Abstract

This study examined the rates of patients in the United Kingdom treated with gabapentin and pregabalin for the first time, and the rates of these patients with an off-label indication or a coprescription of opioids or benzodiazepines.

The gabapentinoid drugs gabapentin and pregabalin are approved for epilepsy, neuropathic pain, and generalized anxiety disorders (pregabalin only), and listed as an indication for migraines (gabapentin only) in the United Kingdom. These indications differ in other countries. Gabapentinoid prescriptions increased in the United States between 2002 and 2015,1 which may be partly related to an increase in off-label use.2 These medications have the potential for misuse and addiction and for overdose, when used in combination with opioids.3 In April 2019, the UK government will reclassify gabapentinoids as class C controlled substances.4 We estimated the rates of patients treated with gabapentin and pregabalin for the first time in the UK primary care system since these drugs were first licensed in 1993 and 2004, respectively.

Methods

Using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), a UK database of primary care medical records from more than 15 million patients,5 we identified all patients registered for at least one day between 1993 and 2017, with follow-up starting on January 1, 1993, or the patient’s registration date with the practice, whichever came later. Follow-up ended at the date the patient transferred out of the practice, the date of the patient’s death, or December 31, 2017, whichever occurred first. We used Poisson regression to estimate the annual rates of patients newly treated with gabapentin and pregabalin, separately, estimating rate ratios (RRs) over the last 10 years. For each patient with a first prescription, we identified same-day prescriptions for opiates and/or benzodiazepines (including sedatives). We inferred the indication corresponding to their first prescription using relevant diagnostic codes up to 1 year before this first prescription. Indication was classified in a hierarchical manner into 1 of 3 mutually exclusive categories: approved, off-label (nonneuropathic pain, other), or unknown.

The study protocol was approved by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee of the CPRD and the research ethics committee of the Jewish General Hospital, which also waived the need for patient informed consent. All analyses were conducted with SAS, version 9.4 (SAS institute).

