Abstract

Objective: To investigate whether single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) of the calmodulin1 (CALM1) and estrogen receptor‐α genes correlate with double curve in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS).

Methods: A total of 67 Chinese patients with AIS with double curve and 100 healthy controls were recruited. Curve pattern and Cobb angle of each patient were recorded. The Cobb angle is at least 30°. There were 60 patients with Cobb angle ≥ 40°. According to the apical location of the major curve, there were 40 thoracic curve patients. Four polymorphic loci, including rs12885713 (−16C > T) and rs5871 in the CALM1 gene and rs2234693 (Pvu II) and rs9340799 (Xba I) in the estrogen receptor 1 (ER1) gene were analyzed by the ABI3730 genetic analyzer.

Results: The current study indicates that: (i) there are statistical differences between patients with double curve, with Cobb angle ≥ 40° and with thoracic curve and healthy controls in the polymorphic distribution of the rs2234693 site of the ER1 gene, (P= 0.014, 0.0128, 0.0184 respectively); (ii) there is a difference between patients with double curve and controls in the polymorphic distribution of the rs12885713 site in the CALM1 gene (P= 0.034); and (iii) there is a difference between thoracic curve patients and controls in the polymorphic distribution of the rs5871 site in the CALM1 gene (P= 0.0102).

Conclusions: Different subtypes of AIS might be related to different SNP. A combination of CALM1 and ER1 gene polymorphisms might be related to double curve in patients with AIS. Further study is necessary to confirm these hypotheses.

Keywords: Scoliosis; Polymorphism, genetic; Calmodulin; Estrogen receptor alpha; Genes

Introduction

Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis (AIS) is defined as a structural lateral curvature of the spine for which no cause can be established. Many hypotheses concerning the etiopathogenesis of AIS have been proposed, including genetic predisposition, abnormal growth, hormonal disturbances and developmental neuromuscular dysfunction 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , but more and more studies have provided strong evidence that genetic factors play a role in this condition and that AIS likely represents a complex genetic trait under the influence of multiple predisposition genes 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 .

There are two main types of approach in genetic epidemiology: linkage and association analysis 11 . The former is used to locate chromosomal regions that potentially contain the gene of interest. The general principle of linkage analysis is to search within families for chromosomal regions which segregate non‐randomly with the phenotype of interest. The latter is used to investigate the role of polymorphisms of genes either by focusing on a few candidate regions or by using a genome‐wide search. Classical association studies are population‐based case‐control studies that compare the frequency of a given marker allele A between unrelated affected cases and unaffected controls.

Five recent studies using linkage analysis have reported possible relationships between marker loci and AIS. Wise et al. reported evidence for linkage on chromosomes 6p, distal 10q and 18q in a single extended family with idiopathic scoliosis in an affected‐only analysis 12 . Salehi et al. studied a single three‐generation Italian family with AIS and reported evidence of linkage to chromosome 17p11.2 13 . Chan et al. reported linkage to a 5.2 cm region on chromosome 19p13.3 in a group of seven Chinese families and noted a second candidate region on chromosome 2 14 . In an earlier analysis by Justice et al., evidence of linkage with markers on chromosome Xq23–26 in a subset of the families most likely to be X‐linked dominant was reported 15 . A genomic screen and statistical linkage analysis of 202 families with at least two individuals with idiopathic scoliosis was performed by Miller et al. 16 . They reported that candidate regions on chromosomes 6, 9, 16, and 17 might have the strongest evidence for linkage across all subsets considered.

On the other hand, genetic association analysis has recently been used to study the relationship between polymorphisms of estrogen receptor‐1 (ER 1) gene and AIS. Using a case‐only sample of 304 Japanese AIS patients, Inoue et al. reported an association between polymorphism at locus rs9340799 (Xba I) of the ER 1 gene and curve severity in AIS 17 . In another report, Wu et al.also suggested that Xba I site polymorphism may be a risk factor for AIS 18 . However in a case‐control study of 540 Chinese AIS girls with Cobb angle > 20°, the results of Tang et al. were not in agreement with this 19 .

