Key Points

Question

Do genetic variants that are related to body fat distribution via lower levels of gluteofemoral (hip) fat or via higher levels of abdominal (waist) fat show associations with diabetes or coronary disease risk?

Findings

In genetic studies including up to 636 607 people, distinct polygenic risk scores for increased waist-to-hip ratio via lower gluteofemoral or via higher abdominal fat distribution were significantly associated with higher levels of cardiometabolic risk factors and higher risk for type 2 diabetes and coronary disease.

Meaning

Genetic mechanisms specifically linked to lower gluteofemoral or higher abdominal fat distribution may independently contribute to the relationship between body shape and cardiometabolic risk.

Abstract

Importance

Body fat distribution, usually measured using waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), is an important contributor to cardiometabolic disease independent of body mass index (BMI). Whether mechanisms that increase WHR via lower gluteofemoral (hip) or via higher abdominal (waist) fat distribution affect cardiometabolic risk is unknown.

Objective

To identify genetic variants associated with higher WHR specifically via lower gluteofemoral or higher abdominal fat distribution and estimate their association with cardiometabolic risk.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) for WHR combined data from the UK Biobank cohort and summary statistics from previous GWAS (data collection: 2006-2018). Specific polygenic scores for higher WHR via lower gluteofemoral or via higher abdominal fat distribution were derived using WHR-associated genetic variants showing specific association with hip or waist circumference. Associations of polygenic scores with outcomes were estimated in 3 population-based cohorts, a case-cohort study, and summary statistics from 6 GWAS (data collection: 1991-2018).

Exposures

More than 2.4 million common genetic variants (GWAS); polygenic scores for higher WHR (follow-up analyses).

Main Outcomes and Measures

BMI-adjusted WHR and unadjusted WHR (GWAS); compartmental fat mass measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglycerides, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, type 2 diabetes, and coronary disease risk (follow-up analyses).

Results

Among 452 302 UK Biobank participants of European ancestry, the mean (SD) age was 57 (8) years and the mean (SD) WHR was 0.87 (0.09). In genome-wide analyses, 202 independent genetic variants were associated with higher BMI-adjusted WHR (n = 660 648) and unadjusted WHR (n = 663 598). In dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry analyses (n = 18 330), the hip- and waist-specific polygenic scores for higher WHR were specifically associated with lower gluteofemoral and higher abdominal fat, respectively. In follow-up analyses (n = 636 607), both polygenic scores were associated with higher blood pressure and triglyceride levels and higher risk of diabetes (waist-specific score: odds ratio [OR], 1.57 [95% CI, 1.34-1.83], absolute risk increase per 1000 participant-years [ARI], 4.4 [95% CI, 2.7-6.5], P < .001; hip-specific score: OR, 2.54 [95% CI, 2.17-2.96], ARI, 12.0 [95% CI, 9.1-15.3], P < .001) and coronary disease (waist-specific score: OR, 1.60 [95% CI, 1.39-1.84], ARI, 2.3 [95% CI, 1.5-3.3], P < .001; hip-specific score: OR, 1.76 [95% CI, 1.53-2.02], ARI, 3.0 [95% CI, 2.1-4.0], P < .001), per 1-SD increase in BMI-adjusted WHR.

Conclusions and Relevance

Distinct genetic mechanisms may be linked to gluteofemoral and abdominal fat distribution that are the basis for the calculation of the WHR. These findings may improve risk assessment and treatment of diabetes and coronary disease.

This cohort study uses GWAS data to identify genetic variants associated with higher waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) via gluteofemoral vs abdominal fat distribution and to estimate the association between a polygenic score for higher WHR and blood pressure, lipids and glucose levels, and type 2 diabetes and CVD risk.

Introduction

The distribution of body fat is associated with the propensity of overweight individuals to manifest insulin resistance and its associated metabolic and cardiovascular complications.1,2,3,4,5 The waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) is a widely used, convenient, and robustly validated indicator of fat distribution and is linked to the risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary disease independently of body mass index (BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).1,2,3,4,5 This observation has been used to infer that accumulation of fat in the abdominal cavity is an independent causal contributor to cardiometabolic disease. While many studies support this assertion and plausible mechanisms have been proposed, WHR can also be increased by a reduction in its denominator, the hip circumference. Evidence from several different forms of partial lipodystrophy6,7 and functional studies of peripheral adipose storage compartments8,9,10 suggests that a primary inability to expand gluteofemoral or hip fat can also underpin subsequent cardiometabolic disease risk. Emerging evidence from the analysis of common genetic variants associated with greater insulin resistance but lower levels of hip fat suggests that similar mechanisms may also be relevant to the general population.11,12,13,14

In this study, large-scale human genetic data were used to investigate whether genetic variants related to body fat distribution via lower levels of gluteofemoral (hip) fat or via higher levels of abdominal (waist) fat are associated with type 2 diabetes or coronary disease risk.

Methods

Study Design

A multistage approach was adopted (Table 1). In stage 1, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of WHR with and without adjustment for BMI were performed to identify genetic variants associated with fat distribution. Stage 1 included data from participants of European ancestry in the UK Biobank study and summary statistics from previously published GWAS of the Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits (GIANT) Consortium.16 In stage 2, general, hip-, and waist-specific polygenic scores for higher WHR were derived using 202 genetic variants independently associated with WHR in stage 1. Stage 2 included data from participants of European ancestry in the UK Biobank and summary statistics from GIANT.16

Table 1. Summary of the Study Design.

| Stage and Aima | Independent Variables | Outcome Variables | Outcome Data Sources | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: genetic discovery (identify genetic variants associated with fat distribution) |

More than 2.4 million common genetic variants genome-wide | BMI-adjusted WHR (n = 660 648) and unadjusted WHR (n = 663 598) | UK Biobank; GIANT (summary statistics) | P < 5 × 10−8 in each analysis |

| Stage 2a: derivation of polygenic scores for higher WHRb

(select genetic variants into polygenic scores for higher WHR capturing different components of fat distribution) |

202 Independent genetic variants from stage 1 | Hip (n = 664 446) and waist (n = 683 549) circumference | UK Biobank; GIANT (summary statistics) | Hip- or waist-specific WHR-associated genetic variant: P < .001 for association with either hip or waist and at least P > .20 for association with the other |

| Stage 2b: polygenic score performance (assess polygenic scores performance using variance explained and F statistic) |

4 Polygenic scores for higher WHRb | BMI-adjusted WHR (N = 350 721)c | UK Biobank | F statistic >10 |

| Stage 3: polygenic score validation (association of polygenic scores for higher WHR with detailed compartmental fat distribution measures) |

Polygenic scores for higher WHR from stage 2b | Arm, trunk, abdominal, abdominal visceral, abdominal subcutaneous, gluteofemoral, leg fat mass, and abdominal/gluteofemoral fat mass ratio measured by DEXA (N = 18 330) | Fenland; EPIC-Norfolk; UK Biobank | P < .002 |

| Stage 4: cardiometabolic risk association (association of polygenic scores for higher WHR with cardiovascular risk factors and disease outcomes) |