Results

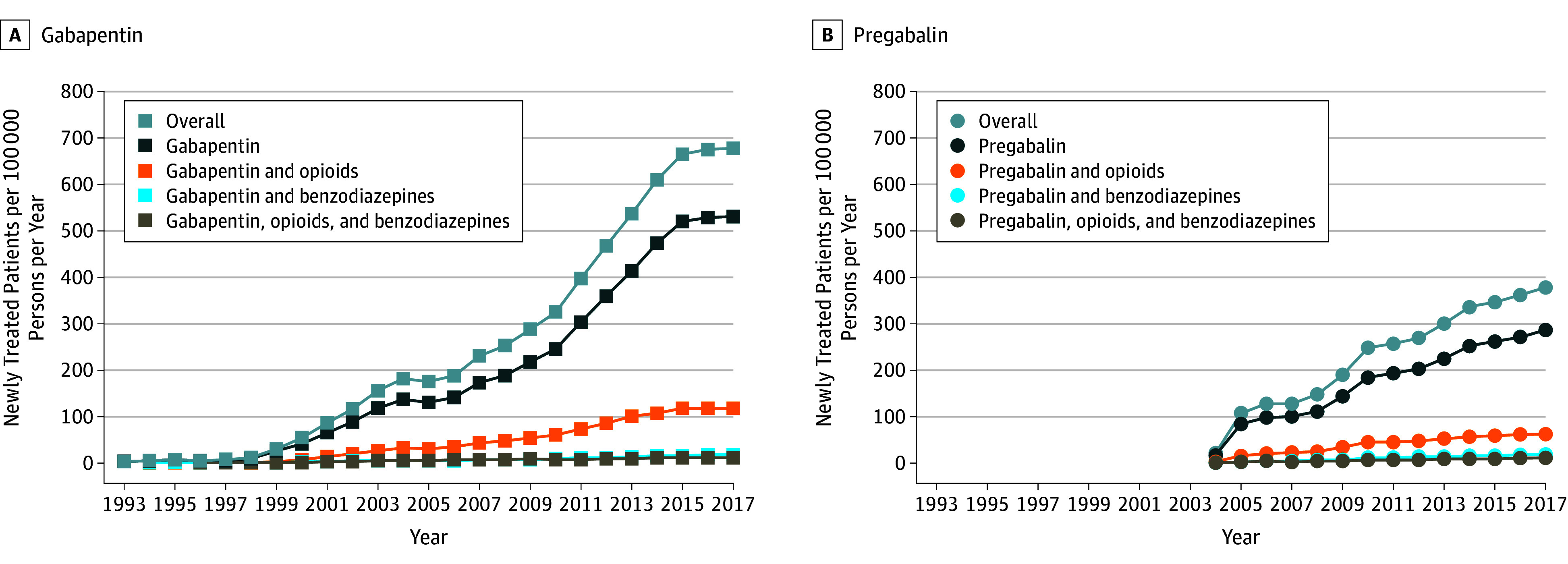

From 12 512 468 patients, we identified 256 410 (2.0%) who were newly treated with gabapentin and 136 653 (1.1%) with pregabalin. From 2007 to 2017, the rate of patients newly treated increased from 230 to 679 per 100 000 persons per year for gabapentin (RR, 2.95 [95% CI, 2.88-3.02]) and from 128 to 379 per 100 000 persons per year for pregabalin (RR, 2.96 [95% CI, 2.87-3.05]) (Figure 1). The rate of patients with a coprescription for opioids and/or benzodiazepines also increased from 56.4 to 148.1 per 100 000 persons per year for gabapentin (RR, 2.62 [95% CI, 2.50-2.76]) and from 28.7 to 91.2 per 100 000 persons per year for pregabalin (RR, 3.18 [95% CI, 2.98-3.40]). In 2017, 21.8% of patients newly treated with gabapentin and 24.1% newly treated with pregabalin received a concomitant prescription, primarily for opioids.

Figure 1. New Users of Gabapentin and Pregabalin in the UK Primary Care System from 1993 to 2017a.

Rates of new users of gabapentin (A) and pregabalin (B) in the UK primary care system documented in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink from 1993 to 2017.

aGabapentin and pregabalin were licensed in United Kingdom in 1993 and 2004, respectively.

