Abstract

Objective: To retrospectively evaluate the results of operative treatment of transtectal transverse fractures of the acetabulum.

Methods: From May 1990 to July 2006, 40 patients with displaced transtectal transverse fracture of the acetabulum were treated surgically. A mean postoperative follow‐up of 88.6 months' (range, 16–121 months) was achieved in 37 patients. Final clinical results were evaluated by a modified Merle d'Aubigné and Postel grading system. Postoperative radiographic results were evaluated by the Matta criteria. Fracture and radiographic variables were analyzed to identify possible associations with clinical outcome.

Results: Fracture reduction was graded as anatomic in 31 patients, imperfect in 4 and unsatisfactory in 2. Two hips were diagnosed to have subtle instability by postoperative radiography. The clinical outcome was graded as excellent in 16 patients, good in 14, fair in 4 and poor in 3. The radiographic result was graded as excellent in 14 patients, good in 15, fair in 4 and poor in 4. There was a strong association between the final clinical and radiographic outcomes. Variables identified as risk factors for unsatisfactory results included residual displacement greater than 2 mm, comminuted fracture of the weight bearing dome, postoperative subtle hip instability and damage to the cartilage of the femoral head.

Conclusion: The uncomplicated radiographic appearance of transtectal transverse fracture belies its complexity. Comminuted fracture of the weight bearing dome, unsatisfactory fracture reduction, subtle hip instability and damage to the cartilage of the femoral head are risk factors for the clinical outcome of transtectal transverse fracture of the acetabulum.

Keywords: Hip fractures; Acetabulum; Fracture fixation, internal; Risk factors

Introduction

Transverse fracture, which splits the innominate bone through the acetabulum into upper iliac and lower ischiopubic fragments, is the most common type of acetabular fracture and has been classified by Letournel and Judet as one of the elementary fracture types. Previously, orthopaedic surgeons have suggested that transverse acetabular fracture, with its simple appearance on plain radiograph, was easy to treat and had a satisfactory clinical outcome 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 . However, more recently, several relevant reports have demonstrated that, rather than being a single simple fracture type, transtectal transverse fracture is often associated with comminuted fracture of the acetabular roof or femoral head damage, which leads to less favorable results 6 , 7 , 8 .

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the results of open reduction and internal fixation of transtectal transverse fracture of the acetabulum, and to discuss the risk factors for an unsatisfactory clinical outcome.

Materials and methods

From May 1990 to July 2006, open reduction and internal fixation were performed on 471 acetabular fractures in 471 patients, including 40 patients with transtectal transverse fracture. Thirty‐seven of these patients were followed up. The remaining three cases could not be contacted for additional evaluation because of changes in address or telephone number.

All of the 37 transtectal transverse fractures, involving 26 men and 11 women, were unilateral. The mean age at surgery was 34 years (range, 22–64 years), and the mean follow‐up period was 88.6 months (range, 16–121 months). The cause of the injury was a traffic accident for 29 patients, a fall from a height for 4, a crush injury for 3 and a sport‐related accident for 1. Twelve patients had comminuted fracture of the acetabular roof. Seven patients had associated cartilaginous damage of the femoral head. Other concomitant complications included shock in 3 patients, closed head injury in 4, extremity, spine, or visceral injury in 18 and incomplete sciatic nerve injury in 2.

All patients were evaluated by one anteroposterior and two oblique radiograms, as well as by computed tomography (CT). The radiographic diagnostic criteria for transtectal transverse fracture included: i) interruption by the fracture of the ilioischial line, the iliopectineal line and both lips of the acetabulum; ii) medial displacement of the lower fragment, with maintenance of the relationship between the inferior part of the ilioischial and teardrop; iii) in addition, intersection of the roof in its inner part, and an intact obturator foramen; iv) in axial CT scans, a sagittal fracture line at the level of the acetabular roof, and an intact quadrilateral surface; v) some cases showed multiple fracture fragments in the roof area.

