Abstract

Background

Australia has unrestricted access to direct-acting antivirals (DAA) for hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment. In order to increase access to treatment, primary care providers are able to prescribe DAA after fibrosis assessment and specialist consultation. Transient elastography (TE) is recommended prior to commencement of HCV treatment; however, TE is rarely available outside secondary care centres in Australia and therefore a requirement for TE could represent a barrier to access to HCV treatment in primary care.

Objectives

In order to bridge this access gap, we developed a community-based TE service across the Sunshine Coast and Wide Bay areas of Queensland.

Design

Retrospective analysis of a prospectively recorded HCV treatment database.

Interventions

A nurse-led service equipped with two mobile Fibroscan units assesses patients in eight locations across regional Queensland. Patients are referred into the service via primary care and undergo nurse-led TE at a location convenient to the patient. Patients are discussed at a weekly multidisciplinary team meeting and a treatment recommendation made to the referring GP. Treatment is initiated and monitored in primary care. Patients with cirrhosis are offered follow-up in secondary care.

Results

327 patients have undergone assessment and commenced treatment in primary care. Median age 48 years (IQR 38–56), 66% male. 57% genotype 1, 40% genotype 3; 82% treatment naïve; 10% had cirrhosis (liver stiffness >12.5 kPa). The majority were treated with sofosbuvir-based regimens. 26% treated with 8-week regimens. All patients had treatment prescribed and monitored in primary care. Telephone follow-up to confirm sustained virological response (SVR) was performed by clinic nurses. 147 patients remain on treatment. 180 patients have completed treatment. SVR data were not available for 19 patients (lost to follow-up). Intention-to-treat SVR rate was 85.5%. In patients with complete data SVR rate was 95.6%.

Conclusion

Community-based TE assessment facilitates access to HCV treatment in primary care with excellent SVR rates.

Keywords: hepatitis c, primary care, antiviral therapy

Introduction

Globally, up to 80 million people are estimated to be living with hepatitis C virus infection (HCV).1 Despite highly effective and well-tolerated treatment, the global burden of disease is projected to increase due to an ageing population, lack of access to treatment and failure to identify infected individuals.2 3

HCV infection is estimated to affect 230 000 Australians. Until 2015, treatment uptake was low with only 2000–4000 people treated per year.4 Contributing factors to this low uptake included complexity of treatment and limited tolerability of interferon-based regimens.5 The advent of direct-acting antivirals (DAA) revolutionised treatment and the majority of patients can now be cured with regimens of high efficacy and tolerability.

In March 2016, DAA were made freely available to all Australians with HCV regardless of disease stage. Since then an estimated 32 400 patients were treated (14% of the HCV-infected population) putting Australia in a position to realise the goal of HCV elimination in line with WHO targets.6

Despite initial success, maximising treatment uptake remains challenging. Many Australians living with HCV are situated in regional and remote areas with limited access to specialist services.7 Other patient groups including persons who inject drugs, persons in custodial settings and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are often disadvantaged by poor linkage to specialist services.8–10

Models of care addressing the challenges of providing treatment to patients in remote areas and marginalised groups are urgently required.11 12

All medical practitioners in Australia, especially those in primary care are able to prescribe DAA. Primary care practitioners must be experienced in treatment of HCV or prescribe after consultation with a specialist. An assessment of fibrosis is also required. Fibrosis assessment is recommended as cirrhosis affects treatment choice, duration and the need for surveillance for complications such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and gastro-oesophageal varices. Transient elastography (TE) is currently recommended for fibrosis assessment; however, TE is not widely available outside larger centres and therefore access to TE represents a barrier to treatment in primary care.13 Where TE is unavailable, the use of serum-based tests (NIT) such as aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio index (APRI) has been proposed as an alternative to identify patients with advanced fibrosis.14

In order to increase linkage to care and facilitate rapid access to DAA therapy, we developed and assessed new models of HCV care.

We aimed to facilitate treatment of HCV in primary care by increasing access to TE in addition to identifying patients with advanced fibrosis. We also sought to assess the performance of APRI in a primary care population to determine if APRI was sufficient to exclude advanced fibrosis in the primary care setting.

This study reports outcomes of these models of care and performance of NIT for the assessment of fibrosis compared with TE in a primary care population.

