Key Points

Question

What is the consistency of surgical quality across hospitals that are affiliated with the 2018 US News & World Report Honor Roll hospitals?

Findings

In this population-based study of 87 hospitals and 143 174 patients, outcomes were not consistently better at Honor Roll hospitals. Within networks, the risk-adjusted rates for all outcomes varied widely across affiliated hospitals; for example, the differences in failure to rescue varied by 1.1-fold in some networks to as much as 4.9-fold in others.

Meaning

Surgical outcomes vary widely within hospital networks; networks should monitor outcomes to characterize and improve the extent to which a uniform standard of care is being delivered.

Abstract

Importance

Hospitals are rapidly consolidating into regional delivery networks. To our knowledge, whether these multihospital networks leverage their combined assets to improve quality and provide a uniform standard of care has not been explored.

Objective

To evaluate the extent to which surgical outcomes varied across hospitals within the networks of the highest-rated US hospitals.

Design, Settings, and Participants

This longitudinal analysis of 87 hospitals that participated in 1 of 16 networks that are affiliated with US News & World Report Honor Roll hospitals used data from Medicare beneficiaries who were undergoing colectomy, coronary artery bypass graft, or hip replacement between 2005 and 2014 to evaluate the variation in risk-adjusted surgical outcomes at Honor Roll and affiliated hospitals within and across networks. The data were analyzed between April 20, 2018, and June 25, 2018.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Thirty-day postoperative complications, mortality, failure to rescue, and readmissions.

Results

Of 143 174 patients, 68 718 (48.0%) were men, 124 427 (86.9%) were white, and the mean (SD) age was 71.8 (9.9) years and 73.5 (9.1) years in Honor Roll and affiliated hospitals, respectively. Outcomes were not consistently better at Honor Roll hospitals compared with network affiliates. For example, Honor Roll hospitals had lower failure to rescue rates (13.3% vs 15.1%; odds ratio, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86-0.98) but higher complication rates (22.1% vs 18.0%; odds ratio, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.03-1.19). Within networks, risk-adjusted outcomes varied widely across affiliated hospitals. The differences in failure to rescue varied by as little as 1.1-fold (range, 12.7%–14.3%) in some networks to as much as 4.9-fold (range, 7.6%–37.3%) in others. Similarly, complication rates varied by 1.1-fold (range, 21%–23%) to 4.3-fold (range, 6%–26%) across all networks.

Conclusions and Relevance

Surgical outcomes vary widely across hospitals affiliated with the US News & World Report Honor Roll hospitals. Public reporting mechanisms should provide patients with information on the quality of all network-affiliated hospitals. Networks should monitor variations in outcomes to characterize and improve the extent to which a uniform standard of care is being delivered.

This population-based study examines the degree of variation of risk-adjusted surgical outcomes across hospitals within networks that were affiliated with US News & World Report Honor Roll hospitals.

Introduction

Hospital network participation has doubled over the past decade.1 This trend is presenting hospitals with new opportunities to reduce delivery costs through strategic resource allocation, increase administrative efficiency, or establish regional centers of excellence for specialty services.2 In addition to these advantages derived from economies of scale, it is also common for networks to advertise improvements in the quality and consistency of patient care as an important consequence of consolidating their clinical service lines.3

However, it remains unclear whether these multihospital networks are able to deliver a uniform standard of care. While some networks may provide consistent outcomes, others may offer disparate levels of quality across affiliated hospitals despite sharing the same mission or brand. There are many strategies by which hospital networks can improve the outcomes by redesigning care delivery. For example, networks may choose to concentrate complex services at specialized referral centers or, in contrast, export the delivery models that drive quality at high-performing hospitals to their remaining affiliates.4 Moreover, the ability of affiliated hospitals to provide consistent outcomes could serve as a measure of network quality and be used to benchmark strategies that are designed to optimize care delivery.