The indications for surgery were displacement greater than 3 mm, non‐concentric reduction after dislocation of the hip, any intra‐articular fracture, displaced fracture involving the weight‐bearing dome (conforming to Matta's guidelines for measurement of roof arcs), and the absence of osteoporosis.

Surgical technique

Preoperatively, skeletal traction was used to prevent additional damage to the cartilage of the femoral head. The average interval from injury to operation was 9.1 days (range, 4–21 days). Because greater displacement of the transtectal transverse fractures was most commonly at the level of the posterior column, the Kocher‐Langenbeck approach was often chosen 2 . On the other hand, in the very small number of cases where displacement of the transverse fracture was obviously at the level of the anterior column, or the fracture line ran obliquely in a cephalic direction, the choice of an ilioinguinal approach was considered reasonable. Where the transtectal transverse fracture was associated with comminuted fracture of the weight bearing dome, or reduction of the fracture could not be achieved by a simple approach, a combined approach (ilioinguinal and Kocher‐Langenbeck) was applied. Once sufficient exposure of the fracture had been achieved, a 4 or 6 mm AO lag screw was inserted on either side of the fracture line. Reduction forceps were used for gripping the screw heads to put traction on the fragments. Then an attempt was made to remove scar tissue and release the fragments. After that, reduction was performed with reduction forceps. Generally, the distal fragment of the transtectal transverse fracture was displaced in the posterior‐medial direction, and rarely in rotation. Therefore, reduction forceps were applied to assist lateral and distal traction of the distal fragment. Once reduction had been achieved, bone‐reduction forceps were used to provide temporary fixation. Final fixation was then buttressed by the application of a reconstructive plate, appropriately contoured to accommodate the shape of the column. If small intra‐articular fragments were found, arthrotomy and removal of bone fragments was performed. Seven patients were identified as having damage to the cartilage of the femoral head during surgery.

Postoperative antibiotic therapy was used routinely, and closed negative pressure drainage was used for one to two days. Generally, patients began passive range‐of‐motion exercises and static muscle contraction on the third or fourth postoperative day. Gradually, active‐range‐of‐motion exercises of the hip were encouraged and progressive partial weight‐bearing with use of crutches was maintained for 6–8 weeks. Full weight bearing was allowed only after radiographic union had been confirmed.

Clinical and radiological outcome

Postoperative plain radiographs were reviewed to assess fracture reduction according to Matta's criteria. At each follow‐up, the clinical outcome was evaluated using a modified Merle d'Aubigné and Postel grading system 4 . Radiographic evaluation was based on the criteria described by Matta 4 . Fracture and radiographic variables were also analyzed in an attempt to identify possible associations with clinical outcome. These variables included quality of reduction, presence of comminuted fracture of the weight‐bearing dome, subtle hip instability, and damage to the cartilage of the femoral head. Heterotopic ossification was graded according to the classification system of Brooker et al. 9 .

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). χ2 tests were used to identify predictive variables associated with excellent and good clinical outcomes. We considered a P‐value of 0.05 to be statistically significant. The relationship between the clinical outcome and final radiographic grade was evaluated by Kendall's tau‐b rank correlation. A P‐value of <0.01 was accepted as indicating good agreement between two groups. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to determine which variables were most related to clinical outcome, and a P‐value of <0.05 was considered to indicate a significant result.

Results

The degree of fracture reduction as measured on three standard plain radiographs was graded as anatomic in 31 patients, imperfect in 4 and unsatisfactory in 2. Two hips were diagnosed as having subtle instability by radiography. According to the modified Merle d'Aubigné and Postel grading system, the clinical outcome was graded as excellent in 16 patients, good in 14, fair in 4 and poor in 3. At final follow‐up, the radiographic result was graded as excellent in 14 patients, good in 15, fair in 4 and poor in 4. There was a significant correlation between the final clinical and radiographic outcomes (t= 0.915, P < 0.01, Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and radiological outcomes (%)

