Key Points

Question

In patients with distributive shock (a condition due to excessive vasodilation, most frequently from severe infection), is the addition of vasopressin to catecholamine vasopressors superior to catecholamine vasopressors alone for atrial fibrillation?

Findings

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of 23 trials that included 3088 patients with distributive shock, the addition of vasopressin to catecholamine vasopressors compared with catecholamine vasopressors alone was significantly associated with a lower risk of atrial fibrillation (relative risk, 0.77).

Meaning

Addition of vasopressin to catecholamines may offer a clinical advantage for prevention of atrial fibrillation.

Abstract

Importance

Vasopressin is an alternative to catecholamine vasopressors for patients with distributive shock—a condition due to excessive vasodilation, most frequently from severe infection. Blood pressure support with a noncatecholamine vasopressor may reduce stimulation of adrenergic receptors and decrease myocardial oxygen demand. Atrial fibrillation is common with catecholamines and is associated with adverse events, including mortality and increased length of stay (LOS).

Objectives

To determine whether treatment with vasopressin + catecholamine vasopressors compared with catecholamine vasopressors alone was associated with reductions in the risk of adverse events.

Data Sources

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL were searched from inception to February 2018. Experts were asked and meta-registries searched to identify ongoing trials.

Study Selection

Pairs of reviewers identified randomized clinical trials comparing vasopressin in combination with catecholamine vasopressors to catecholamines alone for patients with distributive shock.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two reviewers abstracted data independently. A random-effects model was used to combine data.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was atrial fibrillation. Other outcomes included mortality, requirement for renal replacement therapy (RRT), myocardial injury, ventricular arrhythmia, stroke, and LOS in the intensive care unit and hospital. Measures of association are reported as risk ratios (RRs) for clinical outcomes and mean differences for LOS.

Results

Twenty-three randomized clinical trials were identified (3088 patients; mean age, 61.1 years [14.2]; women, 45.3%). High-quality evidence supported a lower risk of atrial fibrillation associated with vasopressin treatment (RR, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.67 to 0.88]; risk difference [RD], −0.06 [95% CI, −0.13 to 0.01]). For mortality, the overall RR estimate was 0.89 (95% CI, 0.82 to 0.97; RD, −0.04 [95% CI, −0.07 to 0.00]); however, when limited to trials at low risk of bias, the RR estimate was 0.96 (95% CI, 0.84 to 1.11). The overall RR estimate for RRT was 0.74 (95% CI, 0.51 to 1.08; RD, −0.07 [95% CI, −0.12 to −0.01]). However, in an analysis limited to trials at low risk of bias, RR was 0.70 (95% CI, 0.53 to 0.92, P for interaction = .77). There were no significant differences in the pooled risks for other outcomes.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this systematic review and meta-analysis, the addition of vasopressin to catecholamine vasopressors compared with catecholamines alone was associated with a lower risk of atrial fibrillation. Findings for secondary outcomes varied.

This meta-analysis compares the effects of vasopressin with vs without catecholamine vasopressors on atrial fibrillation, mortality, stroke, and other adverse outcomes in patients with distributive shock.

Introduction

In distributive shock, widespread vasodilation leads to decreased systemic vascular resistances and mean arterial pressure (MAP).1 If not reversed, end-organ hypoperfusion results in significant morbidity; mortality rates reached 50% in observational studies conducted in 2013 and 2014.2,3 Sepsis is the most common cause of distributive shock. It can also occur after cardiovascular surgery, spinal cord injury, or arise as a consequence of anaphylaxis or prolonged hypoperfusion.1,4

Managing distributive shock involves treating the underlying cause, volume resuscitation, and infusing vasopressors to maintain a perfusing blood pressure.5,6 Clinicians frequently use catecholaminergic vasopressors (eg, norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, dobutamine). However, catecholamines have adverse effects including myocardial ischemia and arrhythmia,6,7,8 which may affect outcomes.9

Atrial fibrillation is a common adverse event in patients with distributive shock and is independently associated with morbidity, mortality, and increases in length of stay (LOS).10,11,12

Vasopressin, an endogenous peptide hormone, can also be used as a vasopressor. Patients with septic shock have relative vasopressin deficiency and exogenous administration of vasopressin raises blood pressure by increasing vascular tone.13 By reducing the requirement for catecholamines, it decreases the stimulation of arrhythmogenic myocardial β1-receptors and associated myocardial oxygen demand.7,14 This, among other mechanisms, may translate into a reduction in adverse events, including atrial fibrillation, injury to other organs, and death.7,15 The most recent Surviving Sepsis guidelines suggest adding vasopressin to norepinephrine to raise MAP to target, or adding vasopressin to decrease norepinephrine dosage (weak recommendations, moderate quality of evidence).5

The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the association between treatment with vasopressin in addition to catecholamine vasopressors on atrial fibrillation, morbidity, and mortality compared with catecholamines alone.

Methods

The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (2017:CRD42017059058). The conduct and reporting of the study follow the PRISMA guidelines.

Eligibility Criteria

Randomized clinical trials were included, irrespective of publication status, date of publication, risk of bias, outcomes published, or language. Trials were included if they enrolled adults with distributive shock, including septic shock, post–cardiovascular surgery vasoplegia, neurogenic shock, and anaphylaxis. Included studies had to compare the administration of vasopressin (or analogues [eg, terlipressin, selepressin]) with or without concomitant catecholaminergic vasopressors with the administration of catecholaminergic vasopressors alone, irrespective of dose, duration, or co-intervention.

The primary outcome was atrial fibrillation. Secondary outcomes were mortality, requirement for renal replacement therapy (RRT), myocardial injury, ventricular arrhythmia, stroke, and LOS in the intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital (eAppendices 4-5 in the Supplement). Acute kidney injury and digital ischemia were post hoc outcomes.

The outcomes were accepted as defined by study authors. For mortality, mortality at 28 to 30 days, at longest follow-up, and in-hospital were considered equivalent; ICU mortality was not pooled. Under digital ischemia, limb ischemia and peripheral ischemia or cyanosis were included. Myocardial infarction, myocardial ischemia, troponin rise, and acute coronary syndrome were pooled under myocardial injury. Ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation were pooled as ventricular arrhythmia. Cerebrovascular accident was combined with stroke.

Search Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, and CENTRAL were searched for keywords describing the condition, intervention, or comparator from inception to February 25, 2018 (eAppendices 1-3 in the Supplement). An information specialist reviewed the search strategies.

Trial registries were searched for ongoing and unpublished clinical trials via http://www.isrctn.com using the multiple database search option metaRegister of Controlled Trials and the World Health Organization trial registry. Authors hand-searched the conference proceedings for the scientific sessions of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, the Society of Critical Care Medicine, and the American Thoracic Society in the last 2 years. The references of eligible papers were screened and experts were consulted to identify additional trials.