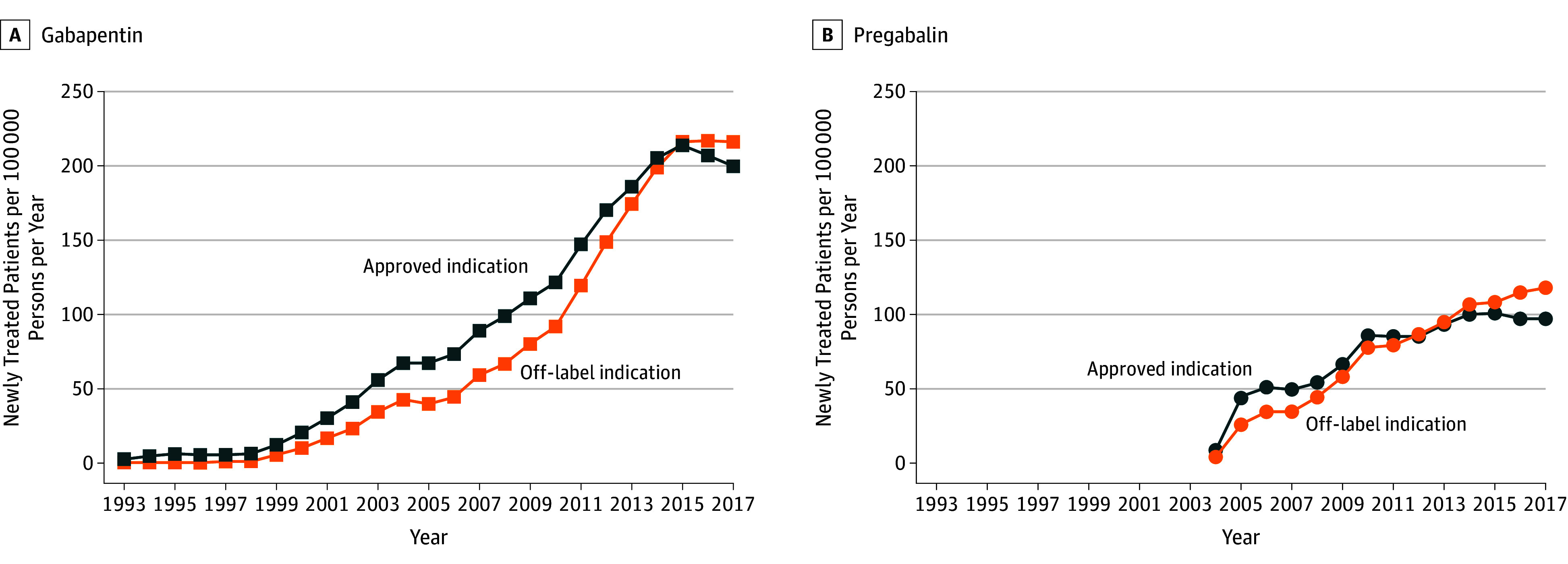

We identified a prescription indication for 64.2% of patients newly treated with gabapentin and 63.2% of patients newly treated with pregabalin. The rate of patients with an off-label indication increased from 58.7 to 216.0 per 100 000 persons per year for gabapentin (RR, 3.68 [95% CI, 3.52-3.85]) and from 34.7 to 117.8 per 100 000 persons per year for pregabalin (RR, 3.40 [95% CI, 3.20-3.60]) (Figure 2). Off-label prescriptions accounted for 52.0% of gabapentin and 54.8% of pregabalin prescriptions with an identified indication in 2017. Nonneuropathic pain accounted for 80.4% of gabapentin and 58.3% of pregabalin off-label prescriptions.

Figure 2. New Users With a Gabapentin and Pregabalin Indicationa in the UK Primary Care System From 1993 to 2017b.

Rates of new users with an identified gabapentin and pregabalin indication in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink from 1993 to 2017. aApproved gabapentinoid indications in the United Kingdom include epilepsy, neuropathic pain, migraines (gabapentin), and generalized anxiety disorder (pregabalin). Off-label indications were defined as nonneuropathic pain, migraines (pregabalin), generalized anxiety disorder (gabapentin), fibromyalgia, substance withdrawal, and others (eg, psychiatric disease, tremor, restless legs syndrome).

bPatients for whom a prescription indication could not be identified were not included.

Discussion

The rate of patients newly treated with gabapentinoids has tripled from 2007 to 2017 in primary care in the United Kingdom. By 2017, 50% of gabapentinoid prescriptions were for an off-label indication and 20% had a coprescription for opioids.

The study had some limitations. Prescription indications were inferred from patients’ medical history. An indication was identified for 60% of all patients newly treated because indications are not systematically recorded in the CPRD for each issued prescription, which could lead to misclassification. Also, only primary care practices were included. However, as general practitioners are central to the UK health system, most gabapentinoid prescriptions were likely issued by general practitioners, even when the treatment was initiated by a specialist.

Given the safety concerns of gabapentinoids and the lack of robust evidence supporting their efficacy in cases of nonneuropathic pain,6 caution is necessary when prescribing gabapentinoids, especially among patients also prescribed opioids.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Johansen ME. Gabapentinoid use in the United States 2002 Through 2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(2):292-294. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.7856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodman CW, Brett AS. Gabapentin and Pregabalin for Pain - Is Increased Prescribing a Cause for Concern? N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):411-414. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1704633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomes T, Juurlink DN, Antoniou T, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, van den Brink W. Gabapentin, opioids, and the risk of opioid-related death: A population-based nested case-control study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(10):e1002396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iacobucci G. UK government to reclassify pregabalin and gabapentin after rise in deaths. BMJ. 2017;358:j4441. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, et al. Data Resource Profile: Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD). Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(3):827-836. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyv098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wallach JD, Ross JS. Gabapentin Approvals, Off-Label Use, and Lessons for Postmarketing Evaluation Efforts. JAMA. 2018;319(8):776-778. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.21897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]