a) (OR per 10-nM increase, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.05-1.27; P = .002). The association remained significant after multivariable adjustment for levels of Lp(a) (OR per 10-mg/dL increase, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.10-1.48; P = .001), OxPL-apoB (OR per 1-nM increase, 1.13; 95% CI, 1.03-1.25; P = .007), and OxPL-apo(a) (OR per 10-nM increase, 1.41; 95% CI, 1.16-1.73; P = .002) (Table 2). Similar to the previous analysis, the analysis of Lp(a), OxPL-apoB, and OxPL-apo(a) levels after logarithm transformation (eTable in the Supplement) or in the subset of younger patients (ie, ≤57 years old) (Table 2) provided consistent results.

Discussion

This study documents that in patients with preexisting mild to moderate CAVS, the association of Lp(a), OxPL-apoB, and OxPL-apo(a) with more rapid progression of CAVS is linear, as measured by continually increasing Vpeak. These data add to the increasing database that Lp(a) is not only associated with prevalent aortic valve calcification, but also with rapid progression of preexisting CAVS. These data are clinically relevant in the care of these patients, in that rapid progression may be identified easily with a plasma biomarker that may be causal in the pathway of the development and progression of CAVS. Furthermore, the parallel association of OxPL-apoB and OxPL-apo(a), biomarkers that primarily reflect the OxPL content on Lp(a), suggests that the OxPL carried by Lp(a) may be responsible for the proinflammatory and procalcifying effects of Lp(a) in CAVS.10,11,12,13

This study has pathophysiological and clinical implications in the surveillance of patients with mild to moderate CAVS. First, it supports the causality of Lp(a) and OxPL in CAVS7 and documents a linear association with progression of preexisting CAVS. Second, it identifies a group of patients with an exceedingly high progression rate, at approximately 0.30 to 0.35 m/s per year, who would need more frequent surveillance of progression. Third, it supports the measurement of at least 1 Lp(a) level in patients with CAVS. With the high prevalence (approximately 35%) of elevated Lp(a) levels (>30 mg/dL)14 and the development of potent therapies to lower Lp(a) levels15 and methods to inactivate OxPL,7 these findings may influence the design of future intervention trials in patients with CAVS.

Limitations

Study limitations include that these patients were relatively young and had mild to moderate AS. Whether these findings apply to older patients with severe AS remains to be determined.

Conclusions

In patients with preexisting CAVS, the levels of Lp(a), OxPL-apoB, and OxPL-apo(a) may allow estimation of the rate of progression that can be expected. These data need to be validated in larger data sets to define the potential role of surveillance in clinical care.

eMethods. Data Collection

eTable. Linear Association of Logarithmic-Transformed Lp(a), OxPL-apoB, and OxPL-apo(a) Plasma Levels With CAVS Progression Rate

eAppendix. Investigators and Sites of the ASTRONOMER Trial

References

- 1.Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN, Gottdiener JS, Scott CG, Enriquez-Sarano M. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet. 2006;368(9540):1005-1011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69208-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishimura RA, Otto CM, Bonow RO, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC focused update of the 2014 AHA/ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(2):252-289. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen HY, Dufresne L, Burr H, et al. Association of LPA variants with aortic stenosis: a large-scale study using diagnostic and procedural codes from electronic health records. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(1):18-23. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2017.4266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kamstrup PR, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG. Elevated lipoprotein(a) and risk of aortic valve stenosis in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(5):470-477. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cairns BJ, Coffey S, Travis RC, et al. A replicated, genome-wide significant association of aortic stenosis with a genetic variant for lipoprotein(a): meta-analysis of published and novel data. Circulation. 2017;135(12):1181-1183. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Capoulade R, Chan KL, Yeang C, et al. Oxidized phospholipids, lipoprotein(a), and progression of calcific aortic valve stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(11):1236-1246. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Que X, Hung M-Y, Yeang C, et al. Oxidized phospholipids are proinflammatory and proatherogenic in hypercholesterolaemic mice. Nature. 2018;558(7709):301-306. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0198-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan KL, Teo K, Dumesnil JG, Ni A, Tam J; ASTRONOMER Investigators . Effect of lipid lowering with rosuvastatin on progression of aortic stenosis: results of the aortic stenosis progression observation: Measuring Effects of Rosuvastatin (ASTRONOMER) trial. Circulation. 2010;121(2):306-314. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.900027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capoulade R, Clavel MA, Dumesnil JG, et al. ; ASTRONOMER Investigators . Impact of metabolic syndrome on progression of aortic stenosis: influence of age and statin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(3):216-223. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamstrup PR, Hung MY, Witztum JL, Tsimikas S, Nordestgaard BG. Oxidized phospholipids and risk of calcific aortic valve disease: the Copenhagen General Population Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2017;37(8):1570-1578. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leibundgut G, Scipione C, Yin H, et al. Determinants of binding of oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein (a) and lipoprotein (a). J Lipid Res. 2013;54(10):2815-2830. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M040733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torzewski M, Ravandi A, Yeang C, et al. Lipoprotein(a) associated molecules are prominent components in plasma and valve leaflets in calcific aortic valve stenosis. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2017;2(3):229-240. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouchareb R, Mahmut A, Nsaibia MJ, et al. Autotaxin derived from lipoprotein(a) and valve interstitial cells promotes inflammation and mineralization of the aortic valve. Circulation. 2015;132(8):677-690. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varvel S, McConnell JP, Tsimikas S. Prevalence of elevated Lp(a) mass levels and patient thresholds in 532 359 patients in the United States. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2016;36(11):2239-2245. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.116.308011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viney NJ, van Capelleveen JC, Geary RS, et al. Antisense oligonucleotides targeting apolipoprotein(a) in people with raised lipoprotein(a): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trials. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2239-2253. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31009-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Data Collection

eTable. Linear Association of Logarithmic-Transformed Lp(a), OxPL-apoB, and OxPL-apo(a) Plasma Levels With CAVS Progression Rate

eAppendix. Investigators and Sites of the ASTRONOMER Trial