Data Collection and Analysis

Two reviewers independently screened studies’ titles and abstracts for eligibility. Full papers of the potentially eligible studies were retrieved. The same 2 reviewers then independently screened full texts in duplicate and recorded the main reason for exclusion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Data Extraction and Management

Independently, 2 reviewers abstracted data on intervention and outcome. They also recorded study and patient characteristics including age, sex, type of shock, and concomitant conditions (eg, cirrhosis, malignancy). They compared results and resolved disagreements by discussion with a third party. Authors were contacted to clarify ambiguities and to request data on outcomes missing in primary reports.

Assessment of Risk of Bias

In duplicate, 2 review authors assessed risk of bias.16 In each trial, reviewers evaluated the following domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of patients and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, and selective reporting. The results were compared and disagreements resolved by discussion. Performance and detection bias were assessed separately. All open-label studies were classified as being at high risk of performance bias. A priori, the decision was made to classify open-label designs as “likely low risk of bias” for detection bias for mortality, stroke, and LOS in the absence of other concerns, but to judge “likely high risk of bias” for detection bias for atrial fibrillation, RRT, digital ischemia, myocardial injury, and ventricular arrhythmia. For analysis and presentation purposes, risk of bias was dichotomized as high (or likely high) or low (or likely low).

For subgroup analyses, the study-level risk of bias was assessed for each outcome. If a study was at risk of selection, performance, detection, or reporting bias for that outcome, it was categorized as high risk of bias. Additionally, studies at risk of attrition bias were categorized as high risk of bias for mortality.

Measures of Association With Treatment

The main reported standard association measure for clinical outcomes was risk ratios (RRs) and mean differences for LOS. Risk difference and absolute risk difference were also calculated for clinical outcomes. The absolute risk difference was obtained by applying the RRs with 95% CIs to the baseline risk in the control group. To permit meta-analysis, if a study reporting on LOS provided a median and a measure of dispersion, this was converted to mean and standard deviation assuming a normal distribution.17

Clinical and methodological heterogeneity were assessed based on study characteristics. Statistical heterogeneity was measured with the I2 statistic. An I2 statistic greater than 50% was considered as showing substantial heterogeneity.16

RevMan (Cochrane Collaboration), version 5.3, was used to combine data quantitatively when clinical heterogeneity was nonsubstantial. A random-effects model with Mantel-Haenszel weighting was used because several comparisons were expected to show heterogeneity. After recognizing that a substantial proportion of the weight for atrial fibrillation was contributed by a single study,18 we combined data for this outcome with a fixed-effect model in a sensitivity analysis. For trials in which patients crossed over to the other treatment, the analysis was according to their first assigned group (intention-to-treat principle). Two-sided P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

Subgroup and Sensitivity Analyses

Prespecified subgroup analyses were performed hypothesizing that patients with sepsis would derive greater benefit vs cardiovascular surgery. As a separate sensitivity analysis for RRT, the outcome definition was changed to acute kidney injury, as defined by study authors. P values for interaction between subgroups were tested.

Assessment of the Quality of the Evidence

The GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation) approach19 was used to grade the quality of evidence. GRADE appraises the confidence in estimates of effect by considering within-study risk of bias, directness of the evidence, heterogeneity of the data, precision of effect estimates, and risk of publication bias. Funnel plots of standard errors vs effect estimates were inspected for publication bias and small-study effects.

Results

Screening

The electronic search resulted in 1210 unique citations (Figure 1). After reference and full-text screening, 23 studies met eligibility criteria. Details on excluded and included studies and 3 potentially relevant ongoing studies are available (eAppendices 6-8 in the Supplement).

Figure 1. Flow of Study Selection for Trials Comparing Vasopressin + Catecholamines vs Catecholamines Alone for Patients With Distributive Shock.

Included Studies

The 23 studies that compared vasopressin in combination with catecholamines vs catecholamines alone included 3088 patients (mean age, 61.1 years [14.2]; women, 45.3%) (Table 1). Five trials were multicenter.30,33,37,39,40 Twenty-two studies included patients with septic shock.20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41 Two studies evaluated patients with post–cardiac surgery vasoplegia.18,28 Vasopressin was the intervention in 13 trials,18,23,24,27,28,29,30,33,34,35,36,37,39 whereas 9 studied terlipressin,20,21,22,25,26,32,35,38,41 1 studied selepressin,40 and 1 studied pituitrin (a mixture of vasopressin and oxytocin).31 One 3-group study compared vasopressin vs terlipressin vs norepinephrine alone.35 Five studies were published only as abstracts.18,21,27,36,38

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Randomized Clinical Trials Comparing Vasopressin + Catecholamines vs Catecholamines Alone in Patients With Distributive Shock.

| Source | Design | Setting | No. of Patients | Condition | Treatment Group(s) | Comparison Group(s) | Planned Follow-up | Risk of Bias for Atrial Fibrillation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdullah et al,20 2012 | Open label | Single center | 34 | Paracentesis-induced vasodilatory shock and end-stage liver disease | Terlipressin: 1 mg over 30 min, then continuous infusion of 2 μg/kg/min titrated up and weaned within 24 h | NE: 0.1 μg/kg/min titrated up and weaned within 24 h | 48 h | High |

| Acevedo et al,21 2009 | Open label | Single center | 24 | Septic shock and cirrhosis | Terlipressin: 1-2 mg over 4 h | Adrenergic drugs as needed | Hospital LOS | High |

| Albanese et al,22 2005 | Open label | Single center | 20 | Septic shock and 2 or more organ dysfunctions | Terlipressin: 1-mg bolus, then another 1-mg bolus if MAP <65 mm Hg | NE: 0.3 μg/kg, then increased by 0.3 μ/kg every 4 min until MAP between 65-75 mm Hg | Hospital LOS | High |

| Barzegar et al,23 2014 | Open label | Single center | 30 | Septic shock | Vasopressin: 0.03 U/min | NE as needed for MAP >65 mm Hg | 28 d | High |

| Capoletto et al,24 2017 | Double-blind | NA | 107 | Septic shock and cancer | Vasopressin: not described | NE: not described | 90 d | Low |

| Chen et al,25 2017 | Open label | Single center | 57 | Acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock | Terlipressin and NE: 0.01-0.04 U/min of terlipressin and NE as needed to maintain MAP between 65-75 mm Hg | NE: >1 μg/min | 28 d | High |

| Choudhury et al,26 2016 | Open label | Single center | 84 | Septic shock and cirrhosis | Terlipressin: 1.3-5.2 μg/min over 24 h | NE: 7.5-60 μg/min | 28 d | High |

| Clem et al,27 2016 | Open label | Single center | 82 | Septic shock | Vasopressin and NE: 0.05-0.5 μg/kg/min of NE and 0.04 U/min of vasopressin to maintain MAP between 65-75 mm Hg | NE: 0.05-0.5 μg/kg/min to maintain MAP between 65-75 mm Hg | 28 d | High |

| Dünser et al,28 2003 | Open label | Single center | 48 | Vasodilatory shock including septic shock, sepsis, and cardiotomy | Vasopressin: 4 U/h at a constant rate | NE: as needed for MAP >70 mm Hg, and additional vasopressin for NE requirements >2.26 μg/kg/min | ICU LOS | High |