| Grade | Clinical grade | Radiographic grade |

|---|---|---|

| Excellent | 16 (43.24%) | 14 (37.84%) |

| Good | 14 (37.84%) | 15 (40.54%) |

| Fair | 4 (10.81%) | 4 (10.81%) |

| Poor | 3 (8.11%) | 4 (10.81%) |

Variables identified as factors associated with achievement of excellent to good results were analyzed between various pairs of groups. Excellent and good rates in the anatomic and non‐anatomic reduction groups were 90.32% and 33.33%, respectively (χ2= 10.643, P= 0.007). Excellent and good rates in the simple dome fracture and comminuted dome fracture groups were 92.00% and 58.33%, respectively (χ2= 5.991, P= 0.025). Excellent and good rates in the hip instability and stability groups were 0 and 85.71%, respectively (χ2= 9.061, P= 0.032). Excellent and good rates in the femoral head damage and non‐femoral head damage groups were 42.86% and 90.00%, respectively (χ2= 8.223, P= 0.015). All four variables had a significant influence on excellent and good rates in functional outcome (Table 2). Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed the two variables that were most related to a fair to poor result were unsatisfactory fracture reduction (P= 0.001) and damage to the cartilage of the femoral head (P= 0.023).

Table 2.

Risk factors and clinical outcome (%)

| Grade | Excellent | Good | Fair | Poor | Excellent and good rates | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of fracture reduction | ||||||

| Anatomic reduction | 15 (48.39%) | 13 (41.94%) | 2 (6.45%) | 1 (4.22%) | 90.32% | 0.007 |

| Non‐anatomic reduction | 1 (16.67%) | 1 (16.67%) | 2 (33.33%) | 2 (33.33%) | 33.33% | |

| Weight‐bearing dome fracture | ||||||

| Simple dome fracture | 14 (56.00%) | 9 (36.00%) | 1 (4.00%) | 1 (4.00%) | 92.00% | 0.025 |

| Comminuted dome fracture ) | 2 (16.67% | 5 (41.66%) | 3 (25.00%) | 2 (16.67%) | 58.33% | |

| Instability of the hip | ||||||

| Yes | 2 (100%) | 0% | 0.032 | |||

| No | 16 (45.71%) | 14 (40.00%) | 4 (11.43%) | 1 (2.86%) | 85.71% | |

| Damage to the cartilage of the femoral head | ||||||

| Yes | 3 (42.86%) | 2 (28.57%) | 2 (28.57%) | 42.86% | 0.015 | |

| No | 16 (55.17%) | 11 (37.93%) | 2 (3.45%) | 1 (3.45%) | 90.00% |

Discussion

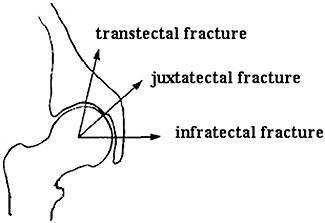

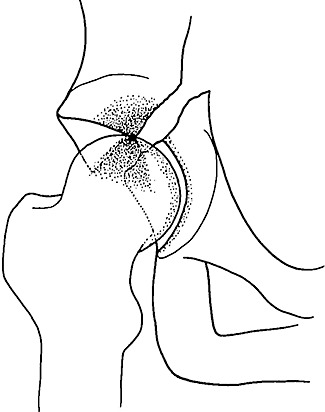

According to the different fracture locations on radiograph, Letournel classified transverse fracture into three types, namely transtectal, juxtatectal, and infratectal fracture 1 (Fig. 1). In transtectal transverse fracture, the roof is intersected by the fracture line and an unfractured external segment of the roof attached to the iliac wing fragment remains(Fig. 2). Letournel and Judet found the incidence of transtectal transverse fracture to be low, accounting for approximately 1.38% of all acetabular fractures. They considered that transverse acetabular fracture had a simple appearance on plain radiograph and was easy to treat; 87% of the patients in their study had satisfactory results 2 . However, in our series of 471 acetabular fractures, 8.94% (40/471) were transtectal transverse fractures. The excellent and good rates in clinical and radiographic outcome were 81.08% and 78.38%, respectively. These findings are not consistent with those of Letournel and Judet 2 . Acknowledging these differences, we have identified unsatisfactory fracture reduction, comminuted fracture of the weight bearing dome, subtle hip instability and damage to the cartilage of the femoral head as negative prognostic factors with regard to outcome in these patients.