Polygenic scores for higher WHR from stage 2b | Risk factors: systolic (n = 451 402) and diastolic (n = 451 415) blood pressure; fasting insulin (n = 108 557), fasting glucose (n = 133 010); triglycerides (n = 188 577), LDL-C (n = 188 577). Outcomes: type 2 diabetes (69 677 cases, 551 081 controls), coronary disease (85 358 cases, 551 249 controls) | Risk factors: UK Biobank; MAGIC (summary statistics); GLGC (summary statistics). Disease outcomes: UK Biobank; EPIC-InterAct; DIAGRAM (summary statistics); CARDIoGRAMplusC4D (summary statistics) | P < .002 for risk factors; P < .006 for disease outcomes |

Abbreviations: CARDIOGRAMplusC4D, Coronary Artery Disease Genome-wide Replication and Meta-analysis plus the Coronary Artery Disease Genetics Consortium; BMI, body mass index; DEXA, dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry; DIAGRAM, Diabetes Genetics Replication and Meta-analysis Consortium; EPIC, European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition; GIANT, Genetic Investigation of Anthropometric Traits Consortium; GLGC, Global Lipid Genetic Consortium; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; MAGIC, Meta-analyses of Glucose and Insulin-related Traits Consortium; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

Studies participating in each stage are described in details in the Methods section, Table 2, and eMethods 1 and eTables 1-3 in the Supplement.

The 4 polygenic scores included (1) general polygenic score for higher WHR including all 202 independent genetic variants from stage 1; (2) waist-specific polygenic score for higher WHR including 36 genetic variants associated with waist but not hip in stage 2a; (3) hip-specific polygenic score for higher WHR including 22 genetic variants associated with hip but not waist in stage 2a; and (4) general polygenic score for higher WHR including 144 genetic variants not included in the waist-specific or hip-specific polygenic scores.

Variance explained was estimated using linear regression models in unrelated participants of European ancestry in the UK Biobank.15

In stage 3, associations of polygenic scores with compartmental fat mass measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) were estimated in participants of European ancestry in the UK Biobank, Fenland, and EPIC-Norfolk studies. In stage 4, associations of polygenic scores with 6 cardiometabolic risk factors and with risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease were estimated using data from participants of European ancestry in the UK Biobank, the EPIC-InterAct case-cohort study, and summary statistics from 6 previously published GWAS. All studies were approved by local institutional review boards and ethics committees, and participants gave written informed consent.

Studies and Participants

The UK Biobank (data collection: 2006-2018) is a prospective population-based cohort study of people aged 40 to 69 years who were recruited from 2006 to 2010 from 22 centers located in urban and rural areas across the United Kingdom.15

Fenland (data collection: 2005-2018) is a prospective population-based cohort study of people born from 1950 to 1975 and recruited from 2005 to 2015 from outpatient primary care clinics in Cambridge, Ely, and Wisbech (United Kingdom).11

EPIC-Norfolk (data collection: 1993-2018) is a prospective population-based cohort study of individuals aged 40 to 79 years and living in Norfolk County (rural areas, market towns, and the city of Norwich) in the United Kingdom at recruitment from outpatient primary care clinics in 1993 to 1997.17

EPIC-InterAct (data collection: 1991-2018) is a case-cohort study nested within the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC), a prospective cohort study.18 EPIC study participants who developed type 2 diabetes after study baseline constituted the incident case group of EPIC-InterAct and a randomly selected group of individuals without diabetes at baseline constituted the subcohort.

Summary statistics from 11 GWAS published by research consortia between 2012 and 2015 were used in the different stages of the study (eMethods 1 and eTable 1 in the Supplement). These included genetic variant associations with BMI, BMI-adjusted WHR, unadjusted WHR, waist and hip circumference from the GIANT Consortium,16,19 associations with fasting glucose and fasting insulin from the Meta-analyses of Glucose and Insulin-related Traits Consortium (MAGIC),20,21 associations with triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) from the Global Lipid Genetics Consortium (GLGC),22 associations with type 2 diabetes from the Diabetes Genetics Replication and Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium23 and with coronary artery disease from the Coronary Artery Disease Genome-wide Replication and Meta-analysis plus the Coronary Artery Disease Genetics Consortium (CARDIOGRAMplusC4D).24 Data collection took place from 2012 to 2016.

Detailed descriptions of study design, sources of data, and participants in each stage are in Table 1 and Table 2, and eMethods 1 and eTables 1-3 in the Supplement.

Table 2. Participants of the UK Biobank Included in This Studya.

| Study | UK Biobankb |

|---|---|

| Participants, No. | 452 302 |

| Sex, No. (%) | |

| Men | 206 951 (46) |

| Women | 245 351 (54) |

| Age at baseline, mean (SD), y | 57 (8) |

| Men | 57 (8) |

| Women | 57 (8) |

| Currently smoking, No. (%) | 47 036 (10) |

| Men | 25 165 (12) |

| Women | 21 867 (9) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) [No. missing]c | 27.4 (4.8) [1594] |

| Men | 27.9 (4.2) |

| Women | 27.0 (5.1) |

| Waist-to-hip ratio, mean (SD) [No. missing] | 0.87 (0.09) [883] |

| Men | 0.94 (0.07) |

| Women | 0.82 (0.07) |

| Waist circumference, mean (SD) [No. missing], cm | 90 (13.5) [790] |

| Men | 97 (11.4) |

| Women | 85 (12.5) |

| Hip circumference, mean (SD) [No. missing], cm | 103 (9.2) [838] |

| Men | 104 (7.6) |

| Women | 103 (10.3) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SD) [No. missing], mm Hg | 138 (19) [863] |

| Men | 141 (17) |

| Women | 135 (19) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SD) [No. missing], mm Hg | 82 (10) [850] |

| Men | 84 (10) |

| Women | 81 (10) |

The exact numbers of participants included in each genetic analysis are in eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Genotyping in the UK Biobank was performed using the Affymetrix UK BILEVE and UK Biobank Axiom arrays, with Haplotype Reference Consortium r1.1 as the imputational panel.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Outcomes

Outcomes of the study were WHR (stages 1 and 2b), hip and waist circumference (stage 2a), compartmental body fat masses (stage 3), 6 cardiometabolic risk factors (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, triglycerides, and LDL-C; stage 4), and 2 disease outcomes (type 2 diabetes and coronary disease; stage 4).

In stages 1 and 2, WHR was defined as the ratio of the circumference of the waist to that of the hip, both of which were estimated in centimeters using a Seca 200-cm tape measure. BMI-adjusted WHR was obtained by calculating the residuals for a linear regression model of WHR on age, sex, and BMI.