| Fonseca Ruiz et al,29 2013 | Open label | Single center | 30 | Septic shock | Vasopressin and NE: NE + vasopressin at titrated doses of 0.01 U/min, then increased by 0.01 U/min every 10 min to achieve MAP >65 mm Hg or until maximum dose of 0.04 U/min | NE | 28 d | High |

| Gordon et al,30 2016 | Double-blind | Multicenter | 421 | Septic shock | Vasopressin: up to 0.06 U/min with target MAP between 65-75 mm Hg, or at physician’s discretion | NE: up to 12 μg/min with target MAP between 65-75 mm Hg, or at physician’s discretion | 28 d | Lowa |

| Hajjar et al,18 2017 | Double-blind | Single center | 330 | Vasoplegia after cardiac surgery | Vasopressin: 0.01-0.06 U/min with MAP >65 mm Hg | NE: 10-60 μg/min with MAP >65 mm Hg | 30 d | Lowa |

| Han et al,31 2012 | Open label | Single center | 139 | Septic shock | Pituitrin: 1.0-2.5 U/h | NE: 2-20 μg/kg/min | 28 d | High |

| Hua et al,32 2013 | Open label | Single center | 32 | Septic shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome | Terlipressin: 1.3 μg/kg/h | Dopamine: 20 μg/kg/min | 28 d | High |

| Lauzier et al,33 2006 | Open label | Multicenter | 23 | Septic shock | Vasopressin: 0.04-0.20 U/min | NE: 0.1-2.8 μg/kg/min | ICU LOS | High |

| Malay et al,34 1999 | Double-blind | Single center | 10 | Septic shock | Vasopressin: 0.04 U/min | Placebo | 24 h | Low |

| Morelli et al,35 2009b | Open label | Single center | 45 | Septic shock | Group 1: vasopressin: 0.03 U/min continuously over 48 h | NE as needed | ICU LOS | High |

| Group 2: terlipressin: 1.3 μg/kg/min continuously over 48 h | ||||||||

| Oliveira et al,36 2014 | Double-blind | Single center | 387 | Septic shock | Vasopressin: 0.01-0.03 U/min | NE: 0.05-2.0 μg/kg/min | 28 d | High |

| Patel et al,37 2002 | Double-blind | Multicenter | 24 | Septic shock | Vasopressin: 0.01-0.08 U/min | NE: 2-16 μg/min | 4 h | Low |

| Prakash et al,38 2017 | Open label | NS | 184 | Cirrhosis and sepsis | Terlipressin and NE: 2 mg/24 h fixed dose infusion of terlipressin and 3.75-30 μg/min of NE as needed to maintain MAP >65 mm Hg | NE: 7.5-60 μg/min | 30 d | High |

| Russell et al,39 2008 | Double-blind | Multicenter | 802 | Septic shock | Vasopressin: 0.01 U/min, then titrated up to 0.03 U/min with target MAP between 65-75 mm Hg, or at physician’s discretion | NE: 5 μg/min to 15 μg/min with target MAP between 65-75 mm Hg, or at physician’s discretion | 90 d | Low |

| Russell et al,40 2017 | Double blind | Multicenter | 53 | Septic shock | Selepressin: 1.25, 2.5, or 3.75 ng/kg/min until shock resolution or a maximum of 7 d | Placebo | 28 d | Lowa |

| Svoboda et al,41 2012 | Open label | Single center | 32 | Septic shock | Terlipressin: 4 mg over 24 h for 72 h | NE as needed | 28 d | High |

Abbreviations: ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; MAP, mean arterial pressure; NE, norepinephrine or noradrenaline; NS, not specified.

Trial judged to be at high risk of bias for mortality due to violation of the intention-to-treat principle.

Morelli et al, 2009,35 comprised 3 groups (vasopressin vs terlipressin vs norepinephrine). It was considered as 2 separate trials (vasopressin vs norepinephrine and terlipressin vs norepinephrine) in the comparison between vasopressin and vasopressin analogs. It was considered as a single trial (vasopressin or terlipressin vs norepinephrine) in all other comparisons.

Risk of Bias

Fifteen of 23 trials were not blinded (eAppendices 9-10 in the Supplement). Performance bias due to lack of blinding was judged to have an important effect on all outcomes; patients with distributive shock are critically ill and receiving many concomitant interventions that could be influenced by choice of concomitant vasopressor. Atrial fibrillation, myocardial injury, and digital ischemia are vulnerable to detection bias from differential capture and subjective interpretation; lack of blinding of clinicians and outcome assessors may influence these outcomes. The decision to start RRT could also be subjective. Other outcomes were judged to be at low risk of detection bias in the absence of blinding. Two studies were assessed to be at risk of selection bias due to inadequate randomization31,36; they did not describe their randomization process and had significant between-group imbalances. Nine studies (39%) reported the information necessary to make a definitive judgment for selection bias. Authors relied on imbalances between groups and overall methodological quality of the study to make this judgment. Attrition was found in 7 studies,18,25,30,31,36,40,41 and judged as having an effect on mortality (Table 2 and Figure 2A). Reporting bias was not detected. “Other bias” was judged to be present when studies were published as abstracts only. Prespecified sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of estimates to risk of bias if studies were dichotomized according to their risk of bias.

Table 2. Association of Vasopressin + Catecholamine Vasopressors vs Catecholamines Alone With Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Distributive Shock and Sensitivity Analyses.

| Group | No. With Events/Total No. of Patients | Risk Difference, % (95% CI)a | Relative Riska | Quality of Evidence | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vasopressin + Catecholamines | Catecholamines Alone | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | I2 % | |||

| All studies18,20,24,26,27,28,30,33,34,35,39,40,41 | 159/739 | 215/723 | −6 (−13 to 1) | 0.77 (0.67 to 0.88) | <.001 | 1 | High |

| Low risk of bias18,24,30,34,39,40 | 136/559 | 182/554 | −7 (−20 to 5) | 0.77 (0.68 to 0.88) | <.001 | 0 | |

| High risk of bias20,26,27,28,33,35,41 | 23/180 | 33/169 | −3 (−10 to 4) | 0.73 (0.40 to 1.34) | .31 | 36 | |

| Sepsis20,24,26,27,28,30,33,34,35,39,40,41,b | 60/580 | 84/563 | −3 (−7 to 1) | 0.76 (0.55 to 1.05) | .09 | 8 | |

| Cardiac surgery18,28,c | 99/159 | 131/160 | −19 (−29 to −10) | 0.77 (0.67 to 0.88) | <.001 | 0 | |

| Vasopressin18,24,27,28,30,33,34,35,39,b,c | 151/621 | 201/626 | −7 (−17 to 3) | 0.77 (0.68 to 0.88) | <.001 | 0 | |

| Vasopressin analogues20,26,35,40,41,c | 8/118 | 18/112 | −0.05 (−11 to 1) | 0.52 (0.18 to 1.51) | .23 | 28 | |

| Fixed-effect analysis18,20,24,26,27,28,30,33,34,35,39,40,41,b,c | 159/739 | 215/723 | −7 (−11 to −4) | 0.75 (0.65 to 0.86) | <.001 | 1 | |

Relative risk <1.0 and risk difference <0.0 favors vasopressin + catecholamines.