Figure 1.

Different types of transverse fracture of the acetabulum.

Figure 2.

Transtectal transverse acetabular fracture.

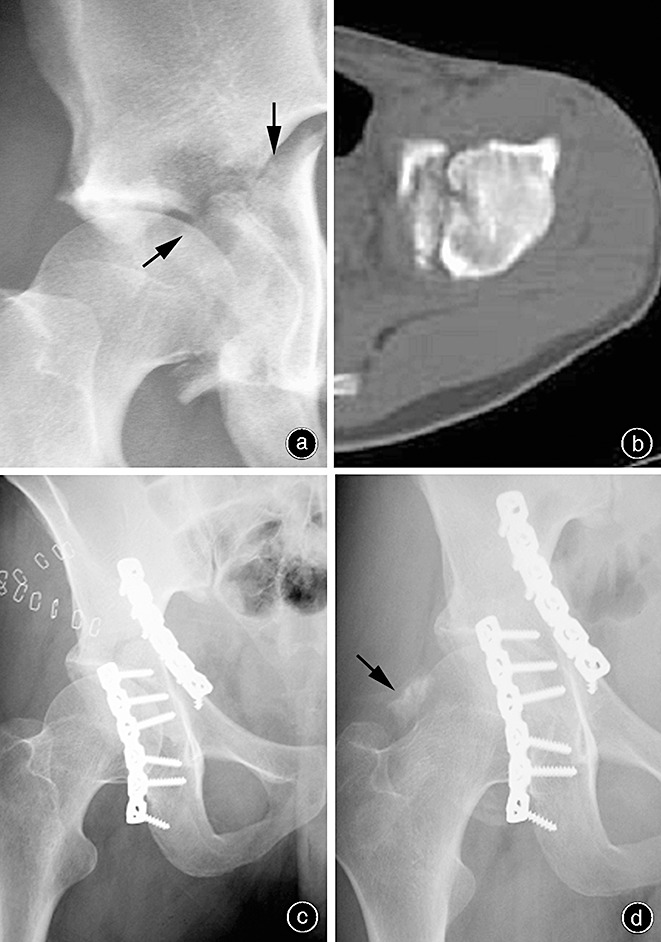

Acetabular fracture is a common type of articular fracture. Current treatments of fractures where the articular surface is involved are anatomic reduction, stable fixation and early mobilization of the joint. Logically, this is also standard procedure for most displaced acetabular fractures. Several studies state that the clinical results of acetabular fractures treated surgically are significantly correlated with the quality of reduction 1 , 2 . Residual gap or step‐off deformity increases peak contact pressure, which increases the risk of post‐traumatic arthritis. Hak et al. have reported that transtectal transverse fractures with 2–4 mm of displacement increase peak pressure loading arising from normal maximum contact pressure across the weight‐bearing part of the hip joint from 9.55 ± 2.62 megapascals (MPa) to 21.30 ± 11.75 MPa 10 . This marked change in the pressure applied to the articular cartilage of the hip joint results in breakdown of that cartilage. Malkani et al. confirmed the previous finding in a biomechanical study using a transtectal acetabular fracture model 11 . They found that transtectal acetabular fracture with greater than 1 mm of step‐off displacement could lead to a significant increase in peak pressure on the articular surface. In the current study, we have shown 90.32% excellent and good results in the anatomic reduction group, whereas the non‐anatomic reduction group had 33.33% excellent and good results. This indicates that the clinical outcome is directly related to the accuracy of reduction (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

A 42‐year‐old woman was involved in a traffic accident in which she sustained a transtectal transverse fracture of the acetabulum. (a) Immediate anteroposterior radiograph. The arrow indicates a typical fracture disrupting the ilioischial and iliopectal lines and both lips of the acetabulum. (b) Representative section from the CT scan showing a fracture line located on the weight‐bearing dome of the acetabulum. (c) Postoperative anteroposterior radiograph. The reduction was graded as anatomical. (d) Anteroposterior radiograph obtained at the 26th month of follow‐up showing a normal appearing hip with type I heterotopic ossification (arrow).