Previous studies have often stratified patients according to Cobb angle > 20°, 30° or 40° 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 . However, in AIS patients, the risk of progression is primarily related to curve‐specific factors and growth potential. Weinstein have reported that AIS has a greater tendency to progress in patients with double as opposed to single curve, and that the larger the curve at detection, the greater the risk of progression 20 . Therefore, based on these previous reports, we thought that different SNP might be related to occurrence or progression of single, double or triple curve. The key to testing this hypothesis was to choose several appropriate SNP and study a large sample.

Calmodulin, a calcium‐binding receptor protein, is a critical mediator of eukaryotic cellular calcium function and a regulator of many important enzymatic systems 21 . Previous studies have shown that increased calmodulin concentrations in platelets are associated with progression of AIS, especially where there are double curve patterns 22 , 23 , 24 . On the other hand, Bouhoute and Leclercq have reported that calmodulin has an affinity for ER and is able to decrease the estrogen‐binding capacity of ER 25 , 26 , 27 . In addition, Mototani et al. have identified a functional SNP (T/C polymorphism, dbSNP#: rs12885713) in the promoter region of the CALM 1 gene which affects transcription of the gene 28 . Otherwise, rs5871 (T/C polymorphism), average heterozygosity 0.201 ± 0.245, in the 3′‐UTR of CALM1, has been reported to likely be related to the stability and transcription of mRNA 29 , 30 .

Based on the above‐mentioned research, the concentration of calmodulin might be a prognostic sign in regard to curve progression, and ER 1 or CALM1 gene polymorphism might be candidate gene for AIS. The present study further analyzes the association between AIS with double curve and polymorphisms of the CALM1 gene and ER 1 genes.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A total of 67 patients with AIS with double curve were recruited as cases and another group of 100 healthy adolescents as controls. The double curve diagnosis was according to Scoliosis Research Society (SRS) definition for curvature (i.e. the spine deviates from the midline with a Cobb angle of >10°, and the vertebra or disc furthest from the midline horizontally on a standing anteroposterior view is defined as the apex) 31 .

All patients underwent surgery at the Spinal Center of our hospital from October 2005 to April 2007. The cases, 7 of whom were male and 60 female, with an average age of 15.09 ± 2.37 years (range, 10–20), were diagnosed by clinical examination and roentgenograms, and confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to exclude the possibility of central nervous system disorders of cerebrum and spinal cord. The Cobb angle of the major curve of AIS ranged from 30° to 90°. There were 60 patients with Cobb angle ≥ 40°. According to the apical location, there were 40 thoracic curves (apex between T2 and the T11–12 disc), 12 thoracolumbar curves (apex between T12 and L1) and 15 lumbar curves (apex between L1–2 and L4–5 discs), respectively. The healthy controls, 25 of whom were male and 75 female, with an average age of 15.55 ± 2.21 years (range, 10–19), were recruited from a trauma ward. All controls were examined by an orthopedic surgeon with the forward bending test to rule out any scoliosis. In any case of uncertainty, the clinician referred the subject for a radiograph to ensure the absence of any scoliosis. Both patients and controls were excluded from the study if they had congenital deformities, neuromuscular or endocrine diseases, skeletal dysplasia, connective tissue abnormalities or mental retardation.

There was no significant difference in age (15.09 ± 2.37 vs. 15.55 ± 2.21 years) between patients with double curve and the control group (t=−1.282, P= 0.202). The gender distribution in two groups was compared using the χ2 test (χ2= 0.741, P= 0.390). Thus the subjects in the two groups were age‐ and gender‐ matched.

Informed consent was obtained from both parents and subjects. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the university.

Blood sampling

Blood samples were taken from each subject by venipuncture and DNA extracted with a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA).

Molecular methods

Table 1 shows the oligonucleotide primers that were used to determine the different SNP of the ER1 or CALM1 genes, respectively.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers determining different SNP

| SNP | The oligonucleotide primers | |

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| rs12885713(−16C > T) | 5′‐AAGATCAAGCTACACATCAG‐3′ | 5′‐TCGGAGCACACGAAGTACAAG‐3″ |

| rs5871 | 5′‐AGGGTTATGTGGCAATGACG‐3′ | 5′‐TCGGAGCACACGAAGTACAAG‐3″ |

| rs2234693(Pvu II) + rs9340799(Xba I) | 5′‐AGGGTTATGTGGCAATGACG‐3′ | 5′‐TCTGGGAGATGCAGCAGATC‐3′ |

The rs12885713 (−16C > T) allele which has an effect on transcription of the gene is located in the promoter region of the CALM 1 gene. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed in 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 63°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s, with a final extension for 10 min at 72°C.

