Abstract

Lumbar posterior ring apophysis fracture (PRAF) is an uncommon cause of low back pain in the pediatric age group, and a detailed understanding of this disease is important for the orthopaedic surgeon because it is easily misdiagnosed. However, to date no comprehensive review of PRAF has been published. The majority of published reports are in the form of cases report generally targeted at either diagnosis or therapy, or both. In this essay, we comprehensively review the pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis and treatment of PRAF.

Keywords: Epiphyseal plate, Intervertebral disk displacement, Low back pain

Introduction

Lumbar posterior ring apophysis fracture is not a common injury and is often overlooked because many orthopaedic surgeons are unfamiliar with this entity. These fractures are mostly traumatic lesions and are typically found in adolescents and young adults; young active athletes in particular are prone to suffer from this disease. It is characterized by separation of bone fragments at the posterior rim of the superior and inferior lumbar vertebral endplate, where the ring apophysis and the adjacent vertebral body are usually incompletely fused, and occurs prior to the age of approximately eighteen years 1 . A variety of terms are also used to refer to this lesion, including limbus vertebra, fracture of the posterior vertebral rim, ring or endplate, epiphyseal dislocation and apophyseal ring fracture or avulsion, slipped vertebral epiphysis, lumbar posterior marginal intraosseous cartilage node, and so on 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 .

Lumbar PRAF occurs in all spinal segments, but the level most commonly affected by apophyseal ring fracture is L4/5 and the most susceptible site for this injury is the posterior inferior endplate of the vertebra 6 , 7 . Dietemann et al. reported the radiological findings in 13 cases of PRAF 6 . The lesion involved the inferior apophyseal ring of L4 in 11 patients, of L5 in one and of L3 in one. In Krishnan et al.'s series of 21 cases of PRAF, the inferior endplate of L4 was involved in nine patients, inferior L3 in five, inferior L5 in two, inferior L1 in one, inferior L2 in one, superior L3 in two and superior S1 in one 8 . Thus these fractures rarely affect the posterior superior area of vertebrae 9 , 10 . Another additional category for apophyseal ring fractures has been proposed, namely, a lesion that is not confined to the superior or inferior margins of the vertebral endplates, but that spans the full length of the vertebral body 2 .

Pathogenesis

As a fetus grows, longitudinal growth of the vertebrae occurs at the epiphyseal plates at the junction of the vertebrae and hyaline cartilage. Outside of the true epiphyseal plates, a cartilaginous ring apophysis (or epiphyseal ring) develops on the outer rims of the superior and inferior surfaces of the vertebral body. The ring apophysis does not participate in longitudinal growth of the vertebral body. The outermost fibers of the annulus, Sharpey's fibers, insert into the ring apophysis, anchoring the intervertebral disc to the adjacent vertebrae. The ring apophysis calcifies at about six years of age, normally begins to ossify at about thirteen years and fuses with the vertebral body at about seventeen years. At eighteen years, fusion appears to be complete. Prior to complete ossification of the ring, the osteocartilaginous junction between the ring and the vertebral body is weaker than the fibrocartilaginous junction between the ring and the disc (formed by the Sharpey's fibers). Thus, shearing stress or repeated trauma may cause apophyseal ring fractures and prolapsed intervertebral discs in adolescents 1 , 11 , 12 .

Most cases of PRAF are reported to occur in the ossification stage of the ring during a period of growth, rather than in the early cartilaginous ring stage. Faizan et al. have clarified the mechanism which explains the high prevalence of this disorder in the ossification stage 13 . They have investigated the effects of ossification of the ring on lumbar spine biomechanics by creating and analyzing two three‐dimensional finite element pediatric lumbar models: one model of ossified apophyseal rings and the other of cartilaginous apophyseal rings. They found that the apophyseal ring is subject to at least twice as much stress in the ossification stage than in the cartilaginous stage, resulting in frequent fractures at the interface of bone and cartilage.