Methods

Data collection

Demographics, medical history, HCV treatment history, serology, liver function tests, TE data, DAA treatment and SVR data were recorded prospectively in a dedicated database and analysed retrospectively.

Treatment models

Our centre is based at a Sunshine Coast University Hospital (SCUH), a tertiary hospital in regional Queensland, Australia. In addition to traditional secondary care where patients are assessed and treated in hepatology clinics, two further models of care for the management of HCV were developed.

Model 1

Rapid evaluation liver clinic (RELIC): RELIC is a rapid access HCV treatment clinic. Patients are referred by their general practitioner (GP) with a dataset comprising liver biochemistry, HCV genotype and viral load, hepatitis B and HIV serology. Patients are seen by a hepatologist and nurse and following assessment including TE, a DAA treatment recommendation is made via a proforma which contains drug-drug interaction (DDI) information and a checklist for follow-up. The checklist provides information regarding hepatitis B reactivation, recommendations for hepatitis B vaccination and timing of blood tests to determine SVR. Of note, routine blood tests other than a 12-week post-treatment HCV RNA to confirm SVR (SVR12) were not recommended. Patients with suspected cirrhosis or who are complex are offered follow-up in secondary care. All others undergo treatment and follow-up in primary care. Nurses contact the patient following the clinic to ensure treatment has been initiated and determine the SVR12 date. Waiting time for assessment in the RELIC clinic is 14–28 days.

Model 2

The Hepatology Partnership Programme (HP): The HP programme is a nurse-led TE-based outreach service funded by Queensland Health and the Australian Centre for Health Services Innovation. Two nurses experienced in the assessment of HCV, equipped with mobile Fibroscan machines provide TE-based assessment clinics in regional settings throughout the SCUH catchment area. Currently, these clinics take place in regional health centres situated up to 800 km from the main centre, including a large prison. Patients are referred directly to the service from GPs with a data set as described above. Following assessment, patients are discussed at a weekly multidisciplinary team meeting and a treatment recommendation is made. A proforma containing the treatment recommendation and prescribing information is completed and transmitted electronically to the GP. As in the RELIC clinic, nurses contact the patient to ensure treatment has started and patients with cirrhosis are offered follow-up in the hepatology clinic, although this does not delay commencement of DAA therapy. The current waiting time for assessment in the HP is <2 weeks.

Validation of non-invasive serum tests for the diagnosis of cirrhosis

Australian guidelines recommend that APRI can be used instead of TE to exclude cirrhosis prior to commencing DAA. Currently, APRI<1 is considered sufficient to exclude cirrhosis. We calculated APRI for 295 primary care patients with complete and contemporaneous TE and biochemical data. We calculated the sensitivity (Sn), specificity (Sp), positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of APRI for excluding cirrhosis using TE (cutoff <12.5 kPa) as a gold standard.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.22. Data are presented as median and IQR. Proportions were compared using the Χ2 test. Results were considered statistically significant if p value was <0.05.

Results

From 1 March 2016 to 31 March 2018, 878 patients have commenced DAA therapy; 551 through secondary care and 327 via primary care.

Demographics

Of 878 patients undergoing treatment, 66% were male, 53% genotype 1 and 78% treatment naïve; 64% had mild fibrosis (≤F2) but >25% were cirrhotic according to TE values (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of patients treated with DAA

| Age, median (IQR) | 53 (43–58) |

| Sex—male (%) | 66 |

| Genotype (%) | |

| 1a | 43 |

| 1b | 10 |

| 2 | 5 |

| 3 | 40 |

| Other | 2 |

| Fibrosis stage (%) | |

| F0 | 18 |

| F1 | 30 |

| F2 | 16 |

| F3 | 10 |

| F4 | 26 |

| Treatment history (%) | |

| Naïve | 78 |

| TE no PI | 18 |

| TE and PI | 3 |

| Prior DAA failure | 1 |

| Duration of treatment, weeks (%) | |

| 8 | 15 |

| 12 | 70 |

| 24 | 15 |

DAA, direct-acting antiviral agent; PI, protease inhibitor; TE, treatment experienced.

Treatment allocation

Three hundred twenty-seven patients were treated in primary care and were assessed in the RELIC clinic (n=76) or in the community via the HP (n=251). Compared with patients treated in secondary care, patients treated in primary care were significantly younger, more frequently treatment naïve and less likely to have advanced fibrosis (table 2).