To explore the variation in outcomes across hospital networks, we conducted a population-based study of Medicare beneficiaries who were undergoing 1 of 3 common inpatient surgical procedures that represented a different service line within hospitals. We hypothesized that there would be substantial variation in outcomes across network hospitals that were affiliated with those named to the US News & World Report Honor Roll, which is an established, highly visible system for ranking hospitals based on various domains of quality.

Methods

Data Source and Study Population

We extracted data from the 100% Medicare Provider Analysis and Review files from 2005 to 2014. We collected patient data, including age, demographic information, and comorbidities. We identified patients who were undergoing colectomy, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), or hip replacement using Diagnosis Related Group codes (329-331, 231-236, and 469-470) and International Classification of Disease, Ninth or Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9 or ICD-10) codes for colectomy (17.31-17.36, 17.39, 45.71-45.76, 45.79, and 45.80-45.83), CABG (36.10-36.17 and 36.19), and hip replacement (81.51). We excluded patients younger than 65 years or older than 99 years and linked patient and hospital-level data to the American Hospital Association Annual Survey to obtain additional information on hospital characteristics, such as bed size or nonprofit status. Those with missing data (<1%) were excluded from the analysis. This study was deemed exempt by the institutional review board at the University of Michigan and patient consent was waived (eFigure in the Supplement).

We used several resources to define the hospital networks associated with the US News & World Report Honor Roll hospitals. First, we identified hospitals named to the 2017 to 2018 Honor Roll.5 These hospitals are the primary tertiary referral centers and represent the name and brand that identify each network. Next, we used data from the American Hospital Association databases (2005-2014) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality compendium of health systems to identify all remaining affiliated hospitals that were associated with each network.6 All hospital affiliations were confirmed independently using publicly available data from each network’s web presence. We used the Honor Roll rankings instead of specific surgical rankings because we sought to explore outcomes across different service lines that were not all captured under a more granular ranking (eg, gastrointestinal surgery). The goal of using the US News & World Report Honor Roll was to capture reputable hospitals (and networks) but not to make specific critique on the ranking system itself.

Outcomes

We used ICD-9-CM/ICD-10-CM codes to identify 30-day postoperative complications, which included pulmonary failure (518.81, 518.4, 518.5, and 518.8), pneumonia (481, 482.0–482.9, 483, 484, 485, and 507.0), myocardial infarction (410.00–410.91), deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism (415.1, 451.11, 451.19, 451.2, 451.81, and 453.8), renal failure (584), surgical site infection (958.3, 998.3, 998.5, 998.59, and 998.51), gastrointestinal bleeding (530.82, 531.00–531.21, 531.40, 531.41, 531.60, 531.61, 532.00–532.21, 532.40, 532.41, 532.60, 532.61, 533.00–533.21, 533.40, 533.41, 533.60, 533.61, 534.00–534.21, 534.40, 534.41, 534.60, 534.61, 535.01, 535.11, 535.21, 535.31, 535.41, 535.51, 535.61, and 578.9), and hemorrhage (998.1). These complications represent a subset of ICD-9 codes with the highest sensitivity and specificity, as has been previously described.7 Serious complications were defined as the incidence of a coded complication and a length of stay greater than the 75th percentile for each procedure.8 We identified deaths as those occurring within 30-day of the index operation. Failure to rescue was defined as a death occurring in a patient with at least 1 documented complication.9,10 Readmissions were identified as any claim for a readmission to the hospital within 30 days after discharge.

Statistical Analysis

The purpose of this analysis was to characterize variations in surgical outcomes across hospital networks. To account for differences in patient characteristics and case mix, we fit multilevel logistic regression models, accounting for patient age, sex, 27 Elixhauser comorbidities, and procedure specific measures (eg, using laparoscopy for colectomy) as fixed effects and hospital-level random effects. We further accounted for overall time trends toward better outcomes using the claim year as a categorical dummy variable. We did not model any interaction terms. The model fit was assessed using C statistics, which ranged from 0.72 to 0.94 for all models. We then estimated risk-adjusted outcome rates at the hospital level, differentiating Honor Roll and affiliated hospitals when reporting the data. We performed sensitivity analyses to confirm the robustness of our findings, repeating the primary analysis for each procedure and after accounting for the time each hospital participated in their network. We accounted for time in network by including a categorical dummy variable for the number of years each affiliated hospital was a member of its network. We further tested for time trends by replicating the analysis for 3 discrete years individually (2005, 2009, and 2014). All statistical analyses were performed using Stata, version 14 (Stata Corp). We used a 2-sided approach at the 5% significance level for all hypothesis testing.

