Abstract

Objective: To investigate the characteristics of recurrent fracture of a new vertebral body after percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients with osteoporosis.

Methods: 29 postmenopausal osteoporosis patients were divided into two groups: 14 patients with recurrent fracture of a new vertebral body after vertebroplasty comprised the new fracture group and there were15 patients without recurrent fracture in the control group. The following variables were reviewed: age, body mass index (BMI), history of fractures, history of metabolic disease, anti‐osteoporosis therapy, type of back brace used, bone mineral density (BMD) of the lumbar spine and hip, intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH), serum calcium and phosphorus, and time since vertebroplasty.

Results: Compared with the control group, patients in the new fracture group were statistically significantly different with respect to BMI (t = 2.538, P = 0.027), BMD of the lumbar spine (t = 2.761, P = 0.015), BMD of the hip (t = 2.367, P = 0.037) and iPTH (t = 2.711, P = 0.017). Twelve (86%) of the 14 patients' new vertebral fractures occurred within six months after treatment of the initial fracture, and 10 (71%) fractures were adjacent to those previously treated by percutaneous vertebroplasty.

Conclusions: A substantial number of patients with osteoporosis develop new fractures after vertebroplasty; two‐thirds of these new fractures occur in vertebrae adjacent to those previously treated. The following variables influence the outcome: BMI, history of fractures, history of metabolic diseases and medications, BMD of lumbar spine and hip, anti‐osteoporosis therapy, and use of back brace.

Keywords: Compression, Fractures, Minimally invasive, Osteoporosis, Surgical procedures

Introduction

Vertebral fracture is the commonest osteoporotic fracture, and vertebroplasty is the most commonly used and effective surgical treatment for managing osteoporotic fracture pain. However recurrent fracture after surgery is a common complication which is challenging to address. The purpose of this study was to analyze and discuss the causes and contributing factors in occurrence of recurrent fracture after vertebroplasty, and to highlight the matters that need attention and the corresponding surgical measures that should be implemented.

Materials and methods

Patients

Twenty‐nine postmenopausal osteoporosis patients who had undergone percutaneous vertebroplasty for a single level of vertebral compression fracture participated in our survey. All of them underwent dual energy X‐ray absorptiometry examination which showed that their lumbar spine (L2–4) t‐values were less than −2.5 standard deviations (SD).

Groups

In the new fracture group there were 14 patients with an average age of 67.9 ± 9.7 years (range, 56–77 years) and an average duration of menopause of 18.7 ± 5.9 years with recurrent fracture of a new vertebral body after percutaneous vertebroplasty. In this group, all subjects denied that their recurrent fracture was related to trauma. Fifteen patients with an average age of 69.6 ± 10.8 years (range, 54–79 years) and an average duration of menopause 19.1 ± 7.6 years and without recurrent fracture of a new vertebral body after percutaneous vertebroplasty were selected to comprise the control group. To ensure accuracy and comparability of the vertebral bone mineral density (BMD) measurements, the sites of the original osteoporotic or recurrent fractures of the 29 patients we selected were all in the first lumbar vertebra (L1).

Variables

The following variables were assessed: (i) patient's general characteristics including age, duration of menopause, and body mass index (BMI); (ii) comparison of patient's history of present and past illnesses especially with respect to metabolic disease, multiple fractures, date after vertebroplasty, anti‐osteoporosis and metabolic drug therapy, use of back brace, and so on; (iii) patient's bone densitometry, the BMD of lumber (L2–4) and total hip being assessed by dual energy X‐ray bone densitometry (Lunar‐Dpx‐IQ, GE, Wauwatosa, WI, USA) and the t‐values for lumber spine and hip calculated; and (iv) date and site of the new fracture.

Statistical analysis

Student's t‐test was used for comparison between the two groups of the measurement indexes. All differences are regarded as significant only if P < 0.05. SAS 8.0 statistical software was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Factors influencing recurrent fracture after vertebroplasty

Comparing the new fracture group with the control group, we found that a history of multiple fractures, use of drugs which influence bone metabolism such as glucocorticoids, diseases of the endocrine or immune systems, anti‐osteoporosis therapy after vertebroplasty and application of a lumbar back brace were the factors which correlated with recurrent fracture (Table 1).

Table 1.