Table 2.

Comparison of primary care treated patients (n=327) compared with patients treated in secondary care (n=551)

| Primary care | Secondary care | P values | |

| Age (median and IQR) | 48 (38–56) | 54 (46–59) | <0.0001 |

| Sex—male (%) | 66 | 66 | NS |

| Genotype (%) | |||

| 1a | 46 | 41 | NS |

| 1b | 10 | 10 | NS |

| 2 | 2 | 7 | <0.05 |

| 3 | 40 | 40 | NS |

| Other | 2 | 2 | NS |

| Treatment history (%) | |||

| Naïve | 92 | 75 | <0.05 |

| TE no PI | 6 | 18 | <0.05 |

| TE and PI | 1 | 6 | NS |

| Prior DAA failure | 1 | 1 | NS |

| Duration of treatment, weeks (%) | |||

| 8 | 26 | 11 | <0.001 |

| 12 | 72 | 66 | NS |

| 24 | 2 | 23 | <0.05 |

| Fibrosis stage (%) | |||

| F0 | 22 | 16 | <0.05 |

| F1 | 40 | 23 | <0.05 |

| F2 | 18 | 15 | NS |

| F3 | 10 | 11 | NS |

| F4 | 10 | 35 | <0.05 |

DAA, direct- acting antiviral agent; NS, not significant; PI, protease inhibitor; TE, treatment experienced.

Change in treatment allocation over time

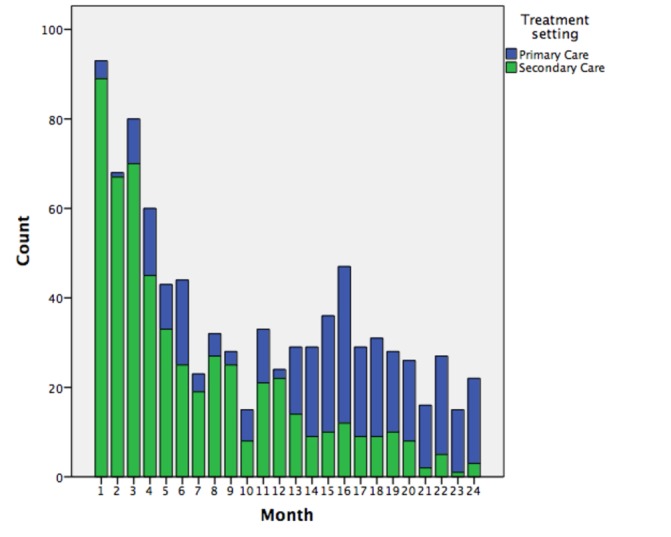

From the date of DAA availability (1 March 2016), a large number of patients were treated with DAA via secondary care. These patients had been ‘warehoused’, that is, already known to the service and awaiting treatment. Following the first 3 months of DAA availability, the number of patients commencing treatment declined. The introduction of the HP programme in month 12 of the programme resulted in a significant increase in the number of patients accessing treatment, the majority of whom were treated in primary care. Prescriptions in primary care accounted for 13.7% of prescriptions in the first 6 months from DAA availability increasing to over 80% in the most recent 6 months of the service (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Overall more patients were treated within secondary care but the number of patients treated in primary care through rapid evaluation liver clinic and hepatology partnership programme increased over time.

Sustained virological response data

In the total cohort (n=878), two patients died while on treatment or awaiting SVR data and 38 (4.3%) have been lost to follow-up. SVR12 data are available for 628 patients (467 secondary care, 161 primary care). Two hundred ten patients (147 in primary care and 63 in secondary care) remain on treatment or are awaiting SVR12 confirmation. Intention-to-treat SVR rate in the whole cohort is 88.6%. In patients with complete data, the SVR rate is 97.1%. In primary care treated patients the SVR rate in patients who had complete data (n=161) was 95.6%, whereas in patients in secondary care patients (n=467) the SVR rate was 97.6% (P=NS). Missing SVR12 data was seen more frequently in the primary care cohort than the secondary care cohort (11% vs 4%, p=0.02). Prescribed DAA regimens according to genotype are presented in table 3.

Table 3.

