This cross-sectional study uses National Health Interview Survey data to investigate participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and its association with cost-related medication nonadherence among older adults with diabetes.

Key Points

Question

Is participation of older adults with diabetes in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program associated with reductions in cost-related medication nonadherence?

Findings

In this repeated cross-sectional study of 1302 older adults with diabetes (aged ≥65 years) using National Health Interview Survey data, participants in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program were 5.3 percentage points less likely to report cost-related medication nonadherence compared with eligible nonparticipants, a statistically significant finding.

Meaning

In addition to alleviating food insecurity, food assistance programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program may have a spillover income benefit by helping older adults with diabetes better afford their medications, perhaps by reducing out-of-pocket food expenditures.

Abstract

Importance

Understanding if the association of social programs with health care access and utilization, especially among older adults with costly chronic medical conditions, can help in improving strategies for self-management of disease.

Objective

To examine whether participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is associated with a reduced likelihood of low-income older adults with diabetes (aged ≥65 years) needing to forgo medications because of cost.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This repeated cross-sectional, population-based study included 1302 seniors who participated in the National Health Interview Survey from 2013 through 2016. Individuals in the study were diagnosed with diabetes or borderline diabetes, were eligible to receive SNAP benefits, were prescribed medications, and incurred more than zero US dollars in out-of-pocket medical expenses in the past year. The data analysis was performed from October 2017 to April 2018.

Exposures

Self-reported participation in SNAP.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Cost-related medication nonadherence derived from responses to whether in the past year, older adults with diabetes delayed refilling a prescription, took less medication, and skipped medication doses because of cost. To estimate the association between participation in SNAP and cost-related medication nonadherence, we used 2-stage, regression-adjusted propensity score matching, conditional on sociodemographic and health and health care–related characteristics of individuals. Estimated propensity scores were used to create matched groups of participants in SNAP and eligible nonparticipants. After matching, a fully adjusted weighted model that included all covariates plus food security status was used to estimate the association between SNAP and cost-related medication nonadherence in the matched sample.

Results

The final analytic sample before matching included 1385 older adults (448 [32.3%] men, 769 [55.5%] non-Hispanic white, and 628 [45.3%] aged ≥75 years), with 503 of them participating in SNAP (36.3%) and 178 reporting cost-related medication nonadherence (12.9%) in the past year. After matching, 1302 older adults were retained (434 [33.3%] men, 716 [55.0%] non-Hispanic white, and 581 [44.6%] aged ≥75 years); treatment and comparison groups were similar for all characteristics. Participants in SNAP had a moderate decrease in cost-related medication nonadherence compared with eligible nonparticipants (5.3 percentage point reduction; 95% CI, 0.5-10.0 percentage point reduction; P = .03). Similar reductions were observed for subgroups that had prescription drug coverage (5.8 percentage point reduction; 95% CI, 0.6-11.0) and less than $500 in out-of-pocket medical costs in the previous year (6.4 percentage point reduction; 95% CI, 0.8-11.9), but not for older adults lacking prescription coverage or those with higher medical costs. Results remained robust to several sensitivity analyses.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings suggest that participation in SNAP may help improve adherence to treatment regimens among older adults with diabetes. Connecting these individuals with SNAP may be a feasible strategy for improving health outcomes.

Introduction

Nearly 21% of adults aged 65 years or older have been diagnosed with diabetes, and another 4.4% have not been diagnosed.1 Diabetes is costly to manage; an older adult is estimated to incur $11 825 in annual medical expenses for treating diabetes, with prescription medications accounting for approximately 18% of expenditures.2

Unaffordable health care costs can result in tradeoffs between basic needs such as food and medication, and these tradeoffs can be particularly challenging for low-income adults with diabetes because both food and medication must be addressed to effectively manage the disease. Tradeoffs can manifest as cost-related medication nonadherence, including behaviors such as skipping or stopping medications, receiving smaller doses, or delaying or forgoing filling a prescription, all because of cost. Cost-related medication nonadherence can have adverse consequences for individuals’ health outcomes and health care costs.3,4 Reported cost-related medication nonadherence rates among older adults with diabetes are high, generally ranging from 14% to 30% depending on the sample considered.5

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) is the largest food safety net program in the United States, providing assistance to needy households to purchase food in the form of an electronic benefit card. Although much of the literature on SNAP has focused on studying the program’s effects on food insecurity (its targeted outcome), there has recently been a surge in interest in whether programs such as SNAP, by addressing an important social need, can have spillover benefits on health and health care utilization. For example, a recent study compared health care expenditures between participants in SNAP and eligible nonparticipants and estimated that participation in SNAP was associated with approximately $1400 less in mean annual health care costs.6 One reason for cost savings may be that SNAP could improve disease self-management, conceivably by reducing out-of-pocket expenditures for food that could then be spent for medications.

