Introduction

Giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath (GCTTS) is known to be a benign, slow growing tumor originating in tendon sheath or soft tissue. In earlier descriptions, Jaffe et al. regarded GCTTS, pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) and the rare pigmented villonodular bursitis as belonging to a spectrum of lesions 1 . More recently it has been concluded, on the basis of clinical, evidence‐based diagnoses and histological observations, that GCTTS is a distinct type of neoplasm possessing a unique set of characteristics 2 .

GCTTS may occur at any age. The ages of patients range from 6 to 65 years, with a mean age of 32.04 years. The peak incidence is between 20 and 29 years, a second peak being observed at 40–49 years 3 . The tumor is known to be uncommon in children. However, recently several cases have been reported in children 4 , 5 . It has a predilection for female patients, over 67% occurring in women and girls 6 . No racial predominance has been reported. GCTTS is the second most common soft tissue tumor of the hand after ganglion cyst 7 . Other sites, such as the feet and knees, can also be involved 8 , 9 , 10 .

Symptoms of GCTTS are nonspecific and include pain, joint swelling and limitation of movement 11 . The commonest sign is a palpable, painless mass that has been present for several weeks to years. The tumor is locally aggressive and can erode adjacent bone by pressure 12 . It has a high recurrence rate (up to 44%) after excision and occasionally invades adjacent structures 13 , 14 . To minimize the risk of recurrence, a well‐planned operation following an accurate preoperative diagnosis and an evaluation of local tumor extent is required.

In this study, we evaluated the clinical, histologic and immunohistochemical findings in two rare cases of GCTTS on the tip of the toe treated in our institution. Kirschner wire, curettage or radiotherapy was selected according to the different characteristics of the two cases. Presentation of these two rare clinical cases may be beneficial for clinicians.

Case reports

Case 1

A 34‐year‐old Chinese man presented with a 1.5 cm × 0.5 cm, nonmobile, soft mass on the plantar aspect of his left second toe which had been present for 12 months prior to presentation. His previous history was normal with no medical problems or surgeries.

Plain radiography showed an opacity around the proximal part of the left second toe without bone destruction (Fig. 1). MRI showed a mass centered on the dorsolateral aspect of the mid diaphysis of the left second toe (Fig. 2), the mass encircling the flexor tendons on theplantar surface and being adjacent to the extensor tendons on the dorsal surface.

Figure 1.

Plain radiograph showing an opacity around the proximal left second toe with no bone destruction.

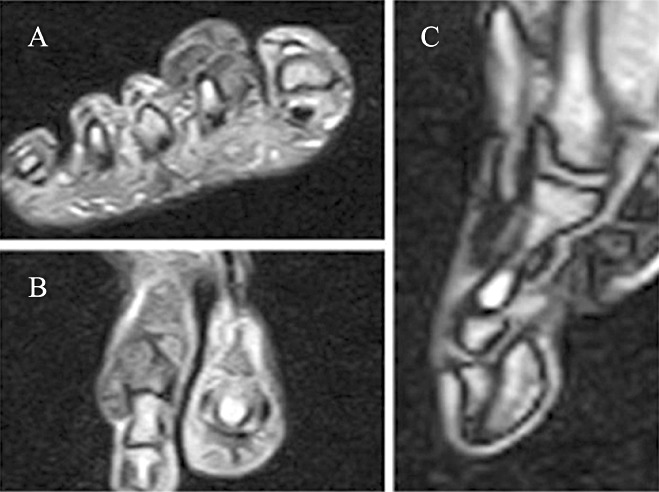

Figure 2.

(A) Axial MRI showing a soft‐tissue tumor divided by some membranes on the dorsal and medial aspects of the second toe with a characteristic low signal on T1 weighted image. (B) Coronal plane MRI displaying the soft‐tissue tumor separated by a pseudomembrane bulging on both sides of the second toe. (C) Sagittal plane MRI displaying the soft‐tissue tumor around the plantar and dorsal aspects of the second toe with a characteristic low signal on T1 weighted image.

After an incisional biopsy, resection was undertaken, revealing a soft mass measuring 1.5 cm × 0.5 cm × 0.5 cm which involved the flexor tendons of the second toe. A marginal resection was performed at this site removing all gross tumor but sparing the tendons. The proximal interphalangeal joint was unstable, so a Kirschner wire was driven across the proximal interphalangeal joint to fix it (Fig. 3). The Kirschner wire was removed 4 weeks later.

Figure 3.

Plain radiograph showing an antegrade smooth Kirschner wire which has been driven across the proximal interphalangeal joint.