In stage 3, compartmental fat masses were measured in grams by DEXA, a whole-body, low-intensity x-ray scan that precisely quantifies fat mass in different body regions. In the UK Biobank, DEXA measures were obtained using a GE-Lunar iDXA instrument. In the Fenland and EPIC-Norfolk studies, DEXA scans were performed using a Lunar Prodigy advanced fan beam scanner (GE Healthcare). Participants were scanned by trained operators using standard imaging and positioning protocols. All the images were manually processed by one trained researcher, who corrected DEXA demarcations according to a standardized procedure as illustrated and described in eFigure 1 and eMethods 1, respectively, in the Supplement. In brief, the arm region included the arm and shoulder area. The trunk region included the neck, chest, and abdominal and pelvic areas. The abdominal region was defined as the area between the ribs and the pelvis, and was enclosed by the trunk region. The leg region included all of the area below the lines that form the lower borders of the trunk. The gluteofemoral region included the hips and upper thighs, and overlapped both leg and trunk regions. The upper demarcation of this region was below the top of the iliac crest at a distance of 1.5 times the abdominal height. DEXA CoreScan software (GE Healthcare) was used to determine visceral abdominal fat mass within the abdominal region.

In stage 4, the risk factors included systolic and diastolic blood pressures, defined as the values of arterial blood pressure in mm Hg measured using an Omron monitor during the systolic and diastolic phases of the heart cycle. Fasting insulin and fasting glucose levels were defined as the values of insulin (log-transformed and expressed in log-pmol/L) in serum and glucose (mmol/L) in whole blood measured in fasting state in individuals without diabetes as previously described.20,21 Triglyceride (log-transformed and expressed in log-mmol/L) and LDL-C (mmol/L) levels in the circulation were measured using biochemical assays (triglycerides and 24% of LDL-C values in the GLGC study22) or derived with the Friedewald formula (76% of LDL-C values in the GLGC study22) as previously described.

For disease outcomes analyses in the UK Biobank in stage 4, binary definitions of prevalent disease status and a case-control analytical design were used in line with previous work.11,25,26 The definition of diabetes was consistent with validated algorithms.25 Participants were classified as cases of prevalent type 2 diabetes if they met the following 2 criteria: (1) self-reported type 2 diabetes diagnosis or self-reported diabetes medication at nurse interview or at digital questionnaire, or electronic health record consistent with type 2 diabetes (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems Tenth Revision code E11); and (2) age at diagnosis older than 36 years or use of oral antidiabetic medications (to remove likely type 1 diabetes cases). Controls were participants who (1) did not self-report a diagnosis of diabetes of any type, (2) did not take any diabetes medications, and (3) did not have an electronic health record of diabetes of any type.

In EPIC-InterAct, the outcome was incident type 2 diabetes. Incident type 2 diabetes case status was defined on the basis of evidence of type 2 diabetes from self-report, primary care registers, drug registers (medication use), hospital record, or mortality data.18 Incident type 2 diabetes cases were considered to be verified if evidence from a minimum of 2 of these independent sources was present.18 Participants without type 2 diabetes at baseline were randomly selected from participating EPIC study cohorts and constituted the subcohort group of EPIC-InterAct. Participants with prevalent diabetes at study baseline were excluded from EPIC-InterAct.

In the UK Biobank, prevalent coronary artery disease was defined as either (1) myocardial infarction or coronary disease documented in the participant’s medical history at the time of enrollment by a trained nurse or (2) an electronic health record of acute myocardial infarction or its complications (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision codes I21-I23). Controls were participants who did not meet any of these criteria.

Statistical Analysis

In stage 1, GWAS analyses were performed in the UK Biobank using BOLT-LMM,27 which fits linear mixed models accounting for relatedness between individuals using a genomic kinship matrix.27,28 An inverse-variance weighted, fixed-effect meta-analysis of results from the UK Biobank and GIANT was performed using METAL.29 This study focused on 2 446 094 common genetic variants in autosomal chromosomes (ie, not X or Y chromosome) with minor allele frequency of 0.5% or greater captured in both the UK Biobank and GIANT. Restriction to individuals of European ancestry, use of linear mixed models (UK Biobank), and adjustment for genetic principal components and genomic inflation factor (GIANT) were used to minimize type I error.

Quality measures of genuine genetic association signal vs possible confounding by population stratification or relatedness included the mean χ2 statistic, the linkage-disequilibrium score (LDSC) regression intercept, and its attenuation ratio (eMethods 2 in the Supplement), as recommended for genetic studies of this size using linear mixed model estimates.28 Values of LDSC-regression intercept below 1.5 and an attenuation ratio statistic (a measure of proportionality between LDSC-regression intercept and χ2 statistic calculated as: [LDSC intercept – 1] / [mean χ2 statistic – 1]) equal to or below 0.08 are consistent with optimal control of genetic confounding.28 Genetic variants were taken forward to stage 2 if they were associated with both BMI-adjusted WHR and unadjusted WHR at the conventional genome-wide level of statistical significance (P < 5 × 10−8 in each analysis).30 The use of both BMI-adjusted and unadjusted results prevented the inclusion of variants associated with higher WHR via collider bias31 or via a primary association with higher BMI.

A forward-selection process was used to select independent genetic variants for stage 2. At each iteration, the genetic variant with the lowest P value for BMI-adjusted WHR was selected, while genetic variants within 1 000 000 base pairs either side of that genetic variant were discarded from further iterations. The resulting list of genetic variants was further filtered on the basis of pairwise linkage disequilibrium such that the final list of independent genetic variants had no or negligible correlation (pairwise R2 < .05). Full details about genetic analyses are in eMethods 2 in the Supplement.

In stage 2, polygenic scores capturing genetic predisposition to higher WHR were derived by combining the 202 independent genetic variants from stage 1 (or subsets of the 202 variants as described below), weighted by their association with BMI-adjusted WHR in stage 1. A general polygenic score for higher WHR was derived by combining all 202 genetic variants. A waist-specific polygenic score capturing genetic predisposition to higher WHR via higher abdominal fat was derived by combining 36 variants specifically associated with waist (P < .00025, a Bonferroni correction for 202 genetic variants, 0.05/202) but not with hip circumference (P > .20, an arbitrary threshold). A hip-specific polygenic score capturing genetic predisposition to higher WHR via lower gluteofemoral fat was derived by combining 22 variants specifically associated with hip (P < .00025, 0.05/202) but not with waist circumference (P > .50, a stricter arbitrary threshold, which was necessary because of residual associations with waist circumference of a polygenic score initially derived using P > .20; eMethods 3 in the Supplement). A fourth polygenic score was derived by combining 144 genetic variants not included in the waist- or hip-specific polygenic scores.

The statistical performance of these polygenic scores was assessed by estimating the proportion of the variance in BMI-adjusted WHR accounted for by the score (variance explained) and by the F statistic (eMethods 4 in the Supplement). The F statistic is a measure of the ability of the polygenic score to predict the independent variable (BMI-adjusted WHR). Values of F statistic greater than 10 have been considered to provide evidence of a statistically robust polygenic score.26,32 Statistical power calculations for the association with disease outcomes were also performed (eMethods 4 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

In stages 3 and 4, associations of polygenic scores with DEXA phenotypes, cardiometabolic risk factors, and outcomes were estimated in each study separately and results were combined using fixed-effect inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis. In individual-level data analyses, polygenic scores were calculated for each study participant by adding the number of copies of each contributing genetic variant weighted by its association estimate in SD units of BMI-adjusted WHR per allele from stage 1. Association of polygenic scores with outcomes were estimated using linear, logistic, or Cox regression models as appropriate for outcome type and study design. Regression models were adjusted for age, sex, and genetic principal components or a genomic kinship matrix to minimize genetic confounding.