Using data from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) and a 2-stage, regression-adjusted, propensity score–matching method, this study is the first, to our knowledge, to investigate the relationship between SNAP and cost-related medication nonadherence among older adults with diabetes aged 65 years or older. We hypothesize that by indirectly improving financial access to medications, SNAP may be associated with a lower likelihood of cost-related medication nonadherence. Cost-related medication nonadherence is an important intermediate health outcome and reducing it may contribute to lower health care utilization through avoidable hospital admissions and improved overall health and may result in significant cost savings for health systems and insurers.

Methods

Data Source and Study Sample

We extracted NHIS data for 2013 through 2016 from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series Health Surveys.7 The NHIS is an annual, cross-sectional survey of the US civilian noninstitutionalized population that provides information on a wide range of health status and utilization measures. The NHIS offers a large, nationally representative sample of older adults with information on our 2 variables of interest (cost-related medication nonadherence behaviors and participation in SNAP). The NHIS also provides data on individual- and household-level demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, which are key criteria for a well-developed propensity score–matching analysis. Consent was obtained by the agency collecting NHIS data as specified in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention documentation.8 NHIS public-use data are deidentified to protect the confidentiality of respondents. Because this was a secondary analysis of deidentified, publicly available data, the study does not constitute human subjects research and institutional review board approval was not required.

We limited the study sample to SNAP-eligible adults aged 65 years or older who were prescribed medications in the past year and who reported that they had been diagnosed with diabetes or borderline diabetes by a health professional. We based income eligibility for SNAP on a net income test using household income minus allowable deductions9 (eAppendix 1 in the Supplement). We further restricted the sample to individuals who reported having at least some out-of-pocket medical expenses in the past year because the question of economic tradeoffs and affordability of prescription medication is pertinent to this group. Figure 1 shows the initial NHIS sample of participants, those excluded because of restrictions, and the final matched-groups sample used for analysis.

Figure 1. Development of the Final Sample for Analysis.

SNAP indicates Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Key Variables

SNAP Participation

Participation in SNAP was self-reported by survey respondents. The NHIS asked respondents whether anyone in their household participated in SNAP in the past calendar year. Older adults who responded affirmatively composed the treatment group, whereas the remaining analytic sample of nonparticipants comprised the comparison group.

Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence

We used 3 variables that indicated that individuals did not adhere to their prescription regimen because of cost.10,11 Respondents indicated yes or no to whether in the past year, they delayed refilling a prescription, took less medication, or skipped medication doses to save money. We classified older adults as engaging in cost-related medication nonadherence if they responded affirmatively to any of these questions.

Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Health Care–Related Variables

We controlled for characteristics that have been established in the literature as associated with both cost-related medication nonadherence and SNAP.10,12,13,14,15 We included categories for age (65-69, 70-74, and ≥75 years) and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic other) and dichotomous indicators for sex, US citizenship, marital status (married or cohabiting and single or living alone), region of residence (the southern United States and all other US regions), employment, and educational level (bachelor’s degree or higher and some college or less). We also included the natural logarithm of per capita income and an indicator for food security status (fully food secure and at risk of hunger, based on the 10-item US Adult Food Security Survey Module administered in the NHIS). We considered a household to be fully food secure if the individual responded negatively to all 10 questions. Older adults were considered to be at risk of hunger (ie, experiencing marginal food security or food insecurity) if the individual answered affirmatively to 1 or more questions.16 Health and health care–related characteristics included binary indicators for health status (fair or poor and good, very good, or excellent), past year out-of-pocket medical costs (<$500 and ≥$500), having any functional limitation, and prescription drug coverage (including private plans, Medicaid, and/or Medicare Part D). Because all older adults in the sample had some form of health insurance, variation was noted only in prescription drug coverage.