The mechanisms of apophyseal ring fracture are uncertain. There are two possible mechanisms by which the fracture can occur 5 , 8 . Firstly, the force transmitted to the Sharpey's fibers by the nucleus pulposus during herniation may cause disruption at the weak point of the osteocartilaginous junction, thus resulting in an avulsion fracture. Secondly, migration of the nucleus pulposus through the weak point may cause these fractures, similarly to the mechanism which results in a limbus vertebra.

PRAF is always associated with a herniated lumbar disc in young patients 14 , 15 , whereas the ratio of patients who develop intervertebral disc herniation simultaneously with PRAF is less. Therefore, there is a major controversy about whether disc herniation produces avulsion fracture of the apophyseal ring or whether the latter results in annular disruption and disc herniation, or another mechanism is responsible for the pathology.

In the year 2000, Kerttula et al. found that, in young patients with adjacent endplate fractures, the disc space had a significantly increased rate of pathological signal changes on MRI after at least 1 year of follow‐up 16 . Hsu et al. analyzed MRIs from 379 patients to evaluate disc degeneration in the lumbar spine and found that isolated high lumbar disc degeneration was not only associated with preexisting endplate defects, such as in Scheuermann's disease, but also with endplate fractures below or above the respective intervertebral discs 17 . Haschtmann et al. proposed that endplate trauma initiates biological cascades within the intervertebral disc, which could lead to degeneration of this structure 18 .

In order to identify the mechanical reasons for apophyseal ring fracture in pediatric patients, Sairyo et al. developed a three‐dimensional, nonlinear, pediatric, lumbar spine finite element model 19 . Their results indicated that the structures surrounding the growth plate, including the apophyseal bony ring and osseous endplate, were highly stressed as compared to other structures. Furthermore, the posterior structures were in compression during extension whereas they were in tension during flexion, the magnitude of stress being greater in extension than in flexion. Over time, the higher compression stresses along with tension stresses in flexion may contribute to apophyseal ring fracture (fatigue phenomena). Therefore in adolescents, especially in young active athletes, repeated micro traumas caused by great stress, mostly through abrupt extension and weight‐bearing, can injure the epiphyseal cartilage and overload the intervertebral disc 9 . The increase in pressure imposed by the nucleus pulposus on the fibrous annulus may lead to avulsion of bone fragments from the terminal plate following a disc herniation.

However many patients do not recall an episode of trauma prior to occurrence of their symptoms. In addition, some patients report a previous episode of low back pain many years previously 15 . King has provided a possible reasonable interpretation: because the endplate is not innervated, end plate fracture is not typically painful 20 . A person could heal and not even know that they had had such an injury. In addition, trauma may be not the only causative factor; congenital anomalies such as ossification defects of the apophyseal ring 21 and fragility of the endplate 22 also contribute to apophyseal ring fracture.

In some cases, PRAF in adolescence has a strong association with a slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Therefore it has been postulated that a slipped vertebral apophysis invariably occurs in association with a slipped capital femoral epiphysis, and that these conditions may share the same underlying pathophysiology 10 .

Clinical evaluation

The most common symptoms of lumbar PRAF are low back pain, with or without a history of trauma, and radicular pain in one or both legs due to nerve root irritation. Other symptoms and signs include lower lumbar localized tenderness and paravertebral muscle spasm, restricted back movement, a waddling gait with flexed knees, intermittent claudication due to spinal stenosis and sensory disturbance and muscle weakness caused by compressed nerve roots. Cauda equina syndrome presenting with sphincter disturbance has been reported in apophyseal ring fracture. The straight leg raising test may be positive at less than 60o. A systemic enquiry and complete neurological examination is mandatory, as is assessing the Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score for determining appropriate treatment of low back pain 23 .