The rs5871 allele which might be associated with stability and transcription of mRNA is located in the 3′‐UTR region of the CALM 1 gene. PCR was performed in 35 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, 61°C for 40 s and 72°C for 60 s, with a final extension for 5 min at 72°C.

The rs2234693 (Pvu II) and rs9340799 (Xba I) are located in intron 1, only 50 bp apart, 400‐bp upstream of exon 2 of the ER 1 gene. PCR was performed in 35 cycles of 94°C for 40 s, 59°C for 30 s and 72°C for 60 s, with a final extension for 5 min at 72°C.

DNA sequencing was performed on the products of PCR with the ABI3730 genetic analyzer (AME Bioscience, Norwalk, CT, USA) and sequencing results were read with the GeneTool Lite program. To ensure the sequencing results were accurate, we performed re‐sequence of the DNA in all samples from the opposite direction and confirmed the previous results.

Statistical analysis

The χ2 test was used to determine the significance of differences between patients and controls in the distribution of SNP, and to test whether the genotype frequencies deviated from the Hardy‐Weinberg equilibrium (HWE). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Genotypes of the CALM1 and ER1 genes

The genotypes in the present study are shown in 1, 2, 3, 4. All 12 genotypes were detected in the present study. None of the gene polymorphic distributions deviated significantly from the HWE in the case groups (Table 2). Because the rs9340799 (Xba I) allele polymorphic distributions deviated significantly from the HWE in the healthy controls, we didn't investigate the function of the site in our further analysis.

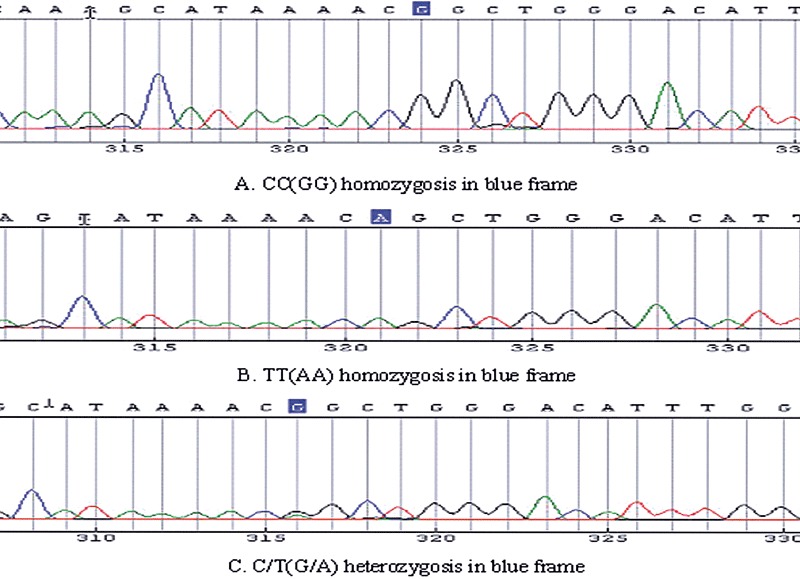

Figure 1.

rs12885713 (−16C > T) allele polymorphisms consisting of CC and TT homozygosis, C/T heterozygosis.

Figure 2.

rs5871 allele polymorphisms consisting of CC and TT homozygosis, C/T heterozygosis.

Figure 3.

rs2234693 Pvu II allele polymorphisms consisting of CC and TT homozygosis, C/T heterozygosis.

Figure 4.

rs9340799 Xba I allele polymorphisms consisting of AA and GG homozygosis, A/G heterozygosis.

Table 2.

HWE analysis of the four SNP

| Analysis factors | AIS | Controls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 value | P value | χ2 value | P value | |

| rs12885713 | 0.096 | >0.05 | 0.077 | >0.05 |

| rs5871 | 0.134 | >0.05 | 1.780 | >0.05 |

| rs2234693 | 1.319 | >0.05 | 0.02 | >0.05 |

| rs9340799 | 0.819 | >0.05 | 6.38 | 0.01 |

HWE, Hardy‐Weinberg Equilibrium.