In UK Biobank disease outcomes analyses, prevalent disease status was defined as a binary variable and logistic regression was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) of disease per 1-SD increase in BMI-adjusted WHR due to a given polygenic score. In EPIC-InterAct, Cox regression weighted for case-cohort design was used to estimate the hazard ratio of incident type 2 diabetes per 1-SD increase in BMI-adjusted WHR due to a given polygenic score.

In summary statistics analyses, estimates equivalent to those of individual-level analyses were obtained using inverse-variance weighted meta-analysis of the association of each genetic variant in the polygenic score with the outcome, divided by the association of that genetic variant with BMI-adjusted WHR.33 These analytical approaches assume normal distributions for polygenic scores and continuous outcomes. They also assume a linear relationship of the polygenic score with continuous outcomes (linear regression), with the log-odds of binary outcomes (logistic regression), or with the log-hazard of incident disease (Cox regression). All of these assumptions were largely met in this study (eMethods 5, eTable 4, and eFigures 3-6 in the Supplement). Meta-analyses of log-ORs and log–hazard ratios of disease assumed that these estimates are similar, an assumption that was shown to be reasonable in a sensitivity analysis conducted in EPIC-InterAct (eMethods 5 and eFigure 7 in the Supplement).

In stages 3 and 4, associations with continuous outcomes were expressed in standardized or clinical units of outcome per 1-SD increase in BMI-adjusted WHR (corresponding to 0.056 ratio units of age-, sex-, and BMI-residualized WHR in the UK Biobank) due to a given polygenic score (eMethods 5 and eTable 5 in the Supplement). Associations with disease outcomes were expressed as ORs for outcome per 1-SD increase in BMI-adjusted WHR due to a given polygenic score. Absolute risk increases (ARIs) for disease outcomes were estimated using the estimated ORs and the incidence of type 2 diabetes or coronary disease in the United States (eMethods 5 in the Supplement). The threshold of statistical significance for association with DEXA phenotypes was P < .002 (0.05/32 = 0.0016, Bonferroni correction for 8 outcomes and 4 polygenic scores), P < .002 for association with cardiometabolic risk factors (0.05/24 = 0.0021, Bonferroni correction for 6 outcomes and 4 polygenic scores), and P < .006 for association with type 2 diabetes and coronary disease (0.05/8 = 0.0063, Bonferroni correction for 2 outcomes and 4 polygenic scores). All reported P values were from 2-tailed statistical tests.

In addition to deriving specific polygenic scores, the independent association of gluteofemoral or abdominal fat distribution with outcomes was studied using multivariable genetic association analyses adjusting for either of these 2 components of body fat distribution (eMethods 6 and eFigure 8 in the Supplement). Adjusting for abdominal fat distribution measures was used as a way of estimating the residual association of the polygenic score with outcomes via gluteofemoral fat distribution, while adjusting for gluteofemoral fat distribution measures as a way of estimating the residual association via abdominal fat distribution (eFigure 8 in the Supplement).

To obtain adjusted association estimates, multivariable-weighted regression models were fitted in which the association of the 202-variant general polygenic score (exposure) with cardiometabolic risk factors or diseases (outcomes) was estimated while adjusting for a polygenic score comprising the same 202 genetic variants but weighted for measures of abdominal fat distribution or measures of gluteofemoral fat distribution (covariates).34 A detailed description of these analysis methods and their assumptions is in eMethods 6 and eFigures 8-9 in the Supplement. This method was also used to conduct a post hoc exploratory analysis of the association of the hip-specific polygenic score with cardiometabolic disease outcomes after adjusting for visceral abdominal fat mass estimates.

Six different secondary or sensitivity analyses were conducted to estimate the association of polygenic scores with other phenotypes including high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglyceride/HDL-C ratio, height, and nondiabetic hyperglycemia and to assess the robustness of the main analysis to associations with height, sex-specific associations, or the possibility of false-positive associations in stage 1 or stage 2 (eMethods 7 in the Supplement).

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp), R version 3.2.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing), BOLT-LMM version 2.3.2,27,28 and METAL version 2011-03-25.29

Results

Genetic Predisposition to Higher WHR via Lower Gluteofemoral or via Higher Abdominal Fat

Among 452 302 participants of European ancestry in the UK Biobank, the mean (SD) age was 57 (8) years, 245 351 (54%) were women, and the mean (SD) WHR was 0.87 (0.09) (Table 2). In genome-wide association analyses of BMI-adjusted WHR (n = 660 648; mean χ2 = 2.50; LDSC-regression intercept, 1.098 [95% CI, 1.063-1.134]; attenuation ratio, 0.07 [95% CI, 0.04-0.09]) and unadjusted WHR (n = 663 598; mean χ2 = 2.68; LDSC-regression intercept, 1.096 [95% CI, 1.064-1.129]; attenuation ratio, 0.06 [95% CI, 0.04-0.08]), there was evidence of optimal control for genetic confounding (eMethods 2 and eFigures 10-11 in the Supplement).

A total of 202 independent genetic variants were associated with both BMI-adjusted WHR and unadjusted WHR (P < 5 × 10−8 in each analysis; eTable 6 and eFigures 12-13 in the Supplement). These 202 genetic variants were used to derive polygenic scores for higher WHR (Table 1). The 202-variant general score (variance in BMI-adjusted WHR explained by score in the UK Biobank = 3.4%, F statistic = 12 231), 22-variant hip-specific score (variance explained = 0.4%, F statistic = 1550), 36-variant waist-specific score (variance explained = 0.4%, F statistic = 1444), and 144-variant general score (variance explained = 2.6%, F statistic = 9177) were statistically robust polygenic scores for BMI-adjusted WHR (eMethods 4 and eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

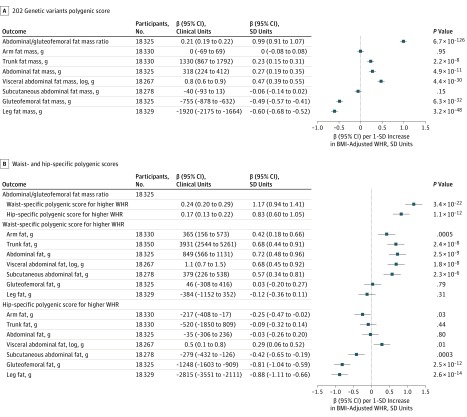

In 18 330 people with DEXA compartmental fat measures, all polygenic scores for higher WHR were associated with a higher abdominal-to-gluteofemoral fat mass ratio, a refined measure of body fat distribution, but were associated with different patterns of compartmental fat mass distribution (Figure 1; eFigures 14-15 in the Supplement). The general 202-variant and 144-variant polygenic scores were associated with higher visceral abdominal and lower gluteofemoral fat mass (Figure 1A; eFigure 15 in the Supplement). The waist-specific polygenic score for higher WHR was associated with higher abdominal fat mass, but not with gluteofemoral or leg fat mass (Figure 1B). The hip-specific polygenic score for higher WHR was associated with lower gluteofemoral and leg fat mass, but did not show statistically significant associations with abdominal fat mass (Figure 1B). Participants with higher values of the hip-specific polygenic score had numerically higher visceral abdominal fat mass, but the difference was not statistically significant when accounting for multiple tests (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Associations With Compartmental Fat Mass of Polygenic Scores for Higher Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR).