DAA treatment regimen according to genotype

| Treatment regimen | Genotype 1 (%) | Genotype 2 (%) | Genotype 3(%) | Genotype 4 (%) |

| SOF/LED | 85 | – | – | 50 |

| SOF/VEL | 9 | 26 | 22 | – |

| SOF/DAC | 3 | – | 78 | – |

| SOF/RIB | – | 74 | – | – |

| ELB/GRA | – | – | – | 50 |

| OMB/PAR/DAS | 3 | – | – | – |

DAA, direct- acting antiviral agent; DAC, daclatasvir; DAS, dasabuvir; ELB, elbasvir; GRA, grazoprevir; LED, ledispavir; OMB, ombitasvir; PAR, paritaprevir; RIB, ribavirin; SOF, sofosbuvir; VEL, velapatasvir.

SVR rates according to genotype and fibrosis stage are described in table 4. As expected, SVR rates were significantly lower in genotype 3 patients and those with cirrhosis.

Table 4.

Sustained virological response (SVR) rate according to genotype and fibrosis stage in primary care treated patients

| Fibrosis stage | SVR (%) |

| ≤F3, n=133 | 96 |

| >F3, n=26 | 92 |

| Genotype | |

| 1, n=99 | 98 |

| 2, n=5 | 100 |

| 3, n=55 | 93 |

APRI for the diagnosis of advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis compared with TE

We examined the utility of APRI for ruling out cirrhosis as determined by TE in the primary care setting. We used the recommended cut-off of APRI <1 for the exclusion of cirrhosis and a TE liver stiffness of >12.5 kPa to diagnose cirrhosis.

APRI<1 had an Sn of 60.6%, Sp 83.6%, PPV 33.9% and NPV 94%, positive likelihood ratio 3.7, negative likelihood ratio 0.47 and overall accuracy of 80.8% for the exclusion of cirrhosis. We also examined the utility of APRI (cut-off of ≥2) to diagnose cirrhosis. APRI≥2 showed an Sp of 95.4%, Sn of 36%, PPV 52% and NPV 91%, positive likelihood ratio 7.87 and negative likelihood ratio 0.67 with an overall accuracy of 88%. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for APRI to diagnose cirrhosis was 0.780 (0.683–0.878).

APRI with a cut-off of <1 would allow 199 patients to avoid TE prior to commencing treatment. However, in our cohort 13 patients with possible cirrhosis as defined by TE would be misclassified by this cut-off. Using APRI (cut-off of ≥2) would allow 227 patients without cirrhosis to avoid TE, however 21 out of 32 patients with cirrhosis according to TE would be misclassified by this cut-off.

Discussion

In this real-world cohort of patients undergoing DAA treatment, we have shown that treatment in primary care is feasible and enabled by rapid access to TE. This results in excellent SVR rates and reliably identifies patients with advanced fibrosis who require follow-up in secondary care.

Furthermore, we have validated APRI (cut-off of <1) to identify patients with a very low risk of cirrhosis. Application of this cut-off would enable significant numbers of patients to access DAA treatment without the need for TE, thus streamlining access to treatment especially in the primary care setting.

Prescribing DAA in primary care is essential to increase treatment capacity and scale up treatment numbers in order to achieve HCV elimination. The HP model facilitates this by easing access to TE.

HCV treatment in primary care has been shown to be effective in the pre-DAA era and there are substantial advantages to patients in terms of treatment occurring nearer to the patient’s home and being supervised by a practitioner who is familiar to them.15 Our data confirm that treatment in primary care is associated with excellent SVR rates. The rate of incomplete SVR data was low, however was significantly higher in the primary care. Rates of loss to follow-up and therefore incomplete SVR data have previously been shown to be higher in this group.16 This is likely due to the higher prevalence of active injecting drug use, younger age and lower prevalence of advanced liver disease in primary care cohorts.17 Strategies such as early follow-up between end of treatment and SVR in addition to incentives are being explored.18

Similar to experience elsewhere in Australia, we have shown that in the first 3 months following universal availability of DAA, there was a marked increase in DAA prescriptions which then appeared to tail off.19 This is consistent with the notion of ‘warehousing’ where patients had already been assessed for treatment and were waiting for DAA therapy to become available.17 We were able to show an increase in prescribing in the most recent months, the majority of which were in primary care. This effect is likely due to new patients identified and treated through the HP programme and is compatible with our goal of broadening access to DAA therapy.19