Histopathological examination resulted in a diagnosis of GCTTS (Fig. 4) and immunohistochemical staining for cluster of differentiation 68 (CD 68) was positive (Fig. 5). At 12 months after surgery, there was no recurrence and the patient's activity was normal.

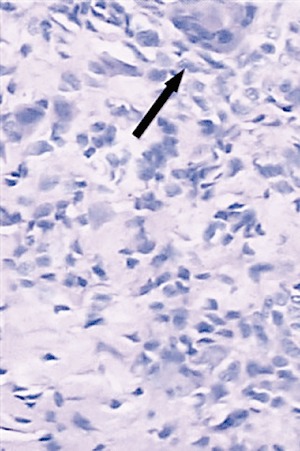

Figure 4.

Multinucleated giant cells (black arrow) can be seen on a hematoxylin and eosin stained specimen (×200).

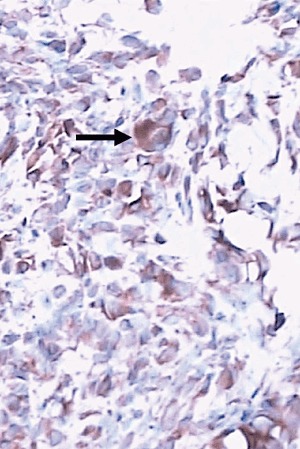

Figure 5.

Immunohistochemical staining for CD68 demonstrateing membrane positivity of the multinucleated cells (black arrow, ×200).

Case 2

A 34‐year‐old Chinese woman gave an 18 month history of a mass of increasing size, pain and plantar numbness as well as discomfort on weight bearing. She presented with a 1.0 cm × 1.0 cm, solitary, nonmobile, diffuse soft mass on the plantar aspect of the medial proximal phalanx of the right second toe. Previous history was normal with no medical problems or surgeries.

Plain radiography showed an opacity around the medial right second toe (Fig. 6) and fracture of the middle phalanx, this being revealed more distinctly on the plantar aspect by CT three‐dimensional reconstruction (Fig. 7). MRI revealed a lobulated soft tissue mass located in the middle of the second toe and extending from the dorsal extensor tendons laterally to encircle the flexor tendons (Fig. 8). Neurovascular structures abutted the mass on its medial aspect.

Figure 6.

Plain radiograph showing an opacity around the mid diaphysis of the right second toe and a low density shadow approximately the size of a pinhole (white arrow).

Figure 7.

Three‐dimensional reconstructive CT (plantar) showing an osteolytic area in the middle phalanx of right second toe. The osteolytic area limits in cortical without medullary erosion.

Figure 8.

(A) Sagittal plane MRI displaying a soft‐tissue tumor on the plantar aspect of the second toe with a characteristic low signal on T1weighted image. (B) Coronal plane MRI showing the soft‐tissue tumor separated by a pseudomembrane and bulging on both sides of the second toe.

The patient underwent an excision biopsy, revealing a soft mass measuring 1.0 cm × 1.0 cm × 0.5 cm. Because the extensor and flexor tendons were encircled by the mass, they had to be sacrificed. The medial neurovascular bundle was not dissected off the pseudocapsule. A subperiosteal dissection was then performed on the middle phalanx. The tumor invading the middle phalanx was found to have encroached only on cortical bone and had not reached the medullary space, so intralesional curettage was performed. The proximal interphalangeal joint was stable.

Histopathological examination showed a circumscribed mass consisting of cellular fibrous tissue with septa separating numerous fibroblast‐like cells, foam cells, hemosiderin macrophages and multinucleated giant cells. No evidence of malignancy was seen. A final diagnosis of GCTTS was made. The membranes of the multinucleated cells were positive for CD68.

Eighteen months postoperatively, no recurrence was detectable by clinical and radiographic examination. The patient had returned to normal activities with no functional impairment.

Discussion

Giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath is a slow growing, benign soft tissue tumor that accounts for 1.6% of all soft tissue tumors 15 . It has a peak presentation between the second and fourth decades of life, and no racialpredominance has been found 3 . This tumor most commonly involves the tendon sheath of small joints, such as the fingers, which are the site of 77% of reported tumors 16 . The foot and ankle is the second most common anatomical site reported in literatures 5 , 15 , 17 . In this study, we report two cases in which this tumor affected the second toe. Such a location may confuse the clinician because it is so rare. Surgeons should keep these two rare cases in mind when considering the differential diagnosis of such tumors.