A, Associations with compartmental fat mass for the 202–genetic variants polygenic score for higher WHR are shown. Associations are reported in clinical or standardized units of continuous outcome per 1-SD increase in body mass index (BMI)–adjusted WHR (corresponding to 0.056 ratio units of age-, sex-, and BMI-residualized WHR in the UK Biobank) due to the polygenic score. The statistical significance threshold for analyses reported in this panel was P < .002. B, Associations with compartmental fat mass for the waist- or hip-specific polygenic scores for higher WHR are shown. Associations were estimated in up to 18 330 individuals of European ancestry in the UK Biobank,15 Fenland,11 and EPIC-Norfolk17 studies. Associations are reported in clinical or standardized units of continuous outcome per 1-SD increase in BMI-adjusted WHR (corresponding to 0.056 ratio units of age-, sex-, and BMI-residualized WHR in the UK Biobank) due to the polygenic score used in a given analysis. The statistical significance threshold for analyses reported in this panel was P < .002.

Associations With Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Disease Outcomes

In 636 607 people, the 202-variant polygenic score for higher WHR was associated with higher odds of type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease and an unfavorable cardiometabolic risk profile (eFigure 16 in the Supplement), consistent with previous studies of approximately 50 genetic variants.16,26,35 In secondary analyses, there were associations with lower HDL-C, higher triglyceride/HDL-C ratio, and higher odds of nondiabetic hyperglycemia (eMethods 7 and eTables 7-8 in the Supplement). Associations with cardiometabolic disease outcomes were similar in men and women, with no evidence of sex interaction (interaction P for type 2 diabetes = .19; interaction P for coronary artery disease = .80; eTable 9 in the Supplement).

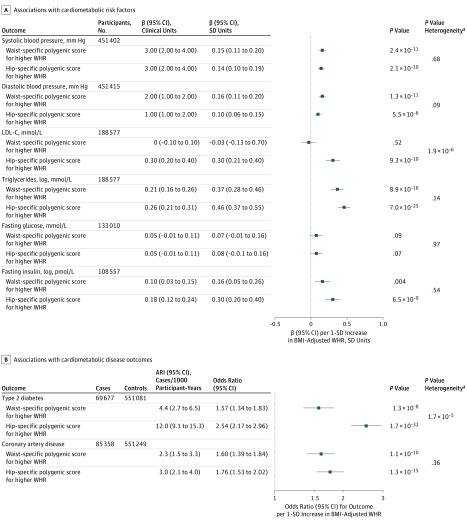

Both hip-specific and waist-specific polygenic scores for higher WHR were associated with higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure and triglyceride level, with similar association estimates for a 1-SD increase in BMI-adjusted WHR (Figure 2A). While the hip-specific polygenic score was associated with higher fasting insulin and higher LDL-C levels, the waist-specific polygenic score did not have statistically significant associations with these traits (Figure 2A). Both the hip-specific and waist-specific polygenic scores were associated with higher odds of type 2 diabetes and coronary disease, similarly in men and women (Figure 2B and eTable 9 in the Supplement). The hip-specific polygenic score had a statistically larger association estimate for diabetes than the waist-specific polygenic score per 1-SD increase in BMI-adjusted WHR (OR, 2.54 [95% CI, 2.17-2.96] vs 1.57 [95% CI, 1.34-1.83]; ARI, 12.0 [95% CI, 9.1-15.3] vs 4.4 [95% CI, 2.7-6.5] cases per 1000 participant-years; P for heterogeneity < .001; Figure 2B).

Figure 2. Associations With Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Disease Outcomes of Waist- or Hip-Specific Polygenic Scores for Higher Waist-to-Hip Ratio (WHR).

A, Associations with cardiometabolic risk factors for the waist- or hip-specific polygenic scores for higher WHR are shown. Associations are reported in clinical or standardized units of continuous outcome per 1-SD increase in body mass index (BMI)–adjusted WHR (corresponding to 0.056 ratio units of age-, sex-, and BMI-residualized WHR in the UK Biobank) due to the polygenic score used in a given analysis. Data on blood pressure were from the UK Biobank15; data on low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) and triglyceride levels were from the Global Lipids Genetics Consortium22; and data on fasting insulin and fasting glucose were from the Meta-analyses of Glucose and Insulin-Related Traits Consortium.20,21 The statistical significance threshold for analyses reported in this panel was P < .002. B, Associations with type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease risk for the waist- or hip-specific polygenic scores for higher WHR are shown. Associations are reported in odds ratio or absolute risk increase (ARI) per 1-SD increase in BMI-adjusted WHR (corresponding to 0.056 ratio units of age-, sex-, and BMI-residualized WHR in the UK Biobank) due to the polygenic score used in a given analysis. Associations with type 2 diabetes were estimated in 69 677 cases and 551 081 controls from the DIAGRAM Consortium,23 EPIC-InterAct,18 and the UK Biobank.15 Associations with coronary artery disease were estimated in 85 358 cases and 551 249 controls from the UK Biobank15 and the CARDIoGRAMplusC4D Consortium.24 The statistical significance threshold for analyses reported in this panel was P < .006.

aP value for heterogeneity in association estimates for waist- vs hip-specific polygenic score.

In a post-hoc multivariable analysis adjusting for visceral abdominal fat mass estimates, the hip-specific polygenic score showed a statistically significant association with higher odds of type 2 diabetes and coronary disease (OR for diabetes per 1-SD increase in BMI-adjusted WHR due to the hip-specific polygenic score, 2.84 [95% CI, 1.98-4.08], ARI, 14.4 [95% CI, 7.6-24] cases per 1000 participant-years, P < .001; OR for coronary disease, 1.74 [95% CI, 1.35-2.25], ARI, 2.9 [95% CI, 1.4-4.9] cases per 1000 participant-years, P < .001). The 144-variant polygenic score showed associations with risk factors and disease outcomes similar to those observed for the 202-variant general polygenic score (eFigure 15 in the Supplement). Sensitivity analyses supported the robustness of the main analysis to sex-specific associations, associations with height, or the possibility of false-positive associations in stage 1 or stage 2 (eMethods 7 and eTables 9-11 in the Supplement).

In multivariable analyses adjusting for hip circumference estimates, the 202-variant polygenic score had a pattern of association with compartmental fat mass, cardiometabolic risk factors, and disease outcomes, which was similar to that of the waist-specific polygenic score (eFigures 8D and 17 in the Supplement). The 202-variant polygenic score remained associated with higher risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary disease even when adjusting for hip circumference and leg fat mass in the same model (eTable 12 in the Supplement).