Dünser et al, 2003,28 included patients with both sepsis and post–cardiac surgery vasoplegia, but subgroup data were obtained for atrial fibrillation only. This study was excluded from other outcomes when sepsis and post–cardiac surgery vasoplegia were compared.

Morelli et al, 2009,35 comprised 3 groups (vasopressin vs terlipressin vs norepinephrine). It was considered as 2 separate trials (vasopressin vs norepinephrine and terlipressin vs norepinephrine) in the comparison between vasopressin and vasopressin analogs. It was considered as a single trial (vasopressin or terlipressin vs norepinephrine) in all other comparisons.

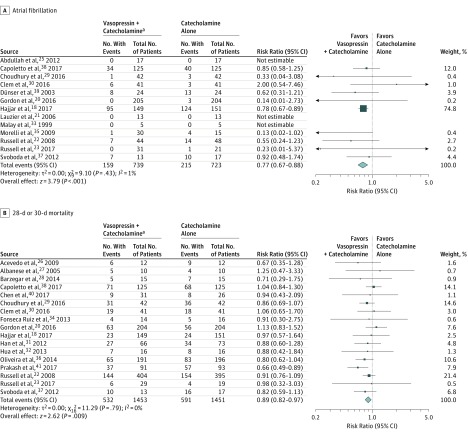

Figure 2. Relative Risks of All Trials Comparing Vasopressin + Catecholamines vs Catecholamines Alone for Patients With Distributive Shock.

The relative risks were calculated using a random-effects model with Mantel-Haenszel weighting. The size of data markers indicates the weight of the study. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

aVasopressin (or analogue [ie, terlipressin, selepressin, or pituitrin]) + catecholamine vasopressors.

Primary Outcome

Atrial Fibrillation

Pooling data from 13 studies (4 studies with 0 events in either group, 1462 patients, 374 events) demonstrated a significant reduction in the risk of atrial fibrillation associated with the administration of vasopressin (RR, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.67 to 0.88], I2 = 1%; risk difference [RD], −0.06 [95% CI, −0.13 to 0.01]) (Figure 2A). Based on the GRADE framework, this was judged to be high-quality evidence (eAppendix 13 in the Supplement). This result was driven by the study by Hajjar et al,18 which carried 74.8% of the weight. In absolute terms, the absolute effect is that 68 fewer people per 1000 patients (95% CI, 36 to 98) will experience atrial fibrillation when vasopressin is added to catecholaminergic vasopressors. In a sensitivity analysis excluding the 7 studies at high risk of bias for lack of blinding of outcome assessors,20,26,27,28,33,35 the estimate of effect was unchanged (eAppendix 11 in the Supplement). In a second sensitivity analysis, patients with sepsis and post–cardiac surgery were considered separately. For the subgroup of post–cardiac surgery patients,18,28 the resultant RR estimate was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.67 to 0.88), not significantly different than in patients with sepsis (RR, 0.76 [95% CI, 0.55 to 1.05], P for interaction = .97) (Table 2). Even though the crude rate of atrial fibrillation in this post–cardiac surgery population (73%) was considerably higher than in the sepsis studies (13%), the relative effect estimate was similar in both groups.

Secondary Outcomes

Mortality

Mortality data were available from 17 studies (2904 patients, 1123 events) (Figure 2B). When pooled, the administration of vasopressin in addition to catecholamines was associated with a reduction in mortality (RR, 0.89 [95% CI, 0.82 to 0.97], P = .009, I2 = 0; RD, −0.04 [95% CI, −0.07 to 0.00]). In absolute terms, 45 lives (95% CI, 12 to 73) would be saved per 1000 patients treated with vasopressin. However, when limited to the 2 trials at low risk of bias (Table 3),24,39 the RR estimate was 0.96 (95% CI, 0.84 to 1.11).

Table 3. Binary Outcomes and Sensitivity Analyses for Vasopressin + Catecholamines vs Catecholamines Alone in Patients With Distributive Shock.

| Group | No. With Events/Total No. of Patients | Risk Difference % (95% CI)a | Relative Riska | Quality of Evidence (Reason for Judgment) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vasopressin + Catecholamines | Catecholamines Alone | Risk Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | I2 % | |||

| 28-d or 30-d Mortality | |||||||

| All studies18,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,36,38,39,40,41 | 532/1453 | 591/1451 | −4 (−7 to 0) | 0.89 (0.82 to 0.97) | .009 | 0 | Low (risk of bias) |

| Low risk of bias24,39 | 215/529 | 222/520 | −2 (−8 to 4) | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.11) | .6 | 0 | |

| High risk of bias18,21,22,23,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,36,38,40,41 | 317/924 | 369/931 | −4 (−8 to 0) | 0.86 (0.77 to 0.95) | .004 | 0 | |

| 28-d or 30-d or ICU mortality18,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,38,39,40,41,b,c | 567/1525 | 623/1505 | −4 (−7 to −1) | 0.89 (0.83 to 0.97) | .006 | 0 | |

| Full text only18,22,23,25,26,29,30,31,32,39,40,41,d | 334/993 | 356/984 | −2 (−6 to 2) | 0.91 (0.82 to 1.01) | .09 | 0 | |

| Vasopressin23,24,27,29,30,36,39,41,b | 404/1156 | 431/1160 | −2 (−6 to 2) | 0.94 (0.85 to 1.04) | .21 | 0 | |

| Vasopressin analogues21,22,25,26,31,32,38,40,41,b | 128/297 | 160/291 | −10 (−18 to −3) | 0.81 (0.70 to 0.94) | .005 | 0 | |

| Sepsis21,22,23,24,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,36,38,39,40,41 | 509/1304 | 567/1300 | −4 (−8 to −1) | 0.89 (0.82 to 0.97) | .008 | 0 | |

| Cardiac surgery18 | 23/149 | 24/151 | −0 (−9 to 8) | 0.97 (0.57 to 1.64) | .91 | NA | |

| Requirement for Renal Replacement Therapy | |||||||

| All studies23,24,28,30,33,35,b,e | 97/412 | 125/393 | −7 (−12 to −1) | 0.74 (0.51 to 1.08) | .12 | 70 | Moderate (imprecision) |

| Low risk of bias24,30 | 62/330 | 89/329 | −7 (−13 to −2) | 0.70 (0.53 to 0.92) | .01 | 0 | |

| High risk of bias23,28,33,35,b,c | 35/82 | 36/64 | −5 (−16 to 7) | 0.77 (0.42 to 1.43) | .41 | 67 | |

| AKI as outcome18,21,24,28,30,b | 154/515 | 204/516 | −8 (−21 to 6) | 0.73 (0.46 to 1.17) | .19 | 91 | |

| Vasopressin23,24,28,30,33,35,b,e | 93/397 | 125/393 | −6 (−11 to −1) | 0.76 (0.53 to 1.10) | .15 | 68 | |

