Abstract

Objective

To retrospectively investigate the experience at one urban level one trauma center with gunshot femoral fractures with vascular injury and to examine the implication of surgical sequence with regards to short‐term complications and ischaemia time.

Methods

We performed a retrospective study of 24 patients treated at an urban level one trauma center over a 10‐year period with low velocity gunshot wounds resulting in femur fractures and major vascular injury. Data were stratified according to sequence of surgical intervention.

Results

The mean age was 31.3 years. Mean time to revascularization was highest in patients undergoing definitive orthopaedic fixation first (660 min) and lowest in patient undergoing shunting first (210 min). Most complications in patients undergoing vascular repair first, included two disrupted repairs requiring immediate revision after subsequent orthopaedic fixation. Other complications included compartment syndrome and one amputation.

Conclusion

Surgical sequence did not appear to impact the outcome with regard to limb loss, compartment syndrome, or mortality. Orthopaedic repair following vascular repair, however, is a risk for disruption of the vascular repair. We suggest that close and early direct communication between the orthopaedic and vascular surgeons take place in order to facilitate a satisfactory outcome.

Keywords: Blood vessels, Femoral fractures, Gunshot, Wounds

Introduction

Femoral fractures with combined vascular injury from low energy gunshot wounds are uncommon injury patterns not often seen in most trauma centers. When encountered, however, these require rapid, coordinated interdisciplinary care in order to achieve acceptable outcomes. Fortunately, outcomes are often better than those with blunt trauma and mangled extremities. Low velocity gunshot wound (GSW) femoral shaft fractures are successfully treated with intramedullary nailing without formal debridement of the wound or fracture1, 2, 3, 4, 5. However, vascular injuries require emergent revascularization and therefore take precedence over definitive fracture stabilization1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17. This creates a shift in priorities with multiple methods available to achieve rapid revascularization with skeletal stability. The current controversy centers on the proper sequence of surgical intervention with regards to orthopaedic and vascular stabilization.

The three commonly described approaches to the management of these injuries include (i) definitive vascular repair followed by definitive orthopaedic fixation; (ii) vascular shunt followed by definitive orthopaedic fixation followed by definitive vascular repair; and (iii) orthopaedic fixation followed by vascular repair. Temporary orthopaedic stabilization in the form of an external fixator followed by definitive vascular repair followed by delayed definitive orthopaedic fixation is also a described treatment option.

While several studies have investigated either combined femur fractures with vascular injury or long bone fractures and vascular injuries from gunshot wounds, few have focused on only femur fractures with vascular injuries from gunshot wounds. The purpose of this study was to retrospectively investigate the experience at one urban level‐one trauma center with these injuries and to examine the implication of surgical sequence with regards to short‐term complications and ischaemia time.

Materials and Methods

The medical records of all patients admitted to Temple University Hospital, a level one trauma center in Philadelphia, PA, from January 1996 to December 2005 were searched for the following combination of injuries: gunshot wound, vascular injury, femur fracture. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for this study. Patients with gunshot wounds and vascular injury in a limb other than the limb with the femur fracture were excluded. High‐energy gunshot injuries, such as those by shotgun, were excluded. All femoral fractures, including pertrochanteric and supracondylar femur fractures were included if accompanied by vascular injury. Major venous injuries were also included if accompanied by ipsilateral femur fractures.

Data were recorded directly from chart review to a database with ID numbers assigned to each patient. Patient age, sex, and mechanism of injury were recorded. The type of fracture (e.g. femoral shaft, supracondylar, etc.) as well as the type of vascular injury (e.g. superficial femoral artery transaction, superficial femoral vein transaction, etc.) was noted. The method used to diagnose the vascular injury was noted in all cases. Multiple time points were measured: (i) time from injury until arrival in the emergency department; (ii) time from injury until diagnosis of vascular injury; (iii) time from injury until re‐vascularization completed; (iv) time from injury until fracture stabilization; (v) total surgical time; and (vi) length of stay. The incidence of fasciotomies, whether prophylactic or for compartment syndrome, were noted. The surgical sequence of events with regards to orthopaedic and vascular intervention was recorded. Finally, complications such as compartment syndrome, amputation, vascular repair disruption, and death were recorded.