Statistical Analysis

Using 2-tailed t tests, we compared the proportion of individuals in the unmatched treatment and comparison groups for each characteristic. For the continuous income variable, we compared the mean value between these 2 groups. As anticipated, the 2 groups differed for most characteristics. To control for these differences and potential confounding in estimating the association between SNAP and cost-related medication nonadherence, we used a 2-step propensity score–matching estimation method that is similar to doubly robust methods of estimation.17,18

In the first step, we estimated propensity scores from a logistic regression model in which participation in SNAP was the outcome of interest and model covariates were such that they influence both engaging in cost-related medication nonadherence and participating in SNAP (eg, age and sex) but should not be affected by participation in SNAP (eg, food security). We then used the estimated propensity scores and radius matching with replacement to create matched intervention and comparison groups. In the second step, using a weighted logistic regression model, we examined differences in cost-related medication nonadherence rates between the matched groups of participants in SNAP and eligible nonparticipants. Our approach was based on the recommendations of Stuart,19 who advised that after matching, one may “pool all the matches into matched treated and control groups and run analyses using the groups as a whole, rather than using the individual matched pairs.”17

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of the association between SNAP and cost-related medication nonadherence using the 3 underlying outcomes, alternative matching algorithms, and alternative calculations of SNAP eligibility. We also experimented with models that used comparison groups presumably more similar to the treatment group for unobserved variables that may be correlated with both participation in SNAP and cost-related medication nonadherence but which are not directly measurable from the survey data. A detailed description of our approach and results can be found in eAppendix 2 in the Supplement. The participation in SNAP model results are shown in eTable 1 in eAppendix 3 in the Supplement.

We incorporated the survey weight in both steps of our analysis to increase the comparability between the 2 groups and to estimate the population average treatment effect on the treated, which is generalizable to the target population.20 Specifically, we included the survey weight as a variable in the participation model to account for any relevant factors that were not already captured by other covariates (eg, those related to an individual’s probability of responding to the survey). In the second step, the regression on the matched sample was weighted by the product of the propensity score weight and the survey weight.

All statistical analyses were performed from October 2017 to April 2018 using Stata software, version 14.0 (StataCorp LLC). Two-tailed P < .05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the Study Sample

The final analytic sample included 1385 older adults before matching, of whom 503 participated in SNAP in the past year (36.3%) and 178 reported cost-related medication nonadherence (12.8%) during the same period. Of these 1385 older adults, 448 (32.3%) were men, 769 (55.5%) were non-Hispanic white, and 628 (45.3%) were aged 75 years or older. After matching, of 1302 older adults who were retained, 434 (33.3%) were men, 716 (55.0%) were non-Hispanic white, and 581 (44.6%) were aged 75 years or older. We observed many differences between the treatment and comparison groups before matching. Eligible nonparticipants were more likely to be white, male, and employed, and to have $500 or more in out-of-pocket medical costs, whereas participants in SNAP were more likely to be younger and single or living alone, and to have prescription drug coverage. After the groups were matched and matching weights were applied, these differences were no longer present (Table 1). The results of additional balancing tests confirmed the quality of the matching (eAppendix 4 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Sample Characteristics Before and After Propensity Score Matching, by Participation Status in SNAP.

| Characteristic | Percentagea | P Valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNAP | No SNAP | ||

| Before Propensity Score Matching (n = 1385) | |||

| Older adults, No. (%) | 503 (36.3) | 882 (63.7) | NA |

| Age, y | |||

| 65-69 | 34.9 | 26.5 | <.001 |

| 70-74 | 29.1 | 23.8 | .04 |

| >75 | 36.0 | 49.6 | <.001 |

| Male sex | 26.7 | 37.2 | <.001 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 46.7 | 59.7 | <.001 |

| Hispanic | 18.6 | 13.5 | .01 |

| Non-Hispanic other | 34.7 | 26.8 | .002 |

| US citizen | 96.1 | 97.4 | .16 |

| Single or living alone | 90.5 | 78.6 | <.001 |

| Educational level, bachelor’s degree or higher | 10.1 | 10.1 | .99 |

| Residing in the South | 44.0 | 42.8 | .68 |

| Employed | 2.7 | 4.6 | .08 |

| Natural logarithm of per capita income, mean (SD) | 9.2 (0.5) | 9.3 (0.5) | <.001 |

| Fair or poor health status | 56.2 | 46.2 | <.001 |

| Any functional limitation | 90.3 | 84.6 | .003 |

| Any prescription drug coverage | 87.2 | 79.3 | <.001 |

| ≥$500 in out-of-pocket medical costs | 27.3 | 51.1 | <.001 |

| After Propensity Score Matching (n = 1302) | |||

| Older adults, No. (%) | 480 (36.9) | 822 (63.1) | NA |

| Age, y | |||

| 65-69 | 34.5 | 34.5 | .97 |

| 70-74 | 29.4 | 30.0 | .81 |

| >75 | 36.0 | 35.4 | .85 |

| Male sex | 26.7 | 26.6 | .99 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 46.9 | 45.7 | .71 |