Results

The descriptive characteristics of patients undergoing surgery within Honor Roll and affiliated hospitals are detailed in Table 1. Patients’ burden of comorbid diseases was similar between Honor Roll and affiliated hospitals. For example, 43 084 patients (65.1%) had 2 or more comorbidities at Honor Roll hospitals compared with 50 514 (65.6%) at affiliated hospitals (odds ratio [OR], 0.99; 95% CI, 0.83-1.17). However, the proportion of emergent operations was higher at Honor Roll (17.7%) vs affiliated hospitals (13.4%; OR, 1.26; 95% CI 1.13-1.39). Honor Roll and affiliated hospitals performed a similar proportion of colectomy operations (37.0% vs 35.4%, respectively; OR, 1.1; 95% CI, 0.72-1.43), whereas Honor Roll hospitals performed comparatively more CABG (29.2% vs 16.7%; OR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.66-2.00) and fewer hip replacements (33.9% vs 47.9%; OR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.72-0.85) than affiliated hospitals. Table 1 also shows characteristics associated with each network. Networks, on average, contained 8 affiliated hospitals and represented all geographic regions in the United States.

Table 1. Patient and Hospital Characteristics at Honor Roll and Affiliated Hospitals.

| Patient Characteristics | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Honor Roll Hospitals (n = 19) | Affiliated Hospitals (n = 87) | |

| Patients, No. | 66 150 | 77 024 |

| Demographics | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 71.8 (9.9) | 73.5 (9.1) |

| Male | 34 135 (51.6) | 34 583 (44.9) |

| White | 56 322 (85.7) | 68 105 (89.0) |

| African American | 6155 (9.3) | 6029 (7.8) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Hypertension | 40 524 (61.3) | 49 478 (64.2) |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 14 295 (21.6) | 15 310 (19.9) |

| Diabetes | 11 505 (17.4) | 13 769 (17.9) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 9843 (14.9) | 12 733 (16.5) |

| Renal failure | 6788 (10.3) | 6171 (8.0) |

| Obesity | 7810 (11.8) | 8334 (10.8) |

| Elixhauser comorbidities | ||

| 0 | 6782 (10.3) | 7728 (10.0) |

| 1 | 16 284 (24.6) | 18 782 (24.4) |

| ≥2 | 43 084 (65.1) | 50 514 (65.6) |

| Type of admission | ||

| Elective | 48 636 (73.5) | 58 642 (76.1) |

| Urgent | 5692 (8.6) | 7931 (10.3) |

| Emergent | 11 690 (17.7) | 10 350 (13.4) |

| Procedural characteristics | ||

| Colectomy | 24 468 (37.0) | 27 252 (35.4) |

| Annual hospital volume, mean (SD) | 204 (93.5) | 73 (38.7) |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 19 291 (29.2) | 12 847 (16.7) |

| Annual hospital volume, mean (SD) | 167 (101.5) | 45 (48.6) |

| Hip replacement | 22 391 (33.9) | 36 925 (47.9) |

| Annual hospital volume, mean (SD) | 198 (131.3) | 110 (72.0) |

| Hospital characteristics | ||

| Bed size, mean (SD) | 1163 (498) | 405 (209) |

| Nurse-to-patient ratio, mean (SD) | 2.7 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.6) |