Results

Thirty‐one patients with femoral fractures, gunshot wounds, and vascular injury were identified by the search of the medical records. Five patients were excluded due to femoral fractures in an opposite limb from the vascular injury. These were patients with multiple gunshot injuries resulting in femur fractures on one limb and vascular injuries without fractures in the other limb. One patient had a shotgun injury and was therefore excluded. Finally, one patient with multiple low velocity gunshot wounds to bilateral lower extremities was excluded due to intraoperative death. This patient presented without a palpable blood pressure and had injuries to the left common femoral artery and bilateral common femoral veins. The patient expired in the operating room before revascularization was completed and fracture stabilization. This left a total of 24 patients for further consideration.

The mean age was 31.3 years (median 29, range 17–71). All injuries were characterized as low‐velocity gunshot wounds. The anatomic location of the femur fractures included: femoral shaft (12 cases), the pertrochanteric region (five cases), and the supracondylar region (seven cases). Vascular injury location included the superficial femoral artery (six cases), superficial femoral vein (three cases), superficial femoral artery and vein (three cases), popliteal artery (four cases), popliteal artery and vein (five cases), profunda femoris artery (three cases), external iliac vein (one case).

Arteriograms were used preoperatively for diagnosis in three cases, whereas arteriogram was performed intraoperatively in six cases. The diagnosis was made in most cases by the clinical findings of pulselessness and negative arterial Dopplers, pulsatile bleeding, or massive haematoma in patients with penetrating wounds in proximity to major extremity vessels.

Because of the perceived importance of surgical sequence, we stratified our data according to the surgical sequence of events in a similar fashion to that of McHenry et al.10 The three main groups encompass the three main modes of treatment commonly described: orthopaedic fixation followed by vascular repair/reconstruction (Group 1), vascular repair/reconstruction followed by orthopaedic fixation (Group 2), and vascular shunting followed by orthopaedic fixation followed by vascular repair/reconstruction (Group 3). We also decided to include patients who did not fall into any of these categories (Group 4). These mainly included patients with major venous injuries or arterial injuries treated by interventional radiology (e.g. profunda femoris branches). Time to revascularization, time until fracture stabilization, and total surgical time for all four groups were outlined in Table 1 and the order of intervention of each patient, respective to each group, is shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Time for revascularization, fracture stabilization, and total surgical time for all patients

| Groups | Mean minutes until revascularization (median) | Mean minutes until fracture stabilization (median) | Mean total surgical minutes (median) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 3) | 550 (660) | 390 (405) | 380 (360) |

| Group 2 (n = 12) | 315 (285) | 1826 (545) | 468 (390) |

| Group 3 (n = 4) | 233 (210) | 435 (375) | 810 (720) |

| Group 4 (n = 5) | 217 (210) | 620 (500) | 475 (480) |

Note: Group 1: Orthopaedic fixation followed by vascular repair/reconstruction; Group 2: Vascular repair/reconstruction followed by orthopaedic fixation; Group 3: Vascular shunting followed by orthopaedic fixation followed by vascular repair/reconstruction; Group 4: Patients who did not fall into any of three categories above.

Table 2.