Depending on whether or not there is comminuted fracture of the acetabular dome, Oh et al. have classified transtectal transverse fracture into two major categories: simple and comminuted transtectal transverse fracture 6 . These authors noted that the rate of anatomical reduction was less in comminuted transtectal transverse fracture than in simple fracture, and comminution of transtectal transverse fracture had a significant correlation with a poor clinical outcome. In our series, we found that a satisfactory clinical outcome was obtained in the simple dome fracture group which had 92.00% excellent and good results. On the contrary, only 58.33% of cases in the comminuted dome fracture group obtained excellent and good outcomes. These findings signify that comminuted dome fracture might have an adverse influence on the clinical outcome. In addition to unsatisfactory reduction, Murray et al. have reported that comminuted fracture can accelerate apoptosis of the articular cartilage, and eventually lead to post‐traumatic arthritis 12 .

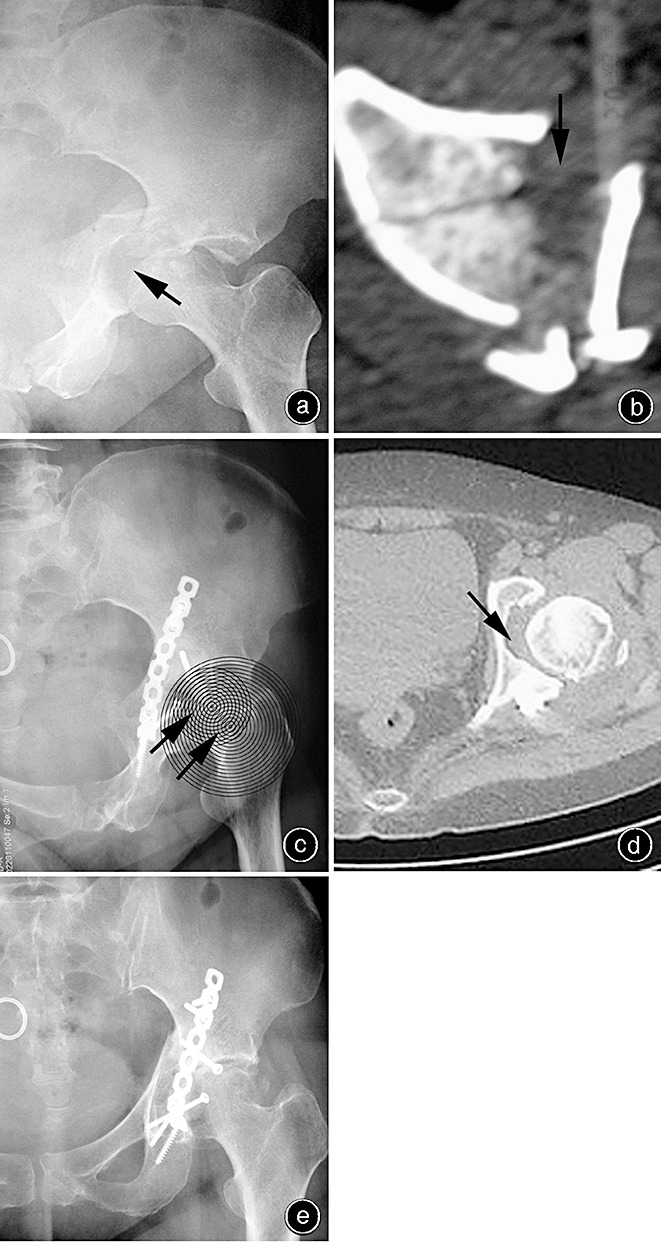

Matta and Merritt found that hip joint congruity is closely correlated with hip stability 13 . Displaced acetabular fractures involving the weight‐bearing dome indicates loss of parallelism between the femoral head and acetabular roof, which reflects an unstable, nonconcentric articulation and will lead to post‐traumatic arthritis. Hence, they described the categories of roof arc angle that can be used to assess weight‐bearing dome and hip stability following fracture 13 . Thomas et al. evaluated the hip stability of 22 transtectal acetabular fracture models, and confirmed that fractures with a roof arc angle >60° had sufficient residual weight‐bearing dome to sustain hip stability 14 . These authors considered that in these cases it was not necessary to achieve anatomic reduction and non‐operative management could be effectively utilized. However, some investigators have pointed out that the amount of residual weight‐bearing dome is not the only determinant of hip stability. In some patients, joint stability is not maintained even if satisfactory reduction and stable fixation are achieved. Tornetta found that, of 41 acetabular fractures which met the criteria for non‐operative management, three unstable hips were identified in dynamic fluoroscopic stress views 15 . He concluded that dynamic stress views can identify subtle instability in patients who would normally be considered for non‐operative treatment. In addition, Saterbak et al. noted that subtle subluxation was observable on radiographs of five acetabular fractures in the posterior column in which non‐anatomic reduction was achieved 16 . Although the etiology of the subluxation was not reported in this study, the authors found that subluxation may result in femoral head wear due to abnormal stress on the acetabular fossa during movement, which eventually causes mechanical destruction of the femoral head, leading to post‐traumatic arthritis 16 . McKinley et al. 17 demonstrated that subtle instability can be a potent determinant of post‐traumatic