In multivariable analyses adjusting for waist circumference estimates, the 202-variant polygenic score had a pattern of association with compartmental fat mass, cardiometabolic risk factors, and disease outcomes, which was similar to that of the hip-specific polygenic score (eFigures 8C and 17 in the Supplement). The 202-variant polygenic score remained associated with higher risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary disease even when adjusting for waist circumference and visceral abdominal fat mass in the same model (eTable 12 in the Supplement).

In multivariable analyses adjusting for both waist and hip circumference estimates, the 202-variant polygenic score was not associated with risk of type 2 diabetes or coronary disease (eFigure 8B and eTable 12 in the Supplement).

Discussion

This large study identified distinct genetic variants associated with a higher WHR via specific associations with lower gluteofemoral or higher abdominal fat distribution. Both of these distinct sets of genetic variants were associated with higher levels of cardiometabolic risk factors and a higher risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary disease. While this study supports the theory that an enhanced accumulation of fat in the abdominal cavity may be a cause of cardiovascular and metabolic disease, it also provides novel evidence of a possible independent role of the relative inability to expand the gluteofemoral fat compartment.

Previous studies of approximately 50 genomic regions associated with BMI-adjusted WHR16 have shown an association between genetic predisposition to higher WHR and higher risk of cardiometabolic disease,26,35 mirroring the well-established BMI-independent association of a higher WHR with incident cardiovascular and metabolic disease in large-scale observational studies.2,3 While these results have been widely interpreted as supportive of the role of abdominal fat deposition in cardiometabolic risk independent of overall adiposity, the etiologic contribution of lower levels of gluteofemoral and peripheral fat to these associations has not been considered.

The results of this study support the hypothesis that an impaired ability to preferentially deposit excess calories in the gluteofemoral fat compartment leads to higher cardiometabolic risk in the general population. This is consistent with observations in severe forms of partial lipodystrophy6,7 and with the emerging evidence of a shared genetic background between extreme lipodystrophies and fat distribution in the general population.11 This large human genetic study adds to a growing body of evidence linking gluteofemoral and subcutaneous adipose tissue biology with a favorable metabolic profile.8,9,10 The hip-specific polygenic score for higher WHR was not significantly associated with measures of central fat in DEXA analyses and, in a post hoc analysis, its association with cardiometabolic disease outcomes was independent of visceral abdominal fat mass. These associations may perhaps reflect the secondary deposition within ectopic fat depots, such as liver, cardiac and skeletal muscle, and pancreas, of excess calories that cannot be accommodated in gluteofemoral fat.36,37

It has been hypothesized that the association between fat distribution and cardiometabolic risk is due to an enhanced deposition of intra-abdominal fat generating a molecular milieu that fosters abdominal organ insulin resistance.38 The results of this study support a role of abdominal fat distribution, but they also suggest that impaired gluteofemoral fat distribution may contribute to the relationship between body shape and cardiometabolic health outcomes.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, as this is an observational study, it cannot establish causality. Second, the discovery and characterization of genetic variants was conducted in a large data set but was limited to individuals of European ancestry. While the genetic determinants of anthropometric phenotypes may be partly shared across different ethnicities,16,39,40 further investigations in other populations and ethnicities will be required for a complete understanding of the genetic relationships between body shape and cardiometabolic risk. Third, this study was largely based on population-based cohorts, the participants of which are usually healthier than the general population, and used analytical approaches that deliberately minimized the influence of outliers, in this case people with extreme fat distribution. Genetic studies in people with extreme fat distribution may help broaden understanding of the genetic basis of this risk factor.

Fourth, while disease case definitions were based on widely adopted criteria, random misclassification of cases/controls cannot be excluded, which would bias association estimates toward the null. Fifth, absolute risk increase estimates are based on incidence rates and ORs calculated in different populations and therefore assume that these populations are similar. Sixth, P value thresholds used to exclude associations with the other component of fat distribution for genetic variants included in waist- or hip-specific polygenic scores were arbitrarily chosen, but are more stringent than traditionally used cutoffs (eg, P > .05) and polygenic score results were confirmed by multivariable genetic analyses, which were independent of such thresholds.

Seventh, this analysis focused on common genetic variants captured in both UK Biobank and GIANT and, by design, did not investigate the role of rare genetic variation or of other variants captured by dense imputation in the UK Biobank. Eighth, there was a statistically significant difference in the association of hip- vs waist-specific polygenic scores with diabetes risk, with greater estimated magnitude of association for the hip-specific polygenic score. However, given that the difference in absolute risk was small, this observation does not necessarily represent a strong signal of mechanistic difference or differential clinical importance in the relationship between the gluteofemoral vs abdominal components of fat distribution and diabetes risk.

Conclusions

Distinct genetic mechanisms may be linked to gluteofemoral and abdominal fat distribution that are the basis for the calculation of the waist-to-hip ratio. These findings may improve risk assessment and treatment of diabetes and coronary disease.

eMethods 1. Data Sources, Study Design, Measurements, and Phenotype Definitions

eMethods 2. Genetic Association Analyses

eMethods 3. Selection of Subsets of Genetic Variants Associated With Higher WHR via a Specific Association With Higher Waist Circumference, or via a Specific Association With Lower Hip Circumference

eMethods 4. Assessment of Performance and Statistical Power of Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR

eMethods 5. Assumptions and Interpretation of Association Analyses Between Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR and Outcome Traits

eMethods 6. Multivariable Genetic Association Analyses

eMethods 7. Secondary and Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 1. Participating Studies

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of 18,330 Individuals From the Fenland, EPIC-Norfolk. and UK Biobank Studies Who Underwent Detailed Anthropometric Measurements by Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry

eTable 3. Characteristics of Participants of the EPIC-InterAct Study Included in the Analysis

eTable 4. Difference in Age-, Sex- and BMI-Residualized WHR at Different Levels of the Distribution of Standardized BMI-Adjusted WHR Following the Inverse-Rank Normal Transformation

eTable 5. Standard Deviation Values Used to Convert Estimates Between Clinical and Standardized Units and Their Source

eTable 6. List of the 202 Independent Lead Genetic Variants Identified in Stage 1 Which Were Used to Derive Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR

eTable 7. Associations of Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR With Additional Continuous Phenotypes in Secondary Analyses

eTable 8. Associations of Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR With Nondiabetic Hyperglycemia

eTable 9. Association of Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR With Risk of Type 2 Diabetes and Coronary Artery Disease in Men and Women From the UK Biobank Study

eTable 10. Results of Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 11. Associations of the 202-Variant Polygenic Score for Higher WHR With Cardiometabolic Disease Outcomes in Multivariable Genetic Association Analyses Adjusting for Height

eTable 12. Associations of the 202 Genetic Variants With Risk of Cardiometabolic Disease Outcomes in Multivariable Genetic Analyses

eFigure 1. Compartmental Body Fat Mass Measurement by Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry

eFigure 2. Statistical Power Calculations

eFigure 3. Distribution of the Values of Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR in UK Biobank

eFigure 4. Distribution of the Values of Standardized Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure Outcome Variables in UK Biobank

eFigure 5. Linear Association Between Polygenic Score for Higher WHR and Outcomes