Assessment of fibrosis to exclude cirrhosis is recommended in national guidelines prior to commencing DAA.14 This is important for two reasons, first treatment regimens and durations will differ and second patients with cirrhosis should undergo surveillance for HCC and gastro-oesophageal varices. Currently, TE is recommended for fibrosis assessment; however, TE is not widely available outside metropolitan area. The HP model of care can help address this limitation. This model is transferable and can also be applied in non-traditional healthcare settings such as prisons and needle-exchange programmes where HCV prevalence is high, supporting the concept of microelimination especially as provision of treatment in non-traditional settings has been shown to increase treatment uptake.20 21

The vast majority of patients living with HCV in Australia do not have advanced fibrosis and therefore the need for TE could be considered a barrier to providing treatment in primary care. NIT could provide an alternative method of fibrosis assessment. In Australian guidelines, APRI is recommended as an alternative to TE prior to treatment. The performance of APRI compared with TE has been evaluated previously.22 23 Doyle et al showed that APRI<1 had an NPV of 96% in a cohort of HCV-infected patients taking part in DAA trials and showed that lowering the APRI cut-off to 0.5 improved the NPV of APRI to 98%. Similarly, Kelly et al analysed the performance of NIT in a mixed population of prisoners and hospital-treated patients. They found that APRI with a cut-off of <1 had an NPV of 94% and went on to validate a lower cut-off of APRI (0.49) that had an NPV of 99% which allowed 40% of patients to avoid TE. Lowering the threshold of APRI improves the NPV for cirrhosis; however, this occurs at the expense of generating larger number of patients requiring further assessment. To our knowledge, our study is the first to examine the utility of APRI in patients treated in primary care. We found that APRI<1 to have excellent performance and using this cut-off would allow 67% of patients to avoid TE thus streamlining assessment and access to treatment.

The retrospective design of the study did not allow us to assess patient and GP acceptability of DAA prescribing in primary care; however, other studies have shown that patient experience is enhanced by being treated locally by a familiar physician.20

In summary, we show that DAA prescribing in primary care results in excellent SVR rates, equivalent to those obtained in secondary care. The hepatology partnership model appears to be highly effective at providing treatment advice to primary care physicians while simultaneously identifying patients with cirrhosis who require ongoing assessment. This model is easily adaptable to diverse treatment settings and could help increase access to treatment in marginalised or remote populations thus contributing to the elimination of HCV from Australia.

Significant of this study.

What is already known on this topic

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment has become simple in the era of pan-genotypic all-oral regimens.

HCV elimination has become realistic goal but many individuals living with HCV may not be engaged in secondary care and therefore treatment models based on secondary care may disadvantage marginalised and hard-to-reach groups of patients.

Basing treatment in primary care may increase access to treatment for patients who are not able to or who are unwilling to engage in secondary care.

What this study adds

We have shown that the use of community-based Fibroscan clinics enables HCV treatment in primary care with equivalent results to those patients treated in secondary care.

We also show that simple serum-based non-invasive tests can avoid the need for Fibroscan in many patients further simplifying treatment algorithms.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future

In order to realise the goal of HCV elimination, it is necessary to scale up and simplify treatment.

Facilitating treatment in primary care and other non-traditional settings increases the treatment ‘workforce’ and increases access to marginalised and disadvantaged groups, factors that will be crucial in achieving HCV elimination.

Footnotes

Contributors: JM and JO’B conceived and planned the study. CO, BK, SH, SK, AS, JB and NW performed the study and collected data. LW, AA, LB and JO’B drafted the manuscript. JB provided important intellectual content. JO’B and JM are guarantors of the article.

Funding: Australian Centre for Health Service Innovation (AusHSI)—Integrated care innovation fund.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane, Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/17/QPCH/365).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Further data including all biochemistry and clinical data are available. We are happy to share the de-identified data after appropriate ethics submission.