arthritis 17 . However, little is known of the local mechanical effects of global instability in the acetabulum. In the present study, two hips were diagnosed as having subtle instability by postoperative radiography. This subtle instability is characterized by the acetabulum and femoral head having different geometrical centres, combined with an expanded acetabular fossa. We found that subtle instability of the hip can be correlated with unsatisfactory reduction in some planes, as well as with development of post‐traumatic arthritis (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

A 36‐year‐old woman was involved in a traffic accident in which she sustained a transtectal transverse fracture of the acetabulum with central dislocation of the hip. (a, b) Immediate anteroposterior radiograph and CT scan. (c) Postoperative anteroposterior radiograph (the concentric circles and arrows demonstrate that the acetabulum and femoral head have different geometrical centres). (d) Postoperative CT scan showing non‐anatomic fracture reduction with subtle instability of the hip (arrow) (e) After a follow‐up of 17 months, the patient showed a poor result with evidence of arthritic change.

Martin et al. found that, despite achieving anatomical reduction of intra‐articular fracture, some cases still had a poor clinical outcome 18 . These authors attributed this finding to direct damage to the cartilage of the femoral head, which can severely exacerbate necrosis and apoptosis of the articular cartilage, and eventually lead to post‐traumatic arthritis. In a long‐term study, Letournel and Judet noted that femoral head damage is particularly likely in transtectal transverse fractures 2 . Mears et al. noted that damage to the cartilage of the femoral head is an important determinant of prognosis 7 . Cartilage damage occurred not only at the point of trauma, but was commonly also found in the absence of skeletal traction after acetabular fracture. Oransky and Sanguinetti found that damage to the articular cartilage in the weight‐bearing zone poorly influenced the outcome of patients with acetabular fracture 19 . More importantly they noted that, compared with avascular necrosis of the femoral head, damaged cartilage of the femoral head is probably more significant in predicting the clinical outcome. In the current study, three of seven patients (42.86%) with associated damage to the cartilage of the femoral head achieved an excellent to good clinical outcome. Conversely, better results were observed where there was no damage to the cartilage of femoral head group with 90.00% excellent and good outcomes. These findings indicate that damage to the cartilage of the femoral head compromises the outcome of transtectal transverse fracture. To avoid further abrasion of the femoral head against fracture fragments, preoperative skeletal traction is a crucial ingredient in the treatment of patients with transtectal transverse fracture. Simultaneously, where damage to the cartilage of the femoral head has been observed during surgery, we suggest postponing weight‐bearing postoperatively.