| Vasopressin analogues35,b,e | 4/15 | 8/15 | −27 (−60 to 7) | 0.50 (0.19 to 1.31) | .16 | NA | |

| Digital Ischemia | |||||||

| All studies18,23,24,26,29,30,39,40,41 | 41/990 | 17/973 | 2 (−1 to 4) | 2.38 (1.37 to 4.12) | .002 | 0 | Moderate (post hoc outcome) |

| Low risk of bias18,24,30,39,40 | 23/906 | 9/883 | 1 (−1 to 3) | 2.45 (1.10 to 5.43) | .03 | 0 | |

| High risk of bias23,26,29,41 | 18/84 | 8/90 | 10 (0 to 19) | 2.31 (1.08 to 4.94) | .03 | 0 | |

| Defined as digital ischemia18,23,29,30,33,39,40,f | 25/810 | 8/789 | 2 (0 to 3) | 2.73 (1.27 to 5.87) | .01 | 0 | |

| Vasopressin18,23,24,29,30,33,39,b | 24/904 | 10/893 | 1 (−1 to 3) | 2.35 (1.10 to 5.05) | .03 | 0 | |

| Vasopressin analogues26,40,41,b | 17/86 | 7/80 | 10 (−4 to 25) | 2.40 (1.09 to 5.31) | .03 | 0 | |

| Myocardial Injury | |||||||

| All studies18,20,24,28,30,33,34,37,39,40,41,b | 62/991 | 71/966 | 0 (−2 to 2) | 0.86 (0.63 to 1.17) | .34 | 0 | Low (indirectness, imprecision) |

| Low risk of bias18,24,30,34,37,39,40 | 61/924 | 66/899 | 1 (−1 to 3) | 0.89 (0.64 to 1.25) | .52 | 4 | |

| High risk of bias20,28,33,41,b | 1/67 | 5/67 | −5 (−12 to 3) | 0.37 (0.07 to 1.95) | .24 | 0 | |

| Sepsis20,24,28,30,33,34,37,39,40,41,b | 51/818 | 51/791 | 1 (−1 to 2) | 0.94 (0.67 to 1.32) | .71 | 0 | |

| Cardiac surgery18 | 11/149 | 17/151 | −4 (−10 to 3) | 0.66 (0.32 to 1.35) | .25 | NA | |

| Vasopressin18,24,28,30,33,34,37,39,b | 61/930 | 70/912 | 0 (−3 to 2) | 0.87 (0.61 to 1.23) | .42 | 6 | |

| Vasopressin analogues20,40,41,b | 1/61 | 1/54 | 1 (−6 to 7) | 0.91 (0.10 to 8.33) | .93 | 0 | |

| Ventricular Arrhythmia | |||||||

| All studies18,20,24,26,27,33,34,37,41 | 39/418 | 48/419 | 0 (−2 to 1) | 0.93 (0.73 to 1.19) | .55 | 0 | Low (indirectness, imprecision) |

| Low risk of bias18,34,37 | 27/167 | 32/167 | −2 (−10 to 5) | 0.86 (0.54 to 1.35) | .50 | NA | |

| High risk of bias20,24,26,27,33,41 | 12/251 | 16/252 | 0 (−1 to 1) | 0.96 (0.72 to 1.28) | .78 | 0 | |

| Vasopressin18,24,27,33,34,37,b | 28/346 | 32/343 | 0 (−1 to 2) | 0.88 (0.56 to 1.38) | .57 | 0 | |

| Vasopressin analogues20,26,41,b | 11/72 | 16/76 | −2 (−7 to 3) | 0.95 (0.71 to 1.27) | .73 | 0 | |

| Stroke | |||||||

| All studies18,24,39,41 | 11/683 | 6/675 | 1 (−2 to 4) | 1.61 (0.53 to 4.95) | .40 | 7 | Moderate (imprecision) |

| Low risk of bias18,24,39 | 11/670 | 6/658 | 1 (−2 to 4) | 1.61 (0.53 to 4.95) | .40 | 7 | |

| High risk of bias41 | 0/13 | 0/17 | 0 (−12 to 12) | NA | NA | NA | |

| Vasopressin18,24,39,b | 11/670 | 6/658 | 1 (−2 to 4) | 1.61 (0.53 to 4.95) | .40 | 7 | |

| Vasopressin analogues41,b | 0/13 | 0/17 | 0 (−12 to 12) | NA | NA | NA | |

Abbreviation: AKI, acute kidney injury.

Relative risk <1.0 and risk difference <0.0 favors vasopressin + catecholamines.

Dünser et al, 2003,28 included patients with both sepsis and post–cardiac surgery vasoplegia, but subgroup data were obtained for atrial fibrillation only. This study was excluded from other outcomes when sepsis and post–cardiac surgery vasoplegia were compared.

Added 4 studies that reported on ICU mortality.

“Full text only” refers to studies not published only as abstracts.

Morelli et al, 2009,35 comprised 3 groups (vasopressin vs terlipressin vs norepinephrine). It was considered as 2 separate trials (vasopressin vs norepinephrine and terlipressin vs norepinephrine) in the comparison between vasopressin and vasopressin analogs. It was considered as a single trial (vasopressin or terlipressin vs norepinephrine) in all other comparisons.

Includes only studies in which the authors described the outcome as digital ischemia. Peripheral cyanosis and limb ischemia were excluded.

Requirement for RRT and Acute Kidney Injury

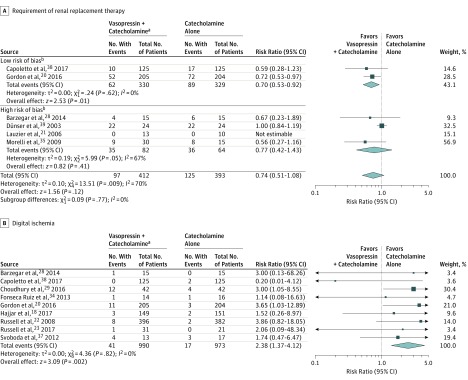

Six trials with a total of 805 patients (222 events) reported on RRT (Figure 3A). When combined, vasopressin was associated with a reduced risk for RRT, but the pooled estimate did not reach statistical significance and showed substantial heterogeneity (RR, 0.74 [95% CI, 0.51 to 1.08], I2 = 70%; RD, −0.07 [95% CI, −0.12 to −0.01]; moderate-quality evidence). However, when the analysis was limited to the 2 trials at low risk of bias,24,30 the point estimate was similar, but vasopressin was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of RRT without evidence of heterogeneity (RR, 0.70 [95% CI, 0.53 to 0.92], I2 = 0%, P for interaction = .77).

Figure 3. Relative Risks of All Trials Comparing Vasopressin + Catecholamines vs Catecholamines Alone for Patients With Distributive Shock.

The relative risks were calculated using a random-effects model with Mantel-Haenszel weighting. The size of data markers indicates the weight of the study. Error bars indicate 95% CIs.

aVasopressin (or analogue [ie, terlipressin, selepressin, or pituitrin]) + catecholamine vasopressors.

bRisk of bias categories for requirement for renal replacement therapy are the same as those for atrial fibrillation, as summarized in Table 1.

