Introduction

Monteggia fracture‐dislocations are rare injuries. They were first described by Monteggia in 1814 as featuring a fracture of the proximal third of the shaft of the ulna and an anterior or posterior dislocation of the proximal epiphysis of the radius. In 1967, Bado published the most influential classification of Monteggia fracture‐dislocations, subdividing them into four different combinations of ulna fracture and radial head dislocation 1 . The incidence of Monteggia lesions is only 1 to 2% of all childhood forearm injuries, and even less in adults 2 . With respect to adult patients, good results can only be obtained by early diagnosis and established internal fixation protocols 3 .

Monteggia fracture‐dislocations associated with ipsilateral distal humeral fracture are extremely rare injuries in adults. There are only three papers reporting this kind of lesion, one describing two adults 4 and the other two each reporting one childhood case 5 , 6 . The present case is the third reporting a similar injury in a skeletally mature individual. Based on Bado's classification, the patient we present sustained a Bado type II Monteggia lesion which differed from the previous two cases. To our knowledge, this combination of injuries has not previously been described. A favorable outcome was achieved thanks to the early diagnosis, achievement of anatomic reduction and management with rigid internal fixation, as well as early functional exercise.

Case report

A 19‐year‐old college student was injured in a high‐velocity motor‐vehicle accident. She sustained an ipsilateral intercondylar distal humerus fracture (AO classification C1) and a Monteggia fracture‐dislocation (Bado type II) in the left forearm (Fig. 1), accompanied by an incomplete posterior interosseous nerve palsy. Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) was performed 3 days after admission to hospital. An extended posterior approach was used to address the fractures. For the ulnar fracture, a seven‐hole, 3.5‐mm limited‐contact dynamic compression plate was used to ensure a minimum of six cortices of fixation. A closed stable radial head reduction was then performed. A triceps sparing approach was chosen for the distal humeral fracture. Two 3.5‐mm reconstruction plates were used for the distal humeral fracture and one lag screw for the intercondylar extension. The two plates were oriented at 90° to each other, with the lateral plate lying on the posterior surface of the humerus and the medial plate lying at 90° to this. The radial nerve was not explored because the incomplete nerve palsy was thought to be caused by the dislocated radial head; the nerve function could therefore be expected to recover gradually after reduction of the radial head.

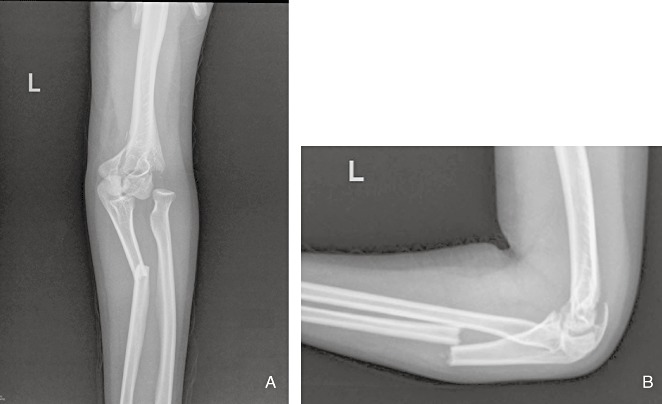

Figure 1.

Preoperative (A) anteroposterior (B) and lateral radiographs demonstrating posterolateral dislocation of the radial head and proximal one third diaphysis fracture of the ulna (type II Monteggia lesion) combined with intercondylar distal humeral fracture (type C1).

The postoperative period was uneventful. The elbow was immobilized with a long arm splint for 7 days, after which active exercise was started. At 6 week follow‐up, the patient did not complain of any symptoms of posterior interosseous nerve palsy. On evaluation thirteen months postoperatively, the radiographs demonstrated bony healing both in the ulna and the distal humerus, and correct position of the radial head was well maintained (Fig. 2). Implant removal was performed according to the patient's wishes (Fig. 3). At a 2 year follow‐up, the patient had a full extension, flexion to 130°, supination to 90°, and pronation to 80° (Fig. 4). Based on the Broberg and Morrey scale 7 , the end result was excellent.

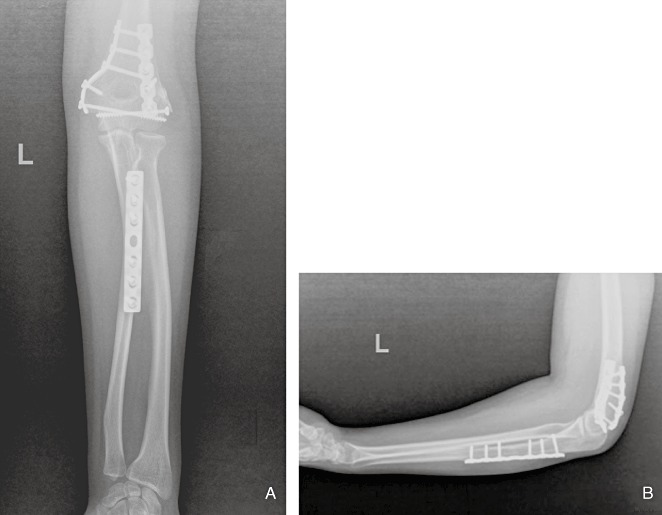

Figure 2.