| Hispanic | 18.8 | 18.9 | .93 |

| Non-Hispanic other | 34.4 | 35.3 | .75 |

| US citizen | 96.3 | 96.3 | .94 |

| Single or living alone | 90.4 | 90.7 | .87 |

| Educational level, bachelor’s degree or higher | 10.2 | 10.7 | .82 |

| Residing in the South | 43.8 | 42.3 | .65 |

| Employed | 2.7 | 3.1 | .70 |

| Natural logarithm of per capita income, mean (SD) | 9.2 (0.5) | 9.2 (0.5) | .82 |

| Fair or poor health status | 55.8 | 54.2 | .62 |

| Any functional limitation | 90.2 | 89.9 | .85 |

| Any prescription drug coverage | 87.3 | 86.2 | .62 |

| ≥$500 in out-of-pocket medical costs | 27.5 | 27.4 | .98 |

Abbreviations: NA, not applicable; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Sample weight not shown.

P values are from t tests for equality of means before and after matching, generated during the first stage of the propensity score–matching process. Before matching, t tests are based on an unweighted regression of each variable on the SNAP indicator. After matching, the regression is weighted using the weight generated from the matching process. Because of weighting and potential differences in the sample sizes for each regression, the proportions shown may not always match a simple ratio of the subgroup sample size and total sample size.

SNAP and Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence

Table 2 reports the results of the second-stage logistic regression model. Participants in SNAP had a 5.3 percentage point decrease (95% CI, 0.5-10.0 percentage point decrease; P = .03) in the likelihood of engaging in cost-related medication nonadherence compared with those in the comparison group. With an estimated 16.8% of the matched comparison group engaging in cost-related medication nonadherence in the past year, a 5.3 percentage point decrease is equivalent to a reduction in cost-related medication nonadherence of 31.5% for participants in SNAP. However, the lower bound of the CI is nearing zero, suggesting a moderate association with participation in SNAP.

Table 2. Estimated Percentage Point Difference in Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence Among Older Adults With Diabetes, by Participation in SNAP.

| Variable (n = 1301) | Percentage Point Difference (95% CI)a | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Participation in SNAP, PATT | −5.3 (−10.0 to −0.5) | .03 |

| Age, y | ||

| 65-69 | 14.1 (7.0 to 21.2) | <.001 |

| 70-74 | 3.2 (−3.8 to 10.2) | .37 |

| Male sex | −6.5 (−11.4 to −1.6) | .009 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 0.4 (−4.8 to 5.7) | .87 |

| Hispanic | −12.0 (−16.4 to −7.5) | <.001 |

| US citizen | −0.8 (−18.3 to 16.7) | .93 |

| Single or living alone | −5.9 (−18.0 to 6.1) | .34 |

| Educational level, bachelor’s degree or higher | −2.8 (−10.2 to 4.5) | .45 |

| Residing in the South | −1.4 (−6.3 to 3.5) | .57 |

| Employed | 3.1 (−9.3 to 15.5) | .63 |

| Logarithm of per capita income | 0 (−4.3 to 4.3) | .99 |

| Fully food secure | −15.6 (−21.3 to −9.9) | <.001 |

| Fair or poor health status | 4.7 (−0.1 to 9.5) | .05 |

| Any functional limitation | −0.2 (−10.0 to 9.6) | .97 |

| Any prescription drug coverage | −7.3 (−14.9 to 0.3) | .06 |

| ≥$500 in out-of-pocket medical costs | 7.0 (1.5 to 12.5) | .01 |

Abbreviations: PATT, population average treatment effect on the treated; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Percentage point differences are the average marginal effects from a logistic model. Regression includes a constant and is weighted by the product of the propensity score weight and the survey weight.