Diagnosis

Plain radiograph

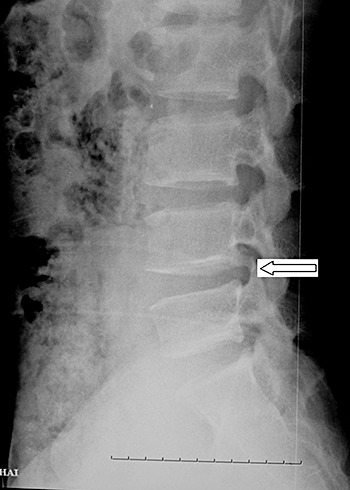

Lumbar PRAF is often occult on plain radiograph, frequently being missed because of the very small size of the fragment or lack of familiarity with this condition, especially when the L5 or S1 vertebra is involved 11 . When the entity is identified on a lateral view radiograph, the findings include a defect in the posteroinferior (or posterosuperior) margin of the affected vertebral body or mild narrowing of the disc space and, behind these defects, an arcuate or wedge shaped bone fragment protruding into the spinal canal 12 , 24 (Fig. 1). A great range of diagnostic accuracy (from 29% to 69%) has been reported when based on radiography alone 6 , 8 , 22 . In Krishnan et al.'s series of 21 patients, which included 16 below the age of 18 years, only six patients could be diagnosed on plain radiography alone 8 . Dietemann et al. reported radiological findings in 13 cases of PRAF 6 . The lesion affected young adults in 10 cases and adolescents in three. Radiological recognition of the lesion was possible on plain radiograph in nine of these cases. Therefore the rate of diagnostic accuracy may be affected by the age of the patient, the level at which the bony fragment has developed, the fragment's shape and size, the quality of the plain film and so on.

Figure 1.

Plain radiograph. The arrow shows a large bone fragment lying in the spinal canal posterior to the lower endplate of the L4 vertebra.

Computed tomography

Computed tomography is the definitive method for demonstration of the size, shape and location of fracture fragments, as well as the presence and extent of the associated disc prolapse, vertebral defect and severity of any associated spinal stenosis 25 (Fig. 2a, b). On CT scanning, the osteocartilaginous fragment has a characteristic arcuate or semilunar configuration that parallels the border of the posterior vertebral body. The fragment may appear irregular rather than arcuate if it contains a large fragment of vertebral body. Takata et al. have classified these fractures into three types on the basis of CT scanning studies 22 and Krishnan et al. has pointed out the correlation of fracture types with age: (i) Type I, is a simple avulsion of the posterior cortex of the endplate, so thin and soft that no obvious defect is present in the vertebral body although an arcuate fracture fragment is visible. This type is found in children younger than 13 years; (ii) Type II, is an avulsion fracture of the posterior rim of the vertebral body, including the overlying cartilage of the annulus fibrosus, resulting in a thicker and larger fragment and it occurs in older children and adolescents; (iii) Type III, is a more localized fracture involving a larger amount of the vertebral body such that the resulting fragment is larger than the vertebral rim. A round defect in the bone adjoining the fracture site is seen 8 . These fractures occur more frequent in people older than 18 years. Epstein et al. proposed an additional category: Type IV, a fracture of both the cephalad and caudad end plates which spans the full length of the posterior margin of the vertebral body 2 . This is a rare pattern. Krishnan et al. reported eight patients between 10 and 14 years of age with type I; four between 13 and 18 years with type II; nine with type III, four of these being under 18 years and rest of the five older than 18 years; and no type IV fractures 8 .

Figure 2.

(a) A bone window and (b) a soft window from a CT scan. The arrows indicate a posterior bony fragment located at the border of the posterior endplate of L4 and a round defect in the bone adjoining the fracture site. This lesion is Type III according to Takata's classification.

Another method of classification has been proposed by Yang et al. on the basis of the shape and location of the fracture and the defect of the vertebral rim 26 . They divided apophyseal ring fractures into two distinct groups: (i) in group 1, the fracture involves the central aspect of the inferior vertebral rim and the bone fragment is large and broad‐based. The great majority of previously reported cases belong to this group; (ii) in group 2, the fracture is located at the posterolateral margin of the superior vertebral rim and the bone fragment is small and focal.