List of the various orders of intervention in four groups

| Groups | Various orders of intervention |

|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 3) | Orthopaedic repair, then vascular repair (three patients) |

| Group 2 (n = 12) |

Vascular repair, then external fixation, finally orthopaedic repair (one patient) Vascular repair, then external fixation (two patients) Vascular repair, external fixation, revision of repair or vascular injury, and finally orthopaedic repair (one patient) Vascular repair, then orthopaedic repair at a later date (one patient) Vascular repair, then orthopaedic repair (six patients) Vascular repair, then orthopaedic external fixation the next day (one patient) |

| Group 3 (n = 4) |

Vascular shunt, then orthopaedic repair and finally vascular repair (two patients) Vascular shunt, then external fixation, then vascular repair and finally orthopaedic repair (two patients) |

| Group 4 (n = 5) |

Orthopaedic repair only (two patients) Orthoapedic repair, then vascular repair (one patient) Vascular repair, then orthopaedic repair (two patients) |

Note: Group 1: Orthopaedic fixation followed by vascular repair/reconstruction; Group 2: Vascular repair/reconstruction followed by orthopaedic fixation; Group 3: Vascular shunting followed by orthopaedic fixation followed by vascular repair/reconstruction; Group 4: Patients who did not fall into any of three categories above.

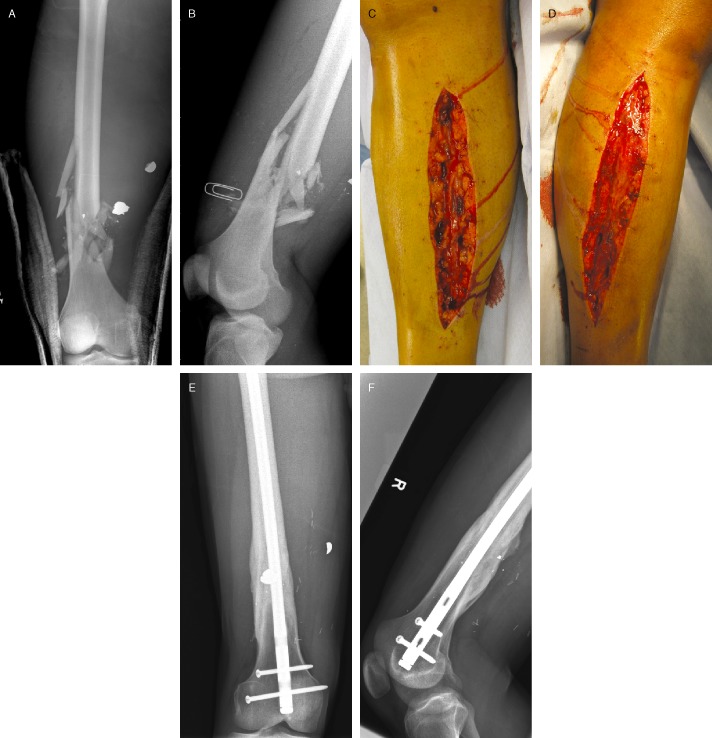

Eleven of the 24 patients underwent prophylactic fasciotomies (Fig. 1). Complications included two revised vascular repairs, five compartment syndromes, and one below knee amputation. One patient also developed acute renal failure and one patient developed a superficial wound infection. The complications were outlined in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Patient with low velocity gunshot injury to distal femur with vascular injury treated with vascular repair followed by fasciotomy of the leg followed by retrograde femoral nailing. (A, B) Anteroposterior and lateral X‐rays showed distal femoral fracture. The patient was also found to have a superficial femoral arterial injury. Photographs showing prophylactic fasciotomy with medial (C) and lateral (D) dual incisions done after vascular repair demonstrated significant muscle bulging, likely indicative of the development of compartment syndrome. The muscle tissue, however, was viable. (E, F) X‐rays one year after operation demonstrated femoral fracture healed with a retrograde femoral nail in place. Multiple vascular clips were also noted.

Table 3.