| Annual admissions, mean (SD) | 50 631 (20 237) | 18 753 (10 345) |

| Annual volume of inpatient surgery, mean (SD) | 20 255 (8394) | 5773 (3343) |

| Network Characteristics | ||

| Total networks | 16 | |

| Affiliated hospitals per network, mean (SD) | 8 (6) | |

| Geographic region | ||

| Midwest | 3 (18.8) | |

| Northeast | 7 (43.8) | |

| South | 2 (12.5) | |

| West | 4 (25.0) | |

Certain outcomes were better at Honor Roll hospitals compared with affiliated hospitals. For example, failure-to-rescue rates were lower at Honor Roll hospitals (13.3%; 95% CI, 13.0%-13.6%) compared with affiliated hospitals (15.1%; 95% CI, 14.7%-15.6%; OR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.86-0.98). In total, mean risk-adjusted failure-to-rescue rates were lower for Honor Roll hospitals in 12 of 16 networks (75%). In contrast, risk-adjusted complication rates were higher at Honor Roll hospitals (22.1%; 95% CI, 21.7%-22.3%) compared with affiliated hospitals (18.0%; 95% CI, 17.7%-18.2%; OR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.03-1.19), and this observation occurred in 9 of 16 networks (56%).

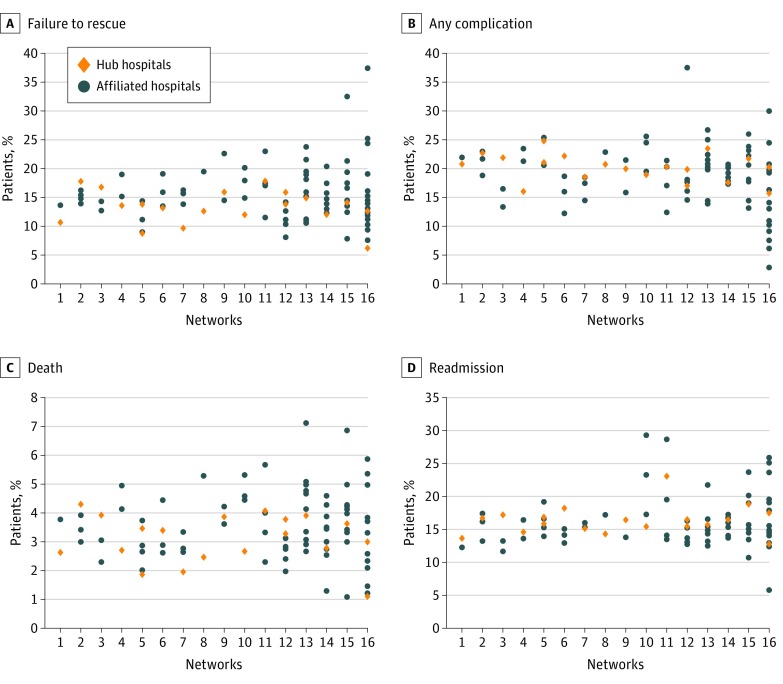

Within networks, risk-adjusted outcome rates at affiliated hospitals varied widely. (Figure, A-D) In some networks the differences in failure to rescue varied by as little as 1.1-fold (range, 12.7%–14.3%) while it varied as much as 4.9-fold (range, 7.6%–37.3%) in others. Compared with the variation that was observed in failure to rescue, other risk-adjusted outcome rates varied less or to a similar extent. For example, readmission rates at affiliated hospitals varied by 1.1-fold (range, 11.6%–13.3%) in one network to 2.8-fold (range, 9.1%–25.8%) in another. Complication rates varied by 1.1-fold (range, 21%–23%) to 4.3-fold (range, 6%–26%). Finally, mortality rates at affiliated hospitals varied by 1.1-fold (range, 3.9%–4.2%) to 4.1-fold (range, 1.4%–5.8%) within individual networks.

Figure. Scatterplot of Mean Risk-Adjusted Outcomes for Honor Roll and Affiliated Hospitals Across the 16 Networks.

A-D, Networks are displayed in the same position on each plot.

