Abstract

This study examines the change in matriculant sex, race, and ethnicity in US medical schools after the 2009 implementation of diversity standards from the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) meant to broaden diversity among qualified applicants.

To improve diversity in undergraduate medical education, in 2009, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) introduced 2 diversity accreditation standards mandating US allopathic medical schools to engage in systematic efforts to attract and retain students from diverse backgrounds and develop programs, such as pipeline and academic enrichment programs, to broaden diversity among qualified applicants.1 These standards characterized diversity broadly, including but not limited to sex, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. Because individual medical schools undergo accreditation review at least every 8 years, the LCME would have evaluated all schools for adherence by 2017. This observational study examined the change in US medical school matriculant sex, race, and ethnicity after the implementation of the LCME diversity accreditation standards.

Methods

This study was deemed exempt by the Yale University Institutional Review Board. We used Association of American Medical Colleges data that documented the number of matriculants by self-reported sex, race, and ethnicity, based on fixed categories consistent with the US Census, for all US LCME-accredited medical schools from 2002 through 2017. Historically black medical schools, schools in Puerto Rico, and schools not present throughout the entire study period were excluded (n = 30). School data were aggregated, and the percentages of female, black, Hispanic, Asian, and white medical students were calculated for each year. Native American and Hawaiian students were not included in the analysis because of small numbers.

We used interrupted time series analysis2 to evaluate the relationship between the implementation of the LCME diversity accreditation standards and the annual percentage of female, black, Hispanic, Asian, and white matriculants. Models were corrected to account for serially autocorrelated observations. A linear regression was performed assuming linear trends. Analyses were performed to account for a 1-, 2-, and 3-year postimplementation period. Because the length of the postimplementation period did not change significance for most results, we present results beginning in 2012, 3 years after the implementation of the diversity accreditation standards. Analyses were performed using Stata (StataCorp), version 14. Statistical significance was defined as a 2-sided P<.05.

Results

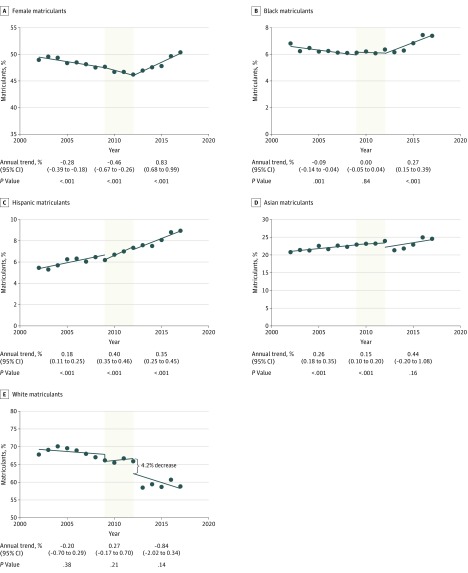

The final sample included 120 medical schools, with the number of matriculants increasing from 15 976 in 2002 to 18 853 in 2017. In 2002, 49.0% of matriculants identified as female, 6.8% as black, 5.4% as Hispanic, 20.8% as Asian, and 67.9% as white. By 2017, 50.4% of matriculants identified as female, 7.3% as black, 8.9% as Hispanic, 24.6% as Asian, and 58.9% as white.

From 2002 to 2009, before the implementation of the LCME diversity accreditation standards, the percentage of female and black matriculants decreased annually, while the percentage of Hispanic and Asian matriculants increased (Figure). There was no significant annual change in the percentage of white matriculants during that time.

Figure. Percentage of US Medical School Matriculants by Sex, Race, and Ethnicity, 2002-2017.

Time series of percentage of medical school matriculants by sex, race, and ethnicity. The 2002-2009 data represent the period before the introduction of the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) diversity accreditation standards. The shaded area from 2009 to 2012 is the LCME diversity standards implementation period. The lines represent the overall linear trend for the selected time period. 2012-2017 is the LCME diversity accreditation standards postimplementation period. Matriculant self-reported race or ethnicity represents data reported to the Association of American Medical Colleges either alone or in combination.

After the implementation of LCME diversity accreditation standards (2012-2017), the annual trend in the percentage of female and black matriculants reversed, increasing significantly relative to the trend from 2002 to 2009, while the annual trend in the percentage of Hispanic matriculants continued to increase (Figure). There was no significant difference in the annual trend in the percentage of Asian matriculants between 2012 to 2017 and 2002 to 2009. However, the overall percentage of white matriculants decreased by 4.2% in 2012 (95% CI, −0.44% to −8.0%; P = .03), the first postimplementation year. After 2012, there was no significant change in the annual trend of white matriculants.

Discussion

An association was observed between the implementation of the LCME diversity accreditation standards and increasing percentages of female, black, and Hispanic matriculants in US medical schools. Because this study was observational, causality cannot be demonstrated and there may be variables unaccounted for that were responsible for the change in matriculant demographics. Nevertheless, the authors are unaware of other national policies associated with medical school matriculant diversity during the study period. The number of pipeline programs and the use of holistic review by admissions committees may have increased after the implementation of the LCME diversity accreditation standards, which could account for some of the study’s findings. While the results are promising, disparities in physician workforce diversity persist.3 Future studies should evaluate changes in student demographics at individual schools. Institutions that successfully implemented programs to adhere to accreditation standards could serve as models for further improving physician diversity.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

Reference

- 1.Liaison Committee on Medical Education Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) Standards on Diversity. Washington, DC: American Association of Medical Colleges; 2009. https://health.usf.edu/~/media/Files/Medicine/MD%20Program/Diversity/LCMEStandardsonDiversity1.ashx?la=en. Accessed September 20, 2018.

- 2.Shadish W, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deville C, Hwang WT, Burgos R, Chapman CH, Both S, Thomas CR Jr. Diversity in graduate medical education in the United States by race, ethnicity, and sex, 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1706-1708. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.4324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]