Myocardial Injury

Eleven studies (1957 patients, 133 events) reported on myocardial injury; 2 trials had event rates of 0 in both groups. There was no significant difference in the risk of myocardial injury with vasopressin (RR, 0.86 [95% CI, 0.63 to 1.17], I2 = 0%; RD, 0.00 [95% CI, −0.02 to 0.02]; low-quality evidence). After excluding studies at high risk of bias from open-label design,20,28,33,41 the estimate did not change significantly. Because surrogates were reported for myocardial injury (eg, altered ST segments), indirectness was rated as serious.

Ventricular Arrhythmia, Stroke, and Length of Stay

When 9 studies reporting on ventricular arrhythmia were pooled (837 patients, 87 events), the risk was not significantly different with vasopressin (RR, 0.93 [95% CI, 0.73 to 1.19], I2 = 0%; RD, 0.00 [95% CI, −0.02 to 0.01]; low-quality evidence). There was no significant difference when pooling data from 4 studies (1358 patients, 17 events) reporting on stroke (RR, 1.61 [95% CI, 0.53 to 4.95], I2 = 7%; RD, 0.01 [95% CI, −0.02 to 0.04]; moderate-quality evidence). LOS data were reported exclusively as medians with interquartile range and were transformed to estimate mean LOS with standard deviation. Hospital LOS was not significantly associated with vasopressin (8 studies, 1939 patients; mean difference, −1.14 days [95% CI, −3.60 to 1.32], I2=75%; low-quality evidence) (Table 4). Similarly, ICU LOS was not significantly associated with vasopressin (mean difference, −0.40 days [95% CI, −1.05 to 0.25], I2= 24%; moderate-quality evidence) when 11 studies were combined (2156 patients).

Table 4. Continuous Outcomes and Sensitivity Analyses for Vasopressin + Catecholamines vs Catecholamines Alone in Patients With Distributive Shock.

| Group | Mean Length of Stay in Days (SD)a | Mean Difference (95% CI), db | P Value | I2 % | Quality of Evidence (Reason for Judgment) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vasopressin + Catecholamines | Catecholamines Alone | |||||

| Hospital Length of Stay | ||||||

| All studies18,20,22,29,32,34,38,40 | 21.3 (23.0) | 22.6 (22.9) | −1.14 (−3.60 to 1.32) | .36 | 75 | Low (imprecision, inconsistency) |

| Low risk of bias18,24,30,39 | 22.0 (24.1) | 23.3 (23.8) | −1.83 (−4.47 to 0.81) | .17 | 69 | |

| High risk of bias29,32,34,40 | 15.7 (8.6) | 16.6 (11.1) | −0.45 (−4.40 to 3.50) | .82 | 62 | |

| Vasopressin18,24,29,30,39,c | 21.8 (24.0) | 23.4 (23.7) | −2.33 (−5.05 to 0.40) | .09 | 67 | |

| Vasopressin analogs29,32,40,c | 16.1 (7.7) | 14.9 (8.5) | 1.03 (−1.48 to 3.53) | .42 | 22 | |

| Intensive Care Unit Length of Stay | ||||||

| All studies18,20,22,28,29,31,32,35,38,39 | 11.1 (12.2) | 11.6 (13.4) | −0.40 (−1.05 to 0.25) | .23 | 24 | Moderate (imprecision) |

| Low risk of bias18,24,30,39 | 11.2 (12.7) | 12.2 (14.1) | −0.54 (−1.33 to 0.25) | .18 | 34 | |

| High risk of bias28,29,31,32,35,39,40 | 10.4 (10.2) | 9.4 (8.5) | −0.12 (−1.37 to 1.13) | .85 | 22 | |

| Vasopressin18,23,24,28,30,35,39,c | 11.8 (13.0) | 12.4 (14.0) | −0.24 (−1.27 to 0.79) | .65 | 44 | |

| Vasopressin analogues29,31,32,35,40,c | 7.9 (7.0) | 7.9 (7.0) | −0.38 (−1.33 to 0.58) | .44 | 0 | |

Mean length of stay was weighted by the number of patients.

Mean difference <0.0 favors vasopressin + catecholamines.

Morelli et al, 2009,35 comprised 3 groups (vasopressin vs terlipressin vs norepinephrine). It was considered as 2 separate trials (vasopressin vs norepinephrine and terlipressin vs norepinephrine) in the comparison between vasopressin and vasopressin analogs. It was considered as a single trial (vasopressin or terlipressin vs norepinephrine) in all other comparisons.

Post Hoc Outcomes

Digital Ischemia

When 9 studies (1963 patients, 58 events) were pooled (Figure 3B), vasopressin in addition to catecholamines was associated with a significant increase in digital ischemia (RR, 2.38 [95% CI, 1.37 to 4.12], I2 = 0; RD, 0.02 [95% CI, −0.01 to 0.04]; moderate-quality evidence). In absolute terms, this means 24 more occurrences (95% CI, 6 to 55) of digital ischemia per 1000 patients treated with vasopressin. When the 4 studies at high risk of bias were excluded,23,26,29,41 the resultant estimate was not significantly different. Definitions varied for this outcome; however, when the analysis was limited to the 6 studies that specifically described “digital ischemia,”18,23,29,30,39,40 the resultant estimate did not change significantly. Thus, evidence was not downgraded for indirectness but, because it was a post hoc outcome, it was downgraded for risk of bias.

Acute Kidney Injury

In a sensitivity analysis, the treatment effect for RRT was consistent, but not statistically significant when the definition was modified to acute kidney injury (5 trials; RR, 0.73 [95% CI, 0.46 to 1.17], I2 = 91%).

Publication Bias

The assessment of publication bias was limited by small numbers of studies for most outcomes (eAppendix 12 in the Supplement). Visual inspection did not lead to concerns about publication bias.

Discussion

In this systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials, the administration of vasopressin in addition to catecholamine vasopressors in patients with distributive shock was associated with a significant reduction in the risk of atrial fibrillation when compared with catecholamines alone (high-quality evidence). Findings for other outcomes were not consistent. Although when all studies were combined the risk of mortality was lower with the addition of vasopressin, a sensitivity analysis limited to low risk of bias trials yielded a relative risk much closer to 1 and was not statistically significant.

To our knowledge, this systematic review is the first on the topic to include atrial fibrillation as an outcome. Prior reviews assessed arrhythmia,42,43 but this outcome has limited utility due to the variety of conditions that could be found under this heading. The reduction in atrial fibrillation associated with vasopressin was consistent across 2 subtypes of distributive shock and in sensitivity analyses restricted to studies at low risk of bias.

Vasopressin may have contributed to a reduction of atrial fibrillation by sparing the adrenergic stimulation provided by catecholaminergic vasopressors.6,7,8,14 This could have manifested in fewer patients developing atrial fibrillation or may have caused atrial fibrillation to be shorter in duration and lower in rate and, in consequence, less likely to be detected.