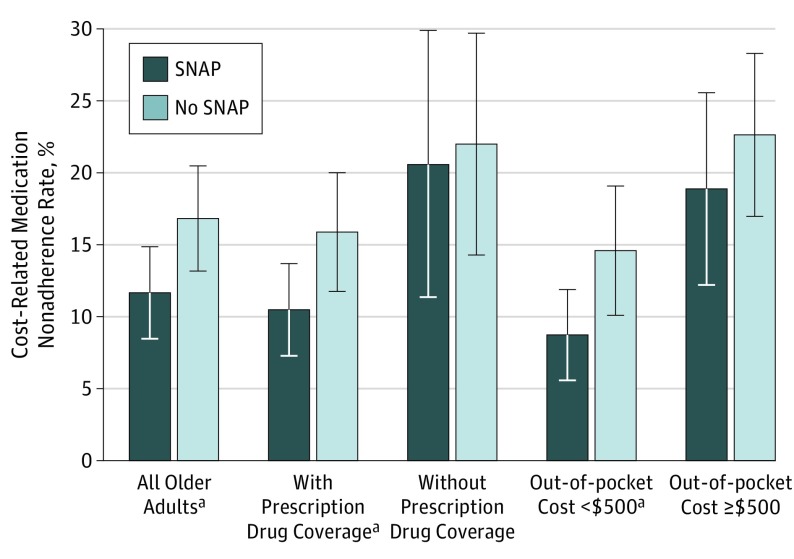

Because prescription drug coverage is one of the most important protective factors against the underuse of medication, we examined the association of SNAP with cost-related medication nonadherence among older adults with and without prescription drug coverage. Among older adults with diabetes and prescription drug coverage, cost-related medication nonadherence rates for participants in SNAP were 5.8 percentage points lower (95% CI, 0.6-11.0 percentage point decrease; P = .03) compared with their nonparticipating counterparts (Figure 2). For those without drug coverage, there was no difference in cost-related medication nonadherence between older adults participating in SNAP and older adults who were eligible but not participating (eTable 4 in eAppendix 5 in the Supplement gives SNAP estimates from subgroup regressions).

Figure 2. Regression-Adjusted Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence Rates for Older Adults With Diabetes Who Did and Did Not Participate in SNAP.

Estimated cost-related medication nonadherence rates include a constant and other covariates from Table 2, and are weighted by the product of the propensity score weight and survey weight. Prescription drug coverage subgroup models omit drug coverage as a covariate, and out-of-pocket cost subgroup models omit out-of-pocket costs as a covariate. The percentage point difference between the cost-related medication nonadherence rates for the treatment and comparison groups represents the population average treatment effect on the treated. SNAP indicates Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Error bars show the 95% CIs.

aStatistically significant population average treatment effect on the treated values at P < .05.

In the main analysis, we found that individuals who had at least $500 in out-of-pocket medical costs in the past year were 7.0 percentage points (95% CI, 1.5-12.5 percentage points; P = .01) more likely to engage in cost-related medication nonadherence compared with individuals with lower medical expenditures. Therefore, we examined the association of participation in SNAP with cost-related medication nonadherence in subgroups of older adults defined by their reported out-of-pocket medical costs. Participation in SNAP was significantly associated with cost-related medication nonadherence only for those with less than $500 in medical costs for the past year (Figure 2). Specifically, participation in SNAP was associated with a 6.4 percentage point decrease (95% CI, 0.8-11.9 percentage point decrease; P = .02) in cost-related medication nonadherence in this group. Although the magnitude of the treatment association was sizeable even among the group with higher medical costs, it lacked statistical significance.

Sensitivity Analysis

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted to test the robustness of our main results (Table 3), and the results of the sensitivity analyses supported the main findings. Across the 3 underlying outcomes of cost-related medication nonadherence, the SNAP estimate was between a 4.6 percentage point reduction (95% CI, 0.1-9.1 percentage point reduction) and a 5.0 percentage point reduction (95% CI, 0.7-9.3 percentage point reduction). Findings also were robust to alternative matching algorithms: nearest neighbor matching with replacement (5.6 percentage point reduction [95% CI, 0.8-10.4 percentage point reduction]) and kernel matching with replacement (5.1 percentage point reduction [95% CI, 0.4-9.9 percentage point reduction]). Recognizing that there is room for error in calculating SNAP eligibility using self-reported secondary data, we sought to ensure that our calculation of SNAP eligibility did not affect the findings. Similar associations were obtained from eligibility calculations based on net household income (excluding the deduction for out-of-pocket medical expenses) and gross household income. The results remained robust to model specifications that used alternative definitions of the treatment group: (1) older adults who participated in SNAP for at least 6 months and (2) only those who participated in SNAP for all 12 months. Participants in SNAP who reported fewer months were included in the comparison group, along with income-eligible nonparticipants, thus making the comparison group plausibly more similar to the treatment group on unobserved variables that may be correlated with both participation in SNAP and cost-related medication nonadherence, but which are not directly measurable from the survey data (eg, stigma associated with participation).