Association between SNP and double curve

Table 3 demonstrates the association between double curve and polymorphic distribution of the CALM1 and ER1 genes. Significant differences were shown between cases and controls in polymorphic distribution of either the rs12885713 (−16C > T) site in the CALM1 gene or the rs2234693 (Pvu II) site in the ER1 gene (P 0.034, 0.014, respectively). In addition, the frequency of the −16C allele in the cases (71.6%) was less than in the controls (81.5%).

Table 3.

Analysis of double curve and three different SPN

| Allele | Double curve † | Controls ‡ | χ2 value | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T | C | T | |||

| rs12885713 | 96 (71.6%) | 38 (28.4%) | 163 (81.5%) | 37 (18.5%) | 4.478 | 0.034 |

| rs5871 | 59 (44%) | 75 (56%) | 109 (54.5%) | 91 (45.5%) | 3.519 | 0.061 |

| rs2234693 | 41 (30.6%) | 93 (69.4%) | 88 (44%) | 112 (56%) | 6.081 | 0.014 |

67 double curve patients.

100 controls.

Association between SNP and Cobb angle

Among the 67 double curve patients, there were 60 patients with Cobb angle ≥ 40°. Table 4 indicates the association between Cobb angle and polymorphic distribution of the CALM 1 or ER 1 gene. A significant difference was shown between cases (Cobb angle ≥ 40°) and controls in the polymorphic distribution of the rs2234693 (Pvu II) site in the ER 1 gene (P 0.0128). In addition, the frequency of the −16C allele in the cases (73.3%) was less than in the controls (81.5%).

Table 4.

Analysis of Cobb angle and three different SPN

| Allele | AIS | Controls | χ2 value | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T | C | T | |||

| rs12885713 | 88 (73.3%) | 32 (26.4%) | 163 (81.5%) | 37 (18.5%) | 2.9575 | 0.0855 |

| rs5871 | 54 (45%) | 66 (55%) | 109 (54.5%) | 91 (45.5%) | 2.7085 | 0.0998 |

| rs2234693 | 36 (30%) | 84 (70%) | 88 (44%) | 112 (56%) | 6.1935 | 0.0128 |

Cobb angle ≥ 40°, 60 patients.

Association between SNP and apical location of major curve

According to the apical location, there were 40 thoracic curves (apex between T2 and the T11–12 disc). Table 5 illustrates the association between thoracic curve patients and polymorphic distribution of the CALM 1 or ER 1 gene. Significant differences were shown between thoracic curve patients and controls in the distribution of the rs5871 and rs2234693 allele polymorphisms (P= 0.0102, 0.0184, respectively). In addition, the frequency of the −16C allele in the cases (75%) was less than in the controls (81.5%).

Table 5.

Analysis of thoracic curve † and three different SPN

| Allele | AIS | Controls | χ2 value | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T | C | T | |||

| rs12885713 | 60 (75%) | 20 (25%) | 163 (81.5%) | 37 (18.5%) | 1.4891 | 0.2224 |

| rs5871 | 30 (37.5%) | 50 (62.5%) | 109 (54.5%) | 91 (45.5%) | 6.6061 | 0.0102 |

| rs2234693 | 23 (28.75%) | 57 (71.25%) | 88 (44%) | 112 (56%) | 5.5540 | 0.0184 |

Apex between T2 and the T11–12 disc, 40 patients.

Discussion

Estrogen receptors, calmodulin and their interaction

Estrogen receptors

As a critical mediator of cellular proliferation and differentiation in tissues such as endometrium, mammary gland, bone, cardiovascular system, brain and urogenital tract, estrogen exerts its function through receptor binding. The ER gene has been shown to be expressed in both human osteoblasts and osteoclasts, and mutations of the ER1 gene were recently shown to reduce bone density and delay skeletal growth in affected humans 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 .

On the assumption that the estrogen reaction to skeletal and sexual growth is genetically determined by ER gene polymorphism, Inoue et al. thought that ER1 gene polymorphism might be related to curve progression in idiopathic scoliosis 17 . However, when different samples and analysis methods were used, such as case‐only sample study to case‐control study, with special attention being paid to the Hardy‐Weinberg equilibrium in the latter studies, this hypothesis was not confirmed by other studies 17 , 18 , 19 .