Marsh et al. have shown that unsatisfactory fracture reduction, joint instability, and articular cartilage damage are the three most important risk factors for the prognosis of articular fracture 20 . Similarly, unsatisfactory fracture reduction, comminuted fracture of the weight bearing dome, subtle postoperative hip instability and damage to the cartilage of the femoral head correlate with poor outcomes in transtectal transverse fracture. Multiple logistic regression analysis of the four risk factors revealed that unsatisfactory fracture reduction and damage to the cartilage of the femoral head are the factors most strongly associated with poor outcome. Therefore, with a dedicated team, avoiding the above‐mentioned negative prognostic factors could result in a satisfactory clinical outcome.

Disclosure

This manuscript does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s). No funds were received in support of this work. No benefits of any type have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1. Letournel E. Acetabulum fractures: classification and management. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1980, 151: 81–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Letournel E, Judet R. Fractures of the Acetabulum, 2nd edn. New York: Springer Verlag, 1993; 33–66. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matta JM, Mehne DK, Roffi R. Fractures of the acetabulum. Early results of a prospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1986, 205: 241–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Matta JM, Anderson LM, Epstein HC, et al. Fractures of the acetabulum: a prospective analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1986, 205: 230–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Sun JY, Tang TS, Hong TL, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of displaced transverse fractures of the acetabulum(Chin). Zhonghua Gu Ke Za Zhi, 1996, 16: 540–543. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oh CW, Kim PT, Park BC, et al. Results after operative treatment of transverse acetabular fractures. J Orthop Sci, 2006, 11: 478–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mears DC, Velyvis JH, Chang CP. Displaced acetabular fractures managed operatively: indicators of outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2003, 407: 173–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mohanty K, Taha W, Powell JN. Non‐union of acetabular fractures. Injury, 2004, 35: 787–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brooker AF, Bowerman JW, Robinson RA, et al. Ectopic ossification following total hip replacement. Incidence and a method of classification. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1973, 55: 1629–1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hak DJ, Hamel AJ, Bay BK, et al. Consequences of transverse acetabular fracture malreduction on load transmission across the hip joint. J Orthop Trauma, 1998, 12: 90–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Malkani AL, Voor MJ, Rennirt G, et al. Increased peak contact stress after incongruent reduction of transverse acetabular fractures: a cadaveric model. J Trauma, 2001, 51: 704–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murray MM, Zurakowski D, Vrahas MS. The death of articular chondrocytes after intra‐articular fracture in humans. J Trauma, 2004, 56: 128–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Matta JM, Merritt PO. Displaced acetabular fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1988, 230: 83–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thomas KA, Vrahas MS, Noble JW Jr, et al. Evaluation of hip stability after simulated transverse acetabular fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1997, 340: 244–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tornetta P 3rd. Non‐operative management of acetabular fractures. The use of dynamic stress views. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1999, 81: 67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saterbak AM, Marsh JL, Nepola JV, et al. Clinical failure after posterior wall acetabular fractures: the influence of initial fracture patterns. J Orthop Trauma, 2000, 14: 230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McKinley TO, Rudert MJ, Koos DC, et al. Incongruity versus instability in the etiology of posttraumatic arthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2004, 423: 44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Martin J, Marsh JL, Nepola JV, et al. Radiographic fracture assessments: which ones can we reliably make? J Orthop Trauma, 2000, 14: 379–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oransky M, Sanguinetti C. Surgical treatment of displaced acetabular fractures: results of 50 consecutive cases. J Orthop Trauma, 1993, 7: 28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Marsh JL, Buckwalter J, Gelberman R, et al. Articular fractures: does an anatomic reduction really change the result? J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2002, 84: 1259–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]