Table 3. Sensitivity Analyses Showing Estimated Percentage Point Differences in Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence Among Older Adults With Diabetes, by Participation in SNAP.

| Sensitivity Test | PATT (95% CI)a | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying outcome variables | ||

| Delayed refilling prescription | −4.6 (−9.1 to −0.1) | .05 |

| Skipped medication doses | −4.9 (−9.2 to −0.5) | .03 |

| Took less medication | −5.0 (−9.3 to −0.7) | .02 |

| Alternative matching algorithm | ||

| Nearest neighbor matching with 15 neighbors | −5.6 (−10.4 to −0.8) | .02 |

| Kernel matching | −5.1 (−9.9 to −0.4) | .03 |

| Alternative SNAP eligibility calculations | ||

| Based on net income excluding medical deductions | −5.4 (−10.2 to −0.5) | .03 |

| Based on gross income | −4.6 (−9.3 to 0) | .05 |

| Alternative treatment and comparison groups | ||

| Participated in SNAP for at least 6 mo | −5.9 (−10.5 to −1.3) | .01 |

| Participated in SNAP for full 12 mo | −5.7 (−10.2 to −1.1) | .02 |

Abbreviations: PATT, population average treatment effect on the treated; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

Estimated PATT values are the average marginal effects from a logistic model and show the percentage point difference in cost-related medication nonadherence between SNAP and non-SNAP participating older adults with diabetes. All regressions include a constant and all other covariates from Table 2 and are weighted by the product of the propensity score weight and the survey weight.

Discussion

This study used propensity score matching to estimate the association between participation in SNAP and engagement of older adults with diabetes in cost-related medication nonadherence. We found that cost-related medication nonadherence rates among participants in SNAP were 5.3 percentage points lower than among eligible nonparticipants, equivalent to a reduction of 31.5% among participants in SNAP. This finding remained robust across a series of sensitivity analyses that explored underlying outcomes and different modeling assumptions. Similar reductions in cost-related medication nonadherence were observed for subgroups that had prescription drug coverage and less than $500 in out-of-pocket medical costs in the previous year but not for subgroups lacking prescription drug coverage or those incurring higher medical costs. These findings seemed counterintuitive because older adults most likely to engage in cost-related medication nonadherence (eg, lacking prescription drug coverage and having high out-of-pocket medical costs) had the most to gain from participation in SNAP. Our results, however, indicate that participation in SNAP was associated with decreases in cost-related medication nonadherence only among older adults with prescription drug coverage and lower medical costs. It seems plausible, however, that the modest value of the SNAP benefit may not be sufficient to overcome the financial struggles of these subgroups in greater need. Further research could investigate the association of the dollar value of the SNAP benefit with outcomes such as cost-related medication nonadherence; this research may help uncover a minimum value of SNAP benefit at which these associations start to be seen. In addition, our study used a binary indicator of cost-related medication nonadherence, although older adults may engage in these behaviors to varying degrees. Using NHIS data, we could not assess whether SNAP may have reduced the level at which older adults engaged in cost-related medication nonadherence; we could only assess whether they engaged in these practices. Further research could explore whether SNAP helps to reduce the frequency of cost-related medication nonadherence in these groups, even if it does not eliminate the behavior entirely.

A small body of previous research has controlled for participation in SNAP in analyses of cost-related medication nonadherence, but participation in SNAP was not a focal variable.12 These studies found that participants in SNAP have significantly higher odds of cost-related medication nonadherence than nonparticipants, but this finding may be a spurious association resulting from the failure to construct an appropriate comparison group. Instead, these studies grouped eligible and ineligible (ie, higher-income) adults. Our findings are consistent with recent research that found that participation in SNAP can reduce health care utilization through avoidable hospital and emergency department visits21 and reduce health care costs.6 We add to this small but growing body of literature by examining the important intermediate health outcome of cost-related medication nonadherence, which is particularly important from a diabetes self-management perspective because medication adherence is critical for avoiding serious complications, such as nephropathy, retinopathy, and neuropathy. This study supports previous findings that suggest that enrollment in SNAP can serve as a strategy for supporting glycemic control among low-income adults with diabetes.22

Although the relationship between SNAP and cost-related medication nonadherence may be of importance for any population, older adults are of particular interest because their participation rate in SNAP has historically been well below that of other adults (approximately 42% in recent years)23 despite efforts to alleviate barriers to enrollment and participation. Many older adults live on fixed incomes and have higher rates of chronic disease than do younger adults. Finally, even though adults aged 65 years or older compose only 13.5% of the US population, they constitute the highest users of health care services in terms of expenditures.24

Quantifying the relationship between SNAP and cost-related medication nonadherence is relevant to multiple stakeholders. Policymakers need to recognize that the provision of health insurance coverage is not fully sufficient to improve the health and well-being of individuals unless access is also ensured to nutritious food and other social supports. Our findings also highlight a potential opportunity cost of suboptimal participation in SNAP among eligible older adults, and federal agencies and other stakeholders should consider efforts to reduce barriers to participation, especially for those who may never have relied on public assistance before retirement from the workforce. An important step in this direction would be to better streamline health and human services programs. For example, all older adults receiving Medicaid could be automatically enrolled in SNAP because beneficiaries are adjunctively eligible. This would eliminate burdensome application requirements that individuals may find challenging. Health professionals may also encourage participation in SNAP by highlighting its health benefits, which could lessen the stigma associated with participation in public assistance programs.