In each sensitivity analysis that accounted for time in network or overall time trends, model estimates were similar to our primary analysis. For example, within-network ranges were similar when restricting the analysis to affiliated hospitals with at least 3 years of network participation. In this analysis, failure-to-rescue rates differed by 4.7-fold (range, 7.1%–33.4%) for the network with the most variation. Compared with the main analysis, results were also similar for complications (4.5-fold; range, 7.1%–32.0%), readmissions (2.7-fold; range, 9.8%–26.2%), and mortality (3.8-fold; range, 1.6%–6.0%).

The results from the primary analysis were also consistent across sensitivity analyses performed for each individual procedure (Table 2). For example, failure-to-rescue rates at affiliated hospitals varied by as much as 3.7-fold (range, 3.0%–11.1%) in one network for hip replacement to as much as 6.0-fold (range, 2.3%–13.7%) in another network for CABG. Similarly, mortality rates varied by 4.9-fold (range, 1.1%–5.4%) following CABG to 10.0-fold (range, 0.1%–1.0%) for hip replacement. Overall, outcomes were more variable across affiliated hospitals within networks compared with Honor Roll hospitals across networks.

Table 2. Risk-Adjusted Outcome Rates and Ranges Within and Across Networks for Each Procedure.

| Procedure | Mean Risk-Adjusted Rates (95% CI) | Network-Level Variation, Fold Difference (Range) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Honor Roll Hospitals | Affiliated Hospitals | Across Networks Honor Roll Hospitals | Affiliated Hospitals Within Network | ||

| Minimum | Maximum | ||||

| Colectomy | |||||

| Failure to rescue | 18.1 (17.8-18.2) | 20.7 (19.8-21.6) | 3.3 (7.1-23.1) | 1.1 (22.2-24.6) | 3.8 (8.1-30.9) |

| Any complication | 31.8 (30.7-31.9) | 30.4 (30.1-30.8) | 1.6 (24.4-40.2) | 1.1 (28.2-29.7) | 2.8 (17.6-48.7) |

| Death | 6.9 (6.7-7.1) | 8.2 (8.1-8.2) | 2.8 (3.4-9.6) | 1.2 (9.2-10.8) | 5.5 (2.6-14.4) |

| Readmission | 21.8 (21.2-22.4) | 19.5 (19.3-19.7) | 1.8 (16.4-28.9) | 1.1 (20.5-22.6) | 3.1 (11.7-36.8) |

| Coronary Artery Bypass Graft | |||||

| Failure to rescue | 5.0 (4.9-5.1) | 6.0 (5.8-6.2) | 3.4 (2.6-8.9) | 1.1 (5.1-5.5) | 6.0 (2.3-13.7) |

| Any complication | 30.3 (29.4-31.2) | 28.2 (26.5-29.5) | 2.0 (20.4-41.1) | 1.1 (20.7-21.8) | 4.4 (11.2-49.8) |

| Death | 2.0 (1.9-2.1) | 2.1 (1.9-2.3) | 3.2 (1.3-4.1) | 1.1 (2.1-2.4) | 4.9 (1.1-5.4) |

| Readmission | 19.3 (19.1-19.5) | 17.0 (16.7-17.3) | 2.7 (10.4-28.1) | 1.1 (15.5-17.8) | 2.1 (17.5-36.4) |

| Hip Replacement | |||||

| Failure to rescue | 2.2 (2.1-2.3) | 3.4 (3.0-3.7) | 4.8 (1.3-6.2) | 2.0 (2.9-5.8) | 3.7 (3.0-11.1) |

| Any complication | 4.7 (4.2-5.2) | 4.6 (4.4-4.8) | 2.4 (2.8-6.6) | 1.0 (3.4-3.5) | 7.0 (2.7-19.0) |

| Death | 0.3 (0.2-0.4) | 0.03 (0.2-0.4) | 10 (0.1-1.0) | 1.3 (0.03-0.04) | 10 (0.1-1.0) |

| Readmission | 9.6 (9.1-10.1) | 9.7 (9.3-10.1) | 1.5 (7.4-11.1) | 1.0 (8.6-8.8) | 3.5 (5.8-20.4) |

Discussion

This national population-based study found that risk-adjusted surgical outcomes varied widely across hospitals within networks that were affiliated with US News & World Report Honor Roll hospitals. Moreover, the degree of variation was significantly higher in certain networks compared with others. In other words, some provided consistent quality care for surgical procedures across all affiliated hospitals, whereas others provided disparate levels of quality despite sharing the same brand. These findings were consistent across each procedure, reflecting variability in clinical quality over 3 discrete clinical service lines. This wide variation in outcomes suggests that multihospital networks are not realizing the potential to leverage their combined resources to optimize these service lines across the entire clinical delivery system.