Complications in all groups

| Groups | Complications (number) |

|---|---|

| Group 1 (n = 3) | No complications |

| Group 2 (n = 12) | Leg compartment syndromes (2), thigh compartment syndrome (1), revision vascular repair (2), foot drop (2), fasciotomy wound infection (1) |

| Group 3 (n = 4) | Compartment syndrome (1), acute renal failure (1) |

| Group 4 (n = 5) | Peripheral neuropathy (1), compartment syndrome (1), below knee amputation (1) |

Note: Group 1: Orthopaedic fixation followed by vascular repair/reconstruction; Group 2: Vascular repair/reconstruction followed by orthopaedic fixation; Group 3: Vascular shunting followed by orthopaedic fixation followed by vascular repair/reconstruction; Group 4: Patients who did not fall into any of three categories above.

Though there were several complications as listed in Table 3, the rate of limb salvage was excellent regardless of the sequence of surgical intervention. The lack of complications in Group 1 is likely due to the small number of patients. The long time to revascularization in this group (Table 1) is due to late diagnosis and presentation. One patient in this group had a late diagnosis of a vascular injury, which turned out to be a pseudoaneurysm treated with vascular reconstruction. Another patient had a delayed presentation after being transferred from another institution. Nevertheless, this patient was treated with orthopaedic fixation first. It is unclear why this decision was made because the time to revascularization is alarmingly long as shown in Table 3. We should mention that we do not advocate orthopaedic fixation first in the face of a delayed diagnosis or presentation even though these two patients did well in the short term.

Complications were numerous in Group 2, in which vascular repair was performed first, followed by orthopaedic fixation. Though 11 of the 24 patients in this study did have prophylactic fasciotomies, three patients in this group who did not have prophylactic fasciotomies developed compartment syndrome and subsequently had fasciotomies. Perhaps more notable is the incidence of two patients in which the vascular reconstruction had to be revised after orthopaedic fixation. At the time of writing this manuscript, we have treated another patient who would have been placed in Group 2 who also had a revision of a vascular reconstruction after orthopaedic fixation. Though this danger has been recognized as a theoretical risk of manipulating and pulling an unstable limb out to length, which has a fresh vascular repair or reconstruction; other studies have not reported this complication. In our series, it did not appear that there were any immediate sequelae directly attributed to the need for revision vascular repair or reconstruction.

One patient in Group 3 had only one kidney, and subsequently developed acute renal failure, which resolved after fluid resuscitation. One patient in Group 4 had severe neurovascular injuries from the gunshot wound (popliteal, tibial, peroneal arteries and veins, tibial nerve) and underwent intramedullary (IM) nailing of the femur and a below knee amputation due to the extent of injuries.

Discussion

This study represents the largest group of low velocity gunshot femur fractures with vascular injury reported in the English literature to our knowledge. We feel that the current controversies regarding this injury center on the proper surgical sequence of events.

Surgical sequence of intervention has long been a controversy in the management of these injuries1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 14, 16. There have been advocates of vascular intervention first as well as fracture fixation first. In a recent study, McHenry retrospectively reported on 27 patients with both lower and upper extremity gunshot injuries with fracture and vascular injury over a 10‐year period10. They stratified patients into three groups that were identical to our Groups 1–3. There were no cases of vascular repair disruption after fracture fixation in 22 cases. Four of five patients who underwent orthopaedic fixation before revascularization required fasciotomies while only eight of 22 patients who were revascularized first required fasciotomies. They therefore concluded that revascularization should be done before orthopaedic fixation. It should be pointed out again, however, that this study included only 16 lower extremity injuries and the anatomic locations were not mentioned. The shortening and subsequent traction required to reduce a femoral fracture can be considerably more than that for a humerus or tibia fracture.