Health systems and payers have a vested interest in connecting low-income patients with food assistance programs given the direct connection between food insecurity and health and a growing body of evidence that suggests that addressing social needs can improve health outcomes and health care utilization. In addition to our findings that suggest better cost-related medication adherence, a recent evaluation of the Health Leads program showed promising improvements in blood pressure and cholesterol levels for patients who were screened for unmet needs and who were connected with a patient advocate to access services.25 Public and private payers could also consider reimbursing clinicians for food security screening and subsequent referral to public assistance programs to reduce health care costs that may arise from cost-related medication nonadherence.

Limitations

This study has a number of methodological limitations. First, the NHIS data are cross-sectional, which limits the ability to determine the association of SNAP with cost-related medication nonadherence. Unable to use more rigorous panel data methods, we used propensity score matching to create a matched comparison group, which served as a counterfactual, or reasonable proxy, for the treatment group if they did not participate in SNAP. Our propensity score–matching framework, however, cannot control for unobserved confounders that may be correlated with both participation in SNAP and cost-related medication nonadherence. For instance, seniors who choose to participate in SNAP may be more likely than nonparticipants to engage in other help-seeking behaviors that could increase their ability to afford needed medications. Although we cannot account for this fully, we experimented with alternative comparison groups that were likely to be more similar to the treatment group in terms of unobserved confounders and our results remained robust.

Self-reported cost-related medication nonadherence and participation in SNAP may be subject to measurement error. Although error in the outcome variable will not lead to bias, the potential underreporting of SNAP (a common issue with survey data) can lead to some participants being included in the comparison group, therefore biasing the results. Without administrative data, it is not possible to quantify the degree of underreporting. Because participants in SNAP are more compliant than nonparticipants in medication use, inclusion of some participants in the comparison group may lower the mean rate of cost-related medication nonadherence for the comparison group. In the absence of such underreporting, the estimated association of participation in SNAP with cost-related medication nonadherence may be even higher. Finally, we did not examine other reasons for medication nonadherence, such as medication-related adverse events or patients remembering to take their medication consistently. However, the ability to afford prescription medications is the first step in an individual’s decision to adhere to a medication regimen.

Conclusions

The study findings suggest that even though SNAP is designed to alleviate hunger by providing financial resources to purchase food, the program may also allow individuals to better afford medications. This benefit, in turn, may be associated with an improvement in overall health and reduction in the burden of high costs faced by health systems. For low-income older patients with diabetes, in particular, these findings offer a potential strategy for improving health outcomes and reducing hypoglycemia: linking patients with social service programs that can help address financial hardship.

Our study points to a number of opportunities for further research. First, research could explore whether modest increases in SNAP benefit allocations could return health care cost savings through better management of chronic diseases, especially for those lacking prescription drug coverage and those with high out-of-pocket health costs. Second, it is important to better understand how other social programs may interact with SNAP and potentially contribute to even more improved rates of cost-related medication nonadherence and other health or health care utilization outcomes. Finally, our estimates relied on repeated cross-sectional data. With the availability of panel data, a more rigorous longitudinal study examining management of diabetes care, out-of-pocket health care costs, and participation in SNAP can be developed.

eAppendix 1. Calculating SNAP Income Eligibility

eAppendix 2. Propensity Score Matching and Regression Specifications

eAppendix 3. Results of the First Stage Regression Model

eAppendix 4. Additional Balancing Tests to Assess Matching Quality

eAppendix 5. Results of Subgroup Regressions

eReferences

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html. Accessed December 30, 2017.