To our knowledge, there is little prior research that assesses whether the quality of care is uniform across hospital networks. Although limited by a lack of empirical data, many believe that hospital networks are able to capitalize on economies of scale and minimize waste and administrative inefficiencies, thereby reducing delivery costs through streamlined supply-chain operations and integrating services across a wider range of clinicians.2,3 Beyond these gains in efficiency, there are opportunities to affect the quality of patient care through system-wide improvements in clinical processes and outcomes. For example, when networks are organized around a high-performing medical center (eg, a US News & World Report Honor Roll hospital), the processes that facilitate high-quality care could potentially be exported to their affiliates. Exporting best practices to affiliated hospitals may then translate into improvements in clinical outcomes. However, without any measures that differentiate networks (eg, an Honor Roll hospital plus its affiliates) based on overall performance, it is not possible to characterize the consistency of quality across an organized group of hospitals.

Differentiating networks based on their outcomes could identify specific opportunities to understand how hospital affiliations influence clinical quality. Networks may achieve better collective outcomes by centralizing care at particular referral centers for rare conditions, high-risk patients, or volume-sensitive procedures.11,12 In this scenario, higher or more variable adverse event rates would manifest in networks that fail to restrict complex services to hospitals with limited experience managing complications or to those that lack specific resources, such as 24-hour intensivist staffing or access to interventional radiology.13 In contrast, networks that seek to expand services across their affiliated hospitals would need to increase the capacity of their services to respond to adverse events to improve outcomes.14 However, in either example networks that fail to critically evaluate their service lines to align expertise and resources appropriately will demonstrate more variability in quality across their affiliates. Beyond service-line reorganization, it will be increasingly important for networks to determine how to integrate clinicians into these multihospital quality improvement efforts. Clinician input is critical to all aspects of delivery system redesign, but may be particularly relevant to quality improvement. Information on the specific changes networks make to individual services lines is not currently available. Nonetheless, we observed extensive differences in the degree of variability across networks, implying that some are integrating services to deliver a more uniform quality experience across the network.

Strengths and Limitations

There are several limitations of this study. It is possible that our results are not generalizable to the entire patient population cared for within each network because our analysis was restricted to Medicare beneficiaries. However, these beneficiaries constitute most patients for these procedures because each underlying disease process is more common in elderly adults. It is also possible that case complexity at Honor Roll hospitals is greater despite our attempts to risk-adjust each outcome. This could alter the interpretation of our results. Honor Roll hospitals may actually perform better because patients are sicker than what is measured in claims data. Affiliates may have better outcomes because the severity of complications is different at each type of hospital based on underlying illness severity. The time in which hospitals participate in their network may also be a factor. We attempted to address this in 2 ways: (1) by accounting for network experience in our models and (2) by repeating our analysis in specific years. It is also possible that our results are limited because we do not account for case volume and adjustment for hospital-level random effects alone will not account for this possibility. However, it is unclear whether volume shifts may be associated with network affiliation itself. In this latter case, volume would act as an effect modifier and therefore would not be amendable to conventional adjustment in the model. Finally, it is possible that restricting our analysis to US News & World Report Honor Roll hospitals and their affiliates restricts the relevance of our results to a narrow demographic of hospitals and clinicians. However, academic medical centers like the Honor Roll hospitals are now involved in more than 20% of all hospital mergers.15 These medical centers also transfer their highly regarded reputations to the hospitals with which they affiliate. Understanding quality within and across these networks may therefore be particularly important to consumers.