The approach to monitoring and ascertainment of atrial fibrillation in patients who are acutely ill affects the detection of this outcome.44 This limitation would need to be addressed to more precisely estimate event rates in this population and their association with vasopressin treatment. The clinical significance of atrial fibrillation in this population is not fully understood.44 Where atrial fibrillation in patients who are critically ill has been associated with worse outcomes, including death, causality has not been proven and the consequences on long-term prognosis in survivors are unknown.10,11,44

This review is one of few reviews to directly compare vasopressin + catecholamines against the current standard of care—catecholamines alone. Two systematic reviews with network meta-analyses found no difference in mortality in any comparison, including between vasopressin or terlipressin and norepinephrine.42,43 Another systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that treatment with noncatecholaminergic agents (including vasopressin and methylene blue) improved survival (RR, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.79 to 0.98]) in patients experiencing or “at risk” for distributive shock.45 In another systematic review and meta-analysis, mortality was significantly lower in patients with septic shock treated with vasopressin or terlipressin compared with norepinephrine (RR, 0.87 [95% CI, 0.78 to 0.97]).46 However, that review included 4 substudies of the Vasopressin and Septic Shock Trial (VASST) in the meta-analysis of mortality and did not assess evidence using GRADE.19,39,47

The theoretical basis for vasopressin administration stems from research identifying relative vasopressin deficiency in patients with distributive shock.13 Vasopressin administration could lower mortality by decreasing the need for catecholaminergic drugs and reducing their adverse effects including arrhythmia, preferentially perfusing the brain and renal vascular bed—the latter leading to reductions in acute kidney injury—and decreasing activation of both the renin-aldosterone-angiotensin system and neurohormonal processes, inhibiting proinflammatory cytokines, improving calcium handling, and potentiating endogenous glucocorticoids.47,48,49,50

For clinicians aiming for MAP, maintaining adequate blood flow while mitigating the risk of excessive vasoconstriction (the likely mechanism of digital ischemia) is also important. An understanding of the clinical effect of these events (ie, did they simply precipitate drug discontinuation or did they lead to permanent disability?) would be needed to evaluate trade-off against a decrease in mortality.

This systematic review also evaluated requirement for RRT. The significant reduction in need for RRT with vasopressin was limited to the pooled estimate for low risk of bias studies. Renal protection related to reduced activation of the renin-aldosterone-angiotensin system is one of the hypothesized benefits of vasopressin in distributive shock; creatinine clearance has been shown to improve when vasopressin was started early after the onset of distributive shock.33

This review included data from the relatively large and recently published Vasopressin vs Norepinephrine in Patients with Vasoplegic Shock after Cardiac Surgery (VANCS) and Effect of Early Vasopressin vs Norepinephrine on Kidney Failure in Patients With Septic Shock (VANISH) trials (751 patients total).18,30 Combining subtypes of distributive shock and considering vasopressin analogs allowed the inclusion of a larger number of studies. Bias in the review process was reduced by searching multiple databases without language restriction. Significant attempts were made to obtain clarification of published data and access to unpublished data.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, subgroup analyses were restricted by the study-level nature of the data. Second, the quality of reporting for many studies was not sufficient to permit definitive judgments about risk of bias in all domains. Third, there are likely differences in the way vasopressors were initiated, titrated, and weaned between studies and approaches were infrequently described in detail. However, the general approach seemed to be to up-titrate vasopressin until the maximum dose or target MAP was reached and then to add or wean norepinephrine as needed to reach the target MAP.

Conclusions

In this meta-analysis, the addition of vasopressin to catecholamine vasopressors compared with catecholamines alone was associated with a lower risk of atrial fibrillation. However, findings for secondary outcomes varied.

eAppendix 1. MEDLINE Search Strategy

eAppendix 2. EMBASE Search Strategy

eAppendix 3. Cochrane CENTRAL Search Strategy

eAppendix 4. Basis for Outcome Selection

eAppendix 5. Outcome Importance for Choice of Vasopressor in Patients With Vasodilatory Shock

eAppendix 6. Characteristics of Included Studies

eAppendix 7. Characteristics of Important Excluded Studies

eAppendix 8. Characteristics of Ongoing Studies

eAppendix 9. Risk of Bias Graphs: Review Authors’ Judgments About Each Risk of Bias Item Presented as Percentages Across All 23 Randomized Trials

eAppendix 10. Risk of Bias Summary: Review Authors’ Judgments About Each Risk of Bias Item for Each Included Study

eAppendix 11. Forest Plots for All Outcomes, Including Sensitivity Analyses

eAppendix 12. Funnel Plots

eAppendix 13. Reported lengths of stay in primary studies and transformation of median and interquartile range to mean and standarddeviation

eAppendix 14. Summary of Findings Table

eReferences.