Calmodulin

As a calcium‐binding receptor protein, calmodulin is a critical mediator of eukaryotic cellular calcium function and a regulator of many important enzymatic systems 21 . It has often been thought that calmodulin can affect the contractile systems of both skeletal muscle and platelets because actin and myosin resemble each other 21 , 41 . Calmodulin regulates the contractile properties of muscles and platelets through its interaction with actin and myosin and regulates cellular calcium through transport across the cell membrane.

Previous studies have shown that increased calmodulin concentrations in platelets might be associated with progression of AIS. Cohen et al. reported a 2.5–3 fold increase in the concentration of calmodulin in platelets of patients who had AIS 22 . They also found that the concentration of calmodulin was associated with the severity of the spinal curve. Kindsfater et al. compared 17 patients who had AIS with varying degrees of curve with 10 age‐ and gender‐matched controls 23 . Their results showed that platelet calmodulin concentrations in skeletally immature patients with progressive curves (>10° progression per year) were considerably greater than the concentrations in patients with stable curves (3.8 vs. 0.7 nm/µm of protein). These data were based on a single calmodulin determination for each patient during the growth period. Conversely, calmodulin concentrations in the stable (non‐progressive) and control groups were very similar. In 2002, Lowe et al. reported the results in 55 patients with AIS who were followed up for 1–3 years during their growth period 24 . They found that calmodulin concentrations increased in all patients with progressive curves (13/13), remained stable in 73% of the patients with non‐progressive curves (11/15), and were higher generally in curves >30° and double curves. Calmodulin concentrations usually decreased in patients undergoing brace treatment (14/17) or spinal fusion (9/10).

The interaction of calmodulin and estrogen receptors

Bouhoute and Leclercq have reported that calmodulin has an affinity for estrogen receptors and can decrease the estrogen‐binding capacity of ER 25 , 26 , 27 . The dissociation constant of the estrogen‐binding receptor increased 2–3 fold when calmodulin was bound to ER. So, there is a possibility that the effect of calmodulin on curve progression is based on the loss of estrogen‐binding capacity of ER and that estrogen metabolism is a candidate for curve progression 17 .

On the basis of all the above‐mentioned studies, it is logical to clarify the association of CALM 1 and ER 1 gene polymorphisms with AIS with double curve.

Appropriate SNP in the CALM 1 gene

Previous studies have reported that there are two polymorphic loci located in the important regulation areas of the CALM 1 gene, rs12885713 (−16C > T) and rs5871, suggesting that mutations in these sequences might affect the expression of calmodulin 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 28 , 29 , 30 .

To investigate possible allelic differences in promoter activity generated by rs12885713 allele polymorphisms in vitro, Mototani et al. generated fusion constructs containing the –16C or –16T allele and transfected them in parallel into OUMS‐27 cells or Huh‐7 cells 28 . In OUMS‐27 cells, the construct containing the −16C allele showed a > 2‐fold greater luciferase activity than that containing the −16T allele. Similar results were observed in Huh‐7 cells. In addition, in order to investigate the effects of −16C > T on CALM1 transcription in vivo, they measured the amount of CALM1 transcripts under the control of each allele using RNA difference plot analysis 30 . The results suggested that the suppressor(s) of CALM1 transcription bind more tightly to the −16T allele. They concluded that the −16C allele increases CALM1 transcription both in vitro and in vivo.

The rs5871 site of the CALM 1 gene, heterozygosis 20.1%, is located in the region of 3′‐UTR. Previous reports have demonstrated that the 3′‐UTR region of mRNA is an important regulatory site controlling mRNA degradation machinery. 3′‐UTR RNA‐binding proteins which recognize specific elements of the mRNA sequence and secondary structure dictate the fate of mRNA transcripts. SNP in the 3′‐UTR could disrupt RNA‐protein interactions, resulting in alteration of mRNA stability 31 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 .

Association between these four SNP and double curves

Association between ER 1 gene polymorphism and double curves

The present study found significant differences between double curve patients and controls in the polymorphic distribution of rs2234693 (Pvu II) in the ER1 gene. In addition, considering current opinions concerning the apical location and severity of curvature, we stratified the cases according to apical location and Cobb angle ≥ 40°, respectively. The results again demonstrated an association between rs2234693 (Pvu II) allele polymorphism and double curves.