Apophyseal ring fractures are well demonstrated by CT scanning and easily differentiated from posterior longitudinal ligament ossification, herniated disc calcification, and posterior degenerative ridge osteophytes.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Rothfus et al. were the first to review four cases of PRAF of lumbar using MRI 27 . MRI characteristics include: (i) discontinuity and truncation of the postero‐inferior vertebral body; (ii) displacement of a low‐signal avulsed fragment; and (iii) disc protrusion subjacent to the fragment. They concluded that recognition of these findings may eliminate the need for other diagnostic studies. However, many authors express the contrary opinion that lumbar PRAF may be difficult to visualize and therefore easy to overlook on MRI alone 25 (Fig. 3a, b). Compared with the higher sensitivity of CT scanning, MRI only identifies 22% of fractures 28 . Although defects in the posterior vertebral rim are seen clearly on MRI images, avulsed apophyseal fractures may be difficult to detect because their low signals are similar to both cortical bone and the posterior longitudinal ligament. Fragments are more conspicuous on proton density or gradient echo sequences than T1 or T2 weighted images, unless a larger fracture containing marrow is present 27 .

Figure 3.

(a) Sagittal section of T2‐weighted and (b) axial section of MRI demonstrating a huge central disc protrusion of L4/5 and a bone fragment causing severe dual sac compression.

Myelogram

On myelograms, an extradural defect or varying degrees of block of the spinal canal or stenosis at the respective level of affection are frequently present 25 . Myelography followed by CT scanning is still accepted and widely used for operative planning in patients with spinal stenosis; it has a diagnostic accuracy of 91%. The addition of CT scanning after myelograms allows detection of 30% more abnormalities than with myelography alone.

Therapy

Conservative treatment, such as rest, analgesics, anti‐inflammatory agents, modification of activity and physical therapy, should be used initially to manage fractures. Krishnan et al. reported that 12 of 21 patients (57%) responded well to conservative treatment; all eight type I fractures, three of the four type II and only one of nine type III were managed conservatively, and all these had favorable results 8 . He suggested that type I occurs in children younger than 14 years and responds well to a conservative regimen. Type II fracture occurs in somewhat older children, between 14 and 18 years, and they also respond to a conservative regimen with some potentiality for operative treatment. Type III fractures occur in older children and young adults and frequently require surgical treatment. Follow‐up CT scanning of apophyseal ring fractures after conservative treatment show that the fracture fragment becomes re‐united with the vertebral body and at least partly resorbed, rather than causing more extensive ossification 4 .

Many authors regard conservative therapy as an ineffective option in many cases 29 , 30 , and recommend that surgery should be performed once conservative treatment has failed, as evidenced by persistent back pain adversely affecting the patient's ability to function, with or without neurological deficits.

Although there is general agreement on the frequent need for surgery, there is no consensus on the choice of operation. Surgical treatment via the posterior approach consists of performing laminectomy with discectomy and removal of the bone fragment 31 . It is extremely difficult to resect the fragment from an anterior approach; therefore a posterior approach is widely recommended. The fracture fragment is less pliable than the disc material; partial laminectomy is inadequate and total laminectomy is needed for satisfactory excision of the disc and fragment 8 .

Some authors think that adequate exposure of the dura mater, root sleeves and bone fragments can be obtained by resection of only the medial one‐half to one‐third of the lamina at the inferior and superior articular processes 15 . In order to safely and completely remove the bone fragments and protect both root sleeves and the dural sac, a shoe‐shaped double‐ended impactor (Robert Reid, Tokyo, Japan) is recommended for impacting and separating them from the posterior vertebral body margin 15 .

Some authors believe that a partial laminectomy should be performed only on the affected side in order to preserve the facet joints, thus avoiding instability 9 . Release of the compressed root can be performed through a small incision, with minimal damage to ligamentous and muscular structures, using a microscope and a minimally invasive technique. Shirado et al. addressed the question of whether removal of the detached apophyses is mandatory in order to achieve satisfactory results in lumbar disc herniation with separation of the ring apophysis 32 . They prospectively investigated 32 consecutive patients, in whom excision of the herniated disc and mobile bone fragments was performed in 11 patients (34.4%). Discectomy alone was performed in 21 patients (65.6%) with immobile bone fragments. Satisfactory results were obtained in both groups. He draw the firm conclusions that resection of the fragment did not influence the clinical results and was not always needed to achieve satisfactory results.