- 2.American Diabetes Association Economic Costs of Diabetes in the US in 2012. Diabetes Care 2013;36(4):1033-1046. http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/36/4/1033. Accessed January 21, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Chen J, Rizzo JA, Rodriguez HP. The health effects of cost-related treatment delays. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(4):261-271. doi: 10.1177/1062860610390352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mojtabai R, Olfson M. Medication costs, adherence, and health outcomes among Medicare beneficiaries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22(4):220-229. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.4.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang JX, Lee JU, Meltzer DO. Risk factors for cost-related medication non-adherence among older patients with diabetes. World J Diabetes. 2014;5(6):945-950. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v5.i6.945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Rigdon J, Meigs JB, Basu S. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) participation and health care expenditures among low-income adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(11):1642-1649. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blewett LA, Rivera Drew JA, Griffin R, King ML, Williams KCW IPUMS Health Surveys: National Health Interview Survey, Version 6.2 [dataset]. Published 2017. Minneapolis, MN. University of Minnesota. https://www.ipums.org/doi/D070.V6.2.shtml. Accessed October 1, 2017. doi: 10.18128/D070.V6.2. [DOI]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2016. National Health Interview Survey. Published June 2017. ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/Dataset_Documentation/NHIS/2016/srvydesc.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2018.

- 9.US Department of Agriculture. Food and Nutrition Service Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). SNAP Special Rules for the Elderly or Disabled. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/snap-special-rules-elderly-or-disabled. Published 2018. Accessed October 14, 2018.

- 10.Afulani P, Herman D, Coleman-Jensen A, Harrison GG. Food insecurity and health outcomes among older adults: the role of cost-related medication underuse. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;34(3):319-342. doi: 10.1080/21551197.2015.1054575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierre-Jacques M, Safran DG, Zhang F, et al. Reliability of new measures of cost-related medication nonadherence. Med Care. 2008;46(4):444-448. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31815dc59a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berkowitz SA, Seligman HK, Choudhry NK. Treat or eat: food insecurity, cost-related medication underuse, and unmet needs. Am J Med. 2014;127(4):303-310.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herman D, Afulani P, Coleman-Jensen A, Harrison GG. Food insecurity and cost-related medication underuse among nonelderly adults in a nationally representative sample. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):e48-e59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kennedy J, Wood EG. Medication costs and adherence of treatment before and after the Affordable Care Act: 1999-2015. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(10):1804-1807. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zivin K, Ratliff S, Heisler MM, Langa KM, Piette JD. Factors influencing cost-related nonadherence to medication in older adults: a conceptually based approach. Value Health. 2010;13(4):338-345. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00679.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bickel G, Nord M, Price C, Hamilton W, Cook J. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security, Revised 2000. Published 2000. Alexandria, VA: US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caliendo M, Kopeinig S. Some practical guidance for the implementation of propensity score matching. J Econ Surv. 2008;22(1):31-72. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6419.2007.00527.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho D, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Polit Anal. 2007;15:199-236. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpl013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stuart EA. Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat Sci. 2010;25(1):1-21. doi: 10.1214/09-STS313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dugoff EH, Schuler M, Stuart EA. Generalizing observational study results: applying propensity score methods to complex surveys. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(1):284-303. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samuel LJ, Szanton SL, Cahill R, et al. Does the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program affect hospital utilization among older adults? The case of Maryland. Popul Health Manag. 2018;21(2):88-95. doi: 10.1089/pop.2017.0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Seligman H. The monthly cycle of hypoglycemia: an observational claims-based study of emergency room visits, hospital admissions, and costs in a commercially insured population. Med Care. 2017;55(7):639-645. https://journals.lww.com/lww-medicalcare/Fulltext/2017/07000/The_Monthly_Cycle_of_Hypoglycemia__An.1.aspx. Accessed June 6, 2018. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farson Gray K, Cunningham K Trends in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation rates: fiscal year 2010 to fiscal year 2015. Published 2017. Washington DC: US Department of Agriculture. Food and Nutrition Service, Office of Policy Support. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/trends-usda-supplemental-nutrition-assistance-program-participation-rates-fiscal-year-2010-fiscal. Accessed March 26, 2018.

- 24.Zayas CE, He Z, Yuan J, et al. Examining healthcare utilization patterns of elderly middle-aged adults in the United States. Proc Int Florida AI Res Soc Conf. 2016;2016:361-366. Medline: 27430035 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berkowitz SA, Hulberg AC, Standish S, Reznor G, Atlas SJ. Addressing unmet basic resource needs as part of chronic cardiometabolic disease management. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(2):244-252. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Calculating SNAP Income Eligibility

eAppendix 2. Propensity Score Matching and Regression Specifications

eAppendix 3. Results of the First Stage Regression Model

eAppendix 4. Additional Balancing Tests to Assess Matching Quality

eAppendix 5. Results of Subgroup Regressions

eReferences