Hospital networks are not currently accountable for the overall quality or consistency of clinical services across all of their affiliated hospitals. Although quality improvement may not be the initial motivation for network affiliation, high-quality hospitals that lend their reputation to affiliates should have a vested interest in improving care delivery across their networks. Measuring variation in outcomes offers a framework on which networks can monitor the consistency of their performance, reduce variation in clinical outcomes, and be more strategic about how they leverage collective resources and optimize the delivery of medical and surgical care. For example, networks should think critically about where certain complex procedures are being performed. Networks choosing to expand services across more affiliated hospitals can use coordinated peer-to-peer collaborative improvement plans in which hospitals learn from the experience of the Honor Roll hospital or other centers with the best outcomes. In this context, the practices of high-performing affiliates, such as training staff to recognize and appropriately manage complications, are teachable or exportable to the entire network.16 Networks can also use this framework to inform strategic investments in personnel and resources to optimize safety and reduce variation across their affiliates. Greater attention to these issues may ensure that hospitals maximize the clinical potential of their business relationships and uphold promises of better quality amidst ongoing consolidation.

Conclusions

The quality of complex surgical care varies widely across hospitals affiliated with the US News & World Report Honor Roll hospitals. Tracking outcomes at affiliated hospitals may be an opportunity to drive changes in the overall quality, safety, and consistency of care within newly formed regional delivery networks.

eFigure. Patient Selection Flow Diagram

References

- 1.Schmitt M. Do hospital mergers reduce costs? J Health Econ. 2017;52:74-94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai TC, Jha AK. Hospital consolidation, competition, and quality: is bigger necessarily better? JAMA. 2014;312(1):29-30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dafny LS, Lee TH. The good merger. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(22):2077-2079. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1502338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibrahim AMD, Dimick JB Redesigning the delivery of specialty care within newly formed hospital networks. https://catalyst.nejm.org/redesigning-specialty-care-delivery/. Accessed September 24, 2018.

- 5.US News & World Report The best hospitals 2017-18 honor roll. https://health.usnews.com/best-hospitals. Accessed February 28, 2018.

- 6.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Compendium of US health systems. https://www.ahrq.gov/chsp/compendium/index.html. Accessed February 20, 2018.

- 7.Iezzoni LI, Daley J, Heeren T, et al. Identifying complications of care using administrative data. Med Care. 1994;32(7):700-715. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199407000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimick JB, Nicholas LH, Ryan AM, Thumma JR, Birkmeyer JD. Bariatric surgery complications before vs after implementation of a national policy restricting coverage to centers of excellence. JAMA. 2013;309(8):792-799. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Variation in hospital mortality associated with inpatient surgery. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1368-1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0903048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silber JH, Williams SV, Krakauer H, Schwartz JS. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with death after surgery: a study of adverse occurrence and failure to rescue. Med Care. 1992;30(7):615-629. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199207000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghaferi AA, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Hospital volume and failure to rescue with high-risk surgery. Med Care. 2011;49(12):1076-1081. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182329b97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waits SA, Sheetz KH, Campbell DA, et al. Failure to rescue and mortality following repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(4):909-914.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.10.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagendran M, Dimick JB, Gonzalez AA, Birkmeyer JD, Ghaferi AA. Mortality among older adults before versus after hospital transition to intensivist staffing. Med Care. 2016;54(1):67-73. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheetz KH, Krell RW, Englesbe MJ, Birkmeyer JD, Campbell DA Jr, Ghaferi AA. The importance of the first complication: understanding failure to rescue after emergent surgery in the elderly. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219(3):365-370. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.02.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauptman PJ, Bookman RJ, Heinig S. Advancing the research mission in a time of mergers and acquisitions. JAMA. 2017;318(14):1321-1322. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.11812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghaferi AA, Dimick JB. Understanding failure to rescue and improving safety culture. Ann Surg. 2015;261(5):839-840. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eFigure. Patient Selection Flow Diagram