The symptoms of GCTTS are nonspecific and can mimic those of any type of soft‐tissue mass. In our two cases, the presenting complaint was a slow‐growing, noticeable mass with additional symptoms such as pain, limitation of motion and joint swelling. Clinically, the differential diagnosis includes ganglion cyst, rheumatoid nodule, lipoma, synovial sarcoma, inclusion cyst, fibroma of the tendon sheath, and inflammation of the synovial sheath 15 . These conditions are easily distinguished histologically from GCTTS. However, GCTTS and PVNS share many characteristics histologically, including the presence of giant cells. The distinguishing feature is the formation of villonodular projections in PVNS, these being absent in GCTTS. MRI is recommended for preoperative diagnosis. In our two cases, MRI localized the mass but did not provide a diagnosis. Histopathology is the only definitive method of diagnosis.

Being a locally aggressive tumor, GCTTS has a high tendency to recur after removal. Recurrence rates range from 9% to 44% 13 , 14 . In order to reduce the risk of recurrence, complete remove of tumor is vital. Postoperative radiotherapy has been advocated by some researchers to reduce the recurrence rate, although there is no confirmed evidence that it achieves this. Few previously published studies have addressed the management of destruction or instability of a joint caused by tumor erosion or removal of a mass. In Case 1 in this study, the proximal interphalangeal joint was unstable after removal of the tumor mass, and the joint was fixed with a Kirschner wire. Tumor in a toe may cause toe deformity and loss of the physiological angle, depending on the site and size of tumor. If it causes hallux valgus, continuous pain on walking will occur, as reported by Kuo et al. 18 They described a case with continuous pain on walking due to hallux valgus deformity caused by GCTTS. Excision of the tumor and correction of the hallux valgus deformity were performed on this patient, who was able to walk freely without any discomfort after discharge from hospital and expressed satisfaction with the result. On the basis of our two cases and relevant published articles, we recommend that GCTTS treatment include not only complete local excision, but also reconstruction of the foot in order to restore the function of the foot. A specific surgical plan should be formulated depending on the particular problems caused by the mass or erosion.

Disclosure

The authors declare that there are no competing interests in this study.

References

- 1. Jaffe HL, Lichtenstein L, Suro CJ. Pigmented villonodular synovitis, bursitis and tenosynovitis. Arch Pathol, 1941, 31: 731–765. [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Keefe RJ, O'Donnell RJ, Temple HT, et al Giant cell tumor of bone in the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int, 1995, 16: 617–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Darwish FM, Haddad WH. Giant cell tumour of tendon sheath: experience with 52 cases. Singapore Med J, 2008, 49: 879–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Abdullah A, Abdullah S, Haflah NH, et al Giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath in the knee of an 11‐year‐old girl. J Chin Med Assoc, 2010, 73: 47–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gibbons CL, Khwaja HA, Cole AS, et al Giant‐cell tumour of the tendon sheath in the foot and ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 2002, 84: 1000–1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. LaRussa LR, Labs K, Schmidt RG, et al Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath. J Foot Ankle Surg, 1995, 34: 541–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Llauger J, Palmer J, Rosón N, et al Pigmented villonodular synovitis and giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath: radiologic and pathologic features. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 1999, 172: 1087–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Savage RC, Mustafa EB. Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath (localized nodular tenosynovitis). Ann Plast Surg, 1984, 13: 205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thaxton L, AbuRahma AF, Chang HH, et al Localized giant cell tumor of tendon sheath of upper back. Surgery, 1995, 118: 901–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Villani C, Tucci G, Di Mille M, et al Extra‐articular localized nodular synovitis (giant cell tumor of tendon sheath origin) attached to the subtalar joint. Foot Ankle Int, 1996, 17: 413–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bruns J, Yazigee O, Habermann CR. Pigmented villo‐nodular synovitis and teno‐synovial giant‐cell tumors. Z Orthop Unfall, 2008, 146: 663–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Reilly KE, Stern PJ, Dale JA. Recurrent giant cell tumors of the tendon sheath. J Hand Surg Am, 1999, 24: 1298–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leung PC. Tumours of hand. Hand, 1981, 13: 169–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paez H, Vuletin JC, Soave RL, et al Pedal giant cell tumor of tendon sheath. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc, 1999, 89: 368–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lo EP, Ketterer D. Giant cell tumor of tendon sheath in the toe. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc, 2000, 90: 270–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jones FE, Soule EH, Coventry MB. Fibrous xanthoma of synovium (giant‐cell tumor of tendon sheath, pigmented nodular synovitis). A study of one hundred and eighteen cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 1969, 51: 76–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sheppard DG, Kim EE, Yasko AW, et al Giant‐cell tumor of the tendon sheath arising from the posterior cruciate ligament of the knee: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Imaging, 1998, 22: 428–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuo CL, Yang SW, Chou YJ, et al Giant cell tumor of the EDL tendon sheath: an unusual cause of hallux valgus. Foot Ankle Int, 2008, 29: 534–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]