eFigure 6. Distribution of BMI-Adjusted WHR Variables in UK Biobank

eFigure 7. Correlation of Estimates From Weighted Cox and Logistic Regression Models in EPIC-InterAct

eFigure 8. Schematic Representation of Multivariable Polygenic Score Association Analysis

eFigure 9. Diagnostic Funnel Plots for the Association of the 202 Genetic Variants Included in the Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR and Type 2 Diabetes or Coronary Disease

eFigure 10. Manhattan and Quantile-Quantile Plot for the Genome-Wide Association Analysis of BMI-Adjusted WHR

eFigure 11. Manhattan and Quantile-Quantile Plot for the Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Unadjusted WHR

eFigure 12. Associations of the 202 Genetic Variants With BMI-Adjusted WHR in GIANT and UK Biobank

eFigure 13. Consistency of Stage 1 Associations After Exclusion of Cardiometabolic Disease Cases

eFigure 14. Associations With Hip, Waist Circumference and Body Mass Index of the Four Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR

eFigure 15. Associations With DEXA Variables, Cardio-metabolic Risk Factors and Disease Outcomes of the 144-Variant Polygenic Score for Higher WHR

eFigure 16. Associations with Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Disease Outcomes of the 202-Variant Polygenic Score for Higher WHR

eFigure 17. Associations With Anthropometry, Cardio-metabolic Risk Factors and disease outcomes of 202-Variant Polygenic Score for Higher WHR in Multivariable Genetic Association Analyses Adjusted for Genetic Associations With Hip or Waist Circumference

eReferences

References

- 1.Vague J. The degree of masculine differentiation of obesities: a factor determining predisposition to diabetes, atherosclerosis, gout, and uric calculous disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1956;4(1):20-34. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/4.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, et al. ; INTERHEART Study Investigators . Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27,000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study. Lancet. 2005;366(9497):1640-1649. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67663-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biggs ML, Mukamal KJ, Luchsinger JA, et al. Association between adiposity in midlife and older age and risk of diabetes in older adults. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2504-2512. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langenberg C, Sharp SJ, Schulze MB, et al. ; InterAct Consortium . Long-term risk of incident type 2 diabetes and measures of overall and regional obesity: the EPIC-InterAct case-cohort study. PLoS Med. 2012;9(6):e1001230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stefan N, Häring HU, Hu FB, Schulze MB. Metabolically healthy obesity: epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1(2):152-162. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70062-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garg A. Acquired and inherited lipodystrophies. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(12):1220-1234. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra025261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semple RK, Savage DB, Cochran EK, Gorden P, O’Rahilly S. Genetic syndromes of severe insulin resistance. Endocr Rev. 2011;32(4):498-514. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karpe F, Pinnick KE. Biology of upper-body and lower-body adipose tissue: link to whole-body phenotypes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(2):90-100. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rydén M, Andersson DP, Bergström IB, Arner P. Adipose tissue and metabolic alterations: regional differences in fat cell size and number matter, but differently: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(10):E1870-E1876. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahlman I, Rydén M, Brodin D, Grallert H, Strawbridge RJ, Arner P. Numerous genes in loci associated with body fat distribution are linked to adipose function. Diabetes. 2016;65(2):433-437. doi: 10.2337/db15-0828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lotta LA, Gulati P, Day FR, et al. ; EPIC-InterAct Consortium; Cambridge FPLD1 Consortium . Integrative genomic analysis implicates limited peripheral adipose storage capacity in the pathogenesis of human insulin resistance. Nat Genet. 2017;49(1):17-26. doi: 10.1038/ng.3714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott RA, Fall T, Pasko D, et al. ; RISC study group; EPIC-InterAct consortium . Common genetic variants highlight the role of insulin resistance and body fat distribution in type 2 diabetes, independent of obesity. Diabetes. 2014;63(12):4378-4387. doi: 10.2337/db14-0319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yaghootkar H, Scott RA, White CC, et al. Genetic evidence for a normal-weight “metabolically obese” phenotype linking insulin resistance, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2014;63(12):4369-4377. doi: 10.2337/db14-0318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaghootkar H, Lotta LA, Tyrrell J, et al. Genetic evidence for a link between favorable adiposity and lower risk of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease. Diabetes. 2016;65(8):2448-2460. doi: 10.2337/db15-1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sudlow C, Gallacher J, Allen N, et al. UK Biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12(3):e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shungin D, Winkler TW, Croteau-Chonka DC, et al. ; ADIPOGen Consortium; CARDIOGRAMplusC4D Consortium; CKDGen Consortium; GEFOS Consortium; GENIE Consortium; GLGC; ICBP; International Endogene Consortium; LifeLines Cohort Study; MAGIC Investigators; MuTHER Consortium; PAGE Consortium; ReproGen Consortium . New genetic loci link adipose and insulin biology to body fat distribution. Nature. 2015;518(7538):187-196. doi: 10.1038/nature14132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Day N, Oakes S, Luben R, et al. EPIC-Norfolk: study design and characteristics of the cohort: European Prospective Investigation of Cancer. Br J Cancer. 1999;80(suppl 1):95-103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langenberg C, Sharp S, Forouhi NG, et al. ; InterAct Consortium . Design and cohort description of the InterAct Project: an examination of the interaction of genetic and lifestyle factors on the incidence of type 2 diabetes in the EPIC Study. Diabetologia. 2011;54(9):2272-2282. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2182-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, et al. ; LifeLines Cohort Study; ADIPOGen Consortium; AGEN-BMI Working Group; CARDIOGRAMplusC4D Consortium; CKDGen Consortium; GLGC; ICBP; MAGIC Investigators; MuTHER Consortium; MIGen Consortium; PAGE Consortium; ReproGen Consortium; GENIE Consortium; International Endogene Consortium . Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518(7538):197-206. doi: 10.1038/nature14177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scott RA, Lagou V, Welch RP, et al. ; DIAbetes Genetics Replication and Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium . Large-scale association analyses identify new loci influencing glycemic traits and provide insight into the underlying biological pathways. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):991-1005. doi: 10.1038/ng.2385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Manning AK, Hivert MF, Scott RA, et al. ; DIAbetes Genetics Replication And Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium; Multiple Tissue Human Expression Resource (MUTHER) Consortium . A genome-wide approach accounting for body mass index identifies genetic variants influencing fasting glycemic traits and insulin resistance. Nat Genet. 2012;44(6):659-669. doi: 10.1038/ng.2274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willer CJ, Schmidt EM, Sengupta S, et al. ; Global Lipids Genetics Consortium . Discovery and refinement of loci associated with lipid levels. Nat Genet. 2013;45(11):1274-1283. doi: 10.1038/ng.2797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris AP, Voight BF, Teslovich TM, et al. ; Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium; Meta-Analyses of Glucose and Insulin-related Traits Consortium (MAGIC) Investigators; Genetic Investigation of ANthropometric Traits (GIANT) Consortium; Asian Genetic Epidemiology Network–Type 2 Diabetes (AGEN-T2D) Consortium; South Asian Type 2 Diabetes (SAT2D) Consortium; DIAbetes Genetics Replication And Meta-analysis (DIAGRAM) Consortium . Large-scale association analysis provides insights into the genetic architecture and pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):981-990. doi: 10.1038/ng.2383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nikpay M, Goel A, Won HH, et al. A comprehensive 1,000 genomes-based genome-wide association meta-analysis of coronary artery disease. Nat Genet. 2015;47(10):1121-1130. doi: 10.1038/ng.3396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eastwood SV, Mathur R, Atkinson M, et al. Algorithms for the capture and adjudication of prevalent and incident diabetes in UK Biobank. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0162388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emdin CA, Khera AV, Natarajan P, et al. Genetic association of waist-to-hip ratio with cardiometabolic traits, type 2 diabetes, and coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2017;317(6):626-634. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.21042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loh PR, Tucker G, Bulik-Sullivan BK, et al. Efficient Bayesian mixed-model analysis increases association power in large cohorts. Nat Genet. 2015;47(3):284-290. doi: 10.1038/ng.3190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loh PR, Kichaev G, Gazal S, Schoech AP, Price AL. Mixed-model association for Biobank-scale datasets. Nat Genet. 2018;50(7):906-908. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0144-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willer CJ, Li Y, Abecasis GR. METAL: fast and efficient meta-analysis of genomewide association scans. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(17):2190-2191. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447(7145):661-678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aschard H, Vilhjálmsson BJ, Joshi AD, Price AL, Kraft P. Adjusting for heritable covariates can bias effect estimates in genome-wide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(2):329-339. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.12.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stock JHWJ, Yogo M. A survey of weak instruments and weak identification in generalized method of moments. J Bus Econ Stat. 2002;20(4):518-529. doi: 10.1198/073500102288618658 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burgess S, Butterworth A, Thompson SG. Mendelian randomization analysis with multiple genetic variants using summarized data. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37(7):658-665. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burgess S, Thompson DJ, Rees JMB, Day FR, Perry JR, Ong KK. Dissecting causal pathways using mendelian randomization with summarized genetic data: application to age at menarche and risk of breast cancer. Genetics. 2017;207(2):481-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dale CE, Fatemifar G, Palmer TM, et al. ; UCLEB Consortium; METASTROKE Consortium . Causal associations of adiposity and body fat distribution with coronary heart disease, stroke subtypes, and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a mendelian randomization analysis. Circulation. 2017;135(24):2373-2388. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Danforth E., Jr Failure of adipocyte differentiation causes type II diabetes mellitus? Nat Genet. 2000;26(1):13. doi: 10.1038/79111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Virtue S, Vidal-Puig A. Adipose tissue expandability, lipotoxicity and the metabolic syndrome: an allostatic perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1801(3):338-349. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haslam DW, James WP. Obesity. Lancet. 2005;366(9492):1197-1209. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67483-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kan M, Auer PL, Wang GT, et al. ; NHLBI-Exome Sequencing Project . Rare variant associations with waist-to-hip ratio in European-American and African-American women from the NHLBI-Exome Sequencing Project. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24(8):1181-1187. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chu AY, Deng X, Fisher VA, et al. Multiethnic genome-wide meta-analysis of ectopic fat depots identifies loci associated with adipocyte development and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2017;49(1):125-130. doi: 10.1038/ng.3738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. Data Sources, Study Design, Measurements, and Phenotype Definitions