Many other studies have supported the claim that orthopaedic fixation should be done after vascular repair. Menzoian retrospectively reported in 1982 on 56 patients with vascular injuries below the inguinal ligament, some without fractures11. Fifteen of these patients had fractures (four of the femur) and the vascular injuries included all mechanisms. They advocated generous use of external fixation and performed vascular repair both before and after orthopaedic fixation with presumably similar results. However, they clearly advocated the revascularization of patients with severely ischaemic limbs prior to orthopaedic fixation. Ashworth et al. retrospectively reported in 1988 on 25 patients with vascular injuries of the lower extremity, 12 of which had fractures with only two of these being femoral fractures1. Two fractures required external fixation before revascularization due to gross instability. Otherwise, vascular repair was done first followed by orthopaedic fixation. A 96% limb salvage rate was reported with 84% of patients ambulating independently. Their conclusion is that vascular repair should be done before orthopaedic stabilization, even though they acknowledge that in cases of gross displacement or instability that external fixation may need to be done first. Wiss et al. also reported on five patients with gunshot femur fractures and vascular injury treated with IM nailing after vascular reconstruction5. All the fractures united without any vascular insufficiency.

In contrast, Starr et al. examined 26 patients with femur fractures and vascular injuries; 13 patients had gunshot injuries while the rest were from blunt trauma4. External fixation was used in six patients who generally had high MESS (Mangled Extremity Severity Score) and ISS (Injury Severity Score) scores and could not undergo an IM nailing procedure. Ten patients had IM nailing done before vascular repair while nine patients had IM nailing done after vascular repair. They noted equivalent limb salvage rates whether the fixation was performed before or after vascular repair. In a related study, Nowotarski et al. reported on 54 patients with femur fractures treated with temporary external fixation, eight of whom had vascular injury13. These eight patients underwent rapid unilateral external fixation to bring the fracture out to length prior to definitive revascularization. Patients were brought back to the operating room at approximately 7 days for conversion to an intramedullary nail with good clinical results.

There were no incidences of limb loss in the present study regardless of the sequence of surgical intervention. Nevertheless, the 23% incidence of compartment syndrome in patients who did not undergo prophylactic fasciotomy indicates the likely need for more prophylactic fasciotomies in these patients. Also, two patients in this study and the more recent patient mentioned earlier had vascular reconstructions revised after orthopaedic fixation due to disruption attributed to manipulation and lengthening. Though there were no obvious immediate sequelae from either of these complications, these are only a few cases and the long‐term consequences are unknown. In light of the recognition of disrupted vascular repairs reported in Group 2, we have now shifted towards more use of the technique of rapid external fixation followed by vascular repair/reconstruction whenever possible. Recognition of the disrupted repair is important to diagnose while the patient is still on the operating room table. External fixators can be safely converted to IM nails in the face of a vascular repair if done at approximately 7–10 days. This has been shown in studies by both Iannacone et al.9 and Nowotarski et al.13

Arterial shunting as a temporary measure is somewhat controversial but was successful in this series as well as in other studies14, 17. Certainly, the group in this study with the shortest revascularization times was Group 3, in which arterial shunting was performed. Venous shunting can also be performed, if possible. However, shunting does lead to increased operative times as shown in Table 1.

Mention should be made of the diagnosis of arterial injury in this study. All three cases that had preoperative arteriogram were found to have profunda femoris arterial injuries that were treated with interventional radiologic haemostatic methods. In six cases, arteriography was done intraoperatively. It is our opinion that patients with so‐called “hard signs” of vascular injuries such as loss of pulse, pulsatile bleeding, or expanding haematoma in cases of penetrating injuries with large vessel proximity should go to the operating room immediately. In proximity cases with abnormal examination but without hard signs, a trip to the angiography suite may be appropriate. Twenty‐one of 24 cases in this study went directly from the emergency room to the operating room.

The few numbers of patients and retrospective nature of this and other studies on this topic make treatment recommendations difficult. In order to improve the statistical significance of the data, we are currently performing a meta‐analysis of the literature to help pool the data on this uncommon injury pattern. Furthermore, we are developing a prospective study in order to more accurately gather data and be able to examine sequelae with longer follow‐up. Issues such as fracture healing, vascular claudication, and late ischaemia can be examined in comparison to a control group.