Confounding variables of patients in the two groups [cases (%)]

| Factors | New fracture group (n= 14) | Control group (n= 15) |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple fractures | 7 (50) | 2 (13) |

| Use of drugs which influence bone metabolism | 5 (36) | 1 (7) |

| History of metabolic disease | 6 (43) | 1 (7) |

| Multiple vertebral fractures | 5 (36) | 4 (27) |

| Anti‐osteoporosis therapy | 3 (21) | 9 (60) |

| Use of back brace | 2 (14) | 8 (53) |

Comparison of the general characteristics and BMD of patients showed that there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in age, duration of menopause, follow‐up time after vertebroplasty, and serum calcium and phosphate concentrations. However in the new fracture group, the BMI were notably lower than in the control group (P = 0.027), hip and lumbar densities and t‐values were significantly less than in the control group (P < 0.05), and serum parathyroid hormone (PTH) concentrations were greater than in the control group (P = 0.017, Table 2). These results indicate that patients who are thinner, and who have lower BMD of the lumbar spine or hip and higher PTH concentrations have a higher risk of new bone fractures.

Table 2.

BMD and baseline comparison of outcome of patients in the two groups

| New fracture group (n= 14) | Control group (n= 15) | t value | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 64.67 ± 7.10 | 66.08 ± 7.90 | 1.324 | 0.213 |

| Duration of menopause (years) | 13.76 ± 4.50 | 15.09 ± 5.20 | 1.782 | 0.096 |

| BMI (kg/cm2) | 22.79 ± 2.78 | 24.99 ± 3.56 | 2.538 | 0.027 |

| Time since surgery (days) | 476.30 ± 21.83 | 489.06 ± 26.51 | 1.799 | 0.084 |

| L2–4 BMD (g/cm2) | 0.741 ± 0.159 | 0.825 ± 0.147 | 2.761 | 0.015 |

| L2–4 t‐value | −3.20 ± 0.27 | −2.60 ± 0.21 | 2.913 | 0.011 |

| Hip BMD (g/cm2) | 0.647 ± 0.139 | 0.756 ± 0.167 | 2.367 | 0.037 |

| Hip t‐value | −2.30 ± 0.19 | −1.90 ± 0.14 | 2.510 | 0.023 |

| iPTH (pmol/l) | 9.71 ± 0.84 | 5.02 ± 0.25 | 2.711 | 0.017 |

| Serum calcium (mmol/l) | 2.37 ± 0.15 | 2.29 ± 0.18 | 1.997 | 0.610 |

| Serum phosphate (mmol/l) | 1.35 ± 0.11 | 1.49 ± 0.13 | 2.014 | 0.577 |

Time of occurrence of the new fracture

Most new fractures occurred within six months of vertebroplasty. Seven new fractures occurred within 3 months of surgery, five within 3–6 months, one within 6–9 months, and one after 12 months.

Incidence of new fracture in adjacent vertebrae

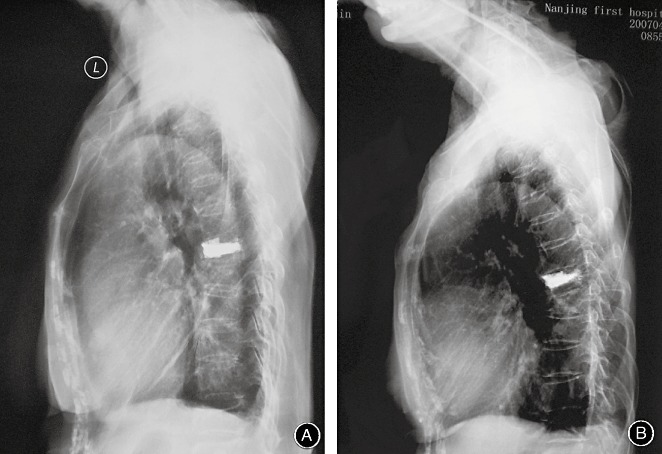

In 10 of the 14 cases (71.4%) the new fracture occurred adjacent to the previously treated vertebra, whereas the rate of non‐adjacent fracture was 28.6% (4 cases). This indicates that new fractures occur much more frequently adjacent to the treated vertebra after vertebroplasty than elsewhere. None of the X‐ray films of the 14 patients with new vertebral fracture showed any leakage of bone cement after vertebroplasty (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Plain lateral radiographs of a 67‐year‐old female patient who experienced acute back pain when she bent over at home. The X‐ray films showed a thoracic vertebral fracture (T6). She then underwent vertebroplasty to relieve her pain, the surgery was successful resulting in good pain relief. When she returned for routine follow‐up on the fortieth day, the X‐ ray films showed a new fracture of T7, immediatley adjacent to her initial fracture. (A) The day of surgery. (B) Forty days after surgery.