eMethods 2. Genetic Association Analyses

eMethods 3. Selection of Subsets of Genetic Variants Associated With Higher WHR via a Specific Association With Higher Waist Circumference, or via a Specific Association With Lower Hip Circumference

eMethods 4. Assessment of Performance and Statistical Power of Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR

eMethods 5. Assumptions and Interpretation of Association Analyses Between Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR and Outcome Traits

eMethods 6. Multivariable Genetic Association Analyses

eMethods 7. Secondary and Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 1. Participating Studies

eTable 2. Baseline Characteristics of 18,330 Individuals From the Fenland, EPIC-Norfolk. and UK Biobank Studies Who Underwent Detailed Anthropometric Measurements by Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry

eTable 3. Characteristics of Participants of the EPIC-InterAct Study Included in the Analysis

eTable 4. Difference in Age-, Sex- and BMI-Residualized WHR at Different Levels of the Distribution of Standardized BMI-Adjusted WHR Following the Inverse-Rank Normal Transformation

eTable 5. Standard Deviation Values Used to Convert Estimates Between Clinical and Standardized Units and Their Source

eTable 6. List of the 202 Independent Lead Genetic Variants Identified in Stage 1 Which Were Used to Derive Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR

eTable 7. Associations of Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR With Additional Continuous Phenotypes in Secondary Analyses

eTable 8. Associations of Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR With Nondiabetic Hyperglycemia

eTable 9. Association of Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR With Risk of Type 2 Diabetes and Coronary Artery Disease in Men and Women From the UK Biobank Study

eTable 10. Results of Sensitivity Analyses

eTable 11. Associations of the 202-Variant Polygenic Score for Higher WHR With Cardiometabolic Disease Outcomes in Multivariable Genetic Association Analyses Adjusting for Height

eTable 12. Associations of the 202 Genetic Variants With Risk of Cardiometabolic Disease Outcomes in Multivariable Genetic Analyses

eFigure 1. Compartmental Body Fat Mass Measurement by Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry

eFigure 2. Statistical Power Calculations

eFigure 3. Distribution of the Values of Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR in UK Biobank

eFigure 4. Distribution of the Values of Standardized Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure Outcome Variables in UK Biobank

eFigure 5. Linear Association Between Polygenic Score for Higher WHR and Outcomes

eFigure 6. Distribution of BMI-Adjusted WHR Variables in UK Biobank

eFigure 7. Correlation of Estimates From Weighted Cox and Logistic Regression Models in EPIC-InterAct

eFigure 8. Schematic Representation of Multivariable Polygenic Score Association Analysis

eFigure 9. Diagnostic Funnel Plots for the Association of the 202 Genetic Variants Included in the Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR and Type 2 Diabetes or Coronary Disease

eFigure 10. Manhattan and Quantile-Quantile Plot for the Genome-Wide Association Analysis of BMI-Adjusted WHR

eFigure 11. Manhattan and Quantile-Quantile Plot for the Genome-Wide Association Analysis of Unadjusted WHR

eFigure 12. Associations of the 202 Genetic Variants With BMI-Adjusted WHR in GIANT and UK Biobank

eFigure 13. Consistency of Stage 1 Associations After Exclusion of Cardiometabolic Disease Cases

eFigure 14. Associations With Hip, Waist Circumference and Body Mass Index of the Four Polygenic Scores for Higher WHR

eFigure 15. Associations With DEXA Variables, Cardio-metabolic Risk Factors and Disease Outcomes of the 144-Variant Polygenic Score for Higher WHR

eFigure 16. Associations with Cardiometabolic Risk Factors and Disease Outcomes of the 202-Variant Polygenic Score for Higher WHR

eFigure 17. Associations With Anthropometry, Cardio-metabolic Risk Factors and disease outcomes of 202-Variant Polygenic Score for Higher WHR in Multivariable Genetic Association Analyses Adjusted for Genetic Associations With Hip or Waist Circumference

eReferences