Gunshot femur fractures with vascular injuries are limb‐threatening injuries that can be treated appropriately with interdisciplinary intervention between trauma surgeons, orthopaedic surgeons, and vascular surgeons. The rate of limb loss does not appear to be affected by the sequence of surgical intervention. However, revascularization of a grossly unstable limb does pose a real risk of vascular repair disruption after subsequent fracture fixation. This surprisingly has not been previously reported. The reason that the issue of surgical sequence has been controversial is partly due to the fact that significant differences have not been noted in outcomes in this or other studies. Furthermore, this is a rare condition and these studies have been retrospective and do not have statistical power from which to draw clinical and statistical significance. We advocate an individualized approach to each case with ischaemia time kept in mind and a goal of revascularization by 6 h post‐injury. In unstable femur fractures that are diagnosed and brought to the operating room early, rapid external fixation followed by definitive repair is likely the best option. However, in cases of severe ischaemia or delayed diagnosis, definitive repair or shunting followed by fracture fixation is probably a better sequence to pursue. Therefore, the answer is not ortho first or vascular repair first, but rapid revascularization preferably in a stable limb.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest. No benefits in any form have been, or will be, received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1. Ashworth EM, Dalsing MC, Glover JL, et al Lower extremity vascular trauma: a comprehensive, aggressive approach. J Trauma, 1988, 28: 329–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DiChristina DG, Riemer BL, Butterfield SL, et al Femur fractures with femoral or popliteal artery injuries in blunt trauma. J Orthop Trauma, 1994, 8: 494–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Howard PW, Makin GS. Lower limb fractures with associated vascular injury. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1990, 72: 116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Starr AJ, Hunt JL, Reinert CM. Treatment of femur fracture with associated vascular injury. J Trauma, 1996, 40: 17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wiss DA, Brien WW, Becker V Jr. Interlocking nailing for the treatment of femoral fractures due to gunshot wounds. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1991, 73: 598–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abou‐Sayed H, Berger DL. Blunt lower‐extremity trauma and popliteal artery injuries: revisiting the case for selective arteriography. Arch Surg, 2002, 137: 585–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fried G, Salerno T, Burke D, et al Management of extremity with combined neurovascular and musculoskeletal trauma. J Trauma, 1978, 18: 481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guerrero A, Gibson K, Kralovich KA, et al Limb loss following lower extremity arterial trauma: what can be done proactively? Injury, 2002, 33: 765–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Iannacone WM, Taffet R, DeLong WG Jr, et al Early exchange intramedullary nailing of distal femoral fractures with vascular injury initially stabilized with external fixation. J Trauma, 1994, 37: 446–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. McHenry TP, Holcomb JB, Aoki N, et al Fractures with major vascular injuries from gunshot wounds: implications of surgical sequence. J Trauma, 2002, 53: 717–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Menzoian JO, LoGerfo FW, Doyle JE, et al Management of vascular injuries to the leg. Am J Surg, 1982, 144: 231–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nanobashvili J, Kopadze T, Tvaladze M, et al War injuries of major extremity arteries. World J Surg, 2003, 27: 134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nowotarski PJ, Turen CH, Brumback RJ, et al Conversion of external fixation to intramedullary nailing for fractures of the shaft of the femur in multiply injured patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 2000, 82: 781–788. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nunley JA, Koman LA, Urbaniak JR. Arterial shunting as an adjunct to major limb revascularization. Ann Surg, 1981, 193: 271–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Payne WK 3rd, Gabriel RA, Massoud RP. Gunshot wounds to the thigh. Evaluation of vascular and subclinical vascular injuries. Orthop Clin North Am, 1995, 26: 147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rich NM, Metz CW Jr, Hutton JE Jr, et al Internal versus external fixation of fractures with concomitant vascular injuries in Vietnam. J Trauma, 1971, 11: 463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Richardson JB Jr, Jurkovich GJ, Walker GT, et al A temporary arteriovenous shunt (Scribner) in the management of traumatic venous injuries of the lower extremity. J Trauma, 1986, 26: 503–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]