The different results of previous reports might be explained by the next two points. Firstly, the previous studies often took AIS as subjects and stratified the cases according to the severity of the curve while other curve‐specific factors, namely whether there were single, double or triple curves, were neglected. Unfortunately, in addition to the severity of the curve, double curve is another risk factor for curve progression. Secondly, as AIS is a multi‐factor disease, growth potential might have an effect on the final severity of the curve 20 . So, it seemed not enough to stratify the cases merely according to the severity of the curve in genetic studies.

Association between CALM 1 gene polymorphism and double curves

In the present study, a statistically significant difference has been shown between double curve patients and controls in polymorphic distribution of the rs12885713 allele. In addition, there is a statistical difference between thoracic curve patients and controls in polymorphic distribution of the rs5871 allele. However, these results were not replicated in further analysis with different grouping criteria.

In the present study the frequency of the −16C allele (rs12885713) in the cases was less than in the controls. Lowe and Mototani have reported that calmodulin concentrations are generally greater in cases with Cobb angle > 30° and double curve, and that the −16C allele could increase CALM1 transcription 24 , 28 . The present results seem contrary to these findings.

Considering previous reports that show calmodulin to have a high affinity for ER and ability to decrease the estrogen‐binding capacity of ER, we think that rs2234693 allele polymorphisms in ER1 gene might affect the occurrence of double curve. It is necessary to clarify the association between AIS and polymorphisms of the ER1 gene and CALM1 genes by further studies.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 30672137). This manuscript does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s). No benefits in any form have been or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1. Barrack RL, Whitecloud TS 3rd, Burke SW, et al. Proprioception in idiopathic scoliosis. Spine, 1984, 9: 681–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dickson RA. The aetiology of spinal deformities. Lancet, 1988, 1: 1151–1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miller NH. Genetics of familial idiopathic scoliosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2002, 401: 60–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burwell RG. Aetiology of idiopathic scoliosis: current concepts. Pediatr Rehabil, 2003, 6: 137–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lowe TG, Edgar M, Margulies JY, et al. Etiology of idiopathic scoliosis: current trends in research. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2000, 82: 1157–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelly PJ, Eisman JA, Sambrook PN. Interaction of genetic and environmental influences on peak bone density. Osteoporos Int, 1990, 1: 56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cowell HR, Hall JN, MacEwen GD. Genetic aspects of idiopathic scoliosis. A Nicholas Andry Award essay, 1970. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1972, 86: 121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wynne‐Davies R. Familial (idiopathic) scoliosis. A family survey. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1968, 50: 24–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Czeizel A, Bellyei A, Barta O, et al. Genetics of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Med Genet, 1978, 15: 424–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Riseborough EJ, Wynne‐Davies R. A genetic survey of idiopathic scoliosis in Boston, Massachusetts. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1973, 55: 974–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Neiderhiser JM. Understanding the roles of genome and envirome: methods in genetic epidemioloogy. Br J Psychiatry Suppl, 2001, 40: S12–S17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wise CA, Barnes R, Gillum J, et al. Localization of susceptibility to familial idiopathic scoliosis. Spine, 2000, 25: 2372–2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salehi LB, Mangino M, De Serio S, et al. Assignment of a locus for autosomal dominant idiopathic scoliosis (IS) to human chromosome 17p11. Hum Genet, 2002, 111: 401–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan V, Fong GC, Luk KD, et al. A genetic locus for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis linked to chromosome 19p13.3. Am J Hum Genet, 2002, 71: 401–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Justice CM, Miller NH, Marosy B, et al. Familial idiopathic scoliosis: evidence of an X‐linked susceptibility locus. Spine, 2003, 28: 589–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Miller NH, Justice CM, Marosy B, et al. Identification of candidate regions for familial idiopathic scoliosis. Spine, 2005, 30: 1181–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Inoue M, Minami S, Nakata Y, et al. Association between estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms and curve severity of idiopathic scoliosis. Spine, 2002, 27: 2357–2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wu J, Qiu Y, Zhang L, et al. Association of estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms with susceptibility to adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine, 2006, 31: 1131–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tang NL, Yeung HY, Lee KM, et al. A relook into the association of the estrogen receptor [alpha] gene (PvuII, XbaI) and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a study of 540 Chinese cases. Spine, 2006, 31: 2463–2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weinstein SL. Natural history. Spine, 1999, 24: 2592–2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheung WY. Calmodulin plays a pivotal role in cellular regulation. Science, 1980, 207: 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cohen DS, Solomons CS, Lowe TG. Altered platelet calmodulin activity in idiopathic scoliosis. Orthop Trans, 1985, 9: 106. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kindsfater K, Lowe T, Lawellin D, et al. Levels of platelet calmodulin for the prediction of progression and severity of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1994, 76: 1186–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lowe T, Lawellin D, Smith D, et al. Platelet calmodulin levels in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: do the levels correlate with curve progression and severity? Spine, 2002, 27: 768–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bouhoute A, Leclercq G. Antagonistic effect of triphenylethylenic antiestrogens on the association of estrogen receptor to calmodulin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1992, 184: 1432–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bouhoute A, Leclercq G. Modulation of estradiol and DNA binding to estrogen receptor upon association with calmodulin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1995, 208: 748–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bouhoute A, Leclercq G. Calmodulin decreases the estrogen binding capacity of the estrogen receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 1996, 227: 651–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mototani H, Mabuchi A, Saito S, et al. A functional single nucleotide polymorphism in the core promoter region of CALM1 is associated with hip osteoarthritis in Japanese. Hum Mol Genet, 2005, 14: 1009–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. UCSC Genome Bioinformatics . Cited 31 December 2006. Available from URL: http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi‐bin/hgc?hgsid=97296345&o=89941230&t=89941231&g=snp126&i=rs5871