Epstein et al. emphasize that if the fragment has fused, only decompression can be achieved 28 . However, some patients continue to have low back pain after surgery if the bone fragment has not been removed 33 . Accordingly, some authors hold different views, namely, that removal of the disc alone is not sufficient enough to relieve nerve impingement because the fragment has a space occupying effect which necessitates its removal. If the fragment is untreated or unrecognized, the fracture can heal with residual bony spinal stenosis, which can be labeled as congenital in origin due to unawareness 8 , 34 .

No clear consensus has been reached as to the need for fusion such as posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF), but it should be considered in cases of severe disc degeneration, postoperative segmental spinal instability, and severe stenosis due to posterior central bony spur. Asazuma et al. performed PLIF with autogenous iliac bone, sometimes with hydroxyapatite intervertebral spacers in five cases, because this procedure permits compression of the root sleeves and dural sac, as well as spinal instability, to be simultaneously treated 15 . Kuh et al. selected PLIF with cages as an effective treatment method for restoration of disc space and prevention of foraminal stenosis in cases of lumbar disc disease with a centrally located bony spur in adolescent patients 35 . Though they achieved good results in the small number of patients they reported, it is impossible to draw conclusions from such a small series as to whether the method of PLIF with cages is better than the other methods described above.

Summary

Lumbar PRAF is an uncommon injury which occurs in adolescents and young adults. This injury, often occurring simultaneously with intervertebral disc herniation, may have a close relationship to trauma or repeated micro trauma caused by great stress. CT is a better diagnostic technique for detection of bone fragments, the associated disc prolapse and the extent of any associated spinal stenosis than plain radiograph and MRI. Surgical treatment should be implemented when conservative treatment has failed, and consists of performing wide laminectomy with discectomy and removal of the bone fragment. Fusion by PLIF with cages or autogenous bone may be needed to restore spinal stability.