References

- 1.Landry DW, Oliver JA. The pathogenesis of vasodilatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(8):588-595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Machado FR, Cavalcanti AB, Bozza FA, et al. ; SPREAD Investigators; Latin American Sepsis Institute Network . The epidemiology of sepsis in Brazilian intensive care units (the Sepsis Prevalence Assessment Database, SPREAD): an observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(11):1180-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.SepNet Critical Care Trials Group Incidence of severe sepsis and septic shock in German intensive care units: the prospective, multicentre INSEP study. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(12):1980-1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gkisioti S, Mentzelopoulos SD. Vasogenic shock physiology. Open Access Emerg Med. 2011;3:1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):486-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vincent JL, De Backer D. Circulatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1726-1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dünser MW, Hasibeder WR. Sympathetic overstimulation during critical illness: adverse effects of adrenergic stress. J Intensive Care Med. 2009;24(5):293-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmittinger CA, Torgersen C, Luckner G, Schröder DC, Lorenz I, Dünser MW. Adverse cardiac events during catecholamine vasopressor therapy: a prospective observational study. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(6):950-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy B, Collin S, Sennoun N, et al. Vascular hyporesponsiveness to vasopressors in septic shock: from bench to bedside. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(12):2019-2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein Klouwenberg PM, Frencken JF, Kuipers S, et al. ; MARS Consortium . Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of new-onset atrial fibrillation in critically ill patients with sepsis: a cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(2):205-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moss TJ, Calland JF, Enfield KB, et al. New-onset atrial fibrillation in the critically ill. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(5):790-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walkey AJ, Wiener RS, Ghobrial JM, Curtis LH, Benjamin EJ. Incident stroke and mortality associated with new-onset atrial fibrillation in patients hospitalized with severe sepsis. JAMA. 2011;306(20):2248-2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landry DW, Levin HR, Gallant EM, et al. Vasopressin deficiency contributes to the vasodilation of septic shock. Circulation. 1997;95(5):1122-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dünser MW, Mayr AJ, Stallinger A, et al. Cardiac performance during vasopressin infusion in postcardiotomy shock. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(6):746-751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Backer D, Biston P, Devriendt J, et al. ; SOAP II Investigators . Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the treatment of shock. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(9):779-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. London, United Kingdom: Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14(1):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hajjar LA, Vincent JL, Barbosa Gomes Galas FR, et al. Vasopressin versus norepinephrine in patients with vasoplegic shock after cardiac surgery: the VANCS randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2017;126(1):85-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group . What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336(7651):995-998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdullah MH, Saleh SM, Morad WS. Terlipressin versus norepinephrine to counteract intraoperative paracentesis induced refractory hypotension in cirrhotic patients. Egyptian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2012;28(1):29-35. doi: 10.1016/j.egja.2011.10.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Acevedo JG, Fernandez J, Escorsell A, Mas A, Gines P, Arroyo V. Clinical efficacy and safety of terlipressin administration in cirrhotic patients with septic shock. J Hepatol. 2009;50:S73. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Albanèse J, Leone M, Delmas A, Martin C. Terlipressin or norepinephrine in hyperdynamic septic shock: a prospective, randomized study. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(9):1897-1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barzegar E, Ahmadi A, Mousavi S, Nouri M, Mojtahedzadeh M. The therapeutic role of vasopressin on improving lactate clearance during and after vasogenic shock: microcirculation, is it the black box? Acta Med Iran. 2016;54(1):15-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Capoletto C, Almeida J, Ferreira G, et al. Vasopressin versus norepinephrine for the management of septic shock in cancer patients (VANCS II). Presented at the Critical Care Conference: 37th International Symposium on Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine; March 21-24, 2017; Brussels, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z, Zhou P, Lu Y, Yang C. Comparison of effect of norepinephrine and terlipressin on patients with ARDS combined with septic shock: a prospective single-blind randomized controlled trial [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2017;29(2):111-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choudhury A, Kedarisetty CK, Vashishtha C, et al. A randomized trial comparing terlipressin and noradrenaline in patients with cirrhosis and septic shock. Liver Int. 2017;37(4):552-561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clem O, Painter J, Cullen J, et al. Norepinephrine and vasopressin vs norepinephrine alone for septic shock: randomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(12):413. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000510024.07609.07 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dünser MW, Mayr AJ, Ulmer H, et al. Arginine vasopressin in advanced vasodilatory shock: a prospective, randomized, controlled study. Circulation. 2003;107(18):2313-2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fonseca-Ruiz NJ, Cano ASL, Carmona DPO, et al. Uso de vasopresina en pacientes con choque séptico refractario a catecolaminas: estudio piloto. Acta Colombiana de Cuidado Intensivo. 2013;13(2):114-123. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gordon AC, Mason AJ, Thirunavukkarasu N, et al. ; VANISH Investigators . Effect of early vasopressin vs norepinephrine on kidney failure in patients with septic shock: the vanish randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(5):509-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Han XD, Sun H, Huang XY, et al. A clinical study of pituitrin versus norepinephrine in the treatment of patients with septic shock [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2012;24(1):33-37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hua F, Wang X, Zhu L. Terlipressin decreases vascular endothelial growth factor expression and improves oxygenation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome and shock. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(2):434-439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lauzier F, Lévy B, Lamarre P, Lesur O. Vasopressin or norepinephrine in early hyperdynamic septic shock: a randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(11):1782-1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Malay MB, Ashton RC Jr., Landry DW, Townsend RN. Low-dose vasopressin in the treatment of vasodilatory septic shock. J Trauma. 1999;47(4):699-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morelli A, Ertmer C, Rehberg S, et al. Continuous terlipressin versus vasopressin infusion in septic shock (TERLIVAP): a randomized, controlled pilot study. Crit Care. 2009;13(4):R130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oliveira S, Dessa F, Rocha C, Oliveira F. Early vasopressin application in shock study. Crit Care. 2014;18:S56. doi: 10.1186/cc13348 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel BM, Chittock DR, Russell JA, Walley KR. Beneficial effects of short-term vasopressin infusion during severe septic shock. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(3):576-582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prakash V, Choudhury AK, Sarin SK. To assess the efficacy of early introduction of a combination of low dose vasopressin analogue in addition to noradrenaline as a vasopressor in patients of cirrhosis with septic shock. Hepatology. 2017;66(suppl 1):138A. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Russell JA, Walley KR, Singer J, et al. ; VASST Investigators . Vasopressin versus norepinephrine infusion in patients with septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(9):877-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Russell JA, Vincent JL, Kjølbye AL, et al. Selepressin, a novel selective vasopressin V1A agonist, is an effective substitute for norepinephrine in a phase IIa randomized, placebo-controlled trial in septic shock patients. Crit Care. 2017;21(1):213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Svoboda P, Scheer P, Kantorová I, et al. Terlipressin in the treatment of late phase catecholamine-resistant septic shock. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59(116):1043-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagendran M, Maruthappu M, Gordon AC, Gurusamy KS. Comparative safety and efficacy of vasopressors for mortality in septic shock: a network meta-analysis. J Intensive Care Soc. 2016;17(2):136-145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gamper G, Havel C, Arrich J, et al. Vasopressors for hypotensive shock. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD003709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McIntyre WF, Connolly SJ, Healey JS. Atrial fibrillation occurring transiently with stress. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2018;33(1):58-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Belletti A, Musu M, Silvetti S, et al. Non-adrenergic vasopressors in patients with or at risk for vasodilatory shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tan J, Chen H, Chen X, Zhang D, He F. Vasopressin and its analog terlipressin versus norepinephrine in the treatment of septic shock: a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2016;9(7):14183-14190. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Russell JA, Fjell C, Hsu JL, et al. Vasopressin compared with norepinephrine augments the decline of plasma cytokine levels in septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(3):356-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barrett LK, Orie NN, Taylor V, Stidwill RP, Clapp LH, Singer M. Differential effects of vasopressin and norepinephrine on vascular reactivity in a long-term rodent model of sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(10):2337-2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith SM, Vale WW. The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8(4):383-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suzuki Y, Satoh S, Oyama H, Takayasu M, Shibuya M. Regional differences in the vasodilator response to vasopressin in canine cerebral arteries in vivo. Stroke. 1993;24(7):1049-1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. MEDLINE Search Strategy

eAppendix 2. EMBASE Search Strategy

eAppendix 3. Cochrane CENTRAL Search Strategy

eAppendix 4. Basis for Outcome Selection

eAppendix 5. Outcome Importance for Choice of Vasopressor in Patients With Vasodilatory Shock

eAppendix 6. Characteristics of Included Studies

eAppendix 7. Characteristics of Important Excluded Studies

eAppendix 8. Characteristics of Ongoing Studies

eAppendix 9. Risk of Bias Graphs: Review Authors’ Judgments About Each Risk of Bias Item Presented as Percentages Across All 23 Randomized Trials

eAppendix 10. Risk of Bias Summary: Review Authors’ Judgments About Each Risk of Bias Item for Each Included Study

eAppendix 11. Forest Plots for All Outcomes, Including Sensitivity Analyses

eAppendix 12. Funnel Plots

eAppendix 13. Reported lengths of stay in primary studies and transformation of median and interquartile range to mean and standarddeviation

eAppendix 14. Summary of Findings Table

eReferences.