Discussion

The new minimally invasive technique of vertebroplasty for treatment of painful osteoporotic vertebral fracture can quickly relieve pain, improve function and restore the integrity of the spine. During 30 years of clinical application, it has achieved satisfactory curative efficacy. However the incidence of new vertebral fracture after surgery is a common clinical problem, having been reported to be 13.68–20.6% 1 , 2 .

The causes of new fracture after vertebroplasty

Osteoporosis, one of the risk factors in fractures of the elderly, makes treatment after fracture difficult, so ways of improving the quality of fracture treatment and preventing new fractures is at the heart of present work on treatment of fractures in the elderly 3 . The reasons for new fractures occurring after vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral fractures can be divided into two categories, the biological causes of osteoporosis and the biomechanics of the vertebroplasty technique. Progression of osteoporosis will result in further deterioration of bone quality, and consequentially lead to recurrent fracture. Vertebroplasty always induces some chemical and physical changes in the skeleton which can lead to new fractures as a result of biomechanical changes. Therefore the incidence of new vertebral fractures after vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral fractures should be analyzed from various angles in order to establish effective methods for preventing recurrent fracture.

Factors related to osteoporosis

Vertebral fracture is the most common osteoporotic fracture, it can occur repeatedly, and is attributed to the osteoporosis itself. So we should assess the severity of the osteoporosis concurrently with undertaking fracture treatment and take care to choose the appropriate surgical measures. The assessment of an osteoporotic fracture and the severity of the osteoporosis should include omnifarious factors, such as the patient's BMI, BMD, bone turnover indexes 4 . Our study suggests that individuals who are thin and who have reduced BMD of the lumbar spine or hip and increased PTH concentrations are at greater risk of new bone fractures after vertebroplasty. Patients with progressive osteoporotic fractures who have obviously abnormal bone turnover indexes, high PTH concentrations or secondary hyperparathyroidism (SHPT) should be prescribed osteoporosis treatment while their fractures are being treated, otherwise not only will fracture healing be delayed, but new fractures will inevitably occur. Studies have showed that the incidence of new fractures varies according to whether the patients receive an anti‐osteoporosis treatment after vertebroplasty 1 . Prescription of glucocorticoids also plays an important role in new fractures 2 .

Factors related to vertebroplasty and countermeasures

As well as comprehensively analyzing the skeletal status and prioritizing assessment of bone turnover indexes and BMD, the whole situation of the patient, including the extent of osteoporosis, should be taken fully into account before instituting surgical therapy. If we focus only on the presenting fracture and ignore the root cause, new fractures will be inevitable postoperatively. It is remarkable that surgery is more effective when a preoperative MRI shows a fresh fracture. Yang et al. have pointed out that selective individual vertebroplasty treatment produces a satisfactory result and prevents recurrent fracture postoperatively 5 .

How to correctly apply filling technology is a key point in surgery involving the use of bone cement. A study of 83 patients, which used logistic regression analysis for 13 different factors to evaluate the relative risks of recurrent compressed fractures, has shown that leakage of bone cement into the discs is the only independent factor that predicts the incidence of new fracture after vertebroplasty 6 . They found that factors such as age, sex, BMD, number of vertebroplasty operations, number of vertebrae operated on during a single procedure, accumulated number of surgically treated vertebrae, presence of a single or multiple untreated vertebrae during surgery, quantity of cement injected each time, accumulated amount of bone cement injected, leakage of bone cement into soft tissue around the vertebra and leakage of cement into veins do not correlate with an increased risk of new fracture 6 . However most scholars believe that multiple factors determine the occurrence of new fracture 1 , 2 , 7 , 8 .