References

- 1. Gower E, Estes C, Blach S, et al. Global epidemiology and genotype distribution of the hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 2014;61:S45–S57. 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gane E, Kershenobich D, Seguin-Devaux C, et al. Strategies to manage hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection disease burden - volume 2. J Viral Hepat 2015;22:46–73. 10.1111/jvh.12352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Razavi H, Waked I, Sarrazin C, et al. The present and future disease burden of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection with today’s treatment paradigm. J Viral Hepat 2014;21:34–59. 10.1111/jvh.12248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Iversen J, Grebely J, Catlett B, et al. Estimating the cascade of hepatitis C testing, care and treatment among people who inject drugs in Australia. Int J Drug Policy 2017;47:77–85. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McGowan CE, Fried MW. Barriers to hepatitis C treatment. Liver Int 2012;32:151–6. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02706.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization. Global health sector strategy on viral hepatitis 2016-2021. Towards ending viral hepatitis 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Astell-Burt T, Flowerdew R, Boyle P, et al. Is travel-time to a specialist centre a risk factor for non-referral, non-attendance and loss to follow-up among patients with hepatitis C (HCV) infection? Soc Sci Med 2012;75:240–7. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cunningham EB, Hajarizadeh B, Bretana NA, et al. Ongoing incident hepatitis C virus infection among people with a history of injecting drug use in an Australian prison setting, 2005-2014: The HITS-p study. J Viral Hepat 2017;24:733–41. 10.1111/jvh.12701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fisher K, Smith T, Nairn K, et al. Rural people who inject drugs: A cross-sectional survey addressing the dimensions of access to secondary needle and syringe program outlets. Aust J Rural Health 2017;25:94–101. 10.1111/ajr.12304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Graham S, Maher L, Wand H, et al. Trends in hepatitis C antibody prevalence among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people attending Australian Needle and Syringe Programs, 1996-2015. Int J Drug Policy 2017;47:69–76. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cheng W, Nazareth S, Flexman JP. Statewide hepatitis C model of care for rural and remote regions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;30:1–5. 10.1111/jgh.12863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scott N, Doyle JS, Wilson DP, et al. Reaching hepatitis C virus elimination targets requires health system interventions to enhance the care cascade. Int J Drug Policy 2017;47:107–16. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lim SG. HCV management in resource-constrained countries. Hepatol Int 2017;11:245–54. 10.1007/s12072-017-9787-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thompson AJ. Australian recommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection: a consensus statement. Med J Aust 2016;204:268–72. 10.5694/mja16.00106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baker D, Alavi M, Erratt A, et al. Delivery of treatment for hepatitis C virus infection in the primary care setting. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;26:1003–9. 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wade AJ, McCormack A, Roder C, et al. Aiming for elimination: Outcomes of a consultation pathway supporting regional general practitioners to prescribe direct-acting antiviral therapy for hepatitis C. J Viral Hepat 2018;25:1089–98. 10.1111/jvh.12910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Haridy J, Wigg A, Muller K, et al. Real-world outcomes of unrestricted direct-acting antiviral treatment for hepatitis C in Australia: The South Australian statewide experience. J Viral Hepat 2018;70:1151 10.1111/jvh.12943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Morris L, Smirnov A, Kvassay A, et al. Initial outcomes of integrated community-based hepatitis C treatment for people who inject drugs: Findings from the Queensland Injectors' Health Network. Int J Drug Policy 2017;47:216–20. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hajarizadeh B, Grebely J, Matthews GV, et al. Uptake of direct-acting antiviral treatment for chronic hepatitis C in Australia. J Viral Hepat 2018;25:640–8. 10.1111/jvh.12852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bajis S, Dore GJ, Hajarizadeh B, et al. Interventions to enhance testing, linkage to care and treatment uptake for hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs: A systematic review. Int J Drug Policy 2017;47:34–46. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lazarus JV, Wiktor S, Colombo M, et al. Micro-elimination - A path to global elimination of hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2017;67:665–6. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Doyle J, Harney B, Brainard D, et al. Evaluation of APRI index to identify cirrhosis prior to direct-acting antiviral HCV treatment. J Hepatol 2018;68:S313–S314. 10.1016/S0168-8278(18)30845-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kelly ML, Riordan SM, Bopage R, et al. Capacity of non-invasive hepatic fibrosis algorithms to replace transient elastography to exclude cirrhosis in people with hepatitis C virus infection: A multi-centre observational study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0192763 10.1371/journal.pone.0192763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]