(A) Anteroposterior and (B) lateral radiographs showing a good and stable healing of the distal humerus and ulnar diaphysis, as well as anatomical reduction of the radial head 13 months after surgery.

Figure 3.

Radiographs after removal of implants showing (A,B) anatomical reduction and (C,D) bony healing of distal humeral and ulna shaft fractures.

Figure 4.

Functional examination at 2 years follow‐up shows almost full range of (A) extension and (B) flexion of the elbow, and (C) supination and (D) pronation of the forearm.

Discussion

Many authors have published reports on the treatment of distal humeral fractures occurring in combination with Monteggia fracture‐dislocation. However, only a few have described the treatment of ipsilateral intercondylar distal humeral fracture and Monteggia fracture‐dislocation. There have been only three articles reporting four cases of this kind of injury so far. Two cases occurred in skeletally immature bone. Arazi et al. reported a thirteen year old girl who sustained an ipsilateral distal humeral, Monteggia and undisplaced distal radial fractures after a fall 5 . An ORIF was performed for the distal humeral and ulnar fractures. Closed reduction was performed on the radial head. A cast was used for six weeks after surgery. At a one‐year follow‐up, the girl had a full range of elbow and forearm movement. Wiley and Galey mentioned one case of a concomitant ipsilateral supracondylar humeral fracture in a series of Monteggia fracture‐dislocations in children 6 . The authors did not describe this particular case in detail.

Beredjiklian et al. reported two adult patients with AO type C1 distal humeral fractures associated with ipsilateral anterior Monteggia fracture‐dislocations 4 . ORIF was performed for the distal humeral and ulnar fractures in both cases. The final results were satisfactory despite flexion contracture in both cases.

In this report a nineteen‐year‐old female patient with AO type C1 distal humeral fracture associated with an ipsilateral posterior Monteggia fracture‐dislocation is presented. Although it was also the result of high‐energy motor‐vehicle accident, the mechanism of the injury probably involved a combination of elbow flexion and axial loading, which is different from that of previously reported cases. The patient also had incomplete posterior interosseous nerve palsy. We did not explore the radial nerve during surgery. Full recovery of the nerve function was found on evaluation 6 weeks postoperatively. Chevron osteotomy was not performed for the distal humeral fracture because of the proximal one‐third ulnar fracture. A lag screw rather than a positional cortical screw was used for the intercondylar extension of the distal humeral fracture, because compression of the two intra‐articular blocks can best be achieved with a lag screw. Although rigid internal fixation was obtained, a cast was used to facilitate wound healing and subsidence of swelling. The final result was rated as excellent according to the Broberg and Morrey scale.

In conclusion, Monteggia fracture‐dislocations associated with ipsilateral distal humeral fracture are extremely rare injuries in adults. A favorable outcome was achieved thanks to the early diagnosis, achievement of anatomic reduction and management with rigid internal fixation, as well as early functional exercise.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the “Ke‐Jiao‐Xing‐Wei‐Zhong‐Dian‐Yi‐Xue‐Ren‐Cai” Financial Assistance of Jiangsu Province (RC2007087). We gratefully acknowledge the excellent technical assistant of Gang Tang.

References

- 1. Bado JL. The Monteggia lesion. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1967, 50: 71–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reckling FW, Cordell LD. Unstable fracture‐dislocations of the forearm. The Monteggia and Galeazzi lesions. Arch Surg, 1968, 96: 999–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eathiraju S, Mudgal CS, Jupiter JB. Monteggia fracture‐dislocations. Hand Clin, 2007, 23: 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beredjiklian PK, Bozentka DJ, Ramsey ML. Ipsilateral intercondylar distal humerus fracture and Monteggia fracture‐dislocation in adults. J Orthop Trauma, 2002, 16: 438–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arazi M, Oğün TC, Kapicioğlu MI. The Monteggia lesion and ipsilateral supracondylar humerus and distal radius fractures. J Orthop Trauma, 1999, 13: 60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wiley JJ, Galey JP. Monteggia injuries in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br, 1985, 67: 728–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Broberg MA, Morrey BF. Results of treatment of fracture‐dislocations of the elbow. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1987, 216: 109–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]