References

- 1. Bick EM, Copel JW. The ring apophysis of the human vertebra; contribution to human osteogeny. II. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1951, 33: 783–787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Epstein NE, Epstein JA, Mauri T. Treatment of fractures of the vertebral limbus and spinal stenosis in five adolescents and five adults. Neurosurgery, 1989, 24: 595–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Laredo JD, Bard M, Chretien J, et al Lumbar posterior marginal intra‐osseous cartilaginous node. Skeletal Radiol, 1986, 15: 201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beggs I, Addison J. Posterior vertebral rim fractures. Br J Radiol, 1998, 71: 567–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Farrokhi MR, Masoudi MS. Slipped vertebral epiphysis (report of 2 cases). JRMS, 2009, 14: 63–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dietemann JL, Runge M, Badoz A, et al Radiology of posterior lumbar apophyseal ring fractures: report of 13 cases. Neuroradiology, 1988, 30: 337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kurihara A, Kataoka O. Lumbar disc herniation in children and adolescents. A review of 70 operated cases and their minimum 5‐year follow‐up studies. Spine, 1980, 5: 443–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krishnan A, Patel JG, Patel DA, et al Fracture of posterior margin of lumbar vertebral body. India J Orthop, 2005, 39: 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Puertas EB, Wajchenberg M, Cohen M, et al Avulsion fractures of apophyseal ring (“limbus”) posterior superior of the L5 vertebra, associated to pre‐marginal hernia in athletes. Acta Ortop Bras, 2002, 10: 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yen CH, Chan SK, Ho YF, et al Posterior lumbar apophyseal ring fractures in adolescents: a report of four cases. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong), 2009, 17: 85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Leroux JL, Fuentes JM, Baixas P, et al Lumbar posterior marginal node (LPMN) in adults. Report of fifteen cases. Spine, 1992, 17: 1505–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Keller RH. Traumatic displacement of the cartilagenous vertebral rim: a sign of intervertebral disc prolapse. Radiology, 1974, 110: 21–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Faizan A, Sairyo K, Goel VK, et al Biomechanical rationale of ossification of the secondary ossification center on apophyseal bony ring fracture: a biomechanical study. Clin Biomech, 2007, 22: 1063–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chang CH, Lee ZL, Chen WJ, et al Clinical significance of ring apophysis fracture in adolescent lumbar disc herniation. Spine, 2008, 33: 1750–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Asazuma T, Nobuta M, Sato M, et al Lumbar disc herniation associated with separation of the posterior ring apophysis: analysis of five surgical cases and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir (Wien), 2003, 145: 461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kerttula LI, Serlo WS, Tervonen OA, et al Post‐traumatic findings of the spine after earlier vertebral fracture in young patients: clinical and MRI study. Spine, 2000, 25: 1104–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hsu K, Zucherman J, Shea W, et al High lumbar disc degeneration. Incidence and etiology. Spine, 1990, 15: 679–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Haschtmann D, Stoyanov JV, Gédet P, et al Vertebral endplate trauma induces disc cell apoptosis and promotes organ degeneration in vitro . Eur Spine J, 2008, 17: 289–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sairyo K, Goel VK, Masuda A, et al Three‐dimensional finite element analysis of the pediatric lumbar spine. Part I: pathomechanism of apophyseal bony ring fracture. Eur Spine J, 2006, 15: 923–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. King MA. Lumbar vertebral compression, end plate fracture, and disc degradation. Dynamic Chiropractic, 1997, 15: 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martínez‐Lage JF, Poza M, Arcas P. Avulsed lumbar vertebral rim plate in an adolescent: trauma or malformation? Childs Nerv Syst, 1998, 14: 131–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takata K, Inoue S, Takahashi K, et al Fracture of the posterior margin of a lumbar vertebral body. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1988, 70: 589–594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Izumida S, Inoue S. Assessment of treatment for low back pain. J Jpn Orthop Assoc, 1986, 60: 391–394. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cao LB, Zhan AL, Cao QX. Imaging study of lumbar posterior marginal intraosseous node. An analysis of 36 cases. Chin Med J (Engl), 1992, 105: 866–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Peh WC, Griffith JF, Yip DK, et al Magnetic resonance imaging of lumbar vertebral apophyseal ring fractures. Australas Radiol, 1998, 42: 34–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yang IK, Bahk YW, Choi KH, et al Posterior lumbar apophyseal ring fractures: a report of 20 cases. Neuroradiology, 1994, 36: 453–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rothfus WE, Goldberg AL, Deeb ZL, et al MR recognition of posterior lumbar vertebral ring fracture. J Comput Assist Tomogr, 1990, 14: 790–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Epstein NE. Lumbar surgery for 56 limbus fractures emphasizing noncalcified type III lesions. Spine, 1992, 17: 1489–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thiel HW, Clements DS, Cassidy JD. Lumbar apophyseal ring fractures in adolescents. J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 1992, 15: 250–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bonic EE, Taylor JA, Knudsen JT. Posterior limbus fractures: five case reports and a review of selected published cases. J Manipulative Physiol Ther, 1998, 21: 281–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ehni G, Schneider SJ. Posterior lumbar vertebral rim fracture and associated disc protrusion in adolescence. J Neurosurg, 1988, 68: 912–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shirado O, Yamazaki Y, Takeda N, et al Lumbar disc herniation associated with separation of the ring apophysis: is removal of the detached apophyses mandatory to achieve satisfactory results? Clin Orthop Relat Res, 2005, 431: 120–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Konishi H, Torigoshi T, Hara S, et al A clinical study of posterior ring apophyseal separation in childhood. Seikeigeka Saigaigeka, 1991, 40: 198–204. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Banerian KG, Wang AM, Samberg LC, et al Association of vertebral end plate fracture with pediatric lumbar intervertebral disk herniation: value of CT and MR imaging. Radiology, 1990, 177: 763–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kuh SU, Kim YS, Cho YE, et al Surgical treatments for lumbar disc disease in adolescent patients; chemonucleolysis / microsurgical discectomy/ PLIF with cages. Yonsei Med J, 2005, 46: 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]