- 30. Hollams EM, Giles KM, Thomson AM, et al. MRNA stability and the control of gene expression: implications for human disease. Neurochem Res, 2002, 27: 957–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kane WJ. Scoliosis prevalence: a call for a statement of terms. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1997, 126: 43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bashiardes S, Veile R, Allen M, et al. SNTG1, the gene encoding gamma1‐syntrophin: a candidate gene for idiopathic scoliosis. Hum Genet, 2004, 115: 81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morcuende JA, Minhas R, Dolan L, et al. Allelic variants of human melatonin 1A receptor in patients with familial adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Spine, 2003, 28: 2025–2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Inoue M, Minami S, Nakata Y, et al. Association between estrogen receptor gene polymorphisms and curve severity of idiopathic scoliosis. Spine, 2002, 27: 2357–2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nadeau JH. Modifier genes and protective alleles in humans and mice. Curr Opin Genet Dev, 2003, 13: 290–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kobayashi S, Inoue S, Hosoi T, et al. Association of bone mineral density with polymorphism of the estrogen receptor gene. J Bone Miner Res, 1996, 11: 306–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Matsubara Y, Murata M, Kawano K, et al. Genotype distribution of estrogen receptor polymorphisms in men and postmenopausal women from healthy and coronary populations and its relation to serum lipid levels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 1997, 17: 3006–3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yamada Y, Ando F, Niino N, et al. Association of polymorphisms of the estrogen receptor alpha gene with bone mineral density of the femoral neck in elderly Japanese women. J Mol Med, 2002, 80: 452–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wang Z, Yoshida S, Negoro K, et al. Polymorphisms in the estrogen receptor beta gene but not estrogen receptor alpha gene affect the risk of developing endometriosis in a Japanese population. Fertil Steril, 2004, 81: 1650–1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lohmueller KE, Pearce CL, Pike M, et al. Meta‐analysis of genetic association studies supports a contribution of common variants to susceptibility to common disease. Nat Genet, 2003, 33: 177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Agre P, Gardner K, Bennett V Association between human erythrocyte calmodulin and the cytoplasmic surface of human erythrocyte membranes. J Biol Chem, 1983, 258: 6258–6265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tourrière H, Chebli K, Tazi J. mRNA degradation machines in eukaryotic cells. Biochimie, 2002, 84: 821–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mangus DA, Evans MC, Jacobson A. Poly(A)‐binding proteins: multifunctional scaffolds for the post‐transcriptional control of gene expression. Genome Biol, 2003, 4: 223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wilkie GS, Dickson KS, Gray NK. Regulation of mRNA translation by 5′‐ and 3′‐UTR‐binding factors. Trends Biochem Sci, 2003, 28: 182–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Gow JM, Chinn LW, Kroetz DL. The effects of ABCB1 3′‐untranslated region variants on mRNA stability. Drug Metab Dispos, 2008, 36: 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]