In this study, the new fracture was adjacent to the previously surgically treated vertebrae in 10 of 14 patients (71%). This incidence is significantly higher than for nonadjacent vertebrae. Hulme et al. analyzed their results and pointed out that kyphoplasty and partial vertebroplasty can restore the height of the compressed vertebra 7 . Their rates of bone cement leakage after vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty were 41% and 9%, respectively 7 . The incidence of adjacent vertebral fractures after these two operations is higher than for general osteoporosis patients, yet close to that of patients with a history of vertebral fracture. A study from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston found that, among 177 patients who had undergone vertebroplasty, 22 (12.4%) experienced a total of 36 new vertebral fractures, among which 24 new fractures (67%) occurred adjacent to the previously surgically treated vertebra, while the other 12 (33%) were in non‐adjacent vertebrae. They believed the reason for this disparity was that percutaneous vertebroplasty can reinforce a vertebra and increase its rigidity. This change in rigidity might create increased disparity in the rigidity of neighboring vertebrae, alter the distribution of pressure between them, and thus increase the risk of fracture of adjacent vertebrae 8 . In studies of biomechanical changes in adjacent vertebrae after kyphoplasty with calcium phosphate cement, scholars have confirmed that the stress and strain values increase differently in the adjacent intervertebral discs, non‐enhanced vertebrae and back structures including the posterior vertebral bodies and the pedicles of the vertebral arches; and the increment of non‐enhanced vertebrae is most significant. The influence of enhanced vertebrae to the neighboring vertebrae is similar, which may lead to the highest incidence of new fracture 9 .

Our study suggests that the rate of new fractures is higher in the first six months after vertebroplasty than at other times, 12 of the 14 patients (86%) experienced new fractures within six months of surgery. Uppin et al. reported that, of 36 new fractures, 24 (67%) occurred within 30 days of the first fracture therapy 8 . Komemushi et al. found that the rate of new fractures within 90 days of vertebroplasty was about 10% 6 . Therefore, great importance should be attached to preventing new fractures in the first six, especially the first three, months after vertebroplasty.

Other measurements

With regard to osteoporotic therapy, application of a back brace and rehabilitation activities can also significantly affect the incidence of new vertebral fractures after vertebroplasty. In this study, treatment of osteoporosis and application of a back brace were implemented much more often in the control group. Because of the rapid improvement in symptoms after vertebroplasty, patients may undertake inappropriately strong physical activities, which can be another cause of recurrent fracture 8 . However when patients perform exercises for the waist muscles, especially the back extensor muscle, after vertebroplasty, the incidence of new fractures is markedly decreased 10 .

In conclusion, the incidence of new vertebral fractures is related not only to osteoporosis itself but also to the influence of the vertebroplasty. The first three months after vertebroplasty is an important time window. The hip and vertebral BMD, treatment of anti‐osteoporosis, use of a back brace, and correct rehabilitation training are also important factors affecting the incidence of new vertebral fractures.

References

- 1. Lavelle WF, Cheney R. Recurrent fracture after vertebral kyphoplasty. Spine J, 2006, 6: 488–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Syed MI, Patel NA, Jan S, et al Symptomatic refractures after vertebroplasty in patients with steroid‐induced osteoporosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2006, 27: 1938–1943. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huang GY. Clinical treatment of geriatric fractures to be improved (Chin). Zhonghua Chuang Shang Gu Ke Za Zhi, 2004, 6: 961–962. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lin H, Bao LH, Han ZB, et al The effects of calcitonin treatment on bone quality in patients with osteoporosis (Chin). Zhonghua Gu Ke Za Zhi, 2001, 21: 519–521. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang HL, Gu XH, Chen L, et al Selectivity and individualization of transpedicular balloon kyphoplasty for aged osteoporotic spinal fractures (Chin). Zhongguo Yi Xue Ke Xue Yuan Xue Bao, 2005, 27: 174–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Komemushi A, Tanigawa N, Kariya S, et al Percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteoporotic compression fracture: multivariate study of predictors of new vertebral body fracture. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol, 2006, 29: 580–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hulme PA, Krebs J, Ferguson SJ, et al Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty: a systematic review of 69 clinical studies. Spine, 2006, 31: 1983–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Uppin AA, Hirsch JA, Centenera LV, et al Occurrence of new vertebral body fracture after percutaneous vertebroplasty in patients with osteoporosis. Radiology, 2003, 226: 119–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mao HQ, Yang HL, Chen L, et al Biomechanical evaluation of kyphoplasty with calcium phosphate cement (Chin). Suzhou Da Xue Xue Bao, 2007, 27: 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huntoon EA, Schmidt CK, Sinaki M. Significantly fewer refractures after vertebroplasty in patients who engage in back‐extensor‐strengthening exercises. Mayo Clin Proc, 2008, 83: 54–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]